Ensuring Reliability: A Comprehensive Guide to Viral Assay Precision and Linearity Validation

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate the precision and linearity of viral assays.

Ensuring Reliability: A Comprehensive Guide to Viral Assay Precision and Linearity Validation

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to validate the precision and linearity of viral assays. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and comparative validation techniques, it synthesizes current best practices from diverse assays including microneutralization, digital PCR, and multiplex serology. The content is designed to guide professionals in developing robust, reliable, and regulatory-compliant viral detection and quantification methods essential for vaccine development, viral load monitoring, and clinical diagnostics.

Core Principles: Understanding Precision and Linearity in Viral Assays

Troubleshooting Guide: Validation Parameters for Viral Assays

Q1: What are the key validation parameters I need to evaluate for a quantitative viral assay, and what do they mean?

For a quantitative viral assay, especially one based on qPCR, you must evaluate a core set of parameters to ensure the reliability, accuracy, and precision of your results. These parameters are critical for supporting preclinical and clinical safety assessments [1]. The definitions below are aligned with standards from organizations like the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI).

- Precision: The closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under the prescribed conditions [2]. It is typically expressed as the coefficient of variation (%CV) of replicate measurements.

- Linearity: The ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of the analyte in the sample within a given range [2]. For qPCR, the relationship is between the log of the concentration and the threshold cycle (Cq) value.

- Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ): The lowest amount of measurand in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with stated acceptable precision and stated acceptable accuracy, under stated experimental conditions [3] [2]. It is the lowest point on your standard curve that can be reliably measured.

- Upper Limit of Quantification (ULOQ): The highest amount of analyte in a sample that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy. It defines the upper end of the linear range of your assay.

Q2: How do I experimentally determine the LLOQ for my qPCR-based viral assay?

The LLOQ should be determined through a replication experiment involving low-concentration samples. The general procedure, as outlined in regulatory guidance, is as follows [3]:

- Prepare Samples: Create a series of samples at low concentrations, bracketing your presumed LLOQ.

- Multiple Replicates: Analyze a minimum of five replicates per concentration level. A higher number of replicates (e.g., 24 or more) will provide a more robust estimate.

- Calculate Precision and Accuracy: For each concentration level, calculate the %CV (precision) and the relative error from the nominal value (accuracy).

- Define Acceptance Criteria: The LLOQ is the lowest concentration level at which both precision (%CV) and accuracy (relative error) meet your pre-defined acceptance criteria (e.g., ±20-25% for both parameters) [3] [2].

It is critical to note that for qPCR, the conventional approach for calculating LoB and LoD using linear measurements and blank samples is not applicable because negative samples do not produce a Cq value, preventing the calculation of a standard deviation. Therefore, the replication-based method described above is the recommended alternative [3].

Q3: My standard curve shows a correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.99, but my low-concentration quality controls are consistently inaccurate. What could be wrong?

A high R² value alone is not a sufficient indicator of a good assay. This discrepancy often points to an issue with the assay's linear range or the validity of the standard curve at the lower end.

- Potential Cause: The standard curve may appear linear by statistical measure, but the performance at the LLOQ may be inadequate. The LLOQ might have been set too low, or there could be matrix effects or inhibition affecting the low-concentration samples specifically.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Re-evaluate LLOQ: Re-perform the LLOQ validation experiment as described in Q2. Ensure that at your claimed LLOQ, both precision and accuracy meet acceptance criteria with the required number of replicates.

- Check for Inhibition: Spike a known low concentration of the target into your sample matrix and compare the recovery to the same concentration in a clean buffer. A significant drop in recovery indicates matrix interference [1].

- Verify Standard Integrity: Ensure that the standard used for the low-concentration points has been properly diluted and has not degraded.

- Inspect Amplification Plots: Manually examine the amplification curves of your low-concentration standards and QCs. Look for abnormal curve shapes or high variability in Cq values, which can indicate issues with amplification efficiency at low target levels.

Q4: How do I establish the linear range and ULOQ for my assay?

The linear range is established by running a standard curve with a minimum of five concentrations that bracket the expected range of your samples, from below the LLOQ to above the ULOQ [2].

- Prepare Standard Curve: A dilution series of the reference standard (e.g., a plasmid with the target sequence or calibrated genomic DNA) is analyzed [1] [4].

- Perform Regression Analysis: The Cq values are plotted against the logarithm of the nominal concentration. A regression analysis is performed on the data points [1].

- Assess Linearity: The linear range is the interval over which the relationship between Cq and log(concentration) is linear. This is assessed by the correlation coefficient and the visual inspection of the standard curve.

- Determine ULOQ: The ULOQ is the highest concentration standard that still falls within the linear range and for which precision and accuracy (like those at the LLOQ) meet the acceptance criteria. Concentrations above the ULOQ may show signal saturation or a significant drop in precision and accuracy.

A well-performing qPCR assay typically has a linear dynamic range spanning several orders of magnitude (e.g., 5-6 logs) with a PCR efficiency between 90% and 110%, which corresponds to a standard curve slope between -3.6 and -3.1 [1].

Q5: How can I improve the precision of my viral load measurements?

Poor precision (high %CV) can stem from multiple sources. A systematic check is required.

- Pipetting Errors: Use calibrated pipettes and ensure technicians are trained. Use master mixes to minimize pipetting steps.

- Reagent Inhomogeneity: Ensure all reagents are thoroughly mixed and aliquoted consistently.

- Inhibition: Co-purified inhibitors from the sample matrix (e.g., heme from blood, components in respiratory fluids) can cause variability. Include an internal positive control (IPC) spiked into each sample to detect inhibition [4].

- Primer/Probe Quality: Ensure primers and probes are of high quality, have high specificity, and are used at optimal concentrations. Probe-based qPCR is generally recommended over dye-based methods for superior specificity in regulated studies [1].

- Instrument Calibration: Ensure the real-time PCR instrument is properly calibrated for the fluorophores you are using.

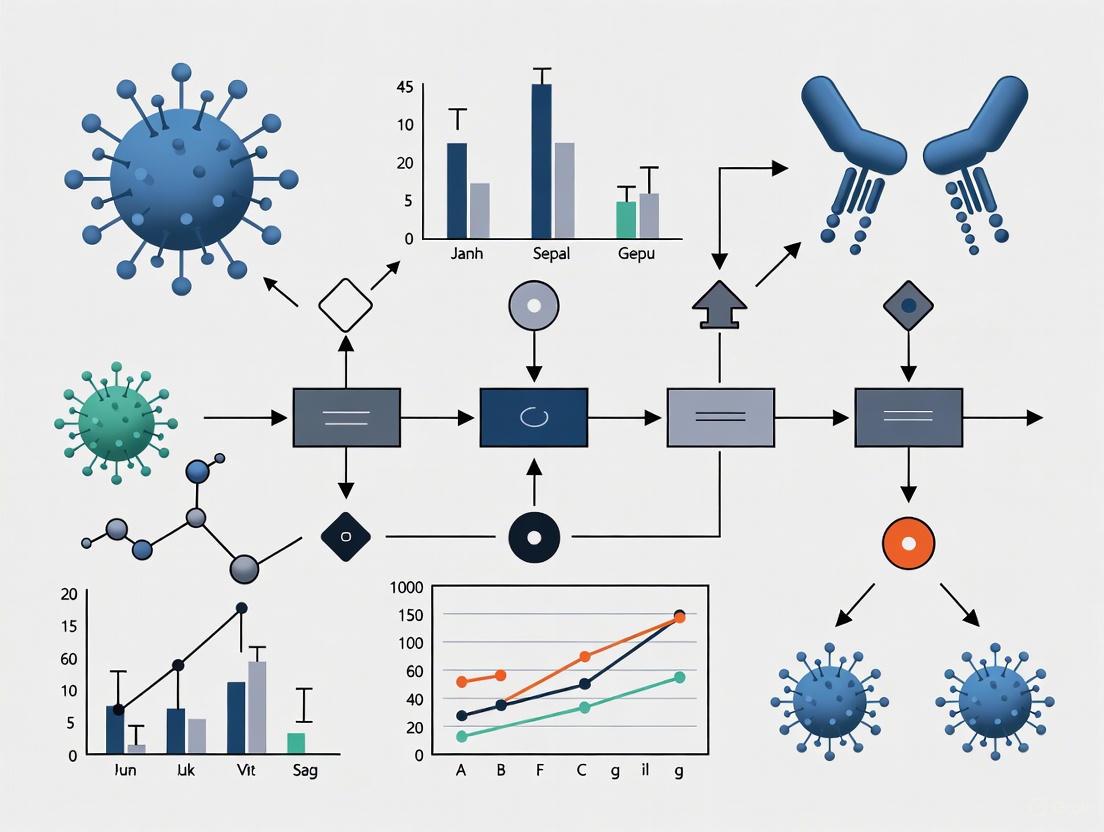

The following workflow can help you systematically diagnose and address precision issues:

The table below summarizes the core validation parameters, their experimental protocols, and typical acceptance criteria for a qPCR-based viral assay.

Table 1: Key Validation Parameters for Viral qPCR Assays

| Parameter | Experimental Protocol | Key Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Precision [2] | Analyze a minimum of five replicates of at least three concentrations (low, medium, high QC levels) within a single run (repeatability) and across different runs/days/analysts (intermediate precision). | CV ≤ 25% (at LLOQ) and ≤ 20% at other levels. Variance in inter-run precision should be comparable to intra-run variance [2]. |

| Linearity [1] [2] | Analyze a standard curve with a minimum of five concentration levels, serially diluted, covering the entire expected range. Plot Cq values vs. log10(concentration). | Correlation coefficient (R²) ≥ 0.99. PCR efficiency (E) between 90%–110% (slope of -3.6 to -3.1) [1]. Visual inspection of residuals. |

| LLOQ [3] [2] | Analyze at least five replicates of several low-concentration samples. The lowest concentration where both precision and accuracy are acceptable is the LLOQ. | Precision (CV) and accuracy (relative error) within ±20-25% [3]. The target should be detected in ≥95% of replicates (for LoD) [3]. |

| ULOQ | The highest standard in the dilution series that still falls within the linear range and meets precision/accuracy criteria. | Precision (CV) and accuracy within ±20-25%. No signal saturation or significant deviation from the standard curve's linear regression. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful validation of a viral assay relies on high-quality, well-characterized reagents. The following table lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Viral qPCR Assay Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard [1] [4] | A well-quantified material used to construct the standard curve for absolute quantification. | Plasmid DNA, in vitro transcribed RNA, or calibrated genomic DNA (e.g., NIST standard). Should be sequence-verified. |

| Primers & Probe [1] [5] | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target amplification and detection. | Probe-based (e.g., TaqMan) is recommended for superior specificity in regulated studies. Primers should be designed to avoid cross-reaction with host DNA [1]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and salts. | Includes a hot-start enzyme to prevent non-specific amplification. May contain uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) to prevent carryover contamination [5]. |

| Matrix DNA / gDNA [1] | DNA extracted from naive (untreated) host tissue. | Added to standard and QC samples to mimic the composition of actual test samples and account for potential PCR inhibition. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples [6] | Samples of known concentration used to monitor assay performance during validation and routine use. | Prepared at low, medium, and high concentrations. Can be diluted reference standard or independently prepared controls [6]. |

| Internal Positive Control (IPC) | A control target spiked into each sample to check for PCR inhibition. | Can be a non-competitive synthetic sequence or a control gene. Abnormal Cq values in the IPC indicate inhibition in the sample [4]. |

The Critical Role of Precision in Viral Load and Neutralization Assays

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

What are the key parameters to validate for a precise viral load or neutralization assay?

For both viral load and neutralization assays, rigorous validation is essential. The table below summarizes the core parameters and their performance targets, derived from established laboratory practices and recent publications [7] [8] [9].

| Validation Parameter | Typical Performance Target | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | Correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.99 [7] [9] | HIV-2 assay: 10–1,000,000 copies/mL (R² >0.99) [7] |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | Consistent detection at the lowest concentration [7] [9] | HIV-1 C subtype SYBR Green assay: 50 copies/mL [9] |

| Precision (Intra-assay) | Low standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) [7] | HIV-2 assay: Intra-run SD of 0.093 at 1.7 log₁₀ copies/mL [7] |

| Precision (Inter-assay) | Consistent results across different runs and operators [7] | HIV-2 assay: Inter-run SD of 0.162 [7] |

| Specificity | No cross-reactivity with related viruses or host material [7] [9] | HIV-2 assay: No cross-reaction with HIV-1, even at high concentrations [7] |

| Robustness | Tolerates minor variations in incubation time, reagent lots, and freeze-thaw cycles [10] | Measles pseudovirus assay: Performance stable despite variations in incubation time and freeze-thaw cycles [10] |

My neutralization assay shows high variability. What are the most common causes and solutions?

High variability often stems from inconsistencies in biological materials or protocol execution. Here are specific issues and their remedies:

- Problem: Inconsistent Cell Culture Health and Passage Number.

- Solution: Standardize cell culture conditions rigorously. Use low-passage cells and ensure consistent viability and confluence at the time of assay setup. The genetic instability of tumor-derived cell lines like HeLa can significantly impact results, so standardizing passage number and culture conditions is critical [11].

- Problem: Unoptimized Critical Reagent Concentrations.

- Solution: Systematically titrate key reagents like virus input and serum incubation time. For example, the smallpox PRNT50 assay was optimized using a virus concentration of 4 × 10² plaque-forming units/mL and a neutralization time of 60 minutes [8]. Record lot numbers for all reagents, as antibody quality can vary considerably between batches [11].

- Problem: Inaccurate Data Interpretation from Incomplete Dilution Series.

- Solution: Implement a robust statistical framework. The CoreTIA framework uses a Bayesian analysis pipeline (Hill-MCMC) to reliably estimate the ND50 (50% neutralization dose) even when dilution series are incomplete, reducing the need for repeat testing and saving sample [12].

How can I improve the efficiency of high-throughput viral load testing without sacrificing accuracy?

Pooled testing is a validated strategy to increase efficiency in populations with low positivity rates, such as routine monitoring of HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy.

- Principle: Specimens are tested in pools. If a pool is negative, all individual specimens in it are reported as negative. Only pools that test positive are reflexed to individual testing [13].

- Efficiency Gain: A study in Cameroon testing pools of three used only 6,797 assays to report results for 12,396 specimens—an efficiency of 0.55 assays per result. This enabled an 80% increase in testing capacity [13].

- Accuracy Consideration: While pooling dilutes individual samples, its impact on clinical accuracy is minimal for viral load monitoring. In the Cameroon study, the limit of detection per specimen increased from <40 copies/mL to <120 copies/mL, but an estimated only 0.01% of unsuppressed specimens (≥1,001 copies/mL) were misclassified as suppressed [13]. This demonstrates robust performance for identifying treatment failure.

My assay fails to detect the target virus or shows weak signal. What should I check?

- Confirm Primer/Probe Specificity: Assays designed for one viral subtype may underperform for others. An HIV-1 viral load assay optimized for Indian subtype C strains demonstrated superior detection of local isolates compared to two commercial kits that failed to amplify 10-13% of samples [9].

- Verify Sample Integrity: While some viral RNAs like HIV-1 are stable at ambient temperature for a limited time [9], establish strict sample handling and storage protocols to prevent degradation.

- Validate Pseudovirus Function: For neutralization assays using pseudotyped viruses, always confirm infectivity in your specific cell line. A measles pseudovirus study showed infectivity was highly dependent on the cell line used, working best in cells expressing the specific receptor SLAM [10].

Why is precise linearity validation critical for viral assays?

Precise linearity ensures that the assay provides a truthful and proportional measurement across the entire range of expected viral concentrations. This is non-negotiable for clinical and research decision-making.

- Accurate Quantification: A linear response (R² > 0.99) allows for confident interpolation of unknown sample concentrations from a standard curve [7] [9].

- Clinical Relevance: In HIV care, a 0.5 log change in viral load is considered clinically significant. Imprecise assays risk misclassifying patient status. One study found that commercial assays underestimated the viral load by >0.5 log in 4-8% of samples compared to a validated test [9].

- Reliable Serostatus Assessment: In measles serology, a robust pseudovirus neutralization assay showed that vaccination induced high geometric mean titers (GMT) that persisted in children, crucial data for informing public health vaccination policies [10].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol: Pseudotyped Virus Neutralization Assay for Measles Antibodies

This high-throughput method allows for the sensitive detection of neutralizing antibodies against multiple circulating measles virus genotypes [10].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

Cell Preparation:

- Seed an appropriate cell line (e.g., 293T-SLAM for measles) in a 96-well plate at a density determined during assay optimization [10]. Allow cells to adhere overnight.

Serum-Pseudovirus Incubation:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the test serum samples.

- Mix a fixed volume of each serum dilution with a pre-titered amount of the measles pseudotyped virus (expressing a luciferase reporter).

- Incubate the serum-virus mixtures for a standardized time (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C to allow neutralization.

Infection:

- Remove the growth medium from the prepared cells.

- Add the serum-virus mixtures to the cells. Include controls: virus-only control (0% neutralization) and cell-only control (100% neutralization/background).

Incubation and Detection:

- Incubate the plates for the determined period (e.g., 24-48 hours).

- After incubation, lyse the cells and quantify the luciferase activity using a luminometer.

Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage neutralization for each serum dilution:

(1 - (Sample Luminescence / Virus-only Control Luminescence)) * 100. - The neutralization titer (NT50) is the serum dilution that inhibits 50% of the luciferase signal. This can be calculated using a sigmoidal dose-response model [10].

- Calculate the percentage neutralization for each serum dilution:

Protocol: Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT) for Smallpox Vaccines

The PRNT is a gold-standard method for quantifying neutralizing antibodies against vaccinia virus (VACV) and assessing vaccine immunogenicity [8].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

Virus and Cell Preparation:

- Prepare a working stock of vaccinia virus (VACV) at a concentration of 4 × 10² plaque-forming units (PFU)/mL [8].

- Grow a confluent monolayer of susceptible cells (e.g., Vero cells) in a multi-well plate.

Neutralization Reaction:

- Prepare two-fold or four-fold serial dilutions of the test serum.

- Combine equal volumes of each serum dilution with the prepared virus suspension.

- Incubate the mixture at 37°C for 60 minutes to allow neutralization.

Plaque Formation:

- Remove the growth medium from the cell monolayers.

- Inoculate the serum-virus mixtures onto the cells. Include virus control wells (virus without serum).

- Adsorb the virus for a specified time (e.g., 1 hour) at 37°C, with occasional rocking.

- After adsorption, overlay the cells with a semi-solid medium (e.g., 1% carboxymethylcellulose) to prevent viral spread through the liquid medium, ensuring discrete plaque formation.

- Incubate the plates for 3 days at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [8].

Plaque Visualization and Counting:

- After incubation, remove the overlay and stain the cells with crystal violet solution. Live cells will stain, while areas of infection (plaques) will appear as clear zones.

- Count the plaques in each well.

Analysis:

- The PRNT50 is the serum dilution that reduces the number of plaques by 50% compared to the virus control wells. This can be determined by plotting the percentage plaque reduction against the serum dilution and interpolating the 50% endpoint [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Considerations for Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudotyped Viruses [10] | Safe, high-throughput surrogate for wild-type virus in neutralization assays. | Must be titrated to optimal infectious units; receptor specificity must match cell line [10]. |

| Cell Lines with Defined Receptors [10] | Platform for virus infection and neutralization. | Use low-passage, well-characterized stocks (e.g., 293T-SLAM). Cell passage number and health are major sources of variability [11]. |

| International Standard (WHO/NIBSC) [7] | Calibrator to harmonize results across labs and assays. | Essential for traceability and accuracy. The HIV-2 standard was critical for validating the novel assay [7]. |

| Internal Control (IC) RNA [7] | Monitors RNA extraction and amplification efficiency; identifies inhibition. | Should be non-competitive and added at a known concentration before extraction to control for technical variability [7]. |

| Reference Panels [9] | Validate assay performance, sensitivity, and specificity. | Composed of well-characterized samples with known status/titer; used for inter-assay precision testing [9]. |

| Critical Buffers & Additives (e.g., Poly-L-lysine) [12] | Enhance cell adhesion and consistency of monolayer formation. | Standardized coating procedures are necessary for robust and reproducible cell-based assays [12]. |

Establishing Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity for Viral Targets

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues in Viral Assay Validation

Problem: Inconsistent results across replicates

- Potential Causes: Inconsistent pipetting technique, inadequate mixing of reagents, or plate stacking during incubation leading to uneven temperature distribution [14].

- Solutions: Calibrate pipettes regularly and ensure tips are properly sealed. Mix all reagents and samples thoroughly before use. Avoid stacking plates during incubations to ensure even heat distribution [14].

Problem: Weak or no signal detection

- Potential Causes: Reagents not equilibrated to assay temperature, omission of protocol steps, or incorrectly stored/expired reagents [15].

- Solutions: Equilibrate all reagents (except enzymes) to room temperature before use. Carefully follow protocol instructions and check expiration dates of all reagents [15].

Problem: Non-linear standard curve

- Potential Causes: Pipetting errors during serial dilution, incorrect calculations, or precipitate formation in wells [15].

- Solutions: Remake standard dilutions with careful pipetting. Check calculations and fitting equations specified in the datasheet. Inspect wells for precipitates or bubbles [15].

Problem: High background noise or false positives

- Potential Causes: Inadequate washing leaving unbound antibody, contamination from cross-reacting substances, or insufficient assay specificity [14] [16].

- Solutions: Ensure complete washing steps between incubations. Validate assay specificity against closely related viral strains. Include appropriate controls to identify contamination [17] [16].

Precision Performance Across Different Assay Platforms

Table: Precision Ranges for Various Viral Detection Assays

| Assay Type | Intra-Assay CV Range | Inter-Assay CV Range | Inter-Operator CV Range | Optimal Response Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetramer Assay | 4%-15% [18] [19] | 5%-18% [19] | 5%-20% [19] | >0.25% CD8+ T cells [19] |

| Cytokine Flow Cytometry | 5%-20% [18] [19] | 10%-30% [19] | 15%-35% [19] | >0.25% CD8+ T cells [19] |

| ELISPOT | 10%-133% [18] [19] | 25%-60% [19] | 30%-60% [19] | >30 SFC/2.5×10⁵ PBMC [19] |

| Multiplex PCR | 4%-20% [17] | 10%-25% [17] | 15%-30% [17] | 10-400 copies/μL [17] |

Establishing Acceptance Criteria for Validation Parameters

Table: Recommended Acceptance Criteria for Analytical Method Validation

| Validation Parameter | Recommended Acceptance Criteria | Basis for Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Excellent: ≤5% of tolerance; Acceptable: ≤10% of tolerance [20] | Percentage of specification tolerance consumed by method error [20] |

| Repeatability | Analytical methods: ≤25% of tolerance; Bioassays: ≤50% of tolerance [20] | Control of out-of-specification (OOS) rates [20] |

| Bias/Accuracy | ≤10% of tolerance for both analytical methods and bioassays [20] | Alignment with product specification limits [20] |

| LOD | Excellent: ≤5% of tolerance; Acceptable: ≤10% of tolerance [20] | Risk-based approach relative to product specification [20] |

| LOQ | Excellent: ≤15% of tolerance; Acceptable: ≤20% of tolerance [20] | Risk-based approach relative to product specification [20] |

| Linearity | R² ≥0.85-0.99 depending on assay type [18] [19] | Demonstrated linear response across 80-120% of specification range [20] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the key differences between establishing sensitivity for molecular vs. immunological viral assays? Molecular assays (such as PCR) typically define sensitivity as the lowest copy number detected 95-100% of the time, with values ranging from 1.2-1280.8 copies/μL depending on the platform and target [21]. Immunological assays (such as ELISPOT or flow cytometry) express sensitivity relative to cell percentages, with precision highly dependent on response levels (CVs from 4% to 133%) [18] [19]. The fundamental difference lies in the units of measurement and the inherent variability of cellular systems versus nucleic acid detection.

Q: How should we determine appropriate sample sizes for validation studies? For precision studies, a minimum of 6 replicates per assay is recommended for intra-assay precision, with 8 assays performed on different days for inter-assay precision [18] [19]. For linearity studies, 7 replicates at each concentration across a dilution series provides sufficient statistical power [21]. These sample sizes allow for reliable calculation of standard deviation and coefficient of variation while accounting for normal experimental variability.

Q: What strategies can improve detection sensitivity in multiplex viral assays? Several approaches can enhance sensitivity: (1) Incorporation of target enrichment steps, such as multiplexed RT-PCR amplification prior to detection [17]; (2) Depletion of host background nucleic acids using ribosomal RNA probes [16]; (3) Optimization of hybridization conditions and signal amplification [17]; (4) Using advanced detection technologies such as electrochemical sensing or high-throughput microscopy [17] [22]. The choice depends on the specific platform and viral targets.

Q: How do we handle validation when reference standards are not available? When formal reference standards are unavailable, the recommended approach includes: (1) Creating in-house standards using characterized viral isolates or synthetic constructs [21]; (2) Using percent recovery calculations relative to theoretical concentrations [20]; (3) Establishing interim specifications based on clinical relevance until formal standards are obtained [20]; (4) Collaborating with other laboratories to harmonize approaches [14].

Q: What criteria define successful linearity in viral assay validation? Linearity success criteria include: (1) R² values ≥0.85-0.99 depending on the assay type [18] [19]; (2) No systematic pattern in residuals from regression analysis [20]; (3) No statistically significant quadratic effect in evaluation of residuals [20]; (4) Demonstration of linear response across at least 80-120% of the product specification range or intended operating range [20].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Comprehensive Assay Validation Protocol

Protocol 1: Establishing Analytical Sensitivity and Precision

This protocol provides a standardized approach for determining limit of detection (LOD) and precision parameters for viral assays.

Materials Required:

- Viral standards or isolates with known concentrations [21]

- Appropriate cell lines or matrix for dilution series [21] [19]

- Assay-specific reagents and equipment [17]

- Statistical software for data analysis

Procedure:

- Prepare Standard Dilutions: Create a dilution series spanning the expected detection range. For nucleic acid-based assays, use plasmid DNA with confirmed copy numbers [21]. For cellular assays, use PBMC from characterized donors [19].

Determine LOD: Test 7 replicates at each concentration, using both nuclease-free water and relevant biological matrix as diluents. The LOD is the lowest concentration detected 95-100% of the time [21].

Assess Precision:

Calculate Validation Parameters:

Establish Acceptance: Compare calculated parameters against predefined acceptance criteria (see Table 2) [20].

Viral Assay Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Assay Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Examples | Critical Storage Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characterized Viral Standards | Reference material for sensitivity and linearity studies | RRV, UMAV, Influenza isolates for spiking experiments [21] [16] | Temperature varies by virus; aliquot to avoid freeze-thaw cycles |

| Plasmid DNA Controls | Quantitative standards for molecular assays | pCR2.1 vectors with viral inserts for copy number determination [21] | -20°C or -80°C in nuclease-free TE buffer |

| Custom rRNA Depletion Probes | Host background reduction for metatranscriptomics | Mosquito-specific rRNA probes for arbovirus surveillance [16] | -20°C; protect from light and nucleases |

| Multiplex PCR Master Mixes | Simultaneous amplification of multiple viral targets | Influenza Panel (5 types) and Respiratory Panel (14 viruses) [17] | -20°C; multiple freeze-thaw cycles to be avoided |

| Hybridization Buffers & Signal Probes | Target detection in multiplex systems | Ferrocene-labeled probes for electrochemical detection [17] | Temperature varies by formulation; often 4°C protected from light |

| Reference Biological Matrices | Diluent for assessing matrix effects | Characterized PBMC, pooled negative sera, clarified mosquito homogenates [19] [16] | Cryopreservation at -80°C or liquid nitrogen |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring assay performance over time | Cryopreserved PBMC with low/medium/high response levels [19] | Consistent cryopreservation protocol; avoid temperature fluctuations |

Statistical Foundations for Assay Validation and Acceptance Criteria

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key statistical parameters used to define assay linearity, and what are their typical acceptance criteria?

Linearity confirms that an analytical method produces results proportional to the analyte concentration across a specified range. The evaluation involves several statistical parameters and acceptance criteria, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Statistical Parameters for Linearity Validation

| Parameter | Description | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Measures the proportion of variance in the measured concentration explained by the expected concentration. | R² > 0.995 [23] |

| Slope | The slope of the regression line (on a log scale for bioassays) indicates how measured potency changes relative to expected potency. | A slope of 1.0 indicates perfect proportionality. Confidence Intervals (CI) for the slope should be contained within a pre-defined Equivalence Acceptance Criterion (EAC) [24] [25]. |

| Intercept | The y-intercept of the regression line indicates constant bias. | An intercept of 0 indicates no constant bias. CI for the intercept should be contained within a pre-defined EAC [24] [25]. |

| Residual Plots | Visual assessment of the differences between observed and predicted values. | Residuals should be randomly scattered around zero with no discernible patterns [23]. |

FAQ 2: How do I establish acceptance criteria for assay accuracy and precision?

Accuracy (closeness to the true value) and Precision (closeness of repeated measurements) are fundamental. A modern approach involves setting criteria based on the probability of an Out-Of-Specification (OOS) result.

- Accuracy is expressed as %Relative Bias (%RB) [25].

- Precision is measured as the %Coefficient of Variation (%CV) for intermediate precision [24] [25].

- Setting Criteria: Acceptance criteria are defined for the 90% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of %RB and %CV. These CIs must fall within pre-set limits for the assay to be considered valid [24] [25].

- Total Analytical Error (TAE): The updated USP <1033> guidance suggests using TAE, which statistically combines accuracy and precision into a single acceptance criterion linked to the probability of an OOS result. This provides a more holistic check of assay validity [25].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between validating an FDA-approved test and a laboratory-developed test (LDT)?

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations mandate different levels of validation depending on the test's origin, particularly for the Reportable Range (linearity) and Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection).

Table 2: Key Validation Requirement Differences: FDA-Approved vs. Laboratory-Developed Tests

| Performance Characteristic | FDA-Approved/Cleared Test | Laboratory-Developed Test |

|---|---|---|

| Reportable Range (Linearity) | Verify using 5-7 concentrations across the stated linear range, with 2 replicates at each concentration [26]. | Establish using 7-9 concentrations across the anticipated range; 2-3 replicates at each concentration [26]. |

| Analytical Sensitivity (LoD) | Not required by CLIA, though CAP requires verification for quantitative assays [26]. | Establish with ~60 data points (e.g., 12 replicates from 5 samples) near the expected detection limit, conducted over 5 days [26]. |

| Precision | Verify per manufacturer's claims, typically testing controls over 20 days [26]. | Establish with a minimum of 3 concentrations tested in duplicate over 20 days [26]. |

| Analytical Specificity | Not required by CLIA [26]. | Must establish by testing for interference from substances like hemolysis, lipemia, and genetically similar organisms [26]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Linearity (Low R² or Non-Random Residuals)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inappropriate Concentration Range

- Solution: Ensure the calibration range brackets the expected sample concentrations. A common approach is to prepare at least five concentration standards from 50% to 150% of the target range [23].

- Cause: Matrix Effects

- Cause: Instrument Saturation or Low Signal

- Solution: Verify the analytical method's dynamic range. Detector saturation can flatten responses at high concentrations, while low signals at the range's end can increase variability [23].

Problem 2: Failing Accuracy or Precision Acceptance Criteria

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: High Imprecision (%CV)

- Cause: High Relative Bias (%RB)

- Solution: Check the calibration standards for accuracy and degradation. Evaluate potential interference from the sample matrix using a recovery study, where a known amount of analyte is spiked into the matrix and the measured value is compared to the expected value [27].

- Cause: Overly Strict Acceptance Criteria

- Solution: Use a statistical performance approach. Simulated data can show the likelihood of meeting all validation criteria for a given level of assay precision (%CV). This helps subject matter experts set realistic, statistically sound acceptance criteria [24].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol for a Linearity and Range Experiment

This protocol is adapted from established guidelines for method validation [23] [27].

1. Preparation of Standards:

- Prepare a minimum of five concentration levels over the claimed range of the assay (e.g., 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150% of the target concentration).

- Each concentration should be prepared in triplicate to assess variability.

- Standards should be prepared in the same matrix as the intended samples (e.g., blank serum, buffer) to control for matrix effects.

2. Analysis:

- Analyze all samples in a random run order to prevent systematic bias.

- Follow the established assay procedure meticulously.

3. Data Analysis:

- Plot the measured concentration (or response) against the expected concentration.

- Perform a linear regression analysis to determine the R², slope, and intercept.

- Examine the residual plot (difference between observed and predicted values vs. expected concentration). The residuals should be randomly scattered around zero.

4. Interpretation:

- The linearity is accepted if the R² meets the acceptance criterion (e.g., >0.995), and the confidence intervals for the slope and intercept fall within the pre-defined EAC. The residual plot should show no obvious patterns [24] [23].

Protocol for a Precision Experiment

This protocol follows the principles outlined in validation guides [27] [26].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Select a minimum of two concentrations (high and low) of quality control (QC) samples within the quantitative range.

- These QC samples should be aliquoted and stored appropriately to ensure stability throughout the testing period.

2. Experimental Design:

- Analyze the QC samples in duplicate or triplicate over at least 5 separate operating days.

- This design allows for the calculation of both within-run (repeatability) and between-run (intermediate precision) variation.

3. Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (%CV) for the results at each concentration.

- The total imprecision can be calculated by pooling the data from all runs.

4. Interpretation:

- The %CV for repeatability and intermediate precision is compared against pre-defined acceptance criteria. These criteria are often based on the required performance for the assay's intended use [27].

Diagram 1: Assay Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Viral Load Assay Validation

| Item | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides an analyte of known concentration and quality for calibrating assays, determining accuracy, and establishing the standard curve. | Commercial reference materials from national metrology institutes (e.g., Chinese National Institute of Metrology) were used to validate an RT-ddPCR assay [28]. |

| Inactivated Virus Stocks | Used for specificity testing and as a positive control to ensure the assay detects the intended target without cross-reacting with similar organisms. | Inactivated pathogens (e.g., Parainfluenza virus, Adenovirus) were used to assess the analytical specificity of a multiplex respiratory virus assay [28]. |

| Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify nucleic acids (DNA/RNA) from complex biological matrices (e.g., blood, swabs) for subsequent molecular detection. | The QIAamp DNA Mini Kit was used to extract orthopoxvirus DNA from non-human primate blood in a validated PCR assay [29]. |

| One-Step RT-ddPCR Master Mix | An all-in-one reagent for reverse transcription and digital PCR amplification, enabling absolute quantification of RNA viruses without a standard curve. | The One-Step RT–ddPCR Advanced Kit for Probes was used in an automated high-throughput quadruplex assay for respiratory viruses [28]. |

| Primers & Probes | Specifically designed oligonucleotides that bind to and fluorescently label the target viral gene sequence for detection and quantification. | Primers and probes targeting the matrix protein (M) gene of influenza A and RSV, and the ORF1ab of SARS-CoV-2 were synthesized for a quadruplex assay [28]. |

For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating the regulatory landscape for assay validation is crucial for the success of clinical trials and market approval. Assay validation provides the objective evidence that an analytical method is fit for its intended purpose, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of data submitted to regulatory agencies. The core principles of validation—including accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity—are universally acknowledged, yet the implementation guidelines can vary between major regulatory bodies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) [30] [31] [27].

Understanding the nuances between these guidelines is particularly critical for advanced applications, such as viral assays in vaccine development or biomarker quantification, where measuring endogenous analytes presents unique challenges that differ from traditional pharmacokinetic studies [30] [32]. This technical support center is designed to help you troubleshoot specific issues and implement validation strategies that meet global regulatory standards.

The table below summarizes the core guidelines and their primary focus from the FDA, EMA, and ICH. This overview helps in understanding the foundational documents for assay validation.

| Regulatory Body | Key Guideline(s) | Primary Focus & Scope |

|---|---|---|

| FDA | 2025 Biomarker Assay Validation Guidance [30] | Clarifies that ICH M10 for drug assays is a starting point, but biomarker assays require different approaches for endogenous analytes [30]. |

| 21 CFR Part 11 [31] | Requirements for electronic records and electronic signatures. | |

| EMA | Annex 11 (EU GMP) [31] | Detailed requirements for computerized systems validation. |

| Guideline on virus safety (EMEA/CHMP/BWP/398498/2005) [33] | Viral safety evaluation of biotechnological investigational medicinal products. | |

| ICH | ICH Q2(R1) [32] | Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology. |

| ICH Q5A(R2) [33] | Viral Safety Evaluation of Biotechnology Products. | |

| ICH E6(R3) [34] | Good Clinical Practice (effective January 2025). |

Troubleshooting Common Assay Validation Issues

FAQ: Precision and Linearity

Q: Our viral copy-number assay (ddPCR) is showing high variability (%CV) between replicate measurements. How can we improve precision and demonstrate acceptable linearity?

A: High precision is critical for assays used in potency determination, such as viral titer assays [32]. To troubleshoot precision and linearity:

- Review Your Reference Standard: For viral copy-number assays, consider using a well-qualified hybrid amplicon as a reference control. A synthetic DNA fragment containing the target amplicons (e.g., WPRE and RPP30) can be a robust and reproducible alternative to traditional plasmids or cell lines, improving both precision and accuracy [35].

- Assess the Entire Range: Systematically test the precision across the assay's entire range of quantification. The assay should be tested with "varying amount of input DNA" to establish the upper limit, lower limit, and, crucially, the linearity of the response [35].

- Statistically Evaluate Linearity: Avoid simply comparing point estimates to a pre-specified limit. Use robust statistical methods like the Two One-Sided Tests (TOST) procedure to prove linearity, as older methods may inflate type I error rates and lead to incorrect conclusions [36].

- Document Conditions: Ensure intermediate precision (e.g., between-run, between-day) is thoroughly investigated by varying factors like analyst, equipment, and day, and clearly state these conditions in your validation report [27].

FAQ: Platform Validation for Viral Clearance

Q: We are developing a new monoclonal antibody. For an early-phase clinical trial application, can we use platform validation data for viral clearance instead of product-specific validation?

A: Yes, platform validation is increasingly accepted by global regulators, but specific conditions must be met. The recent China CDE Guideline (Jan 2024), which aligns with FDA and EMA principles, states that platform validation can be used in early-phase trials if [33]:

- The process module is based on sufficient prior data (e.g., validation results from 3-5 related products with similar characteristics and processes).

- Assay methods with the same principles are used.

- Critical process parameters do not exceed the worst-case conditions of the platform.

- For virus filtration, at least one product-specific validation study using parvovirus must be conducted.

The underlying principle, echoed in ICH Q5A(R2), is a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of viral clearance for the unit operation and a comparison of the biochemical properties of the products [33].

FAQ: Biomarker Assay Validation

Q: The new 2025 FDA Biomarker Guidance references ICH M10. Does this mean our biomarker ligand-binding assays must now be validated exactly like PK assays?

A: No, this is a common misconception. The 2025 guidance states that the approach for drug assays (ICH M10) should be the starting point, but it explicitly recognizes that biomarker assays require different considerations [30]. The fundamental difference is that biomarker assays measure endogenous analytes, which makes the technical approach distinct from the spike-recovery methods used for drug concentration assays [30].

Your validation must demonstrate suitability for measuring the endogenous analyte. While you will still investigate parameters like accuracy, precision, and parallelism, the technical execution should be adapted. The European Bioanalysis Forum (EBF) emphasizes that biomarker assays benefit more from Context of Use (CoU) principles than a strict PK SOP-driven approach [30].

FAQ: Managing Validation Throughout the Product Lifecycle

Q: How do we maintain a validated state for a commercial product, and what are the key differences between FDA and EMA expectations for ongoing verification?

A: Both agencies view validation as a lifecycle activity, but their emphasis differs. The following table compares their approaches to continued process verification, a concept that also applies to analytical methods.

| Aspect | FDA (Continued Process Verification - CPV) | EMA (Ongoing Process Verification - OPV) |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Data-driven, real-time statistical process control and trend analysis [37]. | Based on real-time or retrospective data, often incorporated into Annual Product Quality Reviews [37]. |

| Documentation | Does not mandate a Validation Master Plan (VMP) but expects a structured, equivalent document [37]. | Requires a Validation Master Plan (VMP) to outline the scope, responsibilities, and timeline [37]. |

| Batch Requirements | Recommends a minimum of 3 consecutive successful batches for Process Qualification [37]. | Does not mandate a specific number; requires a scientific justification based on risk [37]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Precision Validation

This protocol is based on established methodologies for immunoassay and viral assay validation [27] [32].

1. Define Experiment Levels: - Repeatability (Intra-assay): Analyze the same sample multiple times (e.g., n=6 or more) in a single run by the same analyst. - Intermediate Precision (Inter-assay): Analyze the same sample over multiple separate runs (e.g., 3-5 days), different analysts, or different equipment.

2. Sample Preparation: Use a minimum of two quality control (QC) samples spanning the dynamic range of your assay (e.g., low, mid, and high concentrations). Use a matrix as close to the study sample as possible.

3. Execution: - For intra-assay precision, run all replicates of the QC samples in one batch. - For intermediate precision, include the QC samples in several different analytical runs.

4. Data Analysis: - Calculate the mean concentration and standard deviation (SD) for each QC level. - Determine the Coefficient of Variation (%CV) as (SD / Mean) * 100. - Compare the %CV to pre-defined acceptance criteria. For a viral plaque assay, for example, intra-assay %CVs of 6.0% to 18.7% have been demonstrated as acceptable [32].

Protocol for Robustness Testing

Robustness is the ability of a method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [27].

1. Identify Critical Parameters: List procedural steps that could reasonably vary in a routine laboratory (e.g., incubation time ±5%, temperature ±2°C, reagent concentration ±5%, different analysts).

2. Experimental Design: - Use a set of samples with known concentrations (e.g., low and high QC samples). - Perform the assay while systematically varying one parameter at a time from its nominal value. - Keep all other conditions constant.

3. Data Analysis: - Measure the impact of each variation on the assay result (e.g., reported concentration or % recovery). - If a variation causes a significant change in the result, tighten the control limits for that parameter in your final assay protocol. - The goal is to define acceptable operational ranges (e.g., "incubation time: 30 ± 3 minutes") that ensure reliable performance [27].

Visualizing the Validation Workflow and Regulatory Strategy

Assay Validation and Lifecycle Management Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in the assay validation lifecycle, from initial design to ongoing verification, integrating requirements from both FDA and EMA.

Platform Validation Strategy for Viral Clearance

This diagram outlines the decision-making process for applying a platform validation approach to viral clearance studies, as per CDE, FDA, and EMA guidelines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The table below lists essential reagents and materials critical for successful viral assay validation, as derived from the cited validation studies.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard (Hybrid Amplicon) | Serves as a qualified control for quantifying viral copy number; demonstrates accuracy, precision, and linearity. | A synthetic DNA fragment containing WPRE and RPP30 amplicons for ddPCR VCN assay validation [35]. |

| Cell Line (Vero E6) | Provides the host cell system for viral plaque assays; critical for demonstrating specificity and robustness. | Vero E6 cells from a characterized Working Cell Bank (WCB) used to validate an rVSV-SARS-CoV-2-S vaccine plaque assay [32]. |

| Semisolid Overlay Medium (e.g., Tragacanth Gum) | Restricts viral spread to form discrete, countable plaques in infectivity assays; essential for precision. | Used in the validated plaque assay for BriLife vaccine to ensure plaques were distinguishable for accurate counting [32]. |

| Critical Process Intermediates | Represents the "worst-case" conditions for platform validation of unit operations like viral clearance. | Used to demonstrate that new product parameters do not exceed the validated clearance capability of the platform [33]. |

Practical Implementation: Methodologies for Precision and Linearity Assessment

FAQs: Core Concepts in Precision Validation

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between intra-assay and inter-assay precision?

- Intra-assay precision (also called repeatability) measures the variability between replicate samples (e.g., multiple wells on a plate) processed within a single run of an assay. It assesses the inherent consistency of the assay procedure itself [38] [39].

- Inter-assay precision measures the variability between separate, independent runs of the same assay performed on different days, potentially by different analysts. This evaluates the consistency of the assay over time in a real-world laboratory setting [38] [39].

Q2: What are the typical acceptance criteria for precision in quantitative assays?

For well-controlled, traditional immunoassays like ELISAs, a coefficient of variation (CV) of less than 10% is a common benchmark for both intra-assay and inter-assay precision [38]. However, for more complex biological assays, such as cell-based or viral assays, higher CVs are often accepted. One study on single-cell immune assays reported CVs ranging from 4% to as high as 133%, with variability heavily dependent on the specific assay format and the response level being measured [18] [40]. The table below summarizes precision targets from different assay types.

Table 1: Precision Acceptance Criteria Across Assay Types

| Assay Type | Typical Intra-Assay CV | Typical Inter-Assay CV | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| ELISA [38] | <10% | <10% | Matrix effects, reagent stability, pipetting accuracy. |

| ELISPOT [18] [40] | Can exceed 60% at low response levels | Can exceed 60% at low response levels | Cell viability, operator skill, low frequency of responding cells. |

| Cytokine Flow Cytometry (CFC) [18] [40] | ~15% (at 0.25% response) | Varies by day and operator | Gating consistency, instrument performance, antibody lots. |

| PCR-based Viral Assay [29] | Defined by LLOQ and ULOQ | Evaluated via intermediate precision | Extraction efficiency, PCR inhibition, standard curve stability. |

Q3: How do I establish acceptance criteria for a new viral assay validation?

Acceptance criteria should be fit-for-purpose and based on the assay's intended use. Regulatory guidance suggests moving beyond traditional %CV and instead evaluating precision relative to the product's specification tolerance or design margin [20].

- For repeatability, it is recommended that the standard deviation of repeated measurements consumes ≤25% of the specification tolerance for an analytical method, and ≤50% for a bioassay [20].

- This approach directly links method performance to the risk of out-of-specification (OOS) results, providing a more meaningful basis for setting criteria in drug development [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

High Intra-Assay Variability

Problem: High CV between replicates within the same assay plate.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Inconsistent pipetting technique.

- Solution: Implement regular pipette calibration and user training. Use reverse pipetting for viscous liquids and ensure consistent pre-wetting of tips.

- Cause: Improper plate washing.

- Solution: For ELISA/ELISPOT, ensure thorough and consistent washing. Manually wash with a consistent stream and soak time, or validate the performance of an automated plate washer to prevent clogged needles [39].

- Cause: Edge effects on microplates.

- Solution: Use a thermosealer for plates during incubation to prevent evaporation. If incubating in a humidified chamber, ensure uniform humidity across the plate.

High Inter-Assay Variability

Problem: Results for the same control sample vary significantly between different assay runs.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Lot-to-lot reagent variability.

- Solution: Perform bridging studies when introducing new lots of critical reagents (e.g., antibodies, enzyme conjugates, peptide pools) before using them for sample analysis [39].

- Cause: Inconsistent cell preparation (for cell-based assays).

- Solution: Standardize cell isolation, counting, and cryopreservation protocols meticulously. For ELISpot, use serum-free freezing media and control freezing rates to maintain consistent PBMC viability and functionality across experiments [41].

- Cause: Drift in instrument calibration.

- Solution: Adhere to a strict preventive maintenance and calibration schedule for all critical instrumentation, including plate readers, flow cytometers, and PCR machines [29].

Failure to Meet Linearity Requirements

Problem: Dilutions of a sample do not fall along a linear curve, making accurate quantification impossible.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Matrix interference from sample components.

- Solution: Perform spike-and-recovery experiments in the sample matrix (e.g., serum, plasma). If recovery is outside the 80-120% range, modify the sample diluent or introduce a purification step [38] [39].

- Solution: For PCR-based viral assays, investigate and mitigate PCR inhibitors that may be co-extracted with the target DNA, which can cause non-linear dilution curves [29].

- Cause: Hook effect (prozone effect) in immunoassays.

- Solution: Test samples at multiple dilutions to ensure you are operating within the dynamic range of the assay and not in a region of antigen excess [39].

Experimental Protocols for Precision Validation

Protocol for Determining Intra-Assay Precision

Objective: To quantify the variability within a single assay run.

Materials:

- Quality Control (QC) samples at low, medium, and high concentrations of the analyte.

- All standard assay reagents and equipment.

Method:

- Prepare the QC samples according to your standard procedure.

- For each QC level (low, medium, high), analyze a minimum of n=6 replicates on the same microplate or within the same assay run [18] [40] [38].

- Process the entire plate using your validated assay protocol.

- For each set of replicates, calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (%CV).

- %CV = (Standard Deviation / Mean) x 100

Acceptance: The %CV for each QC level should meet pre-defined criteria (e.g., <10-15% for ELISA, though higher for cellular assays) [38].

Protocol for Determining Inter-Assay Precision

Objective: To quantify the variability of the assay across different runs over time.

Materials:

- The same batch of QC samples (low, medium, high) as used for intra-assay precision, aliquoted and stored appropriately to ensure stability.

Method:

- Over the course of a validation study, analyze the low, medium, and high QC samples in duplicate or triplicate in a minimum of 3-6 separate assay runs [38] [29].

- These runs should be performed:

- Collate the results for each QC level from all runs.

- For each QC level, calculate the overall mean, SD, and %CV across all runs.

Acceptance: The overall %CV for each QC level should meet pre-defined criteria, demonstrating the assay's robustness over time [38].

Experimental Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing and troubleshooting assay precision.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Validation of Viral and Immunoassays

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard [38] [39] | Calibrates the assay; used to generate the standard curve for quantification. | Should be traceable to a recognized standard (e.g., NIBSC). Stability and proper storage are critical. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples [38] [29] | Monitors precision and accuracy across runs. Prepared at low, mid, and high concentrations. | Must be representative of the test samples and stable for the duration of the validation. |

| Validated Antibody Pairs [42] [39] | Core component for specificity in immunoassays (ELISA, ELISPOT). | Requires titration for optimal signal-to-noise. Specificity must be tested against related analytes. |

| Peptide Pools (for T-cell assays) [18] [41] | Stimulate antigen-specific T-cells in functional assays like ELISPOT and CFC. | Purity (>80%), sequence coverage, and solubility (DMSO stock) are key. |

| Cryopreserved PBMCs [18] [41] | Provide a renewable, consistent source of responder cells for cellular immune assays. | Viability post-thaw and consistency in isolation/cryopreservation protocols are paramount. |

| PCR Master Mix & Probes [29] | Enable specific and efficient amplification of viral targets in real-time PCR assays. | Lot-to-lot consistency, resistance to inhibitors, and optimized primer/probe concentrations are vital. |

Quantifying Linear Dynamic Range in Viral Detection Assays

Why Linear Dynamic Range Matters in Viral Detection

In viral detection, the Linear Dynamic Range is the concentration range over which the assay's signal response is directly proportional to the amount of viral analyte present [43]. A broad linear range is crucial for accurately quantifying viruses across diverse clinical scenarios—from early infection with low viral loads to peak replication with high titers. Assays with a narrow range require laborious sample dilutions, increase reagent use, and risk reporting inaccurate quantitative results if samples fall outside the validated range [44] [45]. Properly validating this range ensures that results are both reliable and reproducible, forming a cornerstone of precise viral research and diagnostics.

Core Concepts and Definitions

- Linear Dynamic Range: The range of template concentrations (from the lowest to the highest) over which the assay's measurement signal (e.g., fluorescence) increases in direct proportion to the concentration of the target [43]. Outside this range, saturation occurs at high concentrations and detection fails at low concentrations.

- Linearity (R²): A statistical measure (between 0 and 1) representing how well the data points fit a straight line. Typically, R² ≥ 0.980 is considered acceptable for a qPCR standard curve, indicating a strong linear relationship [43].

- Slope: The slope of the standard curve in qPCR is used to calculate the amplification efficiency. An ideal efficiency (90–110%) corresponds to a slope of approximately -3.32 [43].

The following workflow outlines the key steps for establishing and validating the linear dynamic range of a viral detection assay:

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems & Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High signals/saturated standard curves | Standard reconstituted with incorrect (low) volume; incubation times too long [46]. | Reconstitute standard with correct volume; decrease plate, detection antibody, or substrate incubation times [46]. |

| Sample readings outside range | Analyte concentration is below detection limit or higher than the highest standard point [46]. | Concentrate low-titer samples or dilute high-titer samples; re-analyze [46]. |

| Assay fails unexpectedly after reagent batch change | Different PCR assays show individual sensitivity to minute changes in reaction mixture components, even from the same manufacturer [47]. | Validate new reagent batches with all critical assays; purchase large reagent batches for consistency; have alternative manufacturer protocols ready [47]. |

| Reduced digital PCR (dPCR) efficiency | Sample impurities (salts, alcohols, proteins) or complex template structures (supercoiled plasmids, large DNA) [48]. | Use high-purity nucleic acid kits; for complex structures, employ restriction digestion (ensure enzyme does not cut within amplicon) [48]. |

| Narrow dynamic range in LC-MS/MS | Detector saturation at high analyte concentrations [44] [45]. | Utilize multiple product ions or natural isotopologue transitions to create parallel calibration curves for high and low sensitivity ranges [44] [45]. |

Experimental Protocols for Determining Linear Dynamic Range

Protocol 1: Establishing Linear Dynamic Range for qPCR/qRT-PCR

This protocol is foundational for validating quantitative PCR assays used in viral load monitoring [43] [49].

Preparation of Standard Curve:

Assay Run and Data Collection:

- Amplify the dilution series using the optimized qPCR conditions.

- Record the Ct (threshold cycle) value for each replicate.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the log of the starting template concentration against the mean Ct value for each dilution.

- Perform linear regression analysis on the plot. The assay is considered linear where this relationship forms a straight line.

- Acceptance Criteria: The curve should demonstrate a coefficient of determination (R²) of ≥ 0.990 (or ≥ 0.980, depending on stringency), and the calculated amplification efficiency should be between 90% and 110% [43] [49].

Protocol 2: Expanding Dynamic Range in LC-MS/MS Assays

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) can suffer from detector saturation. This protocol uses a multi-ion strategy to extend the upper limit of quantification [44].

Ion Selection:

Calibration and Validation:

- Establish two separate calibration curves using the two different ions.

- Validate both curves independently, ensuring each meets pre-defined precision (e.g., CV within 20%) and accuracy criteria [44].

- The overall reportable range of the assay becomes the combination of the two curves, effectively expanding the total dynamic range by one or more orders of magnitude [44] [45].

Advanced Applications & Techniques

Digital PCR (dPCR) for Absolute Quantification

dPCR partitions a sample into thousands of individual reactions, allowing for absolute quantification without a standard curve. It is less susceptible to PCR inhibitors and offers high precision for quantifying low-abundance targets [50]. Key considerations for dynamic range in dPCR include:

- Partition Number: The dynamic range is fundamentally limited by the number of partitions. Platforms generating 10 million droplets can achieve a wide dynamic range of up to 6 logs [50].

- Sample Input: To maximize sensitivity for ultra-low targets, the platform must accommodate large nucleic acid inputs (e.g., micrograms of DNA) without inhibition [50].

Expanding Range with Single-Molecule Counting

Innovative imaging techniques are pushing the limits of fluorescence assays. By combining single-molecule counting for low concentrations with calibrated ensemble intensity measurements for high concentrations, researchers can expand the dynamic range to nearly 1,000,000-fold down to femtomolar levels [51]. This is particularly promising for detecting rare cancer biomarkers like circulating miRNAs.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

| Item | Function in Validation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Armored RNA / Quantified Standards | Provides stable, non-infectious standards for creating serial dilutions to generate the standard curve [49]. | Armored RNA Quant SARS-CoV-2 panel [49]. |

| One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix | A ready-to-use mix containing all core components for reverse transcription and PCR, reducing setup errors and variability [47]. | Batch-to-batch consistency is critical; validate new lots extensively [47]. |

| Hydrolysis Probes (TaqMan) | Provide sequence-specific detection in qPCR and dPCR, crucial for specific viral target quantification [48]. | Use at higher concentrations in dPCR (e.g., 0.25 µM) for better fluorescence [48]. |

| Nucleic Acid Purification Kits | Ensure high-purity template free of contaminants (salts, alcohols, proteins) that can inhibit amplification and skew results [48]. | Essential for reliable dPCR and qPCR performance [48]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled (SIL) Peptides | Internal standards for LC-MS/MS assays that account for sample loss during preparation and allow precise quantification [52]. | Used in SISCAPA (Stable Isotope Standards and Capture by Anti-Peptide Antibodies) workflows [52]. |

This technical support center is designed as a resource for researchers and scientists engaged in the development and validation of microneutralization (MN) assays for yellow fever (YF) vaccines. Framed within a broader thesis on viral assay precision and linearity validation, the content below addresses specific, high-priority experimental challenges in the form of detailed troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs). The information synthesizes current standards and data to support robust assay performance for the detection and quantification of YF virus-neutralizing antibodies, a critical component for vaccine licensure.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Assay Performance Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Microneutralization Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High intra-assay variability | Inconsistent cell seeding density or viability. | Standardize cell culture protocols; ensure Vero cells are healthy and used at a consistent passage number. Count cells before seeding to ensure uniform density across wells. |

| Poor precision (high %CV) | Inaccurate serial dilution of serum samples; pipetting errors. | Use calibrated pipettes and perform dilutions meticulously. For critical studies, use an automated liquid handler to improve reproducibility [53]. |

| Loss of signal or high background in immunostaining | Improper antibody dilution; incomplete cell fixation or permeabilization. | Titrate all antibodies to determine optimal concentration. Ensure fixation (e.g., with 10% formaldehyde) and permeabilization (e.g., with Triton X-100) steps are performed for the correct duration [54]. |

| Inconsistent neutralization titers between runs | Variation in virus stock titer (TCID₅₀) used between experiments. | Aliquot and titrate virus stocks to determine the exact TCID₅₀ for each batch. Use a consistent, pre-qualified virus dose in every assay run [55] [56]. |

| Failure to meet linearity or accuracy criteria | Serum matrix interference (e.g., from hemolytic, lipemic, or icteric samples). | Validate assay performance using various serum matrices during development. The YF MN assay has demonstrated suitable specificity across such interfering substances [53]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol 1: Assessing Intra-Assay and Intermediate Precision

- Objective: To determine the repeatability (intra-assay precision) and intermediate precision of the microneutralization assay.

- Methodology:

- Prepare a minimum of three replicates of at least two internal quality control (IQC) samples (e.g., a high-titer and a low-titer positive control) within the same assay run to assess intra-assay precision [53].

- Repeat this process across three separate assay runs, performed by different analysts on different days, to assess intermediate precision.

- Calculate the geometric mean titer (GMT) and the percentage geometric coefficient of variation (%GCV) for the results from both the intra-assay and intermediate precision experiments.

- Acceptance Criterion: A validated YF MN assay demonstrated suitable intra-assay precision with a %GCV of 36% and intermediate precision with a %GCV of 54% [53].

Protocol 2: Determining Assay Linearity and Dilutional Accuracy

- Objective: To confirm that serum samples can be accurately diluted without affecting the measured neutralizing antibody titer.

- Methodology:

- Select a high-titer positive human serum sample.

- Perform a series of linear dilutions (e.g., two-fold or three-fold) in negative human serum to maintain a consistent matrix.

- Test each dilution in the MN assay and calculate the observed titer.

- Plot the observed titers against the expected titers and perform linear regression analysis.

- Acceptance Criterion: The assay should demonstrate a linear relationship with an R² value of >0.98 [57]. The back-calculated concentrations for each dilution should fall within predefined limits (e.g., ±2-fold) of the expected value [53].

Protocol 3: Establishing the Lower and Upper Limits of Quantification (LLOQ & ULOQ)

- Objective: To define the range of antibody titers that can be reliably quantified.

- Methodology:

- Prepare serial dilutions of a positive control serum near the expected lower and upper limits of detection.

- Run these samples in multiple replicates (e.g., N=≥24) across several independent assays.

- The LLOQ is the lowest titer where both precision (%GCV) and accuracy (relative to the expected value) meet pre-specified criteria. For the YF MN assay, an LLOQ of 10 (1/dil) was validated with a %GCV of 38% for repeatability [53].

- The ULOQ is the highest titer that can be accurately measured without a prozone effect or signal saturation. The validated YF MN assay reported a ULOQ of 10,240 (1/dil) [53].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using a microneutralization assay over the traditional plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) for yellow fever vaccine studies?

A1: The MN assay offers several key advantages for high-throughput clinical testing needed for vaccine licensure:

- Higher Throughput: It is performed in a 96-well microtiter plate format, allowing for the simultaneous testing of dozens of samples compared to the more cumbersome 24- or 6-well plate format of the PRNT [53] [56].

- Reduced Labor and Time: The MN assay with an immunostaining readout does not require a solid overlay and can be completed faster than the PRNT, which relies on plaque formation. Furthermore, imaging and analysis can be automated [58] [56].

- Smaller Sample Volume: The assay requires less serum, which is particularly beneficial for pre-clinical studies or pediatric trials where sample volumes are limited [56].

- Objective Readout: While PRNTs can involve subjective plaque counting, the MN assay can use immunostaining and automated imaging for a more quantitative and objective readout of infection foci [58].

Q2: How is the specificity of the yellow fever MN assay confirmed, especially given cross-reactivity concerns with other flaviviruses?

A2: Assay specificity is confirmed by testing sera against other orthoflaviviruses. During the validation of the YF MN assay, its specificity was demonstrated using samples containing antibodies against related viruses such as dengue virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and Zika virus. The assay successfully distinguished YF-specific neutralizing antibodies, showing minimal cross-reactivity [53].

Q3: What are the critical reagents and their quality controls in a validated YF MN assay?

A3: The reliability of the assay depends on several critical reagents:

- Virus Stock: A well-characterized YF-17D virus stock with a predetermined titer (TCID₅₀/mL). Consistency in the virus working dose is paramount [53].

- Cell Line: Vero cells, which must be maintained under consistent culture conditions and monitored for mycoplasma contamination and passage number [53] [54].

- Internal Quality Controls (IQCs): A panel of controls, including high-titer and low-titer anti-YF positive controls and a negative control. Their valid titer ranges must be established, with over 90% of results falling within a pre-defined ±2-fold range of the geometric mean titer [53].

- Detection Antibodies: For immunostaining, specific primary and conjugated secondary antibodies (e.g., HRP-conjugated) must be titrated for optimal performance [54].

Q4: What short-term stability conditions have been validated for serum samples in this assay?

A4: Validation studies have shown that YF virus-neutralizing antibodies in human serum remain stable under specific short-term conditions. Antibody titers were demonstrated to be stable in serum samples after undergoing up to five freeze-thaw cycles or when stored at 2°C to 8°C for up to 14 days. In these studies, results remained within the two-fold assay variability limit [53].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for YF Microneutralization Assay

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Vero Cells (ATCC CCL-81) | Host cell line for virus infection and replication. | Monitor for contamination and maintain consistent passage number; check for mycoplasma [53] [54]. |

| YF-17D Virus | Antigen used to challenge serum antibodies in the neutralization. | Use a consistent, pre-titered stock. Aliquots should be stored at ≤-60°C to maintain infectivity [53]. |

| Internal Quality Controls (IQCs) | Monitor precision and accuracy within and across assay runs. | Include high-positive, low-positive, and negative controls. Establish a valid range for positive IQCs (e.g., GMT ±2-fold) [53]. |

| Anti-Yellow Fever Virus Antibodies | Detection of infected cells (for immunostaining readout). | Target viral proteins like the envelope or non-structural proteins. Requires titration to optimize signal-to-noise ratio [53]. |

| Cell Culture Medium (e.g., cDMEM) | Supports cell viability and growth during the assay. | Typically supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics [55] [54]. |

| Fixation Solution (e.g., 10% Formaldehyde) | Preserves cells and inactivates virus after the incubation period. | Essential step before immunostaining; must be performed in a biosafety cabinet [54]. |

| Permeabilization Agent (e.g., Triton X-100) | Allows detection antibodies to enter cells and bind intracellular viral proteins. | Concentration and incubation time must be optimized to avoid destroying cell morphology [54]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

YF MN Assay Workflow

Assay Validation & Quality Control Logic