CRISPR-Cas Phage Engineering: A Comprehensive Guide to Developing Next-Generation Antimicrobials and Biocontrol Agents

This article provides a detailed technical review for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging CRISPR-Cas systems for precise phage genome engineering.

CRISPR-Cas Phage Engineering: A Comprehensive Guide to Developing Next-Generation Antimicrobials and Biocontrol Agents

Abstract

This article provides a detailed technical review for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging CRISPR-Cas systems for precise phage genome engineering. We explore the foundational principles of phage biology and CRISPR mechanisms, detail cutting-edge methodologies for phage editing, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and compare the efficacy and safety of CRISPR-engineered phages with conventional antimicrobials. Our synthesis aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to advance phage-based therapies from the lab to the clinic, addressing the urgent need for novel strategies against antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

Bacteriophage Meets CRISPR: Understanding the Core Principles for Synergistic Engineering

The escalating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis necessitates novel therapeutic strategies. Bacteriophage (phage) therapy, the use of viruses to kill specific bacteria, is experiencing a renaissance. Modern synthetic biology, particularly CRISPR-Cas systems, enables the precise engineering of phages, transforming them into targeted, programmable antimicrobial agents. This application note details protocols and conceptual frameworks for developing CRISPR-Cas-enhanced phages within a broader thesis on engineered phage therapeutics.

Quantitative Data on AMR and Phage Therapy Potential

Table 1: Global Burden of Antimicrobial Resistance (Key Statistics)

| Metric | Value | Source/Year |

|---|---|---|

| Annual deaths attributable to AMR | ~1.27 million (direct), ~4.95 million (associated) | Lancet, 2022 |

| Bacteria with reported pan-drug resistance | Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, some Enterobacteriaceae | WHO, 2023 |

| Estimated annual cost of AMR to global economy | Up to $100 trillion USD by 2050 (projection) | World Bank, 2023 |

| Clinical trials involving phage therapy (registered) | > 40 active/recruiting trials | ClinicalTrials.gov, 2024 |

| FDA Phase 1/2 trial success rate for engineered phages | ~70% (preliminary safety/efficacy) | Recent Industry Reports, 2023 |

Table 2: Comparison of Phage Engineering Platforms

| Engineering Method | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Suitability for CRISPR Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous Recombination (in vivo) | No requirement for purified phage DNA | Low efficiency, laborious screening | Moderate |

| Bacteriophage Recombineering of Electroporated DNA (BRED) | Higher efficiency for dsDNA phages | Requires phage DNA preparation | High |

| Yeast Artificial Chromosome (YAC)-based assembly | Enables large genomic edits & rebooting | Complex, yeast-phage toxicity possible | Very High |

| CRISPR-Cas assisted editing | Direct selection against wild-type phage; high precision | Requires functional Cas in host | Primary Method |

| In vitro DNA assembly & rebooting (e.g., Gibson) | Complete synthetic control | Limited by genome size & transformation efficiency | High |

Core Protocols for CRISPR-Cas Engineered Phage Development

Protocol 2.1: Design and Assembly of CRISPR-Cas Phage Targeting Constructs

Objective: To create a donor DNA construct for inserting a CRISPR-Cas system into a phage genome. Materials:

- Target Phage Genomic DNA: Purified from propagated stock.

- Bacterial Host Genomic DNA: From the intended bacterial target strain.

- CRISPR Array Oligonucleotides: Designed to target essential or AMR genes in the pathogen.

- Cas Gene Cassette: e.g., cas9, cas3, or casΦ optimized for expression in target bacteria.

- Homology Arm Fragments: PCR-amplified from phage DNA (≥500 bp flanking insertion site).

- Assembly Master Mix: (e.g., NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix).

- Electrocompetent E. coli: For assembly product transformation.

Procedure:

- Select Insertion Locus: Identify a non-essential region in the phage genome (e.g., between structural genes) via bioinformatics.

- Amplify Homology Arms: PCR-amplify left and right homology arms from phage DNA.

- Design & Assemble CRISPR Array: Synthesize oligonucleotides encoding spacers targeting bacterial genes (e.g., blaNDM-1, mcr-1). Clone into a plasmid-based CRISPR array scaffold.

- Assemble Final Construct: Using an in vitro DNA assembly system, combine in one reaction: left homology arm, Cas gene expression cassette (with phage-specific promoter), CRISPR array, right homology arm.

- Transform & Verify: Transform assembled product into E. coli, isolate plasmid, and verify by restriction digest and Sanger sequencing across junctions.

Protocol 2.2: CRISPR-Cas Assisted Phage Engineering in a Recombinant Host

Objective: To replace the wild-type phage genomic region with the engineered construct containing the CRISPR-Cas system. Materials:

- Donor DNA Construct: From Protocol 2.1.

- Wild-type Phage Stock.

- Engineering Host Strain: Recombinant E. coli or target host expressing Cas protein and RecA/T recombination proteins.

- Electroporator.

- Soft Agar & Bottom Agar Plates.

- Phage Buffer: SM Buffer.

- PCR Reagents for screening.

Procedure:

- Prepare Recombinant Host: Transform the engineering host strain with a plasmid expressing RecA/T proteins if not endogenous.

- Introduce Donor DNA: Electroporate the linear donor DNA construct (gel-purified) into the recombinant host.

- Infect with Wild-type Phage: Immediately after electroporation, infect cells with a low MOI (~0.1) of wild-type phage. Allow adsorption.

- Plaque Assay: Mix with soft agar and plate on appropriate bottom agar. Incubate overnight.

- Screen for Recombinants: Pick individual plaques. Screen via PCR using one primer in the inserted Cas gene and one in the flanking phage genome. Confirm positive plaques by sequencing.

- Amplify & Purify: Propagate a positive recombinant plaque to high titer and purify via cesium chloride gradient or PEG precipitation.

Protocol 2.3:In VitroAssessment of Engineered Phage Efficacy

Objective: To compare the lytic and CRISPR-enhanced bactericidal activity of engineered vs. wild-type phage. Materials:

- Bacterial Target Strain: Antibiotic-resistant clinical isolate.

- Phage Stocks: Wild-type and CRISPR-Cas engineered phage (purified, titered).

- Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB).

- 96-well Microtiter Plate.

- Plate Reader (OD600).

- Colony Forming Unit (CFU) Plating Materials.

Procedure:

- Culture Bacteria: Grow target strain to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.4-0.6) in MHB.

- Set Up Kinetic Kill Curve: In a 96-well plate, mix bacteria (~10^5 CFU/well) with phage at varying MOIs (0.1, 1, 10) in triplicate. Include phage-only and bacteria-only controls.

- Monitor Growth: Place plate in plate reader, incubating at 37°C with continuous shaking. Measure OD600 every 15-30 minutes for 12-24 hours.

- Determine Viable Counts: At key timepoints (e.g., 2h, 6h, 24h), remove aliquots, perform serial dilutions in phage buffer, and plate for CFU counts.

- Analyze Data: Plot OD600 and log10(CFU/mL) over time. Compare the minimum phage concentration required for clearance and the rate of regrowth.

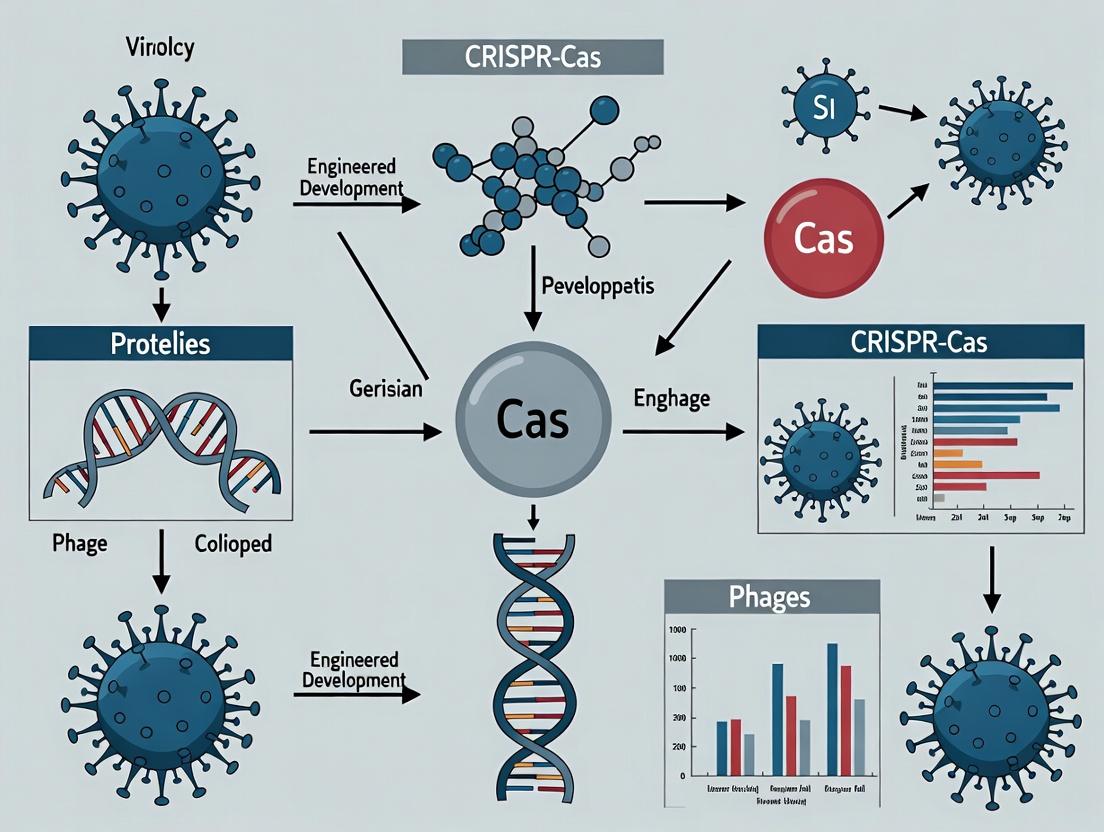

Diagrams & Visualizations

Title: Workflow for CRISPR-Cas Phage Engineering

Title: Dual-Action Mechanism of CRISPR-Engineered Phage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Phage Research

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Protocol | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Phage DNA Isolation Kit (e.g., Promega Wizard) | Purifies high-quality, high-molecular-weight phage genomic DNA for cloning/assembly. | Ensure minimal shearing; use wide-bore tips. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Assembly Master Mix (e.g., NEB HiFi, Gibson) | Seamlessly assembles multiple DNA fragments (homology arms, Cas, CRISPR array). | Critical for large, complex phage genome constructs. |

| Electrocompetent E. coli (High Efficiency) | Transformation host for plasmid and donor DNA assembly. | Strain choice (e.g., MC1061, PIR) affects DNA stability. |

| RecA/T Expression Plasmid | Provides recombination machinery in the engineering host for homologous recombination. | Inducible promoter (e.g., arabinose) allows control. |

| Cas Protein Expression System | Supplies Cas protein in trans during engineering to select against wild-type phage. | Match Cas type (Cas9, Cas3) to intended target nuclease activity. |

| Plaque Assay Materials (Agar, Soft Agar) | For phage titering, isolation, and purification of recombinant plaques. | Use appropriate media for the bacterial host. |

| qPCR/PCR Reagents for Phage Titering | Enables rapid, quantitative measurement of phage genomic copies. | Requires phage-specific primers; more rapid than plaque assay. |

| CsCl Gradient Solutions | Ultra-purification of phage particles for in vivo studies. | Removes endotoxins and cellular debris. |

1. Introduction: Within the Context of Engineered Phage Development The advent of CRISPR-Cas systems has revolutionized genetic engineering, providing unparalleled precision in genomic manipulation. Within the niche of engineered bacteriophage (phage) development, CRISPR-Cas tools serve a dual purpose: first, as a direct engineering tool to edit phage genomes for enhanced therapeutic properties, and second, as a selective countermeasure deployed by bacteria that phages must evade. This primer details the classes, mechanisms, and protocols central to leveraging CRISPR-Cas for advanced phage therapy research, a critical pillar in addressing antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

2. Classification and Mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas Systems CRISPR-Cas systems are broadly categorized into two classes based on the architecture of their effector complexes.

- Class 1 (Types I, III, IV) utilizes multi-subunit effector complexes (e.g., Cascade) for crRNA-guided target recognition. While complex, these systems, particularly Type I, are being harnessed in phage engineering for large DNA deletions.

- Class 2 (Types II, V, VI) employs single, multi-domain effector proteins (e.g., Cas9, Cas12, Cas13). Their simplicity has made them the cornerstone of most genetic engineering applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Predominant CRISPR-Cas Systems

| System (Type) | Class | Effector Protein | PAM Sequence (Example) | Cleavage Target | Primary Application in Phage Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type II (II-A) | 2 | Cas9 | 5'-NGG-3' (SpCas9) | dsDNA | Knock-in of therapeutic payloads, host range modification. |

| Type V-A (V-A) | 2 | Cas12a (Cpf1) | 5'-TTTV-3' | dsDNA | Multiplex gene editing, transcriptional repression in bacterial hosts. |

| Type VI (VI-D) | 2 | Cas13d | Non-specific (RNA-guided RNAse) | ssRNA | Targeting phage mRNA in bacterial hosts, diagnostics for phage replication. |

| Type I-E (I-E) | 1 | Cascade + Cas3 | 5'-AAA-3' (E. coli) | dsDNA (processive degradation) | Large-scale genomic deletions in phage genomes. |

Diagram Title: CRISPR-Cas System Classification & Phage Applications

3. Application Notes & Protocols for Phage Engineering Application Note 101: Employing Type II (Cas9) for Knock-in of Depolymerase Genes into a Phage Genome Objective: Integrate a polysaccharide depolymerase gene into a phage genome to enhance its ability to degrade bacterial biofilms. Rationale: Phage-encoded depolymerases can disrupt the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) of biofilms, exposing underlying bacteria to phage infection and lysis.

Protocol 101: Cas9-Mediated Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) in a Myoviridae Phage Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Workflow:

- Design & Cloning: Design two homology arms (~500 bp each) flanking the desired insertion locus in the phage genome. Clone these arms, flanking the depolymerase expression cassette, into a donor plasmid. Synthesize a crRNA sequence targeting the insertion locus PAM site.

- Complex Formation: Assemble the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex by incubating 10 pmol of purified Cas9 protein with 20 pmol of synthesized crRNA and 20 pmol of trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) for 10 min at 25°C.

- Electroporation: Mix 50 µL of high-titer phage lysate (>10^10 PFU/mL), 5 µL of RNP complex, and 200 ng of donor plasmid DNA. Electroporate into an E. coli host expressing recombinase proteins (e.g., RecET, Redαβγ) using a 1 mm cuvette (1.8 kV, 200 Ω, 25 µF). Immediately add 950 µL of recovery medium.

- Recovery & Plating: Recover cells for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking. Plate serial dilutions on a lawn of the target bacterial host using a double agar overlay method.

- Screening: Pick individual plaques. Screen via PCR using one primer inside the depolymerase gene and one primer outside the homology arm. Validate expression via SDS-PAGE of phage lysate proteins.

- Functional Assay: Assess biofilm degradation using a crystal violet assay on a 24-hour Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm treated with engineered vs. wild-type phage.

Diagram Title: Cas9 HDR Protocol for Phage Genome Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for CRISPR Phage Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Purified Cas9 Protein (SpCas9) | The Class 2 effector nuclease; creates a double-strand break at the target genomic locus to initiate HDR. |

| crRNA & tracrRNA (or sgRNA) | Guides the Cas9 protein to the specific DNA target sequence via Watson-Crick base pairing. |

| Electrocompetent E. coli (expressing RecET/Red) | Bacterial host for phage propagation and electroporation; recombinase systems enhance HDR efficiency from the donor plasmid. |

| Donor Plasmid (HDR Template) | Contains the therapeutic gene (e.g., depolymerase) flanked by homology arms; serves as the template for precise insertion. |

| Phage Lysate (High Titer) | The target genome to be engineered; high PFU/mL ensures sufficient template for successful recombination events. |

| Electroporator & 1mm Cuvettes | Device for delivering a high-voltage pulse to temporarily permeabilize bacterial cells, allowing entry of RNP and DNA. |

4. Quantitative Data on Engineering Efficiency Table 2: Representative Efficiency Metrics from Recent Phage Engineering Studies

| Engineering Goal | CRISPR-Cas System Used | Reported Efficiency (Success Rate) | Key Factor Influencing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Knock-in (5-10 kb) | Type II (Cas9 + HDR) | 0.5% - 3.0% of total plaques | Length & symmetry of homology arms; host recombinase activity. |

| Gene Deletion (<5 kb) | Type I-E (Cascade + Cas3) | ~10^2 - 10^3 fold enrichment over wild-type | Processivity of Cas3 helicase-nuclease. |

| Point Mutation (SNP) | Type V (Cas12a + HDR) | 1.0% - 4.5% of total plaques | crRNA specificity; avoidance of off-target effects. |

| Bacterial Host CRISPR Knockout | Type II (Cas9) | >90% mutant isolation efficiency | Essential for creating permissive hosts for phage propagation. |

5. Future Perspectives in Engineered Phage Research The integration of next-generation CRISPR tools, such as base editors (Cas9-derived) and prime editors, will enable more subtle, efficient engineering of phage genomes without requiring double-strand breaks or donor templates. Furthermore, the use of endogenous bacterial Type I CRISPR-Cas systems to selectively pressure phages in situ is a promising direction for evolving phages with enhanced therapeutic properties. The synergy between CRISPR biology and phage engineering continues to be a foundational thesis for developing precision antimicrobials.

Within the broader thesis on CRISPR-Cas system integration into engineered phage development, this application note details the synergistic potential of bacteriophages as precision delivery vehicles for CRISPR antimicrobials. Phages offer natural tropism, high bacterial infection efficacy, and programmable payload capacity.

Quantitative Advantages of Phage Vectors

Table 1: Comparative Metrics of Delivery Vectors for Bacterial Targeting

| Vector Characteristic | Engineered Phage | Conjugative Plasmid | Lipid Nanoparticle | Naked DNA/RNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery Efficiency to Bacteria | >10^8 PFU/µg DNA | Moderate (10^-3 - 10^-5) | Low (<10^-6) | Negligible |

| Host Specificity | High (Species/Strain level) | Broad (Conjugation+) | Very Low | None |

| Payload Capacity (kb) | 10-150+ (λ phage: 48.5) | 10-300 | ~10 | N/A |

| Immune System Evasion (in vivo) | Moderate (encapsulated) | Low | High (PEGylated) | Low |

| Manufacturing Scalability | High (bacterial culture) | High (fermentation) | Moderate/Complex | High |

| Typical CRISPR Editing Rate | 10^-2 - 10^-1 | 10^-4 - 10^-2 | <10^-6 | N/A |

| Primary Application | Targeted antimicrobials, microbiome editing | Lab bacterial engineering | Eukaryotic cells | In vitro use |

Table 2: Published Efficacy of Phage-Delivered CRISPR-Cas Systems (2022-2024)

| Target Bacterium | Phage Vector | CRISPR System | Payload | Reduction in Bacterial Load in vivo | Key Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (UPEC) | T7 phage | Cas9 | fimH gene targeting | >4-log in murine model | Richter et al., 2023 |

| S. aureus (MRSA) | ΦNM1 phage | Cas9 | mecA & fnbA targeting | >99.9% in biofilm model | Younis et al., 2024 |

| K. pneumoniae (CRKP) | λ phage derivative | Cas3 (CRISPR-Cas3) | Chromosomal degradation | 3.5-log reduction | Chen & Chen, 2024 |

| E. faecalis (VRE) | ΦFL1A | Cas12a (Cpf1) | vanA cluster | 99.7% elimination in gut colonization model | Park et al., 2022 |

| P. aeruginosa | M13 modified | dCas9 (CRISPRi) | lasR gene silencing | 85% virulence attenuation | Silva et al., 2023 |

Core Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering a CRISPR-Cas9 Payload into a Lysogenic Phage Genome

Objective: Insert a CRISPR expression cassette (spacer + cas9 + promoter) into a temperate phage genome for chromosomal integration and subsequent induction.

Materials:

- Bacterial strain: Lysogen carrying the target prophage (e.g., E. coli λ lysogen).

- Plasmid: pCRISPR-Kan (or similar) containing: PL promoter, cas9, sgRNA scaffold, homology arms to phage attachment site (attP), KanR.

- Electrocompetent cells: Prepared from the lysogen.

- Induction agents: Mitomycin C (0.5 µg/mL) or UV crosslinker.

- PEG/NaCl solution for phage precipitation.

- SM Buffer for phage resuspension.

Procedure:

- Electroporation: Introduce 100 ng of pCRISPR-Kan into 50 µL electrocompetent lysogen cells. Recover in SOC medium for 2 hours at 37°C.

- Selection: Plate on LB + Kanamycin (50 µg/mL). Incubate overnight.

- Screen Colonies: PCR-verify correct plasmid integration using primers flanking the attP site.

- Prophage Induction: Grow a verified colony to OD600 0.3. Add Mitomycin C (0.5 µg/mL) or expose culture to UV light (25 J/m²). Shake for 3-4 hours until lysis occurs.

- Phage Harvest: Centrifuge lysate at 8,000 x g for 10 min to remove debris. Filter supernatant (0.45 µm). Precipitate phage particles with 1/10 vol PEG/NaCl (20% PEG-8000, 2.5 M NaCl) overnight at 4°C.

- Pellet & Resuspend: Centrifuge at 12,000 x g, 30 min, 4°C. Discard supernatant. Resuspend pellet in 1 mL SM Buffer.

- Titer & Validate: Perform plaque assay. Isolate phage DNA, sequence CRISPR cassette.

Protocol 2:In VitroAssessment of CRISPR-Phage Antimicrobial Activity

Objective: Quantify the killing efficacy and specificity of the engineered CRISPR-phage against target and non-target bacteria.

Materials:

- Engineered CRISPR-phage stock (≥10^9 PFU/mL from Protocol 1).

- Target bacterial strain (wild-type, contains protospacer).

- Non-target control strain (isogenic, spacer mismatch or lacks PAM).

- 96-well microtiter plates with optical bottoms.

- Automated plate reader (capable of OD600 and fluorescence).

Procedure:

- Culture Bacteria: Grow target and non-target strains to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.5).

- Infect: In a 96-well plate, mix 100 µL bacterial culture (~10^5 CFU) with 100 µL of CRISPR-phage at varying MOI (0.1, 1, 10) in triplicate. Include phage-only and bacteria-only controls.

- Monitor Growth: Place plate in reader. Cycle: 37°C with continuous shaking. Measure OD600 every 15 minutes for 24 hours.

- Assess Cell Death: Include a membrane-impermeant DNA stain (e.g., propidium iodide) in a parallel set of wells. Monitor fluorescence (Ex/Em ~535/617 nm) as a correlate of CRISPR-induced cell lysis.

- Plate for Viability: At 4h and 24h, remove 10 µL from each well, serially dilute, and spot on agar plates for CFU enumeration.

- Analyze: Calculate bacterial reduction as log10(CFUcontrol/CFUtreated). Plot growth curves and killing kinetics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Phage Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Product/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Phage DNA Isolation Kits | Purify high-quality, high-molecular-weight phage genomic DNA for cloning or sequencing. | Norgen Phage DNA Isolation Kit; Thermo Fisher GeneJET Lambda Kit. |

| In vitro CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Validate sgRNA cutting efficiency on purified target bacterial DNA before phage engineering. | IDT Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3; NEB HiFi Cas9. |

| Gibson Assembly or HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix | Seamlessly assemble large phage genome fragments with CRISPR cassette inserts. | NEB Gibson Assembly Master Mix; Takara In-Fusion Snap Assembly. |

| Electrocompetent Cell Preparation Buffer (10% Glycerol) | Prepare highly transformable bacterial cells for phage genome electroporation. | Lab-prepared 10% glycerol in ultra-pure water, 0.22 µm filtered. |

| PEG-8000/NaCl Precipitation Solution | Concentrate and partially purify phage particles from lysates. | 20% PEG-8000, 2.5 M NaCl in autoclaved water. |

| Phage Titering Agar (Double-Layer Agar) | For accurate plaque assay enumeration of phage particles (PFU/mL). | LB with 0.5% agar (top) and 1.5% agar (bottom). |

| Bacterial Genomic DNA Spacer Screening Kit | Confirm presence of protospacer and PAM site in target bacteria. | QuickExtract DNA Solution (Lucigen) + PCR primers. |

| Fluorescent Cell Viability Stains (SYTOX, PI) | Distinguish between phage lytic death and CRISPR-induced bactericidal activity. | Thermo Fisher SYTOX Green/Red; Propidium Iodide (Sigma). |

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

Diagram Title: CRISPR-Phage Engineering & Testing Workflow

Diagram Title: Mechanism of Phage-Delivered CRISPR Killing

The integration of CRISPR-Cas systems into bacteriophage engineering represents a paradigm shift, enabling precise genomic manipulation and the creation of "smart" antimicrobials. The choice of phage chassis—specifically the well-characterized systems of T4, T7, and Lambda—is critical. Each presents unique advantages and trade-offs, particularly between lytic and temperate life cycles, which must be evaluated against the intended application, such as evading host defenses or delivering CRISPR payloads.

Key Phage Systems: Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Model Phage Systems

| Feature | T4 | T7 | Lambda (λ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle | Strictly Lytic | Strictly Lytic | Temperate (Lytic/Lysogenic) |

| Genome Type | dsDNA, 169 kbp, hydroxymethylcytosine | dsDNA, 40 kbp, linear | dsDNA, 48.5 kbp, cos ends |

| Primary Host | E. coli B & K-12 strains | E. coli K-12, B strains | E. coli K-12 |

| Infection Time ~25-30 min | ~17 min | ~35-45 min (lytic) | |

| Engineering Suitability | High capacity for large inserts; complex morphogenesis. | Simple genetics, strong polymerase promoter, easy engineering. | Well-understood genetic switch; lysogeny enables stable gene delivery. |

| Key Advantage for CRISPR Delivery | High payload capacity for multi-Cas systems & large guide arrays. | Rapid, direct expression from phage polymerase promoter. | Lysogenic integration allows permanent chromosomal insertion of CRISPR cassettes. |

| Major Engineering Challenge | Complex genome with modified bases requiring specific protocols. | Limited packaging capacity (~105% of wild-type). | Excision/induction control required to trigger lytic/CRISPR cycle. |

Table 2: Lytic vs. Temperate Trade-offs for CRISPR-Phage Development

| Parameter | Lytic Phage Chassis (e.g., T4, T7) | Temperate Phage Chassis (e.g., Lambda) |

|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Safety | Superior; no natural lysogeny, self-limiting. | Risk of lysogeny & horizontal gene transfer; requires safeties. |

| Bacterial Killing Speed | Very fast; direct lysis. | Can be delayed pending induction from lysogeny. |

| CRISPR Payload Delivery Efficiency | High copy number delivery during infection. | Single-copy, stable chromosomal integration possible. |

| Payload Persistence | Transient. | Long-term, heritable if lysogenized. |

| Programmability (Timing) | Immediate expression upon infection. | Controllable (e.g., via chemical induction of lytic cycle). |

| Key Application | Direct killing + CRISPR-Cas mediated ablation (e.g., targeting AMR genes). | Bacterial re-sensitization (e.g., disrupting antibiotic resistance plasmids stably). |

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering a CRISPR-Cas9 System into Phage T7 Objective: To replace a non-essential gene region in T7 with a Cas9 and sgRNA expression cassette for targeted bacterial killing.

Materials & Reagent Solutions:

- Phage T7 Wild-Type Genomic DNA: Template for recombination.

- pCRISPR-T7 Plasmid (Recombineering Plasmid): Contains Cas9-sgRNA cassette flanked by T7 homology arms (≈500 bp each).

- Electrocompetent E. coli BL21 (DE3): High-efficiency transformation host for recombineering.

- Plasmid pSG1 (Inducible Phage T7 Gene 1.5-1.7): Provides T7 proteins for in vivo genome replication upon induction.

- Luria-Bertani (LB) Broth/Agar: Standard microbial growth media.

- Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG): Inducer for pSG1 plasmid, initiating phage genome replication.

- PEG 8000/NaCl Solution: For phage precipitation and concentration.

- Phage DNA Isolation Kit: For purifying engineered genomes for verification.

- Taq PCR Master Mix & Gel Electrophoresis System: For screening recombinant phages.

Methodology:

- Clone: Insert the desired sgRNA sequence (targeting, e.g., a bacterial blaNDM-1 gene) into the pCRISPR-T7 plasmid.

- Co-transform: Introduce both pCRISPR-T7 and pSG1 plasmids into electrocompetent E. coli BL21.

- Induce Recombination: Grow cells to mid-log phase, add IPTG to induce T7 proteins from pSG1, then transfer with T7 wild-type genomic DNA.

- Phage Recovery: After lysis, harvest lysate. Perform serial plaque assays on E. coli BL21.

- Screen Plaques: Pick individual plaques. Use PCR with primers outside the homology arms to check for cassette insertion.

- Amplify & Validate: Propagate PCR-positive phage. Isolate phage DNA to confirm integrity via sequencing across the insertion site.

- Functional Assay: Spot purified engineered phage on lawns of target (NDM-1 positive) and non-target bacteria. Observe specific inhibition.

Protocol 2: Inducible Lytic Cycle Trigger for Lambda-based CRISPR Delivery Objective: To modify a temperate Lambda phage to carry a CRISPR-Cas system and ensure its controlled, lytic-phase delivery via external induction.

Materials & Reagent Solutions:

- Lambda EMBL4 or gt11 Vector: Accepts large inserts; contains removable "stuffer" region.

- CRISPR-Cas AAV Vector Donor Fragment: Contains a Cas9(D10A) nickase and sgRNA expression unit.

- In vitro Packaging Extracts (Lambda): Commercial mix of phage capsids/tails for packaging recombinant genomes.

- E. coli strains C600 (permissive) & R594 (non-permissive for red gam-): For plating and selective amplification.

- Temperature-Sensitive Lambda cI857 Repressor Lysogen: Host for propagation; lytic cycle induced at 42°C.

- Mitomycin C: Chemical inducer of the SOS response/S RecE pathway.

- NZY Broth/Agar: Optimized for Lambda phage work.

- Restriction Enzymes (EcoRI, BamHI) & T4 DNA Ligase: For vector preparation and insert cloning.

- DpnI Enzyme: To digest methylated parental plasmid DNA after in vitro mutagenesis.

Methodology:

- Vector Preparation: Digest Lambda EMBL4 vector with EcoRI and BamHI to remove stuffer fragment. Gel-purify the arms.

- CRISPR Insert Ligation: Ligate the CRISPR-Cas donor fragment into the prepared vector arms.

- In vitro Packaging: Mix the ligated DNA with commercial packaging extracts to produce infectious phage particles.

- Plaque Formation: Plate packaged phage on E. coli C600 lawn. Pick plaques into SM buffer.

- Lysogen Creation & Induction: Infect a E. coli strain with the recombinant Lambda at low MOI at 32°C to establish lysogens. For induction, shift growing culture to 42°C or add Mitomycin C (1-2 µg/mL).

- Phage & CRISPR Delivery Harvest: After lysis (3-5 hrs post-induction), filter lysate. This lysate contains phage particles capable of delivering the CRISPR payload upon subsequent infection.

- Efficiency of Plating (EOP) Assay: Titrate lysate on a bacterial strain carrying a functional antibiotic resistance gene (target) vs. a non-functional mutant. Reduced EOP on the target strain indicates successful CRISPR-mediated killing.

Diagrams & Visualizations

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Phage Engineering Workflow

Diagram 2: Lambda Lytic/Lysogenic Decision & Induction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Phage Engineering

| Reagent | Function in Research | Example/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Phage Genomic DNA Isolation Kit | Purifies high-quality, packagable phage DNA for engineering. | Norgen Phage DNA Isolation Kit |

| Electrocompetent E. coli (High Efficiency) | Essential for phage recombineering and plasmid transformation. | NEB 10-beta Electrocompetent E. coli |

| In vitro Lambda Packaging Extracts | Packages recombinant Lambda DNA into infectious virions. | MaxPlax Lambda Packaging Extracts |

| CRISPR Clone Synthesis Service | Custom synthesis of gRNA scaffolds & Cas expression cassettes. | Twist Bioscience gBlocks Gene Fragments |

| Temperature-Controlled Shaker/Incubator | Critical for Lambda lysogen growth and precise thermal induction. | New Brunswick Innova S44i |

| Plaque Picker & Liquid Handling Robot | For high-throughput isolation and screening of recombinant plaques. | Copacabana Plate Sealer & Picker |

| qPCR System with SYBR Green | Quantifies phage genomic copies and checks CRISPR expression levels. | Bio-Rad CFX96 Touch |

| Next-Gen Sequencing Kit (Amplicon) | Validates engineered phage genome integrity and checks for off-targets. | Illumina MiSeq 16S/ITS kit |

Application Notes: Evolution of Phage Engineering Technologies

The development of engineered bacteriophages for therapeutic and diagnostic applications has progressed through distinct technological eras, culminating in the precision of CRISPR-Cas systems. These notes contextualize this evolution within modern phage development research.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key Phage Engineering Technologies

| Technology Era | Key Technique(s) | Typical Efficiency (Desired DNA Integration) | Key Limitation | Primary Application in Phage Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Genetics (1970s-1990s) | In vivo homologous recombination, Chemical mutagenesis | 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻⁴ | Labor-intensive screening, non-targeted mutations | Early phage biology studies, basic vector development |

| Bacteriophage Recombineering (2000s) | Electroporation of oligonucleotides (BRED, DaRT) | 10⁻⁵ – 10⁻² | Requires specific host strains, size limits on inserts | Targeted gene knockouts, small insertions/deletions |

| Yeast-Based Assembly (2010s) | Yeast Artificial Chromosome (YAC) & homologous recombination | Up to ~90% for whole phage genomes | Requires yeast handling, genome extraction | Rebooting of large, complex phage genomes, large-scale refactoring |

| CRISPR-Cas Counterselection (Current) | Cas9/gRNA cleavage of wild-type phage DNA | Can exceed 99% enrichment of edited phages | Requires prior knowledge of PAM sites, phage delivery | High-efficiency, multiplexed editing, functional genomics |

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Knock-in for Therapeutic Phage Development

Objective: To insert a heterologous antimicrobial gene (e.g., lysB) into a temperate phage genome with high efficiency using CRISPR-Cas9 counterselection.

I. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Bacterial Host Strain | E. coli expressing a plasmid-derived Cas9 and a phage-specific gRNA. |

| Donor DNA Template | dsDNA fragment containing target gene flanked by ≥500 bp homology arms to phage target locus. |

| Electrocompetent Cells | Prepared from the above bacterial host for high-efficiency DNA transformation. |

| Phage Dilution Buffer (SM Buffer) | 100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO₄·7H₂O, 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 0.01% gelatin; for phage stock storage and dilution. |

| Cas9/gRNA Expression Plasmid | e.g., pCas9; provides inducible expression of Cas9 and a user-defined guide RNA targeting the phage insertion site. |

| Recovery Media | SOC Outgrowth Medium: 2% Tryptone, 0.5% Yeast Extract, 10 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MgSO₄, 20 mM glucose. |

| Selection Agar | LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics for plasmid maintenance and for selecting recombinant phages (if applicable). |

II. Detailed Protocol

A. Preparation of Electrocompetent gRNA/Cas9 Host Cells

- Transform the Cas9/gRNA plasmid into an appropriate E. coli strain (e.g., MG1655) via standard heat-shock.

- Inoculate a single colony in 5 mL LB + antibiotic. Grow overnight at 30°C with shaking (250 rpm).

- Subculture 1:100 into 50 mL fresh, pre-warmed LB + antibiotic in a 250 mL flask. Grow at 30°C to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.5-0.6.

- Chill culture on ice for 30 min. Pellet cells at 4,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C.

- Wash pellet gently with 50 mL of ice-cold, sterile 10% glycerol. Repeat wash twice.

- Resuspend final pellet in 1 mL ice-cold 10% glycerol. Aliquot 50 µL into pre-chilled tubes. Use immediately or store at -80°C.

B. Phage Infection and Donor DNA Co-Electroporation

- Induce Cas9/gRNA: Grow a 5 mL culture of the electrocompetent cells from Step A.6 at 30°C to OD₆₀₀ ~0.4. Add inducer (e.g., 0.2% L-arabinose for pCas9) and incubate for 30 min.

- Infect Cells: Add wild-type phage at an MOI of 0.1-0.5 to 1 mL of induced cells. Incubate statically at 37°C for 10 minutes.

- Prepare Electroporation Mix: Combine 50 µL of infected cells with 100-200 ng of purified donor DNA fragment. Mix gently.

- Electroporate: Transfer mix to a 1 mm electroporation cuvette. Pulse at 1.8 kV, 25 µF, 200 Ω.

- Recover: Immediately add 950 µL of pre-warmed SOC medium. Transfer to a culture tube and incubate at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) for 2 hours to allow for phage replication and CRISPR selection.

C. Plaque Assay and Screening for Recombinants

- Serially dilute the 2-hour recovery culture in SM Buffer.

- Mix 100 µL of appropriate dilutions with 200 µL of a fresh, non-Cas9 expressing indicator bacterial culture (to avoid continued CRISPR selection during plating).

- Add 3 mL of soft agar (0.7% agar in LB), mix, and pour onto pre-warmed LB agar plates. Let solidify.

- Incubate plates overnight at 37°C.

- The Cas9 cleavage of non-recombinant (wild-type) phage DNA in the initial host enriches for recombinants. Pick 10-20 individual plaques.

- Amplify each plaque in a small culture of indicator bacteria. Isolate phage DNA via a miniprep kit (e.g., Promega Wizard DNA Clean-Up).

- Screen phage DNA by PCR using primers flanking the insertion site and sequencing to confirm precise knock-in of the lysB gene.

Diagram Title: CRISPR-Cas9 Engineering of Therapeutic Phage

Protocol: High-Throughput Phage Functional Genomics via CRISPRi

Objective: To perform CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) screening for essential gene identification in a lytic phage using a pooled, catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) library.

I. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Pooled CRISPRi Phage Library | A lytic phage genome cloned as a fosmid in E. coli, with an array of ~100 bp guide RNA sequences targeting every phage ORF, expressed from a constitutive promoter. |

| dCas9 Expression Strain | E. coli strain constitutively expressing dCas9 (e.g., from a chromosomal locus). |

| Induction Media | LB supplemented with inducer (e.g., IPTG or anhydrotetracycline) to trigger phage genome excision and replication from the fosmid. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Reagents | Kit for amplicon sequencing of the gRNA cassette (e.g., Illumina MiSeq). |

| Lysis Buffer (for phage DNA) | 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 100 µg/mL Proteinase K. |

| Magnetic Beads for DNA Cleanup | SPRIselect beads for PCR product purification and size selection. |

II. Detailed Protocol

A. Library Transformation and Challenge

- Transform the pooled phage CRISPRi fosmid library into electrocompetent dCas9 expression cells. Plate on selective agar to obtain >1000x library coverage. Pool all colonies by scraping plates.

- Inoculate the pooled library into 50 mL of LB + antibiotic + inducer (to initiate phage development from the fosmid). Grow at 37°C with shaking for 4-6 hours until lysis is observed.

- Centrifuge the lysate at 8,000 x g for 10 min to remove debris. Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm filter to obtain a clear phage stock ("Output Library").

B. gRNA Abundance Analysis by NGS

- Extract Nucleic Acid: Treat 1 mL of both the initial cell pool ("Input Library") and the "Output Library" phage stock with DNase I (5 U, 37°C, 30 min) to remove unpackaged DNA. Inactivate DNase I with 5 mM EDTA.

- Extract Phage DNA: Add lysis buffer and Proteinase K to the DNase-treated samples. Incubate at 56°C for 1 hour. Purify DNA using a standard phenol-chloroform extraction or commercial kit.

- Amplify gRNA Cassette: Perform PCR on the purified DNA using primers adding Illumina adapters and unique sample indexes. Use 8-10 cycles to minimize bias.

- Purify and Sequence: Clean up PCR products with SPRIselect beads. Quantify by qPCR, pool equimolar amounts, and sequence on an Illumina MiSeq platform (single-end, 150 bp).

C. Data Analysis and Essential Gene Identification

- Read Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the reference list of gRNA sequences using a lightweight aligner (e.g., Bowtie 2).

- Count gRNA Reads: Generate a count table for each gRNA in the Input and Output samples.

- Calculate Fold-Change: For each gRNA i, compute the log₂ fold-change (log₂FC) using a formula like: log₂((OutputCounti + 1) / (InputCounti + 1)).

- Identify Essential Genes: gRNAs targeting essential phage genes will be significantly depleted in the output library (negative log₂FC). Perform statistical analysis (e.g., using DESeq2 or edgeR) to rank genes by essentiality. Genes with a false-discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and log₂FC < -2 are strong essential gene candidates.

Diagram Title: CRISPRi Functional Genomics Screen for Phage Genes

Step-by-Step Protocols: Designing and Executing CRISPR-Cas Phage Genome Editing

This application note is situated within a broader thesis on CRISPR-Cas systems for engineered phage development, a promising frontier in precision antimicrobial therapy and synthetic biology. The selection of an appropriate Cas nuclease is critical for successful genome editing of bacteriophages, which involves unique challenges such as high GC content, compact genomes, and the need for efficient delivery and activity within bacterial hosts. This document provides a comparative analysis and detailed protocols for utilizing three prominent Cas nucleases—Cas9, Cas12a, and Cas3—in phage genome engineering workflows.

Comparative Analysis of Cas Nucleases for Phage Engineering

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Cas Nucleases for Phage Genome Editing

| Feature | Cas9 (SpCas9) | Cas12a (Cpfl) | Cas3 (CRISPR-Cas3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class/Type | Class 2, Type II | Class 2, Type V | Class 1, Type I |

| Guide RNA | Dual (crRNA+tracrRNA) or sgRNA | Single crRNA | crRNA + Cascade complex |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' (SpCas9) | 5'-TTTV-3' (AsCas12a) | 5'-AAG-3' (Type I-E) |

| Cleavage Mechanism | Blunt ends, DSB | Staggered ends, DSB | Processive, long-range degradation |

| Cleavage Site | Within seed region | Distal to PAM | Begins at target, proceeds processively |

| Primary Application in Phage | Precise gene knock-outs/ins | Multiplexed knock-outs | Large deletions, genome reduction |

| Noted Efficiency in Phage | High (60-95%) | Moderate to High (50-80%) | High for large deletions (>90% reduction) |

| Key Advantage | High precision, well-established | Simpler gRNA, multiplexing | Drastic genome restructuring |

Table 2: Selection Guide Based on Phage Engineering Goal

| Desired Genomic Outcome | Recommended Nuclease | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Single gene knock-out or insertion | Cas9 | Reliable, high-efficiency DSB for homologous recombination. |

| Multiplexed knock-out of several genes | Cas12a | Efficient processing of a single crRNA array targeting multiple sites. |

| Large-scale genomic deletion (>10 kb) | Cas3 | Processive excision ideal for removing non-essential genomic regions. |

| High-GC content phage genome | Cas12a | Less constrained by GC content than Cas9; T-rich PAM often available. |

| Phage genome "miniaturization" | Cas3 | Unmatched for progressive degradation to create streamlined phage. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout in a Lytic Phage Genome

Objective: To disrupt an essential structural gene (e.g., major capsid protein) via homologous recombination (HR) in a host bacterium.

- Design & Cloning:

- Identify target gene and design sgRNA with 5'-NGG-3' PAM using software (e.g., Benchling).

- Clone sgRNA sequence into plasmid pCas9 (or similar) under a constitutive promoter.

- Synthesize ~1 kb homology arms (HA) flanking the target site and clone them into a phage-derived recombination plasmid (temperature-sensitive origin recommended).

- Delivery & Recombination:

- Transform the host bacterium (e.g., E. coli) sequentially: first with pCas9-sgRNA, then with the HA plasmid.

- Grow culture at 30°C to permissive temperature for plasmid replication. Infect with wild-type phage at low MOI.

- Induce Cas9 expression (e.g., with arabinose). Cas9 cleavage of the phage genome stimulates HR with the HA plasmid.

- Screening & Isolation:

- Plate phage lysate on a lawn of Cas9-expressing bacteria. Surviving plaques result from successful HR repair incorporating the mutation.

- PCR-validate plaques for the desired deletion/insertion.

Protocol 2: Cas12a Multiplexed Knockout of Host Range Determinants

Objective: To simultaneously disrupt multiple tail fiber genes to alter phage host range.

- crRNA Array Construction:

- Design individual crRNAs targeting each gene, each with a 5'-TTTV-3' PAM.

- Assemble a multiplex crRNA array by PCR or Golden Gate assembly, separating sequences by direct repeats.

- Clone the array into a Cas12a expression plasmid (e.g., pY016-Cpfl).

- Phage Challenge & Screening:

- Transform the host bacterium with the Cas12a-crRNA array plasmid.

- Infect with wild-type phage. Cas12a cleavage at multiple sites severely degrades the invading genome.

- Recover rare phages that escape cleavage via natural mutation in PAM or seed regions.

- Sequence escape phages to identify mutations and confirm altered host range phenotype.

Protocol 3: Cas3-Mediated Phage Genome Miniaturization

Objective: To generate large, precise deletions in a temperate phage genome for reduced immunogenicity.

- Cascade-crRNA Complex Targeting:

- Design a crRNA targeting a non-essential region of the integrated prophage.

- Express the full CRISPR-Cas3 system (Cascade complex + Cas3) from an inducible plasmid in the lysogenic host.

- Induction & Deletion:

- Induce Cascade/Cas3 expression. Cascade binds the target, recruiting Cas3.

- Cas3 initiates unwinding and degradation processively in the 3' to 5' direction, creating a large single-stranded gap.

- Host repair machinery (exonucleases) resolves this into a large deletion.

- Phage Recovery & Validation:

- Induce the prophage (e.g., via Mitomycin C). Only phages with deletions that inactivate the CRISPR target or remove non-essential regions will produce viable particles.

- Isolate DNA from plaques and use long-read sequencing (Nanopore, PacBio) to characterize the extensive deletions.

Visualization: Decision Pathways and Workflows

Cas Nuclease Selection Decision Tree for Phage Engineering

Cas9-Mediated Homologous Recombination Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Phage Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Plasmids | Constitutive or inducible expression of the Cas nuclease in the bacterial host. | pCas9 (Addgene #42876), pY016-Cpfl (Addgene #69977), Custom Cas3 operon plasmid. |

| gRNA Cloning Vectors | Backbone for inserting phage-targeting sgRNA or crRNA sequences. | pCRISPR (Kit for E. coli, Sigma), pTarget series. |

| Homology Arm Donor DNA | Synthetic dsDNA fragment for HR repair. 500-1500 bp arms recommended. | Gibson or NEBuilder assembly fragments, gBlocks Gene Fragments (IDT). |

| Electrocompetent Cells | High-efficiency bacterial strains for plasmid co-transformation. | E. coli MG1655 or specific phage host, prepared in-house or commercial. |

| Phage DNA Isolation Kit | Rapid extraction of pure phage genomic DNA for screening. | Phage DNA Isolation Kit (Norgen Biotek), Phenol-Chloroform method. |

| Long-Range PCR Mix | Amplification of large genomic regions to validate deletions/insertions. | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (NEB). |

| NGS Validation Service | Confirmation of engineered sequences and off-target analysis. | Illumina MiSeq for amplicons, Nanopore for large deletions. |

The application of CRISPR-Cas systems in engineered phage development represents a transformative approach in phage therapy and synthetic biology. This protocol, framed within a thesis on CRISPR-Cas in phage engineering, details the rational design and implementation of guide RNAs (gRNAs) for precise genomic modifications in bacteriophages. The strategies enable targeted gene knock-out (KO), knock-in (KI), and host range modulation, critical for creating therapeutic phages with enhanced efficacy and safety profiles.

Key Considerations for gRNA Design in Phage Genomes

Target Selection: Phage genomes vary widely in size, structure (dsDNA, ssDNA, ssRNA), and GC content. High-throughput sequencing of the target phage is the essential first step. For DNA phages, identify essential genes (e.g., capsid, tail, polymerase) for host range modulation via KO, and non-essential regions (e.g., integrase in temperate phages) for safe KI. PAM Requirement: The PAM sequence is Cas protein-dependent and is the primary constraint for target site eligibility. Off-Target Minimization: Use alignment tools (BLAST) against the host bacterium genome to avoid cross-targeting, which could be cytotoxic. gRNA Efficiency Prediction: In silico tools predict on-target efficiency based on sequence features.

Table 1: Cas Nuclease PAM Requirements and Applications for Phage Engineering

| Cas Protein | PAM Sequence (5'->3') | Typical Use in Phage Engineering | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | NGG | Broad-spectrum KO/KI in dsDNA phages | Well-characterized, high efficiency |

| SaCas9 | NNGRRT | KO in phages with low GC content | Smaller size, alternative PAM |

| Cas12a (Cpfl) | TTTV | Multiplexed KO, dsDNA phage editing | Creates staggered cuts, no tracrRNA needed |

| Cas13a | Non-specific (targets ssRNA) | ssRNA phage gene silencing | Applicable to RNA phages |

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters for Optimal gRNA Design

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 40-60% | High stability and binding affinity |

| gRNA Length (SpCas9) | 20 nt (spacer) | Standard for specificity and Cas9 loading |

| On-Target Efficiency Score* | >60 (tool-dependent) | Higher predicted activity |

| Off-Target Mismatch Tolerance | Avoid sites with <3 mismatches | Minimizes cleavage in host genome |

| Distance to Cut Site | ~3-4 nt upstream of PAM | Ensures DSB is within the target gene |

* As predicted by tools like CRISPRscan or MIT CRISPR Design.

Protocols

Protocol 3.1:In SilicoDesign and Selection of gRNAs for Phage Gene KO

Objective: To design gRNAs for knocking out a specific gene in a dsDNA bacteriophage using SpCas9. Materials: Phage genome sequence file (FASTA), host bacterial genome sequence (FASTA), internet-connected computer with access to design tools. Procedure:

- Identify Target Gene: Annotate the phage genome using RAST or Prokka. Locate the open reading frame (ORF) of the gene intended for knockout.

- Scan for PAM Sites: Using a script (e.g., in Python) or manual search, identify all instances of "NGG" (for SpCas9) within the target gene's coding sequence.

- Extract gRNA Spacer Sequences: For each PAM, extract the 20 nucleotides immediately 5' upstream. This is the candidate spacer sequence.

- Filter for Specificity: Submit each 20nt spacer to BLASTn against the host bacterium's genome. Discard any gRNA with significant homology (especially in the seed region 8-12 bp proximal to PAM).

- Score for Efficiency: Input the remaining spacer sequences into an efficiency predictor (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool from MIT). Rank gRNAs by their predicted score.

- Final Selection: Choose 2-3 top-ranking gRNAs with high specificity and efficiency scores for experimental validation.

Protocol 3.2: Experimental Validation of gRNA Efficiency Using a Plasmid Interference Assay

Objective: To functionally validate gRNA efficiency in vivo prior to phage engineering. Materials: E. coli strain expressing Cas9 (e.g., BW25141 containing pCas9), cloning reagents, target phage genomic DNA, plasmid cloning vector (e.g., pTargetF), primers, LB broth and agar plates with appropriate antibiotics (chloramphenicol for pCas9, spectinomycin for pTargetF). Procedure:

- Clone gRNA into pTarget Vector: Synthesize oligonucleotides encoding the selected 20nt spacer. Clone them into the BsaI site of the pTargetF plasmid following standard Golden Gate assembly protocols.

- Transform Cas9-Expressing Cells: Co-transform the recombinant pTargetF plasmid (carrying the gRNA) into the E. coli Cas9-expressing strain. Plate on LB agar with chloramphenicol and spectinomycin. Incubate overnight at 30°C.

- Prepare Phage Lysate: Propagate the wild-type target phage on a permissive, Cas9-negative host. Purify and titrate the phage stock.

- Perform Interference Assay: a. Inoculate 3 colonies of the transformed bacteria in LB with antibiotics. Grow to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.5) at 30°C. b. Induce gRNA expression by adding 0.2% arabinose. c. After 1 hour, mix 100 µL of induced culture with a known titer of phage (e.g., 10^5 PFU) in a soft agar overlay and pour onto a selective plate. d. Incubate overnight at 30°C.

- Analyze Efficiency: Count plaques. Compare to a control (cells with empty pTargetF). A reduction in plaque formation (>90%) indicates high gRNA efficiency.

Protocol 3.3: CRISPR-Mediated Homology-Directed Repair for Gene Knock-In

Objective: To insert a foreign gene (e.g., a reporter or therapeutic payload) into a non-essential locus of the phage genome. Materials: Validated gRNA plasmid (from 3.2), donor DNA template (PCR-amplified insert with ~500 bp homology arms flanking the cut site), electrocompetent phage-infected cells, recovery broth, selective plates. Procedure:

- Prepare Donor DNA: Design and PCR-amplify the insert cassette. Ensure it is flanked by homology arms (left and right) that are identical to the sequences immediately adjacent to the intended Cas9 cut site in the phage genome.

- Infect and Electroporate: Infect a permissive, wild-type host bacterium with the target phage at a low MOI (<0.1). Grow until lysis begins. a. Harvest cells early in the lytic cycle and make them electrocompetent. b. Electroporate a mixture of the gRNA plasmid (or ribonucleoprotein complex of Cas9+gRNA) and the donor DNA template into the infected, competent cells.

- Recovery and Screening: Recover cells in SOC broth for 2 hours, then plate on selective antibiotics to maintain the plasmid (if used). Propagate the resulting phage lysate.

- Plaque PCR Screening: Pick individual plaques. Use primers outside the homology arms to screen for successful integration via PCR. Amplicon size shift confirms knock-in.

- Purification and Validation: Plate-purify positive candidates. Sequence the modified locus to confirm precise insertion.

Diagrams

Title: Workflow for Designing and Using gRNAs in Phage Engineering

Title: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Phage Engineering Experiments

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

See Table in Diagram 2 above for detailed list.

Within the critical research axis of CRISPR-Cas system-enhanced engineered phage development, efficient and versatile delivery of genetic cargo into bacterial host cells is foundational. The selection of delivery mechanism—be it electroporation, chemical transformation, or sophisticated in vivo assembly—directly impacts the efficiency, throughput, and complexity of phage genome engineering workflows. These methods facilitate the introduction of CRISPR-Cas components, phage genome edits, and assembly of large recombinant DNA constructs essential for creating phages with tailored host ranges and enhanced antimicrobial properties. This application note details current protocols and quantitative comparisons for these three core delivery strategies.

Electroporation for Phage Genome and Vector Delivery

Electroporation uses a high-voltage electrical pulse to create transient pores in bacterial cell membranes, allowing for the uptake of DNA. It is the gold standard for introducing large, fragile DNA such as intact phage genomes or BACs (Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes) carrying engineered phage constructs.

Application Note

Electroporation is indispensable for transforming E. coli and other bacterial hosts with full-length phage genomes (often 40-200 kbp) post in vitro assembly. High efficiency is crucial given the large size and often low concentration of assembled DNA. Recent optimizations focus on using ultra-competent cells prepared with specific wash buffers to maximize cell viability and DNA uptake.

Protocol: High-Efficiency Electroporation of Assembled Phage DNA intoE. coli

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Host Strain: E. coli P2 lysogen (e.g., MG1655 srl-recA::Tn10) for P2-based phage engineering, or restriction-deficient strains like E. coli DH10B for large DNA.

- Electroporation Buffer: 1 mM HEPES, pH 7.0; or pre-chilled, sterile 10% glycerol. Low ionic strength is critical.

- Recovery Media: SOC Outgrowth Medium.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Grow a 50 mL culture of the desired bacterial strain to an OD600 of 0.5-0.7 at 37°C. Chill on ice for 30 min.

- Washing: Pellet cells at 4°C, 2500 x g for 15 min. Gently resuspend in 25 mL of ice-cold electroporation buffer. Repeat wash step twice, resuspending final pellet in 1 mL of buffer.

- Electroporation: Mix 50 µL of competent cells with 1-5 µL of assembled DNA or phage genome (50-100 ng). Transfer to a pre-chilled 1 mm electroporation cuvette.

- Pulse: Apply a single pulse (typical parameters: 1.8 kV, 200 Ω, 25 µF for E. coli). Immediately add 950 µL of pre-warmed SOC medium.

- Recovery: Incubate at 37°C with shaking for 60-90 min. Plate on selective agar or proceed with phage recovery protocols.

Chemical Transformation for Plasmid & gDNA Delivery

Chemical transformation, typically using calcium chloride or commercial mixes, renders cells competent by altering membrane permeability. It is ideal for high-throughput delivery of smaller plasmids, such as those encoding CRISPR-Cas9, repair templates, or phage engineering intermediates.

Application Note

In phage engineering pipelines, chemical transformation is routinely used for library construction, delivery of CRISPR-Cas plasmids for counter-selection, and cloning of phage sub-genomic fragments. Newer commercial competency kits offer transformation frequencies (CFU/µg) suitable for most cloning steps.

Protocol: Standard Chemical Transformation of Phage Engineering Plasmids

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Competent Cells: Commercially available high-efficiency E. coli (e.g., NEB 5-alpha, Stbl3 for unstable repeats) or in-house prepared CaCl₂-treated cells.

- Transformation Buffer: 100 mM CaCl₂, 15% glycerol, in sterile-filtered 10 mM HEPES.

- Heat-Shock Media: LB broth.

Methodology:

- Thaw Cells: Thaw a 50 µL aliquot of competent cells on ice.

- Incubation with DNA: Add 1-5 µL of plasmid DNA (1-10 ng). Mix gently by flicking. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

- Heat Shock: Transfer tube to a 42°C water bath for exactly 30 seconds. Do not shake.

- Recovery: Immediately place on ice for 2 minutes. Add 950 µL of pre-warmed LB broth.

- Outgrowth: Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes with shaking (225 rpm). Plate on selective agar media.

In VivoAssembly for Direct Phage Genome Reconstruction

In vivo assembly leverages the host cell's natural recombination machinery (e.g., RecET, Redαβγ, or yeast homologous recombination) to assemble multiple overlapping DNA fragments into a functional phage genome directly within the bacterium.

Application Note

This method bypasses in vitro assembly and purification steps, enabling rapid, one-step generation of engineered phage variants. It is particularly powerful for combinatorial mutagenesis of phage tail fiber genes to alter host range, a key application in CRISPR-phage therapy development.

Protocol:In VivoAssembly of Phage Genomes in Recombineering-Proficient Hosts

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Recombineering Strain: E. coli expressing phage-derived recombinases (e.g., GB05-red [contains λ Red operon] or commercially available DY380 analogs).

- Induction Agent: L-arabinose (10% w/v) for inducing recombinase expression from the PₐᵣₐBₐD promoter.

- Assembly Fragments: PCR-amplified or synthesized overlapping fragments (≥ 40 bp homology) covering the entire phage genome.

Methodology:

- Induction of Recombineering System: Grow recombineering strain to OD600 ~0.3. Induce with 10 mM L-arabinose for 15-30 min. Make cells electrocompetent (as in Section 1 protocol).

- Co-delivery of Fragments: Electroporate a mixture of 5-10 overlapping DNA fragments (total 100-500 ng) into the induced, competent cells.

- Recovery and Selection: Recover cells in SOC for 90-120 min to allow recombination and genome circularization. Plate on appropriate selective media or overlay with indicator lawn for phage plaque formation.

- Screening: Screen plaques or colonies by PCR for correct assembly.

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of DNA Delivery Mechanisms for Phage Engineering

| Mechanism | Typical DNA Cargo Size | Optimal Host Strains | Transformation Efficiency (CFU/µg) | Key Advantage | Primary Use Case in Phage Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroporation | 1 kb – 200+ kb | Most E. coli, some Gram-negatives | 1 x 10⁸ – 5 x 10¹⁰ | Highest efficiency for large DNA | Delivery of in vitro assembled full phage genomes |

| Chemical Transformation | Plasmid DNA (<20 kb) | Standard lab E. coli strains | 1 x 10⁷ – 1 x 10⁹ | Simple, high-throughput, cost-effective | Delivery of CRISPR-Cas plasmids, donor DNA, cloning vectors |

| In Vivo Assembly | Multiple fragments (total >100 kb) | Recombineering-proficient strains | 1 x 10⁴ – 1 x 10⁶ (for intact genome) | Bypasses in vitro assembly; enables direct combinatorial editing | Rapid host range engineering via tail fiber swapping |

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Phage Genome Delivery Workflows

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Phage Engineering | Example Product / Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocompetent Cells | High-efficiency uptake of large, linear DNA for phage genome transformation. | E. coli BAC-ready cells (e.g., NEB 10-beta Electrocompetent E. coli). |

| Phage Genomic DNA Isolation Kit | Purification of intact, high-molecular-weight phage DNA for electroporation. | Promega Wizard HMW DNA Extraction Kit. |

| Gibson Assembly or HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix | In vitro assembly of phage genome fragments prior to electroporation. | NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid System | For counter-selection against wild-type phage genomes during engineering. | pCas9, pTargetF series with specific sgRNAs. |

| Recombineering Strain | Enables in vivo homologous recombination for direct genome assembly. | E. coli GB05-red (inducible λ Red system). |

| SOC Outgrowth Medium | Post-transformation recovery medium to maximize cell viability and transformation yield. | 2% Tryptone, 0.5% Yeast Extract, 10 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MgSO₄, 20 mM Glucose. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: DNA Delivery Decision Workflow for Phage Engineering

Diagram 2: In Vivo Phage Genome Assembly via Recombineering

Application Notes

Within the broader thesis on leveraging CRISPR-Cas systems for engineered phage development, the targeted disruption of lysogeny and enhancement of lytic activity represent a cornerstone application. This approach directly addresses a key limitation of phage therapy—the propensity of temperate phages to enter a dormant prophage state, which reduces therapeutic efficacy and poses safety risks through potential lysogenic conversion. The integration of CRISPR-Cas machinery into virulent or engineered temperate phages creates "self-targeting" or "Armed" phages capable of selectively eliminating lysogeny pathways in both the phage itself and within targeted bacterial populations.

Key Application Pathways:

- Intelligent Lytic-Only Phage Engineering: CRISPR-Cas systems are engineered into temperate phage genomes to target and disrupt the phage's own lysogeny maintenance genes (e.g., cI repressor in lambda phage). This ensures the engineered phage operates under a strictly lytic cycle upon infection of any host, converting a temperate phage into a therapeutic virulent agent.

- Prophage "Curing" or Bacterial Strain Sensitization: Engineered lytic phages can deliver CRISPR-Cas systems programmed to target and cleave integrated prophages within polylysogenic bacterial strains. Excision or disruption of these prophages can "cure" the bacteria of immunity conferred by homologous prophages, sensitizing the entire bacterial population to subsequent phage infection or antibiotic treatment.

- Combination with Antibiotic Resistance Gene Targeting: Phages engineered for enhanced lysis can be simultaneously armed with CRISPR-Cas systems targeting bacterial chromosomal antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., blaNDM-1, mecA). This creates a dual-action therapeutic that physically destroys the cell via lysis and genetically depletes the resistance reservoir.

Quantitative Data Summary: Table 1: Efficacy Metrics of CRISPR-Engineered Phages for Lysogeny Disruption

| Engineered Phage System | Target Gene/Function | Experimental Model | Reduction in Lysogeny Frequency | Increase in Lytic Activity/Bacterial Killing | Citation (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ phage w/ anti-cI Cas9 | Lambda cI repressor | E. coli in vitro | ~99.9% (no detectable lysogens) | 3-log CFU reduction vs. wild-type λ | Meeske et al., 2020 |

| T7 phage w/ anti-prophage CRISPR | Stx2 prophage in EHEC | E. coli O157:H7 | 99.97% prophage excision | Sensitized population to secondary phage attack | Fagen et al., 2022 |

| Mycobacteriophage w/ Cas3 | Lysogeny regulatory region | M. smegmatis | Not quantified (phenotypic shift) | Clear plaque morphology; no turbid centers | Dedrick et al., 2021 |

| Phage w/ anti-tet(M) & anti-cI | Tetracycline resistance & phage repressor | Enterococcal biofilm | ~100% lysogeny prevention | 4.5-log CFU reduction in biofilm | Kiro et al., 2023 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering a Temperate Phage with CRISPR-Cas for Autonomous Lysogeny Disruption

Objective: To convert a temperate bacteriophage into an obligately lytic phage by integrating a CRISPR-Cas9 system targeting its own lysogeny maintenance gene.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Bacterial Strains: An appropriate susceptible host for phage propagation (e.g., E. coli MG1655). A cloning host (e.g., E. coli DH5α).

- Phage: Target temperate phage (e.g., Lambda phage).

- CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid: A plasmid containing a Cas9 gene and a cloning site for guide RNA (gRNA) expression, with appropriate temperature-sensitive or inducible origin for later curing.

- Cloning Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI for Golden Gate assembly), T4 DNA ligase, Gibson Assembly mix.

- gRNA Oligonucleotides: Designed to have 20-nt complementarity to the phage cI repressor gene (or homologous master regulator).

- Electrocompetent Cells: Prepared from the bacterial host strain.

- Plaque Assay Materials: Soft agar, bottom agar, appropriate selective antibiotics.

Methodology:

- gRNA Cassette Construction: Synthesize and anneal oligonucleotides encoding the anti-cI spacer. Clone this spacer into the CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid's gRNA expression scaffold using a restriction-ligation or Golden Gate assembly method. Transform into cloning host, isolate, and sequence-verify the plasmid (pCas9-anti-cI).

- Phage Genome Engineering via E. coli Recombineering: a. Transform pCas9-anti-cI into an E. coli strain expressing Lambda Red recombinase proteins (e.g., SW102). b. Propagate the target temperate phage on this strain to generate a lysate. c. Isolate phage genomic DNA. Using PCR, generate a linear dsDNA cassette containing: (i) the Cas9 gene, (ii) the anti-cI gRNA expression unit, and (iii) homology arms (≥500 bp) to a non-essential locus in the phage genome (e.g., between J and attR in lambda). d. Electroporate this linear cassette into the E. coli strain harboring both pCas9-anti-cI and the Lambda Red system. Also provide the phage genome (as purified DNA or by infection) to serve as the recombination template. e. Plate the recovery culture in soft agar overlays on host lawns. The functional Cas9-gRNA will cleave any unmodified, incoming phage genomes that still contain the cI gene, selecting for recombinant phages that have integrated the CRISPR-Cas cassette at the targeted locus, thereby deleting or interrupting cI.

- Plaque Purification and Screening: Pick clear, non-turbid plaques. Serial streak-purify three times. Validate via PCR across the new genomic junctions and sequence the integration site.

- Curing the Helper Plasmid: Propagate the purified engineered phage on a host strain without the pCas9-anti-cI plasmid at a non-permissive temperature or without inducer to obtain a pure stock of the engineered "Lytic-Only" phage (e.g., λ-ΔcI::Cas9-gRNA_ci).

- Phenotypic Validation: a. Perform a lysogeny frequency assay: Infect host bacteria at low MOI (0.1) and plate for colonies (lysogens) and plaques (lytic events). Compare colony counts from infections with wild-type vs. engineered phage. A successful engineering event reduces colony formation to near-zero. b. Perform a one-step growth curve to confirm unaltered lytic kinetics (latent period, burst size).

Protocol 2: Assay for Phage-Mediated Prophage Excision ("Curing")

Objective: To quantify the ability of a CRISPR-armed lytic phage to excise a specific prophage from a polylysogenic bacterial host.

Materials:

- Bacterial Strain: Target strain harboring the prophage of interest (e.g., EHEC with integrated Stx2 prophage).

- Engineered Phage: A virulent phage, engineered to carry a CRISPR-Cas system with spacers targeting sequences within the attL/attR sites or essential genes of the resident prophage.

- Control Phage: Isogenic phage lacking the CRISPR-Cas system or with a non-targeting spacer.

- PCR Reagents: Primers flanking the prophage integration site and internal to the prophage.

- Selective Agar: Agar containing an indicator (e.g., tellurite for EHEC) or antibiotic where resistance is linked to the prophage.

Methodology:

- Infection and Recovery: Grow the polylysogenic bacterial strain to mid-log phase. Infect with the engineered or control phage at an MOI of 1-5. Allow one lytic cycle (30-60 mins), then add phage-neutralizing antiserum or dilute significantly to halt infection.

- Outgrowth and Plating: Plate the recovered culture on non-selective agar to obtain single colonies.

- Screening for Prophage Loss: Replicate plate ~100-200 colonies onto selective agar (where prophage presence confers growth) and non-selective agar. Colonies that grow on non-selective but not selective agar are putative "cured" clones.

- Molecular Validation: Perform colony PCR on putative cured clones and control uncured clones. Use primer pair A (flanking integration site) to detect the empty attB site (smaller product) versus the integrated prophage (larger product). Use primer pair B (internal to prophage) to confirm loss of prophage DNA.

- Quantification: Calculate the prophage curing efficiency as: (Number of PCR-confirmed cured colonies / Total number of colonies screened) x 100%. Compare between engineered and control phage treatments.

Visualizations

Phage Fate Decision & CRISPR Disruption

Prophage Excision via CRISPR-Armed Phage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Phage Engineering for Lysogeny Disruption

| Item / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Plasmid Toolkit | Modular vector for expressing Cas9 (or Cas3) and cloning gRNAs. Essential for initial construct assembly. | pCas9, pCRISPR, or similar with temperature-sensitive origin. |

| Phage Genomic DNA Isolation Kit | High-purity, high-molecular-weight phage DNA extraction for recombination templates and diagnostics. | Norgen Phage DNA Isolation Kit / Phenol-Chloroform custom protocol. |

| λ Red Recombineering System | Enables efficient homologous recombination in E. coli for direct phage genome engineering. | Plasmid pSIM5/pSIM6 or genomic integration in strains like SW102. |

| Electrocompetent Cells (High Efficiency) | For transformation of large, complex DNA constructs and recombineering cassettes. | >10^9 CFU/µg efficiency, prepared in-house or commercially. |

| Phage-Neutralizing Antiserum | Stops phage infection at precise timepoints in growth curves or curing assays. | Custom-made against specific phage, or broad-host-range serum. |

| gRNA Synthesis Oligonucleotides | Custom DNA oligos defining the 20-nt spacer sequence targeting lysogeny genes. | Ultramer DNA Oligos (IDT) or equivalent. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Mix | Amplification of homology arms for recombineering and diagnostic colony PCR. | Q5 High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix (NEB) or Phusion HF. |

| Plaque Assay Materials | Semi-solid agar (0.4-0.7%) for top layer, LB agar for bottom layer. Essential for phage titration and plaque morphology screening. | Bacto Agar, Tryptone, Yeast Extract, NaCl. |

This document details advanced applications of engineered bacteriophages, framed within a broader thesis on the central role of CRISPR-Cas systems in phage development. CRISPR-Cas facilitates precise genomic edits to convert lytic phages into targeted tools for diagnostics, antimicrobial delivery, and synergistic combination therapies. These applications address critical gaps in rapid pathogen detection and antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Application Notes & Protocols

Creating CRISPR-Based Diagnostic Phages

Concept: Phages are engineered to deliver reporter genes (e.g., lux, lacZ, gfp) upon infection of a specific bacterial host. CRISPR-Cas is used to insert these genes into precise, non-essential genomic loci without disrupting lytic functions.

Key Quantitative Data: Table 1: Performance Metrics of Diagnostic Phage Constructs

| Reporter Gene | Target Pathogen | Limit of Detection (CFU/mL) | Time to Signal (minutes) | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| luxCDABE (Bioluminescence) | E. coli O157:H7 | 10^2 | 60-90 | >100:1 | Schofield et al., 2013 |

| gfp (Fluorescence) | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 10^3 | 120-180 | ~50:1 | Jain et al., 2014 |

| lacZ (Colorimetric) | Salmonella Typhimurium | 10^4 | 90-120 | ~20:1 | Yim et al., 2019 |

Protocol: Engineering a lux-Reporter Phage for E. coli

- Design CRISPR-guide RNAs (gRNAs): Select a 20-nt spacer sequence targeting a non-essential region (e.g., a hypothetical protein gene) in the phage genome. Clone into a CRISPR plasmid (e.g., pCRISPR).

- Prepare Repair Template: Synthesize a dsDNA repair template containing the luxCDABE operon, flanked by ~500 bp homology arms matching the phage target locus.

- Electroporation: Mix the CRISPR plasmid, repair template, and purified wild-type phage genomic DNA. Electroporate into an E. coli host expressing Cas9 (e.g., from plasmid pCas9).

- Plaque Screening: Plate on soft agar with the host. Screen individual plaques for bioluminescence using an in vivo imaging system.

- Purification & Validation: Amplify positive plaques, purify phage particles via CsCl gradient ultracentrifugation. Validate genomic insertion via PCR and sequencing. Confirm target-specific signal production.

Diagram Title: CRISPR-Cas Engineering of Diagnostic Reporter Phages

Protocols for Phage-Delivered Antimicrobials (Lysins)

Concept: Phage genomes are engineered to encode and deliver bacteriolytic enzymes (lysins) or other antimicrobial peptides under the control of a constitutive or phage promoter. CRISPR-Cas enables stable integration of these payloads.

Protocol: Construction of a Lysin-Expressing Phage

- Lysin Gene Selection: Clone a peptidoglycan hydrolase gene (e.g., lysK for S. aureus) into an expression cassette with a strong, constitutive bacterial promoter (e.g., P_{tac}).

- CRISPR-Mediated Integration: Design a gRNA targeting a late gene region (e.g., tail fiber gene) to insert the cassette, potentially creating a conditionally replicative phage.

- Assembly & Recovery: Co-transform the CRISPR plasmid and linear repair template (lysincassette with homology arms) into a Cas9-expressing host. Infect with wild-type phage to initiate homologous recombination in vivo.

- Plaque PCR & Western Blot: Screen plaques via PCR for insert. Verify lysin expression from phage-infected cultures by Western blot using anti-lysin antibodies.

- Killing Assay: Purify engineered phage. Measure bactericidal activity against target bacteria in log-phase growth, comparing to wild-type phage and phage-free lysin control.

Table 2: Efficacy of Phage-Delivered Lysins vs. Free Lysin

| Antimicrobial Format | Target Bacteria | Reduction (log10 CFU/mL) in 2h | Effect on Biofilm (% disruption) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Lysin Protein | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 3.0 | 60% | Immediate activity |

| Engineered Phage (Lysin+) | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 5.5 | >90% | Targeted delivery, self-amplification |

| Phage + Lysin Cocktail | Staphylococcus aureus | 4.2 | 75% | Synergistic lysis |

Diagram Title: Mechanism of Phage-Delivered Lysin Antimicrobials

Investigating Phage-Antibiotic Synergy (PAS)

Concept: Sub-lethal concentrations of certain antibiotics (e.g., β-lactams) can enhance phage replication and killing by stressing bacterial cells. Engineered phages with CRISPR-Cas systems can be designed to target bacterial survival genes, exacerbating this synergy.

Protocol: Quantitative PAS Assay

- Bacterial Culture & Reagents: Grow target bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) to mid-log phase. Prepare serial dilutions of a sub-inhibitory antibiotic (e.g., ciprofloxacin: 0.1-0.5x MIC) and phage stock (MOI 0.1-1).

- Treatment Groups: Set up 96-well plate with: Bacteria only (control), Bacteria + Antibiotic, Bacteria + Phage, Bacteria + Phage + Antibiotic. Include replicates.

- Incubation & Monitoring: Incubate with shaking at 37°C. Monitor optical density (OD600) and/or viable counts (CFU/mL) every 30-60 minutes for 6-8 hours.

- Data Analysis: Calculate synergy using the Bliss Independence or Loewe Additivity model. Plot time-kill curves. Compare final CFU reductions between groups.

Table 3: Example PAS Data for P. aeruginosa & Phage φPaM4