Molecular Mechanisms of Viral Pathogenesis: From Viral Entry to Host Response and Therapeutic Intervention

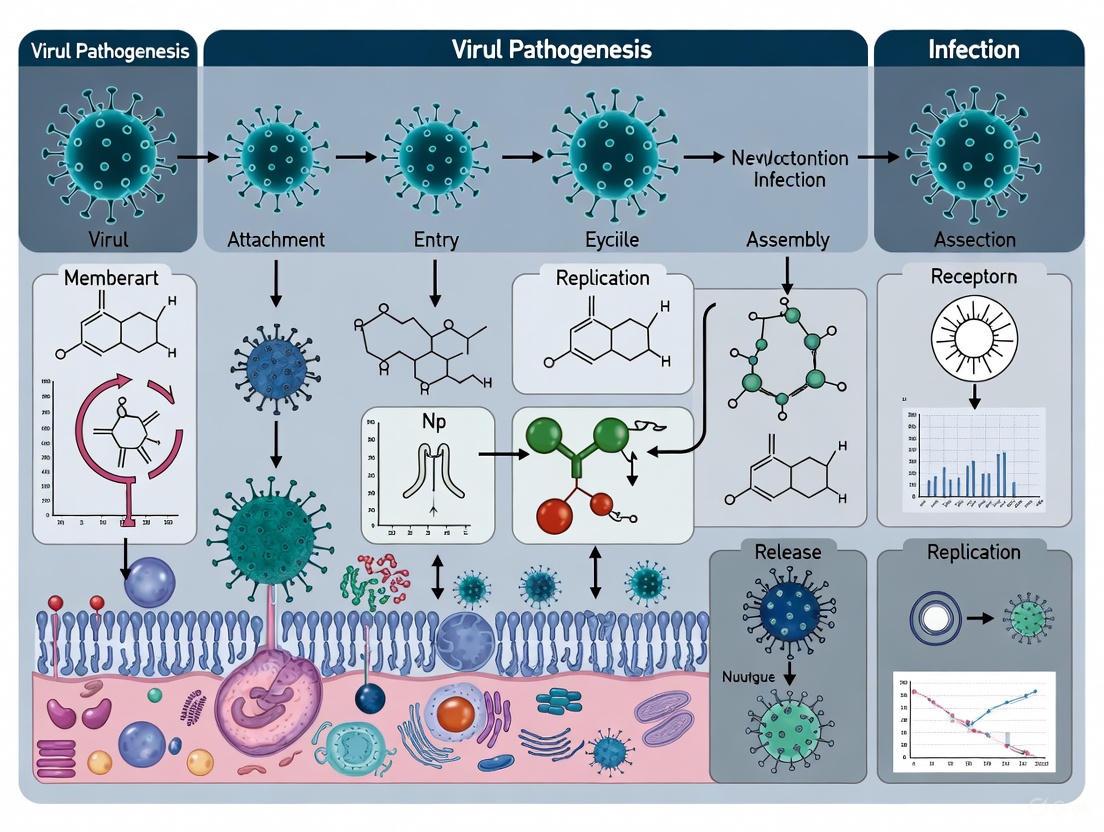

This comprehensive review explores the intricate molecular mechanisms of viral pathogenesis and infection, synthesizing foundational concepts with cutting-edge research and methodological advances.

Molecular Mechanisms of Viral Pathogenesis: From Viral Entry to Host Response and Therapeutic Intervention

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the intricate molecular mechanisms of viral pathogenesis and infection, synthesizing foundational concepts with cutting-edge research and methodological advances. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article examines viral entry strategies, host-pathogen interactions, immune evasion tactics, and metabolic reprogramming. It critically evaluates contemporary research methodologies, computational approaches, and model systems driving the field forward. The analysis extends to troubleshooting experimental challenges and optimizing therapeutic strategies, while providing validation through comparative analysis of pathogenesis across virus families. By integrating foundational knowledge with translational applications, this review serves as a strategic resource for advancing antiviral drug discovery and novel therapeutic development.

Decoding Viral Invasion: Molecular Entry Portals and Early Host-Pathogen Dynamics

Viral entry into host cells represents the critical first step in infection and a major determinant of pathogenic mechanisms. This process initiates when viral particles attach to specific receptor molecules on the host cell surface, leading to internalization and delivery of the viral genome into the cellular replication machinery [1] [2]. The presence and distribution of these receptor molecules largely dictate viral tropism—the specific tissues and species a virus can infect—making receptor identification fundamental to understanding viral pathogenesis and developing targeted therapeutic interventions [2]. Viruses have evolved to exploit a diverse array of cell surface components as entry receptors, including proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, with recognition mediated by specialized viral attachment proteins (VAPs) that exhibit precise molecular complementarity to their cognate receptors [3] [1].

The strategic importance of viral entry receptors extends beyond merely anchoring the virus to the cell surface. Receptor binding often triggers essential conformational changes in viral entry proteins that drive subsequent entry steps, including membrane fusion for enveloped viruses or penetration for non-enveloped viruses [4] [1]. Furthermore, some viruses have developed the capacity to utilize multiple receptors either simultaneously or sequentially, engaging initial attachment factors that concentrate virions on the cell surface before transferring to primary entry receptors that mediate internalization [3]. This complex receptor utilization strategy enhances infection efficiency and expands cellular tropism, contributing significantly to the pathogenic potential of many viruses. Consequently, mapping the intricate interplay between viruses and their cellular receptors provides crucial insights into disease mechanisms and reveals vulnerable points in the viral life cycle that can be targeted therapeutically.

Fundamental Principles of Viral Receptor Interactions

Defining Viral Receptors and Attachment Factors

A precise distinction exists between viral attachment factors and true entry receptors, though both participate in the initial stages of cell recognition. Attachment factors are cell surface molecules that promote virus binding but do not directly mediate genome internalization; they function primarily to concentrate virions on the cell surface, thereby facilitating subsequent interactions with bona fide entry receptors [3] [1]. In contrast, entry receptors not only bind viruses with high specificity but also actively promote downstream entry processes such as internalization or conformational activation of viral fusion machinery [3]. For instance, while heparan sulfate proteoglycans often serve as attachment factors for various viruses, proteins like ACE2 for SARS-CoV-2 and CD4 for HIV-1 function as genuine entry receptors by triggering essential structural rearrangements required for membrane fusion and genome delivery [5] [1].

The molecular interactions between viruses and their receptors exhibit several conserved features that optimize infection efficiency. First, viral attachment proteins (VAPs) typically engage receptors through moderate-affinity interactions (0.1–1 μM range for monomeric binding) that, when multiplied across multiple binding sites on a single virion, result in extremely high overall avidity [1]. Second, receptor binding sites on viruses frequently reside within depressed surface regions or "canyons" that may help shield critical interaction motifs from host immune surveillance while still permitting access to receptor molecules [4] [1]. Third, many viruses exploit receptors that perform essential physiological functions and are therefore constitutively expressed on susceptible cell types, ensuring consistent availability for viral exploitation [6]. These strategic interaction principles enable viruses to maintain a delicate balance between entry efficiency and evasion of host defenses.

Structural Basis of Receptor Recognition

Structural studies have revealed remarkable diversity in how viral proteins recognize and bind to their cellular receptors. The spike proteins of coronaviruses, for instance, contain two distinct domains within their S1 subunit—the N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and C-terminal domain (S1-CTD)—either or both of which can function as receptor-binding domains (RBDs) [6]. This structural arrangement allows different coronaviruses to recognize varied receptors despite sharing overall architectural similarities. For example, while SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63 both utilize the S1-CTD to bind ACE2, they belong to different genera (β and α, respectively), whereas MERS-CoV, also a β-coronavirus, uses its S1-CTD to bind an entirely different receptor, DPP4 [6].

The receptor recognition process often involves dramatic conformational transitions in viral proteins that are triggered by specific cellular cues. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein exists in dynamic equilibrium between "closed" and "open" states, with the open state exposing the receptor-binding motif for ACE2 interaction [7]. Notably, emerging variants of concern like Omicron show a shifted equilibrium toward the open conformation, enhancing receptor accessibility and contributing to increased transmissibility [7]. Similarly, enveloped viruses such as influenza and HIV possess fusion glycoproteins that undergo extensive structural rearrangements from metastable pre-fusion states to stable post-fusion configurations, a process typically initiated by receptor binding and/or subsequent environmental triggers like low pH [4] [7]. These structural insights not only elucidate fundamental entry mechanisms but also inform the design of inhibitors targeting specific conformational states.

Table 1: Classification of Major Viral Entry Receptors with Representative Examples

| Receptor Type | Molecular Characteristics | Representative Viruses | Cellular Function of Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| IgSF Proteins | Immunoglobulin-like domains | Poliovirus, Rhinovirus, Coxsackievirus | Cell adhesion (ICAM-1, CAR) |

| Enzymes | Metalloproteases, exoproteases | SARS-CoV-2 (ACE2), MERS-CoV (DPP4), HCoV-229E (APN) | Peptide hormone processing, blood pressure regulation |

| Carbohydrates | Sialic acid derivatives | Influenza virus, Coronavirus OC43, Coronavirus HKU1 | Cell surface glycosylation patterns |

| Lipids | Cholesterol, phospholipids | SV40, Rotavirus | Membrane structure components |

| Integrins | Heterodimeric adhesion receptors | Foot-and-mouth disease virus, Echovirus 1 | Cell-matrix adhesion, signaling |

Methodologies for Receptor Identification and Validation

Genetic and Proteomic Approaches

Modern receptor identification relies heavily on genetic screening methods that systematically evaluate gene function across the cellular genome. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has emerged as a particularly powerful tool for this purpose, enabling researchers to generate comprehensive knockout libraries where individual genes are inactivated across cell populations [8]. When subjected to viral challenge, cells lacking essential entry receptors survive while susceptible cells perish, allowing subsequent sequencing to identify the protective genetic modifications. This approach was successfully employed to identify the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) family members LRP1, LRP4, and VLDLR as entry receptors for yellow fever virus, and LRP8 for tick-borne encephalitis virus [8]. The experimental protocol typically involves: (1) generating a CRISPR knockout library in susceptible target cells; (2) infecting cells with the virus of interest at appropriate multiplicity of infection; (3) recovering surviving cells after sufficient time for virus-induced cytopathy; (4) amplifying and sequencing the guide RNAs from surviving cells; and (5) validating candidate genes through individual knockout studies.

Complementing genetic approaches, quantitative proteomics enables systematic mapping of protein-protein interactions during viral entry [3]. Advanced mass spectrometry techniques now allow sensitive detection and quantitation of proteins from limited biological material, making it possible to identify virus-associated host proteins with high confidence. A typical workflow involves: (1) incubating viral particles or viral envelope proteins with cell lysates or membrane preparations; (2) capturing virus-host protein complexes using antibodies against viral proteins; (3) digesting captured proteins into peptides and analyzing by high-resolution mass spectrometry; (4) comparing protein abundances between experimental and control samples to identify specifically bound host proteins; and (5) constructing interaction networks to distinguish primary receptors from secondary binding partners [3]. This approach proved valuable in identifying the complex network of proteins that mediate hepatitis C virus entry, including CD81, SR-BI, claudin-1, and occludin [3].

Functional Validation Strategies

Candidate receptors identified through genetic or proteomic screens require rigorous functional validation to establish their necessity and sufficiency for viral entry. The gold standard validation protocol involves a series of complementary experiments that collectively demonstrate receptor function [8] [1]. First, gene knockout or knockdown experiments determine whether removing the candidate receptor from previously susceptible cells confers resistance to infection. This can be achieved through CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene disruption, RNA interference, or antibody blockade [8]. Second, heterologous expression studies test whether introducing the candidate receptor into non-susceptible cells renders them permissive to infection, effectively converting them into targets for viral entry [8] [6]. For the yellow fever virus receptors, researchers demonstrated that genetically eliminating LDLR family members from cell surfaces blocked infection, while adding abnormally high numbers of these receptors allowed increased viral entry [8].

Additional validation steps include assessing the direct binding between viral attachment proteins and candidate receptors using techniques like surface plasmon resonance, isothermal titration calorimetry, or co-immunoprecipitation [6] [1]. Furthermore, structural studies of virus-receptor complexes provide the highest resolution evidence for specific molecular interactions, as exemplified by crystal structures of coronavirus spike protein domains complexed with their cognate receptors ACE2, DPP4, or APN [6]. These structural insights not only confirm receptor identity but also reveal the atomic details of binding interfaces, informing the design of targeted entry inhibitors. Together, this multi-faceted validation framework ensures that identified molecules genuinely function as entry receptors rather than merely participating in downstream post-entry processes.

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for viral receptor identification and validation, progressing from initial screening through functional validation to mechanistic characterization.

Diverse Viral Entry Pathways and Mechanisms

Endocytic Mechanisms of Viral Entry

Viruses exploit multiple cellular endocytic pathways to gain entry into host cells, with the specific route determined by virus size, structure, and receptor interactions. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis represents the most well-characterized entry pathway, utilized by both enveloped viruses like influenza and non-enveloped viruses like adenovirus [4] [7]. This process initiates when virus binding to surface receptors triggers recruitment of clathrin proteins to the intracellular membrane face, forming characteristic coated pits that invaginate and pinch off to form virus-containing endosomes [7]. As these endosomal vesicles undergo maturation, they experience a progressive decrease in internal pH, which serves as a critical trigger for conformational changes in viral proteins that facilitate membrane penetration or fusion [4]. The experimental protocol for studying clathrin-dependent entry typically involves: (1) treating cells with pharmacological inhibitors of clathrin function such as chlorpromazine or pitstop; (2) knocking down essential clathrin pathway components using siRNA; (3) visualizing virus co-localization with clathrin light chain using fluorescence microscopy; and (4) monitoring infection kinetics when endosomal acidification is blocked using agents like bafilomycin A1 or ammonium chloride.

Alternative entry pathways provide viruses with additional options for cell invasion. Caveolar entry is preferentially used by certain non-enveloped viruses like SV40 and involves cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains that form distinctive flask-shaped invaginations [4] [7]. Unlike clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolar entry maintains a neutral pH environment throughout internalization, delivering viruses to specialized organelles called caveosomes rather than acidic endosomes [7]. Macropinocytosis represents a third major entry mechanism, employed by viruses such as vaccinia virus and Ebola virus, involving actin-mediated ruffling of the plasma membrane that engulfs virions in large fluid-filled vesicles [7]. This pathway is typically studied using inhibitors of actin polymerization (cytochalasin D), Na+/H+ exchangers (EIPA), or Rac1 signaling. The diversity of entry pathways highlights viral adaptability, with some viruses like SARS-CoV-2 capable of utilizing multiple routes—either direct fusion at the plasma membrane when TMPRSS2 is present or endosomal entry via cathepsin L activation when TMPRSS2 is limited [7].

Membrane Fusion and Penetration Strategies

Following cellular internalization, viruses must breach intracellular membranes to release their genetic material into the replication-competent compartments of the cell. Enveloped viruses accomplish this through membrane fusion, a process mediated by specialized viral fusion proteins that undergo dramatic conformational changes to merge the viral envelope with cellular membranes [4] [7]. These fusion proteins exist in metastable pre-fusion configurations that, when triggered by receptor binding or low pH, refold into extremely stable post-fusion states, releasing substantial free energy that drives membrane merger [7]. Class I fusion proteins (e.g., influenza HA, HIV Env) typically feature central α-helical coiled-coils that thrust the fusion peptide toward the target membrane, while class II fusion proteins (e.g., flavivirus E, alphavirus E1) rearrange from dimeric to trimeric states with fusion loops positioned for membrane insertion [4]. The experimental analysis of viral fusion typically employs: (1) liposome-based fusion assays with fluorescence dequenching; (2) cell-cell fusion assays measuring reporter gene activation; (3) structural studies of pre- and post-fusion conformations; and (4) site-directed mutagenesis of key hydrophobic fusion peptides.

Non-enveloped viruses face the particular challenge of penetrating cellular membranes without the advantage of a lipid envelope, instead employing specialized protein components that disrupt membrane integrity. Some non-enveloped viruses, such as poliovirus, undergo receptor-induced conformational changes that expose hydrophobic domains or myristoyl groups capable of inserting into and disrupting target membranes [4] [1]. Others, including adenoviruses, utilize membrane-lytic peptides that are exposed following partial disassembly of the viral capsid in the endosomal compartment, creating pores through which the viral genome can enter the cytoplasm [1]. The penetration mechanisms of non-enveloped viruses share similarities with those employed by certain protein toxins, such as anthrax toxin, which also form oligomeric pores in target membranes [4]. Studying these penetration events often involves: (1) electron microscopy to visualize membrane disruptions; (2) electrophysiology to detect channel formation; (3) fluorescence assays monitoring release of encapsulated dyes from liposomes; and (4) biochemical analysis of capsid disassembly intermediates.

Table 2: Major Viral Entry Pathways with Key Characteristics and Representative Viruses

| Entry Pathway | Key Features | Cellular Components | Representative Viruses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis | Receptor-mediated, forms coated vesicles, low pH trigger | Clathrin, dynamin, AP2 adaptors | Influenza virus, Adenovirus, Hepatitis C virus |

| Caveolar/Lipid Raft-Mediated | Cholesterol-rich domains, neutral pH, caveosomes | Caveolin-1, cholesterol, dynamin | SV40, Polyomavirus, Echovirus 1 |

| Macropinocytosis | Actin-driven, fluid-phase uptake, receptor-independent | Rac1, Pak1, actin, Na+/H+ exchangers | Vaccinia virus, Ebola virus, Coxsackievirus B |

| Direct Fusion | Plasma membrane fusion, pH-independent | Specific receptors, surface proteases | HIV-1, SARS-CoV-2 (TMPRSS2-dependent) |

| Endosomal Fusion | Acid pH-dependent, cathepsin priming | Early/late endosomes, cathepsins | SARS-CoV-2 (TMPRSS2-low), Influenza virus |

Case Studies in Receptor Utilization

Coronavirus Receptor Recognition Diversity

Coronaviruses exemplify the evolutionary ingenuity of viral receptor utilization, employing diverse entry receptors despite sharing common structural features in their spike glycoproteins. The spike proteins of coronaviruses contain two potentially receptor-binding domains—the N-terminal domain (S1-NTD) and C-terminal domain (S1-CTD)—with different coronaviruses utilizing these domains in various combinations to recognize distinct receptor molecules [6]. This strategic flexibility enables closely related coronaviruses to target different tissues and host species. For instance, SARS-CoV and HCoV-NL63, despite belonging to different genera (β and α, respectively), both utilize ACE2 as their primary receptor through interactions with the S1-CTD [6] [5]. In contrast, MERS-CoV, a β-coronavirus like SARS-CoV, targets DPP4 via its S1-CTD, while HCoV-229E, an α-coronavirus, uses aminopeptidase N (APN) as its receptor [6] [5]. This pattern demonstrates that receptor specificity does not strictly follow phylogenetic relationships, with very different coronavirus S1-CTDs from different genera sometimes recognizing the same receptor, while highly similar S1-CTDs within the same genus can recognize different receptors [6].

Structural biology has been instrumental in elucidating the molecular basis of coronavirus receptor selection. Crystal structures of coronavirus spike domains complexed with their receptors reveal both conserved and divergent strategies for receptor engagement. The SARS-CoV spike protein binds ACE2 through an extended loop that forms a gently concave surface with two ridges, termed the receptor-binding motif (RBM), which makes all contacts with the N-terminal lobe of ACE2 away from its enzymatic active site [6]. Similarly, the MERS-CoV spike engages DPP4 through extensive interactions that also avoid interference with the receptor's enzymatic function [6]. Beyond protein receptors, some coronaviruses utilize carbohydrate receptors, with β-coronaviruses OC43 and HKU1 recognizing 9-O-acetylated sialic acids, while α-coronavirus TGEV and γ-coronavirus IBV use sugar-based receptors recognized through their S1-NTDs [6]. This receptor diversity likely contributes to the expanded host range and tissue tropism observed across the coronavirus family, facilitating cross-species transmission and emergence of novel pathogenic strains like SARS-CoV-2.

Flavivirus Receptor Identification and Decoy Strategies

Recent research on flaviviruses has revealed unexpected insights into receptor usage and inspired innovative therapeutic approaches. Through systematic CRISPR-Cas9 screening, researchers identified members of the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) family as essential entry receptors for multiple flaviviruses [8]. Specifically, yellow fever virus was found to utilize LRP1, LRP4, and VLDLR for cellular entry, while the closely related tick-borne encephalitis virus employs LRP8 [8]. The distribution of these receptors correlates strongly with disease pathogenesis—LRP1 is highly expressed on liver cells, the primary target of yellow fever virus, while LRP8 is found primarily on nervous system cells, consistent with the neurotropism of tick-borne encephalitis virus [8]. This receptor identification followed a rigorous validation protocol: (1) genetic knockout of LDLR family members in cells rendered them resistant to infection; (2) heterologous expression of these receptors in non-susceptible cells conferred susceptibility; and (3) receptor overexpression enhanced viral entry in a dose-dependent manner.

Building on these receptor discoveries, researchers designed innovative decoy receptor molecules that effectively block viral entry [8]. These decoys consist of the extracellular domain of the identified LDLR family receptors fused to the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin, creating soluble receptor fragments that mimic the viral binding sites on cell surfaces [8]. When administered prophylactically, these decoys potently inhibited infection of human and mouse cells in vitro and protected immunodeficient mice from lethal yellow fever virus challenge [8]. The therapeutic strategy is particularly promising because it targets conserved host proteins rather than rapidly evolving viral components, potentially imposing a significant evolutionary constraint on viral escape mutants—any mutation that avoids decoy binding would likely also reduce affinity for the essential cellular receptor, thereby diminishing infectivity [8]. This decoy approach represents a paradigm shift in antiviral development, moving from direct viral targeting to host factor exploitation, with potential applications against diverse viruses sharing common receptor usage patterns.

Diagram 2: Viral entry process with key intervention points for therapeutic development, including receptor blockers, fusion inhibitors, and the novel decoy receptor strategy.

Experimental Toolkit for Viral Entry Research

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Contemporary viral entry research employs a sophisticated toolkit of reagents and technologies designed to interrogate specific stages of the entry process. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing systems have become indispensable for genetic screening, enabling comprehensive identification of host factors essential for viral entry [8]. These systems typically utilize lentiviral or retroviral delivery of guide RNA libraries targeting thousands of genes, followed by selection under viral challenge to identify protective knockouts. For proteomic analyses, affinity purification mass spectrometry relies on high-quality antibodies against viral surface proteins to capture virus-host protein complexes from cell lysates, with quantitative comparisons between infected and uninfected samples revealing specific interactions [3]. Advanced imaging techniques, particularly cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography, provide atomic-resolution views of virus-receptor interactions, as demonstrated by the structures of coronavirus spike proteins complexed with their cognate receptors [6] [1].

Functional validation of candidate receptors requires additional specialized reagents and assays. Neutralizing antibodies against putative receptors serve both as validation tools and potential therapeutic leads, blocking receptor function to assess infection inhibition [1]. Recombinant soluble receptor fragments find dual use in validation studies and therapeutic development, both as competitive inhibitors and decoy receptors [8] [6]. For studying entry kinetics and pathways, chemical inhibitors targeting specific cellular processes—such as bafilomycin A1 for endosomal acidification, chlorpromazine for clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and EIPA for macropinocytosis—help delineate the precise route of viral internalization [7]. Additionally, reporter virus systems incorporating fluorescent or luminescent markers enable real-time visualization and quantification of entry events in live cells, providing dynamic information about the spatial and temporal progression of infection. Together, this comprehensive experimental toolkit allows researchers to dissect the complex molecular choreography of viral entry with increasing precision.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Entry Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Systems | CRISPR-Cas9 libraries, RNAi reagents | Genome-wide knockout screens, candidate validation | Off-target effects, delivery efficiency, knockout completeness |

| Proteomic Tools | Co-immunoprecipitation antibodies, crosslinkers, mass spectrometry | Virus-host protein interaction mapping, complex identification | Antibody specificity, interaction stability, false positive rates |

| Structural Biology | Cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography, surface plasmon resonance | Atomic-level receptor binding analysis, conformational changes | Sample purity, conformational heterogeneity, resolution limits |

| Chemical Inhibitors | Bafilomycin A1, chlorpromazine, NH4Cl, EIPA | Entry pathway characterization, kinetic studies | Inhibitor specificity, cellular toxicity, off-target effects |

| Visualization Tools | Fluorescent protein fusions, quantum dots, immunofluorescence | Live-cell entry tracking, co-localization studies | Fluorophore brightness, photostability, labeling efficiency |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Viral Entry for Antiviral Development

The precise molecular understanding of viral entry mechanisms has enabled the rational design of innovative antiviral strategies that target specific stages of the entry process. Entry inhibitors represent a growing class of antivirals that block the earliest stages of infection, potentially preventing establishment of viral replication entirely [4] [7]. These include receptor-binding inhibitors like maraviroc (a CCR5 antagonist for HIV-1), fusion inhibitors such as enfuvirtide (HIV-1 gp41 inhibitor), and endosomal acidification blockers [3] [7]. The recently developed decoy receptor molecules against flaviviruses demonstrate a particularly promising approach, leveraging structural insights from virus-receptor complexes to design soluble receptor fragments that effectively compete with cellular receptors for viral binding [8]. This strategy offers potential advantages over traditional antivirals by targeting conserved host structures rather than mutable viral elements, potentially imposing a higher genetic barrier to resistance development [8].

Beyond direct-acting antivirals, viral entry research informs vaccine design by identifying key antigenic sites on viral attachment and fusion proteins [4] [1]. Structural characterization of prefusion conformations of viral glycoproteins has enabled the engineering of stabilized immunogens that elicit potent neutralizing antibodies, as demonstrated by the success of prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 spike vaccines [7]. Additionally, the identification of broadly neutralizing antibodies against conserved receptor-binding sites or fusion intermediates provides templates for monoclonal antibody therapeutics and vaccine immunogen design [1]. Emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are further accelerating antiviral discovery, with platforms like Model Medicines' AI-driven platform identifying broad-spectrum polymerase inhibitors such as MDL-001 that target conserved viral domains across multiple virus families [9]. These computational approaches analyze vast datasets of viral sequences and structures to predict conserved, druggable pockets that are less prone to mutational escape, potentially yielding therapeutics with broader activity spectra against current and future viral threats [9].

Emerging Technologies and Research Frontiers

The field of viral entry research continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advances that enable increasingly sophisticated analyses. Quantitative proteomics methods have reached sensitivities and throughput capabilities that allow comprehensive mapping of dynamic protein interaction networks during viral entry, providing systems-level understanding of the complex host factor requirements [3]. These approaches can detect transient, low-affinity interactions that were previously missed by traditional biochemical methods, revealing previously unappreciated complexity in viral entry pathways. Similarly, single-particle tracking and live-cell imaging techniques now permit real-time visualization of individual virions during the entry process, revealing the dynamic spatial and temporal coordination of entry events with unprecedented resolution [7].

Looking forward, several emerging frontiers promise to further transform our understanding of viral entry mechanisms. Artificial intelligence is increasingly being integrated into the viral entry research pipeline, from target discovery and drug design to clinical trial optimization [9]. At IDWeek 2025, researchers highlighted AI multi-agent systems that can mine pathogen genomes for novel essential targets, generate initial inhibitor scaffolds, and evaluate pharmacological properties in silico before laboratory testing [9]. Additionally, the growing recognition of broad-spectrum antivirals that target conserved host pathways or viral domains represents a paradigm shift from pathogen-specific to pandemic-preparedness approaches [9]. These developments, combined with advanced structural biology techniques and gene editing technologies, are creating an increasingly powerful toolkit for deciphering the intricate molecular mechanisms of viral entry and developing next-generation countermeasures against existing and emerging viral threats.

Viruses, as obligate intracellular parasites, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to exploit host cell machinery and metabolic pathways to ensure their replication and survival. This process, known as molecular hijacking, represents a fundamental aspect of viral pathogenesis where viruses reprogram cellular processes to create an environment favorable for viral propagation. The host-virus interaction is a perpetual tug-of-war fought at multiple interfaces, from the cell surface to the nucleus [10]. Viruses systematically target master regulator proteins and disrupt critical metabolic processes to alter the host's metabolic environment [11]. This reprogramming provides viruses with more energy for replication and propagation while simultaneously evading host immune defenses. The study of these hijacking mechanisms not only reveals how viruses cause disease but also identifies potential therapeutic targets for antiviral drug development.

The molecular hijacking strategies employed by viruses are remarkably diverse, ranging from direct exploitation of host enzymes and metabolic pathways to sophisticated mimicry of cellular components. Recent research has illuminated how viral RNA structures can hijack or subvert host RNA polymerases, ribosomes, translation-associated enzymes, RNA processing systems, and antiviral immunity proteins [10]. Simultaneously, viruses encode specialized proteins that manipulate host cell structures and signaling networks. Through these multifaceted approaches, viruses effectively reengineer the host cell into a viral replication factory, often while circumventing detection by the immune system. Understanding these mechanisms provides critical insights into viral pathogenesis and reveals novel vulnerabilities that can be targeted therapeutically.

Key Mechanisms of Viral Hijacking

RNA Structure-Mediated Hijacking

Structured RNA elements represent major players at the forefront of virus-host interactions, serving as conduits for viral exploitation of host cellular machinery. Viral RNA structures frequently mimic existing cellular interfaces, functioning as doppelgängers that enable widespread viral mimicry of cellular interactions [10]. These structured elements often amalgamate distinct features from multiple host RNAs to form chimeras that simultaneously target various host systems for viral gains. Through this sophisticated structural mimicry, viral RNAs can hijack host RNA polymerases, ribosomes, translation-associated enzymes, RNA processing systems, modification machinery, transport systems, and antiviral immunity proteins [10].

Advanced visualization techniques have revealed complex RNA and ribonucleoprotein structures at virus-host interfaces, providing unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms of viral exploitation. These structures frequently have their roots or structural doppelgängers in existing cellular interfaces, suggesting that viruses have evolved to mimic native molecular interactions as an efficient hijacking strategy. The resulting chimeric RNA structures enable viruses to borrow and combine distinct features from several host RNAs, creating multifunctional elements that can simultaneously target multiple host systems. This RNA-level hijacking represents a fundamental strategy across diverse virus families to subvert host cell processes from within the core of cellular machinery.

Viroporins: Pore-Forming Viral Proteins

Viroporins are small hydrophobic transmembrane proteins encoded by viruses that self-oligomerize to form membrane-embedded pores facilitating ion transport. These viral proteins play critical roles in multiple stages of the viral life cycle by modulating ion homeostasis, disrupting host membrane integrity, and orchestrating key stages from viral entry to release [12]. Beyond facilitating viral propagation, viroporins exacerbate pathogenesis by disrupting cellular ion homeostasis and triggering proinflammatory responses through mechanisms such as NLRP3 inflammasome activation [12].

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Characterized Viroporins

| Virus | Viroporin | Classification | Amino Acids | Ion Selectivity | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus | M2 | IA/SP type I | 97 | H+, K+, Na+ | 4 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | E | IA/SP type I | 75 | K+, Ca2+ | 2/5 |

| Poliovirus | 2B | IIB/MP type II | 97 | Ca2+ | - |

| Ebola virus | Delta peptide | IA/SP type I | 40-49 | Cl⁻ | - |

| Human astrovirus | XP | IA/SP type I | 112 | - | - |

Viroporins are primarily classified into three structural categories based on their transmembrane domains (TMDs). Type I viroporins contain one TMD and are further subdivided into IA and IB subtypes based on membrane orientation. Type II viroporins possess two TMDs forming a transmembrane helix-turn-helix hairpin structure, with IIA and IIB subtypes distinguished by their terminal orientations. Type III viroporins contain three TMDs [12]. The functional characterization of viroporins typically employs electrophysiological techniques such as patch-clamp and planar lipid bilayers, though these approaches require validation in physiological contexts as heterologous expression systems may produce artifactual results [12].

Metabolic Reprogramming of Host Cells

Viruses fundamentally reprogram host cell metabolism to meet the substantial energy and biosynthetic demands of viral replication. This reprogramming involves targeting master regulator proteins and disrupting important metabolic processes, particularly in metabolic organs [11]. The metabolic alterations induced by viruses promote survival of infected cells while generating abundant energy and building blocks for viral replication and propagation. Viruses achieve this reprogramming through multiple strategies, including releasing molecules like miRNAs, interferons, and adipocytokines that affect both infected cells and distant organs involved in glucose and energy homeostasis [11].

The rewiring of host cell metabolism is particularly evident in the manipulation of central carbon metabolism. Many viruses induce a Warburg-like effect, shifting cells toward aerobic glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen, similar to observations in cancer cells. This glycolytic shift generates ATP rapidly while also providing metabolic intermediates for nucleotide, amino acid, and lipid biosynthesis – all essential components for new virion production. Additionally, viruses commonly enhance glutamine metabolism to replenish TCA cycle intermediates through anaplerosis and boost pentose phosphate pathway flux to generate NADPH for biosynthetic reactions and nucleotide precursors. This comprehensive metabolic restructuring represents a core hijacking strategy essential for efficient viral replication.

Mitochondrial Sabotage for Immune Evasion

Viruses have developed sophisticated mechanisms to sabotage mitochondrial function, particularly to evade host immune responses. Recent research has revealed how Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) encodes a viral Bcl-2 protein (vBcl-2) that binds to and activates the host enzyme NM23-H2, recruiting it to mitochondria where it provides GTP to power the mitochondrial fission machinery [13]. This triggers mitochondrial fragmentation at a critical time when these organelles should remain connected, preventing the assembly of the MAVS immune signaling platform that normally triggers Type I interferon responses – the cell's front-line antiviral defense [13].

This mitochondrial sabotage represents a sophisticated immune evasion strategy. By remodeling mitochondrial architecture, the virus destabilizes the entire immune signaling hub rather than merely blocking a single immune protein. In the absence of vBcl-2-induced mitochondrial fragmentation, interferon signaling activates two key antiviral proteins – TRIM22 and MxB – which trap virus particles in the nucleus and prevent their release [13]. Other herpesviruses, including Epstein-Barr virus, encode similar Bcl-2 proteins, suggesting that mitochondrial reshaping represents a conserved strategy across this virus family. This mechanism highlights how viruses can target fundamental cellular organelles to create an environment permissive for viral replication and dissemination.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Viral Hijacking

Structural and Biophysical Characterization

The structural characterization of virus-host interfaces requires sophisticated methodologies to visualize complex molecular interactions. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a powerful technique for determining high-resolution structures of viral and host proteins, ribonucleoprotein complexes, and membrane proteins such as viroporins [12]. This technique allows researchers to visualize macromolecular complexes in near-native states, providing insights into the molecular mechanisms of viral exploitation. Complementary to cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography continues to provide atomic-resolution structures of viral proteins in complex with host factors, revealing detailed interaction interfaces that can be targeted therapeutically.

Electrophysiological techniques are essential for characterizing the functional properties of viroporins. Patch-clamp electrophysiology and planar lipid bilayer measurements enable direct assessment of ion channel activity, selectivity, and gating mechanisms [12]. However, these approaches carry inherent limitations as they often require heterologous expression of candidate channels or reconstitution of isolated peptides into artificial membranes, which may not fully recapitulate physiological cellular environments. To address these challenges, researchers are increasingly combining electrophysiological approaches with molecular dynamics simulations and mutational analyses to confirm ion channel activity by perturbing key residues involved in channel gating and ion selectivity [12].

Molecular Imaging of Viral Pathogenesis

Molecular imaging represents a valuable tool for non-invasive study of viral pathogenesis in both clinical and research settings. Unlike traditional microbiological detection methods that provide single timepoint snapshots, molecular imaging enables longitudinal whole-body data collection, allowing pathological changes to be monitored and detected in unexpected body regions [14]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding systemic viral infections, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic when what was initially considered a respiratory illness was revealed to cause multi-systemic pathology [14].

Table 2: Molecular Imaging Modalities for Viral Pathogenesis Studies

| Imaging Modality | Probe Types | Spatial Resolution | Key Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET (Positron Emission Tomography) | Positron-emitting radionuclides (e.g., 18F, 89Zr) | 1-2 mm (clinical); <1 mm (preclinical) | Metabolic imaging, receptor targeting | High sensitivity, quantitative capabilities |

| SPECT (Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography) | Gamma-emitting radionuclides (e.g., 99mTechnetium, 123Iodine) | 1-2 mm (clinical); 0.5-1 mm (preclinical) | Receptor occupancy, perfusion imaging | Multi-isotope imaging, wider availability |

| Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) | Endogenous metabolites (e.g., choline, creatine) | 1-10 mm³ voxels | Metabolic pathway analysis | No ionizing radiation, simultaneous anatomical and metabolic data |

Nuclear imaging techniques, particularly PET and SPECT, offer high detection sensitivity and a growing repertoire of probes for studying viral infections. PET imaging uses positron-emitting isotopes that generate detectable annihilation photons, enabling 3D image reconstruction of functional processes [14]. SPECT relies on probes that undergo gamma decay, releasing photons detectable by gamma cameras. While PET generally offers higher sensitivity and resolution in clinical settings, SPECT provides the advantage of potential multi-isotope imaging to simultaneously monitor multiple biological targets [14]. These imaging modalities are frequently combined with anatomical imaging techniques like CT or MRI to correlate molecular signals with structural changes.

Proteomic and Interaction Network Analysis

The systematic mapping of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) between viral and host proteins provides crucial insights into hijacking mechanisms. Human-virus PPIs help elucidate the molecular basis of viral infection and host response, guiding the development of targeted antiviral strategies [15]. These interaction networks are typically represented with nodes representing proteins and edges representing physical interactions, revealing how viral proteins rewire host cellular machinery. Research has demonstrated that viral proteins often interact with highly connected host proteins, suggesting targeting of hub proteins in cellular networks [15].

Advanced technologies for studying interactomes include yeast two-hybrid systems, affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry, and protein complementation assays. These approaches have revealed that viruses with small genomes, such as HIV, interact extensively with host proteins to compensate for their limited coding capacity [15]. Meanwhile, larger DNA viruses like herpesviruses encode more self-sufficient networks with complex intraviral interactomes. The interfaces of these protein interactions represent critical determinants of binding specificity, with electrostatic and structural properties governing recognition. Mutational analyses of these interfaces have revealed how subtle changes can dramatically alter interaction networks and viral pathogenicity.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Viral Hijacking Mechanisms

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Tools | AlphaFold, Cryo-EM, Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Viroporin structure determination, RNA-protein complexes | Protein structure prediction, complex visualization |

| Metabolic Assays | Seahorse Analyzer, Stable Isotope Tracers, Mass Spectrometry | Metabolic flux analysis, pathway utilization | Real-time metabolic measurements, pathway mapping |

| Interaction Mapping | Yeast Two-Hybrid, AP-MS, BioID | Host-virus protein interaction networks | Proximity labeling, complex identification |

| Electrophysiology | Patch Clamp, Planar Lipid Bilayers | Viroporin channel characterization | Ion channel activity, selectivity, and gating |

| Molecular Imaging | 18F-FDG, 89Zr-labeled antibodies, Radioactive nucleotides | In vivo tracking of infection, metabolic changes | Non-invasive monitoring, whole-body visualization |

Methodologies for Key Experiments

Viroporin Characterization Workflow

The comprehensive characterization of viroporins requires an integrated multidisciplinary approach. A robust workflow begins with bioinformatic analysis to identify potential viroporin candidates based on sequence features such as hydrophobic domains and propensity for membrane insertion. This is followed by heterologous expression in model systems like Xenopus oocytes or mammalian cell lines for initial functional screening. Electrophysiological characterization using patch-clamp or planar lipid bilayer measurements assesses ion channel activity, selectivity, and gating properties [12]. Structural analysis via cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography provides high-resolution insights into oligomeric states and pore architectures. Crucially, genetic validation through mutational analysis confirms the functional significance of key residues, while cell-based assays establish physiological relevance in the context of viral infection [12].

Metabolic Reprogramming Analysis

Investigating virus-induced metabolic reprogramming requires a combination of metabolomic, fluxomic, and molecular biology techniques. A comprehensive workflow begins with infection of relevant cell culture models followed by metabolite extraction at specific timepoints. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics enables quantification of metabolite abundance changes across central carbon metabolism, including glycolysis, TCA cycle, pentose phosphate pathway, and nucleotide metabolism [11]. Stable isotope tracing with 13C- or 15N-labeled nutrients (e.g., 13C-glucose, 13C-glutamine) allows determination of metabolic flux through specific pathways. Complementary transcriptional and proteomic analyses identify regulatory changes driving metabolic alterations. Functional validation through pharmacological inhibition or genetic knockdown of key metabolic enzymes confirms the essentiality of specific pathways for viral replication [11].

Mitochondrial Manipulation Assay

The investigation of viral manipulation of mitochondrial dynamics requires specialized methodologies focused on organelle morphology and function. A typical experimental workflow begins with infection of appropriate host cells, followed by fixation and immunostaining of mitochondrial markers (e.g., TOMM20, COX IV) and viral proteins at various timepoints. High-resolution confocal microscopy enables qualitative and quantitative assessment of mitochondrial morphology, distinguishing between fused networks and fragmented puncta [13]. Functional assays measuring mitochondrial membrane potential (using dyes like TMRE or JC-1), ATP production, and reactive oxygen species generation provide insights into bioenergetic alterations. Immunoprecipitation of viral proteins with subsequent mass spectrometry identification reveals interacting host partners, while genetic approaches (siRNA, CRISPR) validate the requirement of specific host factors for viral-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation [13].

The systematic hijacking of host cell machinery and metabolic pathways represents a cornerstone of viral pathogenesis. Through diverse mechanisms including RNA structural mimicry, viroporin-mediated membrane manipulation, metabolic reprogramming, and mitochondrial sabotage, viruses extensively reengineer host cells to support their replication while evading immune detection. The investigation of these processes requires sophisticated methodological approaches spanning structural biology, molecular imaging, interactome mapping, and metabolic analysis. As our understanding of these hijacking mechanisms deepens, new therapeutic vulnerabilities are being revealed that target the essential interfaces between viruses and their host cells. Future research directions will likely focus on developing compounds that disrupt these critical host-virus interactions, potentially leading to broad-spectrum antiviral strategies that are less susceptible to viral resistance.

Viral pathogenesis is defined as the process by which viral infection leads to disease, a complex interplay that extends far beyond simple cell killing to encompass sophisticated mechanisms of host manipulation [16]. At the heart of successful viral colonization lies the critical ability to evade, subvert, or outright disable host immune defenses. This biological arms race has driven the evolution of remarkably diverse immune evasion strategies, which can be broadly categorized into two fundamental approaches: direct interference through viral protein interactions and indirect manipulation through epigenetic silencing of host defense genes. Understanding these tactics is not merely an academic exercise but a pressing necessity for developing next-generation antiviral therapeutics and vaccines. This review synthesizes current research on how viruses employ molecular sabotage at both the protein and epigenetic levels to establish infection, with profound implications for pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention.

The following table summarizes the core immune evasion mechanisms discussed in this review:

Table: Core Categories of Viral Immune Evasion Mechanisms

| Evasion Category | Molecular Mechanism | Representative Viruses | Primary Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Protein Interaction | Viral proteins bind and inhibit key immune signaling molecules (e.g., MAVS, STING) | SARS-CoV-2, PRV [17] [18] | Blocks downstream interferon and cytokine production |

| Receptor Modulation | Mutations in surface proteins alter binding interfaces to evade neutralizing antibodies | SARS-CoV-2 (e.g., E484K, T478K) [19] | Reduces antibody neutralization while maintaining host receptor binding |

| Epigenetic Silencing | Recruitment of host epigenetic modifiers (e.g., DNMT1) to immune gene promoters | Tumor viruses via FOXM1 [20], Endogenized giant viruses [21] | Heritable suppression of immune sensor and effector gene expression |

| Decoy & Mimicry | Viral production of cytokine mimics or decoy receptors | KSHV (vIL-6) [22] | Dysregulates host inflammatory responses and cell signaling |

Viral Protein Interactions: Direct Sabotage of Immune Signaling

Viruses deploy a molecular arsenal of proteins that directly target and disrupt the host's immune signaling apparatus. This frontline evasion strategy involves precise protein-protein interactions that intercept critical immune activation pathways at their most vulnerable nodes.

SARS-CoV-2: Master of Interferon Interdiction

SARS-CoV-2 exemplifies sophisticated interferon (IFN) pathway evasion. The virus delays the induction of type I and III interferons (IFN-I and IFN-III) at the initial infection site, while paradoxically causing systemic IFN-I priming in distal organs [18]. This dysregulation is a key contributor to COVID-19 severity. The primary cellular defense against RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 is the MDA5-mediated recognition of viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structures, which triggers a signaling cascade through the mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS), leading to the activation of transcription factors IRF3 and NF-κB and the production of IFN-I/III [18]. SARS-CoV-2 thwarts this through multiple non-structural proteins (Nsps) and accessory proteins that:

- Block MDA5 Activation: Viral proteins prevent the recognition of dsRNA replication intermediates by MDA5.

- Interfere with MAVS Signaling: Key viral proteins disrupt the critical relay between RNA sensing and downstream transcription.

- Inhibit IRF3 Nuclear Translocation: Even if sensing occurs, the final step of interferon gene activation is often blocked.

This multi-layered interference creates a critical delay in the antiviral response, allowing the virus to establish a foothold and replicate unchecked during the earliest stages of infection [18].

Spike Protein Mutations: Balancing Affinity and Evasion

Beyond innate immune sabotage, viral surface proteins continuously evolve to evade adaptive immunity. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) is a hotspot for mutations that fine-tune the trade-off between ACE2 receptor affinity and antibody escape [19]. For instance:

- T478K: This prevalent mutation in Delta and Omicron variants enhances ACE2 binding through structural rigidification and salt bridge formation (e.g., K478-D30), favoring increased transmissibility [19].

- E484K: This mutation, a hallmark of Beta and Gamma variants, balances antibody evasion (e.g., against LY-CoV555) with receptor stabilization via compensatory interactions (e.g., K484-D38) [19].

- F490S and G496S: These mutations act as stealth adaptations, subtly destabilizing the ACE2 interface or introducing metastability without fully disrupting binding, thereby facilitating immune evasion [19].

Table: Functional Impact of Key SARS-CoV-2 Spike Mutations

| Mutation | Variant Association | Impact on ACE2 Binding | Immune Evasion Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| T478K | Delta, Omicron | Enhanced | Electrostatic complementarity and salt bridge formation |

| E484K | Beta, Gamma | Stabilized | Disruption of antibody-binding sites (e.g., LY-CoV555) |

| T478A | Laboratory study | Weakened | Polarity loss and interface relaxation |

| T478E | Laboratory study | Weakened | Electrostatic repulsion at binding interface |

| F490S | Circulating variants | Subtly destabilized | Disruption of hydrophobic interactions with ACE2's K353 |

| G496S | Circulating variants | Subtly destabilized | Introduction of metastability at the RBD-ACE2 interface |

Herpesvirus Strategies: Broad-Spectrum Signaling Disruption

Other viruses employ similar direct interference tactics. The Pseudorabies virus (PRV), an alphaherpesvirus, establishes persistent latent infections by effectively evading the host's antiviral innate immune response through sophisticated strategies that disrupt immune signaling pathways [17]. Similarly, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) encodes viral proteins like latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) and viral interleukin-6 (vIL-6) that manipulate host cell survival pathways, including PI3-K signaling and Rho GTPase regulation, to drive oncogenesis while evading immune detection [22].

Epigenetic Silencing: The Stealth Approach to Immune Evasion

Beyond direct protein interactions, viruses have co-opted the host's epigenetic machinery to achieve long-term, heritable suppression of antiviral defense genes. This stealth approach represents a more profound and sustained form of immune subversion.

FOXM1-Mediated Silencing of the DNA Sensing Pathway

A paradigm of viral-induced epigenetic silencing has been elucidated in virological research, particularly in the context of viral oncogenesis. The transcription factor FOXM1, often dysregulated by viruses, creates an immune-suppressive environment by epigenetically silencing the cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway [20]. The mechanism is a multi-step process:

- FOXM1 recruits a DNMT1-UHRF1 complex to the promoter of the STING gene.

- This complex deposits repressive DNA methylation marks, effectively silencing STING expression.

- Silenced STING prevents the activation of the unfolded protein response protein CHOP, which is required to activate the expression of the stress ligand ULBP1.

- The lack of ULBP1 on the cell surface blocks the NKG2D-NKG2DL interaction, which is critical for priming natural killer (NK)- and T cell-mediated cytotoxicity [20].

This elegant epigenetic sabotage allows virus-infected or transformed cells to evade detection and destruction by the innate and adaptive immune system. Cancer patients with higher FOXM1 and DNMT1, and lower STING and ULBP1, experience worse survival and poor response to immunotherapy, underscoring the clinical significance of this pathway [20].

Diagram Title: FOXM1 Epigenetic Silencing of Immune Sensing

Host-Directed Silencing of Endogenized Viral Elements

The host also leverages epigenetic mechanisms defensively to silence endogenized viral DNA. Studies in Acanthamoeba, a protist model for giant virus interactions, reveal that newly acquired viral integrations are disproportionately found in sub-telomeric regions and are hypermethylated and highly condensed [21]. This host-induced heterochromatic silencing suppresses the expression of recently acquired viral DNA, preventing potential toxicity or genome instability. The trajectory of viral sequences follows a clear path: (i) integration of viral DNA, (ii) epigenetic suppression via methylation and condensation, and (iii) long-term deterioration of viral genomes by point mutation and mobile element colonization [21]. This demonstrates that epigenetic silencing is a universal strategy in the host-virus arms race, employed by both parties for survival advantage.

Experimental Methodologies for Deconstructing Immune Evasion

Unraveling these complex evasion tactics requires a robust and multidisciplinary experimental toolkit. The following section outlines key protocols and reagents essential for probing both protein-level and epigenetic evasion mechanisms.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations for Protein Interaction Analysis

Objective: To assess the biophysical impacts of viral protein mutations on host receptor binding and antibody evasion at atomic-level resolution [19].

Protocol:

- Protein Structure Preparation: Obtain structural coordinates of host receptors (e.g., ACE2, PDB ID: 1R42) and viral proteins (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD, PDB ID: 6M0J) from the Protein Data Bank. Introduce desired mutations into the viral protein using molecular visualization software like PyMOL [19].

- System Setup: Solvate the protein-protein complex in a water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) and add physiological ion concentrations (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) to mimic the cellular environment.

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Use molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM) to minimize the system's energy and gradually equilibrate it under specified temperature and pressure conditions (e.g., NPT ensemble at 310 K).

- Production MD Run: Perform extensive, nanosecond-to-microsecond timescale simulations to sample the conformational dynamics of the complex. Trajectories are analyzed for:

- Binding Free Energy: Calculate using methods like Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) to quantify interaction strength.

- Salt Bridge & H-bond Analysis: Monitor formation, breakage, and stability of key electrostatic interactions.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Measure per-residue flexibility to identify mutations that cause rigidification or relaxation of the binding interface.

- Validation: Correlate in silico findings with in vivo viral fitness and neutralization assays from animal models or clinical isolates [19].

Mapping Epigenetic Landscapes via scRNA-seq and Methylation Analysis

Objective: To identify viral-mediated epigenetic reprogramming of host immune genes and its functional consequences on the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) [20].

Protocol:

- Perturbation and Model Systems: Use CRISPR-Cas9 or shRNA to knockout/down candidate viral or host factors (e.g., FOXM1) in relevant cell lines (e.g., triple-negative breast cancer models like E0771 or MDA-MB-231). Establish syngeneic tumors in immunocompetent mice [20].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq):

- Tissue Processing: Create single-cell suspensions from harvested control and knockout tumors.

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Use platforms like 10x Genomics to generate barcoded scRNA-seq libraries. Sequence to an appropriate depth (e.g., 50,000 reads/cell).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Perform unsupervised clustering and cell population annotation using known markers (e.g., Cd3e for T cells, Ncr1 for NK cells). Conduct gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to identify differentially activated pathways [20].

- DNA Methylation Analysis:

- DNA Extraction & Bisulfite Treatment: Treat genomic DNA from cells with bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils.

- Targeted Sequencing: Perform bisulfite sequencing (e.g., Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing or targeted approaches) on promoters of genes of interest (e.g., STING).

- Analysis: Map sequencing reads and calculate methylation percentages at individual CpG sites. Compare profiles between control and experimental groups.

- Functional Immune Assays: Validate findings using flow cytometry to quantify immune cell infiltration (CD45+, CD8+ T cells, Tregs) and surface expression of stress ligands (e.g., ULBP1). Use cytotoxicity assays to measure NK and T cell killing capacity [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A comprehensive investigation of immune evasion requires a carefully selected set of reagents and model systems, as detailed below.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immune Evasion Studies

| Reagent / Material | Specific Example | Function in Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | sgRNAs targeting FOXM1 [20] | Gene knockout to validate the functional role of a host factor in immune evasion. |

| Stable Cell Lines | FOXM1-knockout E0771 or MDA-MB-231 cells [20] | Provide a consistent in vitro and in vivo model for studying the loss-of-function effects. |

| Syngeneic Mouse Models | Immunocompetent C57BL/6J mice [20] | Enable the study of immune evasion in a context of a fully functional immune system. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | Anti-CD45, CD8, CD4, FOXP3, CD11b, CD11c, MHC-II [20] | Phenotype and quantify immune cell populations infiltrating the tumor or infected tissue. |

| scRNA-seq Platform | 10x Genomics Chromium [20] | Unbiased profiling of the transcriptome of every cell in a complex tissue sample (TIME). |

| Protein Structural Data | PDB IDs: 6M0J (SARS-CoV-2 RBD), 1R42 (ACE2) [19] | Starting points for molecular dynamics simulations and structural analysis of protein interactions. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMACS [19] | Simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules to study dynamic protein behavior. |

The intricate interplay between viral protein interactions and epigenetic silencing represents a cornerstone of modern viral pathogenesis research. Direct protein interference allows for rapid, potent shutdown of specific immune pathways, while epigenetic reprogramming offers a stealthier, more sustained strategy for immune avoidance. The convergence of these tactics—observed in diverse viruses from SARS-CoV-2 to KSHV—highlights their fundamental importance to viral fitness and persistence.

Future research must focus on the dynamic intersection of these fields. Key questions remain: How do initial protein interactions trigger long-term epigenetic changes? Can the repressive epigenetic marks laid down by viruses be therapeutically erased? The answers will hinge on integrated methodologies that combine structural biology, omics technologies, and immunology. The experimental frameworks and tools outlined herein provide a roadmap for this work. By continuing to deconstruct these evasion tactics, researchers can identify novel vulnerabilities, paving the way for host-directed therapies that bolster innate immune recognition and break the cycle of viral persistence and pathogenesis.

Viral tropism is defined as the ability of a virus to infect and replicate within specific cell types, tissues, or host species while encountering restrictions in others [23]. This fundamental property shapes viral pathogenesis, determining the clinical manifestations of disease, the efficiency of transmission, and the potential for cross-species spread. The molecular basis of tropism involves a complex interplay between viral surface proteins and host cell factors, which govern every step of the viral life cycle from initial attachment to progeny release. Understanding these determinants is crucial for predicting disease outcomes, developing targeted antiviral therapies, and designing effective vaccines.

Within the broader context of viral pathogenesis research, elucidating tropism mechanisms provides a framework for explaining why respiratory viruses predominantly cause cough and shortness of breath, why enteric viruses lead to gastrointestinal symptoms, and why neurotropic viruses can cause encephalitis and long-term neurological sequelae [24] [25]. Furthermore, variations in tropism can explain differences in transmission dynamics and pathogenicity between related viruses, as exemplified by the distinct clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 despite their genetic similarity [24]. This guide examines the molecular mechanisms underlying tissue-specific viral pathogenesis, current methodologies for tropism investigation, and the implications for therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Viral Entry and Cellular Invasion

Initial Attachment and Receptor Interactions

The first critical determinant of cellular tropism is viral attachment to host cell surfaces. This process is mediated through specific interactions between viral surface proteins and host cell receptors:

- Animal viruses typically utilize plasma membrane receptors for cell entry, with different virus families employing distinct receptor types. For example, SARS-CoV-2 primarily engages the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor through its Spike protein, initiating the entry process [26].

- Plant viruses face the unique challenge of the plant cell wall, which acts as a physical barrier restricting diffusion of macromolecules larger than 60 kDa. These viruses bypass this barrier by exploiting mechanical damage or vector organisms to introduce viral particles directly into plant tissues [23].

Beyond primary receptor binding, many viruses require co-receptors or attachment factors that enhance binding efficiency or trigger conformational changes necessary for entry. Proteolytic priming of viral surface proteins by host proteases represents another critical tropism determinant, as the distribution of these activating enzymes varies across tissues [26].

Intracellular Trafficking and Membrane Fusion

Following attachment, viruses employ diverse entry mechanisms to penetrate cellular membranes and deliver their genetic material into the host cell cytoplasm:

- Direct membrane fusion at the cell surface is utilized by some viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 when primed by plasma membrane proteases like TMPRSS2.

- Receptor-mediated endocytosis pathways are hijacked by many viruses, with subsequent fusion events occurring within endosomal compartments. These pathways often depend on endo-lysosomal proteases (e.g., cathepsins) that further process viral proteins to activate fusion potential.

- Viroporin activity facilitates the release of viral genomes from endocytic compartments into the cytoplasm. These small, hydrophobic viral proteins oligomerize to form membrane-embedded pores that modulate ion homeostasis and disrupt host membrane integrity [12].

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Characterized Viroporins

| Virus | Viroporin | Classification | Amino Acids | Ion Selectivity | Oligomeric State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus | M2 | IA/SP type I | 97 | H+, K+, Na+ | 4 |

| SARS-CoV-1 | E | IA/SP type I | 76 | K+, Ca2+ | 5 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | E | IA/SP type I | 75 | K+, Ca2+ | 2/5 |

| Poliovirus | 2B | IIB/MP type II | 97 | Ca2+ | - |

| Ebola virus | Delta peptide | IA/SP type I | 40-49 | Cl⁻ | - |

Host and Viral Determinants of Tissue Specificity

Host Factors Governing Tropism

Cellular susceptibility to viral infection is governed by the constellation of host factors that either facilitate or restrict the viral life cycle:

- Entry factor expression patterns directly determine which tissues can be initially infected. CRISPR activation screens have identified numerous membrane proteins beyond the canonical ACE2 receptor that can modulate SARS-CoV-2 entry, including the potassium channel KCNA6 and the endo-lysosomal protease legumain (LGMN) [26].

- Intrinsic immunity factors, such as restriction factors and RNA interference machinery, vary in expression and activity across cell types, creating barriers to infection in non-permissive cells.

- Metabolic and biosynthetic capacity of host cells must support viral replication, with different cell types providing varying environments conducive to viral gene expression and particle assembly.

The interferon response and other antiviral signaling pathways demonstrate cell-type-specific activation patterns that significantly influence tropism. Neuronal cells, for instance, may exhibit attenuated interferon responses compared to epithelial cells, potentially explaining the persistence of certain viruses in neural tissue [25].

Viral Determinants of Tissue Specificity

Viral genomes encode specific proteins that actively dictate tropism through interactions with host cell components:

- Attachment proteins and their genetic variability represent the primary viral determinant of tropism. Sequence variations in these proteins can alter receptor binding affinity or enable usage of alternative receptors, thereby expanding or restricting host range.

- Movement proteins in plant viruses facilitate intercellular transport through plasmodesmata by modifying size exclusion limits, effectively governing which tissues become infected systemically [23].

- Viral countermeasures to host restriction factors, such as RNA silencing suppressors in plants and interferon antagonists in animals, exhibit cell-type-specific efficacy that shapes tropism [23].

The genetic plasticity of viruses allows rapid adaptation to new cell types through mutations in tropism-determining regions. This evolutionary capacity is particularly significant for RNA viruses with high mutation rates, enabling tropism expansion that may facilitate cross-species transmission and epidemic emergence.

Quantitative Analysis of Tropism and Replication Kinetics

Comparative Viral Replication Profiles

Replication kinetics vary significantly across cell types and between related viruses, providing quantitative insights into tropism determinants. A comparative study of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV demonstrated distinct replication patterns that correlate with their differing clinical manifestations:

- SARS-CoV-2 replicated to comparable levels in human intestinal (Caco2) and pulmonary (Calu3) cells over 120 hours, whereas SARS-CoV replicated significantly more efficiently in intestinal cells [24].

- SARS-CoV-2, but not SARS-CoV, demonstrated modest replication in neuronal (U251) cells, potentially explaining neurological manifestations such as confusion, anosmia, and ageusia in COVID-19 patients [24].

- SARS-CoV-2 consistently induced delayed and milder cell damage compared to SARS-CoV in non-human primate cells, possibly contributing to its high transmission efficiency by enabling extended asymptomatic shedding [24].

Table 2: Replication Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 Versus SARS-CoV Across Cell Lines

| Cell Line | Tissue Origin | SARS-CoV-2 Replication | SARS-CoV Replication | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco2 | Intestinal | High | Very High | p=0.0098 |

| Calu3 | Pulmonary | High | Moderate | p=0.52 (NS) |

| U251 | Neuronal | Modest | Undetectable | p=0.036 |

| VeroE6 | Non-human primate kidney | High | High | Cell damage significantly milder for SARS-CoV-2 (p=0.016) |

Evolutionary Implications of Cellular Tropism

Cellular tropism has profound implications for viral evolution and long-term adaptation to host species:

- Viruses infecting epithelial cells with high turnover rates evolve significantly faster than those infecting long-lived cells such as neurons [27]. This correlation between target cell and substitution rate suggests that cellular division rates directly influence viral evolutionary dynamics.

- The mutation rates of RNA viruses do not fully explain substitution rate variation, indicating that ecological factors like cell tropism play crucial roles in shaping viral evolvability [27].

- Transmission bottlenecks and selective pressures differ across tissues, creating distinct evolutionary trajectories for viruses with different tropism profiles.

Methodologies for Tropism Investigation

Advanced Screening Technologies

Modern approaches to tropism research employ high-throughput methodologies that enable systematic identification of host factors influencing viral infection:

- CRISPR-based screening platforms, particularly CRISPR activation (CRISPRa), allow functional interrogation of host factors by enabling targeted gene overexpression in combination with viral challenge models. Membrane-wide CRISPRa screens have identified novel host factors such as LGMN and KCNA6 that promote SARS-CoV-2 entry in specific cellular contexts [26].

- Single-cell RNA sequencing coupled with barcoded viral libraries enables multiplex assessment of transduction efficiency and specificity across complex cell populations. This technology maps how viral variants transduce individual cells within heterogeneous tissues like human cerebral and ocular organoids [28].

Experimental Models for Tropism Studies

Physiologically relevant model systems are essential for accurate tropism determination:

- Organoid cultures recapitulate the cellular complexity of human tissues, providing platforms for tropism studies that bridge the gap between conventional cell lines and in vivo models. Cerebral and ocular organoids have been used successfully to evaluate adeno-associated virus (AAV) tropism for gene therapy applications [28].

- Animal models with humanized receptor expression patterns enable assessment of tropism determinants in the context of intact physiological systems, including immune responses and tissue architecture.

- Explant cultures of human tissues maintain native cellular environments and receptor distributions, offering valuable insights into human tropism without ethical concerns of human challenge studies.

Experimental Protocols for Key Tropism Assays

Multiplexed Tropism Screening in Organoids

This protocol enables high-resolution assessment of viral tropism across complex cell populations using barcoded viral libraries and single-cell RNA sequencing:

Viral Library Preparation:

- Engineer barcoded AAV variants by introducing unique nucleotide sequences after the transgene stop codon in plasmid backbones.

- Package AAV libraries using serotype-specific capsid plasmids via triple transfection of 293AAV cell lines.

- Purify viruses by benzonase treatment to remove unpackaged nucleic acids and concentrate by ultracentrifugation [28].

Organoid Infection and Processing:

- Culture cerebral or ocular organoids from human embryonic stem cells using established differentiation protocols.

- Infect organoids with pooled AAV library at appropriate multiplicity of infection.

- After 72 hours, dissociate organoids to single-cell suspensions and prepare libraries for single-cell RNA sequencing using platform-specific protocols [28].

Data Analysis and Deconvolution:

- Process sequencing data through Cell Ranger software to simultaneously identify cell types and associated AAV barcodes.

- Visualize results in Seurat to generate matrices of AAV serotype transduction efficiency versus human cell types.

- Validate top candidates from screening in non-human primate models to confirm tropism patterns [28].

Membrane-Wide CRISPRa Screening for Host Factors

This approach identifies host membrane proteins that modulate viral entry through targeted gene activation:

CRISPRa System Establishment:

- Engineer HEK293FT cells with the synergistic activation mediator (SAM) system.

- Generate isogenic lines with (ACE2 OE) or without (WT) ACE2 overexpression to distinguish ACE2-dependent and independent factors [26].

Library Design and Screening:

- Design a customized sgRNA library targeting approximately 6,213 known membrane protein genes (~24,000 sgRNAs total including non-targeting controls).

- Transduce cells with the sgRNA library at low multiplicity to ensure single guide integration.

- Infect cells with SARS-CoV-2 Spike-pseudotyped lentiviruses encoding zeocin resistance at high and low MOI.

- Select infected cells with zeocin for 7-14 days before harvesting genomic DNA for sgRNA sequencing [26].

Hit Validation: