Achieving FAIR Compliance for Viral Sequence Data: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles for viral sequence data.

Achieving FAIR Compliance for Viral Sequence Data: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on implementing FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles for viral sequence data. It covers the foundational importance of FAIR data in accelerating virology research and outbreak response, explores methodological frameworks for data FAIRification, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents validation strategies through comparative analysis of existing virus databases and regulatory standards. By synthesizing current best practices and future directions, this resource aims to enhance data-driven discovery in viral genomics, therapeutic development, and public health surveillance.

The Critical Role of FAIR Principles in Modern Virology and Pandemic Preparedness

What are the FAIR Principles?

The FAIR principles are a set of guiding rules designed to improve the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability of digital assets, with particular emphasis on scientific data management and stewardship [1] [2]. Formally published in 2016, these principles were created by a diverse coalition of stakeholders representing academia, industry, funding agencies, and scholarly publishers [2] [3]. A key differentiator of FAIR is its specific emphasis on enhancing machine-actionability—the capacity of computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with minimal human intervention [1] [2]. This addresses the critical challenge of managing data given its increasing volume, complexity, and speed of creation [1].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is FAIR data the same as Open data? A: No. FAIR data is focused on making data structured, richly described, and machine-actionable, but not necessarily publicly available. It can be restricted with proper authentication and authorization. Open data is made freely available to anyone without restrictions but may lack the rich metadata and structure required for computational use [3].

Q: What are the primary benefits of implementing FAIR principles for viral research? A: Implementing FAIR principles enables faster time-to-insight by making data easily discoverable, improves data ROI, supports AI and multi-modal analytics, ensures reproducibility and traceability, and enables better collaboration across organizational silos [3]. One study in a health research context concluded that using a FAIR-based solution could save 56.57% of time and significant costs in research execution [4].

Q: We have legacy viral sequence data. Is it feasible to make this FAIR? A: Yes, but it often presents a common challenge due to the high cost and time investment required for transformation. Legacy data may be in fragmented systems and non-standardized formats, requiring retrofitting to meet FAIR standards [3]. A systematic FAIRification workflow can be applied to convert existing data into FAIR-compliant formats [4].

Q: What is a common real-world example of FAIR implementation for pathogen data? A: The GISAID initiative employs FAIR principles by assigning each viral sequence record a unique and persistent identifier (EPI_ISL ID), making data retrievable via standardized protocols, using broadly accepted data formats (FASTA, FASTQ), and maintaining detailed provenance for reusability [5].

Quantitative Impact of FAIR Implementation

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings related to the benefits and costs of FAIR data implementation from recent research:

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of FAIR Principles Implementation

| Metric | Findings | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Time Savings | 56.57% time saved in data management tasks | Health research management using FAIR4Health solution [4] |

| Economic Cost of NOT having FAIR data | €10.2 billion per year (estimated minimum) | European Union economy [4] [6] |

| Potential Additional Innovation Loss | €16 billion per year (estimated) | European Union, due to lack of FAIR data [6] |

| Recommended Investment | 5% of overall research costs should go towards data stewardship | Recommendation from expert analysis [4] |

Experimental Protocol: The FAIRification Workflow

Applying FAIR principles to existing data, a process known as "FAIRification," follows a structured pathway. The workflow below, adapted from the FAIR4Health project, details the methodology for converting health research data, such as viral sequence information, into FAIR-compliant data [4].

Diagram 1: FAIRification workflow for health data.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Data Curation and Transformation: Use a Data Curation Tool (DCT) to extract, transform, and load raw healthcare and health research data into a standardized, interoperable format. The FAIR4Health project, for instance, used HL7 FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) repositories for this purpose [4].

- Privacy Preservation: Process the standardized data through a Data Privacy Tool (DPT) to handle privacy challenges inherent in sensitive health data. This involves applying anonymization and de-identification techniques to comply with ethical and legal requirements while preserving data utility [4].

- Metadata Annotation and Identifier Assignment: Enrich the data with rich, machine-readable metadata. This critical step includes assigning a globally unique and persistent identifier (e.g., a DOI or an accession number like GISAID's EPI_ISL ID) to each dataset [5] [4]. The metadata should use formal, accessible, and broadly applicable languages and vocabularies [1].

- Repository Deposit and Indexing: Register or index the (meta)data in a searchable resource. This could be a general-purpose repository (e.g., Zenodo, FigShare) or a special-purpose repository for viral data (e.g., GISAID, GenBank) to ensure maximum findability [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Common FAIR Implementation Challenges

The following table addresses specific issues researchers might encounter when working towards FAIR compliance for viral sequence data, along with potential solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for FAIR Implementation

| Challenge | Specific Issue | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Findability | Data and metadata are scattered across platforms and file formats, making them hard to locate [6]. | Solution: Implement a centralized data indexing system. Assign globally unique and persistent identifiers (e.g., DOIs, EPI_ISL IDs) to each dataset and its metadata. Register datasets with global registries like re3data.org [1] [5]. |

| Accessibility | Data access is restricted due to privacy, proprietary concerns, or unclear authentication protocols [6]. | Solution: Use standardized, open communications protocols (like HTTPS). Implement clear authentication and authorization procedures where necessary, and ensure metadata remains accessible even if the data itself is no longer available [1] [5]. |

| Interoperability | Incompatible software systems, tools, and a lack of standardized data models or ontologies impede data integration [6]. | Solution: Use formal, accessible, and shared languages for knowledge representation. Store and exchange data in broadly accepted, machine-readable formats (e.g., CSV, JSON, FASTA, FASTQ). Use community-standardized vocabularies and ontologies for metadata fields [5] [7]. |

| Reusability | Inadequate documentation, incomplete metadata, and unclear licensing affect data quality and reliability, hindering reuse [6]. | Solution: Ensure (meta)data are richly described with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes. Maintain clear provenance information and state data usage licenses clearly. Adhere to relevant community standards developed with domain experts [1] [5]. |

| Cultural & Resource | Lack of recognition for data sharing, limited incentives, and insufficient infrastructure or technical expertise [6]. | Solution: Advocate for institutional policies that recognize and reward data sharing. Invest in training and secure resources for data stewardship, which is recommended to be ~5% of overall research costs [4] [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials, tools, and infrastructure components essential for conducting research and ensuring FAIR compliance of viral sequence data.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for FAIR Viral Sequence Data Management

| Item / Solution | Function in FAIR Compliance |

|---|---|

| Trusted Data Repository (e.g., GISAID, GenBank, Zenodo) | Provides a sustainable infrastructure for depositing, preserving, and providing access to data. Ensures persistent identifiers and indexing, fulfilling Findability and Accessibility principles [5] [2]. |

| Standardized Ontologies & Vocabularies (e.g., SNOMED CT, MeSH) | Provides a formal, accessible, shared language for knowledge representation. Enables semantic interoperability by ensuring metadata uses consistent, FAIR-compliant vocabularies, fulfilling the Interoperability principle [7] [3]. |

| Data Curation Tool (DCT) | Facilitates the extraction, transformation, and loading of raw data into standardized, interoperable formats (e.g., HL7 FHIR). A core component of the FAIRification workflow [4]. |

| Data Privacy Tool (DPT) | Handles the anonymization and de-identification of sensitive health data, allowing for Accessibility and Reusability while complying with ethical and legal requirements [4]. |

| Persistent Identifier Service (e.g., DOI, EPI_ISL ID) | Mints globally unique and persistent identifiers for datasets. This is a foundational requirement for data Findability, Accessibility, and citation [1] [5]. |

| Machine-Readable Metadata Schema | A structured template for capturing rich, machine-actionable metadata. This is critical for making data Findable by computers and Reusable by others by providing essential context [1] [2]. |

In the fields of viral genomics and outbreak response, the vast and growing volume of sequence data presents both an unprecedented opportunity and a significant challenge. The FAIR Guiding Principles—making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—provide a critical framework for managing this deluge of information [3]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, FAIR compliance transforms raw viral sequences into a powerful, collaborative resource that can accelerate scientific discovery and strengthen public health responses to emerging threats [5] [8].

Adhering to FAIR principles ensures that data from arduous field collection and meticulous laboratory work can be fully leveraged by the global community, enabling rapid development of countermeasures, as evidenced during the COVID-19 pandemic [9]. This technical support center is designed to help you navigate the practical implementation of these principles, troubleshoot common issues, and integrate best practices into your research workflow.

Troubleshooting FAIR Compliance: A Guide for Researchers

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Table: Common FAIR Compliance Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge Category | Specific Issue | Proposed Solution | Key References/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Findability | How to ensure my dataset is discoverable after submission? | Insist on repositories that assign globally unique, persistent identifiers (e.g., EPI_ISL ID in GISAID, DOI) and index data with rich, machine-readable metadata [5]. | GISAID, GenBank, DOI Services |

| Data Accessibility | How to share data responsibly before my own publication? | Utilize a "Data Reuse Information (DRI) Tag" linked to your ORCID to signal a request for collaboration prior to reuse, balancing openness with contributor recognition [9]. | ORCID, DRI Tag Framework [9] |

| Data Interoperability | My metadata is not understood by other labs or platforms. | Use controlled, documented vocabularies and community-agreed standards for metadata fields (e.g., host, location, sequencing method). Store data in broadly accepted, machine-readable formats (CSV, TSV, FASTA, FASTQ) [5] [3]. | Public Health Ontologies, CSV/TSV, FASTA/FASTQ |

| Data Reusability | How to guarantee my data can be replicated and reused? | Provide detailed provenance: include origin, submission info, and laboratory methods. Release data under a clear usage license and adhere to community-defined data quality standards [5] [10]. | GISAID Access Agreement, Creative Commons Licenses |

| Ethical Reuse | How to avoid "helicopter research" and ensure fairness to data contributors? | Actively involve originating researchers in new projects, especially when data lacks a formal publication. Adhere to a "code of honour" for reuse that recognizes data generators [9]. | Roadmap for Equitable Reuse [9] |

Experimental Protocols for FAIR Viral Data Submission

Protocol 1: Submitting Viral Sequence Data to a FAIR-Compliant Repository

This protocol outlines the steps for preparing and submitting viral genome sequence data to a repository like GISAID, which exemplifies FAIR principles [5].

- Select a Repository: Choose a recognized, FAIR-aligned repository such as GISAID or GenBank. The choice may be dictated by funder requirements, journal policies, or pathogen-specific community standards.

- Prepare Sequence Data:

- Format: Assemble the consensus genome and save it in a standard format (e.g., FASTA).

- Quality Control: Verify sequence quality, length, and the absence of contamination.

- Compile Rich Metadata: This is critical for interoperability and reuse. Essential metadata includes [5] [10]:

- Unique Identifier: The repository will often assign this (e.g., EPI_ISL ID).

- Temporal & Geographic: Date and location of specimen collection.

- Host Information: Species, age, sex (where applicable and respecting confidentiality).

- Clinical Context: Disease severity, symptoms, comorbidity, travel history.

- Methodological Data: Sequencing technology, assembly protocol, and bioinformatics tools used.

- Submit Data:

- Follow the repository's submission workflow via its web interface or API.

- Adhere to the specific data-sharing agreement, which governs accessibility and reuse terms [5].

- Obtain Persistent Identifier: Upon acceptance, the repository will mint a persistent identifier (e.g., EPI_ISL ID or DOI). Cite this identifier in any related publications to ensure findability and fulfill acknowledgment requirements [5].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Data Reuse Information (DRI) Tag

For data being prepared for public release, this protocol, based on a 2025 roadmap, helps ensure equitable reuse [9].

- Create an ORCID: Ensure all contributing researchers have a unique, persistent digital identifier (ORCID).

- Link ORCID to Dataset: During submission to a repository, associate the dataset with the ORCIDs of the data collectors.

- Define Reuse Expectations: This linkage acts as the DRI Tag, signaling to the community that the data generators should be contacted and considered for collaboration before the data is reused in new projects.

- Communicate Freely Reusable Status: If the data is intended for immediate and unrestricted reuse, the dataset can be submitted without a linked DRI Tag, making this status clear to potential users [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Tools for FAIR-Compliant Viral Genomics

| Item/Tool | Function in FAIR Viral Research |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencer (e.g., Illumina, Oxford Nanopore) | Generates the primary raw genomic data; portable platforms enable real-time, in-field sequencing during outbreaks [11]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines (e.g., detectEVE, Serratus) | Processes raw sequence data, performs quality control, assembly, and annotation; open-source tools ensure methodological interoperability and reproducibility [11] [12]. |

| FAIR-Compliant Repositories (e.g., GISAID, NCBI GenBank) | Provides the infrastructure for storing, sharing, and accessing data with persistent identifiers, access controls, and standardized metadata, fulfilling the core FAIR requirements [5] [3]. |

| Controlled Vocabularies & Ontologies (e.g., Public Health Ontologies) | Provides standardized language for metadata fields, ensuring that data from different sources is interoperable and machine-readable [5] [3]. |

| ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID) | A persistent digital identifier for researchers, crucial for unambiguous attribution of data and for implementing the DRI Tag for equitable reuse [9]. |

| AI/ML Tools for Viral Discovery | Machine learning models and platforms (e.g., Serratus) can scan petabase-scale public sequence data to identify novel viruses, predict host ranges, and classify unknown sequences, relying entirely on the availability of FAIR data for training and operation [8] [11]. |

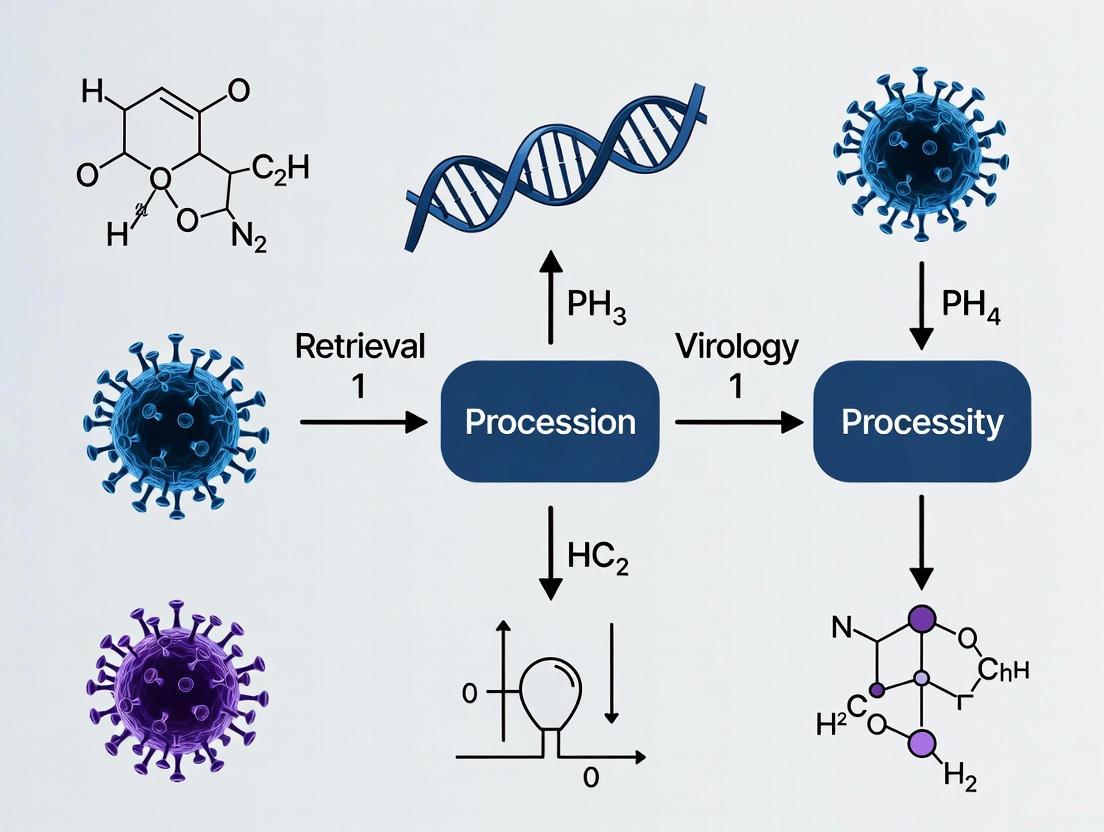

Visualizing the FAIR Data Workflow for Viral Genomics

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and interactions between key entities in a FAIR-compliant viral data management system.

FAIR-Compliant Viral Data Lifecycle

Implementing FAIR principles is not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental requirement for maximizing the value of viral sequence data in public health and research. By making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, the global scientific community can build a resilient and collaborative ecosystem. This enables faster responses to outbreaks, accelerates drug and vaccine discovery, and ensures that the critical contributions of data generators are recognized and respected. The tools and guidelines provided here offer a practical path toward achieving these essential goals.

Viral sequence databases are critical infrastructures for modern infectious disease research, outbreak response, and drug development. The FAIR principles—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—provide a framework for evaluating and improving these resources [3]. These principles emphasize machine-actionability, ensuring data is structured not just for human access but for computational systems to process with minimal human intervention [3]. This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when working with these databases and provides protocols to ensure their work aligns with FAIR compliance requirements.

The table below summarizes key virus databases and their alignment with FAIR principles.

Table 1: Virus Database Landscape and FAIR Principles Compliance

| Database Name | Primary Content & Coverage | Findability Features | Accessibility Policy | Interoperability Standards | Reusability Provisions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GISAID | Genetic sequence data from high-impact pathogens (e.g., influenza, SARS-CoV-2) [5] | Unique, persistent EPIISL ID for each sequence; EPISET ID with DOI for collections; indexed in global registries [5] | Free registration with user authentication; data retrievable via HTTPS protocol; metadata remain accessible even if data is withdrawn [5] | Uses standardized formats (CSV, TSV, JSON, FASTA, FASTQ); controlled vocabulary; cross-referencing with publications [5] | Clear access agreement; detailed provenance; data curated to community standards; versioning for updates [5] |

| PalmDB | Database of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) sequences from over 100,000 RNA viruses [13] | Serves as a reference for tools like kallisto to identify viral species in transcriptomic data. | Integrated into open-source software tools (kallisto); enables detection of unexpected or novel viruses in RNA sequence data [13]. | Used with kallisto software for quantifying viral presence in host samples like human lung tissue [13]. | Facilitates the study of viral impact on biological functions and monitoring of emerging diseases [13]. |

| GenBank (NIH) | Annotated collection of all publicly available DNA sequences (Open Data) [3] | Open access: freely available for anyone to access without restrictions [3]. | While open, data is not necessarily FAIR unless properly curated with metadata [3]. |

Troubleshooting Common Database Issues

FAQ 1: My submission to a database was used by another group before I could publish my own analysis. How can I protect my rights?

- Issue: Data generators risk being "scooped" when data is shared rapidly and reused without appropriate attribution or collaboration [9].

- Solution: A new framework proposes the use of a Data Reuse Information (DRI) Tag linked to a researcher's ORCID identifier [9]. When submitting data:

- Provide your ORCID: This unambiguously attributes the dataset to you and signals to potential users that they should contact you before reuse.

- Check for DRI Tags: When reusing data, always check for the presence of a DRI Tag and respect the contributor's guidelines. If the identifier is absent, the data can be considered freely reusable [9].

- FAIR Context: This practice balances the "A" (Accessible) and "R" (Reusable) principles by ensuring accessibility while protecting the authority and rights of data contributors, aligning with ethical data stewardship.

FAQ 2: I found a sequence in a database, but it lacks critical metadata like host information or collection date. How should I proceed?

- Issue: Incomplete metadata severely limits the data's utility for analyses such as transmission dynamics or host tropism.

- Solution:

- Contact the Submitter: Use the contact information provided in the database record, if available.

- Check Linked Publications: Use the database's cross-referencing功能 to find scientific publications that may have used the sequence and contain more context [5].

- Acknowledge the Gap: In your own research, explicitly document this lack of metadata as a limitation.

- FAIR Context: This issue highlights a gap in "F" (Findable) and "R" (Reusable) principles, which require data to be described with rich metadata (R1) to enable reuse [5]. The decision on which metadata to share often remains with the submitter and can be limited by patient confidentiality or resource availability [5].

FAQ 3: I need to integrate genomic sequence data with clinical metadata from a different source. Why is this so difficult?

- Issue: A lack of standardized vocabularies and ontologies across data sources creates interoperability barriers [3].

- Solution:

- Use Controlled Vocabularies: Advocate for and use community-agreed terms for metadata (e.g., for host species, geographic location).

- Leverage Persistent Identifiers: Some databases allow cross-referencing with external clinical datasets using persistent identifiers [5].

- Utilize Interoperable Formats: Work with data exported in standardized, machine-readable formats like CSV, TSV, or JSON [5].

- FAIR Context: This directly addresses the "I" (Interoperable) principle, which requires data to use formal, accessible, and broadly applicable languages for knowledge representation [5] [3].

Experimental Protocol: Submitting Viral Sequence Data to a FAIR-Compliant Repository

This protocol ensures your viral sequence data is submitted in a manner that maximizes its Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability for the global research community.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Sequencing and Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Viral Research |

|---|---|

| Sample Collection Kit (e.g., nasopharyngeal swab, viral transport media) | Collects and preserves viral material from the host for transport to the laboratory. |

| RNA/DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates and purifies viral genetic material from the patient sample. |

| Reverse Transcription & Amplification Reagents | Converts viral RNA into DNA and amplifies specific genomic regions for sequencing (e.g., via PCR). |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | Determines the nucleotide sequence of the amplified viral genome at high throughput. |

| Bioinformatics Tools (e.g., BLAST, Clustal Omega, DeepVariant) | For analyzing sequence data, including assembly, alignment, variant calling, and phylogenetic analysis [14]. |

Procedure:

Pre-Submission: Data and Metadata Collection

- Generate Sequence Data: Use your preferred NGS platform to generate the viral genome sequence. Assemble the raw reads into a consensus sequence.

- Compile Rich Metadata: This is critical for reusability. Collect all relevant information using the database's required controlled vocabulary [5]. Essential metadata includes:

- Virus: Virus name, target gene.

- Host: Host species, health status, anonymity of patient.

- Sample: Sample source (e.g., nasopharyngeal swab), collection date, geographic location.

- Sequencing: Sequencing instrument, assembly method.

- Originating Lab: Lab name, address, responsible scientist.

- Submitting Lab: Lab name, address, submitter name.

Submission: Data Upload and Validation

- Select a FAIR-Compliant Database: Choose an appropriate repository like GISAID for high-impact pathogens [5].

- Register for an Account: Complete the free registration, agreeing to the database's terms of use and access agreement [5].

- Upload Data and Metadata: Use the platform's web interface or API to submit the sequence (in FASTA format) and the associated metadata.

- Validate Your Submission: The database's curation team will perform quality checks on your submission. You may be contacted for clarification or corrections.

Post-Submission: Obtaining Identifier and Citing Data

- Receive Accession Number: Upon successful curation, your data will be assigned a globally unique and persistent identifier (e.g., an EPI_ISL ID in GISAID) [5]. This is the core of Findability.

- Cite the Data in Publications: When publishing, use this accession number in your "Data Availability Statement" to ensure transparency and reproducibility. For a collection of sequences, you may receive an EPI_SET ID with a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) for easier citation [5].

The following diagram outlines the submission and reuse workflow, highlighting key FAIR principles at each stage.

Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

Despite advances, significant knowledge gaps persist in the landscape of virus databases:

- Equity in Data Sharing: There is a tension between rapid, open data sharing and fairly recognizing the contribution of data generators [9]. The implementation of mechanisms like the DRI Tag is a new development aimed at closing this gap and requires broad community adoption to be effective.

- Metadata Completeness: The variability in the quality and completeness of submitted metadata remains a major hurdle for robust meta-analysis and limits the full reusability of datasets [5].

- Bias in Database Coverage: Genomic databases can be biased towards viruses from certain geographic regions or from hosts of particular economic or medical interest. Initiatives like H3Africa are working to build capacity for genomics research in underrepresented populations and are crucial for creating a truly global atlas of viral diversity [15].

- Integration of FAIR and CARE Principles: While FAIR focuses on data quality and utility, the CARE principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics) are essential for the ethical handling of data involving Indigenous peoples and other marginalized communities [3]. Future frameworks must integrate both to be both technologically sound and ethically responsible.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

SRA Submission Portal: Common Errors and Solutions

This guide addresses frequent errors encountered during data submission to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA).

| Error / Warning Message | Problem Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Error: Multiple BioSamples cannot have identical attributes [16] | Samples are not distinguishable by at least one controlled attribute; "sample name" or "description" are not considered [16]. | Add distinguishing columns to the attribute sheet (e.g., replicate, salinity, collection time). For biological replicates, add a replicate column [16]. |

| Error: These samples have the same Sample Names and identical attributes [16] | The submission is attempting to create samples that duplicate ones already registered in your account [16]. | On the 'General Info' tab, select Yes for "Did you already register BioSamples?" and use existing sample accessions in your SRA metadata [16]. |

| Warning: You uploaded one or more extra files [16] | Files are present in the upload folder that are not listed in the SRA Metadata table [16]. | Either remove the extra files or update your SRA_metadata spreadsheet to include them. Only files listed in the metadata will be processed [16]. |

| Error: Some files are missing. Upload missing files or fix metadata table. [16] | Files listed in the SRA Metadata table were not found in the submission folder [16]. | Upload the missing files. Check that filenames in your metadata, including extensions, exactly match the uploaded files [16]. |

Error: File <filename> is corrupted [16] |

The file is corrupt, either on your side or due to transfer issues [16]. | Check file integrity (e.g., for gzipped files, use zcat <filename> | tail). Re-upload an uncorrupted version of the file [16]. |

| I uploaded all data files but cannot see any folders when prompted [17] | Files were uploaded directly into the root of the account folder instead of a dedicated subfolder [17]. | Create a subfolder within your account folder and move your files into it. Wait about 15 minutes for file discovery before selecting it [17]. |

Bioinformatic Virus Identification: Tool Selection and Validation

This guide helps troubleshoot issues related to selecting and using bioinformatic tools for identifying viral sequences in metagenomic data.

| Problem Area | Key Challenge | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Tool Selection [18] | Performance of virus identification tools is highly variable, with true positive rates from 0–97% and false positive rates from 0–30% [18]. | On real-world data, tools like PPR-Meta, DeepVirFinder, VirSorter2, and VIBRANT show better performance distinguishing viral from microbial contigs [18]. |

| Parameter Adjustment [18] | Using default tool cutoffs may not be optimal for a specific dataset or biome [18]. | Adjust parameter cutoffs before use. Benchmarking indicates that performance improves significantly with adjusted cutoffs [18]. |

| Tool Complementarity [18] | Different tools often identify different subsets of viral sequences [18]. | Employ a multi-tool approach, as most tools find unique viral contigs. This increases the sensitivity of virus detection [18]. |

| Host Association [19] | Incorrectly associating a viral sequence with the sampled species (e.g., the host's diet) rather than the true host [19]. | Perform phylogenetic analysis to validate novel sequences and infer likely hosts. Do not rely solely on the sample source for host assignment [19]. |

| Lack of Phylogenetics [19] | Reporting viruses using only similarity searches (BLAST) or diversity metrics without phylogenetic validation [19]. | Conduct and report phylogenetic analyses. This is central to virus classification and provides a basis for evolutionary and ecological inferences [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Submission and Data Management

Q1: I've registered my BioProject and BioSamples elsewhere. How do I avoid creating duplicates when submitting to SRA? [16] [20] On the "General Info" step of the SRA Submission Wizard, you must select Yes in response to "Did you already register BioSamples for this data set?" This will skip the BioSample creation steps and allow you to use your existing accessions in the SRA metadata [16] [20].

Q2: How do I structure my SRA metadata for multiple experiments or technical replicates? [17]

- Each row in the SRA metadata template represents one Experiment (a unique combination of sample, library, strategy, layout, and instrument model) [17].

- To create multiple experiments (e.g., libraries/replicates) for the same sample, use the same

sample_nameorsample_accessionin multiple rows [17]. - Only one Run is allowed per Experiment. For technical replicates (multiple sequencing runs of the same library), list all file names consecutively in the same row [17].

Q3: What is the recommended way to download SRA data for analysis? [21]

The supported method is to use the prefetch tool from the SRA Toolkit. Avoid using generic tools like ftp or wget, as they can create incomplete files and complicate troubleshooting. prefetch ensures all file dependencies and external reference sequences are correctly downloaded [21].

Q4: My manuscript reviewer needs access to my private submission. How do I provide it? [17] In the Submission Portal's "Manage Data" interface, find your BioProject and press the "Reviewer link" button. This generates a temporary link that provides access to the metadata. Note that this link expires after the data is publicly released [17].

FAIR Principles and Data Compliance

Q5: How does proper SRA submission align with FAIR Data Principles? FAIR Principles provide guidelines to enhance the Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse of digital assets [1]. Submitting to SRA directly supports these principles:

- Findable: Your data is assigned a unique BioProject accession (

PRJNA#) and Run accessions (SRR#), making it indexable and searchable in public databases [17]. - Accessible: Data is retrieved using standardized protocols. While access may be controlled during a publishing embargo, metadata is often accessible, and clear paths to access are provided [5] [3].

- Interoperable: SRA requires data and metadata in specific, standardized formats (e.g., FASTQ, controlled vocabulary for attributes), enabling integration with other datasets and analytical workflows [16] [20].

- Reusable: Rich metadata submitted with your project provides the provenance, context, and experimental detail necessary for others to understand and reuse your data [19] [3].

Q6: What are the common pitfalls in reporting virome-scale metagenomic data that hinder its reusability? [19]

- Insufficient Metadata: Omitting key details like collection date, location, host health status, and sample type limits the ecological context [19].

- Inadequate Methodological Detail: Failing to describe viral enrichment steps, extraction kits, or bioinformatic workflows (e.g., whether all reads were assembled or only those identified as viral) affects reproducibility [19].

- Poor Sequence Characterization: Depositing sequences with no annotation, uninformative names (e.g., "unclassified Riboviria"), or without phylogenetic analysis reduces the utility of public databases [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item | Function / Application in Virus Discovery |

|---|---|

| SRA Toolkit [21] | A suite of tools, including prefetch and fasterq-dump, to reliably download and access sequencing data from the SRA for local analysis. |

| Kallisto (with translated search) [22] | A tool expanded to perform translated nucleotide-to-amino acid alignment, enabling detection of divergent RNA viruses by targeting conserved RdRP domains. |

| PalmDB [22] | A database of conserved amino acid sequences from the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) used for sensitive identification of RNA viruses beyond reference genomes. |

| VirSorter2 & VIBRANT [18] | Bioinformatic tools that use machine learning and homology searches to identify viral sequences from metagenomic assemblies. |

| BioSample & SRA Metadata Templates [16] [20] | Standardized spreadsheets provided by NCBI to ensure the consistent and complete reporting of sample attributes and sequencing experiment details. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Translated Search for RNA Virus Detection in Metagenomic Data

This methodology leverages the highly conserved RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) for sensitive virus detection [22].

- Principle: Nucleotide sequencing reads are reverse-translated in all six reading frames and aligned to an amino acid reference database (PalmDB). This method is robust to silent mutations and can detect viruses divergent from those in standard nucleotide reference databases [22].

- Workflow:

- Input: Bulk or single-cell RNA-seq data (FASTQ files).

- Code Execution: The workflow can be executed efficiently on a standard laptop [22].

- Alignment: The six reading frames of the sequencing reads are pseudoaligned to the reverse-translated PalmDB sequences. The best alignment frame is selected for each read [22].

- Output: A list of detected viral sequences with taxonomic assignments.

The following diagram illustrates the core computational process of the translated search.

Protocol: Submitting Data to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA)

A standardized protocol for ensuring your virome data is accessible and FAIR-compliant.

- Prerequisites:

- Submission Steps:

- Login & Initiate: Log in to the SRA Submission Portal and create a new submission to get a temporary

SUB#ID [20]. - General Info: Declare if a BioProject/BioSample already exists to prevent duplicates [16].

- BioSample Attributes: Provide specific and unique metadata for each biological sample. Use the NCBI Taxonomy Browser for accurate organism names [20].

- SRA Metadata: Upload a metadata spreadsheet linking your samples to the data files. Each row defines one sequencing experiment [20].

- File Upload: Pre-upload files to your personal submission folder via FTP/Aspera. Ensure filenames in the metadata match the uploaded files exactly [16] [20].

- Overview & Submit: Review all information and submit. Processing can take over 24 hours [16].

- Login & Initiate: Log in to the SRA Submission Portal and create a new submission to get a temporary

The diagram below outlines the logical sequence of the submission process and its connection to the FAIR principles.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when working with viral sequence data and implementing FAIR principles, based on documented experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our clinical data from COVID-19 patients is stored in different hospital systems with different formats. What is the first step to make it FAIR?

A1: The foundational step is to implement a FAIRification process that includes goal definition and project examination [23]. For clinical data, this typically involves:

- Define a clear FAIRification goal: For example, "To make COVID-19 patient cytokine data machine-actionable to enable federated analysis across hospitals." This goal should be specific and avoid simply stating "make data FAIR" [23].

- Conduct a data requirement analysis: Characterize all data types, identifiers, and existing metadata [23].

- Use ontological models: Transform raw, siloed data into machine-actionable digital objects by annotating them with community-developed standards and semantic models, such as those built upon the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership Common Data Model (OMOP CDM) or core ontological models for common data elements [24] [25]. This creates a virtual warehouse without needing to move data from existing systems.

Q2: We need to share SARS-CoV-2 genomic data quickly, but also ensure contributors get credit. How can FAIR principles help with this?

A2: The GISAID initiative provides a model for this. Its implementation of FAIR principles directly addresses fairness and contributor attribution [5]:

- Findability & Provenance: GISAID assigns a unique, persistent identifier (EPI_ISL ID) to each sequence record, ensuring granular traceability. It also captures rich metadata, including submitting and originating labs [5].

- Reusability: Data are released under a clear access agreement that includes provisions for temporary publishing embargoes, protecting contributors' publication rights while making data available for public health response [5]. This balances rapid sharing with academic credit.

Q3: Our research consortium struggles with semantic interoperability. Different teams use different terms for the same clinical concepts. What is the solution?

A3: This is a common barrier, often categorized as a lack of standardized metadata or ontologies [3]. The solution involves:

- Adopt Controlled Vocabularies: Use community-developed, machine-readable standards like Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) for laboratory tests and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT) for clinical terms [26].

- Implement a Common Data Model (CDM): Standards like the OMOP CDM ensure both semantic and syntactic interoperability. They allow researchers to write analyses that can be run across multiple, federated databases without sharing raw data directly [25].

- Tooling Support: Use metadata management tools like CEDAR to create templates that enforce the use of controlled vocabularies when capturing metadata [27].

Q4: What are the most critical resource and skill gaps that hinder FAIR implementation in a pandemic?

A4: Systematic identification of barriers shows that the most impactful challenges are often external and related to tooling [25]. The top recommendations to overcome them are:

- Dedicate Expertise: Add a FAIR data steward to the research team. This role possesses the expert knowledge of data, metadata, identifiers, and ontologies that is often lacking [25].

- Provide Accessible Guidance: Create and use accessible step-by-step guides and FAIRification frameworks to provide practical, actionable advice [23] [25].

- Ensure Sustainable Funding: Advocate for proper investments in the implementation and long-term maintenance of FAIR data infrastructure, which is often a high-cost activity [25] [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Data Workflow Issues

Issue: Inability to integrate genomic data with clinical and imaging data for cross-modal analysis.

- Root Cause: Fragmented data systems and formats; lack of cross-referencing capabilities [28] [3].

- Solution:

- Ensure all datasets are annotated with persistent, globally unique identifiers.

- Implement interoperability technologies like FAIR Data Points (FDPs) to expose metadata in a standardized way [24].

- Use platforms that support cross-referencing, allowing sequences to be linked to external clinical datasets via these identifiers [5].

Issue: Delays in data sharing due to complex and unclear data access procedures and governance.

- Root Cause: Data access regulations are not machine-actionable; governance structures are undefined [28] [25].

- Solution:

- Define and publish a clear Data Usage License or Agreement on the resource website [28].

- Use authentication and authorization protocols that are standardized (e.g., HTTPS) and describe the access procedure clearly in the metadata [5].

- Implement FAIR Data Points that can communicate access restrictions and conditions to machines, enabling automated assessment of data reuse possibilities [24].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section details specific methodologies cited in the case study for making COVID-19 data FAIR.

Protocol 1: FAIRification of Observational Clinical Data in a Hospital

Objective: To transform siloed, heterogeneous clinical data (e.g., lab measurements, patient observations) into machine-actionable FAIR Digital Objects (FDOs) for secondary use and federated analysis [24].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Data Acquisition & Initial Storage:

- Collect raw data from source systems (e.g., clinical laboratory information systems, Electronic Health Records - EHRs).

- Transfer data to an Electronic Data Capture (EDC) system like Castor for uniform electronic capture [24].

Data Harmonization:

- Import data from the EDC into a data warehouse system like Opal.

- Perform syntactic transformations and initial annotations using a vocabulary chosen by the user. This makes data syntactically machine-readable and provides researchers a central access point [24].

Semantic Modeling & Interoperability (Key FAIR Step):

- Model Data with Ontologies: Develop or reuse ontological models (e.g., the EJP RD core model for common data elements) to represent data records and metadata. This links the data to a formal, shared knowledge representation [24].

- Map to a Common Data Model: Transform the harmonized data into a community standard like the OMOP CDM. This requires mapping local source terminologies to standard concepts (e.g., LOINC, SNOMED-CT) to achieve semantic interoperability [25].

Metadata Exposure & Findability:

- Deploy a FAIR Data Point (FDP). The FDP is a service that exposes the metadata about the dataset (the "who, what, when, where") in a machine-readable standard [24] [27].

- The FDP metadata must include the persistent identifier of the dataset, access instructions, license information, and the ontologies used.

Access & Reuse:

- The resulting FDOs can now be discovered via the FDP and are prepared for federated querying. Analytical workflows can interact with the FDP and the data it describes to perform "data visiting" without necessarily moving large datasets [24].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Machine-Actionable Data Sharing Platform (GISAID Model)

Objective: To create a data sharing resource for pathogen genomic data that incentivizes rapid sharing by ensuring fairness, transparency, and scientific reproducibility, in alignment with FAIR principles [5].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Data Submission:

- Submitters (labs) provide genetic sequences and associated metadata using a structured, controlled vocabulary [5].

Curation and Persistent Identification:

- The platform's curation team performs quality checks.

- A globally unique and persistent identifier (EPI_ISL ID) is minted for each sequence and its metadata. This ID enables granular traceability and versioning [5].

Metadata Enrichment:

- The platform automatically annotates sequences with additional context, such as clade and lineage assignments, and nucleotide substitutions.

- Cross-referencing is implemented to link sequences to peer-reviewed studies that use them, enriching provenance [5].

Accessible and Secure Distribution:

- Data are made retrievable via standardized, open protocols (HTTPS) and a web interface.

- User authentication is required, governed by a public access agreement. This balances open access with accountability and ensures transparent use of data [5].

Reuse and Attribution:

- Data are released under a clear license with terms that protect contributors' publication rights (e.g., via temporary embargoes).

- The platform facilitates citation by providing stable identifiers (EPI_ISL ID, DOI) that can be included in data availability statements [5].

Table 1: Distribution and Characteristics of COVID-19 Data-Sharing Resources [28]

| Characteristic | Registries (44 Identified) | Platforms (20 Identified) |

|---|---|---|

| General Focus | Often comorbidity or body-system specific. | Often focus on high-dimensional data (omics, imaging). |

| Typical Data Harmonization | Use shared Case Report Forms (CRFs) for prospective harmonization. | Allow direct upload of diverse datasets; perform retrospective harmonization. |

| FAIR Implementation | Less likely to fully implement FAIR principles compared to omics/platform resources. | More likely to implement FAIR principles, especially for omics data. |

| Geographic Concentration | Concentrated in high-income countries. | Concentrated in high-income countries. |

Table 2: FAIRness Assessment of Shared COVID-19 Research Data [29]

| Assessment Metric | Finding | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sharing Prevalence | Sparse in medical research. | Based on a review of open-access COVID-19-related papers. |

| FAIR Compliance of Shared Data | Often fails to meet FAIR principles. | Shared data often lack required properties like persistent identifiers and machine-readable metadata. |

| Automated FAIR Assessment Feasibility | Challenging for context-specific principles. | Tools struggle to fully assess "Interoperability" and "Reusability," which often require subjective, community-specific evaluation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools & Platforms for FAIR Viral Research Data

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in FAIRification |

|---|---|---|

| OMOP CDM [25] | Common Data Model | Provides a standardized schema for observational health data, enabling semantic and syntactic interoperability for analytics. |

| GISAID [5] | Domain-Specific Repository | A trusted platform for sharing pathogen genomic data that implements FAIR principles to incentivize rapid, equitable, and attributable data sharing. |

| FAIR Data Point (FDP) [24] [27] | Metadata Service | A tool to expose and discover metadata about datasets and services, making them findable and defining how they can be accessed and used. |

| CEDAR [27] | Metadata Authoring Tool | Enables the creation of rich, machine-actionable metadata using templates and controlled vocabularies, which is crucial for interoperability. |

| LOINC & SNOMED-CT [26] | Controlled Vocabulary / Ontology | International standard terminologies for identifying health measurements, observations, and documents, essential for semantic interoperability. |

| VODAN-in-a-Box [27] | Implementation Package | A toolset that facilitates the creation of an internet of FAIR data, enabling "data visiting" across distributed sites, such as hospitals. |

Implementing FAIRification Frameworks: Practical Strategies for Viral Data Management

Step-by-Step FAIRification Process for Viral Genomic Data

The FAIRification process transforms existing data to be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable. For viral genomic data, this process is typically divided into three main phases [30].

Table: FAIRification Process Phases

| Phase | Key Steps | Primary Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-FAIRification | 1. Identify FAIRification Objectives2. Analyse Data3. Analyse Metadata | Define scope, assess current state, and plan the FAIRification project. |

| FAIRification | 4. Define Semantic Model5. Make Data Linkable6. Host FAIR Data | Transform data and metadata into machine-readable, interoperable formats and publish them. |

| Post-FAIRification | 7. Assess FAIR Data | Evaluate outcomes against objectives and ensure sustainability. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential and iterative nature of this workflow:

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do we initiate the FAIRification process for our SARS-CoV-2 sequencing data? Start by clearly defining your FAIRification objectives in the Pre-FAIRification phase [30]. Determine the primary use cases: is the data for global surveillance (e.g., submission to ENA/GISAID), research (e.g., variant analysis), or both? Focus initially on a critical subset of data elements, such as the consensus sequence and essential metadata (collection date, geographic location) [30] [31]. This scoping makes the initial project manageable.

Q2: What are the most common metadata standardization challenges for viral genomic data? The primary challenge is collecting rich, structured metadata necessary for interoperability and reuse [8]. Incomplete metadata (e.g., missing collection date or host information) is a major hurdle. Use public standards like the INSDC (International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration) pathogen package or GA4GH (Global Alliance for Genomics and Health) standards to define your semantic model [31] [32]. This ensures your data can be integrated with other datasets.

Q3: Our data is sensitive. How can we make it FAIR without compromising privacy or equity? Adopt the FAIR+E (Equitable) principles [31]. This involves establishing data ownership where the data is generated and building trust. Technical and governance solutions include:

- Controlled Access: Using Data Access Committees (DACs) as recommended by the GA4GH framework [32].

- Data Anonymization: Implementing techniques to remove personally identifiable information before sharing [33].

- Brokering Model: Submitting data to a trusted national or institutional data hub that can perform curation and controlled brokering to international repositories on your behalf [31].

Q4: How do we make viral sequence data machine-readable and linkable? Transform your sequence data and metadata into a linkable, machine-readable format like the Resource Description Framework (RDF) [30]. This step enables interoperability by allowing machines to automatically discover and link your data to other resources (e.g., linking a viral sequence to a specific variant in a knowledge base). This is crucial for automated analyses and AI applications [8].

Q5: How do we assess if our FAIRification was successful? In the Post-FAIRification phase, re-assess your data using the same FAIR Maturity Indicators (MI) from the initial analysis [30]. Compare the pre- and post-FAIRification scores. The ultimate test is whether the data can be used for its intended objectives, such as being successfully submitted to a designated repository like the EU Covid-19 Data Portal and integrated into analysis platforms like NextStrain [8] [31].

Common Error Scenarios and Resolutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common FAIRification Issues

| Error Scenario | Potential Cause | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Data submission to international repository fails. | Inconsistent metadata format or missing mandatory fields. | 1. Validate metadata against the repository's required schema (e.g., INSDC, ENA checklists).2. Use a metadata validation tool provided by the repository or a data brokering platform [31]. |

| Automated tools cannot process the published data. | Data is not truly machine-readable (e.g., stored in PDFs or non-standard formats). | 1. Convert data to a standard, machine-actionable format like RDF or structured CSV with a published schema [1].2. Ensure persistent identifiers (PIDs) are used for all data elements [33]. |

| Data is published but not discovered by other researchers. | Inadequate metadata for discovery; data not indexed in searchable resources. | 1. Enrich metadata with relevant, standardized keywords and ontologies (e.g., Disease Ontology, NCBI Taxonomy).2. Register the dataset in a public repository and a community-specific registry or search portal [1] [34]. |

| Difficulty integrating your data with other datasets for analysis. | Lack of semantic interoperability; use of local or ad-hoc terminologies. | 1. Map your data to community-accepted ontologies and vocabularies in the semantic modeling step [30] [33].2. Use common data models like those provided by GA4GH for genomic data [32]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing a Data Brokering Model for National Surveillance

The data brokering model, successfully deployed during the COVID-19 pandemic, provides a standardized method for consolidating, curating, and sharing viral genomic data from multiple producers [31].

1. Objective: To establish a centralized national or regional data hub that collects SARS-CoV-2 sequences and associated metadata from multiple sequencing labs, performs quality control and standardization, and brokers the submission to international repositories.

2. Materials and Reagents Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Data Brokering

| Item | Function / Description | Example Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Central Data Platform | A secure computational environment for receiving, storing, processing, and curating incoming data. | SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics COVID-19 Data Platform [31], CNT (Spanish National Center for Microbiology) platform [31]. |

| Standardized Metadata Sheet | A template (e.g., a CSV or TSV file) with controlled vocabulary to ensure consistent metadata collection from all data providers. | Template based on INSDC pathogen package or GA4GH metadata standards [32]. |

| Curation & Validation Pipelines | Automated workflows (e.g., Galaxy workflows, Snakemake, Nextflow) to check sequence quality, metadata completeness, and format compliance. | Custom scripts, Galaxy Project SARS-CoV-2 analysis workflows [31], FAIRplus validation tools [33]. |

| Submission Connectors | Software tools or APIs that facilitate the automated or semi-automated submission of curated data to international repositories. | Custom API scripts for ENA/GISAID submission, ELIXIR's Data Submission Service [31]. |

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Coordination and Agreement. Engage with data-producing labs (e.g., clinical, public health) to establish a common agreement on the data brokering process, data standards, and sharing policies [31].

- Step 2: Data and Metadata Collection. Labs submit raw or consensus sequences alongside a filled standardized metadata sheet to the central data platform.

- Step 3: Centralized Curation. The data brokering team runs automated pipelines to validate file formats, check sequence quality, and ensure metadata completeness. They may also perform additional analyses (e.g., lineage assignment) [31].

- Step 4: Data Anonymization/Pseudonymization. If required, sensitive information is removed or pseudonymized in accordance with the agreed legal and ethical framework [33] [32].

- Step 5: Brokering to Repositories. The curated and anonymized data is submitted on behalf of the producers to international repositories like the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) and/or GISAID, as per the data providers' preferences [31].

- Step 6: Feedback and Reporting. The data brokering platform provides feedback and tailored reports (e.g., lineage reports) back to the data-producing labs and public health authorities.

The workflow for this protocol is depicted below:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Resources for Viral Genomic Data FAIRification

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Standard | Role in FAIRification Process |

|---|---|---|

| FAIRification Frameworks | FAIRplus Framework [33]GO-FAIR 3-Point FAIRification Framework [1] | Provides a structured, step-by-step methodology and templates for planning and executing a FAIRification project. |

| Semantic Standards & Ontologies | NCBI TaxonomyDisease Ontology (DOID)Environment Ontology (ENVO)GA4GH Phenopackets [32] | Provides standardized, machine-readable terms for describing data (e.g., virus strain, host, sampling environment), enabling interoperability. |

| Data & Metadata Models | INSDC Pathogen PackageGA4GH Metadata Standards [32] | Defines the structure and required fields for sequence data and associated metadata, ensuring consistency and completeness. |

| Data Repositories & Platforms | European Nucleotide Archive (ENA)GISAIDEU Covid-19 Data Portal [31] | Provides a FAIR-compliant hosting environment with unique identifiers (PIDs), searchable indexes, and standardized access protocols (APIs). |

| Implementation Guides | The FAIR Cookbook [33]Galaxy Project Workflow FAIRification Tutorial [34] | Offers practical, hands-on "recipes" and tutorials for implementing specific FAIRification steps, such as data transformation and workflow annotation. |

Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) for Viral Sequence Data

FAQs on PIDs

Q1: What is a Persistent Identifier and why is it critical for our viral sequence data? A Persistent Identifier (PID) is a long-lasting reference to a digital resource, consisting of a unique identifier and a service that locates the resource over time, even when its physical location changes [35]. For viral sequence data, PIDs are critical because they:

- Establish Provenance: Help verify that the data is what it purports to be [35].

- Ensure Stable Access: Provide a stable link to your data, overcoming the problem of broken links (link rot) common with standard URLs [35] [36].

- Enable Proper Citation: Allow your data to be uniquely cited in publications, giving you credit for your work [37] [36].

Q2: Which PID scheme should I choose for depositing viral sequences? The choice of scheme depends on your repository and specific needs. The table below summarizes the main schemes:

| PID Scheme | Full Name | Key Characteristics | Common Use in Life Sciences |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOI [35] | Digital Object Identifier | A specific type of Handle; very well-established and widely deployed; has a system infrastructure for reliable resolution. | Journal articles, datasets (via DataCite), making research outputs citable [37] [36]. |

| Handle [35] | Handle | A system for unique and persistent identifiers; forms the technical infrastructure for DOIs. | Underpins the DOI system; used in various digital repository applications. |

| ARK [35] | Archival Resource Key | An identifier scheme emphasizing that persistence is a matter of service, not just syntax. | Often used by libraries and archives for digital objects. |

| PURL [35] | Persistent URL | A URL that permanently redirects to the current location of the web resource. | Providing stable links for web resources that may change locations. |

For viral sequence data submitted to major public repositories like the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) or GenBank, a DOI is often assigned or can be requested, making it the de facto standard for data citation [37].

Q3: I have a PID for my dataset, but the link is broken. What should I do? This is a failure of the resolution service. First, check the PID in your web browser. If it fails:

- Contact the PID Provider: If it's a DOI, contact the registration agency (e.g., DataCite or Crossref) or the repository that issued it (e.g., SRA).

- Verify the Metadata: Log in to the provider's service and ensure the URL in the PID's metadata is correct and up-to-date. Persistence requires ongoing maintenance of this link [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: PID Resolution Failure

- Symptom: Clicking a PID (e.g., a DOI link) returns a "404 Not Found" error.

- Diagnosis: The metadata associated with the PID points to an incorrect or outdated URL.

- Solution:

- Identify the issuing organization (e.g., from the DOI prefix).

- Navigate to the resolver service's website (e.g., doi.org for DOIs).

- Use the resolver's lookup tool to check the registered target URL.

- If you are the data owner, update the target URL via the provider's administrative interface.

- If you are a data user, report the broken link to the repository where the data is hosted.

Metadata Registries and Ontology Services

FAQs on Metadata and Ontologies

Q1: What is the role of metadata in making viral data FAIR? Rich, machine-readable metadata is the cornerstone of Findability, Interoperability, and Reusability (the F, I, and R in FAIR) [1] [38]. For viral sequences, it allows both humans and computers to:

- Find data based on specific attributes (e.g., virus species, host, collection date, geographic location) [1].

- Understand the context and methods of the experiment (provenance) [38].

- Integrate datasets from different sources for combined analysis [1].

Q2: How can ontologies help annotate our viral sequencing metadata? Ontologies are machine-processable descriptions of a domain that use standardized, controlled vocabularies [39]. They solve the problem of inconsistent terminology (e.g., "H1N1," "Influenza A virus H1N1," "Influenza A (H1N1)") by providing unique identifiers for each concept. This enables:

- Interoperability: Different datasets using the same ontology terms can be seamlessly integrated and queried [1] [39].

- Advanced Querying: You can query data based on semantic meaning, finding all data related to "influenza virus" even if the specific strain term isn't in the metadata, by leveraging the ontology's hierarchy.

- Semantic Annotation: Tools like the NCBO Annotator can automatically map your free-text metadata to standardized ontological terms [39].

Q3: We want to set up an internal ontology service. Where do we start? You can deploy an open-source service like the EBI Ontology Lookup Service (OLS) in-house [40]. This provides a single point of access to query, browse, and navigate multiple biomedical ontologies, protecting your data and ensuring fast, stable access.

Experimental Protocol: Deploying a Local Ontology Lookup Service (OLS)

This protocol is based on the public OLS deployment guide [40].

Objective: To deploy a local instance of the EBI OLS to manage and serve ontologies for internal data annotation workflows.

Materials and Software:

- Hardware: A Unix-based (Linux/macOS) or Windows server with sufficient memory and storage.

- Software Dependencies:

- Git (v2.17.1 or higher)

- Docker (v18.09.01 or higher) or Docker Desktop for Windows

- A terminal (PowerShell for Windows)

Methodology:

- Install Dependencies: Ensure Git and Docker are installed and running on your system.

- Clone and Configure OLS:

- Edit the

ols-config.yamlfile to load relevant ontologies (see step 3).

- Edit the

- Load Ontologies: In the

ols-config.yamlfile, add ontology metadata. For example, to load the Data Usage Ontology (DUO):- You can download pre-configured metadata for many public ontologies using a command like:

wget -O ols-config.yaml https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ols/api/ols-config?ids=efo,aero[40].

- You can download pre-configured metadata for many public ontologies using a command like:

- Build and Run the Docker Container:

- Access the Service: Your local OLS will be available at

http://localhost:8080.

Troubleshooting:

- Port Conflict: If port 8080 is busy, use a different port (e.g.,

-p 8081:8080). - Ontology Not Loading: Verify the

ontology_purlin the configuration file is correct and accessible. - Permission Denied: On Unix systems, prefix Docker commands with

sudoif your user is not in the docker group.

Visualizing the Technical Infrastructure Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow between PIDs, metadata, and ontology services in a FAIR-compliant viral data pipeline.

FAIR Data Infrastructure Workflow for Viral Sequences

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Digital Solutions

The following table details key digital "reagents" and services essential for implementing FAIR principles for viral sequence data.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| DataCite DOI [35] [37] | Provides a persistent, citable identifier for research datasets, including viral sequences. | Globally unique, resolvable via https://doi.org, includes rich metadata schema. |

| EBI Ontology Lookup Service (OLS) [40] [39] | A repository and service for browsing, searching, and visualizing biomedical ontologies. | Open-source, can be deployed locally; provides REST API for programmatic access. |

| NCBO Annotator [39] | A web service that maps free-text metadata to standardized terms from ontologies in BioPortal. | Automates metadata annotation; supports semantic enrichment of data descriptions. |

| BioPortal [39] | A comprehensive repository of biomedical ontologies (over 270). | Provides community features like comments and mappings; foundation for the NCBO Resource Index. |

| FAIR Cookbook [40] | A hands-on resource with "recipes" for implementing FAIR principles. | Provides practical, step-by-step guides for technical implementation. |

| Data Reuse Information (DRI) Tag [37] | A machine-readable metadata tag that indicates the data creator's preference for communication before reuse. | Associated with an ORCID; fosters collaboration and equitable data reuse. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DDVD Challenges & Solutions

This guide addresses specific issues researchers might encounter during Data-Driven Virus Discovery experiments.

Issue 1: Low Viral Signal in Public Sequencing Data

Question: My analysis of public sequencing data (e.g., from the SRA) returns very few or no viral sequences. What could be the cause?

Answer: Low viral signal can stem from several sources related to data quality and experimental design of the original datasets you are mining.

- Cause: The source biological samples had low viral load, or the sequencing library preparation method was not suitable for viral nucleic acids.

- Solution: Apply read-level quality control and filtering. Focus on data from samples where viruses are more likely to be present (e.g., tissue from diseased organisms, environmental samples). Use sensitive, alignment-free tools designed for low-abundance sequences.

- FAIR Compliance Note: This highlights the need for rich metadata (Accessibility - A2) to understand sample origin and experimental design, aiding in the selection of appropriate datasets [41] [5].

Issue 2: Challenges in Host Assignment

Question: I have identified a novel viral sequence, but I am unsure how to confidently assign its host organism.

Answer: Host assignment is a common challenge in DDVD. Contamination during sample processing or index hopping can mislead assignments.

- Cause: The viral sequence may be a contaminant rather than a true infection of the sampled host.

- Solution: Implement a confidence framework for host assignment. Guidelines include:

- Detect the viral genome in sequencing experiments from at least two independent laboratories.

- Determine a significant portion of the viral genome for accurate phylogenetic placement.

- Require sufficiently deep read coverage to discriminate actively replicating viruses from contaminants [41].

- FAIR Compliance Note: This underscores the importance of Interoperability (I3), where qualified references to host metadata and phylogenetic context are crucial for accurate biological interpretation [5].

Issue 3: Inability to Detect Highly Divergent Viruses

Question: My similarity-based searches are failing to detect viruses that are highly divergent from known references.

Answer: This is a fundamental limitation of sequence-similarity approaches.

- Cause: Standard BLAST and alignment-based methods rely on significant sequence homology, which may be absent for viruses from deeply branching lineages.

- Solution: Employ a combination of protein-profile searches (e.g., HMMER), gene-agnostic methods (e.g., k-mer frequency analysis), and machine learning approaches that can detect remote homology or viral genomic signatures [41].

- FAIR Compliance Note: Effective discovery of divergent viruses depends on the Reusability (R1) of existing data, which must be curated using community-agreed standards to build comprehensive and accurate profile databases [5].

Issue 4: Different Results from Different Recombinant Detection Tools

Question: When analyzing a potential recombinant viral lineage, I get conflicting results from different computational tools.

Answer: Methods for recombination detection use varying statistical frameworks and have different strengths and weaknesses.

- Cause: Tools may differ in their sensitivity to the number of breakpoints, the length of recombined regions, and the level of sequence divergence between parental lineages.

- Solution: Use a consensus approach. Tools like RecombinHunt, which is data-driven and analyzes mutations against a background of known lineage designations, have shown high concordance with expert manual analysis for SARS-CoV-2 and MPXV. Always corroborate findings with phylogenetic analysis [42].

- FAIR Compliance Note: Reproducible identification of recombinants requires that the data are Findable (F1) and Accessible (A1), with unique identifiers and standardized protocols for retrieval, enabling different methods to be applied consistently [5].

Quantitative Data in Data-Driven Virus Discovery

Table 1: Key Metadata for Confident Viral Sequence Annotation in DDVD

| Metadata Field | Importance for DDVD | FAIR Principle Addressed |

|---|---|---|

| Host Organism | Essential for initial host assignment and understanding ecology. | Interoperability (I2) |

| Collection Date & Location | Critical for temporal and spatial tracking of viruses. | Reusability (R1) |

| Isolate Name | Allows grouping of sequences from the same biological sample. | Findability (F1) |

| Sequencing Technology | Informs on potential errors and data quality assessments. | Reusability (R1) |

| Nucleotide Completeness | Indicates whether the sequence is partial or complete, affecting analyses. | Findability (F2) |

Table 2: Common Tools and Resources for DDVD Workflows

| Tool/Resource Name | Primary Function | Application in DDVD |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI SRA | Public repository of raw sequencing data. | The primary source of data for mining; contained over 10.4 million experiments as of mid-2022 [41]. |

| GISAID | Platform for sharing curated pathogen sequences. | Source of well-annotated viral genomes; exemplifies FAIR implementation with EPI_ISL IDs [5]. |

| RecombinHunt | Data-driven recombinant genome identification. | Identifies recombinant viral genomes (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, MPXV) by analyzing mutation profiles against lineage definitions [42]. |

| NCBI Virus | Integrative portal for searching and analyzing viral sequences. | Provides value-added, curated viral sequence data from GenBank and RefSeq with standardized metadata and filtering [43]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard DDVD Workflow

Objective: To computationally discover and preliminarily characterize novel viral sequences from public sequencing archives.

- Hypothesis & Target Definition: Define the scope of your discovery effort (e.g., "discover novel RNA viruses in arthropod genomes").

- Data Acquisition:

- Identify and download relevant datasets from archives like the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) or the Whole Genome Shotgun (WGS) database based on metadata (host, tissue, etc.) [41].

- FAIR Focus: Ensure data is accessed via standardized, open protocols (Accessibility - A1.1) and that datasets are described with rich metadata (Findability - F2) [5].

- Quality Control & Preprocessing:

- Use tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic to assess read quality and remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases.

- Viral Sequence Identification:

- Method A (Similarity-Based): Map reads to a comprehensive viral database using BLAST or aligners like Bowtie2/BWA. Unmapped reads can be de novo assembled, and contigs are then searched against viral databases.

- Method B (Signature-Based): Use tools that identify viral genomic signatures (e.g., VirFinder, VIRALpro) or perform protein-profile searches (e.g., DRAM-v) to detect divergent viruses.

- Characterization & Validation:

- Host Assignment: Cross-reference the sample's metadata. Use phylogenetic analysis to see if the novel virus clusters with known viruses from a specific host [41].

- Genome Completeness: Assess whether the ends of the viral genome are recovered (e.g., check for partial genes, terminal repeats).

- Recombination Check: Apply tools like RecombinHunt or RDP5 to screen for recombinant sequences, which is crucial for correct evolutionary placement [42].

- Data Submission & Sharing:

- Annotate the new viral sequence with all available metadata and submit it to a public database like GenBank or GISAID.

- FAIR Focus: Upon submission, the sequence receives a unique and persistent identifier (Findability - F1), such as an GenBank accession or GISAID EPI_ISL ID, making it findable for the community [5].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DDVD

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Public Sequence Archives | Foundational data sources for mining. Includes the Sequence Read Archive (SRA), Whole Genome Shotgun (WGS), and Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA) databases [41]. |

| Viral Reference Databases | Curated collections of known viral sequences (e.g., NCBI Viral Genomes, GISAID, ICTV taxonomy) used for comparison and classification. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Essential infrastructure for the highly parallelized computation required to process terabytes of sequencing data efficiently [41]. |

| Controlled Vocabulary & Ontologies | Standardized terms (e.g., for host, tissue) that ensure metadata is consistent, machine-readable, and interoperable across different datasets and tools [5] [43]. |

| Pango Lineage Designations | A dynamic nomenclature system for SARS-CoV-2 that provides a curated list of characteristic mutations, serving as a key input for tools like RecombinHunt [42]. |

Workflow Diagram: The DDVD Process

Recombinant Virus Detection Logic

Integrating FAIR Workflows into Pharmaceutical R&D and Drug Validation Processes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Foundational FAIR Concepts