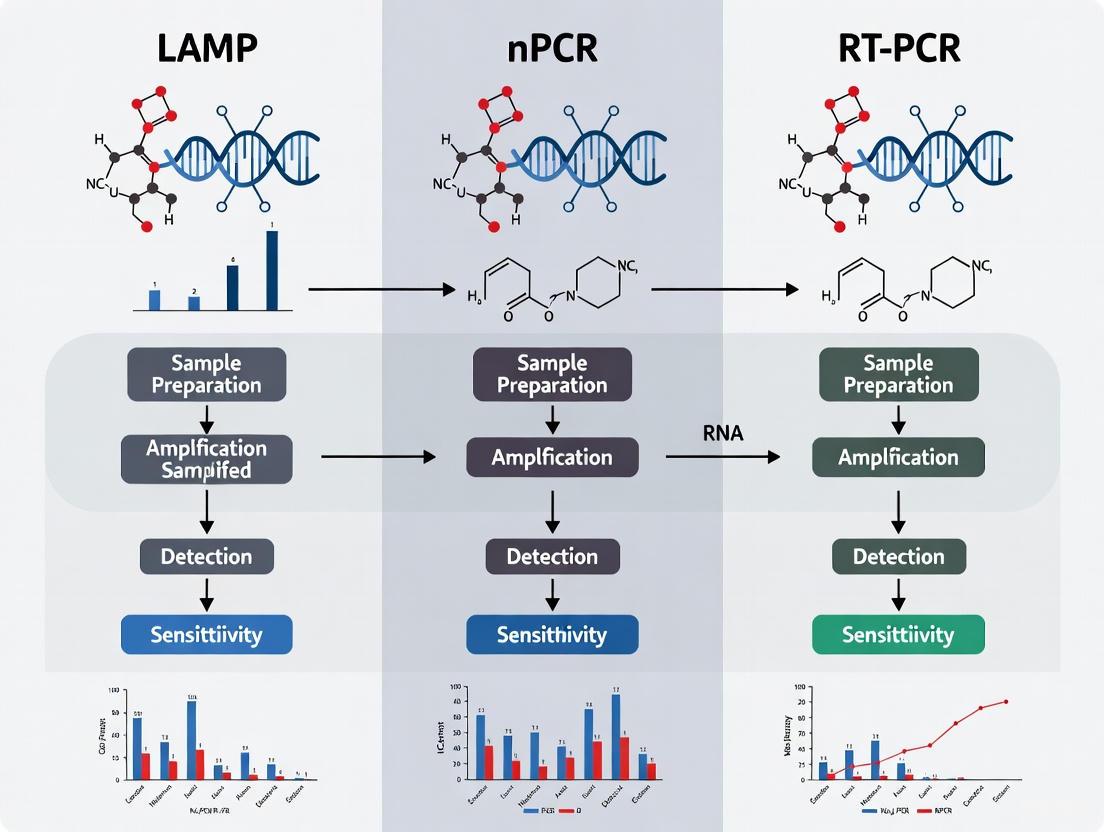

LAMP vs nPCR vs RT-PCR: A Comprehensive Sensitivity Comparison for Molecular Diagnostics

This article provides a systematic comparison of the sensitivity, specificity, and practical application of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), nested PCR (nPCR), and real-time PCR (RT-PCR) for researchers and drug development...

LAMP vs nPCR vs RT-PCR: A Comprehensive Sensitivity Comparison for Molecular Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of the sensitivity, specificity, and practical application of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), nested PCR (nPCR), and real-time PCR (RT-PCR) for researchers and drug development professionals. Drawing from recent clinical and analytical studies, we explore the foundational principles of each technique, their methodological workflows in detecting pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, Entamoeba histolytica, and carbapenem-resistant bacteria, and direct head-to-head sensitivity comparisons. The content also covers crucial troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance assay performance, and validates findings with clinical data. This resource aims to guide the selection of the most appropriate molecular diagnostic tool for specific research and clinical settings, balancing sensitivity, speed, cost, and operational complexity.

Understanding the Core Technologies: Principles of LAMP, nPCR, and RT-PCR

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) represents a significant advancement in nucleic acid amplification technology, offering a rapid, sensitive, and specific alternative to traditional PCR-based methods. Since its introduction in 2000, LAMP has been incorporated into diagnostic assay development for numerous medically important communicable diseases including Salmonella Typhimurium, pathogenic Leptospira, and toxigenic Vibrio cholerae [1]. This innovative technique has revolutionized molecular biology research and clinical diagnostics by enabling DNA amplification under isothermal conditions, thereby eliminating the need for sophisticated thermal cyclers [2] [1]. The technique employs a DNA polymerase with high strand-displacement activity and utilizes 4-6 primers recognizing 6-8 distinct regions of the target DNA, resulting in highly specific amplification [2] [3]. The exceptional sensitivity, specificity, speed, accuracy, and affordability of LAMP have made it particularly valuable for point-of-care diagnostics and field applications where resources may be limited [4] [3].

Compared to conventional PCR, nested PCR (nPCR), and real-time PCR (qPCR), LAMP demonstrates several distinct advantages in amplification efficiency. A comparative analysis study revealed that LAMP outperformed these PCR methods in terms of limit of detection (LoD) and amplification time [5] [1]. While LAMP detected a single Entamoeba histolytica trophozoite, both qPCR and nPCR recorded LoD of 100 trophozoites, and conventional PCR demonstrated an LoD of 1000 trophozoites [1]. This enhanced sensitivity, coupled with its rapid reaction time and operational simplicity, positions LAMP as a relevant alternative DNA-based amplification platform for sensitive and specific detection of pathogens [5].

Fundamental Principles of LAMP

Core Mechanism and Reaction Dynamics

The fundamental mechanism of LAMP centers on its isothermal amplification process, which occurs at a constant temperature range of 60-65°C, typically around 65°C [3]. This contrasts sharply with conventional PCR that requires thermal cycling between different temperatures. The reaction is initiated by a DNA polymerase with high strand-displacement activity such as Bst-XT WarmStart DNA Polymerase [3]. This enzyme begins synthesis and enables the specially designed primers to form "loop" structures that facilitate subsequent rounds of amplification through extension on the loops and additional annealing of primers.

A key characteristic of the LAMP reaction is the production of very long DNA products (>20 kb) formed from numerous repeats of the short (80–250 bp) target sequence, connected with single-stranded loop regions in long concatemers [2] [3]. These complex structures contain multiple opportunities for initiating synthesis, and the strand displacing Bst DNA Polymerase uses these priming points, resulting in rapid exponential amplification [2]. The amplification efficacy of LAMP beyond exponential has significantly shortened amplification duration compared to PCR-based methods, with reactions often completing within 15-60 minutes depending on optimization [4] [1].

Primer Design Strategy

The exceptional specificity of LAMP stems from its sophisticated primer design strategy that requires recognition of 6-8 distinct regions within the target DNA. A complete LAMP primer set consists of:

- F3 and B3 (Outer Primers): These are the forward and backward outer primers that help initiate the strand displacement process. Their Tm is typically about 59-61°C [2].

- FIP and BIP (Inner Primers): These forward and backward inner primers contain two distinct sequences complementary to the target DNA, which are responsible for forming the loop structures. Their Tm is typically about 64-66°C [2].

- LF and LB (Loop Primers): These optional but recommended loop primers accelerate the reaction by binding to the loop regions formed during amplification, providing additional initiation sites for DNA synthesis [3].

The distance between primer regions follows specific constraints: the distance between 5' end of F2 and B2 is typically 120-160 bp, while the distance between F2 and F3 as well as B2 and B3 is 0-20bp. The distance for loop-forming regions (5' of F2 to 3' of F1, 5' of B2 to 3' of B1) is 0-40bp [2]. This precise arrangement enables the formation of the characteristic "dumbbell" structure that contains multiple opportunities for initiating synthesis, resulting in rapid exponential amplification [2].

Table 1: LAMP Primer Components and Their Functions

| Primer Name | Type | Recognition Regions | Function | Typical Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F3 and B3 | Outer Primers | 2 regions | Initiate strand displacement | 59-61°C |

| FIP and BIP | Inner Primers | 4 regions | Form loop structures for auto-cycling | 64-66°C |

| LF and LB | Loop Primers | 2 regions | Accelerate reaction by binding loop regions | ~65°C |

Visualizing the LAMP Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of LAMP, showing the primer binding sites and the formation of loop structures that enable exponential amplification:

Diagram 1: LAMP primer binding regions and amplification mechanism. Primers recognize 6-8 distinct regions on the target DNA, forming loop structures that enable exponential amplification under isothermal conditions, producing long concatemeric DNA products.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

Comprehensive studies have demonstrated LAMP's superior sensitivity compared to various PCR methods. In a direct comparison using Entamoeba histolytica DNA derived from faecal samples, LAMP showed significantly better limit of detection (LoD) than conventional PCR, nested PCR, and real-time PCR [5] [1]. The research employed three different post-LAMP analysis methods including agarose gel electrophoresis, nucleic acid lateral flow immunoassay, and calcein-manganese dye techniques, all of which recorded identical LoD of a single E. histolytica trophozoite [1]. This exceptional sensitivity substantially outperformed all PCR methods tested in the same study.

Table 2: Comparison of Detection Limits Between LAMP and PCR Methods

| Method | Limit of Detection | Amplification Time | Equipment Needs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP | 1 trophozoite | 15-60 minutes | Heating block/water bath | [1] |

| Real-time PCR (qPCR) | 100 trophozoites | 60-120 minutes | Thermal cycler with detection system | [1] |

| Nested PCR (nPCR) | 100 trophozoites | 3-4 hours | Thermal cycler | [1] |

| Conventional PCR | 1000 trophozoites | 60-120 minutes | Thermal cycler | [1] |

The high sensitivity of LAMP has been consistently demonstrated across various applications. In plant pathology, a LAMP assay developed for detecting sunflower downy mildew (Plasmopara halstedii) achieved a detection limit of 0.5 pg/μl of pathogen DNA, surpassing the reported lowest detection limit of 3 pg for PCR-based methods [4]. Similarly, in SARS-CoV-2 detection, an optimized RT-LAMP assay demonstrated a limit of detectable template reaching 10 copies of the N gene per 25 μL reaction at isothermal 58℃ within 40 minutes [6]. Another study reported a limit of detection of 6.7 copies/reaction for SARS-CoV-2 RT-LAMP [7].

Speed and Time Efficiency

The amplification efficiency of LAMP significantly reduces reaction times compared to PCR-based methods. While conventional PCR and qPCR typically require 60-120 minutes for amplification alone (excluding analysis time), LAMP reactions are often completed within 15-60 minutes under optimal conditions [4] [1]. This time efficiency is particularly valuable in clinical and field settings where rapid results are critical for decision-making.

In SARS-CoV-2 detection, studies have demonstrated that RT-LAMP can generate results within approximately 1 hour [8]. The rapid turnaround time is attributed to the exponential amplification kinetics of LAMP, which does not require time-consuming thermal cycling. Furthermore, the elimination of post-amplification analysis steps through colorimetric or turbidity-based detection methods can provide results even faster, in some cases within 30-40 minutes [6] [7].

Specificity and Reliability

LAMP demonstrates exceptional specificity due to its requirement for multiple primers recognizing 6-8 distinct regions of the target DNA. This multi-recognition approach significantly reduces the likelihood of non-specific amplification. In one study evaluating LAMP for Entamoeba histolytica detection, the primer set recorded 100% specificity when tested against 3 medically important Entamoeba species and 75 other pathogenic microorganisms [1]. This high specificity is maintained across various applications, from clinical diagnostics to plant pathogen detection [4] [8].

The reliability of LAMP has been validated in numerous clinical studies. For COVID-19 diagnosis, RT-LAMP showed 95.45% accuracy in detecting the p.L858R variant in non-small cell lung cancer patients compared to real-time PCR and next-generation sequencing (NGS) [8]. For SARS-CoV-2 detection, one study reported that up to the 9th day after symptom onset, RT-LAMP had a positivity of 92.8%, with sensitivity and specificity compared with RT-qPCR of 100% [7]. However, the same study noted that after the 10th day after onset, the positivity of RT-LAMP decreased to less than 25%, indicating that diagnostic accuracy may vary depending on the disease stage and viral load [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard LAMP Reaction Setup

A typical LAMP reaction includes several key components that must be carefully optimized for maximum efficiency. Based on multiple studies, the standard reaction components include:

- Bst DNA Polymerase: 6-12 U (typically 8 U) of strand-displacing DNA polymerase such as Bst 2.0 Warm Start DNA Polymerase [4]

- Primers: F3/B3 (0.1-0.4 μM), FIP/BIP (0.8-3.2 μM), LF/LB (0.2-0.8 μM) [4]

- dNTPs: 1.0-1.6 mM [4]

- Mg²⁺: 6-12 mM (typically 8 mM) [4]

- Reaction Buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM (NH₄)₂SO₄, 2 mM MgSO₄, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 8.8 at 25°C [4]

- Betaine: Often added to improve reaction efficiency and specificity

- Template DNA: Typically 50 ng or less, depending on application [4]

The reaction is usually performed in a final volume of 25 μL, incubated at a constant temperature of 60-65°C for 15-60 minutes, followed by enzyme inactivation at 80°C for 5 minutes [4].

Optimization Strategies

Successful LAMP implementation requires careful optimization of several reaction parameters. Key optimization areas include:

- Temperature Optimization: Testing temperatures between 60-67°C to determine the optimal amplification temperature for specific primer-template combinations [4]

- Time Course Evaluation: Assessing amplification at different time points (15, 35, 45, 60 minutes) to determine the minimum required amplification time [4]

- Magnesium Concentration: Titrating Mg²⁺ concentrations between 6-12 mM to optimize amplification efficiency [4]

- Primer Ratio Optimization: Balancing inner and outer primer concentrations to maximize amplification yield while minimizing non-specific products [4]

The systematic optimization process typically involves varying one parameter at a time while keeping others constant, then validating the optimized conditions using target and non-target samples to confirm specificity [4].

Detection Methods

LAMP products can be detected through multiple methods, providing flexibility for different laboratory settings and applications:

- Agarose Gel Electrophoresis: Traditional method visualizing the characteristic ladder-like pattern of LAMP amplicons [1]

- Colorimetric Detection: Using dyes such as Neutral Red, Hydroxynaphthol Blue, SYBR Safe, or Thiazole Green that change color in response to amplification [4] [3]

- Turbidity Measurement: Detecting magnesium pyrophosphate precipitate formation as a white precipitate or measuring turbidity changes [3]

- Lateral Flow Dipsticks: Using immunochromatographic strips for rapid visual detection of labeled amplicons [1]

- Real-time Monitoring: Employing intercalating dyes in real-time thermal cyclers to monitor amplification kinetics [4]

The choice of detection method depends on the required sensitivity, available equipment, and intended application, with colorimetric and lateral flow methods being particularly suitable for point-of-care testing.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for LAMP Assay Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA Polymerase, Bst-XT WarmStart | Strand-displacing activity for isothermal amplification | Test concentrations 6-12 U/reaction; warm-start versions prevent non-specific initiation |

| Primer Sets | F3/B3, FIP/BIP, LF/LB | Recognize 6-8 distinct target regions for specific amplification | F3/B3: 0.1-0.4 μM; FIP/BIP: 0.8-3.2 μM; LF/LB: 0.2-0.8 μM |

| Detection Dyes | Calcein-manganese, Hydroxynaphthol Blue, SYBR Safe, Neutral Red | Visual detection of amplification through color change | Calcein-manganese: pre- and post-amplestion color change; Hydroxynaphthol Blue: blue to violet |

| Buffer Components | Betaine, MgSO₄, dNTPs, Tween-20 | Enhance reaction efficiency and specificity | Betaine reduces secondary structure; optimize Mg²⁺ at 6-12 mM; dNTPs at 1.0-1.6 mM |

| Sample Preparation Kits | Plant/Fungi DNA Isolation Kits, Viral RNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid purification for various sample types | LAMP is robust and tolerant of inhibitors, allowing for crude sample prep |

Applications and Case Studies

Clinical Diagnostics

LAMP has demonstrated significant utility in clinical diagnostics across various diseases. In COVID-19 detection, multiple studies have validated RT-LAMP as a reliable alternative to RT-qPCR, particularly during the acute phase of infection. One study found that until the 9th day after symptom onset, RT-LAMP had the same diagnostic accuracy as RT-qPCR, suggesting its utility as a diagnostic tool in the acute symptomatic phase of COVID-19 [7]. Another study reported 95.45% accuracy of a LAMP test in detecting the p.L858R somatic variant in non-small cell lung cancer patients compared to real-time PCR and NGS [8].

For parasitic infections, LAMP has shown remarkable sensitivity in detecting Entamoeba histolytica from faecal samples, with studies demonstrating detection of a single trophozoite, outperforming all PCR-based methods [1]. The 100% specificity recorded when tested against multiple related species and other microorganisms further supports its clinical utility [1].

Plant Pathology and Agricultural Applications

In agricultural diagnostics, LAMP has proven valuable for detecting plant pathogens with high sensitivity and specificity. The development of a LAMP assay for sunflower downy mildew (Plasmopara halstedii) demonstrated a detection limit of 0.5 pg/μl of pathogen DNA, surpassing conventional PCR methods [4]. The assay provided a cost-effective, field-suitable, and easily analyzable solution with high analytical sensitivity and specificity, making it ideal for use in resource-limited settings [4].

The technique has been successfully applied to detect various other plant pathogens, including barley yellow dwarf virus in cereals, Candidatus phytoplasma vitis, tomato chlorosis virus, and potato ring rot pathogen Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus [4]. The robustness of LAMP and its tolerance to inhibitors reduces the need for extensive DNA purification, further enhancing its suitability for field applications.

Field Deployment and Point-of-Care Testing

The operational characteristics of LAMP make it particularly suitable for field deployment and point-of-care testing scenarios. Its isothermal nature eliminates the need for expensive thermal cyclers, with reactions possible using simple equipment such as water baths or heat blocks [4] [3]. The rapid turnaround time (often under 60 minutes) and multiple detection options, including visual color changes, enable use in settings with limited laboratory infrastructure [3] [7].

Modeling studies evaluating testing strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic identified LAMP as a balanced option between accuracy and practicality. While RT-PCR remained the most accurate diagnostic test, RT-LAMP provided a viable alternative, particularly in resource-limited settings or where rapid screening was prioritized [9] [10]. The combination of reasonable sensitivity, speed, and minimal equipment requirements positions LAMP as a valuable tool for epidemic control and outbreak investigation.

LAMP technology represents a significant advancement in nucleic acid amplification, offering a combination of sensitivity, specificity, speed, and operational simplicity that distinguishes it from traditional PCR-based methods. The fundamental mechanism relying on isothermal amplification with multiple primers recognizing 6-8 distinct regions of the target DNA provides the foundation for its exceptional performance characteristics. Extensive comparative studies have consistently demonstrated that LAMP outperforms conventional PCR, nested PCR, and real-time PCR in terms of detection limit and amplification time while maintaining high specificity.

The versatility of LAMP is evidenced by its successful application across diverse fields including clinical diagnostics, plant pathology, oncology, and infectious disease surveillance. Its robustness, tolerance to inhibitors, and compatibility with various detection methods—from sophisticated real-time instruments to simple colorimetric changes visible to the naked eye—make it particularly valuable for point-of-care testing and resource-limited settings. As molecular diagnostics continue to evolve, LAMP stands as a powerful technique that combines analytical performance with practical implementation, offering researchers and clinicians a reliable alternative to PCR-based methods for a wide range of applications.

Nested PCR (nPCR) is a powerful modification of the conventional polymerase chain reaction that significantly enhances the sensitivity and specificity of nucleic acid detection. This technique employs two successive rounds of amplification with two distinct sets of primers to enable precise detection of low-abundance targets that might otherwise evade standard PCR methods. The fundamental principle involves an initial amplification using outer primers that target a larger DNA fragment, followed by a secondary amplification using inner primers that bind within the first amplification product. This "nested" approach provides a dual verification system that dramatically reduces non-specific amplification while increasing the reliability of results, particularly when working with challenging samples or minimal target material.

Within the molecular diagnostics landscape, nPCR occupies a crucial position between conventional PCR and more recent advancements like real-time PCR and isothermal amplification methods. While newer techniques offer advantages in quantification speed and simplicity, nPCR remains uniquely valuable for applications demanding maximum sensitivity where target DNA is scarce or sample quality is compromised. The technique's robust performance across diverse fields—from clinical pathogen detection to environmental monitoring and forensic analysis—demonstrates its enduring relevance in the researcher's toolkit, particularly when uncompromising detection certainty is required.

Performance Comparison: nPCR Versus Alternative Amplification Methods

Sensitivity and Specificity Profiles Across Platforms

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques for Pathogen Detection

| Method | Target | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Detection Limit | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nPCR | Listeria monocytogenes [11] | 100 | 100 | 3.5 UFC/25 g, 30 copies/reaction | Enhanced sensitivity/specificity, reduced inhibition sensitivity [11] | Contamination risk, longer process |

| SFTS Virus [12] | 100 | 100 | Up to 40 days post-symptom | Detects targets in convalescent phase | ||

| Schistosoma mansoni [13] | 90.06 (snails) | 85.51 (snails) | N/A | Effective for complex samples | ||

| Real-time PCR (qPCR) | Listeria monocytogenes [11] | Equivalent to nPCR | Equivalent to nPCR | 3.5 UFC/25 g, 30 copies/reaction | Faster, quantitative, lower contamination risk | Higher equipment cost |

| SFTS Virus [12] | 94.4 | 100 | Up to 21 days post-symptom | Rapid, quantitative results | Lower detection in convalescent phase | |

| Schistosoma mansoni [13] | 89.79 (overall) | 87.70 (overall) | N/A | Quantification, high throughput | ||

| LAMP | Schistosoma mansoni [13] | Highest among NAATs | Moderate | N/A | Simple, isothermal, rapid | |

| SARS-CoV-2 [14] | 84.13 | 100 | 15 copies/reaction | Equipment simplicity, rapid (≤60 min) [14] [15] | Lower sensitivity vs rRT-PCR [14] | |

| Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae [16] | >95 | >95 | N/A | Visual detection, simple operation |

Analytical Detection Limits and Time-to-Result Comparison

Table 2: Analytical Performance and Operational Characteristics

| Method | Detection Limit | Time to Result | Equipment Requirements | Quantitative Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nPCR | As low as 30 copies/reaction [11] | 3-6 hours (including gel electrophoresis) | Standard thermal cycler, gel documentation | Qualitative/Semi-quantitative |

| Real-time PCR | As low as 15 copies/reaction [14] | 1-2 hours | Real-time thermal cycler, specialized optics | Fully quantitative |

| LAMP | 100-180 copies/μL [15] | 30-60 minutes [14] [15] | Water bath/heat block, possibly spectrophotometer | Semi-quantitative |

The comparative data reveals nPCR's particular strength in achieving maximum sensitivity and specificity, often reaching 100% for both parameters as demonstrated in detection of Listeria monocytogenes and SFTS virus [11] [12]. This exceptional performance comes at the cost of longer processing time and increased contamination risk due to the need for reaction tube transfer between amplification rounds. Real-time PCR provides an excellent balance of speed and sensitivity with the added advantage of quantification capabilities, while LAMP offers the simplest operational requirements with moderately compromised sensitivity, particularly evident in the SARS-CoV-2 study showing 84.13% sensitivity compared to RT-PCR [14].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Data

nPCR Protocol for Detection ofListeria monocytogenesin Food Samples

This established protocol from the comparative study of nPCR and real-time PCR for detection of Listeria monocytogenes in soft cheese demonstrates the rigorous methodology required for reliable nPCR results [11]:

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Artificially contaminate 25g cheese samples with 3.5 to 3,500 CFU/25g of Listeria monocytogenes

- Enrich samples in half-Fraser broth at 30°C for 24h, then transfer to Fraser broth for additional 24h incubation

- Extract DNA using boiling method with PBST (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20)

- Boil 1mL of culture at 100°C for 12 minutes, centrifuge at 12,000 × g, and use supernatant as PCR template

Primer Design:

- Target: HlyA gene (listeriolysin O) of Listeria monocytogenes

- External primers: HlyA-EF (forward: 5'-CCTGCATATATCTCAAGTGTG-3') and HlyA-ER (reverse: 5'-GGCAAATAGATGGACGATGTG-3') generating 545bp product

- Internal primers: HlyA-IF (forward: 5'-CCGCAAAAGATGAAGTTCAA-3') and HlyA-IR (reverse: 5'-CCCAAGAGATGTTGAATTGAG-3') generating 255bp product

First Round PCR (50μL reaction):

- 10μL DNA template

- 100μM dNTPs, 1.5mM MgCl₂, 1.25U Taq DNA polymerase

- 0.5μM each outer primer (HlyA-EF and HlyA-ER)

- Thermal cycling: 94°C for 5min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 1min, 60°C for 1min, 72°C for 1min; final extension 72°C for 10min

Second Round PCR (25μL reaction):

- 2μL of first-round PCR product as template

- 0.5μM each inner primer (HlyA-IF and HlyA-IR)

- Remaining components identical to first round

- Thermal cycling: Identical to first round

Internal Amplification Control (IAC):

- Synthetic 85bp DNA sequence with terminal regions complementary to HlyA-FI and HlyA-RI primers

- Yields 106bp product when amplified with HlyA-FI and HlyA-RI primers

- Cloned into pGEM-T easy vector to create pGEMT-IAC plasmids

- Included in reactions to identify PCR inhibition and validate negative results [11]

nPCR Protocol for Detection of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome (SFTS) Virus

This protocol demonstrates nPCR adaptation for viral RNA detection with exceptional sensitivity, maintaining detection capability up to 40 days post-symptom onset [12]:

Target and Primer Design:

- Target: M-segment of SFTS virus genome

- Primer design follows nested principle with external and internal primer sets

- First round amplifies larger fragment, second round targets internal region

Sample Processing and Reverse Transcription:

- Collect blood samples in EDTA tubes

- Extract viral RNA using commercial extraction kits

- Perform reverse transcription using random hexamers or gene-specific primers

Two-Stage Amplification:

- First round: Conventional RT-PCR with external primers

- Second round: Nested PCR using diluted first-round product with internal primers

- Include appropriate negative and positive controls in each run

Detection and Analysis:

- Analyze second-round products by agarose gel electrophoresis

- Confirm positive results by sequencing of amplified products

- Validation against seroconversion and virus isolation confirms clinical accuracy [12]

nPCR Workflow and Technical Considerations

nPCR Workflow Diagram

The nPCR workflow involves sequential amplification steps that collectively enhance specificity and sensitivity. The process begins with sample DNA extraction using methods ranging from simple boiling to commercial kits, depending on sample complexity and purity requirements. The first amplification round employs outer primers that flank the target region, generating an initial amplification product that includes the specific target amid potential non-specific amplification. A critical product dilution step follows, transferring a small aliquot of the first reaction to minimize carryover of primers and byproducts. The second amplification round uses inner primers that bind within the first amplicon, selectively amplifying only the correct target sequence while dramatically reducing background noise. Finally, analysis by gel electrophoresis confirms the presence of the specific-sized amplicon, with the nested approach providing verification that the detected product originates from the intended target.

Critical Technical Considerations for Optimizing nPCR

Primer Design Optimization:

- Inner primers must be completely contained within the outer primer amplicon

- Avoid complementarity within and between primer sets to prevent primer-dimer formation

- Maintain similar melting temperatures within each primer pair (±2°C)

- Verify specificity through in silico analysis against relevant databases

Contamination Prevention Strategies:

- Physical separation of pre- and post-amplification work areas

- Use of dedicated equipment and supplies for each amplification stage

- Incorporation of negative controls at both amplification stages

- Implementation of UV irradiation and chemical decontamination protocols

- Consideration of closed-tube systems when possible to minimize aerosol risk

Reaction Optimization Parameters:

- Magnesium concentration titration (typically 1.5-2.5mM)

- Annealing temperature optimization for both primer sets

- Cycle number determination to balance sensitivity and specificity

- Template dilution testing to identify optimal concentration for second round

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for nPCR

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes DNA synthesis | Thermostable (e.g., Taq polymerase); must retain activity through multiple heating cycles |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for DNA synthesis | High-purity, neutral pH; typical working concentration 200μM each dNTP |

| Primer Pairs (Outer & Inner) | Target sequence recognition | HPLC-purified; designed with appropriate melting temperatures; minimal self-complementarity |

| Buffer System | Optimal enzyme activity | Typically supplied with enzyme; contains salts, sometimes with enhancers like DMSO or BSA |

| Magnesium Chloride | Cofactor for polymerase | Separate optimization required; typical range 1.5-2.5mM final concentration |

| Template DNA | Target for amplification | Quality and quantity critical; may require purification from inhibitors |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Reaction preparation | Free of nucleases that could degrade primers or templates |

| Agarose | Gel electrophoresis | High-quality, molecular biology grade for product visualization |

| Nucleic Acid Stain | DNA detection | Ethidium bromide, SYBR Safe, or equivalent for visualizing amplified products |

| Internal Amplification Control (IAC) | Inhibition detection | Non-target sequence amplified by same primers; identifies false negatives [11] |

nPCR remains an indispensable technique in the molecular biologist's arsenal when maximum detection sensitivity and specificity are paramount. The two-stage amplification process, while more time-consuming than single-round methods, provides unparalleled verification of target detection through its nested primer design. This approach demonstrates particular value in detecting low-abundance pathogens, working with compromised samples, and applications requiring absolute certainty in results.

The comparative data presented reveals that nPCR consistently achieves exceptional sensitivity and specificity profiles, often matching or exceeding alternative amplification platforms while requiring less sophisticated instrumentation. While real-time PCR offers advantages in quantification speed and reduced contamination risk, and LAMP provides extreme operational simplicity, nPCR maintains its niche for the most challenging detection scenarios. The technique's proven performance across diverse fields—from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring—ensures its continued relevance despite the emergence of newer amplification technologies. For researchers and drug development professionals requiring uncompromising detection certainty, nPCR provides a robust, reliable solution validated through decades of laboratory implementation.

This guide details the principles of Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR), a cornerstone technology in molecular diagnostics, and objectively compares its performance against two other nucleic acid amplification techniques: Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP) and nested PCR (nPCR).

Core Principles of Real-Time Fluorescence RT-PCR

Real-Time RT-PCR is a highly sensitive technique used to detect and quantify specific RNA sequences. Its core principle involves the reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by the simultaneous amplification and detection of the cDNA in real time.

The process relies on fluorescent reporter molecules. As the target sequence amplifies, the fluorescence increases proportionally. The cycle threshold (Ct) value is a critical quantitative parameter, representing the amplification cycle at which the fluorescent signal crosses a predetermined threshold. A lower Ct value indicates a higher starting concentration of the target RNA [17] [18].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow and detection mechanism.

Performance Comparison: RT-PCR vs. RT-LAMP vs. nPCR

The following tables summarize the direct experimental comparisons and key characteristics of these three techniques.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Comparison from Clinical Studies

| Methodology | Target Pathogen | Reported Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Performance Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | SARS-CoV-2 | Gold Standard [19] [14] | Gold Standard [19] [14] | Used as reference in multiple studies. |

| RT-LAMP | SARS-CoV-2 | 71% (direct swab) to 100% (extracted RNA) [19] [20] | 100% [14] [20] [21] | Sensitivity highly dependent on sample prep; optimal time ~45 min [19]. |

| RT-LAMP | SARS-CoV-2 | 84.1% (overall) [14] | 100% [14] | Sensitivity rises to 98-100% for samples with Ct < 30 [14] [21]. |

| nested PCR | Feline Calicivirus | 31.48% [22] | Not Specified | Higher detection rate vs. conventional PCR (1.85%) in clinical samples [22]. |

Table 2: Characteristic and Workflow Comparison

| Feature | RT-PCR | RT-LAMP | nPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Fluorescence-based amplification with thermal cycling | Isothermal amplification with strand-displacing polymerase | Two rounds of PCR with two primer sets |

| Amplification Temp. | Multiple (Denaturation, Annealing, Extension) [20] | Constant (~60-65°C) [19] [14] | Multiple (Two separate thermal cycling runs) [22] |

| Time to Result | 1 - 2+ hours [19] [20] | ~30 - 60 minutes [19] [14] [21] | Several hours (due to two rounds) [22] |

| Throughput | High (96/384-well formats) | Moderate to High | Low to Moderate |

| Key Advantage | Gold standard sensitivity, robust quantification | Speed, simplicity, potential for point-of-care | High specificity, sensitivity for complex samples |

| Key Limitation | Requires expensive thermal cyclers, skilled personnel [19] | Lower sensitivity with direct samples, primer design complexity [19] | High contamination risk, more complex workflow [22] |

| Quantification | Excellent (Absolute/Robust Relative) [17] | Semi-Quantitative | Qualitative / Semi-Quantitative |

Experimental Protocols and Modeling Data

Detailed RT-LAMP Protocol for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

A typical protocol for detecting SARS-CoV-2, as used in recent studies, is outlined below [14] [21].

- Primer Design: A set of six primers (F3, B3, FIP, BIP, LF, LB) is designed to recognize eight distinct regions of a target gene, such as the ORF8 or ORF1a gene of SARS-CoV-2, ensuring high specificity [19] [14].

- Reaction Setup:

- Amplification: Incubate the reaction at a constant temperature of 63°C for 45-60 minutes in a real-time PCR analyzer or a dry bath [19] [14] [21].

- Result Detection:

- Real-time: Monitor fluorescence (FAM channel) for amplification curves [14].

- Colorimetric: Visually inspect for a color change post-amplification (e.g., from orange to pink with neutral red) [21] [22].

- Post-amplification analysis: Perform melting curve analysis to verify amplification specificity [14].

Detailed nPCR Protocol for Pathogen Detection

A protocol for detecting Feline Calicivirus (FCV) exemplifies the nPCR workflow [22].

- First Round PCR:

- Use an outer primer set to perform a standard PCR reaction, amplifying a larger target region.

- Typical cycling conditions: initial denaturation (e.g., 95°C for 5 min), followed by 30-35 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension.

- Second Round (Nested) PCR:

- Use a second set of primers ("nested primers") that bind inside the amplicon generated in the first PCR.

- A small aliquot (e.g., 1-2 µL) of the first PCR product is used as the template for this second reaction.

- Run a second PCR with similar cycling conditions, but for fewer cycles (e.g., 20-25).

- Detection: Analyze the final PCR product using agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the presence and size of the amplified fragment [22].

Modeling of Testing Strategy Effectiveness

A 2025 modeling study evaluated the effectiveness of different testing strategies for COVID-19 control, considering not just test sensitivity but also turnaround time and frequency [23]. The key findings relevant to this comparison include:

- Daily screening with RT-PCR or RT-LAMP was most effective at reducing transmission risk but incurred the highest costs.

- Symptom-based testing was a more cost-effective alternative. In this context, the turnaround time was found to be a more critical factor for outbreak containment than the raw analytical sensitivity of the assay.

- Antigen tests (with lower sensitivity) were a viable, cost-effective option for symptom-based testing in resource-limited settings, underscoring that the "best" test depends on the public health goal [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Amplification Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Bst DNA/RNA Polymerase | Key enzyme for RT-LAMP; performs reverse transcription and strand-displacement DNA amplification isothermally. | New England Biolabs' WarmStart Bst [14] [20] |

| Fluorescent Probe/Dye | Enables real-time detection of amplification in RT-PCR (hydrolysis probes) or RT-LAMP (intercalating dyes). | FAM-channel dyes [14], SYBR Green [22] |

| Colorimetric Indicator | Allows visual, equipment-free detection of LAMP amplification through pH change or metal ion complexation. | Neutral red [22], phenol red [19] |

| Primer Sets (LAMP) | A set of 4-6 primers recognizing 6-8 target regions, fundamental to LAMP's specificity and efficiency. | Primers targeting SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 or ORF1a [19] [14] |

| Nested Primer Sets | Two pairs of primers for nPCR; the second "nested" set increases specificity and sensitivity by re-amplifying an internal fragment. | Primers for FCV ORF2 gene [22] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies and isolates high-quality RNA from clinical samples (e.g., swabs, saliva), critical for assay sensitivity. | Magnetic bead-based kits (e.g., MagMax) [17] [24] |

Workflow Comparison and Strategic Selection

The following diagram synthesizes the core workflows of the three techniques, highlighting their procedural differences and key characteristics.

The choice between RT-PCR, RT-LAMP, and nPCR is not a matter of one being universally superior but depends on the specific requirements of the testing scenario.

- RT-PCR remains the gold standard for applications demanding the highest sensitivity and precise quantification, such as clinical diagnostics and viral load monitoring, where resources and technical expertise are available [19] [17].

- RT-LAMP is a powerful alternative for rapid screening, field deployment, and resource-limited settings. Its speed, simplicity, and minimal equipment requirements make it ideal for point-of-care testing, though its performance can vary with sample preparation methods [19] [14] [23].

- nPCR is a highly specific technique useful for detecting low-abundance targets or in complex samples where maximum specificity is needed, despite its longer workflow and high contamination risk [22].

Ultimately, the strategic selection of a molecular diagnostic tool involves a careful balance between the need for sensitivity, speed, cost, ease of use, and the available laboratory infrastructure.

Comparative Analysis of Reaction Conditions and Enzyme Requirements

The evolution of nucleic acid amplification techniques has fundamentally transformed molecular diagnostics and research. Among these methods, Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), nested PCR (nPCR), and Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) represent significant technological milestones, each with distinct reaction conditions and enzyme requirements that directly influence their application scope and performance characteristics. This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of these fundamental parameters, drawing upon experimental data and clinical validation studies to offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals a clear framework for methodological selection. Understanding the enzymatic dependencies and optimal reaction environments for LAMP, nPCR, and RT-PCR is crucial for designing robust diagnostic assays, particularly in contexts requiring high sensitivity, rapid results, or resource-limited implementation. The following sections will dissect the core components, performance metrics, and practical protocols that define these established amplification platforms.

Fundamental Principles and Core Components

The core distinction between these techniques lies in their amplification mechanics and enzymatic requirements. LAMP is an isothermal amplification method that utilizes a strand-displacing DNA polymerase to synthesize DNA at a constant temperature, typically between 60°C and 65°C [25] [19]. This process employs four to six primers that recognize six to eight distinct regions on the target DNA, creating loop structures that enable self-priming and exponential amplification [25] [26]. In contrast, nPCR and RT-PCR are both thermocycling-based methods that rely on a thermostable DNA polymerase, such as Taq polymerase, which functions through repeated cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension at varying temperatures [5] [25].

RT-PCR specifically incorporates a reverse transcriptase enzyme to convert RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) before the amplification process, making it indispensable for RNA virus detection and gene expression analysis [25]. nPCR enhances sensitivity and specificity by performing two consecutive rounds of amplification using two sets of primers, where the product of the first PCR reaction serves as the template for the second round with primers that bind internally to the first amplicon [5] [27].

The following table summarizes the essential reagents and their functions common to these molecular techniques:

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Amplification

| Reagent | Function | LAMP | nPCR | RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Strand-displacing enzyme for isothermal amplification | Required | Not Used | Not Used |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme for thermocycling | Not Used | Required | Required |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Converts RNA to cDNA | Required (for RT-LAMP) | Not Used | Required |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for new DNA strands | Required | Required | Required |

| Primers | Bind specific target sequences for amplification | 4-6 primers | 2 sets of 2 primers | 2 primers |

| Buffer System | Maintains optimal pH and reaction conditions | Isothermal buffer | PCR buffer | PCR buffer |

Comparative Performance Data Analysis

Quantitative comparisons across multiple studies consistently reveal distinct performance profiles for each technique. A foundational study comparing LAMP, nPCR, and real-time PCR (qPCR) for detecting Entamoeba histolytica demonstrated striking differences in sensitivity. LAMP achieved a limit of detection (LoD) of a single trophozoite, outperforming both nPCR and qPCR, which recorded LoDs of 100 trophozoites each. Conventional PCR was significantly less sensitive, with an LoD of 1000 trophozoites [5]. This superior sensitivity of LAMP has been consistently documented in plant pathogen detection as well, where it showed a 10-fold improvement over conventional PCR, though it was 100-fold less sensitive than nPCR and 1000-fold less sensitive than qPCR for the specific detection of Alternaria solani [27].

In the context of SARS-CoV-2 detection, the comparative performance is more nuanced. RT-LAMP exhibited a high correlation with RT-qPCR when using extracted RNA, with some studies reporting complete agreement between the two methods [28] [19]. However, this sensitivity can decrease when using direct swab samples without RNA extraction, where RT-LAMP sensitivity relative to RT-qPCR dropped to 71% in one study [19]. The detection limit for SARS-CoV-2 RT-LAMP has been reported at 23.4-42.8 RNA copies for purified RNA, while fewer than 250 copies could not be detected using crude RNA without purification [28].

The following table synthesizes quantitative performance data from empirical studies:

Table 2: Comparative Performance Metrics of Amplification Techniques

| Technique | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Amplification Time | Reaction Temperature | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP | 1 parasite (E. histolytica) [5]; 23.4-42.8 RNA copies (SARS-CoV-2, purified RNA) [28] | 45-60 min [5] [19] | 60-65°C (constant) [25] [19] | Point-of-care testing, field diagnostics [28] [29] |

| nPCR | 100 parasites (E. histolytica) [5]; 100 fg genomic DNA (A. solani) [27] | 2-3 hours (including two rounds) [5] | 95°C, 50-65°C, 72°C (cycling) | High-sensitivity detection, pathogen differentiation [5] [27] |

| RT-PCR | 100 parasites (E. histolytica) [5]; Varies with protocol | 1.5-3 hours [26] | 95°C, 50-60°C, 72°C (cycling) | Gold standard for RNA virus detection, gene expression analysis [30] [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

RT-LAMP Assay Protocol

The RT-LAMP protocol for SARS-CoV-2 detection, as optimized by Gholami et al., utilizes a primer set targeting the ORF1a gene [19]. The reaction is typically performed in a 25 μL volume containing 12.5 μL of 2× WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP master mix (includes Bst DNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase), 1.6 μM each of FIP and BIP primers, 0.2 μM each of F3 and B3 primers, and 5 μL of extracted RNA template. The mixture is incubated at 65°C for 45 minutes in a thermal cycler or dry block heater, followed by enzyme inactivation at 80°C for 5 minutes. Results can be determined via real-time fluorescence monitoring, agarose gel electrophoresis, or visual color change when using colorimetric master mixes containing pH-sensitive dyes [19] [29]. For dengue virus detection, a similar TURN-RT-LAMP assay employs two primer sets targeting both the 5′- and 3′-UTR regions in a single reaction to enhance sensitivity, achieving >96% in clinical validation [29].

nPCR Assay Protocol

The nPCR protocol for Entamoeba histolytica detection, as described by Foo et al., involves two consecutive amplification rounds [5]. The first round uses external primers in a 25 μL reaction containing standard PCR components: 1× PCR buffer, 1.5-2.0 mM MgCl₂, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.2 μM each primer, 1.25 U Taq DNA polymerase, and 2 μL DNA template. The thermal cycling conditions are: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 58°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 1 min; with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. For the second round, 1 μL of the first PCR product is transferred to a fresh tube containing the same reaction components but with internal primers that bind within the first amplicon. The cycling conditions are identical. Products from both rounds are analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis [5].

RT-qPCR Assay Protocol

The RT-qPCR protocol for SARS-CoV-2 using the CDC (USA) protocol involves a one-step reaction where reverse transcription and PCR amplification occur in the same tube [30]. A typical 20 μL reaction contains 5 μL of extracted RNA, 10 μL of 2× reaction buffer, 0.4 μL of reverse transcriptase/Taq polymerase mix, 400-500 nM of each primer (targeting N1 and N2 genes), and 125-150 nM of probes. The thermal cycling conditions on a real-time PCR instrument are: reverse transcription at 50°C for 20 min; initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; followed by 40-45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. Fluorescence is measured at the end of each cycle, and samples are considered positive if amplification of both N1 and N2 gene fragments occurs at a cycle threshold (Ct) ≤37 [30].

Technical Workflow and Performance Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental workflows and performance relationships between these amplification techniques.

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of LAMP, nPCR, and RT-PCR

Diagram 2: Performance Attribute Comparison

This comparative analysis elucidates the distinct reaction conditions and enzyme requirements that define LAMP, nPCR, and RT-PCR methodologies. LAMP offers significant advantages in speed, operational simplicity, and cost-effectiveness, requiring only basic equipment while maintaining high sensitivity, making it ideally suited for point-of-care and resource-limited settings [28] [29]. nPCR provides exceptional specificity and sensitivity through its two-stage amplification process, though it demands more time and laboratory infrastructure [5] [27]. RT-PCR remains the gold standard for RNA target quantification with robust performance and widespread validation, albeit with higher equipment requirements and operational complexity [30] [19].

The selection of an appropriate amplification technique ultimately depends on the specific research or diagnostic context, including target type (DNA vs. RNA), required sensitivity and specificity, available resources, and intended application setting. Future advancements in primer design, enzyme engineering, and detection methodologies will continue to refine the performance and accessibility of these foundational molecular tools, further expanding their utility across biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and public health initiatives.

Key Applications and Historical Development of Each Technique

Molecular diagnostics represent a cornerstone of modern biomedical research and clinical practice, with techniques like reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), and digital PCR (dPCR) enabling sensitive detection and quantification of nucleic acids. The ongoing pursuit of greater sensitivity, specificity, and operational efficiency drives continuous innovation in this field. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three key technologies—RT-PCR, LAMP, and dPCR—focusing on their historical development, key applications, and relative performance characteristics, particularly their analytical sensitivity. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the technical capabilities and limitations of each method is crucial for selecting the optimal platform for specific diagnostic and research applications, from routine pathogen detection to absolute quantification of rare genetic targets.

Historical Development

The Evolution of PCR and RT-PCR

The invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by Kary Mullis in 1983 marked a revolutionary advancement in molecular biology [31]. The original process was tedious, requiring fresh polymerase enzyme to be added after each denaturation cycle because the initial enzyme was destroyed by high temperatures [31]. A critical breakthrough came with the utilization of a thermostable DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus (Taq polymerase), which could withstand the repeated high-temperature cycles, enabling automation and broader adoption [31]. Early thermal cyclers included both space-domain systems, where samples were moved between different temperature zones, and time-domain systems, where the sample block changed temperature; the latter became more common [31].

The application spectrum of PCR expanded rapidly from its initial use in detecting mutations for sickle cell anemia [31]. The development of multiplex PCR, which allows simultaneous amplification of multiple targets in a single tube, was another significant milestone, first used for detecting deletions in the DMD gene [31]. The integration of reverse transcription (RT) as a preliminary step enabled the amplification and study of RNA targets, giving rise to RT-PCR [32]. The subsequent development of real-time or quantitative PCR (qPCR) in 1993 allowed researchers to monitor amplification kinetics in real-time, transforming PCR from a qualitative to a fully quantitative tool [31]. RT-PCR, particularly in its quantitative form (qRT-PCR), has since become the gold standard for RNA detection and quantification, displacing older techniques like Northern blot [32].

The Emergence of Isothermal Amplification and LAMP

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) was developed by Notomi et al. in 2000 as a novel nucleic acid amplification method that operates at a constant temperature, eliminating the need for thermal cycling [33] [34]. This technique relies on a strand-displacing DNA polymerase and a set of four to six primers that recognize six to eight distinct regions on the target gene, leading to highly specific amplification [33]. The method produces up to 10^9 copies of the target in less than an hour and results can be monitored through turbidity, fluorescence, or colorimetric changes [33]. The isothermal nature of LAMP, typically between 60°C and 65°C, removes the requirement for expensive thermal cyclers, making it particularly suitable for point-of-care testing and resource-limited settings [35] [33]. Continuous improvements in polymerase enzymes, such as the development of Bst 2.0 and Bst 3.0 with enhanced speed, stability, and reverse transcriptase activity, have further advanced LAMP technology [33].

The Advent of Digital PCR

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a third-generation PCR technology that enables absolute quantification of nucleic acids without the need for standard curves [31] [17]. The core principle involves partitioning a PCR reaction into thousands of individual subsamples, such that each contains either zero or one (or a few) target molecules [31] [17]. After end-point PCR amplification, the number of positive partitions is counted, and using Poisson statistics, the absolute copy number of the target in the original sample is calculated [17]. dPCR platforms are primarily of two types: droplet-based digital PCR (ddPCR), which uses water-in-oil emulsions to create tens of thousands of nanoliter-sized reactions [31], and chip-based digital PCR (cdPCR), which uses microfabricated wells on a silicon chip [31]. This partitioning process makes dPCR exceptionally robust to PCR inhibitors and allows for precise quantification, especially of rare alleles and low-abundance targets [17].

Table 1: Historical Milestones of Molecular Amplification Techniques

| Year | Technique | Key Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | PCR | Invention by Kary Mullis [31] | Enabled targeted DNA amplification |

| 1985 | PCR | First automated system ("Baby Blue") [31] | Reduced manual intervention |

| 1987 | RT-PCR | First used for infectious disease diagnosis [31] | Expanded application to RNA targets |

| 1990s | PCR | Use of Taq polymerase [31] | Enabled full automation of thermal cycling |

| 1993 | qPCR | Real-time kinetic monitoring [31] | Transformed PCR into a quantitative tool |

| 2000 | LAMP | Description by Notomi et al. [33] | Introduced rapid, isothermal amplification |

| 2000s | dPCR | Concept of digital quantification [31] | Enabled absolute quantification without standard curves |

Technique Comparison and Performance Data

Principles and Workflows

The fundamental principles and workflows of RT-PCR, LAMP, and dPCR differ significantly, influencing their application and performance.

RT-PCR/qPCR: This method relies on the reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by thermal cycling for amplification. The quantification occurs in real-time using fluorescent chemistries. Two main approaches exist: one-step RT-PCR, where reverse transcription and PCR occur in the same tube, minimizing handling and contamination risk; and two-step RT-PCR, where the reactions are performed separately, offering more flexibility but increased handling [32]. Detection relies on fluorescent signals, with common chemistries including DNA-binding dyes (e.g., SYBR Green) and sequence-specific probes (e.g., TaqMan, molecular beacons) that provide higher specificity [32].

LAMP: This is an isothermal amplification that uses 4-6 primers targeting 6-8 regions of the desired gene. The process involves inner primers (FIP, BIP) and outer primers (F3, B3), which generate complex structures with loop regions that serve as initiation sites for subsequent amplification cycles, leading to the production of long DNA concatemers [33]. The reaction is typically performed at 60-65°C for 15-60 minutes. Results can be monitored in real-time via turbidimetry (measuring magnesium pyrophosphate precipitate), fluorometry (using DNA-intercalating dyes), or colorimetry (using pH-sensitive dyes or metal ion indicators like calcein or hydroxy naphthol blue) for visual, equipment-free detection [33] [36].

dPCR: The workflow begins with a standard PCR mixture, which is partitioned into thousands of nanoscale reactions. Each partition acts as an individual PCR microreactor. After end-point thermal cycling, the partitions are analyzed to determine the fraction that is positive for fluorescence. The absolute concentration of the target molecule is then calculated using Poisson statistics, based on the principle that the number of target molecules per partition follows a Poisson distribution [17]. This method does not require a standard curve and is less affected by inhibitors or amplification efficiency variations [17].

Sensitivity and Performance Comparison

Sensitivity is a critical parameter for comparing molecular diagnostics. Recent studies provide direct comparative data.

A 2025 study on respiratory virus diagnostics during the 2023-2024 "tripledemic" directly compared dPCR and real-time RT-PCR [17]. The results demonstrated that dPCR offered superior accuracy and precision, particularly for samples with high viral loads (Ct ≤ 25) of Influenza A, Influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads (Ct 25.1-30) of RSV [17]. dPCR showed greater consistency in quantifying intermediate viral levels, highlighting its robustness for precise quantification [17]. However, the authors noted that the routine implementation of dPCR is currently limited by higher costs and reduced automation compared to RT-PCR [17].

For LAMP, a 2025 multi-platform detection system for Human Adenovirus (HAdV) reported a limit of detection (LOD) of 2.5 copies/reaction for colorimetric (calcein) and immunochromatographic (IC) methods, while the fluorescent probe-based LAMP method demonstrated a superior sensitivity of 1 copy/reaction [36]. This fluorescent LAMP assay showed 100% concordance with qPCR when validated on 188 clinical samples (κ = 1.00) and performed reliably in low-viral-load and co-infection cases, with a rapid detection time of ≤20 minutes [36].

Another modeling study on COVID-19 testing strategies concluded that for outbreak control, the turnaround time of testing was a more critical factor than the analytical sensitivity of the assay itself [9]. This finding underscores a key advantage of LAMP and rapid antigen tests, which can provide results much faster than standard RT-PCR, thereby offering a significant public health benefit despite potentially lower sensitivity.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of RT-PCR, LAMP, and dPCR

| Parameter | RT-PCR / qPCR | LAMP | dPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Limit of Detection (LOD) | Varies; ~10-100 copies [36] | 1-10 copies/reaction [36] | Single copy detection [17] |

| Quantification Basis | Relative (Ct value vs. standard curve) | End-point or real-time (Time-positive) | Absolute (Poisson statistics) |

| Precision / Reproducibility | High | High | Superior, especially for low targets [17] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Moderate | Moderate (improved with Bst 3.0) [33] | High (due to partitioning) [17] |

| Assay Time (Amplification) | 1 - 2 hours | 15 - 60 minutes [36] | 1.5 - 3 hours (includes partitioning) |

| Throughput | High | Medium to High | Medium |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (with probe-based detection) | Low (challenging in single tube) [33] | Medium (limited by color channels) |

| Key Advantage | Gold standard, quantitative, multiplexable | Rapid, simple, equipment-free options | Absolute quantification, high precision |

Key Applications

RT-PCR and qPCR Applications

As the established gold standard, RT-PCR's applications are vast and foundational. It is indispensable for infectious disease diagnostics, including the detection of SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and RSV [17] [32]. It serves as a critical tool for gene expression analysis in research, allowing for the comparison of mRNA levels across different samples or conditions [32]. Furthermore, it is used in genetic testing for detecting mutations, SNPs, and in cancer research for profiling gene expression and translocations [31].

LAMP Applications

LAMP's speed and simplicity have led to its adoption in diverse fields where rapid, on-site testing is paramount. Its primary application is in infectious disease diagnostics, especially at the point-of-care for pathogens like COVID-19, tuberculosis, and malaria [35] [33]. It is extensively used in food safety testing for the rapid detection of contaminants like Salmonella and Listeria, enabling same-day results and reducing recall risks [35]. In veterinary diagnostics, LAMP allows for swift on-farm identification of diseases such as avian influenza and foot-and-mouth disease [35]. It is also increasingly applied in environmental monitoring for microbial contamination in water sources and in agriculture for detecting plant pathogens, such as those causing pea root rot, directly in the field [35] [34].

Digital PCR Applications

dPCR excels in applications requiring absolute quantification and high precision. It is particularly valuable for detecting rare genetic variants and low-abundance targets, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in liquid biopsies for oncology [17]. It is the preferred method for absolute quantification of viral loads without standard curves, providing more precise data for studies on viral dynamics and treatment efficacy [17]. dPCR is also used in gene expression analysis of low-abundance transcripts, copy number variation (CNV) analysis, and quality control of next-generation sequencing (NGS) libraries, where accurate quantification of input material is crucial [31].

Table 3: Key Application Fields for Each Technique

| Application Field | RT-PCR / qPCR | LAMP | dPCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Virology | Primary diagnostic tool (Gold Standard) [32] | Rapid point-of-care & screening [35] | Precise viral load monitoring [17] |

| Gene Expression | Standard for relative quantification [32] | Limited application | Absolute quantification of rare transcripts |

| Oncology Research | Mutation detection, expression profiling | Emerging for specific mutations | Rare allele detection (e.g., ctDNA), CNV |

| Food Safety & Veterinary | Used in central labs | Dominant for on-site/field testing [35] | Limited application |

| Environmental Monitoring | Standard lab-based testing | Portable, on-site detection [35] | Limited application |

| Research & NGS | Gene validation, QC | Target verification | Library quantification, QC [31] |

Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Detailed Protocol: Multi-Platform LAMP Assay for HAdV

A 2025 study established a robust multi-platform LAMP system for detecting Human Adenovirus types 3 and 7, providing an excellent example of a modern LAMP workflow [36].

- Primer Design: Primers were designed based on the conserved regions of the Hexon genes of HAdV-3 and HAdV-7, obtained from the NCBI database. A full set of LAMP primers was designed using PrimerExplorer V5, including outer primers (F3, B3), inner primers (FIP, BIP), and loop primers (LF, LB). For different detection platforms, primers were modified: for the immunochromatography (IC) method, the FIP primer was labeled with TAMRA and the LF primer with biotin; for the fluorescent probe method, a dual-labeled probe (HEX at 5' end, BHQ1 quencher at 3' end) was designed [36].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Total nucleic acids were extracted from clinical throat swab samples using a commercial nucleic acid extraction kit on an automated platform [36].

- LAMP Reaction Setup: The reaction was performed using a 2× RT-LAMP Premix. The 25 μL reaction mixture contained 12.5 μL of premix, 1 μL of primer mix (final concentrations: 1.6 μM each of FIP and BIP, 0.2 μM each of F3 and B3, 0.4 μM each of LF and LB), 2 μL of template DNA, and nuclease-free water up to the volume. For the fluorescent probe method, the dual-labeled probe was added [36].

- Amplification and Detection: The reaction was incubated at 63°C for 30 minutes. Detection was performed on three platforms:

- Calcein Method: The reaction mix included calcein. A color change from orange to green/yellow under UV light indicated a positive result.

- Immunochromatography (IC) Method: The biotin- and TAMRA-labeled amplicons were applied to a test strip. The appearance of both test and control lines indicated a positive result.

- Fluorescent Probe Method: Real-time fluorescence was monitored on a portable device [36].

Detailed Protocol: Comparative dPCR vs. RT-PCR for Respiratory Viruses

A 2025 study provided a direct comparative protocol for dPCR and real-time RT-PCR [17].

- Sample Collection: Respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal swabs and one BAL) were collected from symptomatic patients and stratified by Ct values into high (Ct ≤25), medium (Ct 25.1–30), and low (Ct >30) viral load categories [17].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: For both methods, RNA was extracted using automated commercial systems (KingFisher Flex for dPCR; STARlet for RT-PCR) with viral/pathogen nucleic acid kits [17].

- Real-Time RT-PCR Workflow: Extracted RNA was subjected to multiplex real-time RT-PCR using commercial respiratory panel kits targeting specific viral genes (Influenza A, B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2). Amplification and Ct value determination were performed on a standard thermocycler [17].

- Digital PCR Workflow: Extracted RNA was analyzed on a nanowell-based dPCR system (QIAcuity). The reaction mix, including primer-probe sets for the same targets and an internal control, was loaded into nanoplates, partitioning the sample into ~26,000 wells. End-point PCR was performed, and fluorescent signals were analyzed by the instrument's software to provide absolute copy numbers [17].

- Statistical Analysis: Data from both methods were analyzed descriptively. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the performance of dPCR and RT-PCR across the different viral load categories [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for Molecular Amplification Techniques

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Description | Example Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Strand-displacing DNA polymerase for isothermal amplification. Engineered versions (Bst 2.0, Bst 3.0) offer improved speed, stability, and RT activity [33]. | LAMP |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable DNA polymerase with 5'-3' polymerase activity; the workhorse enzyme for PCR. | RT-PCR, dPCR |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that synthesizes cDNA from an RNA template. | RT-PCR |

| dNTPs | Deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for DNA synthesis. | All |

| Primers & Probes | Oligonucleotides designed to specifically hybridize to the target sequence. Probes (TaqMan, Molecular Beacons) provide specificity in qPCR and dPCR [32]. | All |

| DNA Binding Dyes (SYBR Green) | Fluorescent dyes that intercalate into double-stranded DNA, allowing real-time detection of amplification [32]. | qPCR |

| Calcein / HNB Dye | Colorimetric indicators for visual detection of LAMP amplification. Calcein changes from orange to green; HNB changes from violet to sky blue [33] [36]. | LAMP |

| Commercial Premixes | Optimized master mixes containing buffer, enzymes, dNTPs, etc., for specific techniques (e.g., 2× RT-LAMP Premix [36]). | All |

The choice between RT-PCR, LAMP, and dPCR is not a matter of identifying a single superior technology, but rather of selecting the right tool for a specific application, considering the trade-offs between sensitivity, speed, cost, and operational requirements. RT-PCR remains the gold standard for versatile, quantitative analysis in centralized laboratories. LAMP has carved out a critical niche as a rapid, portable, and accessible technology for point-of-care and field-use settings, where speed and simplicity are paramount. dPCR provides the highest level of precision and absolute quantification, making it indispensable for advanced research and clinical applications where detecting rare events or achieving maximum accuracy is necessary. As innovations in polymerase engineering, primer design, and detection chemistries continue, the performance boundaries of all three techniques will expand, further solidifying their collective role in advancing research, public health, and clinical diagnostics.

Methodology in Action: Protocol Design and Pathogen Detection

The accuracy of molecular diagnostic tests for infectious diseases, including SARS-CoV-2, is highly dependent on two critical factors: the sample preparation methodology and the analytical technique employed. The broader thesis of sensitivity comparison between Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), nested PCR (nPCR), and Reverse Transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) research must account for substantial variability introduced during sample collection, processing, and nucleic acid extraction. This guide objectively compares the performance of these molecular techniques across different sample matrices, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison Across Sample Types

The diagnostic sensitivity of molecular assays varies significantly depending on the sample type and preparation method. The table below summarizes the comparative performance of RT-LAMP and RT-PCR (including real-time quantitative RT-PCR, or RT-qPCR) across different sample types, based on aggregated research findings.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Molecular Detection Methods Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Method | Key Performance Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracted RNA | RT-LAMP vs. RT-qPCR | Sensitivity comparable to RT-qPCR; 100% specificity reported in multiple studies. [20] [19] | |

| Direct Swabs | RT-LAMP vs. RT-qPCR | Lower sensitivity (71%) for RT-LAMP compared to RT-qPCR; requires optimized protocols. [19] | |

| Nasopharyngeal Swabs | RT-LAMP | Diagnostic sensitivity of 97.4% for samples with Ct ≤33; 100% for high viral loads (Ct ≤25). [37] | |

| Saliva | RT-LAMP vs. RT-qPCR | 93% agreement with RT-qPCR (Cohen’s kappa); viable alternative with simpler collection. [20] | |

| Stool/Feces | RT-LAMP vs. rRT-PCR | Overall diagnostic sensitivity of 62% (Ct ≤40); 100% sensitivity for high viral loads (Ct ≤25). [37] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the performance data, this section outlines the key experimental methodologies cited in the comparison.

Protocol: SARS-CoV-2 Detection in Extracted RNA via RT-LAMP and RT-qPCR

A 2024 study directly compared one-step real-time RT-PCR and one-step RT-LAMP using 342 clinical samples (nasopharyngeal and saliva). [20]

- Sample Preparation: Nasopharyngeal and saliva samples were collected in Viral Transport Medium (VTM). RNA was extracted using a commercial SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction kit. The process involved lysis, binding to a filter membrane, washing, and elution in a final volume of 100 µl. RNA purity and quantity were measured via nanodrop. [20]

- One-Step RT-qPCR: Reactions used a 20 µl volume with 5 µl of RNA template and master mix targeting the N gene (HEX channel) and RNase P as an internal control (ROX channel). Cycling conditions were: 50°C for 20 min; 95°C for 3 min; 45 cycles of 95°C for 15s and 55°C for 40s. [20]

- One-Step RT-LAMP: Primers targeted the N gene of SARS-CoV-2. Reactions used a 25 µl mixture containing 5 µl of RNA template, specific primer concentrations (40 pmol internal primers, 20 pmol loop primers, 5 pmol external primers), and Bst DNA/RNA Polymerase. Incubation was performed at 65°C for 45-60 minutes. [20]

Protocol: SARS-CoV-2 Detection in Direct Swab Samples

A 2023 study highlighted the challenge of using direct swabs without RNA extraction for RT-LAMP. [19]

- Sample Preparation: Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab samples were suspended in VTM. For "direct" assays, these swab samples were used without prior RNA extraction. [19]

- RT-LAMP Assay: The RT-LAMP method utilized a primer set targeting the ORF1a gene. The optimal incubation time was determined to be 45 minutes at 65°C. Results were read using fluorescence, agarose gel electrophoresis, and visual color change. [19]

- Comparison Method: A commercial RT-qPCR kit was used as the reference standard. The study found that while RT-LAMP was highly sensitive with extracted RNA, its sensitivity dropped to 71% when applied to direct swab samples. [19]

Protocol: SARS-CoV-2 Detection in Animal Feces via RT-LAMP

A 2025 study validated a commercial, colorimetric RT-LAMP assay for detecting SARS-CoV-2 in animal feces, a complex sample matrix. [37]

- Sample Type: Clinical fecal samples from various animal species.

- Comparator Assay: Real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR).

- RT-LAMP Assay: A pH-based, colorimetric RT-LAMP assay was used. The assay was robust across incubation lengths of 30-45 min and temperatures of 60-70°C.

- Key Findings: The assay showed 100% sensitivity for samples with high viral loads (rRT-PCR Ct ≤ 25) and 62% overall sensitivity (Ct ≤ 40). The limit of detection was determined to be 72 genome copies per reaction. [37]

Workflow and Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting a sample preparation and detection pathway based on research objectives and constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the described protocols relies on specific reagents and materials. The following table details essential solutions for this field of research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserves virus viability and nucleic acids during sample transport. | Used for collecting and transporting nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs. [20] [19] |

| Commercial RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies and concentrates viral RNA from complex sample matrices; critical for sensitivity. | Used in all protocols involving extracted RNA to isolate viral RNA from swabs, saliva, or stool. [20] [37] |

| Bst DNA/RNA Polymerase | The strand-displacing polymerase enzyme essential for the isothermal amplification in RT-LAMP. | A key component of the RT-LAMP master mix. [20] |

| LAMP Primers (Sets of 6) | Specifically designed primers (F3, B3, FIP, BIP, LF, LB) that recognize multiple target regions for highly specific amplification. | Designed to target genes such as N or ORF1a of SARS-CoV-2. [20] [38] |

| pH-Sensitive Dye (e.g., Phenol Red) | Allows visual, colorimetric readout of RT-LAMP results; proton release during amplification causes color change. | Enables naked-eye interpretation of results, turning from pink (negative) to yellow (positive). [39] [37] |

The choice between sample preparation methods and molecular diagnostic techniques involves significant trade-offs. RT-qPCR remains the gold standard for sensitivity, particularly for samples with low viral loads or complex matrices like stool. [37] [30] However, RT-LAMP presents a compelling alternative when rapid results, minimal equipment, and cost are primary concerns, especially in settings where high viral load screening is the goal. [9] [20] The key to maximizing sensitivity across all methods lies in the consistent use of robust nucleic acid extraction protocols, particularly when dealing with direct swabs or stool samples where inhibitors are present. Researchers must align their choice of sample preparation and detection methodology with the specific requirements of their diagnostic or research application.

Primer Design Strategies for SARS-CoV-2, Entamoeba histolytica, and Bacterial Resistance Genes