Modern Clinical Virology Diagnostics: Integrating PCR, Serology, and Emerging Technologies for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary viral diagnostic techniques, focusing on the principles, applications, and limitations of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serological assays.

Modern Clinical Virology Diagnostics: Integrating PCR, Serology, and Emerging Technologies for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary viral diagnostic techniques, focusing on the principles, applications, and limitations of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serological assays. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational science behind these methods, their practical implementation in clinical and research settings, strategies for optimization and troubleshooting, and their comparative validation. The content synthesizes current literature to address the critical need for accurate pathogen detection, seroprevalence studies, and therapeutic monitoring, while also examining the future trajectory of diagnostic technologies including high-throughput sequencing and their implications for biomedical innovation.

The Pillars of Viral Detection: Understanding PCR and Serology Fundamentals

In the field of clinical virology, the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) has revolutionized the detection and diagnosis of viral pathogens by enabling the exponential amplification of specific viral genetic material from minimal sample input. This core technology allows researchers and clinicians to identify infections with exceptional sensitivity and specificity, even during early stages when viral loads are low or in asymptomatic individuals [1]. Molecular detection techniques, primarily PCR and its advanced derivatives, have become foundational tools for diagnosing diseases such as COVID-19, monitoring treatment efficacy, and conducting public health surveillance [2] [3]. The principle of PCR revolves around the in vitro enzymatic replication of target DNA sequences through repetitive thermal cycling, facilitating the billion-fold amplification of a specific genomic region flanked by primer binding sites, which can then be detected and analyzed [2] [4]. This technical note details the methodological principles, procedural protocols, and key applications of PCR in viral detection, providing a framework for its implementation in research and diagnostic settings.

Fundamental Principles of PCR and Viral Genetic Material Amplification

The core objective of PCR in virology is to selectively amplify a unique sequence within a virus's genome, making detectable what was initially present in quantities too low for direct analysis. The process relies on the complementary base pairing of nucleotides (A-T and G-C for DNA) and a thermostable DNA polymerase to synthesize new DNA strands. Most human viral pathogens, however, are RNA viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2, Influenza), which necessitates an initial reverse transcription step to convert viral RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) before standard PCR amplification can begin [1]. This combined approach is referred to as Reverse Transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

The amplification process occurs in three fundamental steps that are repeated for 25-45 cycles [4]:

- Denaturation: The double-stranded DNA template is heated to ~95°C, causing the strands to separate.

- Annealing: The temperature is lowered to 50-65°C, allowing short, synthetic oligonucleotide primers to bind (anneal) to their complementary sequences on either side of the target viral gene.

- Extension: The temperature is raised to ~72°C, the optimal temperature for a thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase) to extend the primers by adding nucleotides to synthesize new DNA strands.

Each cycle theoretically doubles the amount of the target DNA sequence, leading to an exponential accumulation of the specific amplicon (the amplified product) that can be visualized, quantified, or sequenced [2].

Evolution of PCR Technologies in Viral Detection

Since its inception, PCR technology has diversified significantly, giving rise to advanced formats that enhance quantification, multiplexing, and absolute detection capabilities. The table below summarizes the key PCR methodologies and their relevance to clinical virology.

Table 1: Key PCR Methodologies and Their Applications in Viral Detection

| Technology | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Virology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional PCR | Endpoint detection of amplified DNA via gel electrophoresis. | Simplicity, low cost, equipment accessibility. | Qualitative detection of viral presence; cloning target genes [2]. |

| Nested PCR | Two consecutive amplification rounds with two primer sets. | Enhanced specificity and sensitivity; reduces false positives. | Detection of pathogens with low viral loads [2]. |

| Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) | Fluorescence-based monitoring of amplification in real-time. | High sensitivity, broad dynamic range, precise quantification of viral load. | Gold standard for diagnosis and monitoring of many viral infections (e.g., HIV, HCV, SARS-CoV-2) [2] [5] [1]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Partitioning of sample into thousands of individual reactions for absolute quantification. | Absolute quantification without standard curves; superior precision and sensitivity for low-abundance targets; high resistance to inhibitors. | Detection of low-level viremia, viral reservoir monitoring, and quantification of minor variants [6] [2]. |

| Multiplex PCR | Simultaneous amplification of multiple targets in a single reaction using multiple primer pairs. | High throughput, cost efficiency, capacity for co-infection detection and internal controls. | Panels for respiratory viruses (e.g., Influenza, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) and gastrointestinal viruses [2]. |

Performance Comparison: qPCR vs. dPCR

A recent 2025 study directly compared the performance of multiplex dPCR with qPCR for detecting periodontal pathobionts, providing insights applicable to viral load quantification. The findings are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparative Analytical Performance of dPCR versus qPCR [6]

| Performance Parameter | qPCR Performance | dPCR Performance | Implications for Viral Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity (R²) | High | >0.99 | Both methods show excellent correlation across a wide range of target concentrations. |

| Intra-assay Precision (CV%) | Lower | Higher (Median CV%: 4.5%) | dPCR provides more reproducible and reliable measurements between technical replicates. |

| Sensitivity at Low Loads | Prone to false negatives at <3 log10Geq/mL | Superior; reliably detects low copy numbers | dPCR is advantageous for detecting early infection or latent viruses with very low viral loads. |

| Accuracy & Agreement | Comparable at medium/high loads | Comparable at medium/high loads | Both methods are reliable for quantifying moderate to high viremia. |

| Quantification Basis | Relative to a standard curve | Absolute via Poisson statistics | dPCR eliminates the need for calibration curves, simplifying workflow and reducing potential variability. |

Experimental Protocols for PCR-Based Viral Detection

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

The accuracy of PCR begins with proper sample collection. For respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2, this typically involves a pharyngeal swab [1]. The swab is immediately placed in viral transport media and should be stored at -20°C or colder if processing is delayed. Viral RNA extraction is then performed using commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini kit) or automated extraction systems, which isolate and purify nucleic acids from proteins, inhibitors, and other cellular debris [6] [1]. The purity and concentration of the extracted RNA/DNA should be verified using a spectrophotometer [1].

Reverse Transcription and PCR Amplification

For RNA viruses, the purified RNA is converted to cDNA. A typical reaction uses a reverse transcriptase enzyme (e.g., SuperScript III), dNTPs, and either random hexamers or gene-specific primers [1].

The following protocol details a standard setup for a real-time PCR (qPCR) reaction, which is the workhorse for modern viral diagnostics.

Table 3: Standard qPCR Reaction Setup [4] [1]

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Master Mix (2X) | 10 µL | Contains Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and optimized buffer. |

| Forward Primer | 0.2 - 0.4 µM | Binds to the complementary sequence on one strand of the target DNA. |

| Reverse Primer | 0.2 - 0.4 µM | Binds to the complementary sequence on the opposite strand. |

| Hydrolysis Probe (e.g., TaqMan) | 0.1 - 0.2 µM | Provides sequence-specific fluorescence signal during amplification. |

| Template DNA/cDNA | 2-5 µL | The sample containing the target viral genetic sequence. |

| Nuclease-free Water | To 20 µL | Adjusts the final reaction volume. |

Thermal Cycling Protocol:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes (activates polymerase, denatures template).

- Amplification Cycle (Repeat 40-45 times):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 58-60°C for 30-60 seconds (temperature and duration depend on primer/probe design). Fluorescence is measured at this step.

- Final Hold: 4°C for ∞.

Primer and Probe Design Guidelines

False-positive results can occur with unoptimized primer sets, highlighting the critical need for careful design and validation [1]. The following three-step guideline ensures specificity and sensitivity:

- Target Selection: Select highly conserved and unique regions within the viral genome (e.g., RdRP, N, E, and S genes for SARS-CoV-2) to ensure specificity and avoid cross-reactivity with human or other microbial genomes [1].

- In Silico Validation: Analyze primer and amplicon sequences using software (e.g., Oligo 7, DNASTAR Lasergene) to check for secondary structures, self-dimers, heterodimers, and ensure optimal melting temperatures (Tm) [7] [1].

- Experimental Optimization: Empirically test primer concentrations and annealing temperatures to maximize specific amplification and eliminate spurious primer-dimer artifacts [1].

Advanced Considerations and Troubleshooting

Challenges in Multi-Template PCR

In applications like multiplex PCR or viral metagenomics, simultaneous amplification of multiple targets can lead to skewed abundance data due to sequence-specific differences in amplification efficiency [8]. Recent advances use deep learning models (1D-CNNs) to predict a sequence's amplification efficiency based on its sequence alone, identifying motifs that lead to poor amplification. This allows for the design of better assays and more accurate quantitative results [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCR-Based Viral Detection

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme for DNA synthesis during PCR amplification. | Core enzyme in standard and real-time PCR protocols [4]. |

| QIAcuity dPCR Kit (Qiagen) | Reagents and nanoplate for performing digital PCR. | Absolute quantification of viral load with high precision [6]. |

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Silica-membrane technology for purification of viral DNA/RNA. | Nucleic acid extraction from clinical swab samples [6]. |

| SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System | Reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA. | Essential first step for detecting RNA viruses via RT-PCR [1]. |

| Primer/Probe Sets | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target binding and detection. | Detection of specific viral genes (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 E-gene) [1]. |

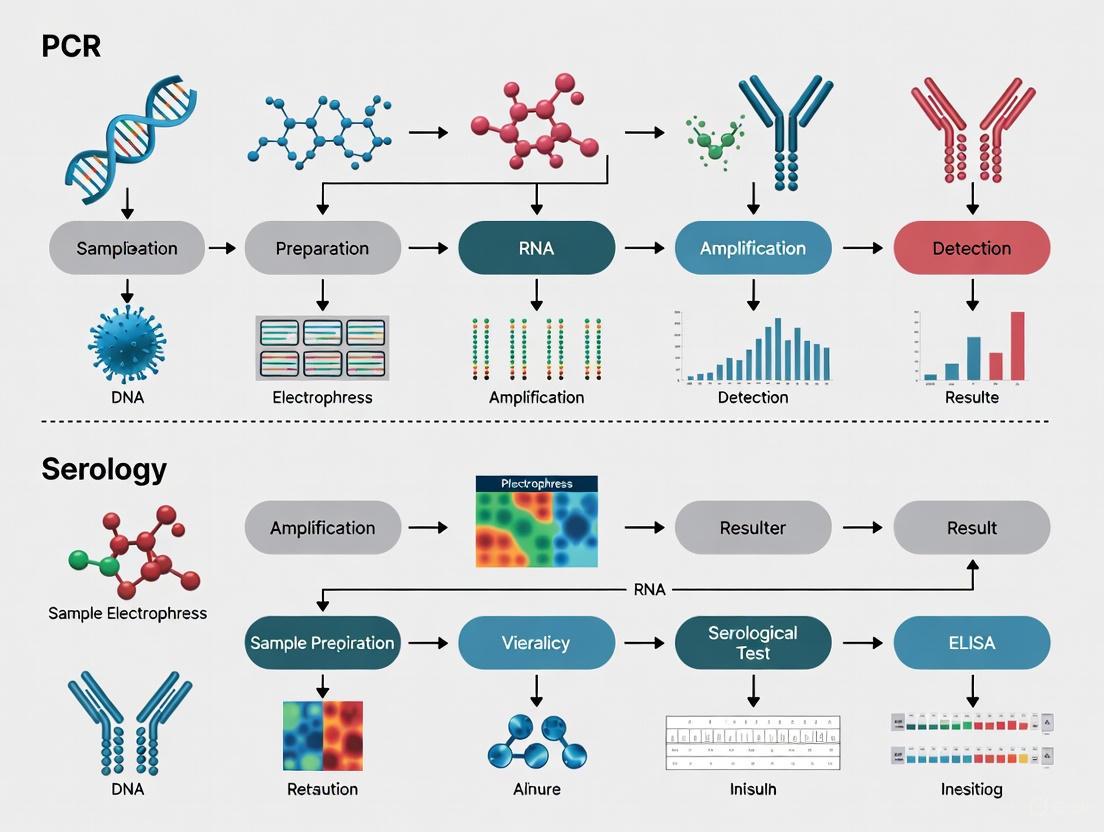

Workflow Diagram: PCR in Viral Detection

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for molecular detection of viruses using RT-qPCR, from sample collection to result interpretation.

Diagram 1: Viral Detection via RT-qPCR Workflow. The process begins with sample collection and proceeds through nucleic acid extraction, reverse transcription, and cyclic amplification with fluorescence detection.

PCR and its advanced derivatives constitute the cornerstone of modern molecular virology, providing powerful tools for the sensitive, specific, and rapid detection of viral pathogens. From the quantitative power of qPCR to the absolute precision of dPCR, these techniques enable not only clinical diagnosis but also epidemic surveillance, treatment monitoring, and fundamental viral research. As the field progresses, integration with microfluidics, point-of-care technologies, and artificial intelligence for assay optimization promises to further enhance the speed, accessibility, and accuracy of viral molecular detection, solidifying its role as an indispensable asset in global public health [2] [9] [8].

Serology, the scientific study of blood serum and other bodily fluids, plays a fundamental role in clinical virology by detecting pathogen-specific antibodies that serve as biomarkers of past exposure to viruses, bacteria, or parasites [10]. These immunological methods rely on precise antigen-antibody interactions, where antibodies recognize and bind to unique molecular targets on pathogens called epitopes [11] [12]. The binding occurs through complementary shapes and intermolecular forces including Van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonds, and electrostatic attractions, with the strength of these forces determining the antibody's affinity [12].

Antibodies exist as one or more copies of a Y-shaped unit composed of four polypeptide chains: two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains [12]. The top of the Y shape contains the variable region (fragment antigen-binding or F(ab) region) that binds specifically to antigens, while the base consists of constant domains forming the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region that mediates immune cell interactions [12]. In mammals, antibodies are divided into five isotypes (IgG, IgM, IgA, IgD, and IgE) based on their heavy chain type, with each isotype exhibiting distinct biological properties, functional locations, and capabilities for dealing with different antigens [12].

Antibody Isotypes in Diagnostic Virology

Structural and Functional Characteristics

The five antibody isotypes demonstrate significant structural and functional diversity critical for their roles in immune defense and diagnostic detection:

Table 1: Structural and Functional Properties of Antibody Isotypes

| Isotype | Heavy Chain | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Structure | Primary Functions and Diagnostic Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | γ (gamma) | 150 | Monomer | Most abundant serum antibody (~75% of total serum antibodies); provides majority of antibody-based immunity; moderate complement fixer; indicates recent or past infection [12]. |

| IgM | μ (mu) | 900 | Pentamer | First antibody produced in primary immune response; high avidity; eliminates pathogens in early stages before sufficient IgG production; indicates recent/active infection [12]. |

| IgA | α (alpha) | 150-600 | Monomer-tetramer | Predominantly found in mucosal areas (gut, respiratory, urogenital tracts); prevents pathogen colonization; resistant to digestion; secreted in milk [12]. |

| IgD | δ (delta) | 150 | Monomer | Function unclear; works with IgM in B cell development; primarily B-cell bound [12]. |

| IgE | ε (epsilon) | 190 | Monomer | Binds to allergens; triggers histamine release from mast cells; involved in allergic reactions and protection against parasitic worms [12]. |

Temporal Dynamics of Antibody Responses

The diagnostic utility of different antibody isotypes relies heavily on their distinct temporal emergence patterns following infection:

Figure 1: Temporal Sequence of Antibody Responses Following Infection. IgM antibodies appear first, typically within 3-7 days post-infection, serving as markers of recent or active infection. IgG antibodies emerge later (7-14 days), peak around 3-6 weeks, and often persist for months or years, indicating longer-term immunity or past exposure [10] [12].

Application in SARS-CoV-2 Detection: A Case Study

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical importance of understanding serological responses, with extensive research illuminating the performance characteristics of various antibody detection methods for SARS-CoV-2.

Comparative Performance of Serological Assays

Table 2: Diagnostic Accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 Serological Assays in Clinical Practice

| Assay Type | Target Epitope | Antibody Type | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Neutralizing Antibody Sensitivity (%) | Neutralizing Antibody Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-N ECLIA | Nucleocapsid (N) | Pan-Ig | 86.8 | 98.4 | 91.7 | 93.0 |

| Anti-S1 ELISA | S1 spike domain | IgG | 86.2 | 98.2 | 92.7 | 92.0 |

| Anti-S1/S2 CLIA | S1/S2 spike domains | IgG | 84.7 | 97.6 | 90.3 | 97.7 |

| Anti-RBD+LFI | Receptor-binding domain | Pan-Ig | 84.0 | 96.1 | 87.9 | 97.9 |

| Anti-N CLIA | Nucleocapsid (N) | IgG | 81.0 | 98.3 | 84.1 | 100.0 |

| Anti-RBD ELISA | Receptor-binding domain | IgG | 79.2 | 97.2 | 85.8 | 95.9 |

| Anti-N ELISA | Nucleocapsid (N) | IgG | 65.6 | 97.7 | 66.2 | 65.3 |

Data adapted from a prospective cross-sectional study of 2,573 healthcare workers and 1,085 inpatients at a Swiss University Hospital [13].

Comparative Analysis of Detection Methods

Research conducted across university settings in Cameroon demonstrated distinct performance patterns between molecular and serological testing approaches. In a study of 291 participants, the overall COVID-19 PCR-positivity rate was 21.31% (62/291), while overall IgG seropositivity (IgM−/IgG+ and IgM+/IgG+) was 24.4% (71/291) [14]. Notably, 26.92% (7/26) of participants with COVID-19 IgM+/IgG− had negative PCR results versus 73.08% (19/26) with positive PCR, and 17.65% (6/34) with COVID-19 IgM+/IgG+ had negative PCR compared to 82.35% with positive PCR (28/34) [14]. Additionally, 7.22% (14/194) with IgM−/IgG− had positive PCR, highlighting the complex relationship between viral presence and antibody responses [14].

A study of 133 hospitalized COVID-19 patients revealed important performance differences, with IgM antibody tests showing higher positive rates (79.55%, 82.69%, and 72.97% in moderate, severe, and critical cases, respectively) compared to RT-PCR detection (65.91%, 71.15%, and 67.57% in the same groups) [15]. IgG positivity rates were substantially higher across all severity categories (93.18%, 100%, and 97.30% in moderate, severe, and critical cases, respectively) [15].

Significant variability in test performance has been observed across different testing platforms. A comparison of immunochromatography (ICG) rapid test kits and chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) quantitative antibody tests demonstrated substantial discrepancies, with only 2 of 51 staff members who were IgM-positive by rapid testing confirming positive by CLIA, and only 6 of 56 IgG-positive rapid tests confirming by CLIA [16].

Essential Protocols for Serological Detection

Comprehensive Protocol for Antibody Detection in Viral Diagnostics

Principle: This protocol outlines the procedure for detecting virus-specific IgM and IgG antibodies in human serum or plasma samples using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methodology, which can be adapted for various viral pathogens.

Materials and Reagents:

- Coating buffer (0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6)

- Washing buffer (PBS with 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.4)

- Blocking buffer (PBS with 1% BSA or 5% non-fat dry milk)

- Viral antigens (recombinant proteins or inactivated virus)

- Test serum samples (heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 minutes)

- Reference positive and negative control sera

- Anti-human IgM and IgG antibodies conjugated to enzyme (HRP or AP)

- Enzyme substrate (TMB for HRP, pNPP for AP)

- Stop solution (1M H₂SO₄ for TMB, 1M NaOH for pNPP)

Procedure:

- Antigen Coating: Dilute viral antigen in coating buffer to optimal concentration (typically 1-10 μg/mL). Add 100 μL per well to microtiter plate. Incubate overnight at 4°C or 2 hours at 37°C.

Washing: Aspirate liquid from wells and wash three times with washing buffer (300 μL per well). Tap plate dry on absorbent paper between washes.

Blocking: Add 200 μL blocking buffer per well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at 37°C. Wash as in step 2.

Sample Incubation: Dilute test sera in blocking buffer (typically 1:100 to 1:1000). Add 100 μL per well in duplicate. Include positive and negative controls. Incubate 1-2 hours at 37°C. Wash as in step 2.

Conjugate Incubation: Add anti-human IgM (μ-chain specific) or IgG (γ-chain specific) antibody conjugated to enzyme at optimal dilution in blocking buffer. Incubate 1 hour at 37°C. Wash as in step 2.

Substrate Development: Add 100 μL substrate solution per well. Incubate in dark for 10-30 minutes at room temperature.

Reaction Termination: Add 50 μL stop solution per well.

Measurement: Read absorbance at appropriate wavelength (450 nm for TMB, 405 nm for pNPP) using microplate reader.

Interpretation: Calculate cutoff value based on negative control absorbance (typically mean + 3 standard deviations). Samples with absorbance above cutoff are considered positive.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- High background: Increase blocking time or change blocking agent; optimize conjugate dilution; increase wash cycles or washing stringency.

- Low signal: Check reagent expiration; optimize antigen coating concentration; increase sample incubation time or temperature.

- High variation between duplicates: Ensure consistent washing; check pipette calibration; confirm proper sample mixing.

Rapid Lateral Flow Immunoassay Protocol

Principle: This protocol describes the procedure for rapid detection of viral antibodies using immunochromatographic lateral flow devices, suitable for point-of-care testing.

Materials:

- Lateral flow test devices

- Serum, plasma, or whole blood samples

- Sample diluent buffer

- Timer

Procedure:

- Allow test devices and samples to reach room temperature (15-30°C).

- Add specified volume of sample (typically 10-20 μL) to sample well.

- Immediately add specified volume of diluent buffer (typically 2-3 drops).

- Start timer and read results at specified time (typically 10-20 minutes).

- Do not interpret results after maximum reading time (typically 30 minutes).

Interpretation:

- IgM Positive: Control line and IgM test line visible

- IgG Positive: Control line and IgG test line visible

- IgM and IgG Positive: Control line and both test lines visible

- Negative: Only control line visible

- Invalid: Control line not visible, regardless of test lines

Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (CLIA) Protocol

Principle: This automated protocol utilizes chemiluminescent detection for high-sensitivity quantitative measurement of antibody levels.

Materials:

- CLIA analyzer and compatible reagent kits

- Sample diluent

- Calibrators and controls

- Reaction vessels

Procedure:

- Follow manufacturer's instructions for instrument preparation and initialization.

- Load samples, calibrators, and controls into designated positions.

- The automated system performs:

- Sample and reagent dispensing

- Incubation

- Magnetic separation/washing

- Substrate addition

- Luminescence measurement

- Results are calculated automatically based on calibration curve.

- Report quantitative results in standardized units (AU/mL, BAU/mL, or IU/mL).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Serological Assay Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Antigens | Recombinant spike protein (S1, S2, RBD), nucleocapsid protein, inactivated whole virus | Coating antigen for capturing specific antibodies; choice of antigen affects test performance [13] |

| Detection Antibodies | Anti-human IgM (μ-chain specific), anti-human IgG (γ-chain specific), enzyme conjugates (HRP, AP), fluorescent conjugates | Secondary detection; binds to human antibodies of specific isotypes; enzyme conjugates enable colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent detection [11] [12] |

| Assay Controls | Known positive and negative serum samples, international reference standards, calibrators | Quality control, standardization, calibration of quantitative assays, determination of cutoff values [13] |

| Signal Generation | TMB (3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine), pNPP (p-nitrophenyl phosphate), AMPPD (3-(2'-spiroadamantane)-4-methoxy-4-(3''-phosphoryloxy)phenyl-1,2-dioxetane) | Enzyme substrates that generate measurable color (TMB, pNPP) or light (AMPPD) upon enzymatic conversion [11] |

| Carrier Proteins | Bovine serum albumin (BSA), keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) | Used as carrier proteins for haptens; blocking agents to reduce nonspecific binding [12] |

Diagnostic Workflow and Strategic Implementation

The effective implementation of serological testing requires careful consideration of the diagnostic question being addressed and appropriate test selection:

Figure 2: Diagnostic Decision Pathway for Serological Testing. The appropriate testing strategy depends on the clinical or epidemiological question. Molecular methods (PCR) remain superior for detecting active infection, while serological approaches provide valuable information for assessing past exposure, population immunity, and in some cases, complementing molecular testing for active infection diagnosis [14] [10] [13].

Serological testing provides distinct advantages for epidemiological surveillance by capturing both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases irrespective of healthcare-seeking behavior, as antibody profiles maintain a trace of past exposure even after pathogen clearance [10]. This makes serological data particularly valuable for understanding true infection burden, transmission dynamics, and population immunity levels, especially when implemented as part of comprehensive public health surveillance strategies [10].

Accurate and timely diagnosis is a cornerstone of effective clinical management and control of viral infections. The reliability of diagnostic results is fundamentally governed by three interconnected biological and immunological phenomena: viral shedding, the diagnostic window period, and seroconversion. Viral shedding refers to the expulsion and release of virus progeny from an infected host, which can occur through various routes such as respiratory droplets, feces, or other bodily fluids [17]. The window period describes the time between infection and the point at which a test can reliably detect the infection [18]. Seroconversion is the specific immune process where an individual develops detectable antibodies in response to an infection or vaccination [19] [20] [18].

Navigating the complex temporal relationships between these three processes is critical for diagnostic accuracy, appropriate patient isolation, and effective treatment initiation. This application note provides a structured overview of these concepts, supported by quantitative data and detailed protocols, to guide researchers and scientists in the field of clinical virology.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Viral Shedding Dynamics

Viral shedding is the process by which infected individuals release viral particles into the environment. The duration and site of shedding are highly variable among different viruses and can profoundly impact epidemiological tracking.

- Prolonged Post-Recovery Shedding: For some pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, viral shedding, particularly from the gastrointestinal tract, can continue for weeks to months after clinical recovery and the cessation of symptoms. This prolonged shedding complicates the interpretation of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE), as the viral signal in sewage can be dominated by recovered individuals rather than actively infectious cases [17].

- Infectiousness Correlation: In many diseases, the peak of infectiousness often occurs before seroconversion. However, viral shedding can continue after seroconversion, potentially extending the contagious period [19].

Seroconversion and the Immune Response

Seroconversion is a key event in the adaptive immune response, marking the transition from a seronegative to a seropositive status for a specific pathogen.

- Mechanism: When a pathogen enters the body, its antigens activate B cells. These B cells begin producing antibodies, first typically of the Immunoglobulin M (IgM) class, followed by a switch to the more specific and durable Immunoglobulin G (IgG) class [18]. Standard serological tests can only detect these antibodies once their concentration in the serum is sufficiently high to be measured [18].

- Atypical Patterns: While IgM usually appears before IgG, some infections, including COVID-19, can deviate from this pattern, with IgM appearing after IgG, simultaneously, or sometimes not at all [19] [18].

- Clinical Implications: Seroconversion does not automatically equate to sterilizing immunity. The protection conferred by antibodies can be complete, partial, or temporary, depending on the pathogen and the individual's immune response [19] [18].

The Diagnostic Window Period

The window period is a critical concept for diagnostic testing, defined as the interval after infection during which a specific test cannot yet detect markers of the pathogen (either the pathogen itself or the immune response to it) [18].

- Serological Window Period: For antibody tests, the window period is the time between infection and seroconversion, when antibody levels become detectable. During this phase, an infected individual will test negative on an antibody test despite being infected [18].

- Antigen/Nucleic Acid Test Window Period: Antigen and Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs), such as PCR, can typically detect an infection earlier because they identify the virus directly, before an antibody response has mounted [21] [22].

- Impact on Diagnosis: The window period is a major source of false-negative results. For HIV, the window period for fourth-generation antigen/antibody tests can be around 14-18 days, meaning individuals can be highly infectious yet test negative during this time [22].

The relationship between viral load, antibody development, and test sensitivity across the timeline of infection is illustrated below.

Quantitative Data and Comparative Analysis

Impact of Season-Specific PCR Panels on Diagnostic Timelines

A 2025 prospective study on emergency department pneumonia diagnostics compared traditional culture methods with season-specific multiplex PCR panels. The quantitative outcomes demonstrate the profound impact of modern molecular techniques on the diagnostic timeline [21].

Table 1: Comparative Diagnostic Performance of Traditional Culture vs. Seasonal PCR Panels for Pneumonia [21]

| Performance Metric | Spring Season | Autumn-Winter Season | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Turnaround Time (Traditional) | 48 hours | 50 hours | - |

| Median Turnaround Time (PCR Panel) | 12 hours | 14 hours | p < 0.001 |

| Time Saved (Median Difference) | 36 hours | 36 hours | 95% CI: -42 to -30 |

| Diagnostic Yield (Traditional) | 61.6% | 56.8% | - |

| Diagnostic Yield (PCR Panel) | 80.6% | 80.0% | p < 0.01 |

| Risk Difference in Yield | +19.0 percentage points | +23.2 percentage points | - |

The data show that PCR panels slashed the time to pathogen identification by approximately three-fourths and significantly increased the likelihood of identifying the causative agent [21].

Seroconversion and Window Periods in Key Viral Infections

The timing of seroconversion and the length of the window period vary significantly by pathogen and the type of assay used.

Table 2: Seroconversion and Diagnostic Window Periods for Selected Viruses

| Virus / Infection | Time to Seroconversion (Typical) | Key Antibody Classes | Notes on Window Period & Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | IgM: Median 5 days post-symptom.\nIgG: Median 14 days post-symptom [18]. | IgM, IgG | Atypical patterns common (IgG before/with IgM). Higher viral load linked to earlier seroconversion [19]. NAAT is gold standard for acute diagnosis. |

| HIV | 2-4 weeks for antibody detection. p24 antigen appears earlier [22]. | IgM, IgG (p24 antigen) | 4th gen Ag/Ab tests shorten window to ~14 days [22]. NAAT (RNA test) is definitive during window period or discordant serology [22]. |

| General Pattern | Days to weeks, depending on pathogen and host. | IgM (acute phase), IgG (long-term) | The "window period" for antibody tests is pre-seroconversion. NAATs can detect infection before seroconversion [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating a Seasonal Multiplex PCR Panel for Respiratory Pathogens

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 clinical study evaluating rapid PCR panels for pneumonia diagnosis against traditional culture [21].

1. Objective: To assess the performance of season-specific multiplex PCR panels in accelerating pathogen identification and improving antibiotic stewardship in pneumonia patients.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Sample Type: Lower respiratory tract samples (e.g., sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage).

- Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit: A commercial kit for automated or manual nucleic acid extraction.

- PCR Master Mix: A multiplex RT-PCR master mix suitable for the platform.

- Season-Specific PCR Panel: Two customized panels targeting prevalent seasonal pathogens (see Table 3).

- Platform: A real-time PCR instrument capable of multiplex detection.

- Controls: Positive and negative extraction controls, as well as positive and no-template controls (NTC) for the PCR run.

Table 3: Example Composition of Seasonal PCR Panels [21]

| Pathogen Type | Spring Panel Targets | Autumn-Winter Panel Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Viruses | Influenza A/B, Parainfluenza, Rhinovirus/Enterovirus, Adenovirus | Influenza A/B, Human Metapneumovirus, Rhinovirus/Enterovirus, Seasonal Coronavirus, RSV A/B |

| Bacteria | Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila | Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Klebsiella pneumoniae |

3. Procedure: 1. Sample Collection and Processing: Collect respiratory samples from enrolled patients using sterile techniques. Homogenize sputum samples if necessary. 2. Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) from 200 µL of sample according to the manufacturer's instructions. Elute in a defined volume (e.g., 60-100 µL). 3. PCR Setup: * Thaw all reagents and keep on ice. * Prepare the PCR reaction mix according to the panel's instructions. A typical 25 µL reaction might include: 12.5 µL of 2x Master Mix, 2.5 µL of primer-probe mix, 5 µL of nuclease-free water, and 5 µL of extracted template DNA/RNA. * Load the plate onto the real-time PCR instrument. 4. Amplification: Run the thermocycling protocol as defined by the panel manufacturer. A typical program includes: Reverse transcription (if needed, 10-15 min at 50°C), initial denaturation (2 min at 95°C), followed by 40-45 cycles of denaturation (15 sec at 95°C) and combined annealing/extension (30-60 sec at 60°C). 5. Result Analysis: Analyze the amplification curves. Determine the presence or absence of each pathogen based on the cycle threshold (Ct) value and the pre-defined parameters of the assay.

4. Data Analysis: * Calculate the turnaround time from sample receipt to final report for both the PCR panel and the parallel traditional culture. * Calculate the diagnostic yield (proportion of tests identifying ≥1 pathogen) for both methods. * Compare the appropriateness of empiric antibiotic therapy based on PCR results versus standard care.

Protocol: Navigating Discordant HIV Serology Using a NAAT-Based Algorithm

This protocol is based on a 2025 case series highlighting the importance of NAAT in resolving discordant HIV screening results [22].

1. Objective: To establish a diagnostic algorithm for confirming HIV infection in patients with reactive screening tests but potential serological discordance, minimizing time to diagnosis.

2. Materials and Reagents: * Screening Tests: Fourth-generation HIV antigen/antibody immunoassay (e.g., Elecsys HIV combi PT or HIV Duo). * Rapid Test: Colloidal gold immunochromatographic assay (GICA) for HIV-1/2 antibodies. * Confirmatory Test: Western Blot (WB) or line immunoassay for HIV-1 antibodies. * NAAT Test: Quantitative or qualitative HIV-1 RNA PCR test (e.g., Roche cobas system).

3. Procedure & Decision Algorithm: The following workflow visualizes the steps for resolving discordant HIV test results, which can significantly reduce the diagnostic timeline from 11 days to 5-6 days [22].

4. Key Considerations: * Speed of Diagnosis: As demonstrated in the case series, the algorithm that triggers concurrent NAAT and Western Blot testing (right branch) upon initial serological discordance can reduce the time to definitive diagnosis by more than half compared to a sequential testing algorithm [22]. * Clinical Correlation: Always correlate laboratory findings with clinical presentation, CD4+ T-lymphocyte count, and patient history.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Viral Diagnostics and Serology Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex PCR Panels | Simultaneous detection of multiple pathogens in a single reaction. | Customized for seasonal pathogens (e.g., respiratory panels for spring vs. winter) [21]. |

| Fourth-Generation HIV Ag/Ab Assay | Screening test that detects both HIV p24 antigen and antibodies, shortening the diagnostic window period. | Elecsys HIV combi PT (single result) or HIV Duo (differentiated results) [22]. |

| NAAT Kit (e.g., RT-PCR) | Gold standard for direct detection of viral RNA/DNA; crucial for confirmation during the window period. | Used for SARS-CoV-2 and HIV-1 RNA detection. Provides definitive diagnosis in serologically discordant cases [21] [22]. |

| Colloidal Gold Immunochromatographic Assay (GICA) | Rapid, point-of-care test for antibody detection. Used for initial retesting in some diagnostic algorithms. | Can yield reactive results even when differentiated immunoassays show non-reactive antibodies, influencing the diagnostic pathway [22]. |

| Western Blot (WB) Kit | Confirmatory test for antibodies. Differentiates specific antibody reactions against individual viral proteins. | Considered a key confirmatory test for HIV in many guidelines, but can be slow. Indeterminate results require NAAT follow-up [22]. |

| ELISA Kit | Detects and quantifies specific antibodies (e.g., IgG, IgM) in serum. Used for seroprevalence studies. | Can be used in combination with pseudotyped viral particle-based entry assays to study seroconversion without live virus [19]. |

The diagnostic timeline of a viral infection is a dynamic interplay of virological and immunological events. Understanding the phases of viral shedding, the constraints of the window period, and the process of seroconversion is non-negotiable for accurate diagnosis and effective public health intervention. The data and protocols presented herein underscore that modern diagnostics, particularly rapid NAAT and sophisticated multiparametric serological assays, are powerful tools for navigating this timeline. Their strategic application, guided by a deep knowledge of the underlying biology, enables researchers and clinicians to shorten diagnostic delays, optimize therapeutic strategies, and ultimately improve patient outcomes. Future advancements will likely focus on integrating these technologies into even faster, point-of-care platforms and leveraging artificial intelligence to better interpret complex diagnostic data within the clinical context.

In clinical virology and infectious disease research, two fundamental diagnostic approaches are employed: direct detection of the pathogen itself and indirect detection of the host's immune response. Direct methods, primarily through polymerase chain reaction (PCR), identify microbial nucleic acids, confirming the presence of the pathogen. Indirect methods, notably serology, detect host-derived antibodies (IgG, IgM, IgA) produced in response to infection. The choice between these methods profoundly impacts diagnostic accuracy, clinical decision-making, and therapeutic intervention, necessitating a clear understanding of their respective principles, applications, and limitations within a research context [23] [24].

Core Principles and Key Distinctions

Direct and indirect testing methods operate on fundamentally different biological principles, which dictates their appropriate application in the diagnostic workflow.

Direct Testing aims to identify the pathogen itself within a host sample. It involves the detection of specific pathogen components, such as microbial DNA, RNA, proteins, or even intact organisms. A primary example is PCR, which amplifies microbial DNA to detectable levels, offering high specificity and confirmation of active infection when the pathogen is present in the sample [23] [25].

Indirect Testing, in contrast, evaluates the host's immune system response to the pathogen. Instead of detecting the microbe, these tests identify antibodies (e.g., IgM, IgG, IgA) produced by the host's adaptive immune system. The presence of specific antibodies indicates exposure to a pathogen at some point, but does not necessarily confirm an active, ongoing infection [23] [24].

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Direct and Indirect Diagnostic Methods

| Feature | Direct Detection (e.g., PCR) | Indirect Detection (Serology) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Analytic | Pathogen nucleic acids (DNA/RNA), antigens, or whole organism [23] | Host-produced antibodies (IgM, IgG, IgA, etc.) [26] |

| What a Positive Result Confirms | Presence of the pathogen in the sample [23] | An immune response has occurred; indicates exposure [24] |

| Optimal Use Case | Confirming active, ongoing infection [23] [27] | Determining past exposure, immune status, or late-presenting infections [27] [24] |

| Key Advantage | High specificity; definitive evidence of pathogen presence [23] | Can detect infection even if pathogen is not present in the sampled fluid [24] |

| Key Limitation | May miss infection if pathogen load is low or not in sampled compartment [23] | Cannot distinguish between active and past infection; relies on competent host immune response [23] [26] |

The relationship between these diagnostic pathways and the infection timeline is crucial for interpretation. The following diagram outlines the general workflow and logical decision points for applying each method.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol A: Direct Pathogen Detection via Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR (qPCR) is a gold standard direct detection method that allows for the simultaneous amplification and quantification of target nucleic acids [25]. This protocol is adapted for the detection of viral pathogens from respiratory samples.

Workflow Overview:

- Sample Collection & Nucleic Acid Extraction: Using sterile swabs, collect nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal samples. Place the swab in viral transport media. Extract DNA/RNA using commercial kits, ensuring purification from inhibitors like hemoglobin or heparin [25].

- Reverse Transcription (if targeting RNA virus): For RNA viruses, synthesize complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase enzyme [25].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing:

- Thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase)

- dNTPs

- Sequence-specific forward and reverse primers (20-25 nucleotides long)

- Fluorescent probe (e.g., TaqMan) or intercalating dye

- Magnesium chloride and reaction buffer

- Add extracted template DNA/cDNA.

- Amplification & Detection in Thermal Cycler:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes.

- 40-50 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Annealing: 55-72°C for 30-60 seconds (primer-specific).

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds. Fluorescence is measured at the end of each annealing/extension phase.

- Data Analysis: The quantification cycle (Cq), the cycle number at which fluorescence crosses a predefined threshold, is determined. A positive result is indicated by amplification within a valid Cq range. The Cq value is inversely proportional to the target amount [25].

Protocol B: Indirect Serological Detection via ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a widely used serological method to detect and quantify pathogen-specific antibodies in patient serum [28].

Workflow Overview for Indirect IgG ELISA:

- Coating: Coat a microtiter plate with a purified pathogen-specific antigen (e.g., viral spike or nucleocapsid protein). Incubate overnight, then wash and block to prevent non-specific binding.

- Sample Incubation: Add patient serum (diluted appropriately) and control sera to the wells. Pathogen-specific IgG antibodies will bind to the immobilized antigen. Incubate and wash thoroughly.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., anti-human IgG conjugated to Horseradish Peroxidase - HRP). This antibody binds to the patient IgG. Incubate and wash.

- Substrate Addition & Signal Detection: Add a chromogenic enzyme substrate (e.g., TMB for HRP). The enzyme converts the substrate, producing a color change.

- Result Interpretation: Stop the reaction and measure the absorbance. The intensity of the color (absorbance) is proportional to the amount of pathogen-specific antibody present in the sample. Results are reported as positive, negative, or equivocal based on comparison to calibrators and controls [28].

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The diagnostic performance of serological and molecular methods varies significantly based on the pathogen, infection stage, and assay design. A meta-analysis of COVID-19 serological assays revealed a wide range of accuracy, which can be quantitatively compared using the Diagnostic Odds Ratio (DOR). The DOR represents the odds of a positive test result in an infected individual versus the odds of a positive result in a non-infected individual; a higher DOR indicates better discriminatory power [5].

Table 2: Comparative Diagnostic Accuracy of Serological Assays and Methods

| Assay / Method | Target Antibody & Antigen | Pooled Diagnostic Odds Ratio (DOR) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 (Roche) | Total Antibody / Nucleocapsid (N) | 1,701.56 | Highest overall test accuracy among compared serological assays [5] |

| Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 N (Roche) | IgG / Nucleocapsid (N) | 1,022.34 | Superior diagnostic efficacy of anti-N antibodies [5] |

| Abbott SARS-CoV-2 IgG | IgG / Nucleocapsid (N) | 542.81 | High DOR for anti-N IgG assays [5] |

| LIAISON SARS-CoV-2 IgG (DiaSorin) | IgG / Spike (S1/S2) | 178.73 | Good performance for anti-spike protein assay [5] |

| Euroimmun Anti-SARS-CoV-2 | IgG / Spike (S1) | 190.45 | Comparable performance to other anti-S1/S2 assays [5] |

| Euroimmun Anti-SARS-CoV-2 | IgA / Spike (S1) | 45.91 | Lower DOR, indicating IgA performs least effectively in this context [5] |

| Serology (IgM) vs PCR for M. pneumoniae | IgM / M. pneumoniae antigen | Not Applicable | 90% (9/10) detection in confirmed cases vs 40% (4/10) for PCR in late-presenting CAP children [27] |

The data underscores that total antibody and anti-nucleocapsid IgG assays generally show superior diagnostic performance among serological tests. Furthermore, a study on Mycoplasma pneumoniae highlights a critical comparative insight: while PCR is a powerful direct tool, serology can demonstrate higher sensitivity in certain clinical scenarios, particularly during later stages of infection when the immune response is fully established but the pathogen may have been cleared from the sampled site [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of these diagnostic protocols relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Diagnostic Development

| Research Reagent | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | A thermostable enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands during PCR amplification [25]. | Core component of all PCR-based direct detection assays. |

| Pathogen-Specific Primers & Probes | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences (primers) that bind flanking the target region, and labeled probes for specific detection in qPCR [25]. | Defines the specificity of a PCR assay for a particular virus or bacterial gene. |

| Recombinant Antigen Panels | Purified pathogen-specific proteins (e.g., Spike S1, Nucleocapsid) produced recombinantly [5] [26]. | Used to coat plates in ELISA to capture specific antibodies from patient serum. |

| Enzyme-Conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Antibodies targeting human immunoglobulins (e.g., Anti-human IgG-HRP) for signal amplification in ELISA [28]. | Detects the presence of patient antibodies bound to the antigen in serological assays. |

| Host Response mRNA Signature Panels | Pre-defined sets of host mRNA transcripts (e.g., IRF-9, ITGAM) whose expression changes in response to infection [29]. | Used in novel host-response PCR assays to differentiate infectious from non-infectious etiologies. |

The choice between direct and indirect diagnostic methods is not a matter of superiority, but of context. A comprehensive diagnostic strategy often integrates both approaches to leverage their complementary strengths, as illustrated in the workflow below.

In conclusion, direct PCR-based methods are indispensable for confirming active infection, enabling rapid treatment, and controlling transmission through their high specificity. Indirect serological methods are crucial for understanding the epidemiology of a disease, assessing immune status, and diagnosing infections where the pathogen itself is elusive. The ongoing development of novel host-response biomarkers [29] and improved recombinant antigens [26] promises to further enhance the accuracy and utility of both paradigms. For researchers and clinicians, a nuanced understanding of the principles, protocols, and performance data of both direct and indirect diagnostics is fundamental to advancing clinical virology and improving patient outcomes.

From Bench to Bedside: Application-Specific Methodologies in Research and Clinical Practice

Application Note: Advancing Molecular Diagnostics and Surveillance

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) remains the cornerstone of modern molecular diagnostics and public health surveillance. Recent advancements have solidified its role in detecting pathogens, quantifying viral loads with precision, and tracking outbreaks in near real-time. The integration of novel buffer systems, digital quantification technologies, and portable platforms is transforming how researchers and clinicians approach infectious disease management.

Advanced Molecular Detection (AMD) represents a powerful integration of next-generation sequencing, bioinformatics, and epidemiological data to drive public health action [30]. This approach is particularly valuable for monitoring pathogen evolution at the human-animal interface, enabling early detection of spillover events and emerging variants [31]. The implementation of software containerization for bioinformatic tools has further enhanced the reproducibility and standardization of genomic workflows across public health laboratories, a critical development during multi-pathogen surveillance periods [30].

For field deployment and outbreak settings, direct PCR methodologies utilizing novel viral-inactivating transport media like DNA/RNA Defend Pro (DRDP) buffer enable rapid, extraction-free testing while maintaining biosafety [32]. This approach simplifies workflows and reduces turnaround times, which is crucial for containing outbreaks of pathogens with high transmission potential.

Table 1: Key PCR Technologies in Modern Infectious Disease Management

| Technology | Primary Application | Key Advantage | Recent Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Viral load quantification, low-abundance target detection | Absolute quantification without standard curves, high precision | Superior accuracy for high viral loads of influenza A/B and SARS-CoV-2 [33] |

| Direct PCR | Rapid field-based diagnostics, outbreak response | Omits nucleic acid extraction, uses viral-inactivating buffers | DRDP buffer enables extraction-free PCR while maintaining biosafety [32] |

| Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Pathogen genomics, outbreak tracing, variant surveillance | Comprehensive genetic characterization of pathogens | Optimized multisegment RT-PCR with dual barcoding for high-throughput sequencing [31] |

| Real-Time RT-PCR (qPCR) | Routine diagnostics, broad pathogen detection | Established gold standard, high throughput | Commercial multiplex panels for simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory pathogens [33] |

Experimental Protocol: Direct PCR for Rapid Pathogen Detection in Field Settings

Background and Principles

This protocol describes a streamlined methodology for direct PCR detection of viral pathogens using the DNA/RNA Defend Pro (DRDP) buffer system, which inactivates pathogens upon contact and stabilizes nucleic acids for extraction-free amplification [32]. This approach is particularly valuable for rapid diagnosis during outbreaks of vesiculopustular diseases like mpox, which can resemble herpesviruses (HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV) but require different containment strategies [32].

Materials and Equipment

- Transport Media: DNA/RNA Defend Pro (DRDP) buffer and Universal Transport Medium (UTM) for comparison

- Viral Stocks: HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV from clinical samples or cultured stocks

- PCR Reagents: Primers and probes specific for target pathogens, PCR master mix

- Equipment: Thermal cycler with real-time detection capability (e.g., Roche LightCycler 480 II)

- Safety Equipment: Biosafety cabinet for initial sample handling

- Consumables: Microcentrifuge tubes, PCR plates, pipette tips

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation and Inactivation

- Prepare Serial Dilutions: Create 10-fold serial dilutions (100 to 10-4) of viral stocks in both DRDP buffer and standard UTM [32].

- Safety Note: Samples in DRDP buffer are rendered non-infectious immediately upon contact. UTM samples remain infectious and must be handled in a biosafety cabinet with appropriate precautions [32].

- No Extraction Required: Proceed directly to PCR setup for DRDP samples. For UTM controls, perform thermal lysis at 95°C for 15 minutes followed by a 3-fold dilution to mitigate PCR inhibition [32].

PCR Setup and Thermal Cycling

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare 20 μL PCR reactions containing:

- 15-25% (v/v) of the clinical sample in DRDP buffer

- Primer and probe mixes specific for target pathogens

- PCR master mix

- Magnesium Optimization: For reactions exceeding 25% DRDP content, supplement with 10 mM MgCl₂ to counteract EDTA chelation in the buffer [32].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 55°C for 30 seconds with fluorescence acquisition

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Cycle Quantification (Cq) Analysis: Compare Cq values between DRDP and UTM samples across dilution series.

- Sensitivity Assessment: Determine the limit of detection for each target in both media.

- Inhibition Check: Verify that internal controls amplify efficiently in all reactions.

Diagram 1: Direct PCR workflow for rapid pathogen detection. The process eliminates nucleic acid extraction, significantly reducing processing time while maintaining biosafety through viral inactivation [32].

Expected Results and Performance Characteristics

When optimally implemented, direct PCR with DRDP buffer demonstrates equivalent or superior sensitivity compared to standard UTM processing, with Cq values favoring DRDP at higher viral loads [32]. The method maintains reliable PCR compatibility at reaction volumes containing up to 25% buffer, with magnesium supplementation effectively reversing inhibition at higher concentrations.

Application Note: Digital PCR for Precision Viral Load Quantification

The Evolution of Quantitative PCR

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a significant advancement in nucleic acid quantification, partitioning samples into thousands of individual reactions to enable absolute quantification without standard curves [33]. This technology has transitioned from a specialized research tool to a clinically relevant platform, particularly valuable for applications requiring high sensitivity and precision [34] [35].

During the 2023-2024 "tripledemic" involving influenza A, influenza B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2, dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads of RSV compared to Real-Time RT-PCR [33]. This precision is crucial for understanding infection dynamics, treatment efficacy, and transmission risk.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 2: Performance Comparison of dPCR vs. Real-Time RT-PCR in Respiratory Virus Detection

| Performance Metric | Digital PCR (dPCR) | Real-Time RT-PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Absolute quantification without standard curves [33] [35] | Relative quantification requiring standard curves [33] |

| Precision at High Viral Loads | Superior accuracy for influenza A, influenza B, SARS-CoV-2 [33] | Lower precision compared to dPCR [33] |

| Sensitivity for Low Viral Loads | Enhanced detection of low-abundance targets [35] | May miss low viral loads in positive patients [35] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | High tolerance to PCR inhibitors [35] | Sensitive to inhibitors in complex matrices [33] |

| Throughput and Cost | Lower throughput, higher cost per sample [33] | High throughput, established cost structure [33] |

| Clinical Utility | Monitoring treatment response, resolving equivocal results [35] | Broad screening, routine diagnostics [33] |

Experimental Protocol: Absolute Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load Using Digital PCR

Background and Principles

This protocol details the application of droplet digital PCR (dPCR) for absolute quantification of SARS-CoV-2 viral load in clinical specimens, enabling precise monitoring of infection dynamics and treatment response [35]. The method specifically targets the N (nucleocapsid) and ORF1ab (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) genes of SARS-CoV-2, which are highly conserved and abundant in the viral genome [35].

Materials and Equipment

- Clinical Specimens: Nasopharyngeal swabs collected in viral transport media

- RNA Extraction Kit: Compatible with KingFisher or similar automated systems

- dPCR System: QIAcuity or equivalent nanowell-based platform [33]

- SARS-CoV-2 Assay: Primers and probes targeting N and ORF1ab genes

- Internal Control: Human or exogenous control to monitor extraction and amplification efficiency

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Processing and RNA Extraction

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract RNA from 200 μL of clinical sample using automated systems (e.g., KingFisher Apex) with viral RNA extraction kits following manufacturer protocols [33].

- Quality Assessment: Verify RNA integrity and concentration using spectrophotometric or fluorometric methods.

- Aliquot Storage: Divide extracted RNA into aliquots for parallel testing by dPCR and RT-qPCR if comparative analysis is planned.

dPCR Reaction Setup

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare dPCR reactions according to platform-specific requirements, typically including:

- 1X dPCR master mix

- Primers and probes for SARS-CoV-2 targets (N and ORF1ab)

- Internal control assay

- 2-5 μL of extracted RNA template

- Partitioning: Load reactions into appropriate cartridges or chips for partition generation following manufacturer instructions.

- Sealing and Loading: Ensure proper sealing of partitions before thermal cycling.

Thermal Cycling and Data Analysis

- Amplification Protocol: Perform PCR amplification with platform-optimized cycling conditions:

- Reverse transcription: 50°C for 10-30 minutes

- Enzyme activation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes

- 40-45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 55-60°C for 30-60 seconds

- Endpoint Reading: Following amplification, analyze each partition for fluorescence signal to determine positive and negative reactions.

- Poisson Statistical Analysis: Apply Poisson statistics to calculate absolute copy numbers of target genes in the original sample, correcting for partition volume and dilution factors [35].

Diagram 2: Digital PCR workflow for absolute viral load quantification. The partitioning enables precise counting of target molecules through Poisson statistical analysis, eliminating the need for standard curves [33] [35].

Expected Results and Interpretation

dPCR typically demonstrates enhanced sensitivity compared to RT-qPCR, particularly for samples with low viral loads or those requiring precise quantification [35]. The method provides absolute quantification of viral load, enabling more accurate monitoring of treatment response and disease progression. When applied to serial samples from hospitalized patients, dPCR can track viral load changes with greater precision than RT-qPCR, offering valuable insights into viral persistence and clearance dynamics [35].

Application Note: Genomic Surveillance and Public Health Implementation

Pathogen Genomics in Public Health

The integration of pathogen genomics into public health surveillance represents a transformative advancement for outbreak investigation and antimicrobial resistance monitoring. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies enable high-resolution strain typing and transmission tracking, providing insights that inform targeted public health interventions [30].

The Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative (NGSQI) addresses laboratory challenges by developing tools and resources for robust quality management systems, helping laboratories navigate complex regulatory environments while implementing NGS effectively [30]. This standardization is critical for ensuring data comparability across public health networks.

Implementation Case Study: Washington State

The Washington State Department of Health successfully piloted a genomic surveillance approach for multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) using whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and a genomics-first cluster definition [30]. This methodology identified six distinct carbapenemase-producing organism outbreaks across three species: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Klebsiella pneumoniae [30].

The integration of genomic and epidemiologic data proved highly congruent, enabling public health officials to refine linkage hypotheses and address surveillance gaps [30]. This approach demonstrates how genomic data can modernize communicable disease surveillance and enhance outbreak detection precision.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced PCR Applications

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Defend Pro (DRDP) Buffer | Viral inactivation and nucleic acid stabilization for direct PCR | Enables extraction-free PCR; contains EDTA requiring magnesium supplementation at high concentrations [32] |

| QIAcuity dPCR System | Nanowell-based digital PCR platform | Partitions samples into ~26,000 reactions; compatible with high-throughput processing [33] |

| LunaScript RT Master Mix | Reverse transcription for whole-genome amplification | Used in optimized influenza WGS protocols with modified cycling conditions [31] |

| Multiplex Primer Panels (Allplex) | Simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory pathogens | Commercial panels for influenza A/B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2 used in tripledemic surveillance [33] |

| Oxford Nanopore Sequencing | Portable, real-time long-read sequencing | Enables rapid genomic surveillance with dual barcoding for high-throughput multiplexing [31] |

| MBTuni Primers | Whole-genome amplification of influenza A virus | Universal primers targeting conserved regions for comprehensive genome coverage [31] |

The evolution of PCR technologies continues to reshape the landscape of infectious disease diagnostics and surveillance. Emerging trends point toward greater integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning for data analysis, interpretation, and predictive modeling [36]. The development of point-of-care QUICK-PCR systems—quick, ubiquitous, integrated, and cost-efficient—represents a promising direction for decentralized testing and rapid pandemic response [37].

The convergence of dPCR with next-generation sequencing creates powerful hybrid workflows that combine precise quantification with comprehensive genetic characterization [34]. These integrated approaches will enhance our ability to detect emerging variants, monitor treatment efficacy, and implement timely public health interventions.

As these technologies mature and become more accessible, they promise to reduce healthcare inequalities by bringing advanced diagnostic capabilities to resource-limited settings. The ongoing standardization of methods and quality control frameworks will ensure that these powerful tools deliver reliable, actionable data for researchers, clinicians, and public health professionals worldwide.

Serology, the study of antibodies in serum, remains a cornerstone of clinical virology, providing critical insights into individual and population-level immune responses. These techniques are indispensable for determining immune status following infection or vaccination, conducting seroprevalence studies to understand disease penetration within communities, and monitoring the effectiveness of vaccine campaigns. While molecular methods like PCR excel at detecting active infections, serological assays offer the unique ability to retrospectively identify past infections and quantify established immunity through antibody detection [38] [39]. This application note details standardized protocols and contemporary data illustrating these three fundamental applications of serological testing in virology.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the vital importance of robust serological monitoring, particularly for informing booster vaccination strategies. A 2025 study demonstrated that providing healthcare workers with their neutralizing antibody status influenced vaccination decisions, with over two-thirds (68.1%) indicating that results would affect their choice to receive a booster dose [40]. This "test-and-boost" approach represents a practical application of immune status determination in public health policy.

Application Note 1: Immune Status Determination

Principle and Significance

Determining immune status involves detecting pathogen-specific antibodies to assess an individual's immunological history and current protection level. The presence of Immunoglobulin G (IgG) typically indicates past infection or vaccination, while Immunoglobulin M (IgM) often suggests recent exposure. Quantitative serology measures antibody titers, providing a correlate of protection against specific pathogens [38]. This application is particularly valuable for managing healthcare workers, immunocompromised patients, and for epidemiological surveillance.

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Table 1: Common Serological Techniques for Immune Status Determination

| Technique | Target | Principle | Time to Result | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | Viral antigens or antibodies | Enzyme-conjugated antibodies produce colorimetric signal | 2-5 hours | High-throughput screening, quantitative antibody measurement |

| Hemagglutination Inhibition (HAI) Assay | Influenza-specific antibodies | Antibodies prevent viral hemagglutination of red blood cells | 4-6 hours | Influenza immunity status, vaccine response evaluation |

| Virus Neutralization Assay (VN) | Neutralizing antibodies | Serum antibodies prevent viral infection of cell cultures | 3-7 days | Gold standard for protective immunity, highly specific |

| Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA) | Viral antigens | Fluorescently-labeled antibodies detect bound serum antibodies | 3-4 hours | Autoimmune testing, confirmatory testing |

| Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) | Viral antibodies or antigens | Lateral flow immunochromatography | 10-30 minutes | Point-of-care testing, quick screening |

Detailed Protocol: Virus Neutralization Assay for SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies

Principle: This protocol evaluates serum neutralizing capacity by measuring its ability to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection of susceptible cells in vitro, providing a functional assessment of protective immunity [40].

Materials:

- Vero E6 cells (ATCC CRL-1586)

- SARS-CoV-2 virus isolate (appropriate biosafety level required)

- DMEM culture medium with 2% fetal bovine serum

- 96-well tissue culture plates

- Patient serum samples (heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 minutes)

- Positive and negative control sera

- Fixation solution (4% formaldehyde)

- Staining solution (crystal violet)

Procedure:

- Seed Vero E6 cells in 96-well plates at 2×10⁴ cells/well and incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ until 90% confluent.

- Prepare two-fold serial dilutions of heat-inactivated serum samples in culture medium (starting from 1:8 to 1:1024).

- Mix equal volumes of each serum dilution with 100 TCID₅₀ of SARS-CoV-2 virus and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour.

- Remove growth medium from cell plates and add 100μL of serum-virus mixture to appropriate wells.

- Include virus control wells (virus without serum), cell control wells (medium only), and serum toxicity controls (serum without virus).

- Incubate plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 72 hours.

- Fix cells with 4% formaldehyde for 30 minutes, then stain with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 minutes.

- Wash plates gently with water and air dry.

- The neutralization titer is the highest serum dilution that prevents cytopathic effect in ≥50% of wells.

Interpretation: A neutralizing antibody titer ≥1:32 is considered indicative of protective immunity against SARS-CoV-2, though clinical correlates may vary by variant [40].

Application Note 2: Seroprevalence Studies

Principle and Significance

Seroprevalence studies measure the proportion of a population with specific antibodies against a pathogen, providing crucial data on cumulative infection rates and population immunity levels. These studies help identify the extent of undetected infections, monitor transmission dynamics, and guide public health interventions. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of serial serosurveys for tracking epidemic progression and the impact of control measures [40].

Recent Data and Findings

Table 2: COVID-19 Seroprevalence Study Among Primary Healthcare Workers (2025)

| Parameter | Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Study Population | 474 healthcare workers | Multidisciplinary staff with high exposure risk |

| Neutralizing Antibody Seroprevalence | 99.2% | Near-universal seropositivity in vaccinated cohort |

| Previous COVID-19 Infection | 80.6% | High infection rate despite vaccination |

| Median Time to Infection Post-Vaccination | 163 days | Evidence of waning immunity |

| Preferred Testing Method | 77.0% preferred finger prick | Importance of acceptable sampling methods |

| Influence on Booster Decision | 68.1% | Serological testing impacts vaccination behavior |

This 2025 study demonstrated remarkably high seroprevalence (99.2%) of COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies among fully vaccinated primary care staff, with most participants (79.7%) contracting COVID-19 after vaccination at a median time of 163 days post-vaccination [40]. These findings underscore the value of seroprevalence monitoring in high-risk groups and the necessity for timely boosters.

Detailed Protocol: Population-Level Serosurvey Design

Study Design Considerations:

- Sampling Strategy: Implement stratified random sampling to ensure population representation across age, geographic, and demographic groups.

- Sample Size Calculation: For seroprevalence studies, sample size is typically calculated based on an estimated seroprevalence of 50% (which provides the largest sample size required), with a precision of 5% and 95% confidence interval, yielding a minimum sample of 385 participants [40].

- Ethical Considerations: Obtain institutional review board approval and individual informed consent.

- Data Collection: Standardized questionnaires should capture demographic data, clinical history, vaccination status, and prior infection history.

Laboratory Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect serum, plasma, or capillary blood samples. For point-of-care testing, finger prick blood collection increases acceptability [40].

- Testing Algorithm: Employ a two-test algorithm for high accuracy—initial screening by ELISA or rapid test, with positive samples confirmed by a different method (e.g., virus neutralization).

- Quality Control: Include standard reference sera in each assay run to ensure inter-assay comparability.

- Data Analysis: Calculate seroprevalence as the proportion of positive samples with 95% confidence intervals, adjusting for test performance characteristics and sampling design.

Application Note 3: Vaccine Efficacy Monitoring

Principle and Significance

Serological methods are essential for evaluating vaccine immunogenicity and monitoring effectiveness in real-world settings. While randomized controlled trials establish initial efficacy, ongoing serological monitoring detects waning immunity and assesses protection against emerging variants. Vaccine effectiveness (VE) is calculated by comparing disease incidence between vaccinated and unvaccinated populations, with serological correlates providing mechanistic insights [41] [42].

Recent Vaccine Effectiveness Data

Table 3: 2024-2025 COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness Estimates

| Outcome | Population | Effectiveness (%) | Time Frame | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED/UC Visits | Adults ≥18 years | 33% (95% CI: 28-38) | 7-119 days post-vaccination | VISION Network [41] |

| Hospitalization | Immunocompetent adults ≥65 years | 45-46% | 7-119 days post-vaccination | VISION/IVY Networks [41] |

| Hospitalization | Immunocompromised adults ≥65 years | 40% (95% CI: 21-54) | 7-119 days post-vaccination | VISION Network [41] |

| Infection | Adults | 44.7% | 4 weeks post-vaccination | UNC Study [42] |

| Hospitalization/Death | Adults | 57.5% | 4 weeks post-vaccination | UNC Study [42] |

Recent data from the 2024-2025 respiratory season demonstrates that updated COVID-19 vaccines continue to provide substantial protection against severe outcomes, though effectiveness wanes over time. Vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization was 57.5% at 4 weeks post-vaccination but declined to 34.0% by 20 weeks [42]. These findings highlight the importance of serological monitoring to optimize booster timing, particularly for high-risk populations.

Detailed Protocol: Vaccine Effectiveness Study Using Test-Negative Design

Principle: The test-negative design is an efficient method for monitoring vaccine effectiveness in real-world settings by comparing vaccination status between cases (test-positive) and controls (test-negative) with similar healthcare-seeking behavior [41].

Materials and Data Sources:

- Electronic health records from participating healthcare facilities

- State vaccination registries

- Laboratory test results for SARS-CoV-2

- Trained personnel for data abstraction

- Statistical software (e.g., R, SAS, GraphPad Prism)

Procedure:

- Case Ascertainment: Identify patients with COVID-19-like illness who received molecular (RT-PCR) or antigen testing for SARS-CoV-2 within 10 days before or 72 hours after an eligible healthcare encounter.

- Case Definition: Case-patients test positive for SARS-CoV-2; control patients test negative.

- Vaccination Status: Determine 2024-2025 COVID-19 vaccination status from state registries, EHRs, and/or medical claims. Consider patients vaccinated if they received the vaccine ≥7 days before the index date.

- Exclusion Criteria:

- Patients vaccinated <7 days or ≥120 days before the encounter

- Those receiving a 2024-2025 dose <2 months after a previous COVID-19 vaccine

- Immunocompetent persons receiving more than one 2024-2025 dose

- Patients co-infected with influenza or RSV

- Statistical Analysis:

- Use multivariable logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (OR) for vaccination comparing cases to controls