Navigating the Minefield: A Comprehensive Guide to Viral Database Sequence Error Management and Taxonomic Classification

This article provides a systematic review of the current landscape of viral sequence databases, focusing on the critical challenges of data quality, taxonomic errors, and curation strategies.

Navigating the Minefield: A Comprehensive Guide to Viral Database Sequence Error Management and Taxonomic Classification

Abstract

This article provides a systematic review of the current landscape of viral sequence databases, focusing on the critical challenges of data quality, taxonomic errors, and curation strategies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the origins and types of pervasive sequence errors, evaluates advanced computational and machine learning methods for classification and host prediction, outlines practical strategies for error mitigation and database optimization, and compares the performance of leading taxonomic classification tools. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to select appropriate databases, implement robust quality control measures, and improve the accuracy and reproducibility of viral genomics research, ultimately strengthening downstream applications in outbreak management and therapeutic development.

Understanding the Viral Database Landscape: Sources and Spectra of Sequence Errors

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary root causes of errors in public sequence databases like NCBI NR? Errors in databases like NCBI NR originate from three main sources: user metadata submission errors during data deposition, contamination in biological samples (e.g., from soil bacteria in a plant sample), and computational errors from tools that predict annotations based on homology to existing, potentially flawed, sequences [1]. These errors are then propagated as the databases grow.

Q2: How widespread is the problem of taxonomic misclassification? The problem is significant. One large-scale study identified over 2 million potentially misclassified proteins in the NR database, accounting for 7.6% of the proteins with multiple distinct taxonomic assignments [1]. In the curated RefSeq database, an estimated 1% of prokaryotic genomes are affected by taxonomic misannotation [2].

Q3: What is a common consequence of using a database with unspecific taxonomic labels? When sequences are annotated to a broad, non-specific taxon (e.g., merely "Bacteria"), it prevents precise identification in downstream analysis. This lack of specificity precludes crucial tasks like species-level classification, which is vital for clinical diagnostics and ecological studies [2].

Q4: Beyond contamination, what other issues affect reference databases? While contamination is a well-known issue, other pervasive problems include taxonomic misannotation, inappropriate sequence inclusion or exclusion criteria, and various sequence content errors. These issues are often inherited because many metagenomic tools simply mirror resources like NCBI GenBank and RefSeq without additional curation [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Suspected Taxonomic Misclassification in Your Analysis

Problem: Your metagenomic analysis returns results with unexpected or taxonomically implausible organisms (e.g., detecting turtle DNA in human gut samples [2]).

Solution: Follow this workflow to identify and correct for potential misclassifications.

Experimental Protocol: Heuristic Detection of Misclassified Sequences

This protocol is based on a method demonstrated to have 97% precision and 87% recall in detecting misclassified proteins [1].

- Data Acquisition: Download the latest NCBI NR database files.

- Identify Ambiguous Annotations: Isolate sequences that have more than one distinct taxonomic assignment in their metadata.

- Generate Clusters: Cluster all sequences at 95% sequence similarity.

- Apply Heuristic Filters:

- Provenance & Frequency: For each cluster, compare the taxonomic assignments from manually curated (high-quality) databases (e.g., RefSeq, SwissProt) against those from non-curated databases. The most frequent annotation from curated sources is often the correct one.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Automatically generate a phylogenetic tree for the sequences in a cluster. Sequences whose annotations place them on a distant branch from the cluster's consensus are likely misclassified.

- Propose Correction: For a sequence flagged as misclassified, reassign its taxonomy to the most probable taxonomic label based on the heuristic analysis above.

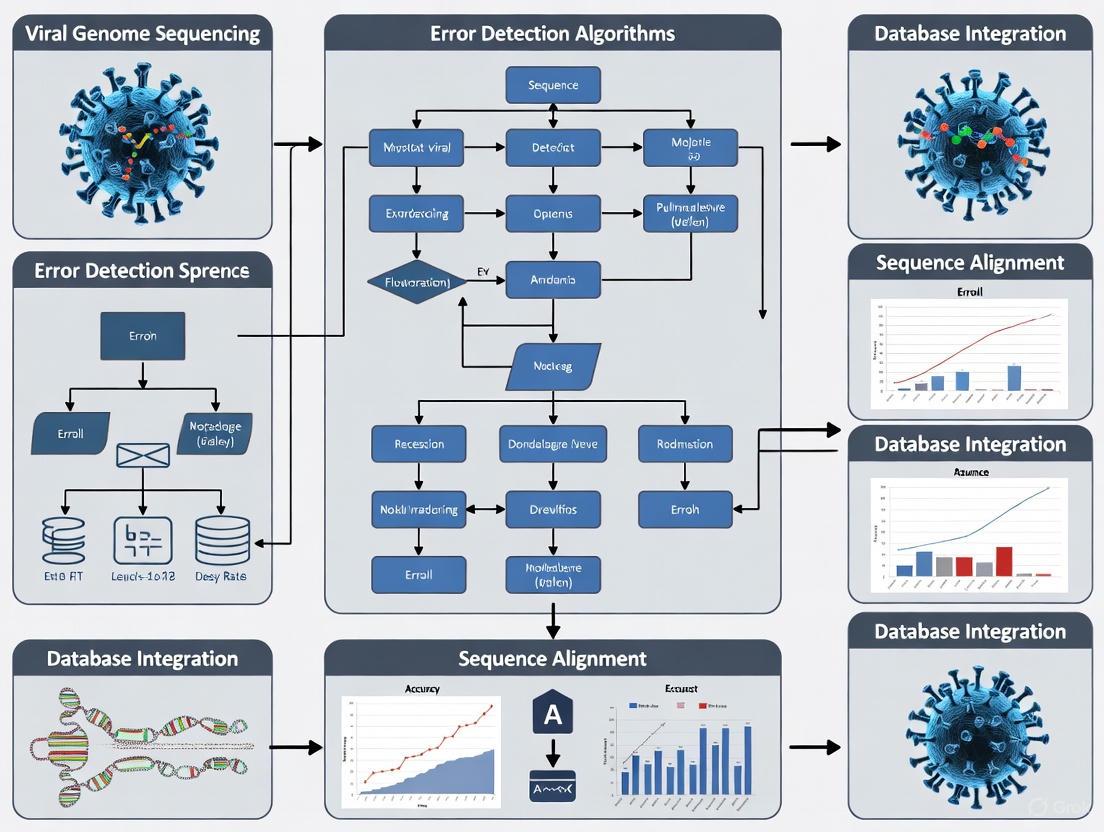

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for this diagnostic process:

Issue 2: Managing the Risk of Error Propagation

Problem: Your research relies on public repositories, but you are concerned that existing errors could compromise your results and lead to error propagation in your own publications.

Solution: Adopt a Threat and Error Management (TEM) framework, adapted from aviation safety, to proactively manage database-related risks [3] [4].

Methodology: Implementing a TEM Framework for Bioinformatics

Identify Threats: Actively recognize potential database issues (Threats) before and during your analysis.

- Anticipated Threats: Known issues like common contaminants (e.g., human sequence contamination in bacterial genomes [1]) or specific genera with high error rates (e.g., Aeromonas has reported 35.9% discordance [2]).

- Unexpected Threats: A novel misannotation in a previously trusted taxonomic group.

- Latent Threats: Systemic issues like default database configurations in software that may be unsuitable for your specific research question [2].

Prevent and Detect Errors: Implement countermeasures to prevent threats from causing analytical errors.

- Systemic Countermeasures: Use curated subset databases (e.g., RefSeq over GenBank where possible), employ contamination screening tools like VecScreen, and utilize bioinformatic tools designed to detect misclassified sequences [1] [2].

- Individual & Team Countermeasures:

- Planning: Brief your team on known database threats relevant to your project.

- Execution: Actively monitor analytical outputs for red flags (e.g., unexpected taxa).

- Review: Hold regular data review meetings to challenge and validate findings.

Manage Undesired States: If an error is not caught and leads to an incorrect analytical result (an Undesired State), have a recovery plan. This involves recalculating results with a corrected or different database and documenting the discrepancy for future learning.

The relationship between these components and the necessary countermeasures is shown below:

Quantitative Data on Repository Errors

Table 1: Quantified Prevalence of Errors in NCBI Databases

| Database / Resource | Error Type | Quantified Prevalence | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCBI NR (Non-Redundant) | Taxonomic Misclassification | 2,238,230 proteins (7.6% of multi-taxa sequences) [1] | False positive/negative taxa detection; error propagation [1] |

| NCBI NR (95% clusters) | Taxonomic Misclassification | 3,689,089 clusters (4% of all clusters) [1] | Impacts cluster-based analyses and functional annotation [1] |

| NCBI GenBank | Contaminated Sequences | 2,161,746 sequences identified [2] | Detection of spurious organisms (e.g., turtle DNA in human gut) [2] |

| NCBI RefSeq | Contaminated Sequences | 114,035 sequences identified [2] | Reduced accuracy of curated "ground truth" [2] |

| NCBI RefSeq | Taxonomic Misannotation | ~1% of prokaryotic genomes [2] | Limits reliable identification in clinical/metagenomic settings [2] |

Table 2: Root Causes and Frequencies of Taxonomic Misannotation

| Root Cause | Description | Example | Frequency / Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| User Submission Error | Incorrect metadata provided by researcher during data deposition. | Submitting Glycine soja data as Glycine max [1]. | NCBI flags ~75 genome submissions/month for review [2]. |

| Sample Contamination | Impurities in the biological sample lead to foreign sequences. | Soil bacteria in a plant root sample [1]. | Human sequences contaminate 2,250 bacterial/archaeal genomes [1]. |

| Computational Error | Tool misannotation based on homology to existing erroneous sequences. | Propagation of an initial misclassification [1]. | Underlying cause for a significant portion of the 7.6% misclassified proteins [1]. |

| Limitations of Legacy ID | Inability of traditional methods to differentiate closely related species. | 16S rRNA cannot reliably differentiate E. coli and Shigella [2]. | Leads to technically inaccurate labels in databases [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Database Curation and Error Mitigation

| Tool / Resource | Function | Use Case in Error Management |

|---|---|---|

| BoaG / Hadoop Cluster [1] | A genomics-specific language and platform for large-scale data exploration. | Enables analysis of massive datasets like the entire NR database, which is not feasible with conventional tools. |

| VecScreen [1] | A tool recommended by NCBI to screen for vector contamination. | Used as a standard countermeasure to identify and remove common contaminant sequences. |

| Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) [2] | A metric to compute the genetic similarity between two genomes. | Detects taxonomic misannotation by identifying sequences that are outliers (e.g., below 95% ANI) for their assigned species. |

| MisPred / FixPred [1] | Tools that detect erroneous protein annotations based on violations of biological principles. | Identifies mispredicted protein sequences (e.g., violating domain integrity) in public databases. |

| Gold-Standard Type Material [2] | Trusted biological material deposited in multiple culture collections. | Serves as a reference for validating and correcting the taxonomic identity of misannotated sequences. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the most common error types in viral reference sequence databases, and how do they impact my analysis?

Errors in viral reference databases are pervasive and can significantly skew research findings. The most common issues include taxonomic mislabeling, where a sequence is assigned to the wrong species or genus, and various forms of sequence contamination, such as chimeric sequences (artificial fusion of two distinct sequences) and partitioned contamination (where contaminants are spread across different entries). These errors can lead to false positive identifications, false negative results, and imprecise taxonomic classifications, ultimately compromising the validity of your research, from outbreak tracking to phylogenetic studies [5].

FAQ 2: How can I identify and resolve taxonomic mislabeling in viral sequences?

Taxonomic mislabeling occurs when a sequence is assigned an incorrect taxonomic identity, often due to data entry errors or misidentification of the source material by the submitter [5].

Diagnosis:

- Unexpected Phylogenetic Placement: Your phylogenetic analysis shows sequences clustering with distantly related or unexpected viral groups.

- Inconsistent Metadata: Anomalies are discovered between the sequence's taxonomic label and its associated metadata (e.g., a "human adenovirus" sequence sourced from a plant).

- Failed Classification: Reference-based classifiers assign your query sequence to a different taxon than expected, or classification confidence is unusually low for a supposedly well-characterized virus.

Resolution Protocol:

- Cross-Reference with Type Material: Compare the sequence in question against sequences derived from type material or authoritative, curated strains [5].

- Perform Robust Phylogenetic Analysis: Use whole-genome or conserved core gene sequences to build phylogenetic trees. Mislabeled sequences will often appear as outliers within their assigned taxon [5].

- Leverage Taxonomic Tools: Utilize tools and databases that specialize in detecting taxonomic discordance. The NCBI Taxonomy database is continuously updated to reflect the latest ICTV standards, which can help resolve discrepancies [6].

FAQ 3: What steps should I take when I suspect a chimeric sequence or other contamination?

Sequence contamination, including chimeras, is a recognized and widespread issue in public databases. Chimeras are hybrid sequences formed from two or more parent sequences, often during sequencing or assembly [5].

Diagnosis:

- Inconsistent Coverage: A sudden, sharp drop in sequencing coverage in a specific region of the genome may indicate a chimera junction.

- Tool-Based Detection: Specialized software tools are designed to scan sequences and identify chimeric regions [5].

- Taxonomic Discordance: Different regions of the same contig or sequence are classified to divergent taxonomic groups with high confidence.

Resolution Protocol:

- Detection: Run your sequences through dedicated chimera detection tools [5].

- Validation & Removal: Manually inspect the flagged regions. For confirmed chimeras, the contaminated sequence should be removed from your analysis or the chimeric region trimmed if the remainder of the sequence is valid.

- Prevention: Implement stringent laboratory controls during sample processing and library preparation to minimize the creation of chimeras. Always vet sequences from public databases before inclusion in a custom reference set [5].

Error Type Reference Tables

Table 1: Common Viral Database Sequence Errors and Mitigation Strategies

| Error Type | Description | Potential Impact on Research | Recommended Mitigation Tools & Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Mislabeling [5] | Sequence is assigned an incorrect taxonomic identity. | False positive/negative detections; inaccurate phylogenetic trees; incorrect conclusions about viral diversity. | Phylogenetic analysis against type material; use of curated databases; tools for taxonomic discordance detection [5]. |

| Chimeric Sequence Contamination [5] | Artificial fusion of two or more parent sequences into a single sequence. | Inaccurate genome assemblies; erroneous gene predictions; invalid evolutionary inferences. | GUNC, CheckV, Conterminator [5]. |

| Partitioned Sequence Contamination [5] | Contaminating sequences are distributed across multiple database entries. | Inflated estimates of taxonomic diversity; misassignment of sequence reads. | BUSCO, CheckM, EukCC, compleasm [5]. |

| Poor Quality Reference Sequences [5] | Sequences with high fragmentation, low completeness, or other quality issues. | Reduced number of classified reads; lower classification accuracy; biased results. | Implement strict quality control (e.g., CheckM for completeness, fragmentation checks); use curated subsets like RefSeq [5]. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Error Identification

| Experiment / Analysis | Objective | Detailed Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Validation | To verify the taxonomic placement of a sequence and identify potential mislabeling. | 1. Sequence Selection: Extract the sequence of interest. Gather reference sequences from type material and representative genomes for the suspected and related taxa.2. Multiple Sequence Alignment: Use a tool like MAFFT or MUSCLE to align the sequences.3. Model Selection: Find the best-fit nucleotide substitution model using software like ModelTest-NG.4. Tree Construction: Infer a phylogenetic tree using maximum likelihood (RAxML, IQ-TREE) or Bayesian (MrBayes) methods.5. Interpretation: A mislabeled sequence will not cluster robustly with its named taxon but will instead group with its true relatives. |

| Chimera Detection | To identify artificial hybrid sequences within a dataset. | 1. Tool Selection: Choose a detection tool such as GUNC or CheckV [5].2. Input Preparation: Format your sequences (e.g., FASTA) according to the tool's requirements.3. Execution: Run the tool on your dataset. Each tool uses different algorithms (e.g., reference-based, de novo) to identify chimeric breaks.4. Manual Curation: Visually inspect the output, checking aligned regions and coverage plots for putative chimeras. Remove or trim confirmed chimeric sequences. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Workflow for Database Errors

Diagram 2: Sequence Contamination Identification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Viral Sequence Error Management

| Tool / Resource | Function | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| GUNC [5] | Chimera Detection | Identifies chimeric sequences in genomes by assessing taxonomic homogeneity. |

| CheckV [5] | Genome Quality Assessment | Evaluates the completeness and quality of viral genome sequences and identifies contaminant host regions. |

| BUSCO [5] | Contamination & Completeness | Assesses genome completeness based on universal single-copy orthologs; significant deviations can indicate contamination or poor quality. |

| NCBI Taxonomy [6] | Taxonomic Standardization | Provides a curated taxonomy used by public databases, updated to reflect ICTV rulings, helping to resolve naming and classification conflicts. |

| CheckM [5] | Quality Control (Prokaryotes) | Uses lineage-specific marker genes to estimate genome completeness and contamination in prokaryotic datasets. |

| Curated RefSeq | High-Quality Reference Set | A non-redundant, curated subset of NCBI sequences, generally of higher quality and with lower contamination rates than GenBank [5]. |

The Impact of Incomplete and Inaccurate Metadata on Downstream Analysis

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My downstream phylogenetic analysis produced unexpected results. How can I determine if incomplete metadata is the cause?

A: Unexpected results, such as low statistical support for clades or anomalous clustering of viral sequences, can often be traced to incomplete or inaccurate lineage metadata. To diagnose this:

- Perform Data Provenance Checks: Use your platform's lineage impact analysis feature to trace the upstream sources of your sequence data [7]. Verify that the source databases and original sample metadata are consistent with your assumptions.

- Audit Taxonomic Classifications: Cross-reference the species and genus classifications in your dataset with the latest International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) ratified proposals [8]. Misclassified sequences can severely skew analysis.

- Profile Metadata Completeness: Before analysis, run a script to calculate the completeness percentage for critical metadata fields (e.g., host organism, collection date, geographic location). Datasets with completeness below 85% for these key fields carry a high risk of analytical error.

Q2: After a schema change in our internal viral database, several automated genotyping workflows failed. What steps should we take?

A: This is a classic impact of incomplete technical metadata. To resolve and prevent future issues:

- Immediate Root Cause Analysis: Use active metadata management platforms to conduct a root cause analysis [9]. These systems can furnish comprehensive insights, helping you identify that the schema change altered a critical field used by the downstream workflows.

- Execute Downstream Impact Analysis: Utilize a lineage impact analysis tool to understand the complete set of downstream dependencies (e.g., scripts, dashboards, reports) affected by the changed data entity [7]. This allows you to proactively identify and notify owners of impacted assets.

- Implement Active Metadata Management: To prevent a recurrence, adopt active metadata management. With this, automated processes and real-time APIs ensure that every change to metadata triggers instant updates across the ecosystem [9]. This enables proactive detection of breaking changes before they cause failures.

Q3: What is the practical difference between data quality and data observability in the context of managing a viral sequence database?

A: These are complementary but distinct concepts crucial for database health [10].

- Data Quality is the goal—it describes the condition of your data against defined dimensions like accuracy, completeness, and consistency. For example, a requirement that "all submitted sequences must have a host organism metadata field populated" is a data quality standard.

- Data Observability is the method—it is the degree of visibility you have into your data's health and behavior in real-time. It uses continuous monitoring of metadata (like freshness, volume, and schema) to detect anomalies [10]. If the ingestion pipeline stops adding new sequences, an observability platform would alert you to this freshness issue before users notice.

Q4: Our team often applies "quick fixes" to metadata errors, but the same issues keep reoccurring. How can we break this cycle?

A: This indicates an over-reliance on reactive error management and a lack of error prevention strategies [11]. A balanced approach is needed:

- Shift from a pure Error Management Culture (EMC): While an EMC that encourages moving quickly and fixing problems later is agile, it can lead to error prevention processes that are "misapplied, informal or absent" [11].

- Institute Error Prevention Measures: Establish formal, standardized processes and controls for metadata entry and validation [11]. This includes implementing data quality rules (e.g., validating country names against a standard list) and using automated profiling tools to identify anomalies before data is integrated into critical systems [9].

- Foster Organizational Learning: Conduct post-mortem analyses of metadata errors to identify the root cause. Use this learning to update and strengthen your prevention measures, creating a positive feedback loop [11].

Quantitative Data on Data Quality Dimensions

The following table summarizes key dimensions of data quality that directly impact analytical reliability. Incomplete or inaccurate metadata directly undermines these dimensions [10].

Table 1: Intrinsic Data Quality Dimensions and Metadata Impact

| Dimension | Description | Consequence of Poor Metadata |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Does the data correctly represent the real-world object or event? | Inaccurate host or geographic metadata leads to incorrect ecological inferences. |

| Completeness | Are all necessary data and metadata records present? | Missing collection dates prevents analysis of viral evolutionary rates over time. |

| Consistency | Is the data uniform across different systems? | The same virus labeled with different names in different sources creates duplication and false diversity. |

| Freshness | Is the data up-to-date with the real world? | Outdated taxonomic information (e.g., not reflecting ICTV changes) misinforms phylogenetic models [8]. |

| Validity | Does the data conform to the specified business rules and formats? | Geographic location metadata that does not follow a standard format (e.g., "USA" vs. "United States") hinders grouping and filtering. |

Table 2: Extrinsic Data Quality Dimensions and Metadata Impact

| Dimension | Description | Consequence of Poor Metadata |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Does the data meet the needs of the current task? | Including environmental viruses in a human-pathogen study due to poor host metadata dilutes signal. |

| Timeliness | Is the data available when needed for use cases? | Delays in annotating and releasing sequence metadata slows down critical research during an outbreak. |

| Usability | Can the data be used in a low-friction manner? | Metadata stored in unstructured PDFs instead of queryable database fields makes analysis prohibitively laborious. |

| Reliability | Is the data regarded as true and credible? | A database with a known history of incomplete provenance metadata will not be trusted by the research community. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Metadata Impact on Machine Learning-based Host Prediction

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to predict virus hosts using machine learning and k-mer frequencies [12].

1. Objective: To quantify how incomplete or inaccurate taxonomic metadata in training data affects the performance of a model predicting whether a virus infects mammals, insects, or plants.

2. Materials:

- Dataset: Complete genome sequences of RNA viruses with confirmed hosts (e.g., from Virus-Host DB) [12].

- Software: Python with scikit-learn, lightgbm, and xgboost libraries.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Data Preparation & Feature Engineering:

- Step 2 - Create Controlled Metadata Scenarios:

- Scenario A (Control): Train and test the model using datasets where families and genera are correctly represented in both sets.

- Scenario B (Incomplete Taxonomy): Train the model on a dataset from which entire virus families have been excluded, then test on sequences from those excluded families. This simulates a knowledge gap in the database.

- Scenario C (Inaccurate Host): Introduce a known error rate (e.g., 15%) by randomly shuffling the host labels (mammal, insect, plant) in the training dataset to simulate incorrect host metadata.

- Step 3 - Model Training & Evaluation:

- For each scenario, train multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Gradient Boosting) [12].

- Evaluate model performance using weighted F1-scores across the three host classes. Compare the F1-scores from Scenarios B and C against the control (Scenario A) to quantify the degradation caused by poor metadata.

Protocol 2: Lineage Impact Analysis for Root Cause Investigation

1. Objective: To rapidly identify the upstream source of a data quality issue affecting downstream viral variant reports.

2. Materials:

- A data catalog or platform with lineage impact analysis capability (e.g., DataHub) [7].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Identify the Affected Entity: Locate the specific Dashboard, Chart, or Dataset that is showing erroneous or unexpected results.

- Step 2 - Execute Upstream Lineage Analysis:

- Navigate to the "Lineage" tab for the affected entity [7].

- Set the view to "Upstream" dependencies and increase the "Degree of Dependencies" to visualize the full data pipeline.

- Step 3 - Isolate the Root Cause:

- Use filters to isolate entities by type (e.g., "Table"), platform, or owner.

- Examine upstream datasets for recent schema changes, pipeline failures, or data freshness anomalies. The system provides visibility into dependencies, guiding impact analysis and change management [13].

- The root cause is often the most upstream entity showing a failure or recent change.

Visual Workflows

Diagram: Metadata Error Propagation Pathway

Diagram: Proactive Metadata Quality Management

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Viral Sequence Metadata Management

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Active Metadata Platform | Automates the collection, synchronization, and activation of metadata. Drives proactive data management [9]. | Provides real-time alerts on pipeline failures or schema changes that could corrupt viral sequence data before it affects downstream models. |

| Data Observability Tool | Provides continuous visibility into data health and behavior by monitoring logs, metrics, and lineage [10]. | Monitors statistical profiles of sequence data to detect sudden anomalies in data volume or content, indicating a potential ingestion error. |

| Lineage Impact Analysis | Visualizes and analyzes upstream and downstream dependencies of data assets [7]. | Used for root cause analysis to trace an erroneous variant call back to a specific problematic data source or processing step. |

| ICTV Taxonomy Reports | Provides the authoritative, ratified classification and nomenclature of viruses [8]. | Serves as the ground truth for validating and correcting taxonomic metadata in internal databases, ensuring phylogenetic accuracy. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers | Predicts host or other traits from viral genome k-mer frequencies [12]. | Can flag sequences where the predicted host strongly contradicts the recorded host metadata for manual review, identifying potential errors. |

The FAIR Guiding Principles—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—establish a framework for enhancing the utility and longevity of digital research assets [14]. For researchers managing viral database sequences and taxonomy, implementing FAIR principles directly addresses critical challenges in data error management, ensuring datasets remain discoverable and usable by both humans and computational systems amid rapidly expanding data volumes [15].

The core objective of FAIR is to optimize data reuse, with specific emphasis on machine-actionability—the capacity of computational systems to find, access, interoperate, and reuse data with minimal human intervention [14]. This is particularly relevant for viral sequence data, where accurate host prediction and classification rely on computational analysis of large datasets [12].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: How do FAIR principles specifically help with viral sequence error reduction?

FAIR principles combat viral sequence errors through enhanced metadata richness, persistent identifiers, and standardized vocabularies. These elements create an audit trail that helps identify discrepancies, standardize annotation practices across databases, and facilitate cross-referencing between datasets to flag inconsistencies [15] [16]. For example, the use of controlled vocabularies (Interoperability principle I2) ensures that a host organism is consistently labeled, reducing classification errors that complicate viral taxonomy research [16].

FAQ: We have a legacy viral sequence dataset. What's the first step to make it FAIR?

The initial step involves conducting a FAIRness assessment against the established sub-principles. The following table outlines key actions for this process [16]:

Table: Initial FAIRification Steps for a Legacy Viral Sequence Dataset

| FAIR Principle | Key Assessment Questions | Recommended Immediate Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Findability | Do sequences have persistent identifiers? Is metadata rich enough for discovery? | Register dataset in a repository for a DOI; create rich metadata file describing sequencing methods, host organism, collection date [17]. |

| Accessibility | How is the data retrieved? Is metadata preserved if data becomes unavailable? | Upload to a trusted repository with standard protocol; ensure metadata is stored separately from data [14]. |

| Interoperability | What formats are used? Are community standards applied? | Convert sequences to standard format (e.g., FASTA); use controlled terms for host species, tissue type [15]. |

| Reusability | Is the data usage license clear? Are provenance and experimental details documented? | Apply a clear usage license; document lab protocols, data processing steps, and software versions used [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common FAIR Implementation Challenges

- Problem: Inconsistent host organism identification in metadata.

- Solution: Adopt and use a single, authoritative taxonomy database (e.g., NCBI Taxonomy) for all host organism labels. This implements Interoperability sub-principle I2, which requires using FAIR vocabularies [16].

- Problem: Computational tools cannot process our data automatically.

- Problem: Dataset is not being discovered or cited by other researchers.

- Solution: Register your dataset in a domain-specific repository (e.g., Virosaurus, GenBank for sequences) and a general-purpose repository (e.g., Zenodo) to obtain a persistent identifier. This fulfills Findability sub-principles F1 and F4 [15].

- Problem: Difficulty integrating data from different viral studies.

- Solution: Use shared data models and standardized metadata schemas (e.g., MIxS from the Genomic Standards Consortium) for your domain. This directly implements Interoperability principles I1 and I3 [16].

Experimental Protocols for FAIRness Evaluation

This protocol provides a methodology to quantitatively assess the implementation of FAIR principles within a viral database, focusing on metrics relevant to sequence error management and host prediction research.

Protocol 1: Quantitative Assessment of FAIR Implementation in a Viral Database

1. Objective: To measure the adherence of a viral sequence database (e.g., Virus-Host DB) to the FAIR principles using a scorable checklist [16] [12].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Target viral sequence database (e.g., from Virus-Host DB, NCBI RefSeq).

- FAIR assessment checklist (see Table 1 below).

- Spreadsheet software for scoring.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Define the Scope. Identify the specific dataset or subset within the larger database to be evaluated.

- Step 2: Checklist Application. For each sub-principle in the checklist, score "1" for fully met, "0.5" for partially met, and "0" for not met. Gather evidence for each score.

- Step 3: Data Collection. Attempt to access data and metadata using the provided protocols and identifiers.

- Step 4: Interoperability Test. Try to integrate a sample of data with a standard bioinformatics workflow (e.g., a k-mer counting script for host prediction).

- Step 5: Reusability Audit. Check for the presence of a license, detailed provenance, and data creation protocols.

- Step 6: Analysis. Calculate a total FAIR score and scores for each letter (F, A, I, R). Identify weak areas for improvement.

Table 1: FAIR Principles Assessment Checklist for Viral Databases

| Principle | Sub-Principle Code | Metric for Viral Database Context | Score (0, 0.5, 1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Findability (F) | F1 | Data and metadata are assigned a globally unique and persistent identifier (e.g., DOI, accession number). | |

| F2 | Data is described with rich metadata (e.g., host health status, sequencing platform, assembly method). | ||

| F3 | Metadata clearly includes the identifier of the data it describes. | ||

| F4 | (Meta)data is registered in a searchable resource (e.g., domain-specific repository). | ||

| Accessibility (A) | A1 | (Meta)data are retrievable by their identifier via a standardized protocol (e.g., HTTPS, API). | |

| A1.1 | The protocol is open, free, and universally implementable. | ||

| A1.2 | The protocol allows for an authentication and authorization procedure, if necessary. | ||

| A2 | Metadata remains accessible, even if the underlying data is no longer available. | ||

| Interoperability (I) | I1 | (Meta)data uses a formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation (e.g., JSON-LD, RDF). | |

| I2 | (Meta)data uses FAIR-compliant vocabularies (e.g., NCBI Taxonomy, EDAM ontology, MeSH terms). | ||

| I3 | (Meta)data includes qualified references to other (meta)data (e.g., links to host organism database). | ||

| Reusability (R) | R1 | (Meta)data are richly described with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes. | |

| R1.1 | (Meta)data is released with a clear and accessible data usage license. | ||

| R1.2 | (Meta)data is associated with detailed provenance (e.g., sample collection, processing steps). | ||

| R1.3 | (Meta)data meets domain-relevant community standards. |

Protocol 2: Experimental Workflow for Evaluating the Impact of FAIR Data on Virus Host Prediction Models

This protocol uses machine learning to test the hypothesis that FAIRer data improves the performance and generalizability of models for predicting hosts from viral sequences [12].

1. Objective: To compare the performance of virus host prediction models trained on datasets with varying levels of FAIRness.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Viral Sequence Data: Curated sets of complete RNA virus genomes from a database like Virus-Host DB [12].

- Computing Environment: Python programming environment with scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM libraries.

- Feature Extraction Tools: Scripts for calculating k-mer frequencies (e.g., 4-mer frequencies).

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Curation and FAIRness Scoring. Assemble two datasets from Virus-Host DB: one with high-quality, well-annotated sequences (High-FAIR) and another with sparse metadata (Low-FAIR). Score each using the checklist from Protocol 1.

- Step 2: Feature Engineering. For all viral genomes, compute k-mer frequency features (e.g., k=4). This converts each genome into a numerical vector based on the frequency of all possible sub-sequences of length

k[12]. - Step 3: Model Training. For each dataset (High-FAIR and Low-FAIR), train multiple machine learning models (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest) to predict the host class (e.g., mammal, insect, plant).

- Step 4: Model Evaluation. Use a rigorous train-test split, such as the "non-overlapping genera" approach, where genera in the test set are entirely absent from the training set. This tests the model's ability to predict hosts for truly novel viruses [12].

- Step 5: Performance Comparison. Evaluate models using the weighted F1-score and compare the performance between models trained on High-FAIR vs. Low-FAIR data.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this experimental protocol:

Experimental Workflow for FAIR Data Impact

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for FAIR-Compliant Viral Taxonomy Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to FAIR Principles & Viral Research |

|---|---|---|

| CyVerse [18] | A scalable, cloud-based data management platform for large, complex datasets. | Provides the infrastructure for making data Accessible and Findable, handling massive datasets like the 300TB Precision Aging Network release. |

| Virus-Host DB [12] | A curated database of taxonomic links between viruses and their hosts. | Serves as a potential source of Interoperable data that uses standard taxonomies, useful for training host prediction models. |

| HALD Knowledge Graph [19] | A text-mined knowledge graph integrating entities and relations from biomedical literature. | Demonstrates advanced Findability and Interoperability by linking disparate data types (genes, diseases) using NLP, a model for linking viral and host data. |

| GitHub / Zenodo | Code repository and general-purpose data repository. | Findability, Accessibility, Reusability: GitHub hosts code; Zenodo provides a DOI for permanent storage, linking code and data for full provenance. |

| PubMed / PubTator [19] | Biomedical literature database with automated annotation tools. | Findability: Critical for discovering existing knowledge. PubTator helps extract entities for building structured, machine-readable (Interoperable) knowledge bases. |

| NCBI Taxonomy | Authoritative classification of organisms. | Interoperability: Using this standard vocabulary for host organisms ensures data can be integrated and understood across different systems. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) [12] | A machine learning algorithm effective for classification tasks. | Used for virus host prediction based on k-mer frequencies; performance is a metric for testing the Reusability and quality of underlying FAIR data. |

In the fields of virology, epidemiology, and drug development, reliance on accurate database sequences is paramount. Errors introduced at any stage—from sequence submission and annotation to clinical data entry—can propagate through the scientific ecosystem, leading to misguided research conclusions, flawed diagnostic assays, and inefficient therapeutic development. This technical support center outlines documented case studies and provides actionable troubleshooting guides to help researchers identify, mitigate, and prevent such errors within the context of viral database sequence error management taxonomy.

Documented Case Studies and Quantitative Error Analysis

Case Study: Misclassification in Viral Metagenomics

The Problem: A study evaluating taxonomic classification tools using a controlled Viral Mock Community (VMC) revealed that standard analysis methods could misclassify viral sequences. For instance, one standard approach missed a rotavirus constituent and generated misclassifications for adenoviruses, incorrectly labeling some contigs and failing to identify others [20].

The Impact: Such misclassification complicates the understanding of virome composition, which is critical for studies investigating viral associations with diseases, environmental health, or for biosurveillance. Inaccurate profiles can lead researchers to pursue false leads.

The Solution: The study found that the VirMAP tool, which uses a hybrid nucleotide and protein alignment approach, correctly identified all expected VMC constituents with high precision (F-score of 0.94), outperforming other methods, especially at lower sequencing coverages [20]. The quantitative comparison is summarized below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Taxonomic Classifiers on a Viral Mock Community

| Pipeline/Method | Precision | Recall | F-score | Key Issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VirMAP | 0.88 | 1.0 | 0.94 | Correctly identified all 7 expected viruses [20] |

| Standard Approach | N/A | Low | N/A | Missed rotavirus; misclassified adenovirus B [20] |

| FastViromeExplorer | High | Lower | N/A | Recall lowered by read count/taxonomic rank cutoffs [20] |

| Read Classifying Pipelines | Variable | Variable | Generally Lower | Suffer from aberrant database alignments [20] |

Case Study: Clinical Research Database Entry Errors

The Problem: An analysis of several clinical oncology research databases revealed alarmingly high error rates. When the same 1,006 patient records were entered into two separate databases, discrepancy rates for demographic data fields (e.g., date of birth, medical record number) ranged from 2.3% to 5.2%. Discrepancies for treatment-related data (e.g., first treatment date) were significantly worse, ranging from 10.0% to 26.9% [21].

The Impact: These errors directly affect the reliability of research outcomes. For example, an analysis of two independently entered datasets on tumor recurrence in 133 patients showed statistically significant differences in the calculated "time to recurrence" [21]. This could directly mislead conclusions about treatment efficacy.

The Solution: The study found that error detection based solely on "impossible value" constraints (e.g., a radiation treatment date on a Sunday) caught fewer than 2% of errors. The most effective method was double-entry, where two individuals independently enter the same data, with subsequent reconciliation of discrepancies [21].

Table 2: Clinical Data Entry Error Rates and Detection Methods

| Error Category | Field Example | Error Rate | Ineffective Detection Method | Effective Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Data | Date of Birth, MRN | 2.3% - 5.2% | Constraint-based alarms | Double-data entry with reconciliation [21] |

| Treatment Data | First Treatment Date | Up to 26.9% | Checking for "impossible" Sunday dates | Double-data entry with reconciliation [21] |

| Internal Consistency | Vital Status vs. Relapse | 8.4% - 10.6% | N/A | Logic checks between related fields [21] |

Case Study: Sequence Annotation and Submission Pitfalls

The Problem: The submission of uncultivated virus genomes (UViGs) to public databases like GenBank carries inherent risks of error. A common issue is the preemptive or incorrect use of taxonomic names in the ISOLATE field of a record. Since virus taxonomy is dynamic, an isolate named "novel flavivirus 5" may later be reclassified outside of the Flaviviridae family, creating persistent confusion [22].

The Impact: Misannotated sequences in public databases become part of the reference set used by other researchers for sequence comparison, taxonomy, and primer/probe design, thereby propagating the error and compromising all downstream analyses that rely on that record.

The Solution: Adherence to International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC) and International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) guidelines is critical. For a novel sequence, the ORGANISM field should use the format "<lowest fitting taxon> sp." (e.g., "Herelleviridae sp."), while the ISOLATE field should contain a unique, taxonomy-free identifier (e.g., "VirusX-contig45") [22].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Our metagenomic analysis produced a novel viral contig. How should we submit it to a public database to avoid common annotation errors?

Answer: Follow standardized submission guidelines to ensure long-term accuracy and utility.

- Choose the Right Database: Submit the annotated genome sequence to an INSDC database (GenBank, ENA, or DDBJ) [22].

- Use Correct Naming Conventions:

- Provide Rich Metadata: Include critical metadata using MIUViG (Minimum Information about an Uncultivated Virus Genome) and MIxS (Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence) checklists, detailing genome quality, assembly methods, and environmental source [22].

- Indicate Genome Completeness: Use the "complete genome" tag only if genome termini have been experimentally verified (e.g., by RACE). Otherwise, describe it as "coding-complete" if all open reading frames are fully sequenced [22].

FAQ 2: We are seeing inconsistent viral taxonomic assignments from the same dataset when using different bioinformatics tools. How can we troubleshoot this?

Answer: Inconsistent results often stem from the underlying algorithms and databases used by different tools.

- Benchmark with Mock Communities: If possible, process a published mock community dataset with known constituents using your tools. This will reveal biases and error rates specific to each pipeline [20].

- Investigate Underlying Method: Understand if the tool is based on read mapping, contig mapping, or a hybrid approach. Contig-based classifiers generally have higher precision but may miss low-abundance viruses, while read-based classifiers can suffer from false positives due to short, non-specific alignments [20].

- Validate with a Hybrid Approach: For critical findings, use a tiered approach. For example, use a sensitive read-based classifier for initial discovery, followed by confirmation with a more precise contig-based classifier or a tool like VirMAP that uses both nucleotide and protein-level information [20].

- Check Database Versions: Ensure you are using the same, most recent version of viral reference databases across all tools to eliminate discrepancies caused by outdated taxonomy.

FAQ 3: What is the most effective way to minimize errors in our manually curated clinical research database?

Answer: Proactive error prevention is more effective than post-hoc detection.

- Implement Double-Data Entry: The highest data integrity is achieved by having two trained individuals independently enter the same set of records, followed by a systematic reconciliation of all discrepancies. This method has been shown to catch errors that other methods miss [21].

- Design Smart Electronic Data Capture (EDC) Systems: Incorporate real-time validation checks that go beyond simple range checks. Include:

- Audit and Feedback: Conduct regular, random audits of data entries and provide feedback to the data entry team to correct systematic misunderstandings or common mistakes.

Experimental Protocols for Error Detection

Protocol: Validating Viral Taxonomic Classification

Purpose: To confirm the taxonomic assignment of a viral genome sequence derived from metagenomic data using a robust, multi-layered approach.

Methodology:

- Assembly Quality Control: Assemble reads into contigs and assess for chimerism by evaluating the distribution of mapped reads and read pairs. Check for terminal redundancy as evidence of genome termini [22].

- Tiered Classification: Run the assembled contigs through a classification pipeline that uses a combination of:

- Nucleotide Alignment (BLASTn): For identifying highly similar sequences.

- Protein Alignment (BLASTx/tBLASTn): For detecting more divergent viruses where nucleotide similarity is low but protein sequences are conserved [20].

- Consensus and Confidence Scoring: Generate a consensus taxonomy from the different methods. Employ a bits-per-base or similar scoring system to assign confidence to the classification, setting a minimum threshold for acceptance [20].

- Comparative Analysis: Validate your result by comparing the output of multiple dedicated taxonomic classifiers (e.g., VirMAP, Kaiju, VPF-Class) on your dataset [23] [20].

Protocol: Implementing a Double-Data Entry System

Purpose: To minimize data entry errors in clinical or manually curated research databases.

Methodology:

- First Entry: Have Technician A enter the data from the source document (e.g., electronic medical record, paper form) into the database.

- Second Entry: Have Technician B, blinded to the entries made by Technician A, enter the same set of source documents into a temporary, parallel database.

- Automated Reconciliation: Use a software script or database function to compare the two datasets field-by-field. All discrepancies are automatically flagged in a discrepancy report.

- Adjudication: A third, senior researcher or data manager reviews the original source document against the discrepancy report and determines the correct value. The final, adjudicated value is then entered into the master research database.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Viral Sequence Error Management

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Mock Communities | Gold-standard positive controls for benchmarking the accuracy and precision of wet-lab and computational workflows. | Published communities from BioProjects PRJNA431646 [20] and PRJNA319556 [20]. |

| Hybrid Taxonomic Classifiers | Bioinformatics tools that combine nucleotide and protein alignment strategies for more accurate classification of divergent viruses. | VirMAP [20], VirusTaxo [23]. |

| INSDC Submission Portals | Official channels for submitting annotated viral genome sequences, ensuring persistence, accessibility, and proper taxonomy linkage. | NCBI's BankIt/table2asn, ENA's Webin, DDBJ's NSSS [22]. |

| MIUViG/MIxS Checklists | Standardized metadata checklists for reporting genomic and environmental source data, promoting reproducibility and data reuse. | MIUViG standards for genome quality, annotation, and host prediction [22]. |

| Double-Data Entry Workflow | A process, not a reagent, but essential for creating high-fidelity manually curated datasets for clinical or phenotypic correlation. | Implementation of dual entry with reconciliation as described in clinical error analyses [21]. |

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Accurate Taxonomic Classification and Host Prediction

What is the primary limitation of traditional, homology-based methods like BLAST for virus host prediction?

Traditional methods like BLAST rely on sequence similarity to identify hosts. A significant drawback is their inability to predict hosts for novel or highly divergent viruses that share little to no sequence similarity with any known virus in reference databases. This results in a large proportion of metagenomic sequences being classified as "unknown" [24]. Machine learning (ML) approaches overcome this by using alignment-free features, such as k-mer compositions, which can capture subtle host-specific signals even in the absence of direct sequence homology [25].

How can machine learning predict a virus's host just from its genome sequence?

Over time, the co-evolutionary relationship between a virus and its host embeds a host-specific signal in the virus's genome. This occurs because viruses must adapt to their host's cellular environment, including its nucleotide bias, codon usage, and immune system. Machine learning models are trained to recognize these patterns [25]. They use features derived from the viral genome sequence—such as short k-mer frequencies, codon usage, or amino acid properties—to learn the association between a virus's genomic "fingerprint" and its host [12] [25].

Within the context of viral database sequence error management, what is an "Error Taxonomy"?

An Error Taxonomy is a systematic classification framework that categorizes different types of errors, failures, and exceptions. In the context of viral sequence analysis, this can help researchers systematically identify, understand, and resolve issues that may arise during the host prediction workflow. It classifies problems by their cause, severity, and complexity, enabling targeted solutions rather than ad-hoc troubleshooting [26]. Common categories in this field might include sequence quality errors (e.g., sequencing artifacts, contamination), database-related errors (e.g., misannotated reference sequences, outdated host links), and model application errors (e.g., using a model on a virus type it was not trained for).

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing Poor Model Performance on Novel Viruses

Problem: Your ML model performs well on viruses related to those in your training set but fails to generalize to novel or evolutionarily distant viruses.

Solution: This is often a dataset composition issue. To create a model that robustly predicts hosts for unknown viruses, the training and testing datasets must be split in a way that prevents data leakage from closely related sequences.

Methodology: Implement a Phylogenetically-Aware Train-Test Split

Do not randomly split your genome sequences into training and test sets. Instead, partition them based on taxonomic groups to simulate a real-world scenario where the host of a completely novel genus or family needs to be predicted [12].

- Data Collection: Obtain complete genome sequences from a curated database like the Virus-Host Database.

- Data Filtering: Exclude genomes that are overly similar (e.g., >92% identity) to reduce bias from overrepresented families. Also exclude arboviruses with multiple hosts, as they complicate the labeling process [12].

- Dataset Partitioning: Create different train-test splits for evaluating model generalization [12]:

- Non-overlapping Genera: All genera in the test dataset are completely absent from the training dataset.

- Non-overlapping Families: All families in the test dataset are completely absent from the training dataset.

- Performance Evaluation: Train your model on the training set and evaluate it on the held-out test set. Use metrics like the weighted F1-score to account for class imbalance. A study using this method achieved a median weighted F1-score of 0.79 for predicting hosts of unknown virus genera, a significant improvement over baseline methods [12].

Guide: Handling Short/Partial Viral Sequences from Metagenomics

Problem: Metagenomic studies often produce short sequence reads or contigs, and models trained on full viral genomes perform poorly on these fragments.

Solution: Train your model using short sequence fragments that mimic the actual output of metagenomic sequencing, rather than using complete genomes.

Methodology: Training on Simulated Metagenomic Fragments

- Fragment the Genomes: Take the complete virus genomes from your training set and computationally break them down into non-overlapping subsequences of a defined length (e.g., 400 or 800 nucleotides) [12].

- Create a Balanced Fragment Set: To avoid over-representing longer genomes, randomly select a fixed number of fragments (e.g., two) from each genome for training [12].

- Train on Fragments: Use these short fragments, with their corresponding host labels, to train the ML model. This approach consistently improves prediction quality on real metagenomic data because the model learns to recognize host-specific signals from short sequence stretches [12].

Guide: Selecting the Right Features for Host Prediction

Problem: You are unsure which features to extract from your viral genomes to train the most effective host prediction model.

Solution: The optimal feature type can depend on the specific prediction task. Empirical evidence suggests that simple, short k-mers from nucleotide sequences are highly effective and often outperform more complex features.

Methodology: Comparative Feature Evaluation

Research indicates that for RNA viruses infecting mammals, insects, and plants, using simple 4-mer (tetranucleotide) frequencies from the nucleotide sequence with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier yielded superior results for predicting hosts of unknown genera [12]. The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies on feature performance.

Table: Comparison of Features for Virus Host Prediction with Machine Learning

| Feature Type | Description | Reported Performance | Use Case & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide k-mers [12] [25] | Frequencies of short nucleotide sequences of length k. | Median weighted F1-score of 0.79 for 4-mers on novel genera [12]. | Simple, fast to compute. Predictive power generally improves with longer k (e.g., k=4 to k=9) [25]. |

| Amino Acid k-mers [25] | Frequencies of short amino acid sequences from translated coding regions. | Consistently predictive of host taxonomy [25]. | Captures signals from protein-level interactions. Performance improves with longer k (e.g., k=1 to k=4) [25]. |

| Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) [24] | Normalized frequency of using specific synonymous codons. | Area under ROC curve of 0.79 for virus vs. non-virus classification [24]. | Useful for tasks like distinguishing viral from host sequences in metagenomic data. |

| Protein Domains [25] | Predicted functional/structural subunits of viral proteins. | Contains complementary predictive signal [25]. | Reflects functional adaptations to the host. Can be combined with k-mer features for improved accuracy [25]. |

Key Takeaway: While all levels of genome representation are predictive, starting with nucleotide 4-mer frequencies is a robust and efficient approach for host prediction tasks [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which machine learning algorithm is best for virus host prediction? There is no single "best" algorithm, as performance can depend on the dataset and task. However, studies have consistently shown that Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and Gradient Boosting Machines (e.g., XGBoost) are among the top performers [12] [27] [28]. One study found SVM with a linear kernel performed best with 4-mer features, while RF and XGBoost were top performers in other tasks involving virus-selective drug prediction [12] [28]. It is recommended to test multiple algorithms.

Q2: My model has high accuracy but I suspect it's learning the wrong thing. What's happening? This could be a sign that your model is learning the taxonomic relationships between viruses rather than the host-specific signals. If your training data contains multiple viruses from the same family that all infect the same host, the model may learn to recognize the virus family instead of the true host-associated genomic features. This is why using a phylogenetically-aware train-test split (see Troubleshooting Guide 2.1) is critical for a realistic evaluation [12] [25].

Q3: Can these methods predict hosts for DNA viruses and bacteriophages? Yes, the underlying principles apply across virus types. The host-specific signals driven by co-evolution and adaptation are present in DNA viruses as well. For bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria), machine learning approaches are similarly employed, using features like k-mer compositions to predict bacterial hosts, and are considered a key in-silico method in phage research [25] [29].

Q4: How do I manage errors from using incomplete or misannotated viral databases? This is where an Error Taxonomy can guide your workflow. Implement a pre-processing checklist:

- Sequence Quality Control: Filter out sequences with excessive ambiguous bases (N's) or that are too short.

- Database Versioning: Always record the version of the database (e.g., Virus-Host DB, RefSeq) used for training. Errors in the reference data will propagate into your model.

- Label Verification: Manually audit a subset of host labels, especially for viruses that are known to have complex or multiple host relationships. This helps mitigate errors stemming from incorrect or outdated database annotations.

Visual Workflows & Diagrams

Virus Host Prediction ML Workflow

Error Taxonomy in Host Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for ML-Based Virus Host Prediction

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Virus-Host Database | Provides the essential labeled data (virus genome + known host) for training and testing models. | The Virus-Host Database is a widely used, curated resource that links viruses to their hosts based on NCBI/RefSeq and EBI data [12] [25]. |

| Sequence Feature Extraction Tools | Software or custom scripts to convert raw genome sequences into numerical feature vectors. | Python libraries like Biopython can be used to compute k-mer frequencies and Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) [24]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Pre-built implementations of ML algorithms for model training, evaluation, and hyperparameter tuning. | scikit-learn (for RF, SVM) and XGBoost/LightGBM (for gradient boosting) in Python are standard [12] [27]. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis Software | Tools to assess evolutionary relationships between viruses, crucial for creating robust train-test splits. | Tools like CD-HIT can be used to remove highly similar sequences and avoid overfitting [24]. |

| Metagenomic Assembly Pipeline | For processing raw sequencing reads from environmental samples into contigs for host prediction. | Pipelines often combine tools like Trinity, SOAPdenovo, or IDBA-UD for assembly, followed by BLAST for initial classification [24]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What is a k-mer and how is it used in feature representation for machine learning?

A k-mer is a contiguous subsequence of length k extracted from a longer biological sequence, such as DNA, RNA, or a protein [30]. In machine learning, k-mers serve as fundamental units for transforming complex, variable-length sequences into a structured, fixed-length feature representation suitable for model ingestion [31]. This process involves breaking down each sequence in a dataset into all its possible overlapping k-mers of a chosen length. The resulting k-mers are then counted and their frequencies are used to create a numerical feature vector for each sequence. This feature vector acts as a "signature" that captures the sequence's compositional properties, enabling the application of standard ML algorithms for tasks like classification, clustering, and anomaly detection [31] [30].

FAQ 2: How do I choose the optimal k-mer size for my project?

The choice of k is critical and involves a trade-off between specificity and computational tractability. The table below summarizes the key considerations:

Table 1: Guidelines for Selecting K-mer Size

| K-mer Size | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small k (e.g., 3-7) | - Lower computational memory and time [31]- Higher probability of k-mer overlap, aiding assembly and comparison [30] | - Lower specificity; may not uniquely represent sequences [31]- Higher rate of false positives in matching [32]- Cannot resolve small repeats [30] | - Rapid metagenomic profiling [32]- Initial, broad-scale sequence comparisons |

| Large k (e.g., 11-15) | - High specificity; better discrimination between sequences [31]- Reduced ambiguity in genome assembly [30] | - Exponentially larger feature space (4k for DNA) [31]- Sparse k-mer counts, leading to overfitting [31]- Higher chance of including sequencing errors [31] | - Precise pathogen detection [31]- Distinguishing between highly similar genomes or genes |

Troubleshooting Guide: If your model is suffering from poor performance, consider adjusting k. If you suspect low specificity is causing false matches, gradually increase k. Conversely, if the model is slow and the feature matrix is too sparse, try reducing k. For a balanced approach, some tools use gapped k-mers to maintain longer context without the computational blow-up [31].

FAQ 3: Our ML model is not generalizing well on viral sequence data. Could k-mer feature representation be a factor?

Yes, this is a common challenge, especially with k-mers. The issues and solutions are:

- Problem: Overfitting to Sparse Features. With long k-mers, the feature space becomes vast, and each k-mer may appear in very few samples. The model may then "memorize" these rare k-mers instead of learning generalizable patterns [31].

Solution: Use smaller k-values or dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA on the k-mer frequency matrix. Alternatively, employ

minimizersorsyncmers, which are subsampled representations of k-mers that reduce memory and runtime while preserving accuracy [31].Problem: Evolutionary Divergence and Database Errors. Your training data, based on a specific version of a taxonomic database (e.g., ICTV), may contain k-mer profiles that become obsolete as the database is updated with renamed taxa or new viral sequences. Furthermore, gene prediction errors in reference databases can propagate incorrect k-mers [33] [34].

- Solution: Implement a flexible k-mer database system that can be easily updated with new taxonomic releases. For error mitigation, incorporate error-correction methods for your raw sequencing reads and use multiple, high-quality reference databases to cross-validate the k-mers used for training [35] [34].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for managing k-mer databases to minimize errors?

Managing k-mer databases effectively is key to reliable results.

- Strategy 1: Use Efficient, Scalable Storage. Leverage database engines optimized for k-mer storage and retrieval. For example, kAAmer uses a Log-Structured Merge-tree (LSM-tree) Key-Value store, which is highly efficient for SSD drives and supports high-throughput querying, making it suitable for hosting as a remote microservice [32].

- Strategy 2: Incorporate Rich Annotations. Beyond the k-mers themselves, store comprehensive metadata about the source sequences (e.g., taxonomic lineage, protein function). This enriches downstream analysis and helps in troubleshooting and filtering results [32].

- Strategy 3: Implement Version Control. Given that reference taxonomies like the ICTV are updated frequently, maintain a system that tracks the version of the taxonomy used to build the k-mer database. Tools like ICTVdump can help automate the downloading of sequences and metadata for specific ICTV releases [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Custom K-mer Database for Viral Protein Identification

This protocol is based on the design of the kAAmer database engine for efficient protein identification [32].

1. Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for K-mer Database Construction

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Badger Key-Value Store | An efficient Go-language implementation of a disk-based storage engine, optimized for solid-state drives (SSDs). It forms the backbone of the database [32]. |

| Sequence Dataset | A collection of protein sequences in FASTA format from sources like UniProt or RefSeq. This is the raw data for k-merization [32]. |

| Protocol Buffers | A method for serializing structured data (protobuf). Used to efficiently encode and store protein annotations within the database [32]. |

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Data Acquisition. Use a tool like ICTVdump to download a consistent set of viral nucleotide or protein sequences and their associated metadata (e.g., taxonomic lineage) from a specific release of a reference database [33].

- Step 2: K-merization. Process each sequence to extract all possible overlapping amino acid k-mers of a fixed length (e.g., 7-mers). The fixed size allows for efficient storage and indexing [32].

- Step 3: Database Construction. Populate three interconnected key-value (KV) stores:

- K-mer Store: Keys are the individual k-mers. Values are pointers to entries in the combination store.

- Combination Store: Keys are the pointers from the k-mer store. Values are lists of protein identifiers that contain a given combination of k-mers.

- Protein Store: Keys are protein identifiers. Values are rich annotations (serialized via Protocol Buffers) for each protein, such as its full sequence, taxonomic ID, and functional description [32].

The workflow for this database construction is outlined below.

Protocol 2: K-mer-Based Protein Identification and Benchmarking

This protocol details how to use a k-mer database for identification and how to rigorously benchmark its performance against other tools [32].

1. Methodology

- Step 1: Query Processing. For a given query protein sequence, decompose it into its constituent k-mers (the same

kused to build the database). - Step 2: Database Lookup. For each k-mer in the query, perform a lookup in the K-mer Store and then the Combination Store to retrieve all protein targets in the database that share at least one k-mer with the query.

- Step 3: Scoring and Ranking. Score the matches between the query and each target. A simple but effective scoring metric is the count of shared k-mers. The targets can then be ranked based on this score. To improve accuracy, this alignment-free step can be optionally followed by a local alignment step for the top hits [32].

- Step 4: Benchmarking. Compare your k-mer-based method against established alignment tools like BLAST, DIAMOND, and Ghostz.

- Sensitivity Benchmark: Use a dataset with known positive and negative matches (e.g., protein families from ECOD) to plot a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. This evaluates the tool's ability to identify true positives while minimizing false positives [32].

- Speed Benchmark: Execute all tools on the same query dataset of varying sizes (e.g., from 1 to 50,000 proteins) and measure the wall-clock execution time. This highlights the trade-off between sensitivity and computational efficiency [32].

The logical flow of the identification and benchmarking process is visualized in the following diagram.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is CHEER, and what specific problem does it solve in viral metagenomics? CHEER (HierarCHical taxonomic classification for viral mEtagEnomic data via deep leaRning) is a novel deep learning model designed for read-level taxonomic classification of viral metagenomic data. It specifically addresses the challenge of assigning higher-rank taxonomic labels (from order to genus) to short sequencing reads originating from new, previously unsequenced viral species, a task for which traditional alignment-based methods are often unsuitable [36].

Q2: How does CHEER's approach differ from traditional alignment-based methods? Unlike alignment-based tools that rely on nucleotide-level homology search, CHEER uses an alignment-free, composition-based approach. It combines k-mer embedding-based encoding with a hierarchically organized Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) structure to learn abstract features for classification, enabling it to recognize new species from a new genus without prior sequence similarity [36].

Q3: Can CHEER distinguish viral from non-viral sequences in a sample? Yes. CHEER incorporates a carefully trained rejection layer as its top layer, which acts as a filter to reject non-viral reads (e.g., host genome contamination or other microbes) before the hierarchical classification process begins [36].

Q4: What are the key performance advantages of CHEER? Tests on both simulated and real sequencing data show that CHEER achieves higher accuracy than popular alignment-based and alignment-free taxonomic assignment tools. Its hierarchical design and use of k-mer embedding contribute to this improved classification performance [36].

Q5: Where can I find the CHEER software? The source code, scripts, and pre-trained parameters for CHEER are available on GitHub: https://github.com/KennthShang/CHEER [36].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model Performance | Model performance is significantly worse than expected or reported [37]. | 1. Start Simple: Use a simpler model architecture or a smaller subset of your data to establish a baseline and increase iteration speed [37].2. Overfit a Single Batch: Try to drive the training error on a single batch of data close to zero. This heuristic can catch a large number of implementation bugs [37]. |

| Model error oscillates during training. | Lower the learning rate and inspect the data for issues like incorrectly shuffled labels [37]. | |

| Model error plateaus. | Increase the learning rate, temporarily remove regularization, and inspect the loss function and data pipeline for correctness [37]. | |

| Implementation & Code | The program crashes or fails to run, often with shape mismatch or tensor casting issues. | Step through your model creation and inference step-by-step in a debugger, meticulously checking the shapes and data types of all tensors [37]. |

Encounter inf or NaN (numerical instability) in outputs. |

This is often caused by exponent, log, or division operations. Use off-the-shelf, well-tested components (e.g., from Keras) and built-in functions instead of implementing the math yourself [37]. | |

| Data-Related Issues | Poor performance due to dataset construction. | Check for common dataset issues: insufficient examples, noisy labels, imbalanced classes, or a mismatch between the distributions of your training and test sets [37]. |

| Pre-processing inputs incorrectly. | Ensure inputs are normalized correctly (e.g., subtracting mean, dividing by variance). Avoid excessive data augmentation at the initial stages [37]. |

Performance Tuning and Validation Protocol

To systematically evaluate and improve your CHEER model, follow this experimental validation protocol. The table below outlines key metrics and steps for benchmarking.

| Protocol Step | Description | Key Parameters & Metrics to Document |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline Establishment | Compare CHEER's performance against known baselines. | - Simple Baselines: e.g., linear regression or the average of outputs to ensure the model is learning [37].- Published Results: from the original CHEER paper or other taxonomic classifiers on a similar dataset [36]. |

| 2. Data Quality Control | Ensure the input data is suitable for the model. | - Read Length: Confirm reads are within the expected size range for viral metagenomics.- Sequence Quality: Check for per-base sequencing quality scores.- Composition: Verify the absence of excessive adapter or host contamination. |

| 3. Model Validation | Assess the model's predictive accuracy and robustness. | - Accuracy: Overall correctness of taxonomic assignments [36].- Hierarchical Precision/Recall: Measure performance at each taxonomic level (Order, Family, Genus).- Comparison to Alternatives: Benchmark against tools like Phymm, NBC, or protein-based homology search (BLASTx) [36]. |

| 4. Runtime & Resource Profiling | Evaluate computational efficiency, especially for large datasets. | - Processing Speed: Time to classify a set number of reads.- Memory Usage: Peak RAM/VRAM consumption during inference. |

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core hierarchical classification workflow of CHEER, which processes viral metagenomic reads from input to genus-level assignment.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key computational tools and resources essential for research in viral taxonomic classification, providing alternatives and context for CHEER.

| Tool/Resource Name | Brief Function/Description | Relevance to CHEER & Viral Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|

| CHEER | A hierarchical CNN-based classifier for assigning taxonomic labels to reads from new viral species [36]. | The primary tool of focus; uses k-mer embeddings and a top-down tree of classifiers. |

| Phymm & PhymmBL | Alignment-free metagenomic classifiers using interpolated Markov models (IMMs) [36]. | Predecessors in alignment-free classification; useful for performance comparison. |

| VIRIDIC | Alignment-based tool for calculating virus intergenomic similarities, recommended by the ICTV for bacteriophage species/genus delineation [38]. | Represents the alignment-based approach; a benchmark for accuracy on species/genus thresholds. |

| Vclust | An ultrafast, alignment-based tool for clustering viral genomes into vOTUs based on ANI, compliant with ICTV/MIUViG standards [38]. | A state-of-the-art tool for post-discovery clustering and dereplication; complements CHEER's classification. |

| ICTV Dump Tools | Scripts (e.g., ICTVdump from the Virgo publication) to download sequences and metadata from specific ICTV releases [33]. | Crucial for obtaining the most current and version-controlled taxonomic labels for training and evaluation. |