AI and Machine Learning in Viral Genomics: From Sequencing to Generative Design

This article explores the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) in viral genomics, addressing a critical need for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

AI and Machine Learning in Viral Genomics: From Sequencing to Generative Design

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) in viral genomics, addressing a critical need for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We cover the foundational shift from traditional sequencing to AI-powered analysis, detailing specific methodologies like generative models and ensemble frameworks for antiviral discovery. The content provides insights into troubleshooting data and model challenges and offers a comparative analysis of AI tools for validation. Finally, we examine the future trajectory of the field, including the creation of novel therapeutics and the pressing ethical and safety considerations surrounding AI-designed viral genomes.

The New Paradigm: How AI is Decoding the Language of Viral Genomes

The landscape of viral genomics has been fundamentally reshaped by successive technological revolutions, beginning with the advent of first-generation Sanger sequencing and progressing to the high-throughput capabilities of next-generation sequencing (NGS), now further amplified by artificial intelligence (AI) [1]. This evolution has transformed our capacity to detect, characterize, and track viral pathogens with unprecedented speed and precision. Where traditional methods like Sanger sequencing provided accurate but low-throughput snapshots of viral sequences, NGS enables massively parallel sequencing, offering a comprehensive view of viral populations and their genetic diversity [2] [3]. The latest integration of AI and machine learning into NGS workflows is now pushing the boundaries further, automating complex bioinformatic analyses, enhancing the accuracy of variant calling, and unlocking predictive insights from vast genomic datasets [4]. This application note details the key methodologies and protocols that underpin this evolution, providing researchers with a structured framework for implementing advanced AI-powered viral genome sequencing in their research and drug development programs.

The Shift from Sanger to Next-Generation Sequencing

The transition from Sanger to NGS technologies marks a pivotal shift in viral sequencing capabilities. Sanger sequencing, known for its gold-standard accuracy for short reads, operates on the chain-termination principle using dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) and is ideal for confirming individual variants or sequencing single genes [3] [1]. In contrast, NGS is a massively parallel sequencing approach that can simultaneously sequence millions of DNA fragments, providing unparalleled throughput and discovery power for applications like detecting low-frequency variants and characterizing entire viral populations [2] [1].

Table 1: Key Comparative Characteristics of Sanger and NGS Technologies

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low; sequences a single DNA fragment per reaction [2] | High; sequences millions of fragments simultaneously per run [2] [3] |

| Read Length | Up to ~1,000 base pairs [3] | Short-read: 36-300 bp (e.g., Illumina); Long-read: 10,000-30,000 bp (e.g., PacBio, Nanopore) [1] |

| Primary Applications in Virology | Targeted confirmation of known variants, sequencing specific amplicons [3] | Discovery of novel viruses, genomic epidemiology, detecting low-frequency variants, studying viral quasispecies [2] [5] |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Cost-effective for interrogating a small number of targets (e.g., <20) [2] | Cost-effective for screening large numbers of samples or targets; higher upfront instrument costs [2] [3] |

| Limit of Detection (Sensitivity) | ~15-20% [2] | High sensitivity; can detect variants down to 1% frequency with sufficient depth [2] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Minimal bioinformatics required; relatively simple analysis [3] | Complex; requires sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines and expertise [3] [4] |

The choice between these methods is application-dependent. Sanger remains the preferred method for targeted, low-throughput applications, such as validating a specific mutation identified in an NGS screen. However, for broad, discovery-based viral genomics—including outbreak surveillance, viral evolution studies, and metagenomic pathogen detection—NGS is the unequivocal choice due to its comprehensive coverage and ability to detect the full spectrum of genetic variation within a viral population [2] [3].

Foundational NGS Wet-Lab Workflow for Viral Sequencing

The standard NGS workflow consists of four critical steps that transform a raw biological sample into interpretable genomic data. The following protocol outlines this process for viral genomes.

Protocol: Standard NGS Workflow for Viral Genome Sequencing

Principle: This protocol describes the process to convert viral nucleic acids from a clinical or environmental sample into a sequence-ready library and perform sequencing on an Illumina-based platform, which utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) chemistry with reversible dye-terminators [6] [7].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Library Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolates DNA or RNA from sample matrices (e.g., swabs, tissue, biofluids) [6] [7]. | For RNA viruses, ensure kits include RNA stabilization. For FFPE samples, use specialized kits for degraded nucleic acids [7]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase (for RNA viruses) | Converts viral RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) for library preparation [8]. | Use high-fidelity enzymes to minimize incorporation errors. |

| Fragmentation Enzymes/System | Shears genomic DNA or cDNA into short, random fragments of a defined size (e.g., 200-500 bp) [7]. | Size distribution impacts sequencing efficiency and assembly; optimize for your application. |

| Library Preparation Kit | A master mix containing enzymes and buffers for end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation [7] [8]. | Select kits compatible with your sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina, PacBio). |

| Platform-Specific Adapters | Short, double-stranded oligonucleotides containing sequences complementary to the flow cell primers [7]. | Essential for cluster generation and initiating the sequencing reaction. |

| Index (Barcode) Oligos | Unique short sequences ligated to each sample's DNA fragments [8]. | Enables multiplexing of multiple samples in a single sequencing lane. |

| DNA Clean-up Beads | Purifies nucleic acids between enzymatic steps (e.g., post-fragmentation, post-ligation) [7]. | Magnetic beads are standard for efficient and automated size selection and purification. |

Procedure:

Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Extract total nucleic acids from the sample (e.g., viral transport media, infected tissue) using a commercial kit. The integrity, purity, and quantity of the input material are critical for success [7] [8].

- Quality Control (QC): Assess DNA/RNA purity using UV spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0). Quantify using fluorometric methods for higher accuracy. For RNA, assess integrity via methods like the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) [6] [7].

Library Preparation

- Fragmentation: Fragment the purified gDNA or cDNA to an optimal size (e.g., 200-600 bp) via enzymatic or acoustic shearing [7].

- Adapter Ligation: Repair the ends of the DNA fragments, add an 'A' base to the 3' ends, and ligate platform-specific adapters (e.g., P5 and P7 for Illumina). Include unique dual-index barcodes if multiplexing [7] [8].

- Library Amplification: Perform a limited-cycle PCR to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments and amplify the final library [7].

- QC: Quantify the final library using qPCR for highest accuracy, as it measures amplifiable fragments. Assess size distribution using a bioanalyzer or gel electrophoresis [7].

Clonal Amplification & Sequencing

- Denature the library into single strands and load it onto a flow cell. Fragments bind to complementary lawn oligos.

- Cluster Generation: On an Illumina platform, bound fragments undergo bridge amplification to create millions of clonal clusters, each derived from a single library molecule [7] [8].

- Sequencing by Synthesis: The flow cell is placed in the sequencer. Cycles of fluorescently labeled, reversibly terminated nucleotides are added. After each incorporation, the flow cell is imaged, the base is identified by its fluorescence, and the terminator is cleaved to allow the next cycle. This process is repeated for the desired read length [7] [8].

The AI-Enhanced Bioinformatics Pipeline

The massive datasets generated by NGS necessitate robust bioinformatics. The integration of AI and machine learning is now revolutionizing this phase, moving beyond traditional heuristic methods to models that can learn complex patterns and improve accuracy [4].

Protocol: AI-Powered Bioinformatics Analysis for Viral Detection and SNP Discovery

Principle: This protocol processes raw NGS reads to identify viral sequences and characterize single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within viral populations. It integrates state-of-the-art bioinformatics tools with AI models to enhance accuracy and sensitivity, as demonstrated in a 2024 study [5].

Input: Paired-end FASTQ files from the NGS sequencer. Software Requirements: Cutadapt, SAMtools, MegaHit, BLAST+, Minimap2, pandas, Biopython, and custom Python scripts for AI-enhanced analysis [5].

Procedure:

Quality Control and Adapter Trimming

- Use Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences and perform quality-based trimming.

- Command Parameters: Set a minimum quality score threshold (e.g., Q20) and discard reads shorter than 50 bp after trimming [5].

Host Sequence Depletion

- Align the trimmed reads to the host reference genome (e.g., human, citrus) using an aligner like Minimap2.

- Use SAMtools to separate unmapped reads (which contain potential viral and other non-host sequences) from mapped host reads for downstream viral analysis [5].

Viral Sequence Identification

- Alignment-Based Detection: Map the unmapped reads to a database of known viral reference sequences using BLASTn or BLASTx to identify known viruses [5].

- De Novo Assembly for Novel Viruses: Assemble the unmapped reads de novo using an assembler like MegaHit. The resulting contigs can be queried against databases using BLAST to reveal novel viral sequences or genetic elements not present in reference databases [5].

AI-Enhanced SNP Discovery

- Map the high-quality reads to the identified viral reference genome.

- Use a custom Python script (utilizing the

pandasandpysamlibraries) to compare the entire population of sequenced viral reads to the reference genome base-by-base. - AI Integration: Implement frequency-based filtering and heuristic rules to distinguish true low-frequency SNPs from sequencing errors. More advanced pipelines can employ deep learning models like DeepVariant, which uses a convolutional neural network (CNN) to call genetic variants more accurately than traditional methods, thereby improving the overview of viral genetic diversity [5] [4].

Integrating AI Across the Entire NGS Workflow

The application of AI in viral genomics extends far beyond variant calling, creating a synergistic relationship that enhances every phase of the NGS workflow, from experimental planning to data interpretation [4].

- Pre-Wet-Lab Phase (Experimental Design): AI tools like Benchling and DeepGene assist in strategic planning, predicting experimental outcomes, and optimizing protocols before wet-lab work begins. This includes guiding the design of CRISPR guides for functional viral genomics studies [4] [9].

- Wet-Lab Phase (Automation): AI-driven laboratory automation systems (e.g., Tecan Fluent, Opentrons OT-2) streamline labor-intensive procedures like NGS library preparation. Integrated AI models provide real-time quality control, detecting errors like missing pipette tips or incorrect liquid volumes [4].

- Post-Wet-Lab Phase (Data Analysis): This is where AI has the most profound impact. Cloud-based platforms like Illumina BaseSpace and DNAnexus are incorporating AI/ML tools to make complex analyses accessible without advanced programming skills. Deep learning models excel at identifying subtle patterns in sequencing data, predicting biological functions, and suggesting mechanistic hypotheses for viral pathogenesis and host interactions [4].

Table 3: AI Applications in the Viral NGS Workflow

| NGS Workflow Phase | AI Integration | Impact on Viral Research |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Wet-Lab (Design) | AI-powered design tools (e.g., Benchling, DeepGene) [4] | Optimizes sequencing panel design and predicts outcomes for viral target enrichment. |

| Wet-Lab (Library Prep) | AI-driven liquid handlers and real-time QC (e.g., Opentrons OT-2 with YOLOv8 model) [4] | Automates and improves reproducibility of library prep from diverse sample types (e.g., FFPE, biofluids). |

| Post-Wet-Lab (Analysis) | Deep learning-based variant callers (e.g., DeepVariant) [4] | Increases accuracy of identifying true low-frequency viral variants within a quasispecies. |

| Post-Wet-Lab (Analysis) | Custom Python scripts for SNP analysis and ML-based annotation [5] | Provides a comprehensive view of viral genetic diversity and identifies dominant variants. |

The journey from Sanger sequencing to AI-powered NGS represents a monumental leap in our ability to understand and combat viral pathogens. The foundational NGS workflows provide the high-throughput data generation capacity necessary for detailed viral surveillance and discovery. The emerging layer of AI integration is now refining this process, introducing unprecedented levels of automation, accuracy, and predictive insight. By implementing the detailed protocols for both wet-lab and bioinformatic analyses outlined in this application note, researchers and drug developers can fully leverage these technological synergies. This powerful combination accelerates the pace of viral genomic research, fuels the discovery of novel therapeutics, and enhances our preparedness for emerging viral threats.

Application Notes: AI-Driven Advances in Virology

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally transforming virology research, enabling tasks from de novo viral design and sensitive diagnostics to the large-scale classification of viral sequences. The table below summarizes the core applications and performance metrics of these technologies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Core AI Technologies in Virology

| AI Technology | Application | Reported Performance / Outcome | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Design of viral nanobodies | Creation of 92 novel nanobodies; two with improved binding to recent SARS-CoV-2 variants [10]. | Enables sophisticated, interdisciplinary research planning [10]. |

| Deep Learning (CNN) | Prediction of CRISPR diagnostic activity (ADAPT) | auROC = 0.866; accurately predicted diagnostic sensitivity across viral variation [11]. | Optimizes diagnostic sensitivity across the full spectrum of a virus's genomic variation [11]. |

| Deep Learning (Hybrid CNN-BiLSTM) | Identification of viral sequences from metagenomes (DETIRE) | Outperformed other deep learning methods (DeepVirFinder, PPR-Meta, CHEER) in identifying short sequences (<1,000 bp) [12]. | Effectively extracts both spatial and sequential features from short sequences for improved identification [12]. |

| Machine Learning (Random Forest) | Alignment-free viral sequence classification | Achieved 97.8% accuracy classifying 297,186 SARS-CoV-2 sequences into 3,502 distinct lineages [13]. | Enables rapid classification at scale using modest computational resources [13]. |

| Lempel-Ziv Parsing (LZ-ANI) | Viral genome clustering (Vclust) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.3% for tANI estimation; >40,000x faster than VIRIDIC [14]. | Provides high-accuracy, alignment-based clustering for millions of genomes [14]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AI-Driven Design of Viral Nanobodies Using a Virtual Lab

Purpose: To design novel nanobodies against specific viral antigens using a multi-agent LLM system [10].

Experimental Workflow:

Procedure:

- Research Initialization: The human researcher provides high-level feedback and the objective to the Virtual Lab, which consists of an LLM acting as a Principal Investigator guiding a team of LLM scientist agents [10].

- Pipeline Creation: The Virtual Lab agents create a computational nanobody design pipeline. This pipeline incorporates specialized tools:

- Protein Language Model (ESM): Used for understanding protein sequences [10].

- Protein Folding Model (AlphaFold-Multimer): Predicts the 3D structure of the designed nanobodies bound to the viral antigen (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 spike protein) [10].

- Computational Biology Software (Rosetta): Used for energy-based scoring and assessing the stability of the designed nanobodies [10].

- Design and In Silico Analysis: The pipeline designs and scores 92 novel nanobody candidates. The LLM agents discuss results and select promising candidates for experimental testing [10].

- Validation: The selected nanobodies are synthesized and tested experimentally using methods like ELISA to validate binding affinity and specificity against the target viral variants [10].

Protocol: Designing Sensitive Viral Diagnostics with Machine Learning (ADAPT)

Purpose: To design highly sensitive nucleic acid-based diagnostics that are effective across a virus's genomic diversity using a deep learning model [11].

Experimental Workflow:

Procedure:

- Data Generation for Model Training:

- Design a library of 19,209 unique guide RNA–target pairs for a CRISPR-based diagnostic (e.g., using LwaCas13a) [11].

- Measure the fluorescence readout (activity) of each pair using a high-throughput platform like CARMEN (Combinatorial Arrayed Reactions for Multiplexed Evaluation of Nucleic acids) [11].

- Define "activity" as the logarithm of the fluorescence growth rate, which correlates with diagnostic sensitivity [11].

- Model Training:

- Train a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) using a two-step "hurdle model." The model first classifies guide-target pairs as "active" or "inactive," then performs regression to predict the activity level of active pairs [11].

- Diagnostic Design with ADAPT:

- Input the complete genomic variation of a target virus into the ADAPT system [11].

- ADAPT uses the trained CNN model, combined with combinatorial optimization, to select diagnostic assay targets that maximize the predicted sensitivity across the entire spectrum of the virus's known genomic diversity [11].

- Validation: Experimentally test the designed assays against synthetic targets representing known viral variants to confirm sensitivity and specificity [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI Virology

| Item / Tool Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual Lab | An AI-human collaboration platform for interdisciplinary research. | Uses an LLM Principal Investigator to guide a team of specialist AI agents through research cycles [10]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Predicts 3D structures of protein complexes. | Used to model the interaction between a designed nanobody and a viral antigen protein [10]. |

| Rosetta | A suite for computational macromolecular modeling and design. | Used for energy-based scoring and refining designed protein structures (e.g., nanobodies) [10]. |

| ADAPT | A system for automated design of sensitive viral diagnostics. | Combines a deep learning model with combinatorial optimization; designs for 1,933 viral species within hours [11]. |

| CRISPR-Cas13a | An enzyme for RNA-guided RNA targeting used in diagnostics. | The model in ADAPT was trained on data from LwaCas13a guide-target pairs [11]. |

| DETIRE | A hybrid deep learning model for identifying viral sequences from metagenomes. | Combines CNN and BiLSTM to extract spatial and sequential features from short sequences [12]. |

| Vclust | A tool for ultrafast and accurate clustering of viral genomes. | Uses LZ-ANI for alignment and calculates Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) for taxonomy [14]. |

| CRISPR-GPT | An LLM-based copilot for designing CRISPR gene-editing experiments. | Trained on 11 years of expert discussions and papers; assists in design and predicts off-target effects [15]. |

The field of viral genomics is undergoing a transformative shift, moving from simply reading and writing DNA to actively designing it using artificial intelligence (AI). This progression represents a new chapter in our ability to engineer biology at its foundational level [16]. AI models, particularly large language models adapted for genomic sequences, are now capable of generating functional viral genomes by learning the complex "grammar" and "syntax" that govern genetic functionality and evolutionary fitness. These models capture evolutionary constraints well enough to design genomes that not only function but also incorporate substantial novelty beyond what natural evolution has sampled [16]. This capability is proving crucial for addressing pressing global health challenges, including the development of novel antiviral therapies and overcoming bacterial resistance, by providing a systematic approach for staying ahead of pathogen evolution [17] [16].

Core Computational Methodologies

Foundation Model Architecture and Training

The process begins with building genomic foundation models, such as the Evo series, which are trained on massive datasets of natural genetic sequences. These models learn the statistical patterns and biological constraints present in viral genomes, enabling them to generate novel, coherent sequences that maintain biological functionality.

Training Data Curation:

- Base Models: Trained on over two million phage genomes to learn general principles of viral genome organization [16].

- Specialized Fine-Tuning: Continued training on curated, non-redundant datasets specific to the target viral family (e.g., 14,466 Microviridae sequences clustered at 99% identity for bacteriophage ΦX174 design) [16].

- Data Accessibility: Cloud-based genomic platforms now connect over 800 institutions globally, with more than 350,000 genomic profiles uploaded annually, providing vast data resources for training these algorithms [18].

Specialized Fine-Tuning for Genome Generation

While base models possess general sequence generation capabilities, they lack the controllability needed for specific genome design. This is achieved through supervised fine-tuning, a process that specializes the model on sequence variation closely related to a specific design template.

Key Fine-Tuning Strategies:

- Template-Based Design: Using a well-characterized virus (e.g., bacteriophage ΦX174) as a design template provides clear design criteria and sits at a practical limit for DNA synthesis costs [16].

- Prompt Engineering: Developing precise sequence prompts and sampling parameters to guide the model to generate sequences that phylogenetically resemble the template while allowing for substantial evolutionary divergence [16].

- Overlapping Gene Handling: Custom annotation pipelines are developed to handle complex gene architectures, such as overlapping reading frames, which confound standard gene prediction tools [16].

Quality Control and Filtering Pipelines

Evaluating thousands of AI-generated sequences requires robust multi-stage filtering to select candidates for experimental validation.

Table 1: Key Filters for AI-Generated Genome Selection

| Filter Category | Criteria | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Quality | Retention of core genetic toolkit; prediction of at least 7 of 11 natural ΦX174 proteins via custom annotation pipeline [16]. | Homology searches against phage protein databases; ORF finding strategies. |

| Host Specificity | Conservation of key host-range determinants (e.g., spike protein for ΦX174) to ensure infection of target bacteria (E. coli C) [16]. | Sequence alignment and motif conservation analysis. |

| Evolutionary Novelty | Allowing 67–392 novel mutations compared to nearest natural genome; incorporation of sequences not found in nature [16]. | Phylogenetic analysis and BLAST against genomic databases. |

Experimental Validation Protocol

High-Throughput Functional Screening

A critical phase is the experimental testing of AI-designed genomes to separate functional sequences from non-functional ones. This requires rethinking traditional workflows for high-throughput efficiency [16].

Protocol 3.1: Growth Inhibition Assay for Synthetic Phages

- Objective: To rapidly identify functional phage genomes from hundreds of AI-generated designs based on their lytic activity.

Materials:

- Synthesized and assembled AI-generated phage genomes.

- Competent E. coli C culture (non-pathogenic host strain).

- 96-well plates for high-throughput culturing.

- Spectrophotometer for measuring optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀).

Method:

- Genome Assembly: AI-designed genomic sequences are chemically synthesized and assembled into complete genomes via Gibson assembly [16].

- Transformation: Assembled genomes are transformed into competent E. coli C cells [16].

- Growth Monitoring: Transformed cultures are monitored for growth inhibition in a 96-well format. Successful phage infection and replication cause host cell lysis, leading to a characteristic rapid decline in OD₆₀₀ within 2–3 hours [16].

- Candidate Selection: Cultures showing significant growth inhibition are selected as potential functional phage candidates for further verification.

Sequence Verification and Characterization

Protocol 3.2: Validation of Functional Phages

- Objective: To confirm the sequence and characterize the basic biology of AI-generated phages that pass the initial screen.

- Method:

- Sequence Verification: Functional phage candidates are propagated, and their genomic DNA is sequenced to confirm it matches the AI-designed sequence and to identify any unintended mutations [16].

- Host Range Determination: The specificity of validated phages is tested against a panel of bacterial strains (e.g., E. coli C, E. coli W, and six other related strains) to ensure host specificity has been maintained [16].

- Structural Analysis: For phages with novel protein incorporations (e.g., the J protein from distantly related phage G4), techniques like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) can be used to reveal how these novel proteins integrate into the viral structure [16].

Advanced Application: Overcoming Bacterial Resistance

Protocol 3.3: Phage Cocktail Evolution Assay

- Objective: To leverage AI-generated phage diversity to overcome evolved bacterial resistance.

- Method:

- Resistance Induction: Generate ΦX174-resistant E. coli strains (e.g., with mutations in the waa operon affecting bacterial surface receptors) [16].

- Cocktail Challenge: Expose the resistant bacteria to a cocktail containing multiple distinct AI-generated phage designs.

- Serial Passage: Perform 1-5 serial passages of the phage cocktail on the resistant bacterial strain.

- Isolation and Sequencing: Isolate phages that successfully overcome the resistance and sequence their genomes. The breakthrough phages are often mosaic genomes derived from recombination between multiple AI designs, with mutations concentrated in surface-exposed regions that interact with bacterial receptors [16].

Essential Data Analysis and Machine Learning Frameworks

Beyond de novo genome design, AI and machine learning (ML) play a crucial role in analyzing viral sequences for drug discovery. Ensemble frameworks that integrate compound structural data with viral genome sequences can identify both virus-selective and broad-spectrum pan-antiviral agents [17].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Antiviral Prediction Models

| Model Type | Machine Learning Algorithm | Key Performance Metrics | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus-Selective | Random Forest (RF) | AUC-ROC = 0.83 ± 0.02, Balanced Accuracy (BA) = 0.76 ± 0.02, MCC = 0.44 ± 0.04 [17]. | Predicts active compounds for a specific virus. |

| Virus-Selective | eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) | AUC-ROC = 0.80 ± 0.01, BA = 0.74 ± 0.01, MCC = 0.39 ± 0.02 [17]. | Predicts active compounds for a specific virus. |

| Pan-Antiviral | Random Forest (RF) | AUC-ROC = 0.84 ± 0.02, BA = 0.79 ± 0.02, MCC = 0.59 ± 0.04 [17]. | Predicts broad-spectrum antiviral activity. |

| Pan-Antiviral | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | AUC-ROC = 0.83 ± 0.03, BA = 0.79 ± 0.03, MCC = 0.58 ± 0.05 [17]. | Predicts broad-spectrum antiviral activity. |

Input Features for Models:

- Compounds: Represented as 1024-bit ECFP4 fingerprints [17].

- Viral Genomes: Represented as 100-dimension vectors derived from complete genome assemblies [17].

Table 3: Essential Materials for AI-Driven Viral Genomics Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| AI Model (Evo) | Genomic foundation model for generating viral genome sequences [16]. | Pre-trained on millions of viral sequences; requires fine-tuning on target data. |

| Bacteriophage Template | Well-characterized template for genome design projects [16]. | ΦX174 (5,386 nt), historically significant and practical for synthesis. |

| Non-Pathogenic Bacterial Host | Safe host for functional testing of synthetic phages [16]. | E. coli C or other common laboratory strains. |

| Custom Gene Annotation Pipeline | Identifies genes in complex genomes, especially those with overlapping reading frames [16]. | Combines ORF-finding with homology searches. |

| Approved/Investigational Antiviral Drugs (AIADs) | Curated dataset for training machine learning models for antiviral discovery [17]. | 303 compounds from sources like DrugBank. |

| Cloud-Based Genomic Platform | Provides computational power and data integration for AI analysis [18]. | Illumina Connected Analytics, AWS HealthOmics. |

| High-Throughput Synthesis & Assembly | Chemical synthesis and assembly of AI-designed genomes for testing [16]. | Gibson assembly in 96-well format. |

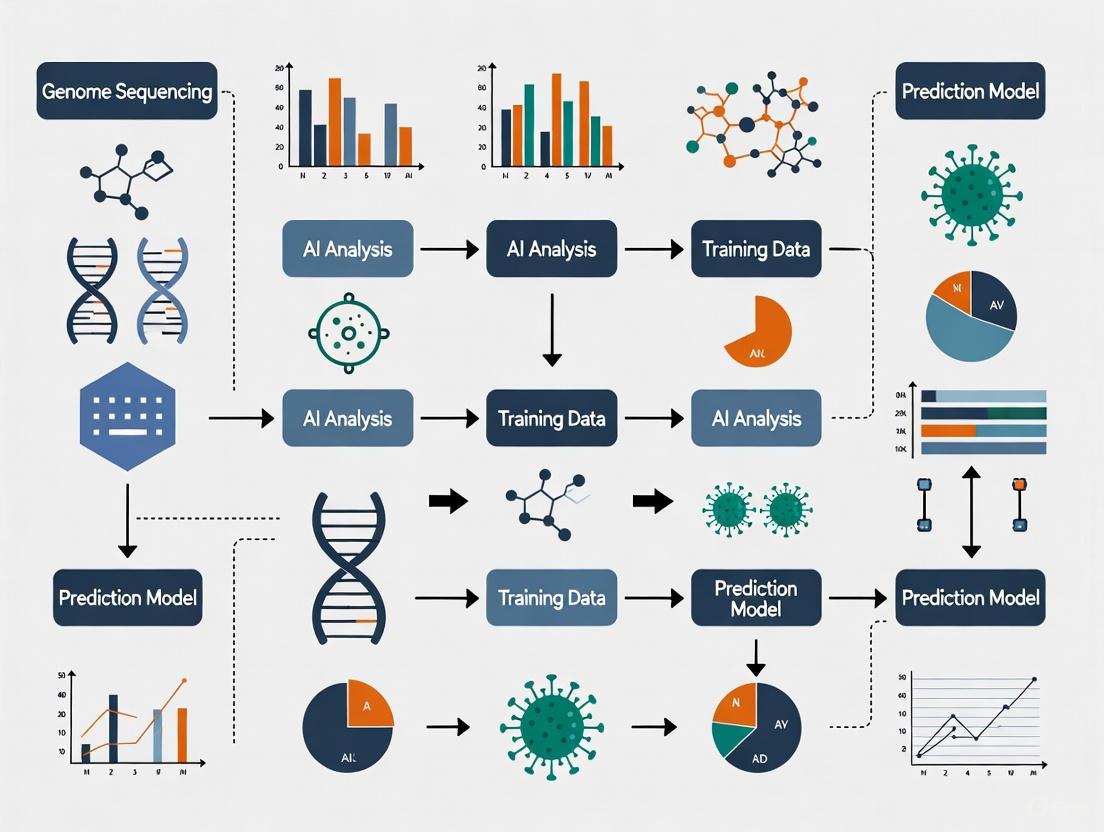

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for generating and validating AI-designed viral genomes:

Application Note 1: AI-Enhanced Genomic Diagnostics and Variant Characterization

Artificial intelligence significantly augments the diagnostic process for viral pathogens by enabling the rapid identification and functional characterization of genomic variants from sequencing data. Traditional methods, which rely on manual curation and reference-based alignment, struggle with the volume and complexity of data generated by modern sequencing technologies. AI models, particularly deep learning, automate the variant calling process with superior accuracy, distinguish between significant mutations and benign variations, and predict the potential impact of these variants on viral transmissibility, virulence, and immune evasion [19] [20]. For instance, tools like DeepVariant employ deep learning to transform sequencing data into image-like representations, enabling highly accurate identification of insertions, deletions, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that might be missed by conventional methods [19].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AI-Assisted Functional Characterization of Novel Variants

Objective: To identify and prioritize mutations in a viral genome (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) that may confer functional advantages, such as enhanced binding affinity or antibody escape.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Obtain a dataset of viral genome sequences, typically in FASTA format, from public repositories like GISAID, NCBI, or EBI [17].

- Perform multiple sequence alignment against a reference genome (e.g., NC_045512.2 for SARS-CoV-2) to identify mutations.

- Annotate mutations based on their genomic location (e.g., Spike protein, RdRp).

Feature Engineering:

- Encode genomic sequences into numerical feature vectors suitable for machine learning. Common techniques include:

- k-mer frequency counts: Fragment sequences into overlapping k-mers (e.g., 3-mers, 4-mers) and count their occurrence.

- One-hot encoding: Represent each nucleotide (A, C, G, T, U) as a binary vector.

- Integrate structural features if available, such as changes in protein stability or solvent accessibility predicted by tools like AlphaFold [9] [20].

- Encode genomic sequences into numerical feature vectors suitable for machine learning. Common techniques include:

Model Training and Prediction:

- Train a machine learning model, such as a Random Forest (RF) or eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) classifier, on a curated dataset of known functional and neutral variants [17].

- Input features include the encoded genomic data and associated structural features.

- The model outputs a probability score predicting the functional impact of a novel variant (e.g., high, medium, low risk).

Validation:

- Validate predictions using in vitro assays, such as:

- Pseudovirus Entry Assay: To confirm the impact of Spike protein mutations on viral infectivity and cell entry [17].

- Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT): To assess the variant's resistance to neutralizing antibodies from convalescent or vaccinated sera.

- Validate predictions using in vitro assays, such as:

Table 1: Representative AI Models for Genomic Analysis

| Model/Tool | AI Methodology | Primary Application | Reported Performance (AUC-ROC) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepVariant | Deep Learning (CNN) | Variant Calling from NGS data | >0.99 [19] | High accuracy in differentiating sequencing errors from true variants. |

| Virus-Selective Model | Ensemble Random Forest | Identifying antiviral agents for specific viruses | 0.83 ± 0.02 [17] | Integrates viral genome sequences with compound structures. |

| Pan-Antiviral Model | Random Forest / SVM | Identifying broad-spectrum antiviral agents | 0.84 ± 0.02 / 0.83 ± 0.03 [17] | Predicts activity across multiple virus families. |

AI-Driven Variant Analysis Workflow: This diagram outlines the key steps from sample to functional insight, highlighting AI-driven components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for AI-Guided Genomic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits | Generate unbiased sequencing data from viral RNA. | Amplicon sequencing (e.g., COVIDSeq) for whole viral genome coverage [21]. |

| Variant Calling Software | Base algorithm for initial variant identification. | Provides raw data for subsequent AI-based refinement and analysis [19]. |

| Curated Genomic Databases | Provide labeled data for model training and benchmarking. | Sources like GISAID are used to train models to recognize significant mutations [17]. |

| Pseudovirus System | Safe, non-replicating viral particles for functional testing. | Validates the impact of Spike protein mutations on cell entry predicted by AI models [17]. |

| Protein Structure Prediction Tools | Computationally model 3D protein structures from sequences. | AlphaFold is used to predict how mutations alter protein structure and function [9] [20]. |

Application Note 2: AI-Powered Genomic Surveillance and Outbreak Tracking

The integration of AI with viral genome sequencing has revolutionized the field of epidemic intelligence, transforming it from a reactive to a proactive discipline. AI systems can process vast volumes of disparate data—including genomic sequences from platforms like Illumina, clinical reports, and unstructured data from news sources and social media—in near real-time [22] [23]. This allows for the early detection of emerging outbreaks, the tracking of pathogen spread across regions, and the reconstruction of transmission chains with high resolution. Systems like HealthMap and EPIWATCH demonstrated this capability by flagging the initial COVID-19 outbreak ahead of official announcements, while the VISTA project uses AI to rank the spillover and pandemic potential of viruses from animal reservoirs [22] [24].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Real-Time Phylodynamic Analysis for Outbreak Investigation

Objective: To reconstruct the transmission dynamics and geographic spread of a viral outbreak using genomic data and machine learning.

Methodology:

- Genomic Data Collection and Curation:

- Continuously aggregate viral genome sequences from local, national, and international surveillance efforts (e.g., wastewater surveillance, clinical testing) [21].

- Annotate each sequence with rich metadata, including sample collection date, geographical location, and patient clinical outcomes.

Phylogenetic Inference:

- Perform multiple sequence alignment of the collected genomes.

- Construct a phylogenetic tree using maximum-likelihood or Bayesian methods to visualize the evolutionary relationships between viral samples.

AI-Enhanced Spatio-Temporal Analysis:

- Employ machine learning models, such as EpiLLM or other spatio-temporal architectures, that integrate the phylogenetic data with mobility patterns and epidemiological data [23].

- These models identify clusters of genetically similar viruses and infer the direction and rate of spread between geographic hubs.

Resource Optimization:

- Use the outputs of the phylodynamic model to inform reinforcement learning algorithms, which can optimize the allocation of public health resources, such as testing kits and vaccines, to areas at highest risk of importation or exponential growth [25].

Table 3: AI-Driven Surveillance Platforms and Their Functions

| Platform/System | Core AI Technology | Primary Function | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| HealthMap | Natural Language Processing (NLP), Machine Learning | Automated global outbreak detection | Online news, social media, official reports [22] |

| VISTA/BEACON | Large Language Models (LLMs), Expert Curation | Ranking virus spillover and pandemic potential | Open-source data, viral genomic databases, expert opinion [24] |

| EDS-HAT | Machine Learning | Detecting hospital-borne infection outbreaks | Electronic Health Records (EHRs), Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [22] |

| EpiLLM | Multi-modal LLM, Spatio-temporal modeling | Localized prediction of disease spread | Genomic data, mobility data, epidemic trends [23] |

AI-Powered Genomic Surveillance System: This diagram illustrates how AI synthesizes diverse data streams to generate actionable public health intelligence.

Application Note 3: Understanding Viral Evolution and Informing Countermeasures

AI provides a powerful framework for modeling the evolutionary trajectory of viruses and accelerating the development of countermeasures, such as antiviral drugs and vaccines. By analyzing patterns across vast datasets of viral sequences and compound structures, machine learning models can predict the emergence of drug-resistant strains and identify novel, broad-spectrum antiviral candidates in silico before they are tested in the lab [17]. This approach dramatically compresses the drug discovery timeline, which is critical during a pandemic. Furthermore, AI models like AlphaFold have revolutionized structural biology by accurately predicting the 3D structures of viral proteins, thereby illuminating potential drug targets and the mechanistic impact of evolutionary mutations [9] [20].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening for Antiviral Discovery

Objective: To rapidly identify potential antiviral compounds against a novel or evolving virus using quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models.

Methodology:

- Dataset Curation:

- Active Compounds: Compile a list of approved and investigational antiviral drugs (AIADs) from databases like DrugBank [17].

- Inactive Compounds: Select a set of non-cytotoxic pharmaceutical compounds (NCPCs) with no known antiviral activity to serve as negative controls [17].

- Viral Genomes: Gather complete genome assemblies of the target virus and related viruses.

Molecular Representation:

- Encode the chemical structures of all compounds into numerical fingerprints, such as 1024-bit ECFP4 (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint) fingerprints, which capture molecular features [17].

- Encode viral genome sequences into numerical descriptors.

Model Training and Validation:

- For virus-selective models, train an ensemble model (e.g., Random Forest) using both compound fingerprints and viral genome descriptors as input features. The model learns to predict activity for a specific virus [17].

- For pan-antiviral models, train a QSAR model (e.g., SVM or RF) using only compound fingerprints to identify broad-spectrum antiviral activity [17].

- Validate model performance using cross-validation, with metrics like AUC-ROC, Balanced Accuracy (BA), and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC).

Virtual Screening and Experimental Confirmation:

- Apply the trained models to screen large virtual compound libraries (e.g., ~360,000 compounds) [17].

- Select top-ranking compounds for in vitro testing in assays such as a pseudotyped particle (PP) entry assay and an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) assay to confirm antiviral activity and potency [17].

AI-Driven Antiviral Discovery Pipeline: This workflow shows the process from model training based on known compounds to the experimental validation of AI-prioritized candidates.

From Data to Discovery: Practical AI Methods for Genome Analysis and Antiviral Development

The escalating global threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has intensified the search for alternatives to conventional antibiotics, with bacteriophage (phage) therapy emerging as a particularly promising candidate [26]. However, the natural diversity of phages and their bacterial hosts presents a significant challenge for developing standardized, effective therapies. The nascent convergence of synthetic biology, artificial intelligence (AI), and viral genomics is forging a new path to address this challenge. This Application Note details how generative AI models, specifically genome language models like Evo, are being used to design novel, functional bacteriophage genomes de novo. This approach represents a paradigm shift from simply discovering phages in nature to actively engineering them, enabling the creation of phages with tailored properties for therapeutic and research applications [16] [27]. By providing detailed protocols and frameworks, this document serves as a guide for researchers aiming to leverage AI for advanced viral genome design within a broader research context of AI and machine learning for viral genome sequencing.

Generative AI for Phage Genome Design: Core Concepts and Workflow

Generative AI for genome design involves using large language models (LLMs) trained on vast datasets of biological sequences to create novel, coherent genetic sequences. Unlike traditional genetic engineering, which modifies existing templates, this approach can generate entirely new genomes that remain functional while incorporating significant evolutionary novelty [27]. The Evo model series exemplifies this technology. Evo is a foundational genome language model pretrained on a massive corpus of over 9.3 trillion nucleotides from 128,000 diverse organisms, allowing it to learn the complex "syntax" and "grammar" of DNA [16] [27].

A critical challenge in whole-genome design is orchestrating multiple interacting genes and regulatory elements while maintaining functional balance. This is particularly stringent in phages like ΦX174, which feature overlapping genes where a single nucleotide can be part of multiple protein-coding sequences [16]. The workflow for generating viable phage genomes involves a multi-stage computational and experimental process, summarized in the diagram below.

Figure 1: End-to-end workflow for AI-driven design and validation of novel bacteriophage genomes, illustrating the sequence from model training to experimental confirmation.

Model Training and Sequence Generation

The base Evo model requires specialization to generate viable, family-specific phage genomes. This is achieved through supervised fine-tuning on a curated dataset of target phage family sequences. For ΦX174-like phages, researchers used 14,466 Microviridae genomes, clustered at 99% identity to reduce redundancy [16]. This process specializes the model's knowledge, enabling it to generate sequences that are phylogenetically related to the template without being mere replicas. Sequence generation is typically initiated through a prompting strategy, where a conserved "seed" sequence from a well-characterized phage (e.g., ΦX174) is provided, and the model is instructed to generate the remainder of the genome [27]. This approach balances creative generation with the constraint of essential functional elements.

Computational Filtering and Quality Control

Thousands of AI-generated sequences must be computationally filtered to eliminate non-viable candidates before costly synthesis. This requires developing custom annotation pipelines, especially for phages with overlapping genes that confound standard gene prediction tools [16]. Key filtering criteria include:

- Sequence Length: Filtering for genomes within a practical size range (e.g., 4,000–6,000 bases for ΦX174-like phages) [27].

- Gene Content: Requiring a minimum number of predicted essential genes (e.g., at least 7 of the 11 genes in ΦX174) [16].

- Host Specificity: Ensuring the presence of critical elements for host infection, such as a conserved spike protein sequence that determines host range [16].

- Novelty Assessment: Using tools like

fastANIandEzAAIto calculate Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) and Average Amino acid Identity (AAI) against natural genomes to quantify evolutionary novelty [28].

Quantitative Data on AI-Designed Phages

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent breakthrough studies on AI-generated bacteriophages, highlighting the performance of the models and the characteristics of their functional outputs.

Table 1: Performance of Generative AI Workflow for ΦX174-like Phage Design

| Workflow Stage | Input/Metric | Value | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Generation | Initial candidate genomes generated | 302 | Distinct candidates after initial filtering [27] |

| In vitro Synthesis | Genomes successfully assembled | 285 | Out of 302 designed, via chemical synthesis and Gibson assembly [27] |

| In vivo Validation | Viable, replicating phages | 16 | 5.6% success rate from assembled genomes [27] |

| Evolutionary Novelty | Novel mutations in viable phages | 67 - 392 | Compared to nearest natural genome [16] |

| Minimum ANI of viable phage | 93.0% (Evo-Φ2147) | Qualifies as a new species under some thresholds [16] |

Table 2: Characteristics of Select AI-Designed ΦX174 Phages

| Phage Name | Key Feature | Experimental Performance & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Evo-Φ36 | Gene J swapped from distant phage G4 | Viable despite previous rational engineering failures; cryo-EM showed distinct capsid protein orientation [16]. |

| Evo-Φ69 | Not specified | Outcompeted wild-type ΦX174, increasing to 65x its starting level in a co-culture experiment [27]. |

| Evo-Φ2147 | 392 novel mutations | 93.0% ANI to nearest natural phage (NC51), potentially a new species [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validation of AI-Designed Phage Genomes

This protocol details the experimental steps for synthesizing and validating AI-generated phage genomes, based on the high-throughput methods used to test hundreds of designs [16].

Computational Design andIn SilicoFiltering

- Generate Candidates: Use a fine-tuned Evo model to generate candidate phage genomes by providing a conserved seed sequence from a template phage (e.g., ΦX174).

- Annotate Genomes: Run generated sequences through a custom annotation pipeline (e.g., combining ORF-finding with homology searches against a phage protein database) to identify all essential genes, especially in overlapping reading frames [16].

- Apply Filters: Filter sequences based on:

- Length (e.g., 4,000–6,000 nucleotides).

- Presence of a minimum number of essential genes (e.g., ≥7 for ΦX174).

- Conservation of critical host-range determinants (e.g., spike protein for E. coli C tropism).

- Use

geNomadto confirm viral sequence characteristics [27].

Chemical Synthesis and Genome Assembly

- DNA Synthesis: Send the final list of candidate genome sequences (e.g., 285 designs) to a commercial vendor for chemical synthesis as multiple, overlapping DNA fragments.

- Gibson Assembly: Assemble the full-length genome from the synthesized fragments using Gibson assembly [27], a method that simultaneously joins multiple DNA fragments in a single, isothermal reaction.

- Purification: Purify the assembled linear DNA product to remove assembly reagents.

Transformation andIn VivoBoot-up

- Prepare Competent Cells: Make electrocompetent E. coli C cells, the non-pathogenic host strain for ΦX174.

- Transform: Electroporate approximately 100-200 ng of the purified, assembled phage genome into 50 µL of competent E. coli C cells.

- Recover and Incubate: Immediately add 1 mL of pre-warmed Lysogeny Broth (LB) to the cells after electroporation. Incubate for 3 hours at 37°C with shaking to allow for phage replication and host cell lysis [27].

Functional Validation and Characterization

- Plaque Assay: Centrifuge the culture to pellet cell debris. Serially dilute the supernatant and mix with an early-log-phase culture of E. coli C. Add the mixture to molten soft agar and pour onto a pre-warmed LB agar plate. Incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Identify Viable Phages: Look for clear plaques (zones of lysis) in the bacterial lawn after 16-24 hours. The presence of plaques indicates a viable, lytic phage.

- Sequence Verification: Pick a plaque from each viable design and amplify it. Isolate the phage DNA and sequence it to confirm the genome matches the AI-designed sequence without errors introduced during synthesis or replication.

- Growth Inhibition Assay (High-Throughput): For rapid functional screening, use a 96-well plate growth inhibition assay [16].

- Inoculate E. coli C in TSB to ~1x10⁶ CFU/mL.

- Mix with the candidate phage lysate at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI) (e.g., MOI 20, 2x10⁸ PFU/mL).

- Incubate in a microplate reader at 37°C with agitation, monitoring OD₆₀₀ every 10 min for 6 hours.

- A significant decline in OD₆₀₀ within 2-3 hours indicates successful infection and lysis.

- Characterization: For viable phages, proceed with further characterization, including host range determination, one-step growth curves to assess burst size and latent period, and competitive fitness assays against the wild-type phage [27].

Application in Therapeutic Development

A primary application of AI-designed phages is to overcome the challenge of bacterial resistance. A significant demonstration showed that cocktails of AI-generated phages can overcome resistant bacteria in vitro. In one study, researchers evolved three ΦX174-resistant E. coli strains. While the wild-type ΦX174 failed to inhibit these strains, a cocktail of AI-generated phages overcame resistance in all three strains within 1-5 passages. The breakthrough phages were mosaic genomes derived from multiple AI designs through recombination, with mutations concentrated in surface-exposed regions that interact with bacterial receptors. This highlights a key advantage: AI can generate a diverse population of phages that collectively present multiple targets, making it harder for bacteria to develop comprehensive resistance [16].

Machine learning is also being applied to predict phage-host interactions at the strain level, which is crucial for selecting the right phage for a given bacterial infection. Models trained on protein-protein interaction (PPI) data and host-range datasets have achieved prediction accuracies of 78% to 94% for Salmonella and E. coli phages [28]. Furthermore, AI-driven tools like PhagePromoter are being integrated into pipelines for engineering phages with enhanced therapeutic payloads. These tools use support vector machines (SVM) and artificial neural networks (ANNs) to predict promoter strength, allowing researchers to strategically insert antimicrobial genes into phage genomes at loci that optimize expression timing and level, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for AI-Driven Phage Genome Design and Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example Tools/Organisms |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Genome Language Model | Core AI model for de novo genome sequence generation. Requires fine-tuning for specific phage families. | Evo, Evo 2 (Arc Institute) [16] [27] |

| Computational Annotation Pipeline | Identifies genes, especially in overlapping reading frames, and regulatory elements in generated sequences. | Custom ORF-finder + homology search (e.g., against PHROG database) [16] |

| Host Organism | Non-pathogenic bacterial strain used to "boot up" and propagate synthetic phage genomes. | Escherichia coli C, E. coli W [16] |

| DNA Synthesis & Assembly Method | Reagents and protocols for chemically synthesizing DNA fragments and assembling them into a full genome. | Commercial synthesis + Gibson Assembly [27] |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay | Automated, multi-well method to rapidly test many synthetic genomes for lytic activity. | 96-well plate growth inhibition assay, monitoring OD₆₀₀ [16] |

| Phage-Host Interaction Predictor | Machine learning model that predicts the infectivity of a phage for a given bacterial host genome. | Strain-specific PPI-based ML models [28] [26] |

| Promoter Prediction Tool | ML-based software to identify optimal insertion sites for genetic payloads in phage genomes. | PhagePromoter (SVM & ANN-based) [29] |

The integration of generative AI into viral genome design marks a transformative leap from reading and writing DNA to actively designing it. The successful creation of functional bacteriophages with significant evolutionary novelty using models like Evo provides a blueprint for addressing the antimicrobial resistance crisis through bespoke, engineered phage therapies [16] [27]. The detailed protocols and data frameworks presented in this Application Note offer researchers a foundation to build upon, emphasizing a closed-loop cycle of computational design, high-throughput experimental validation, and model refinement. As these technologies mature, they promise to unlock a new era of synthetic biology where generative AI enables the systematic exploration of genomic possibilities far beyond the reach of natural evolution, paving the way for next-generation biomedical solutions.

Application Notes

The integration of machine learning (ML) with quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and ensemble learning represents a paradigm shift in antiviral drug discovery. This approach enables the rapid virtual screening of vast chemical libraries against viral targets, significantly accelerating the identification of lead compounds. These computational strategies are particularly powerful when applied within a broader research context that leverages viral genome sequencing data to understand and target the molecular basis of viral pathogenesis [17] [20].

A key application is the development of models that can predict both virus-selective and broad-spectrum (pan-) antiviral agents. For instance, one study combined viral genome sequence data with structural information from approved and investigational antiviral drugs to build predictive models. The top-performing ensemble models, based on Random Forest (RF) and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) algorithms, demonstrated robust performance in identifying virus-selective candidates, with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) values of 0.83 and 0.80, respectively [17]. This illustrates the potential of ML to tailor therapeutics to specific viral pathogens.

Concurrently, QSAR models built solely on compound structures (represented as molecular fingerprints) have shown exceptional efficacy in identifying pan-antiviral compounds. These models achieved high predictive accuracy (AUC-ROC > 0.79), allowing researchers to virtually screen massive compound libraries—comprising hundreds of thousands of molecules—for broad-spectrum antiviral activity [17]. The subsequent experimental validation of top-scoring compounds in antiviral assays has yielded hit rates as high as 37% in some cases, underscoring the practical utility of this methodology [17].

The deployment of multimodal feature extraction and ensemble learning frameworks addresses significant challenges in the field, such as the limited availability of experimentally validated active compounds. For example, the MFE-ACVP framework for identifying anti-coronavirus peptides integrates features from sequences, structures, evolution, and topology. By employing an ensemble of traditional ML models and deep neural networks, it achieved an accuracy (ACC) of 77.62% and a Matthew's correlation coefficient (MCC) of 65.19% on an independent validation set, outperforming existing models [30].

These computational approaches are being stress-tested and validated in real-world, collaborative settings. The recent ASAP-Polaris-OpenADMET blind challenge, a community effort focused on pan-coronavirus drug discovery, demonstrated that top-performing AI models can predict molecular potency with near-lab-level precision [31]. Such initiatives provide a crucial benchmark for the field and establish a template for the integration of open science and AI in the rapid development of countermeasures against emerging viral threats.

Quantitative Performance of Representative ML Models in Antiviral Discovery

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of various machine learning models as reported in recent studies for antiviral discovery tasks.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Machine Learning Models for Antiviral Discovery

| Model/Tool Name | Viral Target | Model Type | Key Metric 1 | Key Metric 2 | Key Metric 3 | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus-Selective Model (RF) | Multiple Viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, HCV) | Ensemble (Viral Genome + Compound Structure) | AUC-ROC: 0.83 ± 0.02 | Balanced Accuracy (BA): 0.76 ± 0.02 | MCC: 0.44 ± 0.04 | [17] |

| Virus-Selective Model (XGB) | Multiple Viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, HCV) | Ensemble (Viral Genome + Compound Structure) | AUC-ROC: 0.80 ± 0.01 | BA: 0.74 ± 0.01 | MCC: 0.39 ± 0.02 | [17] |

| Pan-Antiviral Model (RF) | Broad-Spectrum | QSAR (Compound Structure) | AUC-ROC: 0.84 ± 0.02 | BA: 0.79 ± 0.02 | MCC: 0.59 ± 0.04 | [17] |

| i-DENV (SVM for NS3) | Dengue Virus (NS3 Protease) | QSAR Regression | Pearson CC (Training): 0.857 | Pearson CC (Independent Validation): 0.870 | - | [32] |

| i-DENV (ANN for NS5) | Dengue Virus (NS5 Polymerase) | QSAR Regression | Pearson CC (Training): 0.964 | Pearson CC (Independent Validation): 0.977 | - | [32] |

| MFE-ACVP | Coronaviruses (Peptides) | Ensemble (Multimodal Features) | Accuracy (ACC): 77.62% | AUC: 86.37% | MCC: 65.19% | [30] |

Experimental Validation of ML-Predicted Antiviral Compounds

The ultimate test for in silico predictions is in vitro validation. The following table details experimental results from testing compounds identified through machine learning-based virtual screening.

Table 2: In Vitro Assay Results for Compounds Identified by ML Virtual Screening

| Study / Model | Number of Compounds Tested | Assay Type 1 (Hit Rate) | Assay Type 2 (Hit Rate) | Noteworthy Potent Compounds | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble Model for SARS-CoV-2 | 346 | Pseudotyped Particle (PP) Entry Assay: 9.4% (24/256) | RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp) Assay: 37% (47/128) | Top compounds showed potencies around 1 µM | [17] |

| i-DENV (Virtual Screening) | N/A (Computational prioritization for repurposing) | In silico docking confirmed strong binding affinities | - | Top hits: Micafungin, Oritavancin, Cangrelor, Baloxavir marboxil | [32] |

Protocols

Protocol 1: Building an Ensemble QSAR Model for Pan-Antiviral Prediction

This protocol outlines the procedure for developing a robust QSAR model to identify small molecules with broad-spectrum antiviral activity.

Materials and Data Preparation

- Active Compound Set: Curate a collection of known antiviral drugs. For example, the study cited used 303 approved and investigational antiviral drugs (AIADs) from sources like the NCATS in-house collection and DrugBank [17].

- Inactive/Decoy Compound Set: Assemble a set of confirmed inactive or non-cytotoxic compounds to serve as negative controls. The cited study used 385 non-cytotoxic pharmaceutical compounds (NCPCs) from the Tox21 program [17].

- Chemical Structure Standardization: Process all compound structures using a toolkit like RDKit to remove salts, neutralize charges, and generate canonical SMILES strings.

- Molecular Descriptor/Fingerprint Calculation: Encode the chemical structures into a numerical format. The 1024-bit ECFP4 (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint) is a widely used and effective choice for this purpose [17].

Procedure

Data Labeling and Splitting:

- Label all active compounds as 1 and inactive compounds as 0.

- Split the entire dataset into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%), ensuring that all replicates of the same molecule are contained within a single set to prevent data leakage [17].

Model Training with Multiple Algorithms:

- Train multiple machine learning classifiers using the molecular fingerprints as input features. It is recommended to use a diverse set of algorithms, including:

- Optimize the hyperparameters for each algorithm using a technique like ten-fold cross-validation on the training set [32].

Model Validation and Ensemble Construction:

- Evaluate the performance of each trained model on the held-out test set using metrics such as AUC-ROC, Balanced Accuracy (BA), and Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC).

- Select the top-performing models (e.g., the two with the highest AUC-ROC) to form an ensemble. Predictions can be aggregated through averaging or majority voting [17] [30].

Virtual Screening:

- Apply the final ensemble model to screen large, virtual chemical libraries (e.g., ~360,000 compounds [17]).

- Rank compounds based on their predicted probability of being active.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram visualizes the key steps and decision points in the protocol for building a pan-antiviral QSAR model.

Protocol 2: Developing a Virus-Selective Inhibitor Model Using Viral Genomes

This protocol describes a method for creating predictive models that identify inhibitors for specific viruses by integrating chemical and genomic information.

Materials and Data Preparation

- Viral Genome Sequences: Obtain complete genome assemblies for the target viruses and their strains/variants from databases such as GISAID, EBI, and NCBI [17].

- Drug-Virus Interaction Data: Compile a list of known drug-virus pairs, where a pair is labeled 1 if the drug is known to inhibit the virus, and 0 otherwise. The cited study used 378 such positive pairs [17].

- Compound Structures: Gather the structural information for all drugs in the dataset and encode them as ECFP4 fingerprints.

- Viral Genome Feature Extraction: Convert the raw genome sequences (FASTA format) into numerical feature vectors. This can be achieved using natural language processing-inspired techniques or other sequence encoding methods to create 100-dimensional vectors [17].

Procedure

Create a Comprehensive Interaction Matrix:

- Construct a dataset where each sample is a unique drug-virus pair, labeled as active (1) or inactive (0). This will result in a large number of possible combinations (e.g., 3030 from 303 drugs and 10 viruses) [17].

Feature Integration and Selection:

- For each drug-virus pair, concatenate the compound fingerprint and the viral genome feature vector to create a unified input feature set.

- Perform feature selection to reduce dimensionality and minimize noise. Methods like Fisher's exact test and t-test (for RF) or built-in feature importance (for XGB) can be used [17].

Model Training and Optimization:

- Train multiple machine learning models (e.g., RF, XGB, SVM) on the integrated feature set.

- Address class imbalance in the dataset (many more negatives than positives) using techniques like up-sampling the minority class [17].

- Optimize model parameters via cross-validation.

Model Application:

- Use the trained model to predict the activity of new, uncharacterized drug-virus pairs.

- Prioritize drug candidates that show high predicted activity against a specific virus of interest.

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the process of integrating chemical and genomic data to build a virus-selective inhibitor model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs key computational and data resources essential for implementing the machine learning protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Resources for ML-Based Antiviral Discovery

| Resource Name / Type | Specific Example / Format | Function in Research | Citation / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Compound Databases | NCATS In-house Collection, DrugBank, ChEMBL | Provides structural information and bioactivity data for known active and inactive compounds to train and validate ML models. | [17] [32] |

| Viral Genome Databases | GISAID, EBI, NCBI (FASTA files) | Source of genomic sequences for target viruses, enabling the integration of viral genetic information into predictive models. | [17] |

| Molecular Fingerprints | 1024-bit ECFP4 | Converts chemical structures into a numerical bit-string representation, capturing key structural features for machine learning. | [17] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | Core computational engines for building classification and regression models to predict antiviral activity. | [17] [30] [32] |

| Model Validation Metrics | AUC-ROC, Balanced Accuracy (BA), Matthew's Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) | Quantitative measures to assess the performance, robustness, and predictive power of trained models. | [17] [32] |

| In Vitro Validation Assays | Pseudotyped Particle (PP) Entry Assay, RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp) Assay | Biological experiments used to confirm the antiviral activity of compounds identified through virtual screening. | [17] |

The rapid and accurate detection of viruses and the discovery of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are critical for effective disease management, understanding viral evolution, and developing targeted treatments [33]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized genomics by enabling the sequencing of millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, making them thousands of times faster and cheaper than traditional methods [34]. However, the massive volume and complexity of data generated by NGS platforms present significant challenges for analysis using traditional computational approaches [4].

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), with bioinformatics pipelines has created a powerful synergy that addresses these challenges [4] [35]. AI-enhanced pipelines can process raw sequencing data to identify viral sequences with high accuracy and sensitivity, discover novel pathogens, and characterize genetic variations such as SNPs that play crucial roles in disease susceptibility, drug response, and evolutionary adaptation [33] [35]. This integration has transformed virology research, enabling unprecedented capabilities in outbreak surveillance, personalized medicine, and pandemic preparedness [36].

AI-Enhanced Bioinformatics Workflow for Viral Analysis

The automated pipeline for virus detection and SNP discovery from NGS data follows a systematic workflow that integrates state-of-the-art bioinformatics tools with AI algorithms. This comprehensive process transforms raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights through multiple computational stages.

Workflow Visualization

AI-Powered Viral Detection and SNP Discovery Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive pipeline from raw NGS data processing to final biological insights, highlighting the integration of AI components at critical analytical stages [33].

Stage 1: Data Preparation and Quality Control

The initial stage processes raw sequencing data to ensure data integrity and quality for downstream analysis:

- Input Data: Raw paired-end sequencing data in compressed FASTQ format containing forward and reverse reads [33]

- Adapter Trimming: Removal of adapter sequences using Cutadapt tool with minimum quality score threshold of 20 and discarding reads shorter than 50 base pairs after trimming [33]

- Quality Filtering: Application of Phred quality score (Q = -10 × log₁₀P, where P represents the probability of incorrect base call) to exclude low-quality reads [33]

- Read Pairing: Reconstruction of original paired-end reads by aligning forward and reverse reads based on sequence identifiers [33]

Stage 2: Host Genome Filtration and Viral Enrichment

To enhance viral detection sensitivity, host-derived sequences are removed:

- Reference Genome Mapping: Processed reads are aligned to the host reference genome (e.g., Citrus sinensis for plant virology) using Minimap2 aligner [33]

- Alignment Scoring: Minimap2 employs an index-based approach with alignment score calculated as: Match Score × Number of Matches - Mismatch Penalty × Number of Mismatches [33]

- Unmapped Read Collection: Successfully mapped reads (host genome) are discarded, while unmapped reads are preserved for subsequent viral analysis [33]

Stage 3: De Novo Assembly and Viral Detection

This critical stage identifies viral sequences from the filtered data:

- De Novo Assembly: Unmapped reads are subjected to assembly using MegaHit software (version 1.2.9) to reconstruct longer contiguous sequences (contigs) without reference bias [33]

- Viral Sequence Identification: Assembled contigs are compared against viral genome databases using BLAST+ to identify known viral sequences and potentially novel viruses [33]

- AI-Enhanced Classification: Machine learning models can be implemented to improve viral sequence identification, particularly for divergent or novel viruses [35]

Stage 4: SNP Discovery and Analysis

The final analytical stage characterizes genetic variations in detected viruses:

- Variant Calling: A custom Python script compares the entire population of sequenced viral reads to a reference genome to identify SNPs [33]

- Population Genetic Analysis: The approach provides a comprehensive overview of viral genetic diversity, identifying dominant variants and a spectrum of genetic variations [33]

- Functional Impact Assessment: AI tools predict the functional consequences of identified SNPs on viral proteins, pathogenicity, and drug resistance [35]

Performance Metrics and Validation

The effectiveness of AI-powered pipelines is demonstrated through rigorous validation and performance benchmarking:

Quantitative Performance of AI Models in Virology

Table 1: Performance metrics of machine learning models for antiviral discovery and viral sequence analysis

| Model Type | Algorithm | AUC-ROC | Balanced Accuracy | MCC | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus-Selective | Random Forest | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | Identifying virus-specific antiviral compounds [17] |

| Virus-Selective | XGBoost | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | Identifying virus-specific antiviral compounds [17] |

| Pan-Antiviral | Random Forest | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | Identifying broad-spectrum antiviral agents [17] |

| Pan-Antiviral | SVM | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 0.79 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | Identifying broad-spectrum antiviral agents [17] |

| Deep Learning | DeepVariant | >0.99 | N/A | N/A | Variant calling from NGS data [4] |

Experimental Validation Framework

Robust validation is essential to confirm pipeline accuracy and reliability:

- In Vitro Validation: Potential antiviral compounds identified through AI models are validated using pseudotyped particle (PP) entry assays and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) assays, with reported hit rates of 9.4% (24/256) and 37% (47/128) respectively [17]

- Cross-Platform Verification: Results are verified using multiple sequencing technologies (Illumina short-read and Oxford Nanopore long-read) to minimize platform-specific biases [36]

- Benchmarking: Performance comparison against traditional methods (PCR, serological assays) demonstrates superior sensitivity and specificity of AI-powered approaches [33]

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of AI-powered viral genomics requires specific reagents and computational resources:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for AI-powered viral genomics

| Category | Item | Specification/Version | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | DNA-free RNA protocols | Extraction of viral RNA/DNA from diverse sample types [36] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina-compatible | NGS library construction with unique dual indices [36] | |

| Host Depletion Reagents | RNase H-based | Enrichment of viral sequences by removing host nucleic acids [36] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Cutadapt | Version 4.0+ | Adapter trimming and quality filtering of raw reads [33] |

| Minimap2 | Version 2.24+ | Alignment of sequencing reads to reference genomes [33] | |

| MegaHit | Version 1.2.9 | De novo assembly of unmapped reads for novel virus discovery [33] | |

| BLAST+ | Version 2.15+ | Taxonomic classification of assembled contigs [33] | |

| AI/ML Frameworks | DeepVariant | Latest | Deep learning-based variant caller for SNP discovery [4] |

| Scikit-learn | Version 1.3+ | Machine learning algorithms for predictive modeling [17] | |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Version 2.12+ | Deep learning model development and training [35] |

Advanced Machine Learning Applications in Virology

Machine learning approaches applied to viral genome analysis encompass diverse methodologies and data types:

ML Framework for Viral Research

ML Framework for Viral Genome Analysis. This diagram outlines the comprehensive machine learning pipeline from diverse input data sources through feature extraction and modeling to practical virology applications [17] [35].

Implementation Protocols

Detailed methodologies for implementing AI-powered viral analysis:

Protocol for Virus-Selective Antiviral Prediction

- Data Compilation: Collect complete genome assemblies of target virus strains/variants from GISAID, EBI, and NCBI databases [17]

- Compound Curation: Compile approved and investigational antiviral drugs from NCATS in-house collection and DrugBank database [17]

- Feature Representation: Represent compound structures as 1024-bit ECFP4 fingerprints and viral genome sequences as 100-dimension vectors [17]

- Model Training: Implement multiple machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, XGBoost, SVM) with 70/30 training/test split based on unique compounds [17]

- Model Optimization: Apply feature selection (Fisher's exact test, t-test with significance threshold 0.01) and data rebalancing (up-sampling method) [17]

Protocol for De Novo Viral Sequence Discovery

- Sample Processing: Begin with RNA/DNA extraction from clinical or environmental samples, implementing host depletion strategies to enrich viral content [36]

- Library Preparation: Use Illumina-compatible kits for library construction, incorporating unique dual indices to enable sample multiplexing [36]

- Sequencing: Perform paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp) on Illumina platforms, targeting minimum 10 million reads per sample for adequate coverage [33]

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Execute the automated pipeline as detailed in Section 2, with particular emphasis on the de novo assembly step using MegaHit [33]

- Validation: Confirm novel viral sequences through PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of specific regions [33]