Ensuring Accuracy in Viral Detection: A Comprehensive Guide to Nucleic Acid Extraction Quality Control

This article provides a comprehensive overview of quality control (QC) strategies for viral nucleic acid extraction, a critical pre-analytical step that directly impacts the sensitivity and reliability of downstream molecular...

Ensuring Accuracy in Viral Detection: A Comprehensive Guide to Nucleic Acid Extraction Quality Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of quality control (QC) strategies for viral nucleic acid extraction, a critical pre-analytical step that directly impacts the sensitivity and reliability of downstream molecular diagnostics and research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content explores the foundational importance of QC, details the application of internal and external controls, addresses common challenges like inhibition and contamination, and presents comparative data on extraction methods. By synthesizing current research and methodologies, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to implement robust QC protocols, thereby ensuring data integrity in applications ranging from clinical diagnostics to viral metagenomics.

Why Extraction Quality Control is the Bedrock of Reliable Viral Diagnostics

The Critical Impact of Extraction Efficiency on Downstream Assay Sensitivity

Extraction efficiency is a cornerstone of reliable molecular diagnostics, directly influencing the sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility of downstream assays such as PCR and next-generation sequencing. In viral nucleic acid testing, inefficient extraction can lead to false negatives, inaccurate viral load quantification, and compromised research outcomes. This technical resource center provides researchers and laboratory professionals with targeted troubleshooting guides and evidence-based protocols to identify, resolve, and prevent extraction-related issues that impact assay performance.

Core Concepts: Extraction Efficiency and Assay Sensitivity

What is Extraction Efficiency and Why is it Critical?

Extraction efficiency refers to the percentage of target nucleic acid successfully recovered from a sample during the extraction process. [1] It is a critical parameter in analytical chemistry and molecular biology, directly impacting the accuracy, precision, and reliability of downstream analytical results. [1] In the context of viral nucleic acid extraction, this translates to the complete recovery of viral RNA or DNA from complex biological matrices such as plasma, saliva, semen, or swab samples.

The relationship between extraction efficiency and assay sensitivity is fundamental: a failure to efficiently isolate nucleic acids introduces preanalytical variability that no downstream assay can overcome. [2] When extraction efficiency is low, the starting template for amplification is reduced, thereby increasing the limit of detection and raising the probability of false-negative results, particularly in samples with low viral load. [3] This is especially crucial in clinical diagnostics, where missing low-level infections can have significant patient management implications.

Key Factors Influencing Extraction Efficiency

Multiple technical and biological factors contribute to the variability in extraction efficiency:

- Sample Matrix Effects: Complex biological fluids contain inherent inhibitors. Semen contains PCR inhibitors from seminal plasma and extender components. [3] Saliva has variable viscosity and high RNase activity. [4] These matrix components can reduce nucleic acid extraction efficiency and sensitivity. [3]

- Extraction Methodology: Different extraction principles (silica-membrane, magnetic beads, anion exchange) exhibit varying size-specific binding efficiencies. [2] For example, one study found reproducible extraction efficiencies of 84.1% (± 8.17) for a plasma cfDNA kit, 58.7% (± 11.1) for a urine kit, and 30.2% (± 13.2) for an in-house Q Sepharose protocol. [2]

- Fragment Size Selectivity: Extraction methods often display bias toward specific fragment sizes. Methods can selectively lose shorter fragments (<100 bp), which is particularly problematic for urinary cfDNA and microRNA analysis. [2]

- Technical Execution: Manual pipetting introduces variability through human error, while automated systems standardize liquid handling but require proper calibration and maintenance to perform consistently. [5] Worn equipment components can also create process inconsistencies. [6]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Extraction Problems and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Yield | - Consistently low nucleic acid concentration- Poor amplification in downstream assays- High Ct values in qPCR | - Incomplete cell lysis- Suboptimal binding conditions- Sample over-digestion- Excessive nucleic acid loss during washing | - Optimize lysis conditions (e.g., add proteinase K, DTT) [3]- Verify binding buffer pH and composition- Include carrier RNA to improve recovery [4]- Reduce wash steps or volumes [4] |

| PCR Inhibition | - Delayed amplification in internal controls- Reaction failure- Inconsistent standard curves | - Co-purification of inhibitors (heme, polysaccharides, salts)- Incomplete removal of chaotropic salts- Carryover of organic solvents | - Incorporate sample pretreatment steps [3]- Use inhibitor removal reagents or columns- Dilute template and re-amplify- Include a PCR inhibition assay in validation [7] |

| Inconsistent Results | - High well-to-well variability- Poor reproducibility between operators- Inconsistent extraction efficiencies | - Manual pipetting errors [5]- Improper mixing of samples with reagents- Uneven heating during lysis or elution- Equipment calibration drift [6] | - Implement automated liquid handling [5]- Standardize mixing protocols and incubation times- Establish regular equipment maintenance schedules [6]- Use spike-in controls to normalize for efficiency [2] |

| Size Bias | - Underrepresentation of short fragments in downstream analysis- Altered fragment size profile compared to expected | - Methodological bias against short fragments [2]- Silica membrane retention thresholds- Bead-based size selection effects | - Select extraction methods validated for short fragments [2]- Evaluate alternative binding conditions (e.g., PEG concentration)- Use methods specifically designed for cell-free DNA or microRNAs |

Quantitative Data: Comparing Extraction Performance

Documented Extraction Efficiencies Across Methods and Sample Types

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from recent studies, providing benchmark data for expected extraction efficiencies.

Table 1: Extraction Efficiency Metrics from Published Studies

| Extraction Method | Sample Type | Target | Extraction Efficiency | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit [2] | Plasma | 180 bp spike-in (CEREBIS) | 84.1% (± 8.17) | High and reproducible efficiency for plasma cfDNA; considered a reference method |

| Zymo Quick-DNA Urine Kit [2] | Urine | 180 bp spike-in (CEREBIS) | 58.7% (± 11.1) | Moderate efficiency; showed different size selectivity compared to other methods |

| Q Sepharose (Qseph) protocol [2] | Urine | 180 bp spike-in (CEREBIS) | 30.2% (± 13.2) | Lower efficiency but better recovery of shorter fragments (<90 bp) |

| Insta NX Mag 16Plus with HiPurA Cartridges [8] | Plasma (spiked) | HBV DNA | LOD: 2.39 IU/μL | Validated with WHO international standards; suitable for high-sensitivity viral load testing |

| POC-Pure Custom Method [4] | Saliva | SARS-CoV-2 RNA | LOD: <0.5 copies/μL | Cost-effective, wash-free method optimized for point-of-care salivary diagnostics |

Impact of Technical vs. Biological Variability

Understanding the sources of variation in your workflow is crucial for effective troubleshooting. A variance component analysis reveals where attention should be focused.

Table 2: Relative Contribution to Total Variance in cfDNA Quantification [2]

| Experimental Setup | Largest Variance Component | Secondary Variance Component | Minor Variance Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Setup (Pooled Plasma) | Intra-extraction measurement (ddPCR triplicates) | Inter-extraction variability | Inter-operator and inter-day variability |

| Biological Setup (Individual Samples) | Inter-individual biological variability | Inter-extraction variability | Intra-extraction measurement variability |

Key Insight: While technical optimization is vital, biological variability often constitutes the largest source of total variance. [2] This underscores the importance of appropriate experimental design and sample size.

Experimental Protocols for Extraction Efficiency Evaluation

Protocol 1: Assessing Extraction Efficiency Using Synthetic Spike-ins

The use of non-human, artificially synthesized DNA spike-ins allows for precise quantification of extraction recovery without risk of contamination from natural sources. [2]

Principle: A known quantity of synthetic nucleic acid (e.g., CEREBIS - Construct to Evaluate the Recovery Efficiency of cfDNA extraction and BISulphite modification) is spiked into the sample prior to extraction. [2] The recovery is quantified after extraction using digital PCR (ddPCR) for absolute quantification.

Materials:

- CEREBIS spike-in DNA (e.g., 180 bp and 89 bp fragments) [2]

- Test samples (plasma, urine, etc.)

- Extraction kit/method to be validated

- Droplet Digital PCR system and reagents

- Specific primers/probes for the spike-in sequence

Procedure:

- Spike: Add a known copy number of CEREBIS (e.g., CER180bp) to an aliquot of the sample. Include a no-spike negative control.

- Extract: Process the spiked sample through the entire extraction workflow alongside an unspiked control.

- Quantify: Measure the concentration of the recovered CEREBIS in the eluate using ddPCR.

- Calculate: Extraction Efficiency (%) = (Measured copies after extraction / Initial copies added) × 100.

Troubleshooting Note: The spike-in should closely resemble the target analyte in size to account for the size-specificity of extraction methods. [2] Using multiple spike-ins of different lengths (e.g., 89 bp and 180 bp) can help characterize size bias.

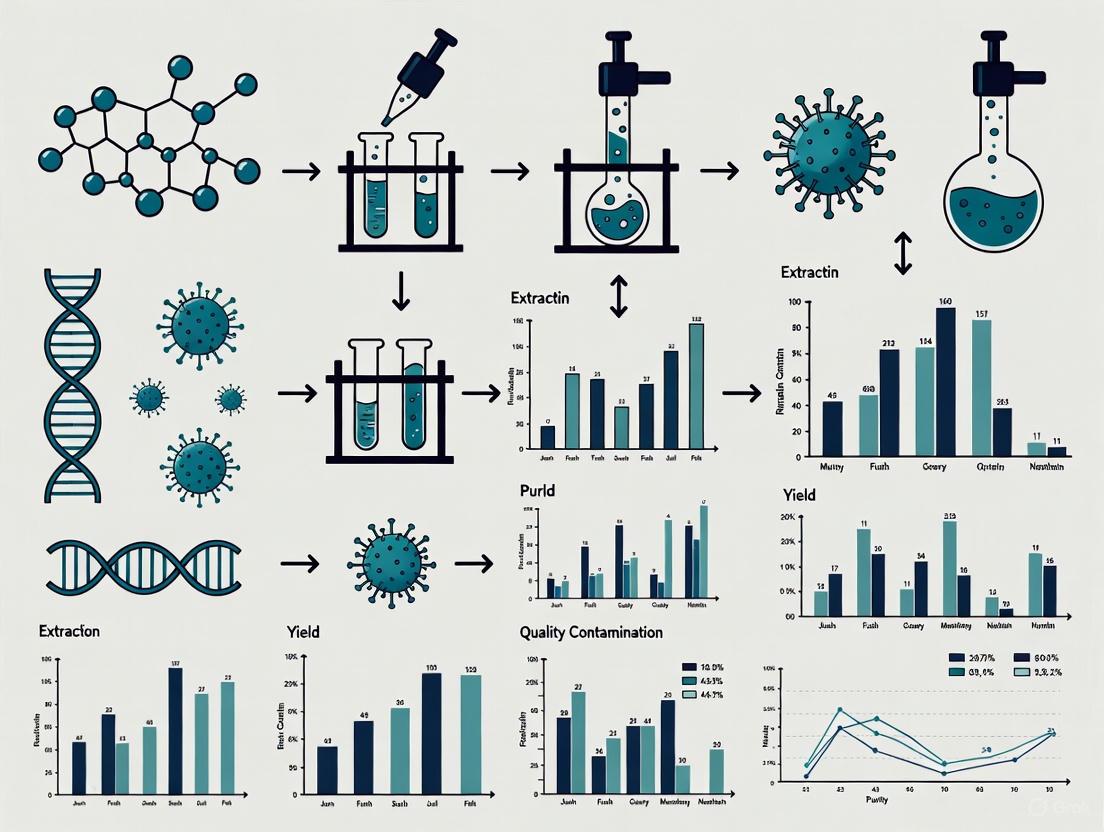

Workflow: Spike-in Normalization for Extraction Efficiency

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for using a synthetic spike-in to assess and normalize for extraction efficiency:

Protocol 2: Evaluating PCR Inhibition in Extracted Samples

Co-purified inhibitors can severely impact downstream assay sensitivity even when extraction yield appears adequate. [7] This protocol provides a direct test for their presence.

Principle: A known quantity of exogenous control DNA is added to the extracted sample and amplified via qPCR. The cycle threshold (Ct) shift compared to a control reaction in water indicates the level of inhibition.

Materials:

- Eluted nucleic acids from the test extraction

- Exogenous control template (non-competitive, e.g., from a different species)

- qPCR master mix and specific primers/probes for the control

- qPCR instrument

Procedure:

- Prepare Inhibition Test: Set up a qPCR reaction containing the eluted test sample (e.g., 5 µL) spiked with the control template.

- Prepare Control: Set up an identical qPCR reaction containing nuclease-free water (instead of sample) spiked with the same amount of control template.

- Amplify: Run qPCR under standard cycling conditions.

- Analyze: Compare the Ct values of the inhibition test and the control.

- No Inhibition: ΔCt (Test - Control) ≈ 0

- Significant Inhibition: ΔCt > 1-2 cycles, indicating PCR suppression.

Interpretation: A significant ΔCt suggests the presence of inhibitors in the extract. Optimization of the extraction protocol, such as additional wash steps or the use of inhibitor removal reagents, is required. [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CEREBIS Spike-in [2] | Synthetic, non-human DNA to evaluate extraction and bisulphite conversion recovery. | Designed to mimic mononucleosomal cfDNA (~180 bp); contains cytosine-free regions for bisulphite conversion control. |

| Guanidine Hydrochloride (GuHCl) [4] | Chaotropic salt that denatures proteins and facilitates nucleic acid binding to silica. | Preferred over GuSCN for some POC applications as trace amounts (<140 mM) can enhance LAMP amplification efficiency. |

| Magnetic Silica Beads [8] [9] | Solid phase for nucleic acid binding and purification in automated high-throughput systems. | Core component of many automated extraction systems (e.g., Insta NX Mag 16Plus); enable reproducible, high-quality isolation. |

| Proteinase K [3] | Broad-spectrum serine protease that digests nucleases and other contaminating proteins. | Critical for efficient lysis of tough structures (e.g., viral capsids, semen); often used in pretreatment steps. |

| VetMAX Xeno Internal Positive Control RNA [3] | Exogenous RNA control added to lysis buffer to monitor both extraction efficiency and PCR inhibition. | Distinguishes between extraction failure and the presence of PCR inhibitors in the final eluate. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My extraction yields are good based on spectrophotometry, but my qPCR sensitivity is poor. What is the most likely cause? This discrepancy often indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors in your extract or a size bias in your extraction method. Spectrophotometry (A260) can overestimate DNA concentration in the presence of RNA or other contaminants. [7] Run a PCR inhibition assay and check the A260/A230 ratio; values below 1.8-2.0 can indicate polysaccharide or salt contamination, which are common inhibitors. [7] Also, confirm your extraction method efficiently recovers the specific fragment size of your target.

Q2: When should I consider normalizing my results for extraction efficiency? Normalization is highly recommended in the following scenarios:

- When comparing absolute quantities of nucleic acids between samples extracted with different methods. [2]

- When working with challenging sample matrices known to cause variable recovery (e.g., urine, semen, formalin-fixed tissues). [2] [3]

- In clinical applications where accurate viral load quantification is critical for patient management. [8]

- When your data shows that technical (extraction) variability is a significant component of the total variance. [2]

Q3: What are the key advantages of automated extraction systems over manual kits? Automated systems offer enhanced reproducibility, reduced human error, and higher throughput. [8] [5] They standardize critical parameters like incubation times and mixing, minimizing inter-operator and inter-batch variability. This is crucial for generating reliable and reproducible data in both research and clinical diagnostics. Automated systems also reduce hands-on time and the risk of cross-contamination. [8]

Q4: How can I improve extraction efficiency from inhibitor-rich samples like semen or saliva?

- Implement a Pretreatment Step: Use proteinase K, DTT (for viscous samples), and detergents (e.g., SDS) with heating to break down complex matrices. [3]

- Optimize Input Volume: Counterintuitively, reducing the sample input volume can sometimes improve purity and efficiency by reducing the inhibitor load. [3]

- Add Carrier RNA: Including carrier RNA during lysis can improve the recovery of low-copy-number viral RNA by providing bulk for more efficient silica binding. [4]

- Select Specialized Kits: Use extraction kits specifically validated or optimized for your challenging sample type.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of PCR inhibitors in different sample types?

PCR inhibitors can originate from various components present in clinical and environmental samples. The common sources and their mechanisms of action include:

- Clinical Samples: Heme from blood can block the active site of the DNA polymerase. Bilirubin, bile salts, and complex polysaccharides from stool can also inhibit polymerase activity. Proteases can degrade the enzyme itself, while IgG antibodies can bind to single-stranded DNA [10] [11].

- Environmental Samples: Humic acids and fulvic acids from soil and sediments can interfere with the PCR reaction [10].

- General Components: Urea (e.g., from urine) and EDTA from collection tubes can chelate magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), which are essential co-factors for DNA polymerase function [12] [10].

Q2: Why might my positive control amplify perfectly, but my target reaction from the same sample extract fail?

This is a classic symptom of differential inhibition. Different PCR reactions can have vastly different susceptibilities to the same inhibitor [12]. Research has shown that a substance co-purified from a sample can completely inhibit one PCR assay while leaving another unaffected. This means the internal control and your target assay are not "inhibition compatible," leading to false negatives for your target even when the control suggests the reaction is fine [12].

Q3: My nucleic acid extraction kit claims to remove inhibitors, but my PCR is still inefficient. What could be wrong?

Even the best extraction kits can have variable efficiency. A study comparing four different commercial RNA extraction kits from the same manufacturer found significant differences in their ability to remove inhibitors and produce usable sequence data for downstream Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [13]. Furthermore, some inhibitors can co-elute with the nucleic acids during purification, evading the removal steps of the kit [10]. The selection of the extraction method itself has a major impact on the yield and the number of viral reads in NGS analysis [13].

Q4: Are there specific reagents that can make my PCR more resistant to inhibitors?

Yes, several inhibitor-resistant PCR reagents are commercially available. However, their performance is highly dependent on the sample matrix. The table below summarizes the performance of various chemistries across different sample types, demonstrating that no single solution works best for all matrices [10].

Table 1: Performance of Inhibitor-Resistant PCR Reagents Across Different Matrices

| Chemistry Name | Manufacturer | Best Performing Matrices | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phusion Blood Direct PCR Kit | New England Biolabs | Whole Blood | Designed for direct amplification from difficult samples [10]. |

| Phire Hot Start DNA Polymerase | New England Biolabs | Whole Blood | An enhanced polymerase for challenging samples [10]. |

| Phire Hot Start + STR Boost | New England Biolabs | Whole Blood, Soil | The only reagent to yield a low limit of detection in soil [10]. |

| KAPA Blood PCR Kit | KAPA Biosystems | Multiple | Not the best in any one matrix, but showed the most consistent results across various conditions [10]. |

| Omni Klentaq | DNA Polymerase Technology | Blood, Soil | Reported to amplify targets from samples containing up to 20% whole blood or soil [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Consistently High Ct Values or PCR Failure Across Multiple Samples

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Inefficient Nucleic Acid Extraction.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your extraction kit. Protocols optimized for simultaneous extraction of viral and bacterial nucleic acids have been developed and validated on clinical samples. These often combine mechanical disruption (e.g., bead-beating) with enzymatic lysis (e.g., lysozyme for gram-positive bacteria) and the use of carrier RNA to improve recovery of low-concentration viral nucleic acids [14]. Ensure you are using a kit appropriate for your sample type, as extraction efficiency significantly impacts downstream analysis [13].

Cause: Inhibitors Co-purifying with Nucleic Acids.

- Solution A (Pre-treatment): Dilute the template DNA/RNA. This dilutes the inhibitor but also dilutes the target, which may not be suitable for low-abundance targets [10].

- Solution B (Additives): Add inhibitor-binding or -resistant agents to the PCR mix. These include:

- Solution C (Specialized Reagents): Use one of the inhibitor-resistant polymerases or master mixes listed in Table 1 [10].

Problem: Successful Amplification in Some Sample Types but Failure in Others

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Sample-Specific Inhibitors.

- Solution: Tailor your approach to the sample. For example, Phire Hot Start DNA polymerase with STR Boost was particularly effective for direct detection in soil, while other kits performed better in blood [10]. You cannot assume a protocol that works for blood will work for sputum or soil.

Cause: Differential Inhibition.

- Solution: If using an internal control, you must validate that it is compatible with your target assay. This means that both reactions should be inhibited to the same degree by potential inhibitors in your sample extracts [12]. If they are not, a negative result for your target cannot be trusted.

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Replicates of the Same Sample

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Incomplete or Inconsistent Lysis.

- Solution: Ensure your lysis protocol is robust and reproducible. For tough samples like gram-positive bacteria or tissue, this may require a combination of methods. A developed protocol for simultaneous extraction uses bead-beating followed by an enzymatic cocktail (e.g., lysozyme) and then a chemical lysis step with buffer AL and proteinase K to ensure complete breakdown of cells and viral envelopes [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Overcoming PCR Inhibition

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Carrier RNA | Improves the recovery and yield of viral RNA during extraction by acting as a binding carrier for minute amounts of nucleic acids. | Added during the proteinase K step to significantly improve detection of low-copy-number viruses like influenza [14]. |

| Inhibitor-Resistant Polymerase | Engineered DNA polymerases or specialized buffers designed to remain active in the presence of common PCR inhibitors. | Phire Hot Start DNA Polymerase with STR Boost for direct detection of pathogens in whole blood or soil without extensive sample purification [10]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein additive that binds to certain inhibitors (e.g., polyphenols, humic acids) in the PCR mixture, preventing them from inactivating the polymerase. | Added to PCR reactions to neutralize inhibitors in complex samples like plant extracts or soil [10]. |

| Lysozyme | An enzyme that breaks down the cell walls of gram-positive bacteria, which are otherwise difficult to lyse. | Essential in a simultaneous extraction protocol to ensure the release of bacterial DNA from organisms like Staphylococcus aureus [14]. |

| Zirconia/Silica Beads | Used in mechanical lysis (bead-beating) to physically disrupt tough cell walls or spores for nucleic acid release. | Critical for efficient lysis of gram-positive bacteria in a protocol designed for concurrent viral and bacterial nucleic acid extraction [14]. |

Experimental Workflow & Inhibition Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for handling inhibitory samples and the points where inhibitors commonly disrupt the process.

In the field of viral diagnostics and research, the quality of nucleic acid extraction is a pivotal pre-analytical factor that directly influences the sensitivity and accuracy of downstream molecular assays such as qPCR and RT-PCR. This technical guide details the core quality control (QC) metrics—extraction yield, purity, and inhibitor presence—providing researchers with standardized methodologies for assessment and troubleshooting. Within the context of viral nucleic acid extraction, rigorous QC is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement for reliable genomic data, ensuring that results from pathogen detection, drug development, and viral load quantification are both valid and reproducible.

Nucleic acid extraction is the first critical step in any molecular diagnostic experiment, and its efficiency is paramount for successful downstream applications [15]. The process involves isolating, purifying, and concentrating nucleic acids from complex biological matrices, which can include various inhibitors and contaminants [16] [15]. For viral nucleic acids specifically, which are often present in low copies in environmental or clinical samples, the challenge is even greater [17]. Inhibitors co-purified during extraction can cause partial or complete inhibition of enzymatic reactions in PCR or reverse transcription, leading to false-negative results and an underestimation of viral presence [17] [18]. Therefore, establishing a robust QC protocol to assess extraction yield, sample purity, and the absence of inhibitors is a non-negotiable standard in viral research.

Essential QC Metrics and Their Assessment

The following core metrics provide a comprehensive picture of your nucleic acid sample's quality and suitability for downstream applications.

Extraction Yield

Definition: Extraction yield refers to the quantity of nucleic acid recovered from a given volume of starting sample. A high yield is particularly crucial for detecting low-copy-number viral targets.

Assessment Methods:

- UV Spectrophotometry: This is a common first-pass method. The concentration of nucleic acid is determined by measuring its absorbance at 260 nm (A260). A reading of 1.0 corresponds to approximately 40 μg/mL for single-stranded RNA and 50 μg/mL for double-stranded DNA [19].

- Fluorometric Methods: Using DNA- or RNA-binding fluorescent dyes provides a more specific quantification than UV spectrophotometry, as it is less affected by the presence of contaminants [20].

Purity

Definition: Purity indicates the level of contamination from other molecules, such as proteins, residual chemicals from the extraction process, or other nucleic acids.

Assessment Methods:

- UV Absorbance Ratios: This is the primary method for assessing purity.

- A260/A280 Ratio: This ratio evaluates protein contamination. For pure DNA, a ratio of ~1.8 is expected, while for pure RNA, a ratio of ~2.1 is expected [19]. A significantly lower ratio suggests residual protein. For example, an A260/A280 reading of 1.8 for an RNA sample indicates about 70–80% protein content, which can inhibit PCR [18].

- A260/A230 Ratio: This ratio assesses contamination by organic compounds (e.g., phenol, chaotropic salts like guanidine) or chaotropes. A ratio of 2.0 or higher is generally acceptable [19].

- Advanced Spectral Profiling: Next-generation spectrophotometers can "unmix" the absorption spectra of a sample to differentiate between DNA, RNA, and common impurities, providing a more accurate assessment of purity [20].

Presence of Inhibitors

Definition: Inhibitors are substances that co-purify with nucleic acids and interfere with downstream enzymatic reactions like reverse transcription or PCR, potentially causing false-negative results.

Common Inhibitors:

- From the sample: Hemoglobin, heparin, polysaccharides, humic acids (in environmental water samples), and bile salts [18] [15].

- From extraction: Phenol (>0.2% w/v), SDS (>0.01% w/v), ethanol (>1%), guanidinium, and salts [18].

Assessment Methods:

- Inhibition Plots (Standard Curve Analysis): Semi-log standard curves from real-time PCR data can be used to characterize inhibition. A shift in the curve compared to a control indicates inhibition [18].

- Use of Internal Controls:

- Control Virus Particles: Adding a known quantity of a control virus (e.g., murine norovirus, adenovirus) to the sample prior to nucleic acid extraction allows for the direct evaluation of extraction efficiency and the identification of nucleic acid loss during the process [17].

- Primer-Sharing Controls (PSC): These are synthetic controls that share the same primer-binding sequences and amplicon size as the target viral nucleic acid but have a different probe sequence. They are added to the sample post-extraction, just before amplification, to specifically evaluate the presence of PCR inhibitors without the confounding variable of extraction loss [17].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

This section addresses specific issues researchers may encounter during viral nucleic acid extraction.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Yield

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Homogenization/Lysis | Inefficient cell/viral particle disruption; inadequate lysis buffer, time, or conditions [21]. | Use an appropriate lysis buffer with detergents (e.g., SDS); optimize lysis conditions (pH, temperature, duration); employ mechanical methods like bead beating or sonication [21]. |

| Inefficient Binding to Matrix | Inadequate mixing with binding buffer; presence of contaminants; suboptimal pH or salt concentration; overloading the column or beads [21]. | Ensure proper mixing of sample and binding buffer; use binding buffers with chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine); optimize binding buffer pH (lower pH favors binding to silica) [21] [22]. |

| Nucleic Acid Degradation | Presence of nucleases (DNases/RNases) during extraction or storage [21]. | Use nuclease-free reagents and equipment; add RNase inhibitors for RNA work; avoid excessive vortexing to prevent mechanical shearing; store samples properly [21] [18]. |

| Low Elution Volume/ Efficiency | Elution buffer volume not optimized; insufficient incubation during elution [21]. | Optimize elution buffer volume for starting material; let the column/beads incubate with elution buffer for a few minutes; consider using pre-warmed (60-70°C) elution buffer to increase yield [21]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Poor Purity and Inhibition

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Contamination | Proteins not effectively removed during extraction [21]. | Use proteinase K treatment; perform an additional chloroform extraction step; use phase-lock gel tubes to partition proteins away [21]. |

| Chemical Contamination (Phenol, Salts) | Incomplete washing steps; residual reagents from lysis or binding buffers [18] [20]. | Perform the recommended number of washes with the appropriate wash buffer; ensure wash buffers flow through completely; use wash buffers containing ethanol or other competitive agents [21]. |

| Co-purified Inhibitors (e.g., Humic Acid) | Common in environmental samples (water, soil); silica-based methods may not always remove them effectively [17]. | Use extraction methods with guanidinium thiocyanate, which is excellent at denaturing proteins and removing inhibitors [22]. For water samples, a magnetic silica bead-based method has been shown to effectively remove inhibitors [17]. |

| Carryover of Organic Solvents | Incomplete phase separation in phenol-chloroform extraction [21]. | Ensure proper mixing and centrifugation speed/duration for effective phase separation [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My RNA sample has an A260/A280 ratio of 1.8. Is it suitable for RT-qPCR? A: This ratio suggests significant protein contamination (approximately 70-80% protein in the sample), which can inhibit both reverse transcription and PCR [18]. It is recommended to further purify the sample by phenol-chloroform extraction, LiCl precipitation, or using a purification kit designed to remove proteins before proceeding.

Q2: My extraction yield is good, but my PCR fails. What is the most likely cause? A: This is a classic sign of PCR inhibition. The sample likely contains co-purified contaminants that inhibit polymerase activity. Assess inhibition using a primer-sharing control or inhibition plot [17] [18]. Further purify the sample or dilute the template to a concentration where inhibitors no longer affect the reaction [18].

Q3: For critical viral detection, should I prioritize yield or purity? A: Both are critical, but the context matters. For low-abundance viral targets, a high yield is essential to ensure the target is present in the aliquot used for testing. However, if the sample is impure, the inhibitors can prevent detection even if the target is present. Therefore, the optimal strategy is to use a high-yield extraction method that also includes robust wash steps to ensure purity [22]. Incorporating internal controls to monitor both extraction efficiency and amplification inhibition is considered best practice [17].

Q4: What is the most rapid nucleic acid extraction method that still maintains good QC metrics? A: Recent advancements have led to the development of very rapid methods. For instance, a magnetic silica bead-based method called SHIFT-SP can be completed in 6-7 minutes while showing similar or superior DNA yield compared to commercial methods taking 25-40 minutes [22]. Another study developed a five-minute extraction method (FME) for respiratory viruses that yielded superior RNA concentration and purity compared to traditional methods and showed high clinical coincidence rates [23]. The key to adopting any rapid method is to rigorously validate its yield, purity, and freedom from inhibitors for your specific sample type.

Experimental Protocols for Key QC Assessments

Protocol: Assessing Extraction Efficiency Using Internal Controls

This protocol allows for the differentiation between nucleic acid loss during extraction and inhibition of the amplification reaction [17].

- Spike-in Control Addition: Prior to nucleic acid extraction, add a known quantity of a non-interfering control virus (e.g., adenovirus type 5 or murine norovirus) to the environmental or clinical sample.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Proceed with your chosen extraction method.

- qRT-PCR Quantification: Perform qRT-PCR targeting both the viral pathogen of interest and the spiked-in control virus.

- Calculation: Calculate the extraction efficiency by comparing the measured quantity of the control virus to its known input quantity. A significant drop indicates low extraction efficiency.

Protocol: Assessing RT-PCR Inhibition Using Primer-Sharing Controls (PSC)

This protocol specifically evaluates the presence of substances that inhibit the amplification reaction itself [17].

- PSC Design: Synthesize a control nucleic acid that has the same primer-binding sequences and amplicon size as your target virus, but a different internal probe sequence.

- Addition: Add a known quantity of this PSC to the purified nucleic acid sample after extraction, just before setting up the RT-PCR reaction.

- Amplification: Run the multiplex qRT-PCR assay with probes for both the target and the PSC.

- Analysis: A significant increase in the cycle threshold (Ct) value for the PSC compared to its performance in a clean background (e.g., water) indicates the presence of RT-PCR inhibitors in the sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Nucleic Acid Extraction and QC

| Reagent / Material | Function in Viral NA Extraction |

|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidinium Isothiocyanate) | Denature proteins and nucleases, inactivate viruses, and facilitate the binding of nucleic acids to silica matrices [22] [19]. |

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Solid-phase matrix for binding nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropes; enable automation and rapid separation via a magnetic field [22] [15]. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that digests and removes contaminating proteins from the sample [19]. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Essential for RNA work to protect labile RNA molecules from degradation by ubiquitous RNases [19]. |

| Control Virus Particles (e.g., Murine Norovirus) | Exogenous spikes to monitor and quantify the efficiency of the nucleic acid extraction process from the sample [17]. |

| Primer-Sharing Controls (PSC) | Internal amplification controls to detect the presence of inhibitors in the purified nucleic acid eluate [17]. |

Workflow: Identifying QC Failure Points

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing the root cause of a failed downstream application, such as a negative PCR result from a sample suspected to contain a virus.

Diagram: A logical workflow for troubleshooting nucleic acid quality issues.

In the field of molecular diagnostics and viral metagenomics, the reliability of downstream results is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the initial nucleic acid extraction. Inadequate quality control (QC) during this critical step can lead to severe consequences, including false negative diagnoses and compromised research data, ultimately undermining public health responses and scientific conclusions. A 2021 study emphasized that establishing QC measures for the extraction of viral nucleic acids is a persistent challenge, yet it is essential for the stable detection of pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 [24]. The selection of an extraction method has a major impact on the yield and the number of viral reads obtained in next-generation sequencing (NGS), directly influencing the sensitivity and reliability of viral detection [13]. This guide details the troubleshooting procedures and quality control measures necessary to ensure the integrity of your viral nucleic acid workflows.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can inadequate nucleic acid extraction lead to false negatives in viral detection? False negatives occur when the viral pathogen is present in a sample but goes undetected. A primary reason for this is the inefficient lysis of viral particles or poor recovery of nucleic acids during extraction, leading to a yield that falls below the detection limit of subsequent PCR or sequencing assays. Research has shown that different extraction kits exhibit vastly different efficiencies for the same virus. For instance, a metagenomic study of respiratory samples found that the threshold cycle (Ct) values for viruses like human parainfluenza virus 3 (PIV3) and adenovirus (ADV) varied significantly across four different Qiagen kits. One kit revealed the lowest detectability for HMPV and PIV3, potentially increasing the risk of a false negative result [13].

Q2: Beyond false negatives, how else can poor extraction compromise my data? Compromised data integrity can manifest in several ways:

- Biased Metagenomic Results: Inefficient extraction can drastically alter the apparent viral community in a sample. The same study demonstrated that the percentage of viral reads in NGS data could range from as low as 0.03% with some kits to 9.61% with another, fundamentally changing the metagenomic profile [13].

- Reduced Sensitivity for NGS: Inadequate QC can lead to insufficient quantity or quality of input nucleic acid for library preparation. The Translational Genomics Lab specifies minimum quality standards, such as using fluorometers (e.g., Qubit Flex) for accurate quantity and instrumentation (e.g., Agilent TapeStation) for quality assessment, which are crucial for successful NGS [25].

- Introduction of Inhibitors: Incomplete removal of contaminants during the washing steps of extraction can co-elute with the nucleic acids. These substances can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions like reverse transcription and PCR, leading to unreliable data [26].

Q3: What are the key challenges when extracting from complex sample types like saliva or feces? Complex samples present unique hurdles that can undermine QC:

- Viscosity: Plasma and saliva are difficult to pipette accurately and can lead to clogging of tips, resulting in sample volume errors and inconsistent binding [26].

- Inhibitors: Fecal samples contain substances like humic acids that are potent PCR inhibitors. Failure to address this during extraction will compromise downstream detection [26].

- Variable Biomass: The high and variable biomass in feces makes consistent pipetting difficult. It is recommended to use around 50mg per extraction for better consistency, even if the kit protocol supports higher amounts [26].

Q4: What is a simple internal control method I can implement for my extraction workflow? Incorporating an extrinsic quality control substance is an effective strategy. As published in J Clin Lab Anal., a control substance is added to the sample at the beginning of the process. Real-time RT-PCR is then performed, and the results are tracked using quality control charts. This method allows for continuous monitoring of the entire process—from nucleic acid extraction to detection—ensuring stability and reliability even when different technicians or extraction methods are used [24].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem: Low Nucleic Acid Yield from Viscous Samples (e.g., Plasma, Saliva)

- Potential Cause 1: Incomplete mixing during the lysis or binding steps, leading to inefficient release and binding of nucleic acids.

- Solution: Visually ensure that a complete vortex forms and that magnetic particles (if used) are fully suspended during mixing steps. Pipette mixing can be used but is less efficient [26].

- Potential Cause 2: Clogging of pipette tips due to fibrin clots or debris in the sample.

- Solution: Use wide-bore pipette tips designed for viscous samples. Centrifugation or filtration of the sample prior to extraction can also help remove debris [26].

- Potential Cause 3: The extraction kit is not optimized for the sample type.

- Solution: Optimize the protocol by including a Proteinase K digestion step to degrade proteins and improve lysis. Diluting saliva samples can also facilitate mixing [26].

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Technicians or Batches

- Potential Cause: A lack of standardized QC monitoring.

- Solution: Implement the use of an extrinsic quality control substance and generate quality control charts. This provides an objective measure of performance across different operators and over time, allowing for the early detection of process drift [24].

Problem: High Background or Inhibitor Carryover in Fecal Extractions

- Potential Cause: Incomplete washing of bound nucleic acids, or the starting biomass is too high.

- Solution: Ensure magnetic particles are fully resuspended during each wash step. Consider adding an extra wash step to improve purity. For consistency, use a lower, standardized mass of fecal material (e.g., 10-20% mass-to-volume) rather than the maximum the kit allows [26].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Protocol: Establishing an Internal QC Method for Stable Nucleic Acid Extraction

This protocol is adapted from a published study that established a robust QC method for SARS-CoV-2 detection, a framework applicable to viral nucleic acid extraction in general [24].

1. Principle: An extrinsic quality control substance is added to clinical samples. The entire process—from nucleic acid extraction to real-time RT-PCR detection—is monitored, and the results are recorded in a quality control chart to ensure stable and reliable performance.

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- Extrinsic Quality Control Substance (e.g., non-infectious viral particles or synthetic controls)

- Commercial Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (e.g., from Qiagen, Thermo Fisher, or Promega)

- Real-time RT-PCR Reagents

- Thermal Cycler

- Laboratory Centrifuge and Vortex Mixer

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. Add a predetermined, consistent amount of the extrinsic QC substance to your clinical samples (e.g., nasopharyngeal swab transport media).

- Step 2: Nucleic Acid Extraction. Perform nucleic acid extraction according to your established laboratory protocol or kit instructions.

- Step 3: Real-time RT-PCR. Amplify the extracted nucleic acids, including targets specific to the QC substance.

- Step 4: Data Analysis and Charting. Record the Ct values obtained for the QC substance. Plot these values on a quality control chart over time (e.g., a Levey-Jennings chart) to establish a baseline mean and standard deviation.

4. Quality Control: The process is considered "in control" as long as the QC substance's Ct values fall within established control limits (e.g., ±2SD or ±3SD). Any trend or data point outside these limits indicates a problem in the workflow that requires investigation.

Summarized Experimental Data

Table 1: Impact of Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit on Downstream NGS Results from a Mixed Respiratory Sample [13]

| Extraction Kit | Effectiveness Rate of NGS Data | % of Viral Reads (Metagenomic Analysis) | Performance Note (from qRT-PCR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (RPMK) | 67.47% | 9.61% | Highest Ct values for ADV/OC43 (lowest yield) |

| RNeasy Mini Kit (RMK) | 26.79% | ~0.03% | Lowest detectability for HMPV/PIV3 |

| QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin Kit (MVSK) | 12.10% | ~0.03% | Lowest Ct values for ADV/PIV3 (highest yield) |

| QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (VRMK) | 21.27% | ~0.03% | Lower Ct values for multiple viruses |

Table 2: Essential Instruments for Nucleic Acid Quality Control [25]

| Instrument | Function in QC | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Thermo Scientific Qubit Flex Fluorometer | Accurate quantification of nucleic acid concentration. | Distinguishes between DNA, RNA, and dsDNA; more specific than spectrophotometry. |

| Agilent TapeStation 4200 | Assessment of nucleic acid integrity and size distribution. | Detects RNA degradation, checks cfDNA fragment size, and validates NGS libraries. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagent Kits for Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction and Their Applications

| Kit Name | Technology | Primary Sample Types | Key Feature / Rationale for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| PureLink Viral RNA/DNA Mini Kit [27] | Silica Spin Column | Cell-free plasma, serum, cerebrospinal fluid | Recovers both viral RNA and DNA; ideal for RT-PCR and qPCR. |

| MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit [27] | Magnetic Beads | Swabs, saliva, stool, plasma, serum | Easily automated; provides high, consistent yields; suitable for NGS. |

| GeneJET Viral DNA/RNA Purification Kit [27] | Silica Spin Column | Plasma, serum, nasal swab, saliva, urine | Fast and easy isolation of viral nucleic acids from diverse sample types. |

| Maxwell RSC Fecal Microbiome Kit [26] | Magnetic Beads / Automated | Fecal samples, swabs | Effectively removes PCR inhibitors common in complex fecal samples. |

Workflow Visualization: From Inadequate QC to Consequences

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway of how failures at specific quality control checkpoints in the viral nucleic acid extraction process lead to the ultimate consequences of false negatives and compromised data.

Implementing Effective QC Strategies: Controls, Reagents, and Protocols

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are Primer-Sharing Controls (PSCs) and how do they differ from other internal controls?

Primer-Sharing Controls (PSCs) are specialized internal controls designed to be amplified by the same primer pairs as your target viral nucleic acid, resulting in amplicons of the same size [17]. This design is crucial because it means the PSC experiences the same amplification efficiency as the target, even when inhibition occurs [17]. Unlike other controls that might use different primer sequences or produce different amplicon sizes, PSCs most accurately mimic the behavior of your target DNA or RNA during amplification, providing a more reliable assessment of reaction inhibition [17] [28].

Why is my process control showing abnormal Ct values despite successful nucleic acid extraction?

Abnormal Ct values in process controls can stem from several issues. If the Ct is higher than expected, it may indicate inefficient mixing during binding steps, incomplete lysis of viral particles, or the presence of residual inhibitors affecting polymerase activity [26] [17]. Conversely, unusually low Ct values might suggest cross-contamination between samples or degradation of the control material itself. Systematic tracking using quality control charts can help identify whether the issue is random or represents a shift in your overall process [29].

How can I troubleshoot low nucleic acid yield from viscous samples like saliva or plasma?

Low yield from viscous samples often relates to inefficient mixing or incomplete lysis [26]. For saliva samples, which are highly viscous and contain food particles, solutions include: centrifugation after lysis to remove debris, sample dilution to facilitate mixing, use of wide-bore pipettes to handle viscosity, and incorporating proteinase K digestion to degrade proteins and improve viral particle lysis [26]. For plasma, which can contain clots and fibrin, ensuring adequate centrifugation during preparation and using specialized pipette tips with wider openings can prevent clogging and improve yield [26].

Can I use the same internal control for both DNA and RNA viruses?

This depends on the control design. Some process controls like the equine arteritis virus (EAV) RNA control are specifically designed for RNA viruses and reverse transcription steps [29]. However, you can implement separate controls for DNA and RNA targets within the same experimental setup. The key is ensuring that any control you use undergoes the exact same extraction and amplification steps as your target virus. For laboratories detecting multiple virus types, establishing a comprehensive quality control system with appropriate controls for each target type is recommended [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Failed PSC Amplification

Table: Troubleshooting PSC Amplification Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No PSC amplification | PCR inhibitors present, inadequate nucleic acid extraction, reagent degradation | Add competitive agents like BSA or PVP; use magnetic silica bead-based extraction; prepare fresh reagents [17] |

| Inconsistent PSC results across samples | Variable extraction efficiency, improper mixing, sample-specific inhibitors | Implement vigorous mixing; visually confirm magnetic particle suspension; add wash steps [26] [17] |

| PSC amplifies but targets do not | Higher inhibition sensitivity for targets, lower target concentration, sequence issues | Use PSC to quantify inhibition; concentrate sample; verify target integrity [17] |

Step-by-Step Resolution:

- Verify Extraction Efficiency: Spike control virus particles (e.g., adenovirus, murine norovirus) prior to extraction to distinguish between extraction failures and amplification inhibition [17].

- Assess Inhibition: Use your PSC to determine if the issue is specific to certain sample types (e.g., fecal samples with humic acids) [17].

- Optimize Protocol: For inhibitory samples, implement additional purification steps, such as an extra wash in magnetic bead-based methods [26].

- Confirm Reagent Integrity: Prepare fresh reagents and ensure proper storage conditions for enzymes and primers.

Guide 2: Addressing Process Control Variability in Automated Systems

Table: Troubleshooting Process Control Variability

| Issue | System Impact | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent magnetic bead mixing | Variable nucleic acid binding | Implement speed variation during mixing; ensure complete particle suspension [30] |

| Clogged tips with viscous samples | Low and variable yield | Use wide-bore tips; optimize liquid class definitions; add pre-filtration steps [26] |

| Heating step inconsistencies | Lysis or elution efficiency | Verify heating block temperature uniformity; optimize temperature for lysis (95°C) and elution (65°C) [30] |

Systematic Approach:

- Establish Baseline Performance: Run your process control repeatedly under optimal conditions to establish expected Ct values and variability [29].

- Implement Quality Control Charts: Create X-bar control charts with upper and lower control limits (typically mean ± 3SD) to monitor process stability over time [29].

- Identify Variation Patterns: Use the control charts to distinguish between random variation and systematic shifts requiring intervention.

- Validate Improvements: After implementing corrections, confirm they resolve the issue by demonstrating a return to stable control values.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing PSCs for Viral Detection in Environmental Water Samples

Background: This protocol adapts the methodology from Ishii et al. for assessing inhibitory effects on viral genome detection in challenging matrices like environmental waters [17].

Reagents and Equipment:

- Chemically synthesized PSC DNA/RNA with identical primer binding sites and amplicon size as target

- Control virus particles (e.g., adenovirus type 5, murine norovirus)

- Magnetic silica bead-based nucleic acid extraction kit

- RT-PCR or qPCR reagents

- Thermal cycler with real-time detection capability

Procedure:

- PSC Design: Design PSCs to have the same sequence as the target amplicon except for the probe recognition sequence, which should be replaced with a unique sequence [17].

- Sample Processing: Add control virus particles and PSCs to environmental water samples prior to nucleic acid extraction.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Perform extraction using magnetic silica bead-based method to effectively remove inhibitors [17].

- Amplification: Conduct RT-PCR using the same primer pairs for both target and PSC, with different probes for differentiation.

- Analysis: Calculate nucleic acid extraction efficiency from control virus particles and RT-PCR inhibition from PSC results.

Validation: The success rate for satisfactorily amplifying viral RNAs and DNAs by RT-PCR was higher than that for obtaining adequate nucleic acid preparations, confirming that nucleic acid loss during extraction rather than RT-PCR inhibition more significantly attributed to underestimation of viral genomes [17].

Protocol 2: Quality Control Implementation for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

Background: Based on the work by Saito et al., this protocol uses an extrinsic quality control substance and control charts to ensure reliability throughout the nucleic acid testing process [29].

Reagents and Equipment:

- EAV (equine arteritis virus) RNA Extraction Control

- Nucleic acid extraction system (manual or automated)

- Real-time RT-PCR reagents for target and control

- Quality control charting software or spreadsheet

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Add EAV control to clinical samples (10μl for conventional extraction, 6μl for automated systems) prior to extraction [29].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Perform extraction using chosen method (column-based or magnetic bead-based).

- Multiplex Detection: Amplify using multiplex PCR with primers for both SARS-CoV-2 targets and the EAV control.

- Data Collection: Record Cp (crossing point) values for both target and control amplifications.

- Quality Assessment: Plot EAV Cp values on control charts with upper and lower limits (mean ± 3SD) to monitor process stability.

Validation: This approach demonstrated coefficient of variation (CV) of 0.94-2.02% in the N assay and 1.14-1.96% in the N2 assay, indicating high precision even when different technicians performed the extractions [29].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Internal Control Implementation

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Primer-Sharing Controls (PSCs) | Evaluate RT-PCR inhibition with same primers as target | Environmental monitoring; clinical detection of enteric viruses [17] |

| EAV RNA Extraction Control | Quality control for entire extraction and detection process | SARS-CoV-2 detection; respiratory virus panels [29] |

| Magnetic silica bead-based kits | Effective nucleic acid purification with inhibitor removal | Inhibitory samples (feces, water); automated high-throughput systems [17] [30] |

| Proteinase K | Improves lysis efficiency of viral particles | Viscous samples (saliva, serum); high-biomass samples [26] |

| Guanidinium thiocyanate | Chaotropic agent for nucleic acid binding | Lysis buffer component; enhances nucleic acid binding to silica [26] |

Experimental Workflows

Workflow 1: Comprehensive Quality Control Implementation

Workflow 2: Nucleic Acid Extraction Optimization Path

In the field of molecular diagnostics, particularly for viral detection, ensuring the accuracy of every step—from nucleic acid extraction to final amplification—is paramount. External controls, such as the Equine Arteritis Virus (EAV), are non-host molecules added to a sample to monitor the entire testing workflow. Unlike internal controls that are co-amplified with the target, external controls are separate substances that help researchers distinguish between assay failure and a true negative result. Their use is critical for validating test results, meeting regulatory standards, and maintaining high-quality research, especially within the context of viral nucleic acid extraction quality control [31] [32]. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices for integrating these essential tools into your experiments.

Implementing EAV Controls in Your Workflow

Experimental Protocol for EAV Control

The following methodology is adapted from a published study on quality control for SARS-CoV-2 detection, which utilized the Lightmix Modular EAV RNA Extraction Control Kit (Roche Diagnostics) [31].

1. Principle: An extrinsic control substance (EAV control) is added to the clinical sample. Successful detection of the EAV signal via real-time RT-PCR confirms that both the nucleic acid extraction and the amplification detection processes have functioned correctly [31].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Clinical sample (e.g., nasopharyngeal swab).

- EAV control reagent (e.g., from Roche Diagnostics).

- Nucleic acid extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit for manual column extraction or reagents for an automated system like magLEAD 6gC).

- Real-time RT-PCR master mix (e.g., QuantiTect Probe RT-PCR Kit).

- Primers and probes for your target virus and the EAV control.

- Real-time PCR instrument (e.g., COBAS Z480 PCR Analyzer).

3. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Add a specified volume of the EAV control directly to the sample or lysis buffer. The manufacturer typically recommends 10 µL, but this can be optimized; for example, one study used 6 µL for an automated extraction system to maintain the Crossing Point (Cp) value within the recommended range [31].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Co-extract nucleic acids from the patient sample and the EAV control using your chosen method (conventional or automated). The EAV RNA is extracted alongside the target nucleic acids.

- Real-Time RT-PCR Setup: Perform a multiplex real-time RT-PCR reaction. The reaction should include:

- Primers and probes for the viral target(s) (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 N and N2 genes).

- Primers and probes specific for the EAV sequence.

- The extracted nucleic acid template.

- Thermal Cycling: Use conditions appropriate for your RT-PCR kit and assays. An example profile is [31]:

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 30 min

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 15 min

- 45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 sec

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 60 sec

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Cp (Crossing Point) value for both the target and the EAV control. The EAV Cp value should fall within a pre-defined, validated range (e.g., 27-33 cycles as recommended by the manufacturer) [31].

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Establishing a Quality Control Chart

For long-term process stability, create a quality control (QC) chart using the EAV control Cp values to monitor assay performance over time [31].

- Method: Plot the EAV Cp values from successive runs on an X-bar control chart.

- Calculation: Calculate the mean (ˉx) and standard deviation (SD) of the EAV Cp values from at least 20 runs. Establish Upper and Lower Control Limits (UCL/LCL) typically at mean ± 3SD [31].

- Interpretation: Data points outside the UCL/LCL indicate a process that may be out of control and require investigation. The chart below summarizes quantitative data from a study that implemented this system.

Table 1: Performance Data of EAV Control in SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Assays

| Extraction Method | Assay Target | Number of Samples (N) | Mean Cp (Cycle) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Coefficient of Variation (CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | N Gene | 16 | 28.42 | 0.27 | 0.94% |

| Conventional | N2 Gene | 16 | 28.52 | 0.32 | 1.14% |

| Automated | N Gene | 101 | 28.45 | 0.58 | 2.02% |

| Automated | N2 Gene | 101 | 28.62 | 0.56 | 1.96% |

Source: Adapted from [31]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Implementing External Controls

| Item | Function | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EAV Control Reagent | Extrinsic control to monitor entire RNA extraction and amplification workflow. | Lightmix Modular EAV RNA Extraction Control Kit (Roche Diagnostics) [31]. |

| Multiplex RT-PCR Master Mix | Enzyme mix supporting simultaneous amplification of target and control sequences. | QuantiTect Probe RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN) [31]. Must be compatible with multiplexing. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of pure viral nucleic acids (RNA/DNA) from samples. | QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (manual), or reagents for automated systems like magLEAD 6gC [31]. |

| Commercial External Quality Controls (QAPs) | Ready-to-use, commutable controls to verify assay performance across platforms. | Microbix QAPs (available for respiratory, STI, and GI panels), provided in liquid or swab formats [32]. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction System | Instrument for standardized, high-throughput nucleic acid purification. | Systems from vendors like QIAGEN, Roche, Thermo Fisher, and Tianlong. The market is projected to grow to \$11.31B by 2029 [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: The EAV control failed to amplify (no Cp value) in my run. What should I investigate?

- Check the reagent integrity: Confirm the EAV control was stored correctly and is not expired.

- Review pipetting accuracy: Ensure the EAV control was added to the sample. Verify that no pipetting errors occurred during reaction setup.

- Inspect the RT-PCR master mix: Confirm the master mix was prepared correctly and is active. Test with a known positive control if available.

- Examine extraction reagents: Ensure the extraction reagents were not degraded and the protocol was executed properly.

Q2: The EAV Cp value is consistently outside the accepted range (e.g., too high). What does this indicate?

- A high Cp value indicates reduced efficiency in either the extraction or amplification steps. Your troubleshooting should focus on:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Check for expired reagents, clogged columns (in manual methods), or improper handling of magnetic beads (in automated systems). A slight loss of efficiency during extraction can delay the EAV detection.

- PCR Inhibition: Check for the presence of inhibitors in the sample that might affect the PCR efficiency. Consider diluting the eluted nucleic acid or using purification methods to remove inhibitors.

- Deterioration of PCR Reagents: Check the real-time RT-PCR reagents, especially the polymerase enzyme, for loss of activity.

Q3: How do I handle a situation where the EAV control is acceptable, but my positive control fails?

- This scenario strongly suggests a problem specific to the detection of the target, not the overall process.

- Troubleshoot the target-specific reagents: Check the primers and probes for the positive/target control for degradation or errors in reconstitution/dilution.

- Verify the positive control material: Ensure the positive control template is viable and was added correctly.

Q4: What are the key considerations when selecting a source for external control data or reagents?

- When using external controls for clinical research, regulators emphasize that data must be "fit for purpose" [34]. Key factors include:

- Commutability: The control should behave like a real patient sample across different testing platforms [32].

- Data Quality and Relevance: For real-world data (RWD), the source (e.g., registry, EHR) must be well-documented, with patients that closely match your study population in terms of demographics, disease status, and treatment history [35] [34].

- Regulatory Compliance: For in-vitro diagnostics (IVD), ensure controls are manufactured under a Quality Management System like ISO 13485 and have necessary approvals (e.g., FDA, CE mark) for your region [32].

Q5: Are there alternatives to EAV for an extraction control?

- Yes. While EAV is a well-established option, many commercial providers offer panels of external quality controls formulated with whole-genome pathogens or synthetic materials for various diseases (Respiratory, STI, Gastrointestinal panels) [32]. The choice depends on your target pathogen and assay requirements. Furthermore, historical control data from prior clinical trials or real-world databases can serve as external controls in clinical research, though this requires sophisticated statistical methods to account for population differences [35] [36].

Within viral nucleic acid extraction quality control research, the choice of purification methodology is a critical determinant of success. The integrity, yield, and purity of isolated nucleic acids directly influence the reliability of downstream applications, from diagnostic PCR to next-generation sequencing (NGS). This technical support center provides a structured comparison of the three dominant platforms—spin column, magnetic bead, and automated systems—to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and optimizing their workflows. The following guides and FAQs address specific, common experimental challenges encountered in the pursuit of high-quality viral nucleic acids.

Technology Comparison: Core Principles and Performance Metrics

The two foundational chemistries for viral nucleic acid extraction are silica-based binding (used in both spin columns and many magnetic bead protocols) and magnetic particle-based reversible immobilization. Automated platforms typically leverage one of these chemistries within a robotic workflow.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Extraction Methods [37] [27] [38]

| Feature | Spin Column | Magnetic Beads | Automated Platforms (Bead-based) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Principle | Silica membrane in a column that binds DNA/RNA in high-salt buffer [27]. | Silica-coated magnetic beads bind nucleic acids; separated via a magnet [37] [27]. | Robotic systems automating magnetic bead or column protocols [39]. |

| Typical Recovery Yield | 70-85% [37] | 94-96% [37] | Comparable to manual bead methods (when optimized) |

| DNA Size Range | 100 bp – 10 kb [37] | 100 bp – 50 kb [37] | Flexible, based on bead chemistry used. |

| Throughput | Low to medium (manual handling) [38] | High (easily scalable to 96-well plates) [37] | Very High (96, 384 samples per run) [39] |

| Automation Compatibility | Low (requires centrifugation/vacuum) [37] | High (inherently suited to liquid handlers) [37] [40] | N/A (Fully or semi-automated) |

| Hands-on Time | High (manual centrifugation) [38] | Minimal (no centrifugation) [38] | Minimal ("walk-away" time) [41] |

| Cost per Sample | ~$1.75 [37] | ~$0.90 [37] | Higher initial instrument cost; lower per-sample labor cost. |

| Best Suited For | Low-throughput, cost-conscious labs; simple protocols [38]. | High-throughput labs, automated workflows, and applications requiring high yield [37]. | High-volume testing facilities (hospitals, CROs) requiring reproducibility and throughput [42] [39]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my DNA/RNA yield low after a magnetic bead extraction? Low yield in magnetic bead protocols can stem from several factors:

- Bead Over-drying: If the magnetic beads are over-dried after the ethanol wash, it becomes difficult to resuspend them and elute the nucleic acids. Elute promptly after the 3-5 minute air-dry step [37].

- Incomplete Binding or Elution: Ensure proper and thorough mixing during the binding and elution steps. In automated workflows, visually confirm that a complete vortex forms and beads are fully suspended [26].

- Incorrect Bead-to-Sample Ratio: Using an incorrect ratio can lead to inefficient binding or unintended size selection. Adhere to the kit's recommended ratio (e.g., a 1.8x ratio is common for standard cleanups) [37] [41].

Q2: My downstream PCR from spin column extracts is inhibited. What could be the cause? Inhibition often results from carryover of contaminants.

- Residual Ethanol or Wash Buffers: Ensure the final spin is performed with the column removed from the collection tube to avoid re-introducing wash buffer. Extend the spin time or perform a brief "empty" spin after elution to remove residual liquid [37].

- Incomplete Lysis: For complex samples like saliva or feces, the lysis step may be inefficient. Adding a digestion step with Proteinase K can improve lysis of viral particles and degrade proteins that can inhibit downstream reactions [26].

Q3: How can I improve the consistency of my automated extractions from viscous samples like plasma or saliva? Viscous samples pose a significant challenge for automated liquid handling.

- Sample Pre-treatment: Centrifugation of saliva and plasma samples helps remove cellular debris and contaminants. For saliva, dilution or the use of collection reagents can also reduce viscosity [26].

- Liquid Class Optimization: On automated instruments, use or develop a dedicated liquid class for viscous fluids (often starting from a "blood" default). This adjusts pipetting parameters like speed and delay to ensure accurate volume transfers [26].

- Use of Wide-Bore Tips: Employing wide-bore pipette tips can prevent clogging and improve aspiration and dispensing accuracy for viscous liquids [26].

Q4: When should I consider moving from a manual to an automated platform? Automation should be considered when:

- Your lab consistently processes a high volume of samples (dozens to hundreds per day) [38] [39].

- Reproducibility and reduction of human error are critical, such as in clinical diagnostics or regulated drug development [40].

- The goal is to reduce hands-on time and free up skilled personnel for other tasks [41].

Visual Workflow Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the core procedural steps and decision points for the spin column and magnetic bead methods, highlighting key differences that impact workflow efficiency.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction [27] [41] [26]

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffer | Breaks open viral particles, releases nucleic acids, and denatures proteins. Often contains chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine thiocyanate) and detergents. | Must be optimized for sample type (e.g., saliva, feces). Compatibility with downstream assays is critical. |

| Binding Buffer | Creates conditions (e.g., high salt/PEG) that promote nucleic acid binding to silica surfaces (in columns or on beads). | The bead-to-sample ratio in bead-based protocols affects the size range of fragments retained [37]. |

| Proteinase K | An enzyme that digests proteins, improving lysis efficiency and reducing carryover of enzymatic inhibitors. | Essential for high-protein samples (serum, saliva) and difficult-to-lyse samples [26]. |

| Wash Buffer | Typically an ethanol-based solution used to remove salts, enzymes, and other impurities from the bound nucleic acids. | Residual ethanol must be completely evaporated as it can inhibit downstream reactions [37]. |

| Elution Buffer | A low-salt buffer (e.g., TE) or nuclease-free water used to release purified nucleic acids from the silica matrix. | Using a buffer instead of water can enhance nucleic acid stability, especially for long-term storage. |

| Magnetic Beads | Silica-coated paramagnetic particles that reversibly bind nucleic acids. The core technology for bead-based and automated methods. | Bead quality and size distribution are vital for consistent binding, washing, and elution. |

| RNase/DNase-free Consumables | Tips, tubes, and plates that are certified nuclease-free. | Critical for preserving the integrity of RNA and DNA, especially in sensitive applications like qPCR and NGS. |

Detailed Protocol for Magnetic Bead-Based Viral RNA Extraction

This protocol is adapted for a manual, high-yield workflow that can be readily scaled and automated.

Sample Lysis:

- Combine up to 200 µL of viral sample (e.g., plasma, serum, or saliva) with an equal volume of Lysis Buffer and 20 µL of Proteinase K in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Vortex thoroughly and incubate at 56°C for 10-15 minutes to ensure complete viral lysis. For saliva samples, a subsequent centrifugation step to pellet debris is recommended [26].

Nucleic Acid Binding:

- Add 1.8x volumes of Magnetic Beads to the lysate. For example, add 360 µL of beads to 200 µL of lysate [37] [41].

- Mix thoroughly by pipetting or vortexing to ensure the nucleic acids contact the beads.

- Incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes to allow binding.

Washing:

- Place the tube on a magnetic stand until the solution clears and the beads form a pellet (~2-5 minutes). Carefully aspirate and discard the supernatant [37].

- With the tube on the magnet, add 500 µL of freshly prepared 80% ethanol. Incubate for 30 seconds, then aspirate and discard the ethanol. Important: Do not disturb the bead pellet.

- Repeat the wash step a second time.

- After removing the final ethanol wash, air-dry the bead pellet for 3-5 minutes at room temperature. Caution: Over-drying can reduce elution efficiency [37].

Elution:

- Remove the tube from the magnetic stand.

- Resuspend the dried beads in 30-50 µL of Nuclease-Free Water or Elution Buffer by pipetting up and down.

- Incubate at room temperature for 2 minutes.

- Place the tube back on the magnetic stand until the solution clears (~2 minutes).

- Transfer the supernatant, which contains the purified viral RNA, to a new nuclease-free tube. The extract is now ready for downstream analysis.

In viral diagnostics and research, the success of downstream applications like PCR, sequencing, and viral load analysis depends entirely on the quality of the extracted nucleic acids. A robust Quality Control (QC) workflow, from sample lysis to elution, is fundamental to ensuring accurate, reliable, and reproducible results. This guide addresses common challenges and provides troubleshooting protocols to help researchers establish a QC framework that guarantees the integrity of their viral nucleic acid extracts, directly supporting advancements in viral research and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Nucleic Acid Extraction

Q1: What are the primary indicators of incomplete cell lysis, and how can they be distinguished from other issues like contamination?

Incomplete lysis often manifests as lower-than-expected yields because the nucleic acids are not fully released from the viral particles or host cells. It can be distinguished from contamination or degradation by a combination of factors: while contamination might show unexpected bands in electrophoresis, and degradation appears as smearing, incomplete lysis primarily results in low concentration readings without other purity flags, provided the lysis buffer itself was not contaminated. Inefficient lysis can often be traced to the lysis buffer composition, insufficient incubation time, or the presence of inhibitory substances in the original sample [43] [44].

Q2: How does the choice between manual spin-columns and automated magnetic bead systems impact a QC workflow?

The choice fundamentally shapes the QC strategy. Manual spin-column methods are susceptible to user-driven inconsistencies, such as variations in centrifugation force or wash buffer handling, requiring stringent procedural controls. Automated magnetic bead systems, like the Insta NX Mag 16Plus, enhance reproducibility by standardizing mixing, incubation, and washing steps, thereby reducing human error [8] [15]. This automation is critical for high-throughput environments where consistency across hundreds of samples is paramount. Furthermore, automated systems often integrate more seamlessly with laboratory information management systems (LIMS) for robust data tracking [45].

Q3: Why is the internal control (IC) spiked into the lysis buffer, and what factors require its amount to be adjusted?

The internal control is spiked at the initial lysis stage to monitor the entire extraction process, including lysis efficiency, nucleic acid binding, washing, and elution. If the IC fails to amplify in a downstream qPCR, it indicates a process failure. The amount of IC must be optimized based on:

- The expected elution volume.

- The sample type and its potential inhibitors (e.g., heme in blood, bile in stool), which can affect extraction efficiency.