Comparative Analysis of Molecular Methods for SARS-CoV-2 Detection: From RT-qPCR and LAMP to NGS and Antigen Tests

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of molecular diagnostic methods for SARS-CoV-2, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Methods for SARS-CoV-2 Detection: From RT-qPCR and LAMP to NGS and Antigen Tests

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of molecular diagnostic methods for SARS-CoV-2, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of major testing platforms including RT-qPCR, RT-LAMP, rapid antigen tests, and next-generation sequencing. The scope encompasses methodological applications across clinical and research settings, troubleshooting for optimization, and rigorous validation frameworks according to international standards. By synthesizing recent performance data on sensitivity, specificity, variant detection capability, and operational requirements, this review serves as a critical resource for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific applications from clinical diagnosis to genomic surveillance.

Fundamental Principles and Evolving Landscape of SARS-CoV-2 Molecular Diagnostics

The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in late 2019 initiated a global health crisis, making accurate and reliable diagnostic testing a cornerstone of pandemic control efforts [1]. SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus with a genome approximately 30 kilobases in length, encoding both structural and non-structural proteins critical for its replication and pathogenesis [2] [1]. Among molecular diagnostics, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) has emerged as the undisputed gold standard for detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA in clinical specimens due to its superior sensitivity and specificity [3] [1] [4]. This method allows for the direct detection of viral genetic material, enabling identification of infected individuals even during the pre-symptomatic phase.

The reliability of RT-qPCR diagnostics fundamentally depends on the selection of appropriate viral gene targets. The most frequently targeted genes in SARS-CoV-2 detection assays are the envelope (E), nucleocapsid (N), RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), and spike (S) genes [3] [1]. Each target offers distinct advantages and limitations concerning conservation, abundance, and specificity, influencing the overall performance of diagnostic assays. This review provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of RT-qPCR methodologies and target gene selection, synthesizing experimental data from multiple studies to guide researchers and clinicians in optimizing SARS-CoV-2 detection strategies.

Comparative Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Target Genes

The design of effective RT-qPCR assays requires careful consideration of the targeted genomic regions. The ideal target combines high analytical sensitivity with robust specificity for SARS-CoV-2 while remaining conserved across emerging variants. The four primary targets—E, N, RdRP, and S genes—serve different biological functions and exhibit varying degrees of conservation.

The RdRP gene, located within the ORF1ab region, encodes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, a critical non-structural protein responsible for viral RNA replication [5] [6]. As an essential component of the replication machinery, this gene is highly conserved among coronaviruses, though specific primer sets can be designed for SARS-CoV-2 specificity [6]. Studies have demonstrated that assays targeting RdRP exhibit some of the highest analytical sensitivities available [6]. The N gene, which encodes the nucleocapsid protein that packages viral RNA, is abundantly expressed during infection, potentially enhancing detection sensitivity [3] [1]. This combination of conservation and abundance makes it a reliable target, though some studies have noted that its sensitivity may be slightly inferior to RdRP in certain assay configurations [7].

The E gene, encoding the small envelope protein, is considered the most sensitive target for detecting SARS-CoV-2 and related beta-coronaviruses [8]. However, this broader reactivity can reduce specificity for SARS-CoV-2 exclusively, potentially leading to cross-reaction with other coronaviruses [3]. Consequently, the E gene often serves as an initial screening target, with positive results requiring confirmation by more specific targets. The S gene, which codes for the spike protein mediating host cell entry, has been particularly affected by mutations in variants of concern, compromising detection in some commercial assays [4]. This susceptibility to genetic drift makes it a less reliable single target but valuable for monitoring specific variants.

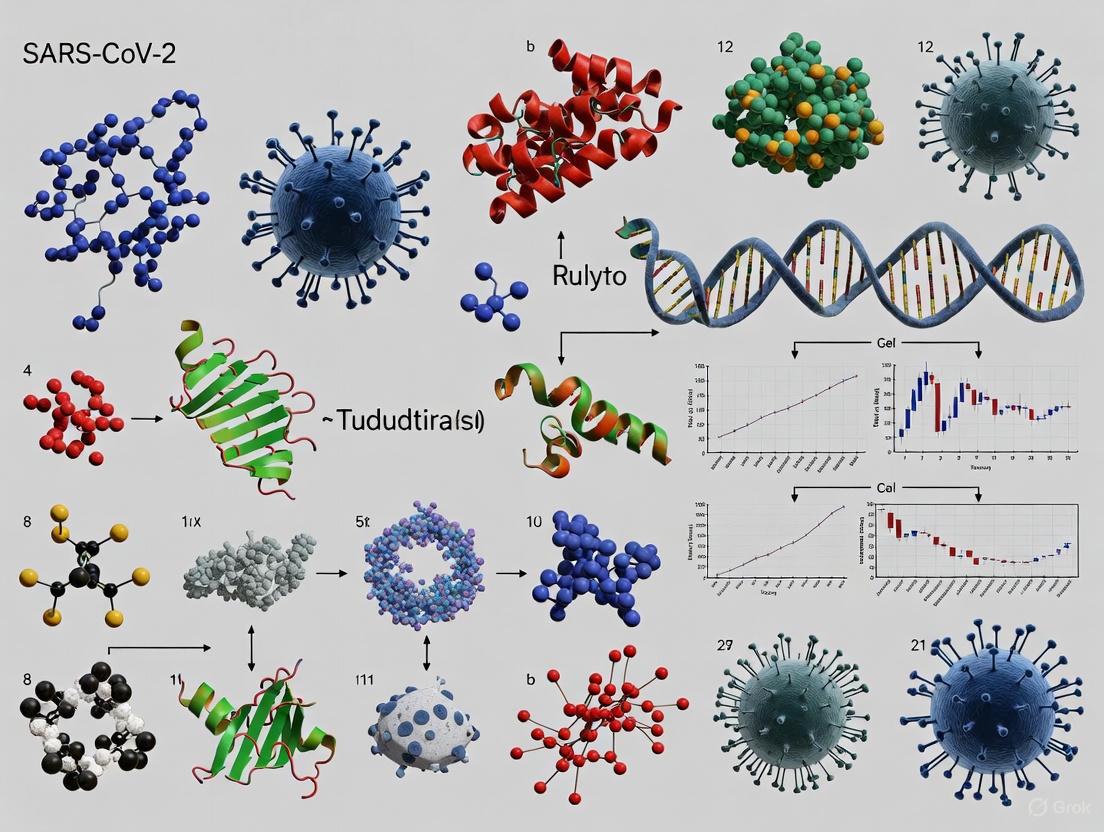

Figure 1: SARS-CoV-2 Target Gene Characteristics. This diagram illustrates the four primary gene targets used in RT-qPCR detection, their genomic classification, and key performance characteristics based on experimental data.

Performance Characteristics of Target Genes

Table 1: Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR Target Genes

| Target Gene | Sensitivity | Specificity | Conservation | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RdRP | High (LOD: 0.81-35.13 copies/μL) [7] [6] | High (SARS-CoV-2 specific) [6] | High (essential replication enzyme) [5] | Primary detection, confirmation [6] | Complex primer design due to conserved regions [6] |

| N | High (LOD: 0.81-20.31 copies/reaction) [7] [6] | High (SARS-CoV-2 specific) [6] | Moderate (subject to variations) [4] | Primary detection, screening [3] | Potential sensitivity reduction in variants [4] |

| E | Very High (excellent sensitivity) [8] | Moderate (cross-reacts with other β-coronaviruses) [3] [8] | Moderate | Initial screening [8] | Requires confirmatory testing with specific targets [8] |

| S | Variable | High (SARS-CoV-2 specific) | Low (frequent mutations in VOCs) [4] | Variant monitoring [4] | Reduced detection in variants due to mutations [4] |

Comparative Performance of Commercial RT-qPCR Kits

Multiple studies have systematically evaluated the performance of commercially available RT-qPCR kits, revealing significant differences in sensitivity, cost, and reliability. These comparative analyses are essential for laboratories to select appropriate testing platforms based on their specific needs and resources.

Analytical Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Independent validation studies have demonstrated substantial variation in the limit of detection (LOD) across different commercial kits. A 2023 comprehensive evaluation of three widely used tests revealed that the Liferiver and TaqPath kits both achieved an LOD of 10 viral RNA copies per reaction, while the Vitassay kit showed a slightly higher LOD of 100 viral RNA copies per reaction [4]. Importantly, this study noted that mean Ct values at low viral concentrations (10 copies/reaction) were significantly lower than the cutoff values declared by manufacturers, highlighting the importance of internal validation rather than relying solely on manufacturer claims [4].

A separate comparison of the BGI and Norgen Biotek systems found that the BGI detection system provided overall superior performance with lower detection limits and lower Ct values, generating comparable results to original clinical diagnostic data [2] [9]. The BGI system effectively identified samples across a wide dynamic range, from 65 copies to 2.1 × 10⁵ copies of viral genome/μl [2]. Meanwhile, the Norgen system, while more cost-effective, accurately detected only samples with clinical Ct values < 33-34, indicating reduced sensitivity for low viral loads [2] [9].

Diagnostic Accuracy and Clinical Performance

Clinical performance evaluations have revealed concerning variability in sensitivity among commercial kits. A study evaluating the AccuPower SARS-CoV-2 Real Time RT-PCR Kit (Bioneer, South Korea) reported a sensitivity of only 78.9% compared to the CDC EUA kit gold standard, with an estimated limit of detection higher than 40,000 viral RNA copies/mL [8]. This poor performance was particularly notable for samples with low to moderate viral loads, potentially missing more than 20% of true positive cases in surveillance programs [8].

In contrast, a 2021 comparison of Sansure Biotech, GeneFinder, and TaqPath kits found no statistically significant differences in their final results (p = 0.107), with all three demonstrating strong positive association and high Cohen's κ coefficient [3]. However, significant differences emerged in average Ct values for ORF1ab and N gene amplification (p < 0.001), with Sansure Biotech showing slightly better diagnostic performance overall [3].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Commercial SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR Kits

| Kit Name | Target Genes | Limit of Detection | Clinical Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGI | Orf1ab, Actin (human control) [2] | 65 copies/μl [2] | High (matches clinical diagnosis) [2] | Superior sensitivity, low Ct values [2] | Higher cost, less flexible [2] |

| TaqPath (Thermo Fisher) | ORF1ab, N, S [4] | 10 viral RNA copies/reaction [4] | High [3] [4] | Multi-target design, reliable detection [3] [4] | S gene target dropout in variants [4] |

| Norgen Biotek | N (CDC N1 & N2), RNase P [2] | Detects samples with Ct < 33 [2] | Moderate (78.4% for direct detection) [2] | Significant cost savings [2] | Reduced sensitivity for low viral loads [2] |

| Liferiver | ORF1ab, N, E [4] | 10 viral RNA copies/reaction [4] | High [4] | Reliable performance, internal control [4] | - |

| Sansure Biotech | ORF1ab, N [3] | 200 copies/mL [3] | High (better diagnostic performance) [3] | Good sensitivity, reliable results [3] | - |

| AccuPower (Bioneer) | RdRP, E, IPC [8] | >40,000 copies/mL [8] | Low (78.9%) [8] | - | Poor sensitivity, no RNA quality control [8] |

Advanced Methodologies: Direct Detection and Multiplex Assays

Extraction-Free Direct Detection Methods

Direct RT-qPCR methods that bypass RNA extraction have emerged as promising alternatives to increase testing throughput and reduce costs, particularly during supply chain shortages. These approaches detect viral RNA directly from patient samples without prior nucleic acid purification. Research has demonstrated that simply adding an RNase inhibitor to direct reactions significantly improved detection, without requiring additional treatments like lysis buffers or boiling [2] [9]. The best direct methods detected approximately 10-fold less virus than conventional indirect methods with RNA extraction, but this simplified approach substantially reduced sample handling, assay time, and cost [2] [9].

The BGI system has shown particular utility for direct, extraction-free analysis, providing 78.4% sensitivity compared to standard methods [2] [9]. This approach maintained detection capability while offering significant operational advantages, making it valuable for high-throughput screening scenarios where ultimate sensitivity may be sacrificed for efficiency and resource conservation.

Multiplex RT-qPCR Assay Design

Multiplex RT-qPCR assays that simultaneously detect multiple viral targets alongside human internal controls have demonstrated enhanced diagnostic reliability. One optimized multiplex method targeting viral N, RdRP, and human RP genes achieved 100% positive percent agreement with clinical samples, with LOD values of 1.40 and 0.81 copies/μL for RdRP and N genes, respectively [6]. This approach improves detection probability in patients with low viral loads and incorporates internal controls to prevent false-negative results due to inefficient sampling or PCR inhibition [6].

The design of effective multiplex assays requires careful primer and probe selection to avoid secondary structures such as homo-dimers, hetero-dimers, and hairpins that reduce amplification efficiency [6]. Successful implementations utilize distinct fluorescent dyes for each target (e.g., FAM for RdRP, HEX for N, ROX for RP) and optimized reaction conditions to maintain sensitivity across all targets [6].

Figure 2: RT-qPCR Workflow: Direct vs. Indirect Methods. This diagram compares the standard indirect method requiring RNA extraction with the direct detection approach, highlighting key advantages of each methodology.

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Protocols

Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Qiagen RNeasy, Invitrogen Purelink, BGI Magnetic Bead, Norgen Biotek Total RNA [2] | Isolation of high-quality viral RNA from clinical specimens | Most procedures performed similarly in comparative studies [2] |

| RT-qPCR Master Mixes | One-step RT-qPCR Master mix (Solis BioDyne) [7], NEB Luna Universal One-Step Kit [2] | Combined reverse transcription and PCR amplification | SYBR green approaches exhibited reduced specificity vs. TaqMan [2] |

| Positive Controls | Synthetic Positive Template (SPT) oligonucleotides [7], Quantitative Synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA [4] | Assay validation, sensitivity determination | SPT controls reduce false-positive risk from contamination [7] |

| Internal Controls | RNase P (human gene) [2] [6], MS2 phage [4] | Monitoring RNA extraction efficiency, PCR inhibition | Essential for distinguishing true negatives from assay failures [2] |

| Primer/Probe Sets | CDC N1/N2, Charité/Berlin protocol, custom designs [7] [6] | Target-specific amplification and detection | Multiplex designs require careful optimization to avoid dimer formation [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Multiplex RT-qPCR Detection

Based on optimized methodologies from recent studies, the following protocol enables reliable detection of SARS-CoV-2 through multiplex RT-qPCR:

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction:

- Collect nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs and place in viral transport medium (VTM)

- Extract RNA using approved magnetic bead-based or column-based methods (e.g., Magna Pure Compact, Roche or ELITe InGenius systems) [6]

- Use input volumes of 100-400 μL with elution volumes of 32-100 μL [2] [6]

- Include internal control (e.g., RNase P) to monitor extraction efficiency [2]

Multiplex RT-PCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare reaction mixture containing:

- Use distinct fluorescent dyes for different targets (FAM for RdRP, HEX for N, ROX for RP) [6]

- Include positive and negative controls in each run [4]

Amplification Conditions:

- Reverse transcription: 15-30 minutes at 45-50°C [3] [6]

- Initial denaturation: 2-3 minutes at 95°C [3]

- 40-45 cycles of:

- Data collection during annealing/extension phase

Result Interpretation:

- Analyze amplification curves and Ct values

- Use predetermined cutoff values (e.g., Ct ≤37-40 for positive result) [2] [4]

- Interpret based on multi-target detection patterns

- Verify internal control amplification to validate negative results

The comparative analysis of RT-qPCR methodologies for SARS-CoV-2 detection reveals a complex landscape where target selection, assay design, and commercial kit choice significantly impact diagnostic performance. The RdRP and N genes emerge as the most reliable targets, offering an optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity, while the E gene serves as a sensitive screening target and the S gene provides utility for variant monitoring. Among commercial platforms, significant variability exists, with BGI and TaqPath systems demonstrating superior sensitivity, while other kits offer cost-effective alternatives with moderate performance compromises.

The emergence of direct detection methods and optimized multiplex assays represents significant advancements, addressing needs for increased throughput and enhanced reliability. These methodologies, combined with careful internal validation of commercial tests, enable laboratories to implement robust SARS-CoV-2 detection pipelines tailored to their specific requirements and resources. As the virus continues to evolve, ongoing evaluation of primer compatibility with emerging variants remains essential for maintaining diagnostic accuracy, reinforcing the need for flexible, multi-target detection strategies in SARS-CoV-2 research and clinical diagnostics.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the critical need for rapid, reliable, and accessible molecular diagnostic methods. Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP) has emerged as a powerful alternative to the gold standard Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR), particularly in resource-limited settings [10]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these technologies, focusing on their principles, performance characteristics, and implementation requirements to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their selection of appropriate molecular methods for SARS-CoV-2 research and diagnostics.

RT-LAMP is a nucleic acid amplification technique that operates at a constant temperature, typically 60-65°C, eliminating the need for thermal cyclers required in PCR-based methods [10]. The technique utilizes a DNA polymerase with high strand displacement activity and specifically designed primer sets to amplify target RNA sequences after an initial reverse transcription step. The amplification products can be detected through various methods including turbidity, colorimetric changes, or fluorescence, often in less than 30 minutes [11] [12].

Principles of RT-LAMP Technology

Molecular Mechanism

The RT-LAMP reaction employs four to six primers that recognize six to eight distinct regions on the target DNA, ensuring high specificity [13]. The core primer set consists of:

- Forward and Backward Outer Primers (F3 and B3): Initiate the reaction

- Forward and Backward Inner Primers (FIP and BIP): Contain complementary sequences that form loop structures for continuous amplification

- Loop Primers (LF and LB): Optional primers that accelerate reaction kinetics by binding to loop regions [14]

This multi-primer system enables a cyclic amplification process involving strand displacement DNA synthesis that generates stem-loop DNA structures with multiple inverted repeats of the target. These structures then serve as templates for subsequent amplification rounds, leading to exponential DNA amplification under isothermal conditions [14].

Detection Methods

Various detection strategies have been developed for RT-LAMP:

Colorimetric Detection: Utilizes pH-sensitive dyes that change color as amplification progresses due to pyrophosphate ion release and subsequent pH drop in the reaction mixture [10] [12].

Turbidity Measurement: Monitors white magnesium pyrophosphate precipitate formation, which increases turbidity proportional to amplified DNA [14].

Fluorescent Detection: Employs intercalating dyes or sequence-specific molecular beacons that fluoresce when bound to double-stranded DNA [15] [11].

Molecular Beacons: Structured oligonucleotide probes with fluorophore and quencher that separate upon binding to specific sequences, increasing fluorescence with high specificity [15].

The following diagram illustrates the core RT-LAMP workflow and detection mechanisms:

Comparative Performance Analysis

Diagnostic Accuracy in Clinical Settings

Multiple clinical studies have validated RT-LAMP performance against RT-qPCR across diverse geographical settings:

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of RT-LAMP Compared to RT-qPCR

| Study Characteristics | Sensitivity | Specificity | Sample Type | Viral Load Dependency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multicenter study (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Italy) [10] | 87% (overall)97% (Ct < 35) | 98% | Pharyngeal swabs | Highly dependent on viral load |

| Japanese hospital study (disease timeline) [16] | 100% (≤9 days after onset)25% (≥10 days after onset) | 100% | Nasopharyngeal swabs | Strong time-dependent performance |

| Iranian clinical evaluation [13] | 93% agreement (saliva)94% agreement (nasopharynx) | 93% agreement (saliva)94% agreement (nasopharynx) | Saliva & nasopharyngeal | Consistent across sample types |

| Indonesian hospital study [12] | 65.5% (overall)73.2% (3-7 days post-onset) | 100% | Saliva | Optimal in early symptomatic phase |

Limit of Detection and Dynamic Range

Analytical sensitivity studies demonstrate RT-LAMP's capability to detect low viral concentrations:

Table 2: Analytical Sensitivity of RT-LAMP Assays

| Study | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Dynamic Range | Target Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-LAMP-MS assay [11] | 10-1 PFU mL-1 | 103 to 10-1 PFU mL-1 | RdRP gene |

| Japanese clinical evaluation [16] | 6.7 copies/reaction | Not specified | Not specified |

| Indonesian saliva study [12] | 50 copies/μL | Not specified | Not specified |

Experimental Protocols

Standard RT-LAMP Workflow

A typical RT-LAMP protocol for SARS-CoV-2 detection involves these critical steps:

Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect nasopharyngeal, saliva, or other respiratory specimens [13] [12]

- For saliva: participants should refrain from eating, drinking, or smoking for 1 hour before collection [12]

- Heat inactivation at 65°C for 15 minutes to ensure biosafety [12]

RNA Extraction:

- Use commercial RNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit) [16]

- Automated extraction systems (e.g., QIAcube) can standardize the process [16]

- Evaluate RNA purity spectrophotometrically (260/280 ratio ~2.0) [13]

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare 25μL reaction mixture containing:

- Add detection reagents (colorimetric dye, fluorescent probes, or molecular beacons as required) [15]

Amplification and Detection:

- Incubate at 62-65°C for 20-40 minutes [11] [13]

- Monitor amplification in real-time using turbidimetry, fluorescence, or visual color change [15] [12]

- Interpret results: color change from pink to yellow (colorimetric) or increased turbidity/fluorescence indicates positive amplification [12]

The following workflow details the specific steps for molecular beacon-enhanced RT-LAMP:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RT-LAMP Experiments

| Reagent/Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Strand-displacing DNA polymerase for isothermal amplification | Commercial kits (e.g., Loopamp kit, New England Biolabs Bst polymerase) [13] [14] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts RNA template to cDNA | AMV Reverse Transcriptase (200 U/reaction) [14] |

| LAMP Primers | Target-specific amplification | Designed using Primer Explorer V5; 4-6 primers targeting 6-8 regions of SARS-CoV-2 genes (ORF1ab, N, E, RdRP) [13] [14] |

| Molecular Beacons | Sequence-specific detection with fluorophore-quencher pairs | Locked nucleic acid-modified beacons for enhanced temperature stability [15] |

| Reaction Buffer | Optimal enzymatic activity | Contains MgSO₄, betaine, dNTPs, KCl in Tris-HCl buffer [14] |

| Detection Reagents | Visual or fluorescent signal generation | Calcein (colorimetric), SYBR Green (fluorescent), or magnesium pyrophosphate (turbidity) [11] [14] |

Advantages and Limitations in Research Applications

Technical Advantages

RT-LAMP offers several compelling advantages for SARS-CoV-2 research:

Operational Simplicity: Eliminates need for sophisticated thermal cyclers; reactions proceed at constant temperatures (typically 65°C) using simple heating blocks or water baths [10]. This significantly reduces equipment costs and operational complexity compared to RT-qPCR.

Rapid Results: Amplification and detection typically completed within 30-40 minutes, substantially faster than conventional RT-qPCR protocols which often require 1.5-2 hours [11] [12].

Robust Detection Methods: Multiple readout options including colorimetric (visible to naked eye), turbidity, or fluorescence enable flexibility for different laboratory settings [15] [12].

Sample Compatibility: Works effectively with various sample types including saliva, nasopharyngeal swabs, and other respiratory specimens without requiring complex processing [13] [12].

Performance Considerations

Sensitivity Profile: While RT-LAMP demonstrates excellent sensitivity for medium to high viral loads (Ct < 35), its performance decreases with lower viral concentrations, making it particularly suitable for identifying actively infectious individuals [10] [16].

Time-Dependent Sensitivity: Clinical studies show optimal performance during early infection stages (up to 9 days post-symptom onset), with significantly reduced sensitivity during later stages when viral loads decline [16].

Multiplexing Potential: Molecular beacon approaches enable multiplex detection of several targets in single reactions, including simultaneous detection of viral and human control RNA to verify sample integrity [15].

RT-LAMP technology represents a significant advancement in molecular detection methods, offering a balanced combination of speed, accessibility, and reliability. While RT-qPCR remains the gold standard for maximum sensitivity, particularly at low viral concentrations, RT-LAMP provides an excellent alternative for rapid screening, resource-limited settings, and point-of-care applications. The technology's particular strength in identifying cases with higher viral loads makes it exceptionally valuable for public health interventions aimed at curbing transmission. For researchers and drug development professionals, RT-LAMP offers a versatile platform that can be adapted to various experimental needs, from basic viral detection to sophisticated multiplex assays incorporating internal controls and specific probe-based detection systems.

Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) have become indispensable tools in the management and study of SARS-CoV-2, offering a distinct alternative to molecular methods like reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Their value lies in the unique combination of speed, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness, enabling decentralized testing and near-in-time results critical for early isolation and transmission interruption [17] [18]. The core technology underpinning most RATs is the lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA), a platform designed to detect specific viral proteins, or antigens, from patient samples [17].

For researchers and scientists engaged in a comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic methods, understanding the precise mechanisms, performance boundaries, and technical protocols of RATs is paramount. This guide provides a detailed examination of RATs, placing their performance within the broader context of molecular diagnostics. It summarizes key experimental data, delineates foundational methodologies, and outlines essential research reagents, thereby equipping professionals with the necessary framework for critical evaluation and application of these tests in both clinical and research settings.

Immunoassay Mechanism: The Lateral Flow Assay

The operational principle of most rapid antigen tests is the lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA), a robust technology that leverages antibody-antigen interactions on a nitrocellulose membrane to generate a visual signal [17]. The process is engineered for simplicity and speed, typically yielding results within 10-30 minutes without requiring specialized equipment [18].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential flow and key components of a typical lateral flow assay for SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection.

Core Components and Signaling Pathway

The signaling pathway within an LFIA involves a cascade of specific biochemical reactions, as shown in the workflow below.

Performance Comparison: Antigen Tests vs. Molecular Methods

A critical component of SARS-CoV-2 research involves the comparative analysis of diagnostic test performance. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of rapid antigen tests against molecular methods like RT-PCR.

Table 1: Comparative Performance: Rapid Antigen Tests vs. Molecular Methods

| Performance Feature | Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) | Molecular Tests (e.g., RT-PCR, POC NAATs) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Molecule | Viral surface proteins (antigens) [18] | Viral genetic material (RNA) [18] |

| Technology Platform | Lateral Flow Immunoassay (LFIA) [17] | Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT), including PCR and isothermal amplification [18] |

| Typical Turnaround Time | 10–30 minutes [18] | 15–45 minutes (POC NAATs) to several hours (lab-based) [18] |

| Analytical Sensitivity (LOD) | Moderate; requires higher viral load [19] | High; can detect very low viral copies [20] |

| Clinical Sensitivity (Symptomatic) | ~80-85% (early symptoms) [18]; 90.4% in a recent study [19] | >95% [20] [18] |

| Clinical Specificity | High (>97-99%) [19] [18] | Very High (>99%) [18] |

| Best Use Case | High-prevalence settings, rapid screening, early symptomatic phase [18] | High-stakes diagnosis, low-prevalence settings, asymptomatic detection [18] |

| Cost per Test | Low [18] | Moderate to High [18] |

| Equipment Needs | Minimal to none [18] | Analyzer required [18] |

| Multiplex Capability | Rare [18] | Common (e.g., respiratory panels) [18] |

The Impact of Viral Load on Test Sensitivity

The sensitivity of RATs is not static; it is highly dependent on the viral load present in the patient sample, which is often inversely correlated with RT-PCR Cycle Threshold (Ct) values [19]. One study demonstrated a clear correlation between low Ct values (indicating high viral load) and high RAT sensitivity. The sensitivity was 96.5% for samples with Ct <22, but dropped significantly to 80.5% for Ct 22-26, and only 30.8% for Ct >26 [19]. This performance characteristic underscores a critical limitation of RATs: their significantly reduced ability to detect infections in individuals with low viral loads, which is common in pre-symptomatic, late-stage, or asymptomatic infections [20].

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

For researchers validating the performance of rapid antigen tests, the following core experimental protocols provide a framework for generating comparable and reliable data.

Protocol 1: Diagnostic Accuracy Study vs. RT-PCR

This protocol is designed to evaluate the clinical sensitivity and specificity of a RAT against the reference method of RT-PCR.

- 1. Sample Collection: Obtain simultaneous paired oro-nasopharyngeal swabs from a cohort of symptomatic adult patients [19].

- 2. Sample Processing:

- 3. RT-PCR Analysis: Perform RT-PCR testing targeting established SARS-CoV-2 genes (e.g., RdRp, N, E). Record Ct values for all positive samples [19].

- 4. Data Analysis:

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) using RT-PCR results as the reference standard.

- Stratify RT-PCR positive samples by Ct value ranges (e.g., <22, 22-26, >26) and calculate the sensitivity of the RAT for each group [19].

Protocol 2: Limit of Detection (LOD) Determination

This protocol establishes the lowest concentration of the virus that the RAT can reliably detect.

- 1. Sample Preparation: Create serial dilutions of inactivated SARS-CoV- virus or recombinant nucleocapsid protein in a synthetic matrix that mimics nasal fluid [17].

- 2. Test Execution: Apply each dilution to the RAT cartridge. The number of replicates per dilution (e.g., n=20) should be sufficient for statistical analysis [17].

- 3. Data Analysis: The LOD is defined as the lowest virus concentration at which ≥95% of the test replicates produce a positive result [17].

- 4. Correlation with Ct Value: Where possible, correlate the dilution factor with the Ct value obtained from RT-PCR testing of the same material to bridge analytical and clinical sensitivity [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The development and validation of rapid antigen tests rely on a specific set of biological and chemical reagents. The following table details these essential materials and their functions in the research context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Rapid Antigen Test Development

| Research Reagent | Function and Role in Assay Development |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | Core detection elements; highly specific mAbs target SARS-CoV-2 antigens (e.g., nucleocapsid protein). Different mAbs are used for capture (on test line) and detection (conjugated to labels) [17]. |

| Nucleocapsid (N) Protein | The primary target antigen for most SARS-CoV-2 RATs. Used as a standard (recombinant protein) for assay development, optimization, and calibration [17]. |

| Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles | A common label for conjugation to detection antibodies. Provides a red color at the test line, allowing for visual interpretation of results without instrumentation [17]. |

| Nitrocellulose Membrane | The platform on which the immunoassay occurs. Its porous structure facilitates capillary flow and serves as the solid support for immobilizing capture antibodies at the test and control lines [17]. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | A solution used to store and transport patient swab samples while maintaining viral integrity. Essential for comparative studies against RT-PCR [19]. |

| Positive Control Swabs | Swabs containing inactivated virus or recombinant antigen at a known concentration. Critical for verifying test performance, lot-to-lot consistency, and operator competency [19]. |

Within the comparative framework of SARS-CoV-2 research methodologies, rapid antigen tests occupy a vital, defined niche. Their immunoassay mechanism, based on lateral flow technology, provides unparalleled speed and operational simplicity, making them powerful tools for mass screening and rapid triage in high-prevalence scenarios [18]. However, this utility is bounded by a well-documented performance characteristic: lower analytical sensitivity compared to molecular methods, leading to a higher likelihood of false-negative results in cases of low viral load [20] [19].

For the research and development community, the future of RATs lies in addressing these limitations. Emerging trends include the integration of digital readers to minimize user interpretation error and enhance signal quantification, the development of multiplex platforms capable of simultaneously differentiating between SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and RSV, and the exploration of novel labels and signal amplification techniques to push sensitivity closer to molecular standards without sacrificing speed [18]. A thorough understanding of the mechanisms, performance data, and experimental protocols detailed in this guide provides the foundational knowledge necessary to drive this innovation forward, ultimately enhancing our diagnostic capabilities against current and future pathogenic threats.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is the cornerstone of modern genomic surveillance, enabling scientists to track the evolution and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the primary NGS methods and platforms used in SARS-CoV-2 research, supporting researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their surveillance objectives.

Two primary enrichment methods are used to target the SARS-CoV-2 genome for sequencing: tiling multiplex PCR and sequence hybridization capture [21]. Each method has distinct advantages depending on sample quality and research goals.

- Tiling Multiplex PCR: This approach uses multiple overlapping primer pairs to amplify the entire viral genome into small fragments. It is highly sensitive and efficient for samples with moderate to high viral loads, making it the most common strategy for clinical samples [21] [22]. Common protocols include ARTIC and its derivatives.

- Sequence Hybridization Capture: This method uses biotinylated probes (baits) to hybridize and pull down viral sequences from a pool of nucleic acids. It is particularly useful for samples with low viral load or significant host background, as it is less prone to amplification bias and can handle more diverse sequences [21].

Performance Comparison of NGS Methods and Platforms

The performance of different NGS workflows varies significantly based on the protocol, sequencing technology, and sample quality. The tables below summarize key performance metrics from recent comparative studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Whole Genome Sequencing Protocols for SARS-CoV-2

| Sequencing Protocol | Median Genome Coverage (Ct ≤ 30) | Key Advantages | Noted Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARTIC (v3 & v4.1) [23] | ~99% (with cell culture variants) | High PCR amplicon yield and genome completeness; accurate lineage calling [23]. | Performance can drop with very low viral titers [23]. |

| Illumina AmpliSeq [22] | 99.8% | Very high genome coverage [22]. | |

| EasySeq (Illumina) [22] | ~99% (included in study) | High proportion of SARS-CoV-2 reads; low hands-on time [22]. | |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) [22] | 81.6% | Shortest sequence runtime; low hands-on time; capable of detecting structural variations [22]. | Lower genome coverage compared to other methods [22]. |

| Ion AmpliSeq (Thermo Fisher) [22] | ~99% (included in study) | High genome coverage [22]. | |

| QNome Nanopore [24] | 89.35% (on clinical samples) | Effective for structural variation detection; real-time analysis [24]. | Lower read accuracy and fewer "good" consensus genomes vs. MGI [24]. |

| MGI DNBSEQ [24] | 90.39% (on clinical samples) | High sensitivity for mutation detection [24]. |

Table 2: Cross-Platform Sequencing Performance Metrics

| Performance Parameter | Illumina Systems [22] | Ion Torrent Systems [22] | Oxford Nanopore (ONT) [22] | QNome Nanopore [24] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Read Type | Short-read | Short-read | Long-read | Long-read |

| Hands-on Time | Low (EasySeq) to Moderate [22] | Low [22] | ||

| Sequence Runtime | Moderate to Long [22] | Short [22] | ||

| Variant Calling | Accurate for SNVs and small indels [24] | Accurate for SNVs and small indels | Accurate consensus-level sequences [24] [22] | Accurate consensus-level sequences; good for large deletions [24] |

| Error Rate | Low | Low | Higher single-read error rate, but accurate at consensus [24] | Higher single-read error rate [24] |

Experimental Protocols for SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing

Benchmarking of Amplicon-Based Protocols

A 2025 study compared five amplicon-based WGS protocols (ARTIC v3, ARTIC v4.1, QIAseq DIRECT SARS-CoV-2, SNAP, and Midnight) using synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA and cell culture-derived variants titrated to represent high, medium, and low viral loads [23].

- Sample Preparation: The study used Twist Synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA Control and six cell-cultured SARS-CoV-2 variants (B.1, B.1.1.7, B.1.351, P.1, B.1.617.2, and BA.1). Viral RNA was extracted using a bead-based purification kit and reverse-transcribed to cDNA [23].

- Protocol Evaluation: The protocols were compared based on PCR amplicon yield, genome completeness (percentage of the genome covered at a sufficient depth), and accuracy in lineage calling [23].

- Key Findings: The ARTIC protocols, particularly v4.1, yielded the highest number of amplicons and showed the highest genome completeness across different viral titers. Although the SNAP protocol yielded the fewest amplicons, it showed high genome completeness for the synthetic genome at high titre [23].

Nanopore vs. Short-Read Sequencing

A 2024 study directly compared the performance of the QNome nanopore platform against the short-read MGI platform [24].

- Sample Collection: The study utilized 120 clinical nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) samples with Ct values below 30, alongside synthetic SARS-CoV-2 controls [24].

- Uniform Enrichment and Sequencing: For a fair comparison, RNA from all samples was extracted, reverse-transcribed, and amplified using the ARTIC v4.1 primer set. The resulting amplicons were then split and used for library preparation on both the QNome and MGI platforms [24].

- Analysis Metrics: The platforms were compared on read length, mapping quality, genome coverage, mutation detection sensitivity, and phylogenetic concordance of assigned Pango lineages [24].

Research Reagent Solutions for SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for SARS-CoV-2 NGS

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Example Use in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| ARTIC Primer Panels (v3, v4, v4.1) [23] [24] | Tiling multiplex PCR for whole-genome amplification of SARS-CoV-2. | Used for initial cDNA amplification in both ONT and Illumina protocols [23] [24]. |

| Twist Synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA Control [23] | A defined synthetic RNA control for benchmarking protocol performance. | Served as a control material in the benchmarking study [23]. |

| iScript Advanced cDNA Synthesis Kit [22] | Reverse transcription of viral RNA into cDNA for subsequent PCR. | Used in the EasySeq RC-PCR protocol [22]. |

| Agenmic SARS-CoV-2 Target Enrichment Kit [24] | A commercial kit for PCR-based enrichment of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. | Used for cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification in the QNome vs. MGI study [24]. |

| AmpliSeq SARS-CoV-2 Panel (Illumina) [22] | A targeted amplicon panel for SARS-CoV-2 sequencing on Illumina systems. | Used for library preparation and sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 [22]. |

| Ion AmpliSeq SARS-CoV-2 Insight Assay (Thermo Fisher) [22] | A targeted amplicon panel for SARS-CoV-2 sequencing on Ion Torrent systems. | Used for library preparation and sequencing on Ion Torrent platforms [22]. |

Workflow Visualization of NGS Methods

The following diagram illustrates the two main NGS workflows for SARS-CoV-2, highlighting the key divergences in the enrichment step.

The choice of NGS method for SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance involves trade-offs. For most clinical samples with reliable viral loads, tiling multiplex PCR protocols like ARTIC on either short-read (Illumina) or long-read (ONT) platforms offer a robust, sensitive, and cost-effective solution. For challenging samples with very low viral load or high levels of contamination, hybridization capture methods may provide better coverage. The ongoing development of methods like ARTIC-Amp, which adds a rolling circle amplification step to boost yield, shows promise for further enhancing sensitivity for environmental and wastewater surveillance [23].

The rapid and accurate detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been a cornerstone of the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) remains the gold standard for molecular diagnosis, the pandemic has acted as a catalyst for the development of novel diagnostic platforms that offer advantages in speed, portability, and ease of use [25] [26]. Among these, technologies based on Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and other isothermal amplification methods have shown exceptional promise for point-of-care (POC) testing and field deployment. This comparative analysis examines the performance, experimental protocols, and technical characteristics of these emerging platforms within the broader context of molecular methods for SARS-CoV-2 research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a critical evaluation of the current diagnostic landscape.

The emerging diagnostic platforms for SARS-CoV-2 detection primarily leverage two core principles: CRISPR-Cas systems for specific nucleic acid recognition and isothermal amplification for rapid nucleic acid amplification without specialized thermal cycling equipment.

CRISPR-Cas Systems utilize Cas proteins (e.g., Cas12, Cas13) that, upon recognition of a specific viral RNA sequence through a guide CRISPR RNA (crRNA), exhibit collateral cleavage activity. This activity enables them to degrade reporter molecules, generating a detectable fluorescent or colorimetric signal [25] [27]. The programmable nature of CRISPR-Cas systems allows for high specificity, which is particularly valuable for distinguishing between different SARS-CoV-2 variants [28].

Isothermal Amplification Methods, such as Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) and Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA), amplify nucleic acids at a constant temperature. This eliminates the need for thermal cyclers, making them suitable for resource-limited settings [25] [29]. These methods are often coupled with CRISPR-Cas systems to enhance sensitivity or with other detection mechanisms to create integrated diagnostic platforms.

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics of major emerging platforms compared to the reference standard, RT-qPCR.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Detection Platforms

| Technology | Principle | Limit of Detection | Time to Result | Clinical Sensitivity | Clinical Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction | 100-1000 copies/μL [26] | 1-4 hours [30] | Gold Standard | Gold Standard |

| CRISPR-Cas (e.g., CALIBURN-v2) | CRISPR-Cas12a with isothermal pre-amplification | ~100-fold improvement vs earlier platforms [28] | ~25 minutes [28] | 94.38%-95.56% [28] | Not specified |

| AND-gated CRISPR-Cas12 | Dual-gene (ORF1ab & N) logic-gated CRISPR | 4.3 aM (~3 copies/μL) [31] | <50 minutes [31] | 100% [31] | 100% [31] |

| RHAM | RNase HII-assisted LAMP amplification | 5×10² copies/mL [29] | 10-25 minutes [29] | 100% [29] | 100% [29] |

| nGQD-SPR Biosensor | Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dot surface plasmon resonance | 0.01 pg/mL [30] | Real-time (minutes) [30] | Not specified | Not specified |

| Antigen Rapid Tests | Lateral flow immunoassay | Varies by viral load | 15-30 minutes | 71.2% (overall) [32] | 98.9% (overall) [32] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

CRISPR-Cas Systems with Isothermal Pre-amplification

A common and effective approach combines the high specificity of CRISPR-Cas systems with the amplification power of isothermal methods. The typical workflow involves sample preparation, nucleic acid amplification, and CRISPR-based detection.

Table 2: Key Steps in a Coupled RT-RPA/CRISPR-Cas12a Assay

| Step | Description | Key Components | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RNA Extraction | Isolation of viral RNA from nasopharyngeal swabs | TIANamp Virus DNA/RNA Kit [28] | Follow manufacturer's protocol |

| 2. Reverse Transcription Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RT-RPA) | Isothermal amplification of target RNA | Primer set (e.g., for N gene), rehydration buffer, magnesium acetate [28] | 42°C for 30 minutes [28] |

| 3. CRISPR-Cas Detection | Target-specific cleavage and signal generation | LbCas12a, crRNA, ssDNA fluorescent reporter, NEBuffer [28] | 37°C for 30 minutes [28] |

| 4. Signal Readout | Fluorescence or lateral flow detection | Fluorometer or lateral flow strip | Visual or instrument-based |

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas Detection Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps from sample collection to result readout in a typical CRISPR-based diagnostic assay.

Advanced CRISPR Configurations: AND-Gated Logic

To enhance specificity and reduce false positives, researchers have developed sophisticated CRISPR systems that require the presence of multiple viral targets. The AND-gated CRISPR-Cas12 system represents a significant innovation, as it necessitates the simultaneous detection of two distinct SARS-CoV-2 genes (ORF1ab and N) to generate a positive signal [31].

The experimental protocol involves:

- Reverse Transcription Free-Exponential Amplification Reaction (RTF-EXPAR): Viral RNA is converted and amplified into short single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) activators without a separate reverse transcription step. This is performed in two separate tubes, one for each target gene [31].

- CRISPR-Cas12a Activation Logic: The ssDNA activators from each target hybridize with the spacer region of their corresponding crRNA. Only when both activators are present does a stable ternary complex form, activating the trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a [31].

- Signal Generation: Activated Cas12a cleaves a reporter probe (e.g., fluorescent or lateral flow), yielding a detectable signal.

Figure 2: AND-Gated CRISPR-Cas12 Detection Logic. This system requires simultaneous detection of two distinct SARS-CoV-2 genes (ORF1ab and N) to activate the Cas12a enzyme and produce a signal, significantly enhancing specificity.

RNase HII-Assisted Amplification (RHAM)

The RHAM platform integrates LAMP with an RNase HII-mediated fluorescent reporter system to achieve rapid and specific detection in a single reaction [29]. The key differentiator of RHAM is its mechanism for reducing non-specific amplification, a common challenge in LAMP assays.

The experimental process is as follows:

- LAMP Amplification: Primers specific to SARS-CoV-2 targets (Orf1ab and N genes) initiate exponential amplification of the viral RNA at an isothermal temperature (60-65°C) using Bst DNA polymerase [29].

- Hybridization and Cleavage: A ribonucleotide-containing fluorescent probe, labeled with a fluorophore and a quencher, hybridizes specifically with the LAMP amplicon. The RNase HII enzyme recognizes and cleaves the RNA base within the DNA–probe duplex [29].

- Fluorescence Detection: Cleavage separates the fluorophore from the quencher, resulting in a fluorescent signal that can be monitored in real-time. The entire process, from sample to result, can be completed in under 25 minutes, even with unextracted clinical samples [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these novel diagnostic platforms relies on a specific set of reagents and materials. The table below details essential components and their functions in a typical CRISPR-based diagnostic assay.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-based SARS-CoV-2 Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Protein | Effector nuclease for target recognition and signal generation | LbCas12a (from Lachnospiraceae bacterium ND2006) [28] |

| crRNA | Guide RNA that confers specificity to the viral target | Designed against SARS-CoV-2 N, Orf1ab, or S genes [28] [31] |

| Isothermal Amplification Mix | Enzymes and reagents for amplifying viral RNA at constant temperature | RT-RPA Kit (e.g., AmpFuture) [28]; LAMP primers and Bst polymerase [29] |

| Fluorescent Reporter | Substrate for detecting collateral cleavage activity | ssDNA probe labeled with FAM (fluorophore) and BHQ1 (quencher) [28] |

| Nuclease-Free Buffers | Optimal reaction environment for enzymatic activity | NEBuffer with optimized Na+, Mg2+, DTT, and BSA concentrations [28] |

| Lateral Flow Strips | Platform for visual, instrument-free readout | Test strips with FAM- and biotin-labeled reporters [31] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The emergence of CRISPR-based and other novel detection platforms represents a paradigm shift in molecular diagnostics for infectious diseases. The comparative data clearly demonstrates that these technologies can achieve sensitivity comparable to RT-qPCR while offering significant advantages in speed, portability, and potential for point-of-care use [25] [28] [29]. The integration of isothermal amplification with CRISPR detection has been particularly successful, mitigating the limitations of each method when used alone [25].

The high specificity of CRISPR systems is a critical asset, not only for distinguishing SARS-CoV-2 from other respiratory pathogens but also for detecting specific variants of concern [28]. Innovations such as the AND-gated logic circuit further enhance diagnostic reliability by virtually eliminating false positives through dual-target verification [31]. Furthermore, platforms like RHAM and nGQD-SPR biosensors illustrate how refinements in signal generation and detection can lead to improvements in both speed and accuracy [29] [30].

For the research and drug development community, these platforms offer powerful tools beyond mere diagnosis. The ability to rapidly profile viral loads and characterize variants in near real-time can inform epidemiological models, therapeutic strategies, and vaccine development. Future developments will likely focus on streamlining workflows into single-step reactions, enhancing multiplexing capabilities for simultaneous pathogen detection, and integrating these systems with portable devices and Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) platforms for remote data collection and analysis [28]. As these technologies mature and become more accessible, they are poised to transform not only pandemic response but also routine infectious disease diagnostics.

Application-Specific Method Selection and Implementation Strategies

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) remains the gold standard for sensitive and reliable detection of RNA viruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [9] [33]. The unprecedented diagnostic demands of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical need for optimized, high-throughput laboratory workflows to enable rapid testing while maintaining analytical accuracy. Efficient diagnostic pipelines are essential not only for patient triaging and clinical decision-making but also for broader public health surveillance efforts [9] [33]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of automated RNA extraction systems, RT-qPCR detection methodologies, and streamlined protocols, presenting objective performance data to inform laboratory setup and reagent selection for molecular testing.

Comparative Analysis of RNA Extraction Systems

The initial step of RNA extraction is a critical determinant for the success of downstream RT-qPCR applications. Automated nucleic acid extraction systems have become indispensable in high-throughput settings, significantly reducing hands-on time and minimizing the risk of cross-contamination compared to manual methods [34] [35].

Performance Comparison of Automated Extraction Platforms

Various automated platforms utilizing magnetic bead-based technology have been developed and validated for SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction from nasopharyngeal swabs. The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of several tested systems.

Table 1: Comparison of Automated RNA Extraction Systems

| Extraction System / Kit | Technology | Processing Time | Sample Input Volume | Elution Volume | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Kit (MAGABIO PLUS VIRUS DNA/RNA PURIFICATION KIT II) [35] | Magnetic Beads (with Proteinase K) | ~35 minutes | 20-1000 µL | 80 µL | Found to have good efficiency and produced reproducible results; served as a reliable benchmark [35]. |

| Rapid Kit (MAGABIO PLUS VIRUS RNA PURIFICATION KIT II) [35] | Magnetic Beads (without Proteinase K) | ~9 minutes | 10-300 µL | 70 µL | Provided comparable analytical results to the standard kit but with significantly faster turnaround, improving workflow [35]. |

| EZ1 DSP Virus Kit on EZ1 Advanced XL robot [34] | Automated Magnetic Beads | Not Specified | 200 µL [36] | 100 µL [36] | Showed good efficiency and produced more reproducible results than the manual MagMAX method in a forensic evaluation [34]. |

| STARMag 96x4 Viral DNA/RNA Kit on Nimbus IVD platform [9] [36] | Automated Magnetic Beads | ~270 minutes total for extraction and RT-qPCR [36] | 200 µL | 100 µL | Used as the reference standard in clinical diagnostics; demonstrated high sensitivity and reliability [9] [36]. |

Experimental Protocol: RNA Extraction Comparison

A typical protocol for comparing RNA extraction methods, as used in several studies, involves the following steps [35]:

- Sample Collection: Nasopharyngeal swabs are collected from symptomatic individuals and placed in Universal Transport Medium (UTM).

- Sample Processing: A defined volume (e.g., 100-200 µL) of the UTM sample is used for nucleic acid extraction.

- Automated Extraction: Samples are processed on the automated platform according to the manufacturer's instructions. This typically involves lysis, binding of nucleic acids to magnetic silica particles, several wash steps, and final elution in a dedicated buffer.

- Quality Assessment: The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA can be assessed using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop), measuring absorbance ratios at 260/280 nm and 260/230 nm [35].

- Downstream Analysis: The eluted RNA is immediately used for RT-qPCR or stored at -80°C.

Comparative Analysis of RT-qPCR Detection Methods

Following RNA extraction, the choice of RT-qPCR detection method impacts sensitivity, specificity, cost, and throughput. The main methodologies include TaqMan probe-based assays and SYBR Green-based assays, which can be configured in one-step or two-step formats.

Performance Comparison of Detection Kits and Methods

Multiple RT-qPCR kits and methods have been rigorously evaluated against clinical diagnostic standards. The data below illustrates their comparative performance.

Table 2: Comparison of RT-qPCR Detection Kits and Methods

| Detection System / Method | Chemistry | Target Genes | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Findings / Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BGI Real-Time Fluorescent RT-PCR Kit [9] | TaqMan Probe (One-Step) | Not Specified | 100% (vs. clinical diagnosis) [9] | 100% (vs. clinical diagnosis) [9] | Overall superior performance with lower Ct values and higher sensitivity; suitable for direct, extraction-free detection (78.4% sensitivity) [9]. |

| Norgen 2019-nCoV TaqMan RT-PCR Kit [9] | TaqMan Probe (One-Step) | N1, N2 (CDC primers) | Accurately detected samples with clinical Ct < 33 [9] | High | Less sensitive than BGI but offered significant cost savings [9]. |

| Allplex 2019-nCoV Assay (Reference standard) [9] [36] | Multiplex TaqMan Probe (One-Step) | N, RdRp/S, E | High (Clinical Gold Standard) | High (Clinical Gold Standard) | Used as a benchmark in validation studies; demonstrated 100% analytical specificity [9] [36]. |

| Two-Step SYBR Green-based Method [37] | SYBR Green (Two-Step) | S, N | 88% (S gene), 84% (N gene) | 84% | Comparable sensitivity and specificity to one-step methods for samples with Ct ≤ 25; more prone to non-specific amplification [37]. |

| One-Step TaqMan Probe-based Method [37] | TaqMan Probe (One-Step) | RdRp, N | 92% (RdRp gene), 96% (N gene) | 86% | Considered the premier standard test; higher cost but generally more specific than SYBR Green [37]. |

Experimental Protocol: One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

The core methodological differences are as follows [37]:

A. One-Step RT-qPCR Protocol: This method combines reverse transcription and PCR amplification in a single reaction tube.

- Reaction Setup: A master mix containing reverse transcriptase, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, primers, probes (for TaqMan), and the extracted RNA template is prepared.

- Thermal Cycling: The reaction is run on a real-time PCR instrument with a programmed protocol: reverse transcription (e.g., 50°C for 20 min), initial denaturation (e.g., 95°C for 15 min), followed by 40-45 cycles of denaturation (e.g., 95°C for 10 s) and annealing/extension (e.g., 60°C for 15-60 s, with fluorescence acquisition) [37] [36].

B. Two-Step SYBR Green RT-qPCR Protocol: This method separates reverse transcription from the PCR amplification.

- cDNA Synthesis: Extracted RNA is first reverse transcribed into cDNA using a separate kit containing reverse transcriptase, primers, and dNTPs.

- qPCR Setup: A portion of the synthesized cDNA is then added to a qPCR master mix containing DNA polymerase, SYBR Green dye, and gene-specific primers.

- Thermal Cycling: The reaction is run with a standard qPCR cycling protocol (e.g., 95°C for 35 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 1 min), followed by a melt curve analysis to verify amplification specificity [37].

Emerging Workflows: Extraction-Free and Direct RT-qPCR

To further increase throughput and circumvent supply chain bottlenecks for RNA extraction kits, extraction-free direct RT-qPCR methods have been developed and validated.

Performance Data and Protocols

The primary direct methods involve using raw sample material with or without a heat inactivation step.

Table 3: Comparison of Extraction-Free Direct RT-qPCR Methods

| Method | Description | Sensitivity vs. Extraction-Based Method | Key Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unheated Extraction-Free (EFh-) [36] | Directly using a diluted UTM sample in the RT-qPCR reaction without any pre-treatment. | 100% [36] | Perfect agreement with standard method; reduces average processing time from ~270 min to ~156 min [36]. |

| Heated Extraction-Free (EFh+) [36] | Sample is heated to 95°C for 3-10 min to lyse cells/virus, then cooled before adding to the RT-qPCR reaction. | 91.8% (false negatives occurred in samples with Ct >30) [36] | Faster than extraction (~163 min total); but heat treatment can reduce sensitivity for low viral loads, increasing Ct values by 4.5-6 cycles [9] [36]. |

| Direct with RNase Inhibitor [9] | Adding an RNase inhibitor directly to the reaction mix without lysis or heating. | Not fully quantified, but detected ~10 fold less virus than indirect methods [9] | Simple approach that reduces sample handling and improves detection over plain direct methods [9]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for establishing robust RT-qPCR workflows for SARS-CoV-2 detection.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RT-qPCR Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Automated RNA Extraction Kits | Purification of viral RNA from clinical samples, removing inhibitors. | Kits based on magnetic silica particles (e.g., Seegene STARMag, Qiagen EZ1, MagMAX, MAGABIO) are standard for automation [9] [33] [35]. |

| One-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix | Enables combined reverse transcription and PCR amplification in a single tube, reducing hands-on time. | Contains reverse transcriptase, thermostable DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer. Kits from BGI, Norgen, and Seegene are commonly used [9] [37]. |

| TaqMan Probes & Primers | Provide high specificity for target detection in multiplex assays by using a fluorescently labeled probe. | Target SARS-CoV-2 genes like N, E, S, and RdRp. CDC-approved N1/N2 primers are widely implemented [9] [33]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | A cost-effective fluorescent dye that binds double-stranded DNA, used primarily in two-step methods. | Requires post-amplification melt curve analysis to confirm reaction specificity [9] [37]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Used to generate standard curves for absolute quantification, ensuring reproducibility and comparability across labs. | Can be plasmid DNA, synthetic RNA (e.g., from CODEX, JRC), or inactivated virus. Choice of standard significantly impacts absolute quantification [38]. |

| Internal Process Controls | Monitor nucleic acid extraction efficiency and detect PCR inhibition in each sample. | A non-competitive control (e.g., mengovirus) spiked into the sample lysis buffer is recommended [38]. |

Workflow Visualization and Data Analysis

High-Throughput RT-qPCR Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and pathways in a high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 testing pipeline, integrating the methods discussed above.

Critical Data Analysis Considerations

For relative quantification of gene expression, the comparative C_T method (2^−ΔΔCt) is widely used [39]. This method relies on the accurate determination of the cycle threshold (Ct), the point at which fluorescence crosses a defined threshold. Key statistical considerations include [40]:

- Data Quality Control: Ensuring high and consistent PCR amplification efficiency for both target and reference genes is critical for valid results.

- Confidence Intervals and P-values: Proper statistical treatment, including confidence intervals and significance testing, is essential to avoid false positive conclusions, especially in clinical applications.

- Standard Curve Validation: For absolute quantification, the choice of standard material (e.g., plasmid DNA vs. synthetic RNA) can significantly impact the reported copy numbers, highlighting the need for harmonization in reporting [38].

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the critical need for accurate, rapid, and accessible diagnostic testing, particularly in settings with limited laboratory infrastructure and trained personnel. Molecular diagnostics, especially reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), remain the gold standard for SARS-CoV-2 detection due to high sensitivity and specificity [16] [41]. However, their reliance on specialized equipment, lengthy processing times, and high costs have driven the development and adoption of alternative diagnostic platforms suitable for point-of-care (POC) and resource-limited environments [16] [42]. Among the most prominent are reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) and rapid antigen tests (RATs). This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two technologies, focusing on their performance characteristics, operational requirements, and suitability for different testing scenarios within a framework of comparative molecular method analysis.

Fundamental Principles

RT-LAMP is a nucleic acid amplification technique that amplifies target RNA at a constant temperature (typically 60–65°C), eliminating the need for thermal cyclers. It utilizes 4-6 primers targeting 6-8 distinct regions of the viral genome, which confers high specificity. Amplification can be detected in real-time via turbidity or fluorescence, or as an endpoint measurement using colorimetric indicators [41] [43]. Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) are lateral flow immunoassays that detect the presence of specific viral surface proteins, such as the nucleocapsid protein. They typically provide results within 15-30 minutes by producing a visual band on a test strip when viral antigens are present in the sample above a certain threshold [44] [45].

Comprehensive Performance Metrics

Table 1: Direct Comparison of RT-LAMP and Rapid Antigen Tests

| Performance Parameter | RT-LAMP | Rapid Antigen Test (RAT) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Target | Viral RNA | Viral Protein (e.g., Nucleocapsid) |

| Assay Time | 30-60 minutes [41] [46] | 15-30 minutes [44] [42] |

| Sensitivity (Overall) | 85.9% - 92.91% [46] [47] | ~67% [44] |

| Specificity (Overall) | 98.33% - 99.5% [46] [47] | ~75% [44] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | ~6.7 copies/reaction [16] | ≈ 5.0 × 10² pfu/mL (WHO benchmark) [45] |

| Sensitivity in High Viral Load | ~100% (Ct ≤25) [16] [46] | 100% (Ct ≤20) [44] |

| Sensitivity in Low Viral Load | Decreases after 9-10 days post-symptom onset [16] | 22% (Ct >26) [44] |

| Key Advantage | High sensitivity approaching RT-qPCR, isothermal conditions | Speed, low cost, extreme ease of use |

| Main Limitation | Requires precise primer design and sample prep | Significantly lower sensitivity, especially in asymptomatic cases |

The data reveal a clear performance trade-off. RT-LAMP offers diagnostic accuracy much closer to RT-qPCR, particularly during the acute phase of infection (up to 9 days post-symptom onset), where it demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity compared to RT-qPCR [16]. Its performance, however, can depend on the sample processing method, with RNA-extracted samples (RNA-LAMP) showing superior sensitivity (92.91%) compared to direct LAMP protocols (70.92%) [41] [47].

In contrast, RATs provide a speed and convenience advantage but at the cost of significantly lower sensitivity, particularly in patients with lower viral loads. Their sensitivity is highly dependent on viral load, dropping from 100% at Ct values ≤20 to 63% at Ct values 21-25, and as low as 22% at Ct values above 26 [44]. This makes them less effective for detecting pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic infections.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Typical RT-LAMP Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for a colorimetric RT-LAMP assay, commonly used for its simplicity and suitability for point-of-care settings.

Diagram 1: Workflow for a colorimetric RT-LAMP assay. The sample preparation step offers two common paths: RNA extraction for higher sensitivity or direct heat inactivation for speed and simplicity.

A standard RT-LAMP protocol, as detailed in [41] and [47], involves the following steps:

- Sample Collection: Nasopharyngeal swabs are collected and placed in a viral transport medium or a specific preservation solution.

- Sample Processing: Two main approaches are used:

- RNA Extraction: Purified viral RNA is extracted using commercial magnetic bead-based kits (e.g., Jiangsu Bioperfectus Technologies nucleic acid extraction kit) to remove inhibitors and increase test sensitivity [41] [47].

- Direct Method: The original sample is heat-inactivated at 95°C for 5 minutes to lyse the virus and inactivate nucleases, then centrifuged. The supernatant is used directly. This method is faster but may yield lower sensitivity [41] [47].

- Amplification Reaction: A 25μL reaction mixture is prepared containing the processed sample and a master mix with primers, DNA polymerase with reverse transcriptase activity, buffers, and dNTPs. For colorimetric detection, a pH-sensitive dye is also included.

- Incubation: The reaction tube is incubated at a constant temperature of 62–65°C for 30–35 minutes in a dry bath or heat block.

- Result Interpretation: A color change from pink to yellow indicates a positive result due to acidification of the reaction mixture. No color change indicates a negative result. Results can be read visually or with a portable spectrophotometer [41] [46].

Typical Rapid Antigen Test Workflow

The following diagram outlines the standard procedure for a typical rapid antigen test, highlighting its simplicity and rapid turnaround.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a typical Rapid Antigen Test (RAT). The process is designed for minimal steps and user-friendly visual interpretation.

A standard RAT protocol, as described in [44] and [47], is as follows:

- Sample Collection: A nasopharyngeal swab is collected from the patient.

- Sample Elution: The swab is inserted into a tube containing a proprietary extraction buffer and rotated vigorously against the tube's inner wall to elute viral proteins.

- Test Application: After waiting approximately one minute, 3-4 drops (around 80μL) of the extracted solution are dispensed into the sample well of the test cassette.

- Lateral Flow and Incubation: The solution migrates across the test strip via capillary action.

- Result Interpretation: Results are read within 15-20 minutes. The appearance of both a control line and a test line indicates a positive result. The appearance of only the control line indicates a negative result. The absence of a control line renders the test invalid [44] [47].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Selecting the appropriate reagents and materials is fundamental to the successful implementation of either diagnostic platform.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Kits/Catalogs (from search results) |

|---|---|---|

| RT-LAMP Primers/Master Mix | Pre-mixed solutions containing primers, polymerase, buffers, and dNTPs for isothermal amplification. | Loopamp SARS-CoV-2 Detection Kit (Eiken Chemical) [16], Shanghai GeneSc Biotech Kit [41] [47] |

| Viral RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies viral RNA from clinical samples to remove PCR inhibitors and increase assay sensitivity. | QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) [16] [47], Nucleic Acid Extraction Rapid Kit (Magnetic Bead Method) [41] [47] |

| Colorimetric Detection Additive | A pH-sensitive dye that causes a visible color change (e.g., pink to yellow) upon amplification. | Included in commercial RT-LAMP kits like the GeneSc Biotech kit [41] |

| Rapid Antigen Test Cassette | A lateral flow immunoassay device that detects SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. | PCL Spit Rapid Antigen Test Kit [44], Panbio COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test [48], BTNX Rapid Response [48] |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | A medium used to preserve virus viability and nucleic acid integrity during swab transport. | BD Universal Viral Transport Medium [16], Universal Transport Media (UTM) [48] |

| Isothermal Heat Block | A device to maintain a constant temperature (60-65°C) required for the RT-LAMP reaction. | Standard dry bath or heat block [41] |

Choosing the Right Tool for the Objective

The choice between RT-LAMP and RATs is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of matching the technology to the specific public health or clinical objective, available resources, and stage of infection.

RT-LAMP is the superior choice when the testing goal is high diagnostic accuracy in a decentralized setting. Its performance is closest to RT-qPCR, making it suitable for confirming symptomatic cases in clinics, testing high-risk contacts, and situations where a false negative carries significant risk [42]. It is particularly effective during the early symptomatic phase (first 7-9 days) when the viral load is high [16] [41]. While more complex than RATs, it is far less resource-intensive than lab-based RT-qPCR.

Rapid Antigen Tests are optimal for the purpose of frequent, widespread screening to quickly identify and isolate highly infectious individuals. Their speed, low cost, and simplicity make them ideal for screening programs in schools, workplaces, and before large gatherings [42] [45]. They are most effective in individuals with high viral loads, who are also the most likely to be contagious. Their lower sensitivity is a recognized trade-off for their role in breaking chains of transmission through rapid identification of the most infectious cases [44] [42].

Cost-Effectiveness and Modeling Insights

Mathematical modeling underscores that testing frequency and turnaround time can be more critical than raw test sensitivity for epidemic control [42]. In this context, the low cost and speed of RATs make them highly effective for frequent population screening. One cost-effectiveness analysis of surveillance strategies found that direct testing approaches (similar to how RATs are often deployed) were more cost-effective than complex, pre-screened strategies, with costs per sample tested around €53 for direct household testing [49].

Within the comparative framework of molecular methods for SARS-CoV-2 research and diagnostics, both RT-LAMP and rapid antigen tests have cemented their roles. RT-LAMP serves as a powerful accuracy-oriented POC tool, bridging the gap between lab-based gold standards and field deployment. In contrast, rapid antigen tests are public-health-oriented screening tools, sacrificing some sensitivity for unprecedented speed, scalability, and accessibility. Future research and development will continue to optimize these technologies, but their complementary strengths will remain essential for building resilient and responsive global diagnostic networks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the critical importance of genomic surveillance in understanding and controlling the spread of viral pathogens. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have been at the forefront of this effort, enabling researchers to track SARS-CoV-2 transmission routes, monitor the emergence of novel variants, and inform public health responses [50]. Several NGS protocols and platforms have been developed for whole genome sequencing (WGS) of SARS-CoV-2, each with distinct advantages and limitations in terms of cost, throughput, accuracy, and scalability. This guide provides an objective comparison of the leading NGS methodologies and platforms used in SARS-CoV-2 research, supported by experimental data from comparative studies, to assist researchers and public health professionals in selecting appropriate tools for variant surveillance and outbreak investigation.

Table 1: Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing Methods

| Method | Best For | Accuracy & Coverage | Cost & Scalability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplicon (ARTIC, Midnight) | Population-scale surveillance, low viral load samples [51] | Good genome coverage (>94% with Illumina), sensitive for low Ct samples [51] [52] | Cost-effective, highly scalable, suitable for clinical environments [51] [52] | Primer mismatches with new variants can cause amplicon dropouts [52] |

| Amplicon (Illumina COVIDSeq) | Cost-effective production of consensus sequences [51] | High performance for consensus sequence generation [51] | Most cost-effective among tested methods [51] | Protocol optimized for specific sample types (nasopharyngeal swabs) [51] |

| Hybrid Capture (Twist) | Identifying novel variants, mutation detection across genome [52] | Superior coverage uniformity, better tolerance to mismatches (~10-20%) [52] | Higher cost, more laborious workflow, batch variation [52] | High human host contamination, requires more RNA input [52] |

| Metagenomic Shotgun | Novel pathogen discovery, comprehensive pathogen profiling [50] | Effective when viral abundance is high [51] | No prior knowledge of organisms needed [50] | Lacks sensitivity for low viral load clinical samples [51] |