Beyond Homology: How AI and Next-Gen Tools Are Revolutionizing Viral Gene Annotation

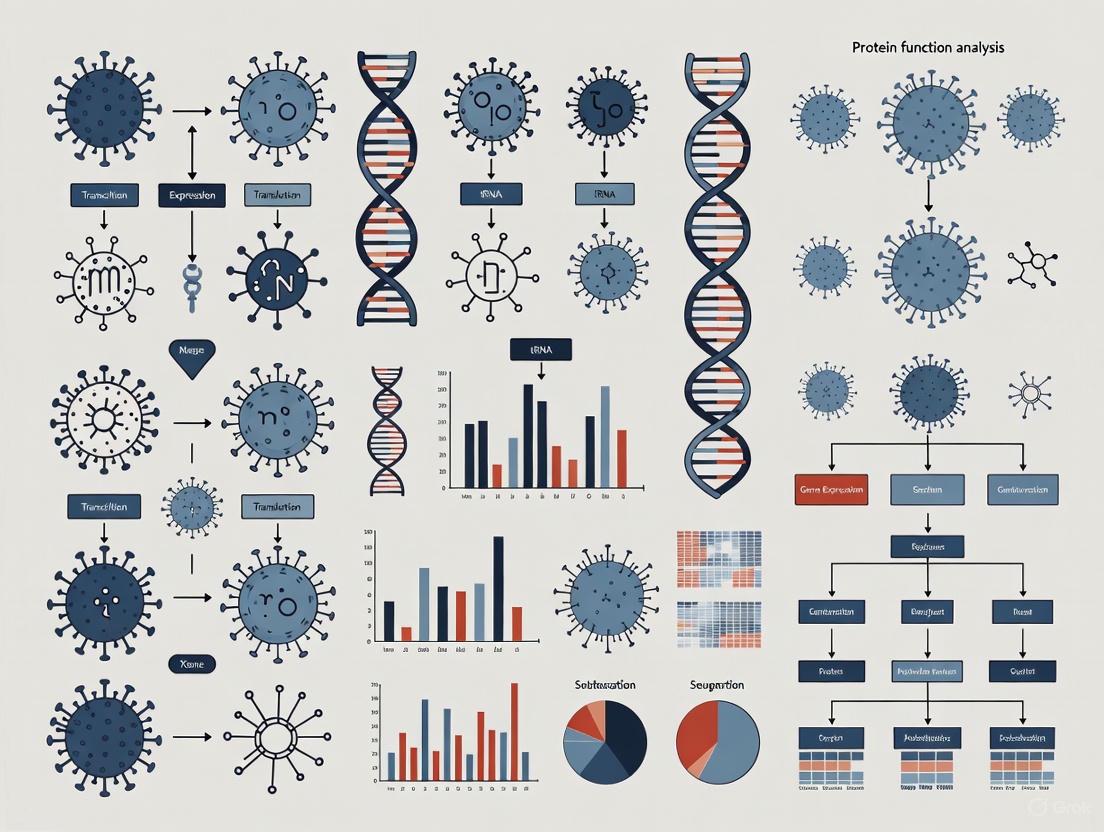

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative computational methods advancing viral gene annotation and protein function analysis.

Beyond Homology: How AI and Next-Gen Tools Are Revolutionizing Viral Gene Annotation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative computational methods advancing viral gene annotation and protein function analysis. It explores the foundational challenges posed by vast viral genetic diversity and the limitations of traditional homology-based tools. The piece details cutting-edge methodologies, including protein language models and specialized bioinformatics pipelines, that are enabling more accurate functional predictions. It further offers practical guidance for troubleshooting common annotation errors and optimizing workflows. Finally, it presents a comparative analysis of modern tools, validating their performance against established benchmarks. This resource is tailored for virologists, bioinformaticians, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage the latest computational advances for viral discovery and characterization.

The Viral Annotation Challenge: Unraveling Genetic Dark Matter

The Scale of Viral Diversity and the 'Viral Dark Matter' Problem

Viral dark matter represents one of the most significant challenges in modern virology, comprising the vast portion of viral sequences that bear no resemblance to characterized viruses or known functional proteins [1]. This fundamental knowledge gap stems from the limitations of traditional homology-based methods when confronted with the immense diversity and rapid evolution of viruses. Metagenomic studies consistently reveal that 40-90% of viral genes lack known homologs or annotated functions, creating a persistent barrier to understanding viral ecology, evolution, and applications [2].

The problem extends beyond mere sequence characterization. This underexplored viral sequence space may encode novel proteins with significant biological functions and biotechnological potential, including auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) that can alter host metabolism during infection [1] [2]. As global metagenomic sequencing efforts accelerate, illuminating this viral dark matter has become both more pressing and more feasible through emerging computational and experimental approaches.

Quantifying the Viral Dark Matter Challenge

The scale of uncharacterized viral diversity becomes apparent when examining data from diverse environments. The following table summarizes findings from recent large-scale metagenomic studies that highlight the extensive novelty discovered across ecosystems:

Table 1: Scale of Viral Dark Matter Across Environments

| Environment | Total Genomes Identified | Novel/Uncharacterized | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tibetan Glacier Ice | 1,705 viral genomes | Majority bore no resemblance to known viruses | [1] |

| Global Ocean Viromes (GOV 2.0) | ~200,000 viral populations | ~12x more than earlier datasets | [1] |

| Deep-sea South China Sea | ~30,000 viral OTUs | >99% lacking close relatives | [1] |

| Qaidam Basin Desert | 2,060 viral MAGs | >94% novel taxa | [3] |

| Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Wildlife | 32 parvoviruses | 9 unclassified to any subfamily | [4] |

The functional annotation gap is equally striking. In curated viral protein databases such as PHROGs, only 5,088 of 38,880 protein families (approximately 13%) have functional annotations, leaving the majority without assigned biological roles [5]. This annotation deficit persists despite increasing sequencing efforts, highlighting that the challenge is not merely data generation but functional interpretation.

Methodological Approaches to Illuminating Viral Dark Matter

Metagenomic Sequencing and Genome Recovery

Protocol: Viral Metagenome-Assembled Genome (vMAG) Recovery

Principle: This protocol enables the identification and characterization of viral sequences directly from environmental samples without cultivation, bypassing the limitations of traditional virological methods [1] [3].

Workflow:

Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect environmental samples (soil, water, feces, etc.) using sterile techniques

- For soil samples, use approximately 30g for DNA extraction with PowerMax Soil DNA Isolation Kit or equivalent

- Assess DNA quality by agarose gel electrophoresis [3]

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare libraries using TruSeqTM DNA PCR-free library Prep Kit

- Set insert fragment length to approximately 400bp

- Perform paired-end sequencing (2 × 150bp) on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform [3]

Bioinformatic Processing:

- Quality control using fastp v1.0.1 to remove adapters and low-quality reads

- Additional trimming using MetaWRAP "Read_qc" module

- De novo assembly using MEGAHIT v1.1.3 with contigs < 2000bp removed [3]

Viral Sequence Identification:

- Identify viral sequences using ViWrap v1.3.1 pipeline with parameters:

--identify_method vb-vs --input_length_limit 5000 - Use intersection of VIBRANT v1.2.1 and VirSorter2 v2.2 results for comprehensive recovery [3]

- Identify viral sequences using ViWrap v1.3.1 pipeline with parameters:

Protein Language Models for Functional Annotation

Protocol: Embedding-Based Viral Protein Annotation

Principle: Protein language models (PLMs) capture functional homology beyond sequence similarity, enabling annotation of divergent viral proteins that evade traditional methods [6] [5].

Workflow:

Embedding Generation:

- Input protein sequences in FASTA format

- Generate embeddings using pre-trained protein language models (ProtT5, ESM2)

- For full proteomes, use FANTASIA pipeline for scalable processing [7]

Function Classification:

Validation and Interpretation:

- Compare predictions with homology-based methods (BLAST, HMMER)

- Assess confidence scores for term transfers

- Visualize alignments using transparent, BLAST-like visualization tools [6]

Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Dark Matter Exploration

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | Illumina (MiSeq, NovaSeq), Oxford Nanopore, PacBio | Generate sequence data from environmental samples | Viral genome recovery; applicable to diverse sample types [1] |

| Assembly Tools | metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT, MEGAHIT | Reconstruct genomes from complex metagenomes | vMAG generation from low-biomass environments [1] [3] |

| Viral Identification | VirSorter2, DeepVirFinder, VIBRANT | Detect viral sequences in assembled contigs | Distinguish viral from microbial sequences; identify integrated proviruses [1] [3] |

| Protein Language Models | ProtT5, ESM2, FANTASIA pipeline | Generate protein embeddings for function prediction | Annotate viral proteins with limited homology to references [7] [5] |

| Functional Databases | PHROGs, UniProtKB, GOA, RVDB | Provide reference annotations for function transfer | Training and validation of annotation pipelines [8] [5] |

| Classification Tools | Kraken2, Kaiju, GTDB-Tk | Taxonomic classification of viral sequences | Determine evolutionary relationships of novel viruses [1] [3] |

Key Findings and Biological Significance

Environmental Discoveries

Recent studies have dramatically expanded known viral diversity through metagenomic approaches. In extreme environments like the Qaidam Basin, a Mars-analog hyperarid desert, researchers recovered 2,060 viral MAGs, with 94% representing novel taxa [3]. Similarly, analysis of Tibetan glacier ice revealed 1,705 viral genomes frozen for approximately 40,000 years, most bearing no resemblance to known viruses [1]. These findings demonstrate that viral dark matter dominates in extreme environments and historical archives.

Functional Insights

Beyond expanding catalogs of viral diversity, new methods are illuminating the functional potential encoded within viral dark matter:

Auxiliary Metabolic Genes (AMGs): Viral metagenomics has uncovered genes that manipulate host metabolism during infection, including genes involved in sulfur cycling, amino acid metabolism, and energy conservation in deep-sea hydrothermal vent viruses [1] [2].

Novel Viral Systems: The discovery of crAssphage through metagenomics revealed a previously unknown bacteriophage that is more abundant in the human gut than all other known phages combined, despite being completely missed by traditional methods [1].

Annotation Advancements

Protein language models have demonstrated remarkable potential for addressing the annotation gap. When applied to global ocean virome data, a PLM-based classifier expanded the annotated fraction of viral protein families by 29% compared to profile HMM-based methods [5]. The FANTASIA pipeline, which uses embedding similarity searches, can annotate up to 50% more proteins in non-model organisms compared to traditional homology-based methods [7].

The viral dark matter problem represents both a fundamental challenge and extraordinary opportunity in virology. While traditional methods have illuminated only a fraction of viral diversity, integrated approaches combining metagenomic sequencing, advanced computational tools, and protein language models are rapidly expanding our understanding of the virosphere. These advances are not merely academic—they enable discovery of novel viral systems with potential applications in biotechnology, medicine, and fundamental biology. As methods continue to evolve, the research community is poised to transform viral dark matter from a taxonomic curiosity into a source of biological insight and innovation.

Limitations of Traditional Homology-Based Methods (BLAST, HMMER)

Homology-based methods are a cornerstone of modern bioinformatics, supporting critical tasks from gene annotation and protein function prediction to evolutionary studies. In viral research, accurately identifying homologous genes is essential for understanding pathogenesis, developing diagnostic tools, and discovering therapeutic targets. For decades, tools like BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) and HMMER have been the workhorses of this field. BLAST uses heuristics to find high-scoring local alignments between a query sequence and a database, while HMMER employs profile Hidden Markov Models (profile HMMs) to detect remote homologs with greater sensitivity using probabilistic models derived from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) [9] [10]. Despite their widespread adoption and utility, these traditional methods face significant limitations, particularly when sequence similarity drops into the "twilight zone" below 20-35% sequence identity, a common scenario with rapidly evolving viral proteins and genetically compact viral genomes [11] [12]. This application note details these limitations, provides quantitative comparisons, and outlines modern experimental protocols designed to overcome these challenges, specifically within the context of viral gene annotation and protein function analysis.

Key Limitations of Traditional Methods

Sensitivity in the "Twilight Zone" of Remote Homology

The most significant challenge for traditional methods is their rapidly declining sensitivity in the "twilight zone" of sequence similarity.

- Fundamental Performance Gap: Pairwise comparison methods like BLAST struggle to detect homologs when sequence identity falls below 30%. It is established that pairwise comparisons detect only about half of the true homologous relationships when sequence identity is between 20–30% [13]. This is because these methods rely on substitution matrices that cannot adequately capture complex evolutionary patterns at deep evolutionary distances.

- Advantage of Profile-Based Methods: Profile-based methods like HMMER constitute a significant advancement, as they can detect up to three times more homologs than pairwise methods in this low-similarity regime by aggregating information from multiple related sequences into a consensus model [13]. However, even profile HMMs have limits. Their sensitivity is highly dependent on the quality and breadth of the underlying MSA, and they often miss distantly related sequences that fall below alignment significance thresholds, particularly those with large insertions, deletions, or structural rearrangements [14] [13].

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

The exponential growth of sequence databases, such as those containing billions of metagenomic sequences, has placed immense strain on traditional alignment algorithms [11] [15].

- Algorithmic Complexity: Traditional alignment algorithms, such as Smith-Waterman for local alignment, have calculations that grow quadratically with the number of input residues, making them excessively time-consuming for searching large databases [12].

- Speed Comparison of Modern Tools: Next-generation, alignment-free methods have emerged that dramatically outpace traditional tools. The table below illustrates the substantial speed advantage of these new methods.

Table 1: Computational Speed Comparison of Homology Search Methods

| Method | Type | Relative Search Speed | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST | Pairwise Alignment | 1x (Baseline) | Heuristic-based local alignment [12] |

| HMMER | Profile HMM | ~100x faster than pre-v3.0 versions [9] | Probabilistic model-based search [10] |

| JackHMMER | Iterative Profile HMM | ~28,700x slower than DHR [15] | Iterative search for increased sensitivity [15] [14] |

| DHR | Embedding / Alignment-free | 22x faster than PSI-BLAST; 28,700x faster than JackHMMER [15] | Uses protein language model embeddings [15] |

| Protriever | Differentiable Retrieval | 100x faster than MMseqs2-GPU; 500,000x faster than JackHMMER [14] | End-to-end learned retrieval [14] |

Dependence on Prior Knowledge and Database Quality

The performance of BLAST and HMMER is intrinsically linked to the completeness and quality of existing sequence databases.

- Circular Dependency: These methods identify new sequences by their similarity to known sequences. This creates a fundamental limitation for discovering novel viral genes or protein families with no close representatives in existing databases, as there is nothing for the query sequence to match against [16].

- Bias in Reference Databases: Databases are often skewed toward well-studied organisms and protein families. This undersampling of viral diversity means that profile HMMs for viral detection can be highly biased, with low representation for many families, leading to false negatives when analyzing metagenomic samples from under-explored environments [13].

Challenges with Specific Biological Scenarios

Traditional methods have specific weaknesses when confronted with certain biological realities of proteins and viruses.

- Short Sequences and Peptides: Methods like HMMER struggle with short sequences, such as small proteins and peptides encoded in microbial genomes, which offer limited information for constructing statistically significant alignments [9].

- Intrinsically Disordered Regions: Viral proteins often contain intrinsically disordered regions that are not well-conserved at the sequence level. MSA-based retrieval frequently fails to detect meaningful homologies in these regions [14].

- Structural Homology Not Captured by Sequence: Protein structure is more conserved than sequence over evolutionary time. Sequences with low similarity can fold into nearly identical structures and perform related functions, a relationship that sequence-based methods like BLAST and HMMER are inherently unable to capture directly [11].

Emerging Solutions and Experimental Protocols

To address the limitations of traditional methods, the field is rapidly adopting approaches based on protein language models (pLMs) and advanced deep learning.

Protein Language Models (pLMs) for Remote Homology

Principle: pLMs, such as ESM and ProtTrans, are transformer-based models trained on millions of protein sequences using self-supervised learning. They learn the "language of life" by capturing complex evolutionary, physicochemical, and structural patterns, which are encoded into high-dimensional vector representations known as embeddings [11] [12].

Key Workflow: Embedding-based methods generally follow a two-stage process: converting sequences into embeddings and then comparing these embeddings.

Diagram 1: pLM embedding-based homolog detection workflow.

Protocol 1: Embedding-Based Homology Detection with Refinement

This protocol is adapted from recent studies that use pLM embeddings refined with clustering and double dynamic programming (DDP) for superior remote homology detection, particularly in the twilight zone [11].

Generate Embeddings:

- Input: Protein sequence(s) in FASTA format.

- Tool: Use a pretrained pLM like ProtT5, ESM-1b, or ProstT5 (which incorporates structural information).

- Action: Process the sequence to obtain a 2D matrix of residue-level embeddings (e.g., 1024 dimensions per residue for ProtT5).

Construct Similarity Matrix:

- For two sequences P and Q, compute a residue-residue similarity matrix ( SM ) where each entry ( SM{a,b} = \exp(-\delta(pa, qb)) ). Here, ( pa ) and ( q_b ) are the embeddings for residues a and b, and ( \delta ) is the Euclidean distance [11].

Normalize and Refine Matrix:

- Apply Z-score normalization to the similarity matrix row-wise and column-wise to reduce noise.

- Refine the normalized matrix using K-means clustering and Double Dynamic Programming (DDP). The clustering step helps identify structurally relevant regions, while DDP is used to find an optimal alignment path through the refined matrix, significantly improving alignment accuracy for remote homologs [11].

Validation:

- Benchmark the performance on a dataset with known structural similarities (e.g., from PISCES [11]). Calculate the Spearman correlation between predicted alignment scores and true structural similarity scores (e.g., TM-scores from TM-align).

End-to-End Differentiable Retrieval

Principle: This approach, exemplified by Protriever, fully integrates the retrieval of homologous sequences with the downstream modeling task. Instead of using a fixed, task-agnostic algorithm like BLAST, it uses a learned retriever that is trained to identify which sequences in a database are most useful for the specific objective, such as function prediction [14].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Resources for Modern Homology Detection

| Item / Resource | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 Model | Protein Language Model | Generates context-aware embeddings from single sequences; basis for feature extraction [14] [16]. |

| ProtT5 Model | Protein Language Model | Alternative pLM for generating residue-level embeddings; used in alignment refinement studies [11]. |

| HMMER Suite | Software Package | Industry standard for profile HMM-based sequence search (e.g., hmmsearch, jackhmmer) and model building (hmmbuild) [10] [17]. |

| UniRef50 Database | Protein Sequence Database | Clustered sequence database used for training pLMs and as a target for large-scale homology searches [14]. |

| Pfam Database | Profile HMM Database | Curated collection of profile HMMs for protein family annotation; often used with HMMER for functional characterization [10] [17]. |

| TABAJARA | Software Tool | Rational design of profile HMMs from MSAs by identifying conserved and discriminative motifs; useful for creating sensitive viral detectors [13]. |

| Faiss Index | Software Library | Enables fast similarity search on dense vector embeddings (e.g., for Protriever or DHR) [14]. |

Protocol 2: Differentiable Retrieval for Protein Family Classification

This protocol outlines how a tool like Protriever can be applied to a specific classification task, such as identifying Cas proteins or viral polymerases [14] [16].

Setup and Model Loading:

- Install the Protriever framework and download its pre-trained retriever and reader models.

- Build or download a vector index (e.g., using Faiss) of a large protein sequence database (e.g., UniRef50) converted into embeddings by the Protriever retriever.

Query and Retrieval:

- Input: A query protein sequence (e.g., a novel Cas protein candidate).

- Action: The retriever model encodes the query into an embedding and performs a fast vector similarity search against the pre-built index to retrieve the top-k most relevant homologous sequences (e.g., k=50).

Conditional Prediction:

- The reader model (e.g., a PoET architecture) takes the query sequence and the set of retrieved homologs as input.

- The model is conditioned on these retrieved sequences to perform the specific task, such as classifying the query into a protein family or predicting its function.

Validation:

Diagram 2: Differentiable retrieval workflow for protein classification.

Traditional homology-based methods like BLAST and HMMER have been foundational for viral gene annotation but are fundamentally constrained by their sensitivity in the twilight zone, computational scalability, and dependence on existing knowledge. The integration of protein language models and end-to-end differentiable retrieval systems represents a paradigm shift, offering a dramatic increase in both sensitivity and speed. For researchers in virology and drug development, adopting these modern protocols is crucial for unlocking the secrets of rapidly evolving viral pathogens, discovering novel protein functions, and accelerating the development of countermeasures against emerging viral threats.

Viral genome annotation and protein function analysis are fundamental to understanding pathogenicity, developing therapeutics, and tracking viral evolution. However, researchers face three persistent and interconnected obstacles that complicate these efforts: the characteristically high mutation rates of viruses, the prevalence of gene overlaps in their compact genomes, and the absence of universal functional markers across viral families. These challenges are particularly acute for RNA viruses, including major pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 and influenza, which pose significant threats to global health. This application note details these core challenges, presents quantitative data on their scale, provides actionable protocols to address them and visualizes the corresponding experimental strategies. It is intended to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with modern methodologies to enhance the accuracy of viral gene annotation and functional prediction, thereby accelerating research in virology and antiviral drug discovery.

Quantitative Profiling of Key Obstacles

The table below summarizes the core challenges in viral research, presenting key metrics and their direct impacts on research and public health.

Table 1: Core Obstacles in Viral Gene Annotation and Protein Function Analysis

| Obstacle | Quantitative Measure | Impact on Research & Public Health |

|---|---|---|

| High Mutation Rates | SARS-CoV-2: ~1.5 × 10⁻⁶ mutations per nucleotide per viral passage [18]. RNA viruses: 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻⁴ substitutions per nucleotide per cell infection (s/n/c) [19]. | Rapid emergence of vaccine- and treatment-evading variants [18]; necessitates continuous surveillance and updated diagnostics [19]. |

| Gene Overlaps | Pangenome analysis revealed 1,852 complex structural variants (SVs) and fully resolved intricate loci like SMN1/SMN2 and AMY1/AMY2 in human genomes, illustrating the challenge of parsing overlapping coding regions [20]. | Complicates genome annotation and functional mapping; even small mutations can disrupt multiple proteins, confounding variant effect prediction [20]. |

| Lack of Universal Markers | <1% of all known protein sequences have experimentally verified Gene Ontology (GO) annotations [21]. Viral proteomes are particularly underrepresented in functional databases. | Renders homology-based annotation methods ineffective; impedes computational prediction of protein function for novel or poorly characterized viral proteins [21]. |

Experimental Protocols to Address Key Challenges

Protocol 1: Profiling Viral Mutation Rates and Spectra Using CirSeq

Application Note: This protocol uses Circular RNA Consensus Sequencing (CirSeq) to measure the in vitro mutation rate and spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 with ultra-high accuracy, providing insight into viral evolution and fitness [18].

I. Cell Culture and Viral Passage

- Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Maintain VeroE6 cells (or other permissive lines like Calu-3 or primary Human Nasal Epithelial Cells (HNEC)) in standard culture conditions.

- Viral Inoculation: Infect cell monolayers at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI = 0.1) to minimize co-infection and complementation effects.

- Serial Passage: Harvest the virus supernatant after observing significant cytopathic effect (CPE). Use this to infect fresh cell monolayers for subsequent passages. Repeat for a minimum of seven passages to track mutation accumulation.

- Sample Collection: Collect viral RNA from the supernatant of each passage for sequencing.

- Procedure:

II. Circular RNA Consensus Sequencing (CirSeq)

- Procedure:

- RNA Fragmentation and Circularization: Fragment purified viral RNA and circulate the fragments using T4 RNA ligase.

- cDNA Synthesis and Amplification: Generate long cDNA molecules containing tandem repeats of the original RNA template via rolling-circle reverse transcription.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the cDNA and sequence using a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Consensus Calling: Computationally generate consensus sequences from the tandem repeats to eliminate sequencing and reverse-transcription errors, creating an ultra-high-fidelity dataset.

- Procedure:

III. Data Analysis

- Procedure:

- Mutation Identification: Map consensus reads to a reference genome (e.g., USA-WA1/2020 for SARS-CoV-2) and call variants.

- Mutation Rate Calculation: Calculate the mutation rate using lethal or highly detrimental mutations (e.g., premature stop codons in essential genes like RdRP), as their frequency equals the mutation rate.

- Spectrum and Context Analysis: Determine the mutation spectrum (e.g., dominance of C→U transitions) and analyze sequence context (e.g., 5'-UCG-3' for SARS-CoV-2) [18].

- Procedure:

Diagram 1: CirSeq mutation profiling workflow.

Protocol 2: Resolving Complex and Overlapping Genomic Regions

Application Note: This protocol leverages long-read sequencing and advanced assembly algorithms to generate high-quality, haplotype-resolved genomes, enabling the resolution of complex structural variants and overlapping gene regions [20].

I. Sample Preparation and Multi-platform Sequencing

- Procedure:

- DNA Extraction: Obtain high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the target sample.

- Long-Read Sequencing: Generate ~47x coverage of PacBio HiFi reads and ~56x coverage of Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) ultra-long reads.

- Phasing Data Generation: Perform complementary sequencing for phasing, such as Strand-seq or Hi-C, to obtain long-range haplotype information.

- Procedure:

II. De Novo Haplotype-Resolved Assembly

- Procedure:

- Graph-based Assembly: Assemble the sequenced reads into a phased assembly graph using a pipeline like Verkko, which integrates HiFi, ultra-long, and phasing data.

- Phasing: Use a tool like Graphasing with Strand-seq data to globally phase the assembly graph, achieving trio-quality phasing without parental data.

- Scaffolding and Gap Closing: Use the ultra-long reads to scaffold contigs and close gaps, aiming for telomere-to-telomere (T2T) status for chromosomes.

- Procedure:

III. Variant Calling and Annotation in Complex Regions

- Procedure:

- Variant Calling: Call structural variants (SVs), indels, and SNVs against a complete reference (e.g., T2T-CHM13) using multiple callers (e.g., PAV).

- Integration and Filtering: Create a high-confidence union callset by integrating orthogonal calls and filtering for support.

- Functional Annotation: Annotate variants, particularly those within resolved complex loci (e.g., MHC, SMN1/SMN2), to determine their impact on overlapping reading frames and regulatory elements.

- Procedure:

Diagram 2: Resolving complex genomic regions.

Protocol 3: Deep Learning-Based Protein Function Prediction

Application Note: This protocol applies the DPFunc deep learning model to predict protein function directly from sequence and predicted structure, bypassing the need for universal markers or homology [21].

I. Input Data Preparation

- Procedure:

- Protein Sequence: Obtain the amino acid sequence of the viral protein of interest.

- Structure Prediction: Generate a high-accuracy 3D protein structure from the sequence using AlphaFold2 or ESMFold if an experimental structure is unavailable.

- Domain Detection: Scan the protein sequence using InterProScan to identify functional domains.

- Procedure:

II. Feature Extraction with DPFunc

- Procedure:

- Residue-Level Feature Learning: Input the sequence into a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ESM-1b) to generate initial residue embeddings.

- Structure Feature Propagation: Construct a protein contact map from the 3D structure and update residue-level features using Graph Neural Networks (GCNs) to propagate information through the structural graph.

- Domain-Guided Attention: Convert identified domains into dense embeddings. Use a transformer-based attention mechanism to weigh the importance of different residues under the guidance of domain information, generating a protein-level feature vector.

- Procedure:

III. Function Prediction and Post-Processing

- Procedure:

- Function Annotation: Pass the protein-level features through fully connected layers to predict Gene Ontology (GO) terms for Molecular Function (MF), Cellular Component (CC), and Biological Process (BP).

- Logical Consistency: Apply a post-processing procedure to ensure predicted GO terms are consistent with the hierarchical structure of the GO database.

- Validation: Manually inspect key residues or regions highlighted by the model's attention mechanism for potential functional relevance.

- Procedure:

Diagram 3: DPFunc protein function prediction workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Viral Genomics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VeroE6 Cells | A permissive cell line for in vitro culture of a wide range of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. | Allows efficient viral replication and accumulation of mutations for evolutionary studies [18]. |

| PacBio HiFi & ONT Ultra-Long Reads | Long-read sequencing technologies for generating highly accurate or extremely long sequences, respectively. | Essential for resolving repetitive regions, complex structural variants, and haplotype phasing [20]. |

| Strand-seq / Hi-C Kits | Library preparation kits for sequencing technologies that preserve chromosomal contact or strand orientation information. | Provides long-range phasing information crucial for building haplotype-resolved assemblies [20]. |

| T4 RNA Ligase | Enzyme used to circularize RNA fragments in the CirSeq protocol. | Critical step for creating templates for rolling-circle amplification to achieve ultra-low error sequencing [18]. |

| InterProScan Software | A tool that scans protein sequences against signatures from numerous databases to identify domains and functional sites. | Provides the essential domain information that guides the DPFunc model to focus on functionally relevant regions [21]. |

| AlphaFold2/ESMFold | Deep learning systems for predicting protein 3D structures from amino acid sequences with high accuracy. | Generates reliable structural inputs for methods like DPFunc when experimental structures are unavailable [21]. |

| DPFunc Model | A deep learning-based tool for predicting protein function using domain-guided structure information. | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods, offering interpretable predictions and identifying key functional residues [21]. |

The Critical Impact of Accurate Annotation on Understanding Viral Pathogenesis and Ecology

The accurate annotation of viral genomes—the precise identification and functional characterization of genes and proteins—is a cornerstone of modern virology. It provides the foundational map that guides research into how viruses cause disease (pathogenesis), interact with their environments (ecology), and evolve. Inaccurate or incomplete annotation can obscure critical viral functions, leading to a flawed understanding of viral mechanisms and hampering the development of effective countermeasures such as antivirals and vaccines. The deployment of advanced computational tools has dramatically improved our capacity to decode viral genomes, revealing not only standard viral genes but also auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) that viruses use to reprogram host metabolism during infection [22]. The integration of machine learning and homology-based methods now allows for the high-resolution analysis of viral communities from metagenomic data, offering unprecedented insights into their role in health, disease, and global ecosystems [22].

Key Annotation Tools and Methodologies

Automated Viral Identification and Annotation Tools

Several sophisticated bioinformatics tools have been developed to automate the recovery and annotation of viral sequences from complex genomic and metagenomic data. These tools employ diverse strategies, from hybrid machine learning to specialized neural networks, to maximize the identification of both lytic and integrated proviruses.

Table 1: Key Tools for Viral Genome Identification and Annotation

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | Key Features and Capabilities | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIBRANT [22] | Hybrid machine learning and protein similarity using HMMs. | - Recovers viruses from metagenomic assemblies- Identifies integrated proviruses- Annotates AMGs and metabolic pathways- Determines genome quality | Average recovery of 94% of viruses from metagenomic sequences; superior performance in reducing false positives. |

| Vgas [23] | Combination of ab initio method and similarity-based (BLASTp) approach. | - Automated viral gene finding- Functional annotation module- Improved handling of overlapping genes | Highest average precision and recall on RefSeq viruses; 6% higher precision for small genomes (≤10 kb). |

| GeneMarkS [24] | Self-training algorithm for gene prediction using statistical models. | - Genome-specific model training- Identifies missing or divergent genes- Useful for novel gene discovery | Enabled refinement of RefSeq genome annotations; identified hundreds of new genes in well-studied viruses. |

| VirSorter [22] | Database searches of predicted proteins and sequence signatures. | - Identifies viral scaffolds and integrated proviruses- Uses virus-specific databases and Pfam | Benchmark tool; performance surpassed by newer methods like VIBRANT. |

Protocols for Viral Genome Annotation

The following protocols outline standard and advanced workflows for annotating viral genomes, from a basic homology-based approach to a more comprehensive metagenome-informed pipeline.

Protocol 1: Standard Gene Annotation for a Complete Viral Genome

This protocol is designed for annotating a single, complete viral genome sequence, such as one derived from an isolate.

Gene Prediction: Use a specialized gene-finding tool to identify all potential open reading frames (ORFs) or genes within the genome sequence.

Functional Annotation: Perform homology searches for each predicted protein sequence against reference databases.

Annotation of Auxiliary Metabolic Genes (AMGs): Identify host-derived metabolic genes that may provide the virus with a fitness advantage.

- Method: Cross-reference annotated genes with known metabolic pathway databases (e.g., KEGG, MetaCyT) to highlight AMGs involved in processes like nutrient cycling [22].

Annotation Curation and Finalization: Manually review and refine the automated annotations.

- Actions: Check for consistent start codons, resolve overlapping genes, and add evidence-based functional notes. The final annotations should be stored in a standardized format (e.g., GenBank format).

Protocol 2: Viral Community Annotation from Metagenomic Assemblies

This protocol leverages tools like VIBRANT for the large-scale identification and functional characterization of viruses from mixed microbial community sequencing.

Input Data Preparation: Assemble metagenomic sequencing reads into longer sequences (scaffolds/contigs) using an assembler like MEGAHIT or metaSPAdes.

Viral Sequence Identification: Run the assembled scaffolds through VIBRANT to distinguish viral from non-viral sequences.

- Process: VIBRANT uses a neural network of protein annotation signatures and a v-score metric to classify sequences, maximizing the recovery of diverse and novel viruses [22].

Genome Quality Assessment: Determine the completeness and quality of the identified viral genomes.

- Process: VIBRANT automatically evaluates and reports on genome quality, filtering out partial genome fragments to reduce false positives [22].

Functional and Metabolic Profiling: Characterize the functional potential of the viral community.

- Process: VIBRANT annotates proteins and highlights AMGs, providing a profile of the metabolic pathways present in the viral community [22]. This output is crucial for evaluating the functional role of viromes in different environments.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive annotation process for viral genomes, from sequence input to functional and ecological analysis:

Impact on Viral Pathogenesis Research

Precise annotation is instrumental in uncovering the molecular mechanisms by which viruses cause disease. By correctly identifying virulence factors and other pathogenicity-related genes, researchers can develop targeted therapeutic strategies.

Discovery of Novel Virulence Factors: Automated annotation pipelines have successfully identified previously overlooked genes in well-studied viral genomes. For instance, a re-annotation of the Epstein-Barr virus genome using GeneMarkS revealed a new gene encoding a protein similar to the alpha-herpesvirus minor tegument protein UL14, which has heat shock functions [24]. Similarly, a gene predicted in Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 was shown to encode a BALF1-like protein involved in apoptosis regulation and potential carcinogenesis [24]. These findings open new avenues for understanding viral persistence and oncogenesis.

Linking Viral Communities to Disease States: Advanced annotation tools enable the comparison of viromes between healthy and diseased individuals. In a study of Crohn's disease, the VIBRANT tool was used to identify specific viral groups, notably Enterobacteriales-like viruses, that were more abundant in patients compared to healthy controls [22]. Furthermore, the annotation revealed putative dysbiosis-associated viral proteins, providing a potential viral link to the maintenance of the diseased state [22].

Tracking Pathogen Evolution during Outbreaks: During the 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic in Western Africa, genomic sequencing and annotation of viral isolates in near real-time allowed researchers to track the accumulation of mutations, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and intrahost variants (iSNVs) [25]. Accurate annotation of these variants—classifying them as nonsense, missense, or intergenic—is critical for investigating whether any changes correlate with altered transmission dynamics or disease severity, informing public health responses [25].

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Genes Discovered Through Improved Annotation

| Virus | Newly Annotated Gene / Function | Biological Significance | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epstein-Barr Virus [24] | Protein similar to UL14 tegument protein (heat shock function) | Viral assembly, morphogenesis, and host interaction. | Computational similarity (e.g., PSI-BLAST) after improved gene prediction. |

| Alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 [24] | BALF1-like protein | Regulation of apoptosis; potential role in carcinogenesis. | Computational similarity (e.g., PSI-BLAST) after improved gene prediction. |

| Crohn's Disease Virome [22] | Enterobacteriales-like viruses; dysbiosis-associated proteins | Potential maintenance of inflammatory disease state. | Metagenomic sequencing and annotation with VIBRANT. |

Impact on Viral Ecology Research

In natural environments, viruses are key players in microbial ecology. Accurate annotation is vital for understanding their diverse roles in ecosystem dynamics, from driving nutrient cycling to shaping microbial community structure.

Revealing Auxiliary Metabolic Genes (AMGs): A significant contribution of viral annotation to ecology is the systematic discovery of AMGs. These are host-derived metabolic genes that are captured by viruses and expressed during infection to reprogram host cell machinery for more efficient viral replication. VIBRANT and similar tools automatically highlight AMGs, enabling researchers to determine that viruses can directly manipulate major biogeochemical cycles, including those of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur [22]. For example, the identification of viral AMGs involved in photosynthesis or central carbon metabolism in oceanic viruses reveals a direct viral role in regulating primary production [22].

Elucidating Recombination and Evolution: Viral recombination is a powerful evolutionary force that can generate new viral variants with altered host range or environmental adaptability. Annotation of recombinant viral genomes, such as the "Crucivirus" apparently derived from recombination between a DNA and RNA virus, provides insights into the origins and potential hosts of novel viral groups [26]. Accurate annotation of the boundaries between recombined modules is essential for these studies.

Characterizing Diverse Viral Communities: Metagenomic sequencing of environmental samples (e.g., oceans, soil, humans) yields a vast array of unknown viral sequences. Tools like VIBRANT, which are not reliant on sequence features from known viruses, allow for the annotation of this "viral dark matter." This capability is crucial for assessing the functional potential of entire viral communities and their collective impact on the ecology of their respective environments [22].

The following diagram illustrates how viral AMGs directly influence host metabolism and broader ecosystem-level processes:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Annotation and Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Protein Databases | Provide curated sequences for homology-based functional annotation of predicted viral proteins. | RefSeq, SwissProt [23] [24] |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) Databases | Used for non-reference-based, probabilistic protein annotation and identifying distant homologies. | Pfam; VIBRANT's custom HMMs [22] |

| Metabolic Pathway Databases | Contextualize annotated viral genes, especially AMGs, into broader biochemical pathways. | KEGG, MetaCyT [22] |

| Virus-Specific Primer Sets | Enable targeted amplification of viral sequences via RT-PCR for Sanger sequencing in outbreak settings. | Designed from known viral sequences [25] |

| Sequence-Independent Primer Kits | Allow for unbiased amplification and deep sequencing of viral samples, crucial for novel pathogen discovery. | Used in high-throughput sequencing protocols [25] |

| RNase H-based Digestion Kits | Selectively degrade contaminating host RNA (e.g., ribosomal RNA) to enrich viral content in sequencing libraries. | Used for sample preparation from complex clinical or environmental samples [25] |

| Variant Calling Software | Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and intrahost variants (iSNVs) from sequencing data. | GATK, Samtools [25] |

Next-Generation Annotation Toolkit: From AI Models to Automated Pipelines

Leveraging Protein Language Models (PLMs) for Remote Homology Detection

Remote homology detection, the identification of evolutionary relationships between proteins with highly divergent sequences, represents a significant challenge in computational biology. This challenge is particularly acute in viral genomics, where high mutation rates and vast sequence diversity often render traditional sequence-based methods ineffective. Protein Language Models (PLMs), trained on millions of protein sequences, have emerged as powerful tools that learn fundamental principles of protein structure and function, enabling them to detect these distant evolutionary relationships with unprecedented accuracy. This Application Note details the operational principles, performance benchmarks, and standardized protocols for implementing PLM-based remote homology detection, with a specific focus on applications in viral gene annotation and protein function analysis to support research and drug development.

The annotation of viral proteins currently relies heavily on sequence homology methods using tools like BLAST and profile Hidden Markov Models (pHMMs). These methods struggle with remote homology detection because viral sequences evolve rapidly, often diverging beyond recognition by traditional sequence-based metrics while maintaining similar structures and functions [27] [6]. Protein Language Models (PLMs), inspired by breakthroughs in natural language processing, address this limitation by learning high-dimensional representations (embeddings) of protein sequences that capture structural and functional properties beyond mere sequence similarity [28].

PLMs are trained on billions of protein sequences through self-supervised tasks, such as masked amino acid prediction, learning the "grammar" and "syntax" of protein sequences. This enables them to generate embeddings that encapsulate evolutionary, structural, and functional information [28] [29]. For viral protein annotation, this capability is transformative—studies have shown that PLM-based approaches can expand the annotated fraction of ocean virome viral protein sequences by 37% compared to traditional methods, uncovering novel protein families such as a previously unidentified DNA editing protein family in marine picocyanobacteria [27].

Performance Comparison of PLM-Based Methods

Various PLM-based approaches have been developed for remote homology detection, each with distinct methodologies and performance characteristics. The table below summarizes key quantitative benchmarks for major tools.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of PLM-Based Remote Homology Detection Tools

| Tool Name | Core Methodology | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLMSearch [30] | Uses deep representations from pre-trained PLM; trained on real structure similarity (TM-score) | → 3x more sensitive than MMseqs2→ Comparable to state-of-art structure search→ Searches millions of pairs in seconds→ AUROC: Family-level (0.928), Superfamily-level (0.826) | Speed of sequence search with sensitivity of structure search |

| TM-Vec [31] | Twin neural network predicting TM-scores from sequence; creates searchable vector database | → Strong correlation (r=0.97) with TM-align scores→ Accurate even at <0.1% sequence identity (median error=0.026)→ Enables sublinear search time (O(log₂n)) | Scalable structural similarity search in large databases |

| VPF-PLM [27] | Feed-forward neural network on PLM embeddings for viral protein classification | → AUROC of 0.90 across PHROGs functional categories→ Correctly re-annotated 66.6% (38/57) of misannotated PHROGs families | Specialized for viral protein function prediction |

| Soft-Alignment [6] | Embedding-based alignment using amino acid-level similarity without substitution matrices | → Identifies remote homologs missed by blastp and pooling methods→ Provides BLAST-like interpretable alignments | Superior interpretability with alignment visualization |

| PLM-Interact [32] | Jointly encodes protein pairs using modified ESM-2 architecture | → State-of-art performance in cross-species PPI prediction→ AUPR improvements of 2-28% over other methods | Extends PLMs to predict protein-protein interactions |

Table 2: Comparison of PLM Architectures and Training Databases

| PLM Model | Architecture | Training Database | Noted Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 [32] [33] | Transformer | UniRef | Strong performance on structure-related tasks; widely adapted |

| ProtT5 [34] | Transformer | BFD (Big Fantastic Database) | High-quality sequence embeddings |

| Transformer_BFD [27] | Transformer | BFD (2.1 billion sequences) | Best performance for viral protein classification |

| CARP [34] | CNN | Various | Alternative architecture, lower performance than transformers |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Remote Homology Detection with PLMSearch

Purpose: To identify remote homologous proteins for a query sequence using PLMSearch [30].

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation

- Obtain query protein sequence(s) in FASTA format.

- Prepare target database (e.g., Swiss-Prot, UniRef50) in PLMSearch-compatible format.

Embedding Generation

- Process the query sequence through a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ESM) to generate deep representations.

- Technical Note: PLMSearch uses embeddings that capture structural information, enabling detection of homology beyond sequence similarity.

Domain Filtering with PfamClan

- Apply PfamClan to filter protein pairs that share the same Pfam clan domain.

- Purpose: This step reduces search space by quickly eliminating unrelated sequences.

Structural Similarity Prediction

- For pre-filtered pairs, use the SS-predictor (Structural Similarity predictor) to predict TM-scores.

- Key Innovation: The SS-predictor is trained on real structure similarity data, allowing it to infer structural similarity without 3D structures.

Ranking and Output

- Sort pre-filtered pairs based on predicted similarity scores.

- Output ranked list of potential homologs for the query.

Alignment Generation (Optional)

- For top-ranked hits, use PLMAlign to generate detailed sequence alignments and alignment scores.

- Application: Provides interpretable results for downstream analysis.

Validation: On SCOPe40-test dataset, PLMSearch achieved AUROC of 0.928 at family-level and 0.826 at superfamily-level, significantly outperforming MMseqs2 [30].

Protocol 2: Viral Protein Family Classification with VPF-PLM

Purpose: To classify viral proteins into functional categories using PLM embeddings [27].

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Collection

- Curate training data from annotated viral protein families (e.g., PHROGs database containing 868,340 sequences across 38,880 families).

Embedding Generation

- Generate protein sequence embeddings using Transformer_BFD model, trained on 2.1 billion protein sequences.

- Rationale: This model showed best performance for viral protein classification tasks.

Classifier Training

- Train a feed-forward neural network classifier using viral protein embeddings as input.

- Implement five-fold cross-validation to assess performance.

- Performance Target: Achieve AUROC >0.90 across functional categories.

Classification of Novel Sequences

- Process uncharacterized viral protein sequences through the trained classifier.

- Obtain probability scores across nine functional categories: transcription regulation, integration and excision, etc.

Validation and Interpretation

- Validate predictions against known families and experimental data.

- Result Interpretation: The classifier successfully re-annotated 66.6% of misannotated PHROGs families during validation.

Application: This approach expanded annotations of viral proteins from the global ocean virome by 37%, enabling discovery of novel viral functions [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PLM-Based Remote Homology Detection

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLMSearch | Software Tool | Remote homology search using sequence input only | https://dmiip.sjtu.edu.cn/PLMSearch [30] |

| PHROGs Database | Database | Curated library of viral protein families with functional annotations | https://github.com/kellylab/viralproteinfunction_plm [27] |

| ESM-2 Model | Pre-trained PLM | Protein language model for generating sequence embeddings | Available through Hugging Face Transformers [32] |

| TM-Vec | Software Tool | Predicts TM-scores between protein sequences for structural similarity | Code available on GitHub [31] |

| UniProt/Swiss-Prot | Database | Curated protein sequence database for target searches | https://www.uniprot.org/ [30] |

Implementation Considerations

Model Selection Guidelines

Research indicates that PLMs with transformer architectures trained on larger, more diverse databases (e.g., BFD with 2.1 billion sequences) generally outperform alternatives for remote homology detection [27] [34]. For viral protein annotation specifically, domain-adapted models like those further pre-trained on viral sequences show enhanced performance. The structure-informed training approach, which integrates remote homology detection during training without requiring explicit structures as input, has demonstrated consistent improvements in function annotation accuracy for EC number and GO term prediction [29].

Computational Requirements

PLM-based methods exhibit varying computational demands:

- PLMSearch offers efficiency comparable to MMseqs2, searching millions of query-target pairs in seconds on CPU-based servers [30].

- TM-Vec enables efficient structural similarity searches with sublinear scaling (O(log₂n)) through vector database indexing [31].

- For large-scale applications, GPU acceleration significantly reduces inference time for embedding generation.

Protein Language Models represent a paradigm shift in remote homology detection, particularly for challenging domains like viral genomics. By capturing structural and functional properties from sequence data alone, PLM-based approaches including PLMSearch, TM-Vec, and specialized viral protein classifiers enable researchers to detect evolutionary relationships that were previously undetectable with traditional methods. The protocols and benchmarks provided in this Application Note offer researchers practical pathways to implement these powerful tools, potentially accelerating discovery in viral genomics, functional annotation, and drug target identification.

Viral genome annotation is a critical first step in understanding pathogenicity, transmission dynamics, and therapeutic vulnerabilities of viruses. The exponential growth of viral sequencing data has created an urgent need for robust, automated annotation pipelines that ensure consistency, accuracy, and compliance with database submission requirements. This review examines four specialized bioinformatics tools—VADR, VAPiD, VIRify, and Vgas—that address the challenges of viral genome annotation in the era of high-throughput sequencing. These tools represent different methodological approaches to a common problem: extracting biologically meaningful information from raw viral sequences while accommodating the unique complexities of viral genomics, including ribosomal slippage, RNA editing, overlapping reading frames, and diverse genome architectures. The accurate annotation of viral genomes enables researchers to identify potential drug targets, understand immune evasion mechanisms, and track the evolution of viral proteins in response to selective pressures.

Key Characteristics and Methodologies

VADR (Viral Annotation DefineR), developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), employs a reference-based validation approach using profile hidden Markov models (HMMs) and covariance models [35] [36]. It focuses on classification and quality control of viral sequences, particularly for Norovirus, Dengue, and SARS-CoV-2, ensuring they meet GenBank submission standards [37]. The pipeline outputs detailed reports specifying sequences that pass or fail validation along with specific alerts for problematic annotations [36] [37].

VAPiD (Viral Annotation Pipeline and iDentification) distinguishes itself as a lightweight, portable tool designed specifically to facilitate GenBank deposition [38] [39]. It uses a reference-based alignment strategy with MAFFT, followed by annotation transfer from the best-matching reference genome [38]. This Python-based tool handles complex viral features including ribosomal slippage and RNA editing through specialized code for specific viruses like human parainfluenza viruses and Ebola virus [38].

Vgas (Viral Genome Annotation System) implements a hybrid methodology combining ab initio gene prediction with similarity-based approaches [40]. This dual strategy allows it to identify novel genes without complete reliance on existing databases while providing functional annotations through BLASTp alignment against reference sequences [40]. Testing on 5,705 RefSeq genomes demonstrated superior performance particularly for small viral genomes (≤10 kb) [40].

VIRify is a comprehensive annotation platform developed for use within the European Virus Bioinformatics Center (EVBC) framework. Although not detailed in the provided search results, it represents a more recent development in the viral annotation landscape, designed to handle diverse viral families through a unified pipeline.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Viral Annotation Pipelines

| Feature | VADR | VAPiD | Vgas | VIRify |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Approach | Reference-based validation | Reference-based alignment | Hybrid: ab initio + similarity-based | Comprehensive automated annotation |

| Key Strength | Quality control for submissions | GenBank submission readiness | Novel gene discovery | Broad taxonomic range |

| Supported Viruses | Norovirus, Dengue, SARS-CoV-2 [36] | HIV, HPV, RSV, Coronaviruses, Hepatitis A-E [38] [39] | Broad range (tested on 5,705 genomes) [40] | Diverse viral families |

| GenBank Submission | Direct validation for submission [37] | Direct preparation of submission files [38] | Not specialized for submission | Not specified |

| Installation | Complex model setup | Lightweight, cross-platform [39] | Conda install available [41] | Containerized |

| Dependencies | HMMER, Infernal, BLAST+ | Python, MAFFT, BLAST+, tbl2asn [39] | BLAST+ | Custom dependencies |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Annotation Pipelines

| Pipeline | Annotation Accuracy | Speed | Ease of Use | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VADR | High for supported viruses [35] | Moderate | Intermediate | Model-based validation [35] |

| VAPiD | High for non-segmented viruses [38] | Fast | User-friendly | Handles RNA editing [38] |

| Vgas | 1-6% higher precision than Prodigal/GeneMarkS [40] | Fast | Web interface available | Combined prediction method |

| VIRify | Not specified | Not specified | Web interface | Taxonomic classification |

Performance and Validation

Quantitative assessments demonstrate the relative strengths of these pipelines. In validation studies, VADR correctly annotated 96.3% of publicly available viral genomes and 98.1% of novel genomes not included in its training set [35]. The pipeline has proven effective at identifying complex biological features including overlapping open reading frames, mature peptides, and transcriptional slippage events [35].

Vgas demonstrates competitive performance compared to established gene finders like Prodigal and GeneMarkS, achieving 1% higher precision and recall on general viral genomes and showing particularly strong performance on small viral genomes (≤10 kb) where it achieved 6% higher precision [40]. The developers note that collaborative prediction using multiple programs yields even better results than any single tool [40].

VAPiD has been validated on numerous human pathogens including human immunodeficiency virus, human parainfluenza viruses 1-4, human metapneumovirus, coronaviruses, hepatitis viruses, and others [38]. Its robustness stems from the reference-based alignment approach which effectively handles the diversity of viral sequences encountered in clinical and research settings.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

VADR Implementation Protocol

Objective: To annotate and validate viral genome sequences using VADR prior to GenBank submission.

Materials:

- Viral consensus sequence in FASTA format

- VADR software (installed locally or via container)

- Reference models for target viruses

Methodology:

- Software Setup: Install VADR following the official NCBI documentation, ensuring all dependencies (HMMER, Infernal, BLAST+) are properly configured.

- Model Selection: Identify appropriate reference models for your target virus. VADR includes pre-built models for common pathogens.

- Sequence Annotation: Execute the basic VADR command:

vadr -r <reference_model> -s <sequence.fasta> output_directory - Output Interpretation: Examine the

.sqaoutput file to identify sequences that passed or failed validation. Investigate any alerts in the.altfile. - Troubleshooting: For sequences failing validation, review specific error codes and consider whether they represent biological realities or sequencing artifacts.

Validation: VADR output files should be thoroughly reviewed before submission. The .sqa file contains pass/fail information, while the .alt file details specific annotation issues that require attention [37]. For SARS-CoV-2 genomes, ensure the sequence passes all critical checks to avoid rejection by GenBank.

VAPiD Annotation Protocol

Objective: To rapidly annotate viral genomes and prepare files for GenBank submission using VAPiD.

Materials:

- Viral sequences in FASTA format

- NCBI submission template (.sbt file)

- Sample metadata (optional CSV file)

- VAPiD software installation

Methodology:

- Preparation: Generate a submission template through the NCBI Submission Portal and compile viral sequences in a FASTA file with headers as strain names.

- Software Configuration: Ensure all dependencies (Python, Biopython, MAFFT, BLAST+, tbl2asn) are installed and accessible in the system PATH [39].

- Reference Database Setup: Download the pre-built viral database from the VAPiD releases page and place it in the VAPiD directory.

- Annotation Execution: Run VAPiD with the command:

python vapid.py input.fasta author.sbt --metadata_loc metadata.csv - Metadata Handling: If no metadata file is provided, VAPiD will interactively prompt for collection date, location, and coverage information.

- Output Processing: Locate the generated .sqn files in the output directories, which are ready for submission to GenBank via email.

Validation: Verify annotation quality by examining the generated .gbk files in a genome browser and checking that all required GenBank features (CDS, genes, mature peptides) are properly annotated.

Vgas Gene Prediction Protocol

Objective: To identify genes in viral genomes using Vgas's combined ab initio and similarity-based approach.

Materials:

- Viral genomic sequences in FASTA format

- Vgas installation (local or web interface)

- Reference protein databases (optional)

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Format viral sequences in FASTA format, ensuring they are complete or near-complete genomes for optimal prediction accuracy.

- Tool Execution: Access Vgas through the web interface at http://cefg.uestc.cn/vgas/ or run locally following installation instructions.

- Parameter Selection: Utilize default parameters for most viruses, or adjust for specific viral families based on known characteristics.

- Result Interpretation: Examine the output for predicted genes, including start/stop codons, functional annotations, and confidence scores.

- Comparative Analysis: For critical applications, compare Vgas predictions with other gene finders (Prodigal, GeneMarkS) as the developers note that collaborative prediction approaches yield superior results [40].

Validation: For known viruses, verify predictions against reference annotations in RefSeq. For novel viruses, validate predictions through conserved domain analysis and homology searching.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Databases | Provide validated sequences for comparison | GenBank, RefSeq, VADR models [35] |

| Alignment Tools | Map gene locations from references to query sequences | MAFFT (used in VAPiD) [38] |

| Sequence Homology Tools | Identify closest reference sequences | BLAST+ (used in VAPiD and Vgas) [38] [40] |

| Annotation Transfer Algorithms | Propagate annotations from references to new sequences | VAPiD's pairwise alignment approach [38] |

| Ab Initio Gene Finders | Predict genes without reference sequences | Vgas's integrated prediction module [40] |

| GenBank Submission Tools | Format annotations for database deposition | tbl2asn (used in VAPiD) [39] |

| Quality Control Modules | Validate annotation quality and completeness | VADR's alert system [37] |

Applications in Viral Research and Drug Development

The annotation pipelines discussed serve as foundational tools for multiple research applications with significant implications for therapeutic development. Accurate genome annotation enables researchers to identify essential viral proteins that serve as potential drug targets, map domains involved in host-pathogen interactions, and track evolutionary changes that may confer drug resistance.

In vaccine development, these tools facilitate the identification of conserved epitopes and structural proteins for inclusion in vaccine candidates. The VADR pipeline has been specifically employed for quality control of SARS-CoV-2 sequences submitted to public databases, ensuring data integrity for phylogenetic analyses that inform public health responses [37]. The detection of novel biological features, such as the first reported HCoV-OC43 NS2 knockout in a human infection identified through VADR, demonstrates how these tools can reveal previously unrecognized aspects of viral biology [35].

For drug development professionals, consistent annotation across viral strains enables comparative analyses that identify conserved functional domains essential for viral replication, which represent promising targets for broad-spectrum antiviral therapies. The ability of VAPiD to handle complex viral features like ribosomal slippage and RNA editing ensures that these non-canonical translation events, which can produce essential viral proteins, are properly annotated and considered in therapeutic design.

Specialized viral annotation pipelines represent essential resources for researchers and drug development professionals working with viral genomes. VADR excels in validation and quality control for database submissions, VAPiD provides a lightweight solution specifically designed for GenBank deposition, Vgas offers superior gene prediction capabilities through its hybrid approach, and VIRify presents a comprehensive solution for diverse viral taxa. The optimal pipeline selection depends on the specific research objectives, with VADR and VAPiD being particularly valuable for public health surveillance and data sharing, while Vgas offers advantages for novel virus characterization. As viral genomics continues to evolve, these tools will play an increasingly critical role in translating raw sequence data into biologically meaningful information that drives therapeutic discovery and public health interventions.

Integrating Ab Initio Gene Prediction with Similarity-Based Approaches

Accurate gene annotation is a cornerstone of genomic research, particularly in virology where it directly informs our understanding of pathogenicity and supports drug and vaccine development. Two predominant computational strategies have emerged: ab initio methods, which identify genes based on statistical patterns intrinsic to the genomic sequence, and similarity-based methods, which leverage homology to known genes or proteins. While powerful, each approach has limitations; ab initio methods can miss novel genes without standard features, and similarity-based methods struggle with rapidly evolving viral genes that lack close homologs. The integration of these methodologies creates a synergistic effect, significantly enhancing the accuracy and completeness of viral gene annotations, which is crucial for subsequent protein function analysis.

Key Integration Strategies and Performance

The integration of ab initio and similarity-based approaches can be implemented through several computational frameworks. The performance of these strategies has been quantitatively evaluated on standardized datasets, revealing significant improvements over single-method applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Integrated Gene Prediction Programs

| Program | Core Integration Strategy | Reported Improvement in Exon Prediction | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGPred [42] | Filters ab initio predictions with sequential BLASTX searches and an intron database. | 4-10% increase in exon-level performance. [42] | Eukaryotic genomes; useful for viral hosts. |

| GenomeScan [42] | Incorporates BLASTX similarity information directly into the Genscan probabilistic model. | ~10% increase in exon sensitivity over Genscan. [42] | General eukaryotic gene finding. |

| Projector [43] | Uses a pair-HMM to transfer annotations from a related genome, leveraging conserved exon-intron structure. | More accurate than Genewise for proteins <80% identical. [43] | Comparative annotation of related genomes. |

| VIRify [44] | Combines viral sequence detection with annotation via curated profile HMMs for taxonomic classification. | Average taxonomic classification accuracy of 86.6%. [44] | Prokaryotic and eukaryotic virus analysis in metagenomes. |

The challenge of gene prediction is underscored by benchmark studies. The G3PO benchmark, which includes complex genes from diverse eukaryotes, found that even state-of-the-art ab initio programs failed to predict 68% of exons with perfect accuracy when used alone, highlighting the necessity of integrating additional evidence like homology data [45].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: The EGPred Multi-Step BLAST Integration Pipeline

EGPred exemplifies a protocol that systematically combines similarity searches with ab initio signals to refine gene models [42].

1. Initial Similarity Search:

- Tool:

BLASTX - Database: RefSeq protein database.

- Parameters: E-value threshold < 1.

- Purpose: To identify high-confidence protein hits and approximate coding regions in the genomic query sequence.

2. Secondary, Relaxed Similarity Search:

- Tool:

BLASTX - Database: Hits from the first BLASTX run.

- Parameters: Relaxed E-value threshold < 10.

- Purpose: To retrieve all probable coding exon regions that may have been missed by the stringent first search.

3. Intron Region Detection:

- Tool:

BLASTN - Database: An intron database.

- Purpose: To identify probable intronic regions, which will help filter out spurious exons predicted in non-coding regions.

4. Exon Filtering and Splice Site Reassignment:

- Compare the probable intron and exon regions from the previous steps to filter out incorrect exons.

- Use the

NNSPLICEprogram to precisely reassign splicing signal site positions (donor and acceptor sites) at the termini of the remaining probable coding exons.

5. Combined Prediction:

- Run one or more ab initio gene predictors (e.g., Genscan, HMMgene) on the genomic sequence.

- Combine the exons derived from the similarity-based steps with the ab initio predictions. The final gene model is constructed based on the relative strength of start/stop codons and splice sites from both sources.

EGPred Workflow: A multi-step BLAST filtering and integration pipeline.

Protocol 2: Embedding-Based Annotation for Viral Proteins

For viral proteins, which often exhibit rapid evolution and low sequence similarity, a novel protocol using protein Language Model (pLM) embeddings has been developed to overcome the limitations of traditional homology searches [6].

1. Embedding Generation:

- Tool: A transformer-based protein Large Language Model (LLM) (e.g., ProtBERT, ESM).

- Input: Amino acid sequence of the query viral protein.

- Process: The model processes the sequence and generates a high-dimensional vector representation (embedding) for each amino acid residue, capturing contextual, functional, and structural information.

2. Database Search:

- Database: A pre-computed database of embeddings for proteins with known functions.

- Tool: A heuristic search algorithm (e.g., k-nearest neighbors) is used to identify the subject sequences in the database whose embeddings are most similar to the query embedding.

3. Soft Alignment and Function Inference:

- Perform a "soft alignment" between the query sequence and the top subject sequences from the database search. This algorithm uses the cosine similarity between amino acid embeddings instead of a traditional substitution matrix (e.g., BLOSUM) to find the optimal alignment.

- The function of the query protein is inferred from the function of the subject sequence(s) that achieve the highest soft alignment score, providing a traceable, BLAST-like alignment for interpretation.

Viral Protein Annotation: An embedding-based soft alignment workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Integrated Gene Prediction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Annotation |

|---|---|---|

| BLAST Suite [42] | Similarity Search | Finds regions of local similarity between nucleotide or protein sequences against databases. Essential for initial homology evidence. |

| HMMER [44] | Profile HMM Search | Uses hidden Markov models for more sensitive, profile-based sequence similarity searching, as used in VIRify. |

| Augustus [45] | Ab Initio Predictor | Predicts genes using a generalized hidden Markov model; can be trained for specific organisms. |

| Genscan [42] | Ab Initio Predictor | An early but influential HMM-based predictor of gene structure in vertebrate and Arabidopsis sequences. |

| NNSPLICE [42] | Signal Sensor | Predicts splice sites (donor and acceptor) in genomic DNA, crucial for defining exon-intron boundaries. |

| VIRify [44] | Integrated Pipeline | A comprehensive pipeline for detection, annotation, and taxonomic classification of viral sequences in metagenomic assemblies. |

| Protein LLMs (e.g., ESM) [6] | Embedding Generator | Generates contextual amino acid embeddings that capture structural and functional information for advanced annotation. |

| RefSeq Database [42] | Curated Database | A comprehensive, curated database of non-redundant sequences used for reliable similarity searches. |

Within viral genomics research, the transition from raw sequence data to a submission-ready, annotated GenBank file is a critical yet often complex process. This pathway bridges the gap between sequencing experiments and public data dissemination, enabling functional annotation of viral genes and subsequent analysis of protein functions crucial for understanding pathogenesis and identifying therapeutic targets. This protocol details a standardized workflow for researchers preparing viral genome annotations, with particular emphasis on the specific requirements of viral gene features and protein domain identification. The structured approach ensures that submitted data meets GenBank's rigorous standards while maximizing the functional insights gained from viral sequence information, directly supporting broader research goals in viral gene function and evolution [46] [5].

The journey from raw viral sequence data to a validated GenBank submission involves multiple stages of processing, annotation, and validation. The following workflow provides a visual representation of this end-to-end process, highlighting key decision points and procedural stages that will be elaborated in subsequent sections.

Materials and Reagents

Computational Tools and Databases

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for Viral Sequence Annotation and Submission

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application in Viral Research |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER Suite [46] | Protein domain identification using hidden Markov models | Detection of conserved viral protein domains (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 RBD) |

| Pfam/SUPERFAMILY [46] | Curated databases of protein domain families | Reference HMM libraries for viral protein domain annotation |

| FANTASIA Pipeline [7] | Functional annotation using protein language models | Annotation of viral "dark proteome" beyond traditional homology |