Comparative Viral Infectivity Testing In Vitro: Methods, Applications, and Advancements for Drug Development

In vitro viral infectivity testing is a cornerstone of virology, antiviral drug development, and vaccine efficacy studies.

Comparative Viral Infectivity Testing In Vitro: Methods, Applications, and Advancements for Drug Development

Abstract

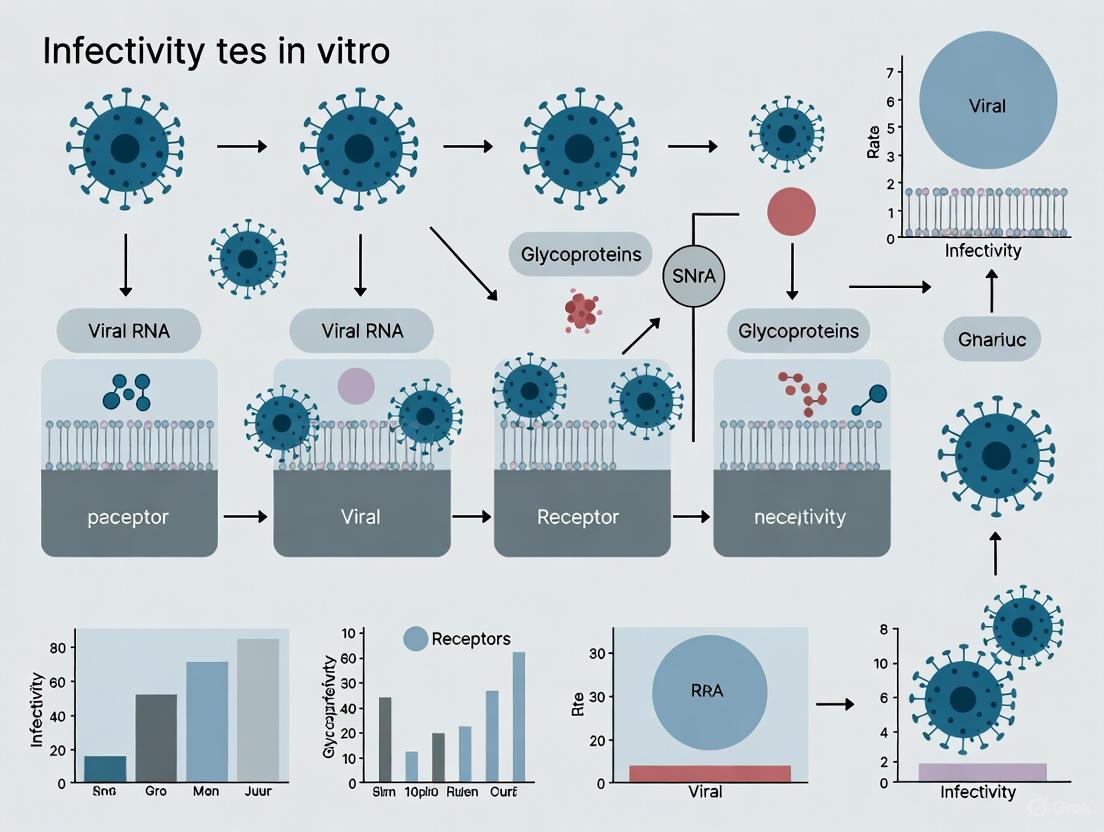

In vitro viral infectivity testing is a cornerstone of virology, antiviral drug development, and vaccine efficacy studies. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the established and emerging methodologies used to quantify and compare viral infectivity. We explore foundational principles, including the critical distinction between detecting viral components and measuring functional infectivity. A detailed comparison of methodological approaches—from traditional plaque and TCID50 assays to modern flow cytometry and label-free technologies—is presented, alongside protocols for critical applications like neutralization testing. The content further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies to enhance assay robustness and reproducibility. Finally, we discuss validation frameworks per global regulatory standards (ICH Q5A(R2), FDA, EMA, China CDE) and the strategic selection of methods for comparative studies, illustrated with case studies from recent research on SARS-CoV-2, LCMV, and viral vectors for gene therapy.

Viral Infectivity Fundamentals: From Viral Lifecycle to Quantitative Measurement

Contents

- Key Concepts and Definitions

- Comparative Methods for Quantifying Viral Infectivity

- Advanced Concepts: Collective Infectious Units

- Experimental Workflows

- Research Reagent Solutions

Key Concepts and Definitions

Viral infectivity is fundamentally defined as the ability of a virus to enter a host cell, replicate within it, and spread to new cells [1]. However, a critical challenge in virology is that not all virus particles are infectious. This distinction separates the mere presence of viral components (like proteins or nucleic acids) from the actual functional capacity to cause an infection. The gold standard for measuring infectivity relies on functional assays that demonstrate a virus's ability to complete its replication cycle in a susceptible cell culture system [2] [3].

A core principle for understanding this distinction is the particle-to-PFU ratio. This ratio compares the total number of physical virus particles in a sample (often determined by methods like electron microscopy or quantitative PCR) to the number of particles capable of forming a plaque—a Plaque-Forming Unit (PFU) [4]. A ratio of 1, as seen in some bacteriophages, indicates that every physical particle is infectious. In contrast, for many animal viruses, this ratio can be much higher.

Table 1: Representative Particle-to-PFU Ratios for Different Viruses

| Virus | Typical Particle-to-PFU Ratio | Implication for Infectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage (e.g., T4) | ~1 [4] | Nearly every viral particle is infectious. |

| Poliovirus | >1000 (can be very high) [4] | A very small fraction of particles initiate a productive infection. |

| Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) | Varies; aggregation can increase co-infection [5] | Infectivity is influenced by factors like virion aggregation. |

High particle-to-PFU ratios can arise from several factors. Many particles may contain lethal mutations in their genomes or may have been damaged during purification. Furthermore, the infectious cycle is complex, and a particle may fail at any step—from entry and uncoating to genome replication and assembly—preventing the completion of an infectious cycle [4]. This highlights that detecting viral RNA or proteins (e.g., via PCR or ELISA) does not equate to detecting infectious virus, a distinction crucial for diagnostics and public health policies [6].

Comparative Methods for Quantifying Viral Infectivity

Different assays provide varying information about viral infectivity, each with its own advantages and limitations. The following table summarizes key methods used in quantitative comparisons.

Table 2: Key Assays for Quantifying Viral Infectivity and Components

| Assay Name | What is Measured? | Principle | Output Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque Assay [2] | Infectious Units (PFU/mL) | Serial dilutions of virus are applied to a cell monolayer. After incubation, plaques (clear zones of lysed cells) are counted. | Quantitative titer of infectious virus (PFU/mL). |

| TCID50 Assay [3] | Infectious Dose (Tissue Culture Infectious Dose 50%) | Serial dilutions of virus are applied to cells and observed for cytopathic effect (CPE). The dilution that infects 50% of the cultures is calculated. | Quantitative titer of infectious virus (TCID50/mL). |

| PCR / qRT-PCR [2] | Viral Genome Copies | Amplification of specific viral nucleic acid sequences. Does not distinguish between infectious and non-infectious particles. | Quantitative number of genome copies per volume. |

| ELISA [2] | Viral Antigens | Detection of viral proteins using specific antibodies. Does not distinguish between infectious and non-infectious particles. | Semi-quantitative or quantitative measure of viral protein. |

| Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA) [2] | Viral Proteins in Infected Cells | Fixed cells are stained with fluorescently tagged antibodies against viral antigens and visualized by microscopy. | Qualitative/Quantitative detection of infection in cells. |

| Hemagglutination Assay [2] | Viral Particles Capable of Agglutinating RBCs | Some viruses can bind to and cross-link red blood cells (RBCs). The titer is the highest dilution that causes agglutination. | Quantitative measure of virus particles with functional surface proteins. |

Advanced Concepts: Collective Infectious Units

The traditional model of viral spread involves independent virions. However, growing evidence shows that viruses often spread via collective infectious units, structures that simultaneously deliver multiple viral genomes to a cell [5]. This increases the multiplicity of infection (MOI) independently of viral population density and has profound implications for viral evolution, including the maintenance of genetic diversity and the evolution of social-like interactions such as cooperation and complementation [5].

The main types of collective infectious units include:

- Polyploid Virions: Some virions naturally contain multiple genome copies. Retroviruses are pseudo-diploid, and some paramyxoviruses (e.g., measles) and filoviruses (e.g., Ebola) can package multiple genomes [5] [3].

- Virion Aggregates: Viral particles can form aggregates, often promoted by body fluids like saliva or by non-neutralizing antibodies. These aggregates are transmitted as a single infectious unit, facilitating co-infection [5] [7].

- Virion-Containing Lipid Vesicles: Enteroviruses and other viruses can be released from cells enclosed within lipid microvesicles. These vesicles protect the virions and enable the co-transmission of multiple genomes to a new cell [5] [6].

- Virus-Induced Cell-Cell Structures: Viruses like HIV can induce the formation of virological synapses, which are specialized cell-cell contacts that allow for the direct cell-to-cell transfer of viral progeny, efficiently delivering a high number of virions [5].

Experimental Workflows

A standard workflow for quantifying viral infectivity begins with cell culture, as viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that require living cells to replicate [2]. The following diagram outlines the key steps from generating a virus stock to determining its infectious titer.

Detailed Protocol: Plaque Assay for Infectivity Titer Determination

The plaque assay is a fundamental method for quantifying infectious virus. Below is a generalized protocol that can be adapted for specific viruses.

- Cell Seeding: Seed permissive cells into a multi-well plate (e.g., 6-well or 96-well) to form a confluent monolayer. Allow cells to adhere overnight [2] [3].

- Virus Inoculation:

- Prepare serial log10 dilutions (e.g., 10-1 to 10-8) of the virus stock in an appropriate dilution buffer (e.g., serum-free maintenance medium).

- Remove the growth medium from the cell monolayers and wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Carefully add the virus dilutions to the respective wells. Gently rock the plate to ensure even distribution.

- Incubate the plate at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 37°C for mammalian viruses) for a defined adsorption period (e.g., 1-2 hours), with occasional rocking.

- Overlay and Incubation:

- After adsorption, remove the virus inoculum.

- Overlay the cell monolayer with a semi-solid medium (e.g., carboxymethylcellulose, agarose, or methylcellulose) mixed with maintenance medium. This restricts released virions to infecting only neighboring cells, leading to the formation of discrete plaques.

- Incubate the plates for the required time (typically 2-7 days, depending on the virus) until plaques become visible.

- Plaque Visualization and Counting:

- Plaques can be visualized by various methods:

- Direct Microscopy: Some plaques are visible as clear areas against the confluent cell layer.

- Staining: Fix cells with formaldehyde and stain with crystal violet or neutral red. Live cells take up the stain, while plaques remain clear [2].

- Count plaques in wells that have a countable number (ideally 20-100 plaques). Calculate the viral titer using the formula:

- PFU/mL = (Number of plaques) / (Dilution factor × Volume of inoculum (mL))

- Plaques can be visualized by various methods:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful viral infectivity testing relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential materials and their functions in a research context.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Viral Infectivity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Viral Infectivity Research |

|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems (Primary, Immortalized, or Designer Cells) [2] | Provides the necessary living host cells for virus replication. Cell type must express appropriate viral receptors and internal machinery. |

| Maintenance and Growth Media [2] | Supplies nutrients and optimal conditions (pH, osmolarity) to sustain cell health and support viral replication. |

| Semi-Solid Overlay (e.g., Carboxymethylcellulose, Agarose) [2] | Restricts virus diffusion in plaque assays, enabling the formation of discrete, countable plaques. |

| Fixatives and Stains (e.g., Formaldehyde, Crystal Violet) [2] | Used to fix cells and stain the cell monolayer for clear visualization of plaques against a contrasting background. |

| Specific Antibodies (for IFA, ELISA) [2] | Enables detection and localization of viral antigens within infected cells (IFA) or quantification in a sample (ELISA). |

| Fluorescent Tags (e.g., GFP, Alexa Dyes) [2] | Allows direct visualization of viral proteins or tracking of infection progress through live or fixed cell microscopy. |

| Protease (Trypsin) and Collagenase [2] | Enzymes used to dissociate tissues for generating primary cell cultures (collagenase) or to passage adherent cells (trypsin). |

| Centrifugation Equipment (Ultracentrifuges) [2] | Essential for purifying and concentrating virus particles away from cellular debris and media components. |

| PCR/qPCR Reagents and Primers [2] | For highly sensitive detection and quantification of viral genome copies, though it does not indicate infectivity. |

The Viral Lifecycle as a Framework for Infectivity Assays

Viral infectivity assays are fundamental tools in virology, providing critical data on viral replication kinetics, antiviral drug efficacy, and neutralizing antibody responses. The selection of an appropriate infectivity assay is profoundly influenced by the specific stage of the viral lifecycle it targets, from initial entry to the final stages of progeny release and cell death. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary viral infectivity assay technologies, evaluating their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and applications within the framework of the viral lifecycle. We present structured experimental data and detailed protocols to assist researchers in selecting optimal methodologies for their specific investigative needs in antiviral development and basic virology research.

Assay Technology Comparison

Modern viral infectivity assays can be broadly categorized based on their detection principle, throughput, and the specific lifecycle stage they monitor. The following table summarizes the key technologies currently employed in research settings.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Viral Infectivity Assay Technologies

| Assay Technology | Lifecycle Stage Targeted | Throughput | Time to Result | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque Assay (PFU) [8] | Late (CPE) | Low | 3-7 days | Direct quantification of infectious units; considered a gold standard | Low throughput; subjective manual counting; lengthy process |

| Endpoint Dilution (TCID₅₀) [9] | Late (CPE) | Medium | 3-7 days | Does not require overlay; can handle viruses that don't form clear plaques | Statistical rather than direct count; lower precision |

| Focus Forming Unit (FFU) [8] | Intermediate (Antigen Expression) | Low | 2-3 days | Detects infected foci before full CPE; uses immunostaining | Requires specific antibodies; additional staining steps |

| AI-Powered Imaging (DVICE) [10] [11] | Late (CPE) / Morphology | High | 1-7 days (real-time possible) | Label-free; high-throughput; objective; virus-specific feature recognition | Requires initial training dataset; model transferability challenges |

| Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) [12] | Late (CPE) / Cell Viability | High | Minutes to Days | Label-free, real-time kinetic data; continuous monitoring | Indirect measure of infectivity; specialized equipment required |

| Luciferase Reporter Assay [13] | Early (Entry/Replication) | High | 1-2 days | Highly sensitive; measures early infection events | Requires engineered reporter viruses; not suitable for clinical isolates |

| Fluorescence Microscopy [12] | Intermediate (Antigen Expression) | Medium | 1-3 days | Direct visualization of infection; can be quantitative | Requires fluorescent tags or antibodies; imaging analysis needed |

Quantitative Performance Data

The quantitative output of an infectivity assay is a critical performance metric. Data from recent studies demonstrate the sensitivity and dynamic range of various methodologies.

Table 2: Experimental Antiviral Efficacy Data from Recent Studies

| Antiviral Compound / Technology | Virus Tested | Assay Type | Key Quantitative Result | Cell Line Used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymol | Influenza A/H1N1 | Crystal Violet (IC₅₀) | IC₅₀ = 0.022 µg/mL | MDCK | [9] |

| Limonin | Influenza A/H1N1 | Crystal Violet (IC₅₀) | IC₅₀ = 4.25 µg/mL | MDCK | [9] |

| Thymol | SARS-CoV-2 | Crystal Violet (IC₅₀) | IC₅₀ = 0.591 µg/mL | Vero E6 | [9] |

| Limonin | SARS-CoV-2 | Crystal Violet (IC₅₀) | IC₅₀ = 4.04 µg/mL | Vero E6 | [9] |

| GW4064 (FXR agonist) | HEV | Novel in vitro multi-infection | 85-95% reduction in intracellular HEV RNA | dHuH7.5-NTCP | [14] |

| Sofosbuvir | HCV & HEV | Novel in vitro multi-infection | >90% reduction in viral RNAs | dHuH7.5-NTCP | [14] |

| Interferon-α | HCV, HEV, HDV | Novel in vitro multi-infection | 80% reduction in intracellular viral RNAs | dHuH7.5-NTCP | [14] |

| DVICE (AI Model) | SARS-CoV-2, IAV, AdV, etc. | AI-based CPE detection | AUROC = 0.991 ± 0.001 vs. human annotation | Multiple cell lines | [10] [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Automated Plaque Assay Protocol

The automated plaque assay enhances the traditional method by incorporating imaging and analysis to reduce subjectivity. The following workflow visualizes the key stages.

Diagram 1: Automated Plaque Assay Workflow. PFU: Plaque-forming Unit.

Key Steps:

- Cell Seeding: Seed permissive cells (e.g., Vero CCL-81, BHK CCL-10) to form confluent monolayers in multi-well plates (6- to 96-well format) [12] [8].

- Virus Inoculation: Inoculate with 10-fold serial dilutions of virus stock. Adsorb for 1 hour at 37°C with gentle rocking [8].

- Overlay: Replace medium with a semi-solid overlay (e.g., 0.2-0.8% agarose or carboxymethyl cellulose) to restrict viral diffusion and ensure discrete plaque formation [8].

- Incubation: Incubate for 3-7 days (duration is virus-dependent) at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [8].

- Staining and Imaging: Remove overlay, fix cells with ice-cold methanol/acetone (1:1), and stain with 0.1% crystal violet. Alternatively, for focus-forming assays, immunostain with virus-specific antibodies (e.g., 4G2 for orthoflaviviruses) [8]. Image entire wells using an automated imager like the Agilent BioTek Cytation [12].

- Analysis: Use integrated software (e.g., Gen5) to automatically count plaques or foci based on size and contrast, then calculate the titer in PFU/mL or FFU/mL [12] [8].

AI-Powered CPE Detection (DVICE) Protocol

The Detection of Virus-Induced Cytopathic Effect (DVICE) pipeline uses machine learning to automate infection scoring from label-free images.

Diagram 2: AI-Powered CPE Detection Workflow. CPE: Cytopathic Effect, CNN: Convolutional Neural Network.

Key Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Seed ~10,000 permissive cells per well in a 96-well plate. Infect with virus serial dilutions and incubate for up to 7 days to allow CPE manifestation [10] [11].

- Image Acquisition: Acquire transmitted-light microscopy images using a high-throughput microscope (e.g., ImageXpress Micro Confocal) with a 4x objective. One central site per well is typically imaged [10].

- Ground Truth Generation: Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde and stain with 0.25% crystal violet. Have multiple human experts independently annotate the infection status of each well to create a ground truth dataset [11].

- Model Training: Train a convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the EfficientNet-B0 architecture using the transmitted-light images and their corresponding labels. The dataset used in the original study comprised 58,619 images (22,873 infected, 35,746 uninfected) across multiple viruses and cell lines [10] [11].

- Validation and Deployment: Validate the model using leave-one-out cross-validation. The published DVICE model achieved an AUROC of 0.991 ± 0.001. Apply the trained model to classify new images and calculate infectivity scores or TCID₅₀ values [11].

Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA) Protocol

The xCELLigence RTCA system continuously monitors cell status via electrical impedance, providing real-time, label-free data on CPE development.

Key Steps:

- Cell Seeding and Baseline Monitoring: Seed cells onto specialized E-Plates. Monitor cell index (a measure of impedance) for 12-24 hours to establish a baseline and confirm cell health and appropriate seeding density [12].

- Virus Inoculation and Continuous Monitoring: Inoculate cells with virus. Continue to monitor cell index impedance in real-time. Virus-induced CPE causes cells to detach, resulting in a quantifiable decrease in cell index [12].

- Data Analysis: Analyze the kinetic data to determine the time-point of CPE initiation, the rate of CPE progression, and the final degree of destruction. This data can be used to calculate viral titer or evaluate antiviral compound efficacy [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of viral infectivity assays requires specific reagents and instrumentation. The following table details key solutions for setting up these experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Infectivity Assays

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Permissive Cell Lines | Support viral replication and CPE development. Critical for assay sensitivity. | Vero CCL-81, Vero E6, BHK CCL-10, MDCK, A549, Huh7 [10] [9] [8] |

| Semi-Solid Overlays | Restrict virus spread to enable plaque formation in plaque assays. | 0.2-0.8% Agarose, Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) [8] |

| Detection Antibodies | Enable immunodetection of viral antigens in FFU assays. | Pan-orthoflavivirus 4G2 monoclonal antibody [8] |

| Vital Stains | Visualize cell viability and plaque formation in endpoint assays. | Crystal Violet (0.1-0.25%), Neutral Red [10] [9] [8] |

| Fixatives | Preserve cell morphology and inactivate virus for safe staining. | Methanol/Acetone (1:1), 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) [10] [8] |

| Automated Imaging Systems | Acquire high-throughput, high-content image data for analysis. | Agilent BioTek Cytation series, ImageXpress Micro Confocal (IXM-C) [10] [12] |

| Real-Time Cell Analyzers | Generate label-free, kinetic data on cell health and CPE. | Agilent xCELLigence RTCA systems [12] |

| AI/Image Analysis Software | Automate plaque counting and infection classification. | ViQi AVIA, Gen5 Software, DVICE (EfficientNet-B0 CNN) [10] [11] [12] |

The landscape of viral infectivity testing is evolving from traditional, low-throughput methods toward automated, kinetic, and information-rich platforms. The choice of assay must align with the research question, considering whether the target is early replication events or late-stage cytopathic effects. While plaque and TCID₅₀ assays remain gold standards for direct quantification, AI-powered imaging and real-time impedance technologies offer compelling advantages in throughput, objectivity, and kinetic resolution. The integration of these advanced platforms, supported by robust experimental protocols and reagents, is accelerating the pace of virology research and antiviral discovery.

The accurate quantification of infectious virus particles is a cornerstone of virology, critical for diagnostics, vaccine development, antiviral evaluation, and understanding viral pathogenesis [15]. Among the various techniques available, two cell-based methods stand as fundamental tools for determining the concentration of replication-competent virions: the plaque assay and the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay. The plaque assay is widely regarded as the gold standard for directly quantifying lytic virions, providing a direct count of infectious units [15] [16]. In contrast, the TCID50 assay employs an endpoint dilution approach to determine the dilution at which 50% of inoculated cell cultures become infected, providing an indirect estimate of infectious titer through statistical calculation [16] [17]. These techniques differ not only in their methodology but also in their underlying mathematical principles, applications, and the interpretation of their results. Understanding the key principles, comparative performance, and appropriate contexts for employing each method is essential for researchers and drug development professionals working in virology and related fields. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these fundamental quantification methods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform their application in contemporary viral research.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Principles

Plaque Assay: Direct Quantification of Infectious Units

The plaque assay operates on the principle that each plaque observed in a cell monolayer represents the infectious activity of a single virion [16]. This one-to-one correspondence makes it a direct measure of infectious virus particles. Technically, the method involves preparing serial dilutions of a virus sample, inoculating susceptible cell monolayers, and then overlaying the cells with a semi-solid medium (such as agarose or carboxymethyl cellulose) that restricts viral spread to neighboring cells, thereby creating discrete zones of infection known as plaques [15] [16]. After an appropriate incubation period, plaques are counted manually or through automated imaging systems. The calculation of the viral titer follows this formula:

IU/ml = Number of plaques / (dilution factor × inoculated volume in ml) [16]

For example, if 32 plaques are counted at the 10⁻³ dilution from an inoculated volume of 0.5 ml, the titer would be calculated as: 32 / (10⁻³ × 0.5) = 6.4 × 10⁵ IU/ml [16]. This direct counting method provides a precise measurement of plaque-forming units (PFU) per milliliter, with the term "infectious units" (IU) often used interchangeably with PFU.

TCID50 Assay: Endpoint Dilution and Statistical Estimation

The TCID50 assay employs a fundamentally different approach based on binary response (presence or absence of infection) across multiple replicate wells at different dilutions to statistically determine the dilution at which 50% of the cultures become infected [16] [17]. Unlike the plaque assay, it does not involve a semi-solid overlay, allowing unconstrained viral spread in liquid medium, with infection typically assessed through visual observation of cytopathic effect (CPE) [15] [17]. The core probabilistic assumption is that at the dilution where only 50% of wells show infection, there is, on average, one infectious particle per well, as this scenario presents a 50% probability of infection occurring [16]. The mathematical foundation relies on the Poisson distribution, which models the probability of a cell culture being infected when a random number of virus particles are distributed across multiple cultures [18].

Two primary statistical methods are used to calculate the TCID50 titer:

Reed-Muench Method: This cumulative approach involves scoring positive and negative wells across dilutions, calculating cumulative sums, determining infection rates, identifying the 50% endpoint, and calculating a proportionate distance to interpolate the exact endpoint [16]. The formula is: Log(TCID50) = log(dilution above 50%) + (-proportionate distance) × log(dilution factor) [16]

Spearman-Kärber Method: This simpler method requires only the total number of positive wells across all dilutions and uses the formula: Log(TCID50) = log(lowest dilution with 100% CPE) + I × [0.5 - (total CPE wells/total replicates)] where I is the log of the dilution factor [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Calculation Methods for TCID50 Assay

| Feature | Reed-Muench Method | Spearman-Kärber Method |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity | More complex, multiple steps | Simpler, fewer calculation steps |

| Data Visualization | Provides clearer infection dynamics across dilutions | Relies on total infected wells |

| Assumption | Fewer assumptions about distribution pattern | Assumes progressive decrease in infected wells with dilution |

| Regulatory Preference | Sometimes preferred for detailed analysis | Often acceptable, depending on specific guidelines |

Mathematical Relationship and Unit Conversion

A critical relationship exists between TCID50 and PFU measurements, derived from Poisson distribution principles. At the 50% infection point (TCID50), the probability of no infection P(0) = 0.5 [18]. According to Poisson distribution:

P(0) = e^(-IU) where IU represents infectious units [18]

Substituting P(0) = 0.5 gives: 0.5 = e^(-IU) Solving for IU: IU = -ln(0.5) ≈ 0.693 [18]

This establishes the fundamental conversion factor: 1 TCID50 ≈ 0.7 PFU or 1 PFU ≈ 1.44 TCID50 [18]

Therefore, to convert a TCID50/ml titer to PFU/ml, multiply by 0.7: PFU/ml = TCID50/ml × 0.7 [18]

This mathematical relationship allows researchers to compare results across studies using different quantification methods and is essential for meta-analyses and standardized reporting in virology.

Comparative Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Direct Comparative Studies of PFU and TCID50 Assays

Experimental comparisons between PFU and TCID50 assays reveal important differences in their performance characteristics and outputs. A 2022 study systematically compared these methods across several SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the D614G strain (B.1), three Variants of Concern (Alpha, Gamma, Delta), and one Variant of Interest (Mu) [15]. The plaque assay reported viral titers between 0.15 ± 0.01×10⁷ and 1.95 ± 0.09×10⁷ PFU/mL, while the TCID50 assay yielded titers between 0.71 ± 0.01×10⁶ to 4.94 ± 0.80×10⁶ TCID50/mL for the same isolates [15]. The calculated PFU/mL from TCID50 assays differed significantly from directly measured PFU/mL for most variants, with log10 differences of 0.61 for Alpha, 0.59 for Gamma, 0.59 for Delta, and 0.96 for Mu variants (p≤0.0007), though no significant difference was observed for the D614G strain [15]. This variant-dependent discrepancy highlights that the relationship between these assays can be influenced by viral characteristics, possibly due to differences in cell entry mechanisms, replication kinetics, or cell-to-cell spread efficiency among variants.

A separate comparison focusing on filoviruses found that the TCID50 assay appeared to be more sensitive but slightly more variable than plaque assays, with approximately a tenfold difference in the numerical results between the methods [19]. This study also noted that both methods remain useful and practicable in filovirus research, with the comparison providing valuable guidance for standardizing approaches across laboratories [19]. The observed variability in TCID50 assays may stem from its reliance on categorical scoring of CPE rather than direct counting of discrete events, introducing more subjectivity into the measurement process.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of PFU and TCID50 Titers Across SARS-CoV-2 Variants [15]

| SARS-CoV-2 Variant | Plaque Assay (PFU/mL) | TCID50 Assay (TCID50/mL) | Log10 Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| D614G (B.1) | Not specified | Not specified | Not significant |

| Alpha (B.1.1.7) | Within study range | Within study range | 0.61 |

| Gamma (P.1) | Within study range | Within study range | 0.59 |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) | Within study range | Within study range | 0.59 |

| Mu (B.1.621) | Within study range | Within study range | 0.96 |

Accuracy, Variability, and Method-Specific Considerations

The precision and reliability of PFU and TCID50 assays have been quantitatively assessed through various studies. Relative errors associated with plaque assays have been estimated at 10–100%, while TCID50 assays have approximately 35% error [17]. This difference in error rates reflects their distinct methodological approaches: the plaque assay's error primarily stems from counting statistics and plaque identification subjectivity, while the TCID50 assay's error derives from the binary scoring system and statistical estimation process.

A study on human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) quantification found that a quantitative PCR (qPCR)-based readout of TCID50 demonstrated substantially lower intra-assay variability (9% coefficient of variation) compared to ocular inspection readout of TCID50 (45% CV) [20]. This suggests that alternative detection methods can significantly improve the reliability of TCID50 assays while maintaining comparable absolute values—1 Q-PCR TCID50 equaled 1.41 ocular TCID50 and 1.03 IFA TCID50 values with no statistical significance [20]. This highlights how the choice of detection method (CPE, IFA, or qPCR) can substantially impact the precision of TCID50 assays without fundamentally altering the calculated titer.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard Plaque Assay Protocol

The plaque assay protocol involves multiple critical steps to ensure accurate quantification:

Cell Culture Preparation: Seed susceptible cell monolayers (e.g., Vero E6 cells for SARS-CoV-2) in appropriate culture vessels and incubate until they reach 80-100% confluency [15] [17]. The specific cell line must be permissive to the virus being quantified.

Viral Dilution Preparation: Prepare serial 10-fold dilutions of the virus sample in suitable maintenance medium or buffer, typically covering a range from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁸ depending on the expected titer [16].

Inoculation: Remove growth medium from cell monolayers and inoculate with predetermined volumes of each viral dilution, typically in duplicate or triplicate. Include control wells without virus [17].

Adsorption: Allow virus adsorption to cells for a specified period (usually 1-2 hours) at 37°C with occasional gentle rocking to ensure even distribution [17].

Overlay Application: Remove inoculum and carefully add semi-solid overlay medium (e.g., carboxymethyl cellulose or agarose) to restrict viral spread to adjacent cells, enabling plaque formation [15] [16].

Incubation: Incubate cells for an appropriate duration (varies by virus, typically 2-7 days) until visible plaques develop [17].

Plaque Visualization: Remove overlay, fix cells, and stain with crystal violet, neutral red, or immunostaining to visualize and count plaques [15] [16].

Calculation: Count plaques in wells with 10-100 discrete plaques and calculate titer using the formula: IU/ml = (number of plaques) / (dilution factor × volume of inoculum in ml) [16].

Standard TCID50 Assay Protocol

The TCID50 assay protocol follows these essential steps:

Cell Seeding: Seed host cells in 48- or 96-well plates at optimal density (e.g., 7×10⁴ cells/ml for 48-well plates) and incubate until 80-90% confluent [17].

Viral Dilution Series: Prepare serial 1:10 dilutions of virus sample in appropriate medium, typically from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁸ or higher [16] [17].

Inoculation: Infect multiple replicate wells per dilution (typically 4-8 replicates) with a fixed volume of each dilution [16] [17]. Include control wells with medium only.

Incubation and Observation: Incubate plates for virus-specific duration (may require 5-20 days for slow-growing viruses) and regularly monitor for cytopathic effect (CPE) [17].

Scoring: Score each well as positive or negative based on CPE presence at predetermined time points [16] [17].

Calculation: Apply Reed-Muench or Spearman-Kärber method to calculate TCID50/ml [16]. For Reed-Muench:

- Calculate cumulative positive and negative wells

- Determine infection rates

- Identify dilutions bracketing 50% infection

- Calculate proportionate distance

- Apply formula: Log(TCID50) = log(dilution above 50%) + (-PD) × log(dilution factor) [16]

Volume Adjustment: Adjust for inoculum volume: TCID50/ml = calculated TCID50 × (1/inoculum volume in ml) [16].

Diagram 1: TCID50 Assay Workflow - This diagram illustrates the sequential steps in a standard TCID50 assay protocol, from cell preparation to final titer determination.

Applications and Method Selection Criteria

Context-Specific Method Applications

The choice between PFU and TCID50 assays depends heavily on the specific research context and viral characteristics:

Plaque Assays are particularly valuable for:

- Vaccine development and evaluation where precise quantification of infectious virus is critical [15]

- Antiviral drug testing that requires accurate measurement of infectious titer reduction [15]

- Purification of viral clones through plaque isolation

- Studies of viral pathogenesis and replication kinetics [15]

- Viruses that form clear, distinct plaques in available cell lines

TCID50 Assays are preferred for:

- Viruses that do not form distinct plaques but still produce observable CPE [17]

- High-throughput applications where 96-well formats offer efficiency advantages

- Situations with limited virus sample availability [17]

- Viruses with long replication cycles where daily monitoring is practical

- Diagnostic virology applications including HIV-1, influenza, and human herpesviruses [17]

Integrated Approach with Molecular Methods

Complementing these traditional infectivity assays, molecular methods like quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) provide additional layers of information but measure different aspects of viral presence. A key distinction is that qRT-PCR quantifies viral RNA copies rather than infectious particles, which can lead to significant discrepancies as not all viral genomes are packaged into infectious virions [15]. Research on SARS-CoV-2 variants demonstrated varying ratios between PFU and RNA copies across variants: 1:29,800 for D614G, 1:11,700 for Alpha, 1:8,930 for Gamma, 1:12,500 for Delta, and 1:2,950 for Mu [15]. This indicates that the proportion of infectious virions changes depending on the viral variant, with Mu variant reaching higher infectious titers with fewer viral copies [15]. This highlights the importance of selecting quantification methods aligned with the specific research question—whether assessing total viral material (qPCR) or replication-competent virus (PFU/TCID50).

Diagram 2: Method Selection Guide - This decision tree illustrates key considerations when choosing between PFU and TCID50 assays for viral quantification, including common application scenarios for each method.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Viral Quantification Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Permissive Cell Lines | Provide susceptible host cells for viral replication | Vero E6 cells (SARS-CoV-2) [15], HSB-2 cells (HHV-6) [20] |

| Semi-Solid Overlay Media | Restrict viral spread for plaque formation | Carboxymethyl cellulose, agarose [16] |

| Cell Culture Media | Support cell viability and viral replication | DMEM, RPMI-1640 with serum supplements [15] [20] |

| Staining Reagents | Visualize plaques or infected cells | Crystal violet, neutral red, immunostaining antibodies [16] [20] |

| Fixation Solutions | Preserve cell monolayers for staining | Methanol, acetone-methanol mixtures [20] |

| Dilution Buffers | Prepare serial dilutions of virus samples | Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), maintenance medium [17] |

| Detection Antibodies | Identify infected cells (IFA readout) | Primary antibodies against viral proteins, fluorescent secondary antibodies [20] |

| qPCR Reagents | Quantify viral genomes (alternative readout) | DNA extraction kits, primers, probes, polymerases [20] |

The plaque assay and TCID50 method represent two fundamental, complementary approaches for quantifying infectious virus, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications. The plaque assay provides direct quantification of infectious units with higher precision and is considered the gold standard for viruses that form clear plaques, making it ideal for vaccine development, antiviral testing, and fundamental virology research. The TCID50 assay offers a statistical estimate of infectious titer through endpoint dilution, providing greater applicability to viruses that don't form plaques and advantages in throughput efficiency. The mathematical relationship between these units (1 TCID50 ≈ 0.7 PFU) enables cross-method comparisons and data integration [18]. Contemporary research increasingly combines these methods with molecular approaches like qPCR to differentiate between infectious and total viral particles, providing a more comprehensive understanding of viral dynamics [15] [20]. Method selection should be guided by viral characteristics, research objectives, and practical constraints, with many laboratories employing both approaches to leverage their complementary strengths in advancing virological research and therapeutic development.

In virology research and vaccine development, the accurate assessment of viral infectivity is foundational. Cell-based infectivity assays, such as plaque assays and the tissue culture infectious dose 50 (TCID₅₀) assay, serve as critical tools for quantifying infectious virus particles, evaluating antiviral therapies, and ensuring vaccine safety and potency [21] [22]. The selection of an appropriate cell line is arguably the most critical variable in these assays, as it directly influences assay sensitivity, specificity, and the kinetics of detectable viral replication. Permissive cell lines support robust viral entry and replication, leading to measurable endpoints like cytopathic effect (CPE), which can be visualized and quantified. The impact of this choice is evident across diverse virus families, from coronaviruses and adenoviruses to more complex viruses like human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) [23] [24] [25]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of cell line performance, supported by experimental data, to inform robust assay design.

Comparative Performance of Cell Lines

The sensitivity of a viral infectivity assay is intrinsically linked to the host cell's susceptibility to infection. Different cell lines express varying levels of viral receptors and host factors necessary for replication, leading to significant differences in assay outcomes. The following sections and tables summarize key experimental findings.

Case Study: SARS-CoV-2 and Adenovirus

Research on SARS-CoV-2 and human adenoviruses highlights how cell line selection can dramatically alter the detection of infectious virus.

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity of Cell Lines to Different Viruses

| Virus | Cell Lines Compared | Key Findings on Sensitivity | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Vero E6 vs. Vero E6-TMPRSS2 | Vero E6-TMPRSS2 extended analytical sensitivity by >3 CT values and resulted in faster viral isolation compared to parental Vero E6 cells. | Viral culture from clinical samples | [25] |

| Human Adenoviruses | 293A, A549, others | 293A and A549 were the most sensitive to enteric adenovirus serotypes 40 and 41. 293A detected viral plaques in 7 of 13 primary sewage samples. | Plaque assay in water samples | [23] |

| West Nile Virus (WNV) | Vero, Vero-E6, PER.C6 | Both Vero and Vero-E6 yielded higher viral titers than PER.C6 cells. | Endpoint titration for vaccine safety testing | [21] |

| Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) | ARPE-19 (epithelial) | The ARPE-19 epithelial cell line was selected for a potency assay due to the virus's specific reliance on a pentameric glycoprotein complex for epithelial cell entry. | High-throughput relative potency assay (IRVE) | [24] |

For SARS-CoV-2, the presence of the TMPRSS2 protease in modified Vero E6 cells is a critical differentiator, enhancing viral entry and thereby increasing the assay's ability to detect low levels of infectious virus that would be missed in standard Vero E6 cells [25]. Similarly, for adenoviruses, the 293A cell line demonstrated superior performance in environmental monitoring, successfully isolating viruses from complex primary sewage samples where other cell lines might fail [23].

Impact on Infectivity Quantification

The choice of cell line not only affects the binary detection of virus but also the quantitative results of an infectivity assay.

Table 2: Impact of Cell Line on Quantitative Assay Metrics

| Virus | Assay Type | Quantitative Impact | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Various (AdV, HSV, IAV, RV, VACV, SARS-CoV-2) | AI-based CPE detection (DVICE) | The AI model's accuracy (AUROC 0.991) was dependent on training with virus-specific CPE manifestations in specific cell lines (A549, HeLa, Huh7, VeroE6). | [11] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | RT-PCR-based infectivity prediction | A cycle threshold (Ct) cutoff of ≤31 for genomic RNA correlated with positive viral culture in Vero E6-TMPRSS2 cells, defining a rule-out threshold for infectivity. | [25] |

| HCMV | Imaging of Relative Viral Expression (IRVE) | Assay robustness was achieved by optimizing and fixing key cell-related parameters: cell density, serum concentration, and cell passage number. | [24] |

The data show that cell line permissiveness directly influences key quantitative metrics like viral titer and the effective dose (ED₅₀). Furthermore, the manifestation of CPE—a common endpoint in these assays—is highly specific to the virus-cell line pairing, which is a crucial consideration for both manual and automated readouts [11].

Advanced and Automated Methodologies

Traditional infectivity assays are often low-throughput and subjective. Recent advancements leverage automation, label-free imaging, and artificial intelligence (AI) to overcome these limitations, but these technologies still rely fundamentally on well-selected cell lines.

- Real-Time Cell Analysis (RTCA): Systems like the xCELLigence platform use cellular impedance to monitor CPE in real-time without labels. The optimal timepoint for infection and the resulting kinetics are dependent on the cell seeding density and the specific cell line used [22].

- AI-Powered Image Analysis: The DVICE (Detection of Virus-Induced CPE) framework uses convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to identify CPE from transmitted light microscopy images. This method requires training on specific cell lines (e.g., A549 for Adenovirus, Vero E6 for SARS-CoV-2) to learn the unique CPE "fingerprint" for each virus-cell combination [11]. Similarly, the AVIA (Automated Viral Infectivity Assay) platform uses AI on brightfield images to detect early, subtle phenotypic changes in infected cells, a process that is also cell line-dependent [26] [22].

- High-Throughput Fluorescence Imaging: Assays like the Imaging of Relative Viral Expression (IRVE) for HCMV automate the process of counting infected cells via immunostaining (e.g., for the Immediate Early 1 protein) in 384-well plates. This method's success hinges on using a susceptible cell line like ARPE-19 to ensure a strong and specific signal [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions as derived from the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Infectivity Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in Assay | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Vero E6 Cells | Standard cell line for isolation of SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses; susceptible to infection. | Used in SARS-CoV-2 culture as the gold standard for viability [27] [25]. |

| Vero E6-TMPRSS2 Cells | Engineered cell line expressing the TMPRSS2 protease; enhances entry of SARS-CoV-2 and increases assay sensitivity. | Critical for isolating SARS-CoV-2 from clinical samples with higher CT values [25]. |

| ARPE-19 Cells | Human retinal pigment epithelial cell line; permissive for HCMV infection due to expression of specific viral entry receptors. | Host cell in the automated IRVE potency assay for HCMV vaccine development [24]. |

| 293A Cells | Human embryonic kidney cell line; highly sensitive to certain adenoviruses, making it suitable for environmental monitoring. | Used for plaque assay detection of adenoviruses in water samples [23]. |

| Subgenomic RNA (sgRNA) Probes | PCR-based detection of viral sgRNA, a marker of active viral replication, used as a surrogate for infectivity. | sgE RNA detection showed high accuracy (98%) in identifying viable SARS-CoV-2 [27]. |

| Crystal Violet (CV) | A histochemical stain used to visualize and count viral plaques by fixing and staining the remaining cell monolayer. | Used as a ground truth staining method for training AI models in the DVICE framework [11]. |

| Anti-IE1 Antibodies | Antibodies targeting the HCMV Immediate Early 1 protein; used in immunostaining to identify infected cells in potency assays. | Key reagent in the IRVE assay for high-throughput counting of HCMV-infected cells [24]. |

Experimental Workflow and Logical Relationships

The diagram below illustrates the core decision-making workflow and the logical relationships between cell line selection, assay execution, and output interpretation in viral infectivity testing.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, here are detailed methodologies for two key assays cited in this guide.

The Imaging of Relative Viral Expression (IRVE) assay is an automated, high-throughput method for determining the relative potency of a live-attenuated HCMV vaccine.

- Cell Preparation: Seed ARPE-19 cells into 384-well plates using an automated cell culture system. Key parameters like cell density and cell passage number must be optimized and controlled for robustness.

- Infection: Inoculate the cell monolayer with serial dilutions of the HCMV vaccine sample. Include a reference standard on every plate for relative potency calculation.

- Incubation: Incubate the plates for a defined period (e.g., 24-48 hours) to allow for viral entry and early gene expression.

- Immunostaining: Fix the cells and perform immunofluorescence staining using an antibody against the HCMV Immediate Early 1 (IE1) protein. Use a nuclear counterstain to identify all cells.

- Automated Imaging and Analysis: Image the entire plate using a high-throughput microscope. Software is used to count the total number of nuclei and the number of IE1-positive nuclei. The percentage of infected cells is calculated for each dilution.

- Relative Potency Calculation: The half maximal effective dilution (ED₅₀) for both the test sample and the reference standard is determined. Relative potency is reported as the ratio of the reference ED₅₀ to the test sample ED₅₀.

This protocol uses label-free light microscopy and AI to quantify infectivity for a broad panel of viruses.

- Cell Seeding and Infection: Seed permissive cell lines (e.g., A549, Vero E6) in 96-well plates. Inoculate with serial dilutions of virus (e.g., Adenovirus, SARS-CoV-2). Include uninfected control wells.

- Image Acquisition: Incubate plates for up to 7 days. Acquire transmitted light (TL) images daily using a high-throughput microscope (e.g., ImageXpress Micro Confocal).

- Ground Truth Annotation: After imaging, fix the cells and stain with Crystal Violet (CV). Use human expert annotation of the CV-stained plates to define the infection state (positive/negative) for each well. This serves as the "ground truth" for training the AI model.

- AI Model Training: Train a convolutional neural network (CNN), such as EfficientNet-B0, using the TL images as input and the human annotations as labels. The model learns to recognize features associated with CPE.

- Infection Scoring and Titration: Use the trained model to classify the infection state of new TL images. Apply the specific infection (SIN) method to the classification results to calculate TCID₅₀ values, achieving a correlation with human annotation of R² = 0.986.

The selection of a cell line is a foundational decision that governs the sensitivity, accuracy, and applicability of viral infectivity assays. As demonstrated, a one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective; optimal cell lines must be matched to the specific virus based on its entry receptors and replication machinery. The emergence of advanced methodologies like real-time impedance sensing and AI-driven image analysis does not diminish the importance of cell line selection but rather reinforces it, as these technologies are trained on and optimized for specific virus-host systems. For researchers, a rigorous initial evaluation of cell line suitability, informed by comparative data, is essential for developing robust, reproducible, and predictive viral infectivity assays.

Core Conceptual Framework

Virucidal activity and neutralizing activity represent two distinct, critical mechanisms for preventing viral infections in biomedical research and therapeutic development. Virucidal activity refers to the chemical or physical destruction of viral particles in the environment, preventing infection by reducing the concentration of infectious virus on surfaces or in the air. In contrast, neutralizing activity describes the biological mechanism by which antibodies or other substances bind to viruses and block their ability to enter and infect host cells, representing a key immune protection mechanism [28].

The fundamental distinction lies in their mechanisms and applications: virucidal agents act directly on viral structural components through chemical or physical means, while neutralizing agents (particularly antibodies) function through specific molecular interactions that interfere with the viral replication cycle without necessarily destroying the viral particle. Understanding both concepts is essential for developing comprehensive strategies against viral pathogens, from surface disinfection protocols to vaccine efficacy assessment and therapeutic antibody development [28] [29].

Virucidal Activity: Mechanisms and Assessment

Chemical Virucidal Agents and Efficacy

Virucidal disinfectants demonstrate varying efficacy depending on their chemical composition, concentration, and contact time with pathogens. The susceptibility of viruses to these agents is heavily influenced by viral structure, with enveloped viruses generally being more susceptible than non-enveloped viruses due to the vulnerability of their lipid envelopes to disinfectants [29].

Table 1: Virucidal Efficacy of Chemical Disinfectants Against Enveloped Viruses

| Disinfectant Type | Specific Agent | Virus Tested | Effective Concentration | Minimum Contact Time | Log Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary Ammonium Compound | Micro-Chem Plus | Nipah Virus | 1:9 dilution | 15 seconds | >4 log₁₀ [30] |

| Quaternary Ammonium Compound | FWD | Nipah Virus | 1:27 dilution | 15 seconds | >4 log₁₀ [30] |

| Alcohol | Medical EtOH | Nipah Virus | 38% ethanol | 15 seconds | >4 log₁₀ [30] |

| Alcohol | Medical EtOH | Nipah Virus | 19% ethanol | 8 minutes | >4 log₁₀ [30] |

| Acidic Alcohol-Based | Proprietary Formulation | Human Norovirus (GII.17) | Product formulation | 30-60 seconds | Complete inactivation [31] |

| Alkaline Alcohol-Based | Proprietary Formulation | Human Norovirus (GII.17) | Product formulation | 60 seconds | No inactivation [31] |

The efficacy of virucidal agents is significantly influenced by their environment. Viruses suspended in solution are typically more easily inactivated than those dried on surfaces, where organic material like blood and saliva may provide protection. Furthermore, as demonstrated in the norovirus study, the pH formulation of alcohol-based disinfectants can dramatically impact their efficacy, with acidic formulations showing superior virucidal activity against nonenveloped viruses compared to alkaline formulations [29] [31].

Standardized Testing Methodologies

The European Committee for Standardization (CEN) has established a rigorous, phased framework for evaluating virucidal activity of chemical disinfectants:

Phase 1 (Suspension Tests): Preliminary tests to determine basic bactericidal, fungicidal, or virucidal activity without regard for specific application areas. These tests cannot be used for product claims [29].

Phase 2/Step 1 (Quantitative Suspension Tests): Quantitative methods where test organisms are exposed to disinfectants at various concentrations, contact times, and temperatures with interfering substances. The standard EN 14476 specifies a requirement of ≥4-log₁₀ reduction (99.99% loss of infectivity) for virucidal claims [29].

Phase 2/Step 2 (Carrier Tests): Methods simulating practical use conditions where microorganisms are applied to carrier surfaces (e.g., stainless steel, glass, PVC) and dried. These tests more accurately reflect real-world conditions, with standards including EN 16777:2018 for surface disinfection and EN 17111:2018 for instrument disinfection [29].

Figure 1: Standardized Virucidal Activity Testing Workflow. The European Committee for Standardization (CEN) three-phase testing methodology progresses from basic screening to simulated practical use conditions [29].

Neutralizing Activity: Mechanisms and Assessment

Antibody-Mediated Neutralization Mechanisms

Neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) represent a crucial component of the adaptive immune response, providing protection against viral infections through multiple mechanisms. The classical definition of neutralization describes it as "the loss of infectivity which ensues when antibody molecule(s) bind to a virus particle, and usually occurs without the involvement of any other agency" [28].

The mechanisms by which antibodies neutralize viruses are diverse and include:

Receptor Binding Interference: nAbs can bind to viral receptor-binding sites or their immediate vicinity, physically blocking attachment to host cell receptors through steric hindrance [28].

Post-Attachment Inhibition: Some nAbs permit initial attachment but prevent subsequent entry steps, such as viral fusion with host cell membranes or uncoating [28].

Conformational Alteration: High-affinity antibody binding can induce disassembly or conformational changes in viral surface proteins, rendering them non-functional for entry [28].

Virion Aggregation: Antibodies with multiple binding sites can cross-link viral particles, forming aggregates that reduce the effective infectious units [28].

It is important to distinguish between in vitro neutralization and in vivo protection. While in vitro assays typically measure direct blocking of viral entry, nAbs can mediate additional antiviral functions in vivo through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and phagocytosis [28].

Neutralization Assay Methodologies

Multiple assay formats have been developed to quantify neutralizing activity, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Comparison of Virus Neutralization Assay Methodologies

| Assay Type | Principle | Biosafety Level | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Virus Neutralization Test (cVNT) | Inhibition of authentic virus infection of permissive cells | BSL-3 for live SARS-CoV-2 [32] | Gold standard validation; pathogencity studies [33] | Measures authentic virus neutralization; considers all viral proteins | Requires high containment; longer turnaround time |

| Pseudovirus Neutralization Test (pVNT) | Neutralization of replication-incompetent viral particles pseudotyped with viral glycoproteins | BSL-2 [32] | High-throughput screening; vaccine efficacy studies [32] | Safer; enables study of high-pathogenicity viruses; scalable | Limited to single-cycle infection; may not fully recapitulate authentic virus neutralization |

| Surrogate Virus Neutralization Test (sVNT) | Competitive ELISA measuring antibody blockage of protein-protein interactions | BSL-1 [33] | Population serosurveillance; rapid clinical testing | Rapid; does not require live cells or viruses; high throughput | Measures only binding interference, not functional neutralization in cellular context |

| Inhibition Flow Cytometry VNT (IFVNT) | Flow cytometric detection of infected cells using fluorescent antibodies | BSL-2/3 depending on virus [33] | Detailed cellular infection analysis; monoclonal antibody characterization | Provides single-cell resolution; can quantify infection percentage directly | More complex instrumentation; potentially lower throughput |

Figure 2: Neutralization Assay Selection Framework. Assay choice depends on research objectives, balancing biosafety requirements with biological fidelity needs [33] [32].

The correlation between different neutralization assays has been extensively evaluated. Studies comparing pseudovirus-based neutralization assays (PVNA) with the gold standard micro-neutralization test (MNT) have demonstrated strong correlations, validating PVNA as a reliable tool for assessing anti-SARS-CoV-2 nAbs while offering the practical advantage of BSL-2 containment [32].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of virucidal and neutralizing activities requires specific research reagents and biological materials tailored to each methodology:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Inactivation Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Vero E6, Vero, RAW 264.7, CRFK, Huh7, Caco2, Calu3, HEK293T [30] [33] [31] | Virus propagation; neutralization assays; infectivity quantification | Provide cellular substrate for viral replication and infection detection |

| Reference Viruses | Murine norovirus (MNoV), Feline calicivirus (FCV), Vaccinia virus, Poliovirus, Adenovirus [29] [31] | Surrogate models; virucidal efficacy testing; assay standardization | Serve as representative models for pathogenic viruses requiring high containment |

| Detection Systems | Luciferase reporters, GFP, Horse-radish peroxidase (HRP) [33] [32] | Pseudovirus neutralization assays; surrogate neutralization tests | Enable quantification of infection levels through measurable signals |

| Viral Antigens | Recombinant spike protein, RBD proteins with His-tags [33] | Surrogate neutralization assays; antibody characterization | Provide target antigens for binding and neutralization studies |

| Standardized Disinfectants | Micro-Chem Plus, FWD, Medical EtOH [30] | Virucidal efficacy testing; reference standards | Serve as benchmark compounds for evaluating new virucidal agents |

| Reference Sera/Antibodies | NIBSC reference standards (20/136), WHO international standards [32] | Assay standardization; inter-laboratory comparison | Provide standardized controls for normalizing results across experiments |

Comparative Experimental Data Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Antiviral Efficacy

Direct comparison of virucidal and neutralizing activities reveals their complementary strengths in viral infection control:

Table 4: Side-by-Side Comparison of Representative Virucidal and Neutralizing Agents

| Parameter | Virucidal Agent (Micro-Chem Plus) | Virucidal Agent (Ethanol) | Neutralizing Antibody Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Pathogen | Nipah virus [30] | Human norovirus GII.17 [31] | SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1 & Variants [32] |

| Effective Concentration | 1:9 dilution (15 sec) [30] | Acidic formulation (30-60 sec) [31] | Serum dilution >1:10 to >1:160 [32] |

| Time to Efficacy | 15 seconds to 1 minute [30] | 30-60 seconds [31] | Days to weeks (immune response development) |

| Log Reduction/ Efficacy | >4 log₁₀ reduction [30] | Complete inactivation [31] | 90% infection inhibition (IC90) [32] |

| Primary Application | Surface decontamination; instrument disinfection [30] | Hand hygiene; surface disinfection [31] | Immune protection assessment; vaccine efficacy [32] |

| Duration of Effect | Immediate but transient | Immediate but transient | Weeks to months (immune memory) [34] |

Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Both virucidal and neutralizing activity assessments present methodological challenges that researchers must consider:

For virucidal testing, a significant limitation is the discrepancy between suspension tests and real-world conditions. The standardized suspension tests (EN 14476) expose viruses to large amounts of disinfectant in homogeneous solutions, making them easier to inactivate compared to viruses dried on surfaces where organic material may provide protection and surface interactions limit disinfectant access [29]. This challenge has been addressed through the development of carrier tests (EN 16777) that more accurately simulate practical conditions.

For neutralization assays, key considerations include the choice between authentic viruses versus pseudovirus systems. While authentic viruses provide the most biologically relevant data, they often require higher biosafety containment (BSL-3 for SARS-CoV-2) [32]. Pseudotyped viruses enable safer BSL-2 work and high-throughput screening but may not fully recapitulate all aspects of authentic virus entry and neutralization, particularly for viruses with complex entry mechanisms [28] [33].

Additionally, the dynamic nature of viral evolution presents challenges for both fields. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs) such as Delta and Omicron have demonstrated significant capacity to escape neutralizing antibody responses, reducing the efficacy of vaccine-elicited immunity [32]. Similarly, virucidal efficacy must be re-evaluated against emerging variants to ensure continued effectiveness of disinfection protocols.

Virucidal and neutralizing activities represent complementary approaches to viral infection control with distinct mechanisms, applications, and assessment methodologies. Virucidal activity testing provides critical data for environmental decontamination strategies using chemical agents that directly inactivate viral particles, with efficacy dependent on contact time, concentration, and formulation. Neutralizing activity assessment measures biological interference with viral infectivity, primarily through antibody-mediated mechanisms, serving as a key correlate of immune protection for vaccine development and therapeutic antibody evaluation.

The standardized frameworks established by organizations like the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) provide rigorous methodology for virucidal efficacy testing, while the evolving landscape of neutralization assays offers flexible options balancing biological fidelity with practical safety considerations. Researchers must select appropriate methods based on their specific applications, whether developing surface disinfectants, evaluating vaccine efficacy, or characterizing therapeutic antibodies, while acknowledging the limitations inherent in each approach. As viral threats continue to emerge, the complementary insights provided by both virucidal and neutralizing activity assessments will remain essential for comprehensive antiviral strategy development.

A Practical Guide to Viral Infectivity Assays: From Classic to Cutting-Edge

The plaque assay, developed in the early 1950s by Renato Dulbecco and Marguerite Vogt, remains the gold standard method for quantifying infectious viral titers and neutralizing antibodies in virology research [35] [36]. Despite the emergence of numerous alternative techniques, this foundational method continues to provide the most accurate measurement of replication-competent lytic virions, expressed as plaque-forming units per milliliter (PFU/ml) [37] [36]. Its enduring relevance stems from its unique ability to directly measure viral infectivity rather than simply detecting viral components, making it indispensable for vaccine development, antiviral testing, and serological studies [35] [38]. This guide examines the traditional plaque assay protocol, explores its modern automated counterparts, and provides a critical comparison of their respective capabilities, limitations, and applications in contemporary viral infectivity testing.

Experimental Protocol: Core Methodology

Traditional Plaque Assay Workflow

The fundamental plaque assay protocol involves infecting a confluent cell monolayer with serially diluted virus, restricting viral spread with a semi-solid overlay, and visualizing zones of cell death (plaques) after an incubation period [37] [36]. The standard methodology comprises these essential steps:

Cell Monolayer Preparation: The day before the assay, seed appropriate host cells (e.g., Vero E6, MDCK) into multi-well plates (commonly 6-, 12-, or 24-well format) and incubate until ~90-100% confluency is achieved [37] [39]. Different cell lines are required for different viruses.

Viral Inoculation: Prepare tenfold serial dilutions of viral samples in cell culture media [37] [36]. Rinse cell monolayers with buffer solution, then inoculate with diluted virus sample. Typical inoculation volumes are 500μl for a 12-well plate [39] or 100μl for a 6-well plate [38]. Incubate for 45-90 minutes with periodic rocking to ensure even coverage and prevent monolayer drying [37] [39].

Overlay Application: Following incubation, aspirate viral inoculum and apply a semi-solid overlay medium to restrict viral diffusion. Traditional options include:

- Agarose overlay: Mix 1:1 with 2x plaque media and heated 0.6% agarose for a final concentration of 0.3% [37] [39]

- Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC): Prepare 2% stock solution and treat similarly to agarose [37]

- Liquid overlays (Avicel): Mix 1:1 with 2x plaque media and 1.2-2.4% microcrystalline cellulose for final concentration of 0.6-1.2% [37]

Incubation and Plaque Development: Incubate plates for 2-14 days depending on viral growth kinetics [37] [36]. Plaque visibility timeframe varies significantly by virus: Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (VSV) may form plaques in 2 days, while slower-growing viruses like some echoviruses require up to 14 days [40].

Fixation and Staining: Fix cells with formaldehyde or similar fixative, then stain with crystal violet (1% in 20% ethanol), Giemsa, or methylene blue to visualize plaques as clear areas against a stained cell monolayer background [37] [36] [39].

Immunoplaque and Focus Forming Modifications

For viruses that do not cause complete cell lysis or require earlier detection, immunostaining modifications enable plaque visualization:

Immunoplaque Assay: Following fixation, permeabilize cells with Triton X-100, then incubate with virus-specific primary antibody (e.g., anti-NP antibody for influenza) [39]. Detect with enzyme-conjugated or fluorescent secondary antibodies and corresponding substrates [39]. This approach is particularly valuable for viruses with non-lytic replication cycles [36].

Fluorescent Focus Assay (FFA): As an alternative to chromogenic detection, use fluorescently-labeled antibodies (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 conjugates) for visualization by fluorescence microscopy [39]. This method often enables earlier plaque detection with enhanced sensitivity [36].

Data Interpretation and Quantification

PFU/ml Calculation and Statistical Considerations

The fundamental principle of plaque assay quantification assumes that each plaque originates from a single infectious viral particle [36] [40]. The viral titer is calculated using the formula:

PFU/ml = (Number of plaques) / (Dilution factor × Volume of inoculum in ml)

For reliable quantification, aim for plates containing 5-100 distinguishable plaques [37] [36]. Statistical variance approximates 10% for every 100 plaques counted when comparing sample replicates [37]. The dynamic range of accurate quantification depends on plate format and plaque size, with traditional 6-well plates typically accommodating up to 200 distinct plaques [36].

Plaque Morphology Analysis

Plaque characteristics provide valuable insights into viral behavior and pathogenicity [37]. Key morphological features to document include:

- Size variations: May indicate viral subpopulations with different replication kinetics or cytopathic effects [41]

- Clarity and border definition: Sharpness of plaque edges reflects the nature of cell-to-cell spread [37]

- Mixed morphologies: Can suggest genetic heterogeneity or competing viral quasispecies [41]

Technological Evolution: Automation Solutions

Advanced Imaging and Analysis Systems

Recent technological advancements address traditional plaque assay limitations through automation and enhanced imaging:

Lens-free holographic imaging: This label-free approach captures phase information from entire well plates (approximately 30 × 30 mm² area) at ~0.32 gigapixels per hour [38]. Combined with deep learning algorithms, it can detect VSV plaque-forming units in under 20 hours with >90% detection rate at 100% specificity, significantly reducing incubation times [38].

Integrated analysis systems: Commercial systems like the ImmunoSpot Analyzer (CTL) and ScanLab (MicroTechnix) standardize image acquisition and automate plaque counting, mitigating human bias and reducing analysis time from 6-10 minutes to 2-3 minutes per plate [35].

Real-time live-cell imaging: Instruments like IncuCyteS3 provide continuous observation of cellular events without fixation, enabling real-time analysis of neutralizing antibody quantification and viral replication kinetics [35].

High-Throughput Format Adaptations

Transitioning from traditional 6- or 12-well plates to 96-well formats significantly increases throughput. The µPlaque FFA system, for example, increases capacity from 4 samples/plate (24-well) to 16 samples/plate (96-well), enabling processing of 384 samples per run versus 32 with traditional formats [35].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Modern Approaches

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Plaque Assay Methodologies

| Parameter | Traditional Plaque Assay | Automated Imaging Systems | Lens-free Holography + Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (4 samples/24-well plate) | Medium (16 samples/96-well plate) | High (full well scanning) |

| Assay Duration | 3-10 days [35] | 3-5 days [35] | Significant reduction (e.g., VSV: <20h [38]) |

| Plaque Detection Method | Manual visualization after staining | Software-configured automated counting | Label-free, automated PFU detection |

| Data Integrity | Prone to human bias and variability | Audit trails, user access control [35] | Automated, reproducible quantification |

| Specialized Equipment Needs | Standard tissue culture equipment | Dedicated imaging systems (~$50,000+) | Compact device (<$880 parts cost) [38] |

| Personnel Requirements | Highly trained staff (2 persons) [35] | Reduced staff dependency (1 person) [35] | Minimal staff involvement after setup |

| Dynamic Range | Limited by plate size and countable plaques | Improved through software optimization | 10-fold larger than standard assays [38] |

| Key Limitations | Labor-intensive, subjective counting, long incubation | High initial equipment cost, training requirements | Emerging technology, validation ongoing |

Table 2: Alternative Viral Quantification Methods Comparison

| Method | What It Measures | Throughput | Time to Result | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque Assay | Infectious viral particles [36] | Low | 2-14 days [37] [36] | Labor intensive, requires lytic viruses |

| Focus Forming Assay (FFA) | Infectious units (antibody-detected) [36] | Medium | 1-3 days | Requires specific antibodies |

| TCID50 | Infectious dose (binary endpoint) [36] | Medium | 3-7 days | Less precise, statistical calculation |

| qPCR/qRT-PCR | Viral genome copies [37] [36] | High | Hours | Does not distinguish infectious vs. defective particles |

| Flow Cytometry | Viral proteins or infected cells [37] | High | 1-2 days | Complex sample processing, equipment cost |

| ELISA | Viral antigens [36] | High | 1 day | Does not measure infectivity |

| Electron Microscopy | Total viral particles [36] | Very Low | 1-2 days | Expensive, technically challenging |

Limitations and Considerations

Technical and Practical Constraints

Despite its gold standard status, the plaque assay faces several significant limitations:

Throughput Restrictions: Traditional formats process limited samples per run (e.g., 32 samples/run with 24-well plates versus 384 with improved alternatives) [35]

Temporal Constraints: Extended incubation periods (3-10 days depending on virus) delay experimental timelines [35] [36]

Expertise Dependency: Manual counting requires highly trained staff and remains prone to human bias, with operator-to-operator discrepancies affecting reproducibility [35]

Virus-specific Limitations: Some viruses do not form distinct plaques due to size or infection characteristics, requiring alternative approaches [35] [36]

Standardization Challenges: Methodology varies significantly between laboratories regarding cell lines, viral strains, incubation times, overlay types, and titer measurement methods (GMT, PRNT50, ID50), complicating cross-study comparisons [35]

Methodological Vulnerabilities

Common technical issues that compromise assay performance include:

Overlay Problems: Bubbles, lumps, or incomplete coverage from improper agarose handling or cold pipettes [41]

Inadequate Plaque Separation: Too many plaques leading to confluence and uncountable swaths of lysis [36] [41]

Non-viral Artifacts: Toxic components or undissolved agar particles creating false plaques [40]

Cell Monolayer Issues: Gaps in monolayers mistaken for plaques or insufficient confluence limiting infection spread [36]

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plaque Assays

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Virus-specific host cells for infection | Vero E6, MDCK (CCL-34, CRL-2935, CRL-2936) [39] [38] |

| Overlay Matrix | Restricts viral spread for discrete plaque formation | Agarose (0.3-0.6%), Carboxymethyl Cellulose (2%), Avicel (0.6-1.2%) [37] |

| Staining Solutions | Visualizes plaques against cell monolayer | Crystal violet (1%), Neutral red, Giemsa, MTT [37] |

| Fixation Agents | Preserves cellular architecture | Formaldehyde (10%), Methanol [37] [39] |

| Detection Antibodies | Immunoplaque assay components | Primary (e.g., H16-L10-4R5 for influenza NP), Secondary (enzyme-conjugated or fluorescent) [39] |

| Automated Imaging Systems | Standardizes image acquisition and analysis | ImmunoSpot Analyzer (CTL), ScanLab (MicroTechnix), IncuCyteS3 [35] |

| Multi-well Plates | Assay format and throughput determinant | 6-, 12-, 24-, 96-well formats [35] [36] |