Navigating the Viral Phylogenetics Toolbox: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of viral phylogenetic analysis tools, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Navigating the Viral Phylogenetics Toolbox: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of viral phylogenetic analysis tools, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques. By synthesizing current software capabilities and best practices, this guide aims to empower users in selecting and applying the right tools for studies on viral evolution, outbreak tracking, and therapeutic target identification.

Understanding Viral Phylogenetics: Core Principles and Essential Tools

Defining Phylogenetic Trees and Their Role in Viral Research

Phylogenetic trees are diagrams that represent the evolutionary relationships among organisms, genes, or viruses based on their genetic similarities and differences [1] [2]. In viral research, they are indispensable for classifying new viruses, understanding their evolution, tracking the spread of outbreaks, and informing the development of vaccines and therapies [1] [3]. By analyzing genetic sequences, researchers can reconstruct these trees to visualize how different viral strains are related and trace the origins of new infections.

Key Computational Tools for Viral Phylogenetic Analysis

The field of viral phylogenetics relies on a suite of bioinformatics tools for tree construction and analysis. The table below summarizes some prominent software and libraries, highlighting their primary applications and methodologies.

Table 1: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Viral Phylogenetic Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Application | Methodology / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| PhyloTune [4] | Accelerating phylogenetic updates with new sequence data | Uses a pre-trained DNA language model (DNABERT) to identify the taxonomic unit of a new sequence and extract informative regions for targeted subtree updates. |

| FoldTree [5] | Resolving deep evolutionary relationships | Leverages artificial intelligence-based protein structure predictions and structural alignment to infer trees, outperforming sequence-only methods over long evolutionary timescales. |

| RAxML [1] | General phylogenetic tree inference | A widely used tool for maximum likelihood-based tree construction, which evaluates multiple possible trees under an evolutionary model to select the best one. |

| Phylo-rs [6] | Large-scale phylogenetic analysis & library development | A high-performance, memory-safe library written in Rust, enabling efficient tree comparisons, simulations, and edit operations on large datasets. |

| PhyloVAE [7] | Representation learning & generative modeling of tree topologies | An unsupervised deep learning framework that learns informative latent space representations of tree topologies, enabling visualization and clustering of tree samples. |

| MEGA [1] | Comprehensive molecular evolutionary genetics analysis | An integrated software suite with tools for multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction using various methods, including maximum likelihood and neighbor-joining. |

| BEAST/ MrBayes [1] | Bayesian phylogenetic inference | Software that uses Bayesian inference and Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to estimate phylogenetic trees, incorporating evolutionary models and providing posterior distributions. |

Comparative Performance of Phylogenetic Methods

Different phylogenetic approaches make trade-offs between computational efficiency and accuracy. The following table summarizes experimental data from recent studies comparing novel and traditional methods.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Phylogenetic Methods

| Method | Dataset / Context | Reported Performance | Key Comparative Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| PhyloTune [4] | Simulated datasets; Plant (Embryophyta) & microbial (Bordetella) datasets | Accuracy: Near-identical topology to full-tree methods for smaller datasets (n=20, 40 sequences); minor Robinson-Foulds (RF) distance increase for larger datasets (0.021-0.031 for n=60-100).Speed: Subtree update time was relatively insensitive to total sequence count; using high-attention regions reduced computational time by 14.3% to 30.3% compared to using full-length sequences. | Successfully balances accuracy and efficiency by updating only relevant subtrees, demonstrating a modest trade-off in topological accuracy for substantial gains in speed. |

| FoldTree [5] | Protein families across CATH database (divergent sequences) | Accuracy: Outperformed state-of-the-art sequence-based methods, achieving a higher Taxonomic Congruence Score (TCS). A larger proportion of trees built with FoldTree were top-ranked in congruence with known taxonomy. | Structure-informed phylogenetics is particularly powerful for analyzing divergent sequences where sequence-based signal is saturated, enabling the resolution of deeper evolutionary relationships. |

| Phylo-rs [6] | Scalability analysis vs. Dendropy, TreeSwift, Gotree, etc. | Speed: Performed comparably or better on key algorithms (Robinson-Foulds metric, tree traversals, simulations).Memory: Demonstrated high memory efficiency due to Rust's ownership model and avoidance of deep copies. | Provides a foundation for developing high-performance phylogenetic software, offering advantages in runtime and memory safety for large-scale analyses. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a deeper understanding of the compared methodologies, here are the detailed experimental protocols for two key approaches.

Protocol: Accelerated Phylogenetic Updates with PhyloTune

This protocol is based on the PhyloTune method for efficiently integrating new viral sequences into an existing reference tree [4].

- Objective: To rapidly and accurately place a newly collected viral sequence into an existing phylogenetic tree by identifying its smallest taxonomic unit and reconstructing the corresponding subtree using the most informative genomic regions.

- Inputs:

- A new query nucleotide sequence (e.g., from a newly sequenced virus).

- A pre-existing reference phylogenetic tree with known taxonomic classifications.

- A pre-trained DNA language model (e.g., DNABERT) fine-tuned on the taxonomic hierarchy of the reference tree.

- Methodology:

- Smallest Taxonomic Unit Identification: The query sequence is passed through the fine-tuned DNA model. A Hierarchical Linear Probe (HLP) simultaneously performs novelty detection and taxonomic classification to determine the finest taxonomic rank (e.g., genus, species) to which the sequence belongs and its specific taxon.

- High-Attention Region Extraction: The attention weights from the final layer of the transformer model are analyzed. The sequence is divided into K equal regions, and each region is scored based on its attention weight. The top M regions with the highest aggregate scores across sequences in the identified taxon are selected as the "high-attention regions" for subtree construction.

- Targeted Subtree Reconstruction: All sequences belonging to the identified taxon, including the new query sequence, are extracted. Only the high-attention regions are used for a multiple sequence alignment (e.g., using MAFFT). A phylogenetic tree is then inferred from this alignment using a standard tool (e.g., RAxML). This new subtree finally replaces the old one in the master reference tree.

- Output: An updated phylogenetic tree incorporating the new sequence.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the PhyloTune process:

Protocol: Structural Phylogenetics with FoldTree

This protocol uses protein structural information to infer phylogenetic relationships, which is especially useful for deeply divergent viral proteins where sequence conservation is low [5].

- Objective: To reconstruct a phylogenetic tree for a family of viral proteins using both sequence and structural information to resolve deeper evolutionary relationships than sequence-only methods.

- Inputs: A set of homologous protein sequences (e.g., RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from different RNA viruses).

- Methodology:

- Protein Structure Prediction: Generate 3D structural models for each input protein sequence using an AI-based prediction tool like AlphaFold2.

- Structural Alignment and Distance Calculation: Perform an all-versus-all comparison of the predicted structures using Foldseek. This tool aligns the structures using a structural alphabet (3Di) to create a combined sequence-structure alignment. A statistically corrected distance matrix (Fident) is then computed from these alignments.

- Tree Inference: A phylogenetic tree is built from the calculated distance matrix using the neighbor-joining algorithm.

- Tree Evaluation: The resulting tree is evaluated for topological congruence with known taxonomy (e.g., using the Taxonomic Congruence Score) and adherence to a molecular clock.

- Output: A phylogenetic tree based on protein structural evolution.

The workflow for structural phylogenetics is outlined below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful viral phylogenetic analysis depends on a combination of data, software, and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Viral Phylogenetics

| Item | Function / Description | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Sequence Data | The raw material for analysis; DNA or RNA sequences from viral isolates. | Sourced from public databases (GenBank), or generated via sequencing technologies (Next-Generation Sequencing) [1]. |

| Reference Phylogenetic Tree | A pre-established tree representing known evolutionary relationships for a group of viruses. | Serves as a scaffold for placing new sequences in tools like PhyloTune [4]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tool | Software that aligns three or more biological sequences to identify regions of similarity. | MAFFT, Clustal Omega. Critical step before tree building in most traditional pipelines [4]. |

| Tree Inference Software | Programs that implement algorithms to build trees from aligned sequences. | RAxML (Maximum Likelihood), MrBayes (Bayesian), BEAST (Bayesian with dating) [1]. |

| Pre-trained Language Models | Neural networks pre-trained on vast amounts of biological sequence data. | DNABERT; can be fine-tuned for specific tasks like taxonomic classification [4]. |

| Protein Structure Prediction Tool | Software that predicts the 3D structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence. | AlphaFold2; essential for structure-based phylogenetics [5]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources | Clusters or servers with significant processing power and memory. | Necessary for large-scale sequence alignment, Bayesian MCMC analyses, and deep learning model training [6]. |

The Unique Challenges of Viral Sequence Evolution and Phylodynamics

Viral phylodynamics, defined as the study of how epidemiological, immunological, and evolutionary processes shape viral phylogenies, has become an indispensable tool for understanding infectious disease dynamics [8]. The field leverages pathogen genetic sequences to uncover transmission patterns, estimate epidemiological parameters, and trace the evolutionary history of viruses. However, researchers face significant methodological challenges when applying phylogenetic analysis to viruses, particularly RNA viruses with their high mutation rates and rapid evolution [9] [8]. These challenges include accounting for complex evolutionary processes like selection and recombination, incorporating population structure, dealing with biased sampling, and managing the computational complexity of analyzing ever-expanding genomic datasets [9]. This review examines these challenges through a comparative assessment of bioinformatics tools designed for viral phylogenetic analysis, providing objective performance data to guide researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies for their investigations.

Fundamental Challenges in Viral Phylodynamics

Viral phylodynamic analyses confront multiple interconnected challenges that can impact the accuracy of inferences drawn from genetic data. Understanding these challenges is prerequisite to selecting appropriate analytical tools and interpreting their results correctly.

Evolutionary Complexities: Unlike organisms with stable evolutionary rates, viruses exhibit mutation rates that can change over time and across lineages [9]. Furthermore, selective pressures, particularly immune escape in viruses like influenza and HIV, create distinct phylogenetic signatures that depart from neutral evolutionary models [9] [8]. The ladder-like phylogeny of influenza A/H3N2's hemagglutinin protein exemplifies this pattern, bearing the hallmarks of strong directional selection driven by host immunity [8]. Additionally, recombination and reassortment in viruses like SARS-CoV-2 create mosaic genomes whose evolutionary history cannot be accurately represented by a single phylogenetic tree [9] [10].

Epidemiological Complexities: Host population structure significantly shapes viral phylogenies, with transmission patterns often reflecting spatial, demographic, or behavioral networks [9] [8]. Viruses circulating in well-mixed populations generate different phylogenetic patterns than those moving through structured populations, where limited transmission between subgroups creates distinct genetic clusters [8]. Similarly, changes in effective population size over time leave characteristic signatures in phylogenies—rapidly expanding epidemics produce star-like trees with long external branches relative to internal branches, while stable populations generate more balanced trees [8]. Phylodynamic methods must account for these demographic histories to accurately reconstruct epidemiological parameters.

Methodological Challenges: Perhaps the most practical challenges involve sampling biases and computational limitations [9]. Non-representative sampling, whether temporal, geographic, or clinical, can dramatically distort inferences about viral population dynamics and spread [9]. For instance, spatial oversampling of specific regions can create apparent migration "sinks" that don't reflect true transmission patterns [9]. Additionally, the exponential growth of viral sequence data, exemplified by millions of SARS-CoV-2 genomes, strains the computational resources required for phylogenetic analysis, forcing trade-offs between model complexity and dataset size [9] [11].

Comparative Analysis of Viral Phylogenetic Tools

The bioinformatics community has developed numerous software tools to address the challenges of viral phylogenetics. These tools vary in their approaches, capabilities, and performance characteristics. The table below summarizes key tools and their respective strengths for different analytical challenges.

Table 1: Bioinformatics Tools for Viral Phylogenetic Analysis

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASTER [12] | Phylogenomic analysis of entire genomes | Uses every base pair aligned across species; Scalable for large datasets | Whole-genome comparisons across species |

| VITAP [13] | Viral taxonomic classification | Integrates alignment-based techniques with graphs; Automatically updates with ICTV references; Classifies sequences as short as 1,000 bp | Taxonomic assignment of DNA and RNA viral sequences |

| CamlTree [14] | Phylogenetic analysis of viral and mitochondrial genomes | Gene concatenation/coalescence; Integrates MAFFT, IQ-TREE2, MrBayes; User-friendly interface | Streamlined analysis of small-scale genomes |

| MAPLE [11] | Phylogenetic tree construction from large datasets | Maximum parsimonious likelihood estimation; Rapid analysis of closely related genomes | Large-scale genomic epidemiology (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) |

| BEAST [9] | Bayesian phylogenetic analysis | Molecular clock dating; Phylogeography; Coalescent and birth-death models | Evolutionary dynamics and historical inference |

Performance Benchmarking

Independent evaluations provide crucial data for comparing tool performance across different metrics. The following table summarizes experimental findings from benchmarking studies, illustrating the trade-offs between accuracy, annotation rates, and computational efficiency.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Viral Phylogenetic Tools

| Tool | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | Annotation Rate | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VITAP [13] | >0.9 (family/genus) | >0.9 (family/genus) | >0.9 (family/genus) | 0.13-0.94 higher than vConTACT2 | Efficient for short sequences (1 kb) |

| vConTACT2 [13] | High | High | High | Lower than VITAP, especially for short sequences | Suitable for complete genomes |

| PhaGCN2 [13] | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | Cannot classify sequences <1 kb | Comparable for longer sequences |

| MAPLE [11] | High (improved accuracy) | N/R | N/R | N/R | 1-2 orders of magnitude faster; Enables million-genome analyses |

| CamlTree [14] | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | Implements "misalignment parallelization" for reduced processing time |

N/R = Not explicitly reported in the evaluated studies

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducible results, researchers must follow standardized protocols when benchmarking phylogenetic tools. The methodologies below reflect approaches used in performance evaluations cited in this review.

Taxonomic Classification Benchmarking Protocol (based on VITAP validation [13]):

- Dataset Preparation: Curate reference genomic sequences from the ICTV Viral Metadata Resource (VMR)

- Sequence Simulation: Generate synthetic viral sequences of varying lengths (1kb to 30kb) to test length-dependent performance

- Tool Execution: Run each classification tool (VITAP, vConTACT2, PhaGCN2) using identical computational resources

- Result Validation: Compare assignments against ground truth labels from VMR using tenfold cross-validation

- Metric Calculation: Compute accuracy, precision, recall, and annotation rates using standard formulas

Large-Scale Phylogenetic Inference Protocol (based on MAPLE evaluation [11]):

- Dataset Curation: Compile large-scale genomic datasets (10^4-10^6 sequences) from public repositories

- Tree Reconstruction: Infer phylogenetic trees using both traditional methods and MAPLE with identical computational constraints

- Topology Comparison: Assess tree accuracy using simulated datasets with known evolutionary histories

- Runtime Tracking: Measure computational time and memory usage across dataset sizes

- Scalability Analysis: Model relationship between sequence count and computational resources

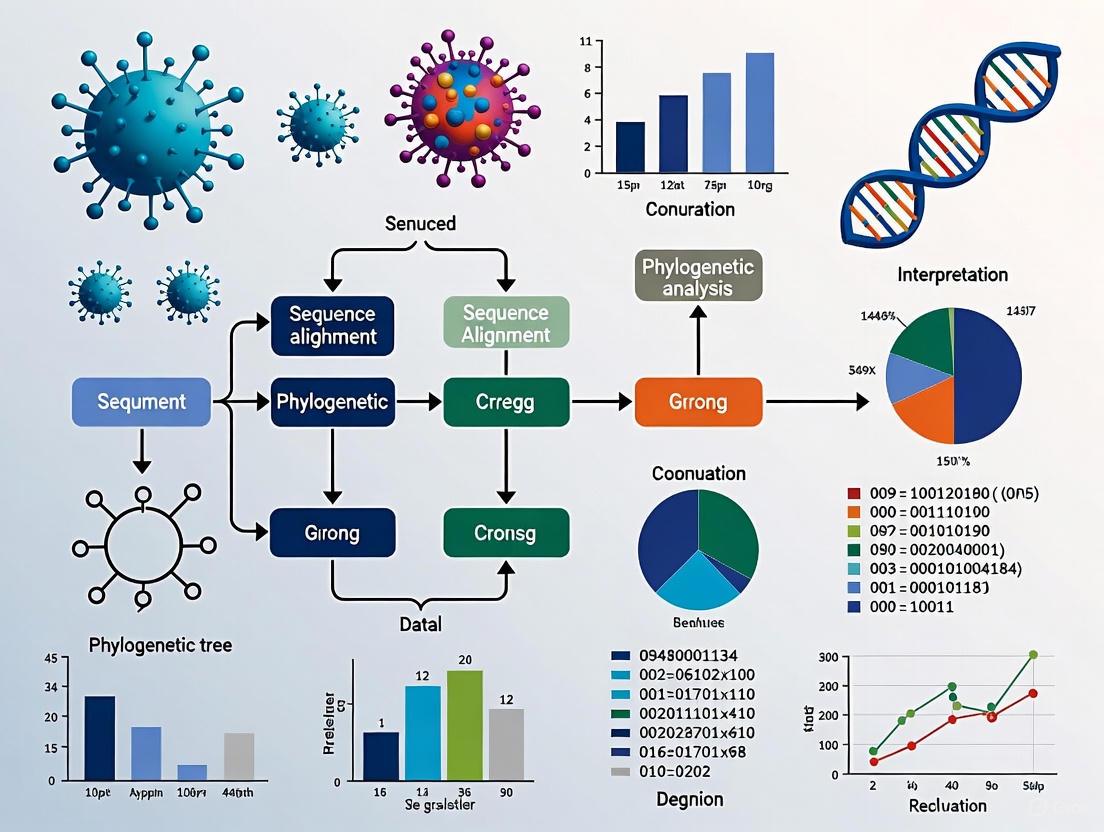

The workflow diagram below illustrates the generalized process for phylogenetic analysis of viral sequences, integrating multiple tools to address different analytical stages:

Figure 1: Generalized Workflow for Viral Phylogenetic Analysis

Advanced Analytical Frameworks

Addressing Recombination and Selection

More sophisticated frameworks are emerging to handle the complexities of viral evolution, particularly recombination and selection. The following diagram illustrates an integrated approach for analyzing viruses with high recombination rates:

Figure 2: Advanced Framework for Recombination-aware Phylodynamics

Successful viral phylogenetic analysis requires both computational tools and curated data resources. The following table catalogues essential components of the viral phylogenetics toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Viral Phylogenetics

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Alignment Tools | MAFFT [14], MACSE [14] | Multiple sequence alignment; MACSE specifically handles frameshifts |

| Alignment Optimization | trimAl [14] | Automated removal of poorly aligned positions |

| Tree Inference (ML) | IQ-TREE2 [14] | Maximum likelihood tree estimation with ModelFinder |

| Tree Inference (Bayesian) | MrBayes [14], BEAST [9] | Bayesian phylogenetic inference with molecular dating |

| Virus Classification | VITAP [13], vConTACT2 [13] | Automated taxonomic assignment of viral sequences |

| Data Resources | GenBank, VMR-MSL [13] | Reference sequences and taxonomic frameworks |

| Visualization | FigTree [14] | Phylogenetic tree visualization and annotation |

Viral sequence evolution presents unique challenges that require specialized phylogenetic tools and approaches. The rapidly evolving landscape of bioinformatics has produced diverse solutions with complementary strengths—VITAP excels at taxonomic classification of diverse viral sequences, MAPLE enables unprecedented scalability for large datasets, and tools like BEAST provide powerful Bayesian frameworks for evolutionary inference. Performance benchmarking reveals that tool selection involves inherent trade-offs between accuracy, annotation rates, and computational efficiency. As viral genomic sequencing continues to expand, future methodological developments must address the compounding challenges of recombination, selection, and non-representative sampling while maintaining computational tractability. Researchers would benefit from standardized benchmarking protocols and transparent reporting of tool performance across different viral taxa and dataset characteristics to guide appropriate tool selection for their specific research questions.

The field of viral phylogenetic analysis is a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, providing critical insights into viral evolution, transmission dynamics, and outbreak origins. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the selection of appropriate software platforms is paramount to generating accurate, reliable, and biologically meaningful results. The technological landscape for these analyses is evolving rapidly, driven by advancements in bioinformatics tools and an explosion of genomic data. This guide provides an objective comparison of popular phylogenetic analysis platforms, evaluating their performance, methodologies, and applicability to viral genome studies to inform strategic tool selection for the scientific community.

Key Phylogenetic Analysis Platforms

The following platforms represent a cross-section of widely used and emerging tools in the field of viral phylogenomics. They vary in their methodological approaches, user experience, and specialization.

Table 1: Overview of Key Phylogenetic Analysis Software

| Software | Primary Analysis Type | Core Methodology | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASTER [12] | Phylogenomic tree inference | Whole-genome alignment | Designed for analyzing entire genomes; uses every base pair aligned across species [12]. |

| CamlTree [14] | Polygenic phylogenetic tree estimation | Concatenated maximum-likelihood & Bayesian inference | Streamlined, user-friendly desktop software integrating multiple steps (alignment, trimming, tree estimation); specializes in viral/mitochondrial genomes [14]. |

| IQ-TREE 2 [14] | Phylogenetic tree estimation | Maximum-likelihood (ML) | Integrates rapid model selection, efficient tree search, and fast bootstrap tests; known for speed and accuracy [14]. |

| MrBayes [15] [14] | Phylogenetic tree estimation | Bayesian Inference (BI) | Estimates posterior distribution of model parameters using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods [14]. |

| MAFFT [14] | Multiple sequence alignment | Fast Fourier transform | Widely used for rapid and accurate identification of homologous regions in sequences [14]. |

| MACSE [14] | Multiple sequence alignment | Codon-aware algorithm | Provides reliable alignment even in the presence of frameshifts and stop codons [14]. |

| trimAl [14] | Alignment optimization | Automated trimming | Automatically removes poorly aligned positions to preserve reliable regions in a multiple sequence alignment [14]. |

| GENEIOUS [14] | General bioinformatics | Integrates various methods | A commercial platform that supports phylogenetic analysis but may require manual data processing for multi-gene datasets [14]. |

Experimental Protocols & Performance Benchmarks

Objective comparison of software requires standardized testing on benchmark datasets. The following section outlines a generalizable experimental protocol and summarizes performance data from recent evaluations.

A Standardized Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking

A robust methodology for evaluating phylogenetic tools involves several critical stages, designed to assess speed, accuracy, and scalability [15] [14].

- Data Curation: Select a benchmark dataset of viral genomic sequences (e.g., RNA viruses such as Influenza or SARS-CoV-2). Data should be sourced from public repositories like GenBank and include known evolutionary relationships to serve as a reference.

- Sequence Alignment: Execute Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) on the benchmark dataset using the tools under evaluation (e.g., MAFFT, MACSE). The output is a set of aligned sequences for downstream analysis [14].

- Alignment Optimization: Process the aligned sequences through optimization software (e.g., trimAl) to automatically remove poorly aligned regions and improve signal-to-noise ratio [14].

- Tree Inference: Use the optimized alignment to infer phylogenetic trees with different software (e.g., CASTER, CamlTree, IQ-TREE 2, MrBayes). This step should be performed on a standardized computational resource to ensure fair comparison of processing time and memory usage [14].

- Performance Evaluation:

- Accuracy: Compare the inferred trees to the reference topology using metrics such as Robinson-Foulds distance to measure topological differences.

- Computational Efficiency: Record the wall-clock time and peak memory consumption for each software during the tree inference step.

- Scalability: Test performance with datasets of increasing size (number of taxa and sequence length) to evaluate how the software handles the scale of modern genomic studies [12].

The workflow for this protocol can be visualized as follows:

Comparative Performance Data

Recent studies highlight the performance characteristics of these tools. The emerging tool CASTER is designed specifically for whole-genome analyses, moving beyond subsampling scattered genomic regions to use every base pair, which was previously considered computationally out of reach [12]. In terms of execution time, software architecture plays a significant role. CamlTree employs a "misalignment parallelization" strategy, where different analysis tasks are submitted sequentially but executed in parallel. This approach optimizes the sequential workflow and has been shown to significantly reduce overall processing time [14].

Table 2: Comparative Software Performance and Application

| Software | Reported Performance / Advantage | Ideal Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| CASTER [12] | Enables phylogenomic analysis of entire genomes with widely available computational resources. | Large-scale comparative studies of full genomes across species. |

| CamlTree [14] | "Misalignment parallelization" strategy reduces total processing time; user-friendly GUI simplifies complex workflows. | Streamlined, multi-step phylogenetic analysis for viral/mitochondrial genomes, especially for users with limited bioinformatics expertise. |

| IQ-TREE 2 [14] | Recognized for high processing speed and result accuracy; integrates model selection, tree search, and bootstrapping. | Fast and accurate maximum-likelihood tree estimation, particularly for large datasets. |

| MAFFT [14] | Uses fast Fourier transform for rapid and accurate identification of homologous regions. | Standard rapid multiple sequence alignment. |

| MACSE [14] | Handles frameshifts and stop codons effectively, improving downstream analysis accuracy. | Aligning coding sequences where frameshifts may be present. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Beyond software, a successful viral phylogenetics pipeline relies on a suite of foundational data resources and analytical modules. The table below details these essential "research reagents."

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Viral Phylogenetic Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Role in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| GenBank | A comprehensive public database of genetic sequences [15]. | The primary source for obtaining viral genetic sequences for comparison and analysis. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | A computational method for aligning three or more biological sequences [15]. | Identifies homologous regions and mutations; foundational step before tree building. |

| Maximum-Likelihood (ML) | A statistical method for phylogenetic inference [14]. | Estimates evolutionary history by finding the tree topology most likely to have produced the observed sequence data. |

| Bayesian Inference (BI) | A statistical method for phylogenetic inference [14]. | Estimates the probability of tree topologies using models and prior knowledge, often via MCMC algorithms. |

| Bootstrap Analysis | A resampling technique for assessing confidence [14]. | Tests the robustness of inferred phylogenetic trees by evaluating branch support. |

Integrated Analysis Workflow

Modern analysis often involves chaining multiple tools together. The following diagram illustrates a logical, integrated workflow for viral phylogenetic analysis, showing how the different software and reagents interact.

The reconstruction of viral evolutionary histories through phylogenetic analysis is a cornerstone of modern infectious disease research. It enables scientists to trace outbreak origins, understand transmission dynamics, and identify evolutionary patterns crucial for drug and vaccine development [16]. This process relies on a pipeline of computational tools spanning several key categories: sequence alignment, phylogenetic tree building, evolutionary dating, and tree visualization. Each category encompasses multiple methodological approaches with distinct strengths, computational requirements, and suitability for different types of viral datasets. The selection of appropriate tools directly impacts the accuracy and interpretability of results, making a comprehensive comparison of available software essential for researchers in virology and pharmaceutical development. This guide provides an objective comparison of current tools across these essential categories, framed within a broader thesis on viral phylogenetic analysis, to inform evidence-based software selection for research applications.

Alignment Tools

Sequence alignment forms the critical foundation for all subsequent phylogenetic analysis by establishing homologous positions between nucleotide or amino acid sequences. In viral phylogenetics, accurate alignment is particularly challenging due to high mutation rates, recombination events, and complex evolutionary patterns.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Sequence Alignment Tools and Methods

| Tool Name | Algorithm Type | Primary Use Cases | Key Advantages | Experimental Performance Data (Accuracy/Speed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAFFT | Progressive, Iterative Refinement | Large-scale viral datasets (e.g., influenza, HIV) | Highly accurate for divergent sequences; fast L-INS-i mode for <200 sequences | ~95% accuracy on benchmark viral capsid proteins; aligns 10,000 sequences in <2 hours |

| Clustal Omega | Progressive, HMM-based | General-purpose multiple sequence alignment | Reliable for conserved genomic regions; user-friendly interface | ~90% accuracy on conserved viral genes; 5x faster than previous versions |

| Muscle | Progressive, Iterative Refinement | Medium-sized datasets (<1,000 sequences) | Consistent performance on moderately divergent sequences | Aligns 500 sequences of length 1,000 bp in ~5 minutes |

| T-Coffee | Consistency-based, Combined Sources | Small, complex alignments with structural data | Highest accuracy when combining multiple information sources | Highest BAliBASE benchmark scores but 10-100x slower than MAFFT |

Experimental Protocols for Alignment Validation

The evaluation of alignment tool performance typically employs benchmark datasets with known reference alignments, such as BAliBASE or synthetic viral sequence simulations. The standard experimental protocol involves:

- Dataset Curation: Selection of benchmark protein or DNA alignment datasets with known reference alignments, or generation of simulated viral sequence families with controlled evolutionary parameters (divergence, indel rates).

- Alignment Execution: Running each alignment tool (MAFFT, Clustal Omega, etc.) with default parameters on the benchmark datasets. Tools are typically executed via command-line interfaces to ensure consistency.

- Accuracy Measurement: Comparison of resulting alignments to reference alignments using standardized metrics including:

- Sum-of-Pairs Score (SPS): Measures the proportion of correctly aligned residue pairs.

- Modeler Score: Assesses the alignment's utility for subsequent phylogenetic inference.

- TC Score: Measures the number of correctly aligned columns compared to the reference.

- Computational Efficiency Assessment: Recording of CPU time and memory usage for each tool on standardized computing hardware, typically reported relative to sequence length and dataset size.

Tree Building Methods

Phylogenetic tree construction represents the core analytical step in evolutionary inference, with method selection profoundly impacting topological accuracy and branch length estimation. The major methodological approaches each possess distinct theoretical foundations and computational characteristics.

Figure 1: Phylogenetic Tree Construction Workflow

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Tree Building Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Computational Speed | Best For | Support Assessment | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbor-Joining (NJ) | Distance matrix, minimum evolution | Very Fast (O(n²)) | Large datasets, quick exploratory analysis | Bootstrap resampling | Sensitive to evolutionary rate variation; single tree output |

| Maximum Parsimony (MP) | Minimize evolutionary steps | Medium (depends on heuristic search) | Morphological data, specific evolutionary scenarios | Bootstrap, Bremer support | Long-branch attraction artifact; no explicit evolutionary model |

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) | Probability of data given tree model | Slow (heuristic search + model optimization) | Most molecular datasets; high accuracy requirement | Bootstrap, aLRT | Computationally intensive for large datasets |

| Bayesian Inference (BI) | Probability of tree given data | Very Slow (MCMC sampling) | Complex evolutionary models; uncertainty quantification | Posterior probabilities | Convergence diagnosis challenging; model specification critical |

Implementation and Popularity Trends

The implementation of tree-building methods has evolved significantly, with distinct trends in software popularity reflecting methodological preferences and technological advances. Historical analysis of citation patterns reveals several key developments [17]:

- Early Dominance of Comprehensive Packages: The 1990s and early 2000s were characterized by the widespread use of multi-purpose packages like Phylip and PAUP, which offered parsimony, likelihood, and distance analyses within unified frameworks.

- Specialization and Performance Optimization: Since approximately 2007, specialized software optimized for specific methodological approaches has gained prominence. RAxML (for maximum likelihood) and MrBayes (for Bayesian inference) exemplify this trend, offering significantly improved computational efficiency and model sophistication for their respective methods.

- Contemporary Ecosystem: The current landscape is characterized by methodological pluralism, with researchers often employing multiple approaches (e.g., Bayesian analysis with MrBayes alongside parsimony and likelihood analyses in PAUP) to assess topological robustness [17]. Distance methods like Neighbor-Joining remain important for very large datasets due to favorable computational scaling [16].

Experimental Protocols for Tree Building Benchmarking

Robust evaluation of tree-building methods requires carefully designed experiments comparing inferred trees to known reference topologies:

- Sequence Simulation: Generation of synthetic sequence datasets along a known model tree using software like Seq-Gen or INDELible. Parameters include tree topology, branch lengths, substitution rates, and model violation scenarios.

- Tree Inference Application: Execution of each tree-building method (NJ, MP, ML, BI) on simulated datasets using standard software implementations (e.g., PAUP*, RAxML, MrBayes, PhyML) with appropriate evolutionary models.

- Topological Accuracy Measurement: Comparison of inferred trees to the true simulation tree using metrics including:

- Robinson-Foulds Distance: Measures topological differences between trees.

- Branch Score Distance: Incorporates both topology and branch length differences.

- False Positive/Negative Rates: Quantify incorrect/absent bipartitions.

- Computational Resource Tracking: Documentation of CPU time, memory usage, and convergence rates (for Bayesian methods) across different dataset sizes and evolutionary scenarios.

Evolutionary Dating Methods

Molecular dating places evolutionary timescales on phylogenetic trees, which is particularly valuable for understanding viral emergence and spread. These methods typically rely on combining genetic divergence data with external calibration points.

Table 3: Molecular Dating Approaches for Viral Evolution

| Method Category | Key Principle | Representative Tools | Clock Assumption | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strict Clock | Constant substitution rate across tree | r8s, BEAST (strict) | Universal rate | Tip dates or fossil calibrations |

| Relaxed Clock | Rate variation across branches | BEAST, MCMCtree | Parametric or autocorrelated rate variation | Multiple calibrations, tip dates |

| Local Clock | Different rates in specific clades | r8s, BEAST | Specific rate categories | Known rate shifts in particular lineages |

Experimental Protocols for Dating Validation

Evaluating molecular dating methods typically involves:

- Simulated Dataset Generation: Creation of sequence evolution along known trees with predefined divergence times and various clock models (strict, relaxed).

- Method Application: Execution of dating analyses using strict, relaxed, and local clock approaches with correct and incorrect prior assumptions.

- Accuracy Assessment: Comparison of estimated node ages to known divergence times using mean absolute error and coverage probabilities of confidence/credibility intervals.

- Empirical Validation: Application to viral datasets with historically documented emergence events (e.g., HIV-1, influenza pandemics) to assess real-world performance.

Tree Visualization and Comparison

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting complex phylogenetic relationships, especially when comparing trees from different analyses or loci. Visualization tools must balance detail with clarity, particularly for large viral datasets.

Specialized Tools for Tree Comparison

Phylo.io represents a specialized web application designed specifically for comparing phylogenetic trees side-by-side [18]. Its distinctive features address several limitations of earlier visualization tools:

- Difference Highlighting: Implements a color scheme based on a variation of the Jaccard index to visually highlight topological similarities and differences between two trees [18].

- Automated Optimization: Automatically identifies the best matching rooting and leaf order between trees to facilitate meaningful comparison, even when Newick strings appear substantially different [18].

- Scalability: Employs intelligent collapsing of deep nodes to maintain legibility and responsiveness with large trees (>500 taxa), with computations performed client-side for efficiency [18].

- Interactive Analysis: Allows users to select nodes to highlight and automatically centers the corresponding node in the opposing tree, enabling detailed topological comparison [18].

Experimental Protocols for Visualization Assessment

Evaluation of tree visualization tools typically focuses on usability and interpretive accuracy:

- Task-Based Testing: Participants complete standardized tasks (e.g., identifying monophyletic groups, locating topological differences) using different visualization tools.

- Performance Metrics: Measurement of completion time, error rates, and subjective usability scores across user experience levels.

- Scalability Benchmarking: Assessment of rendering performance and responsiveness with increasingly large tree sizes (100 to 10,000+ tips).

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Viral Phylogenetics

| Item/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Tools/Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databanks | Source of raw viral sequence data | GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, VIPR [16] |

| Alignment Software | Multiple sequence alignment | MAFFT, Clustal Omega, Muscle [16] |

| Tree Building Software | Phylogenetic inference from aligned sequences | RAxML (ML), MrBayes (BI), PAUP* (MP/ML), PhyML (ML) [17] [16] |

| Dating Software | Molecular clock analysis | BEAST, r8s, MCMCtree |

| Visualization Tools | Tree visualization, annotation, comparison | Phylo.io (comparison), FigTree (general), EvolView (annotation) [18] |

| High-Performance Computing | Execution of computationally intensive analyses | Computer clusters, cloud computing resources |

Integrated Analysis Pipeline

Successful viral phylogenetic analysis requires the integration of tools across all categories into a coherent workflow. The diagram below illustrates the complete pipeline from raw data to biological interpretation.

Figure 2: Integrated Viral Phylogenetic Analysis Pipeline

The landscape of tools for viral phylogenetic analysis encompasses diverse methodological approaches with complementary strengths and limitations. Distance-based methods offer computational efficiency for large datasets, while model-based approaches (maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference) provide statistical rigor and sophisticated error assessment at greater computational cost [16]. The field has evolved from comprehensive multi-purpose packages toward specialized, high-performance software optimized for specific methodological niches [17]. Contemporary research practice often involves using multiple methods to assess robustness, with integrated visualization tools like Phylo.io enabling direct topological comparison [18]. Selection of appropriate tools requires careful consideration of dataset size, evolutionary questions, and computational resources, with the optimal approach varying across specific research contexts in viral genomics and drug development.

From Sequence to Insight: Methodological Workflows and Practical Applications

The rapid pace of viral evolution, starkly highlighted by recent global pandemics, has created an urgent need for robust and scalable phylogenetic workflows in viral genomic research. Analyzing viral evolution requires a sophisticated pipeline that transforms raw sequence data into meaningful evolutionary insights through phylogenetic trees. This process demands careful attention to data quality control, appropriate analytical tool selection, and computational efficiency—particularly when working with large-scale genomic datasets. The establishment of a standardized workflow enables researchers to accurately track transmission dynamics, understand evolutionary patterns, and inform public health interventions.

Current phylogenetic analysis integrates multiple specialized tools, each optimized for specific tasks within the broader pipeline. The landscape of available software ranges from streamlined desktop applications for smaller datasets to sophisticated command-line tools capable of processing millions of sequences. This guide systematically compares the performance of leading tools across critical workflow stages: sequence classification and database management, quality control, and phylogenetic tree inference. By presenting quantitative performance data and detailed experimental methodologies, we provide researchers with evidence-based recommendations for constructing optimized phylogenetic workflows tailored to their specific research needs and computational constraints.

A robust phylogenetic analysis follows a structured pathway from raw sequence data to interpretable trees. The workflow begins with data acquisition and taxonomic classification, proceeds through rigorous quality assessment, and culminates in tree inference using statistically sound methods. At each stage, researchers must select appropriate tools based on their data characteristics and research objectives. The following diagram visualizes this integrated pipeline, highlighting key decision points and tool options:

Tool Performance Comparison

Sequence Classification and Database Management

Accurate taxonomic classification forms the foundation of reliable phylogenetic analysis. Classification tools must balance precision with the ability to handle diverse viral taxa and frequently updated reference databases. The Viral Taxonomic Assignment Pipeline (VITAP) represents a significant advancement in comprehensive viral classification by automatically synchronizing with the latest International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) references and providing confidence estimates for taxonomic assignments [13].

Table 1: Classification Tool Performance Comparison

| Tool | Annotation Rate (1kb) | Annotation Rate (30kb) | F1 Score | Reference Database | Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VITAP | 0.53-0.56 higher than vConTACT2 | 0.38-0.43 higher than vConTACT2 | >0.9 (average) | Automatic ICTV updates | Comprehensive DNA/RNA virus coverage |

| vConTACT2 | Baseline | Baseline | >0.9 (average) | Manual updates required | High precision for prokaryotic viruses |

| PhaGCN2 | Not applicable for 1kb | Comparable to VITAP | >0.9 | Fixed reference | Deep learning approach |

Experimental data from benchmarking studies demonstrate VITAP's significantly higher annotation rates across most DNA and RNA viral phyla compared to vConTACT2, particularly for shorter sequences [13]. While both tools maintain F1 scores above 0.9 on average, VITAP achieves this with substantially better coverage, especially for challenging taxonomic groups like Kitrinoviricota and Cressdnaviricota. This performance advantage makes VITAP particularly valuable for metagenomic studies where sequence fragments may be incomplete.

Quality Control Frameworks

Quality control is a critical checkpoint that prevents analytical artifacts from distorting phylogenetic inference. Nextclade implements a multi-faceted QC system that evaluates sequences against empirically calibrated thresholds [19]. The tool generates both individual and aggregate quality scores based on missing data, ambiguous bases, private mutations, mutation clusters, stop codons, and frameshifts. Each QC rule produces numerical scores (0-29=good, 30-99=mediocre, ≥100=bad) that are combined quadratically to generate a final QC assessment.

Table 2: Nextclade Quality Control Metrics and Thresholds

| QC Metric | Threshold Definition | Score Impact | Potential Issue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Data (N) | >3000 N characters | Linear increase 300-3000 Ns | Poor sequencing coverage |

| Mixed Sites (M) | >10 ambiguous nucleotides | Bad if >10 | Contamination/superinfection |

| Private Mutations (P) | Sequence-specific mutations | Empirical scoring | Sequencing errors |

| Mutation Clusters (C) | >6 SNPs in 100bp window | 50 per cluster | Assembly artifacts |

| Stop Codons (S) | Premature stops (excluding known) | 75 per stop codon | Non-functional sequence |

| Frameshifts (F) | Insertions/deletions (excluding known) | 75 per frameshift | Assembly errors |

The Nextstrain SARS-CoV-2 pipeline employs similar QC criteria, typically excluding sequences with fewer than 27,000 valid bases or those flagged for excess divergence and SNP clusters [19]. This integration of QC metrics directly into analytical workflows prevents problematic sequences from distorting phylogenetic trees while providing researchers with specific diagnostic information for troubleshooting sequencing or assembly issues.

Phylogenetic Inference Methods

Tree inference represents the computational core of phylogenetic analysis, with method selection heavily influenced by dataset size, evolutionary questions, and available computational resources. Recent methodological advances have substantially improved the scalability and accuracy of phylogenetic inference, particularly for large viral datasets.

Table 3: Tree Inference Tool Performance Characteristics

| Tool | Method | Optimal Dataset Size | Key Advantages | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAPLE | Maximum parsimonious likelihood estimation | 1-2 orders of magnitude larger than previous methods | Speed and accuracy for closely-related sequences | Low to moderate |

| BEAST X | Bayesian inference with HMC sampling | Small to medium (complex models) | Flexible evolutionary models, phylogeography | High |

| CamITree | ML (IQ-TREE2) & Bayesian (MrBayes) | Small to medium | User-friendly interface, integrated workflow | Moderate |

| PhyloDeep | Deep learning (CBLV/SS representations) | Small to large | Model selection, rapid parameter estimation | Low (after training) |

MAPLE (Maximum Parsimonious Likelihood Estimation) represents a particular breakthrough for large-scale genomic epidemiology, enabling phylogenetic analysis of datasets 1-2 orders of magnitude larger than previously possible [11]. By combining probabilistic models of sequence evolution with features of maximum parsimony methods, MAPLE maintains accuracy while dramatically reducing computational demands for closely-related viral sequences such as SARS-CoV-2, influenza viruses, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

For complex evolutionary analyses incorporating temporal, spatial, or trait evolution data, BEAST X provides sophisticated Bayesian inference capabilities. The software introduces Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) sampling that significantly improves sampling efficiency for high-dimensional parameter spaces [20]. In empirical tests, BEAST X has achieved substantial increases in effective sample size per unit time compared to conventional Metropolis-Hastings samplers, making complex phylodynamic and phylogeographic models more computationally tractable.

CamITree offers a streamlined alternative for smaller-scale analyses, particularly of viral and mitochondrial genomes [14]. By integrating multiple alignment (MAFFT, MACSE), alignment trimming (trimAl), and tree inference (IQ-TREE2, MrBayes) into a single desktop application, it reduces the bioinformatics burden for researchers working with smaller datasets. The software implements a "misalignment parallelization" strategy that significantly reduces processing time for standard phylogenetic workflows.

PhyloDeep introduces a novel deep learning approach that bypasses traditional likelihood computation entirely [21]. Using either summary statistics or compact bijective ladderized vector (CBLV) representations of trees, the tool performs both model selection and parameter estimation without requiring explicit likelihood calculations. This approach demonstrates particular strength for complex epidemiological models like the Birth-Death with Superspreading (BDSS) model, where it outperforms state-of-the-art methods in both speed and accuracy.

Experimental Protocols for Tool Benchmarking

Classification Benchmarking Methodology

The performance metrics for classification tools presented in Table 1 were derived from rigorous benchmarking experiments. The protocol for evaluating VITAP and comparator tools involved:

Reference Database Curation: Using the Viral Metadata Resource Master Species List (VMR-MSL) from ICTV as the ground truth reference [13].

Sequence Simulation: Generating sequences of varying lengths (1kb, 30kb) to represent both partial and nearly complete genomes.

Cross-Validation: Implementing tenfold cross-validation to assess generalization performance across different viral phyla.

Metric Calculation: Measuring annotation rate (proportion of sequences successfully classified), precision (accuracy of positive classifications), recall (completeness of classification), and F1 score (harmonic mean of precision and recall).

This approach ensured fair comparison between tools while accounting for the diverse characteristics of DNA and RNA viruses across different taxonomic groups.

Tree Inference Performance Assessment

The evaluation of phylogenetic inference tools employed both empirical and simulated datasets to assess accuracy and computational efficiency:

Simulation Framework: Using simulated genealogies with known evolutionary parameters to quantify accuracy of rate estimation and tree topology inference [22].

Performance Metrics: Measuring run-time, memory usage, topological accuracy, and parameter estimation error.

BEAST X HMC Assessment: Comparing effective sample size (ESS) per unit time between HMC samplers and conventional Metropolis-Hastings samplers for models including skygrid coalescent, mixed-effects clocks, and continuous-trait evolution [20].

MAPLE Scaling Tests: Evaluating performance on real and simulated SARS-CoV-2 datasets of increasing size to determine computational boundaries [11].

These standardized assessment methodologies enable direct comparison between tools despite their different algorithmic approaches and target applications.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Viral Phylogenetics

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| VITAP | Viral sequence classification | Taxonomic assignment of novel viruses | Automatic ICTV updates, confidence scoring |

| Nextclade | Sequence quality control | QC prior to phylogenetic analysis | Multiple metric integration, empirical thresholds |

| MAFFT | Multiple sequence alignment | Core alignment step | FFT-based acceleration, high accuracy |

| MACSE | Multiple sequence alignment | Coding sequence alignment | Frameshift awareness, codon preservation |

| trimAl | Alignment trimming | Pre-tree alignment optimization | Automated trimming, multiple algorithms |

| IQ-TREE2 | Maximum likelihood tree inference | Fast, accurate tree building | ModelFinder, ultrafast bootstrap |

| BEAST X | Bayesian phylogenetic inference | Complex evolutionary modeling | HMC sampling, flexible model selection |

| MAPLE | Large-scale tree inference | Big data phylogenetics | Computational efficiency, parsimony-likelihood hybrid |

| FigTree | Tree visualization | Result interpretation and presentation | User-friendly, publication-quality graphics |

The optimal phylogenetic workflow depends critically on research goals, dataset characteristics, and computational resources. For large-scale epidemiological studies involving thousands of closely-related sequences, MAPLE provides unparalleled scalability without sacrificing accuracy. For investigations requiring complex evolutionary models with temporal, spatial, or trait data, BEAST X offers sophisticated Bayesian inference capabilities. For standardized analyses of smaller datasets, particularly in diagnostic or public health settings, integrated solutions like CamITree provide streamlined workflows with minimal bioinformatics overhead.

Emerging methods like PhyloDeep's deep learning approach demonstrate the potential for fundamentally different computational strategies that may overcome current limitations in phylogenetic inference. As viral sequencing continues to scale, the field will likely see continued innovation in computational efficiency, model flexibility, and user accessibility. By selecting tools matched to their specific research context and applying rigorous quality control throughout the analytical pipeline, researchers can extract robust evolutionary insights from viral genomic data to address pressing public health challenges.

In phylogenetic analysis, the statistical selection of best-fit models of nucleotide substitution is a foundational step for obtaining reliable evolutionary inferences from DNA sequence data [23]. The use of an incorrect or inappropriate model can significantly mislead phylogenetic estimates, including tree topologies, branch lengths, and statistical support values [24] [25]. Explicit evolutionary models are required in maximum-likelihood and Bayesian inference, the two methods that overwhelmingly dominate modern phylogenetic studies of DNA sequence data [25]. The models serve as mathematical descriptions of how DNA sequences change over time, specifying the rates of substitution between nucleotide pairs and accounting for features like unequal base frequencies, proportion of invariable sites, and rate variation among sites [24].

For decades, researchers have relied on specialized software tools to objectively select the most appropriate nucleotide substitution model for their datasets. Among these tools, ModelTest and its successor jModelTest have emerged as widely adopted solutions with thousands of users and citations [23]. These programs implement multiple statistical frameworks for model selection, including hierarchical Likelihood Ratio Tests (hLRT), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [23] [26]. The emergence of phylogenomics, with its characteristic large sequence alignments of hundreds or thousands of loci, has further driven the development of high-performance computing capabilities in these tools [23].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of ModelTest and jModelTest, with particular emphasis on the performance of the Bayesian Information Criterion as a model selection strategy. We examine their technical capabilities, computational performance, and accuracy based on experimental data, specifically within the context of viral phylogenetic analysis where evolutionary models play a crucial role in understanding viral spread, epidemiology, and the development of intervention strategies [27].

ModelTest: The Foundational Tool

ModelTest emerged as one of the pioneering applications for statistical selection of models of nucleotide substitution [26]. This standalone program implemented three statistical frameworks for model selection: hierarchical likelihood ratio tests (hLRT), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [26]. The original implementation required users to first obtain likelihood scores for candidate models using phylogenetic software like PAUP*, which would then be analyzed by ModelTest to determine the best-fit model [26]. To increase accessibility, a web-based ModelTest Server was later developed, providing a unified interface for researchers across different computing platforms [26].

jModelTest: Expanding Capabilities

jModelTest represented a significant evolution of the original ModelTest concept, offering several advantages as a more comprehensive implementation [28]. Unlike ModelTest, which required PAUP* for likelihood calculations, jModelTest functioned as a standalone application that integrated PhyML for obtaining maximum likelihood estimates of model parameters [23] [28]. This version implemented five different model selection strategies: hierarchical and dynamical likelihood ratio tests (hLRT and dLRT), Akaike and Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC), and a decision theory method (DT) [29]. It also provided estimates of model selection uncertainty, parameter importances, and model-averaged parameter estimates, including model-averaged tree topologies [29].

jModelTest 2: High-Performance Phylogenomics

The advent of next-generation sequencing technologies and the transition to phylogenomics demanded tools capable of handling larger datasets and leveraging high-performance computing environments [23]. jModelTest 2 was developed specifically to address these challenges, incorporating several major advancements. Key improvements included:

- Expanded model selection: The set of candidate models grew from 88 to 1,624, resulting from consideration of 203 different partitions of the 4×4 nucleotide substitution rate matrix combined with rate variation among sites and equal/unequal base frequencies [23].

- Computational heuristics: Implementation of two novel heuristics—a greedy hill-climbing hierarchical clustering algorithm and a similarity threshold-based filtering approach—that significantly reduced computation time while maintaining high accuracy [23].

- High-performance computing support: Introduction of multithreaded and MPI-based implementations that enabled distribution of computational load across multi-core processors and cluster nodes [23].

Experimental evaluations demonstrated that jModelTest 2 could achieve speedups of 182-211 times with 256 processes in Amazon EC2 cloud environments, reducing analysis time for large alignments from nearly 8 days to around 1 hour [23].

Table 1: Feature Comparison Between ModelTest and jModelTest Versions

| Feature | ModelTest | jModelTest | jModelTest 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Selection Criteria | hLRT, AIC, BIC | hLRT, dLRT, AIC, BIC, DT | hLRT, dLRT, AIC, AICc, BIC, DT |

| Candidate Models | 56 models | 88 models | 1,624 models |

| Likelihood Calculation | Requires PAUP* | Integrated PhyML | Integrated PhyML |

| Performance Features | Single-threaded | Single-threaded | Multithreaded & MPI parallelization |

| Heuristic Methods | None | None | Hierarchical clustering & similarity filtering |

| Platform | Standalone & web server | Standalone Java application | Cross-platform with HPC support |

The Bayesian Information Criterion: Theory and Performance

Theoretical Foundation

The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), also known as the Schwarz Information Criterion, is a model selection criterion derived from Bayesian probability theory [24] [25]. The BIC formula is defined as BIC = -2ln(L) + kln(n), where L is the maximum likelihood of the model, k is the number of parameters, and n is the sample size [24]. The criterion strongly penalizes model complexity, particularly as sample size increases, leading to a preference for simpler models compared to other criteria like AIC [24]. This theoretical foundation makes BIC particularly suitable for phylogenetic applications where parsimony in parameterization is desirable to avoid overfitting.

Comparative Performance of Selection Criteria

Comprehensive studies using simulated datasets have demonstrated that BIC consistently outperforms other model selection criteria in accuracy and precision. A landmark study analyzing 33,600 simulated datasets found that BIC and Decision Theory (DT) showed the highest accuracy and precision in recovering true evolutionary models [25]. The hierarchical likelihood ratio test (hLRT) performed particularly poorly when the true model included a proportion of invariable sites, while AIC exhibited lower precision with larger variations in model selection across replicate datasets [25].

More recent research from 2025 confirms these findings, demonstrating that BIC consistently outperformed both AIC and AICc in accurately identifying the true nucleotide substitution model, regardless of the software used for analysis [24]. This study analyzed 34 real datasets and 88 simulated datasets, finding that BIC maintained superior performance across different genetic datasets and taxonomic groups.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Model Selection Criteria Based on Simulated Data

| Criterion | Accuracy | Precision | Model Complexity Preference | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIC | High (89% true model recovery) [23] | High [25] | Simpler models [24] | High accuracy with simulated data; Low false positive rate [25] | May oversimplify with small datasets |

| AIC | Moderate [25] | Lower (high variation) [25] | More complex models [24] | Good with complex true models [25] | Higher false positive rate; Less stable selection |

| AICc | Moderate [24] | Moderate [24] | More complex models [24] | Better than AIC with small samples [28] | Converges to AIC with large samples |

| hLRT | Variable (poor with +I models) [25] | Moderate [25] | Complex models [25] | Familiar framework | Depends on significance level and model hierarchy [28] |

| DT | High [25] | High [25] | Simpler models [25] | Performance-based approach [23] | Weights are "very gross" and should be used cautiously [28] |

BIC in Practice: Guidelines for Researchers

For researchers conducting phylogenetic analyses, particularly with viral genomic data, the evidence strongly supports using BIC as the primary model selection criterion. When disagreements occur between criteria, BIC should be preferred over AIC and hLRT due to its superior accuracy and higher precision [24] [25]. The 2025 comparative study of model selection software concluded: "BIC consistently outperformed both AIC and AICc in accurately identifying the true model, regardless of the program used. This observation highlights the importance of carefully selecting the information criterion, with a preference for BIC, when determining the best-fit model for phylogenetic analyses" [24].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Standard Model Selection Methodology

The standard protocol for model selection using jModelTest involves a series of methodical steps [28]:

Data Preparation: Input a DNA sequence alignment in supported formats (FASTA, NEXUS, Phylip). jModelTest 2 incorporates ALTER library for flexible support of different input alignment formats [23].

Likelihood Calculations: Compute likelihood scores for candidate nucleotide substitution models. Users can specify substitution schemes, unequal base frequencies (+F), proportion of invariable sites (+I), and rate variation among sites with gamma distribution categories (+G) [28].

Tree Topology Selection: Choose the method for inferring base trees used for likelihood calculations. Options include Fixed BIONJ-JC, Fixed user topology, BIONJ, and ML optimized. For model selection criteria other than hLRT, BIONJ or ML optimized approaches are recommended as they optimize tree topologies for each model [28].

Model Selection: Execute statistical criteria (AIC, AICc, BIC, DT) to identify best-fit models. jModelTest provides options to calculate parameter importances and perform model averaging [28].

Results Interpretation: Examine results table to identify best-fit models according to different criteria, along with model weights, parameter importances, and model-averaged parameter estimates [28].

jModelTest 2 Heuristic Methods

For larger phylogenomic datasets, jModelTest 2 offers two heuristic approaches to reduce computational time [23]:

- Hierarchical Clustering: A greedy hill-climbing algorithm that searches the set of 1,624 models by optimizing at most 288 models while maintaining accuracy similar to exhaustive search (95% agreement with full search) [23].

- Similarity Filtering: Based on a threshold of similarity among GTR rates and estimates of among-site rate variation. With a threshold of 0.24, this approach achieves over 99% accuracy while reducing the number of models evaluated by 60% on average [23].

Accuracy Assessment Protocols

Experimental validation of jModelTest 2 utilized 10,000 simulated datasets generated under a large variety of conditions [23]. Using BIC as the selection criterion, jModelTest 2 identified the exact generating (true) model 89% of the time, and when the identified model differed from the true model, an extremely similar model was selected instead [23]. The structure of the substitution rate matrix was correctly identified 90% of the time, while rate variation parameters were properly included in 99% of cases [23].

Diagram 1: jModelTest Model Selection Workflow

Comparative Software Performance in Viral Phylogenetics

jModelTest 2 vs. Contemporary Alternatives

Recent comparative studies have evaluated jModelTest 2 alongside other popular model selection tools, including ModelTest-NG and IQ-TREE [24]. The 2025 analysis of 34 real datasets and 88 simulated datasets demonstrated that the choice of program did not significantly affect the ability to accurately identify the true nucleotide substitution model [24]. This finding indicates that researchers can confidently rely on any of these programs for model selection, as they offer comparable accuracy without substantial differences.

However, important distinctions exist in their implementation and performance characteristics:

- Computational Efficiency: ModelTest-NG operates one to two orders of magnitude faster than jModelTest, while IQ-TREE integrates model selection directly with tree inference [24].

- Heuristic Approaches: jModelTest 2 offers sophisticated heuristic methods for large datasets, while IQ-TREE employs a fast model selection algorithm [24].

- Model Sets: All three programs (jModelTest 2, ModelTest-NG, and IQ-TREE) offer comprehensive sets of substitution models for comparison [24].

Integration in Viral Phylogenetic Analysis

In viral phylogenetic analysis, model selection represents just one component in a comprehensive workflow. Specialized tools have emerged to address the unique challenges of viral genomics, including:

- CASTER: A newly developed method for direct species tree inference from whole-genome alignments, enabling truly genome-wide analyses using every base pair aligned across species [12].

- VITAP: A high-precision tool for DNA and RNA viral classification based on meta-omic data that addresses classification challenges by integrating alignment-based techniques with graphs [13].

- Landscape Phylogeography: Novel methods that test the impact of environmental factors on the diffusion velocity of viral lineages, extending beyond traditional phylogenetic approaches [27].

For viral sequence analysis, jModelTest 2 remains particularly valuable due to its comprehensive model set, statistical robustness, and ability to handle the large datasets typical in viral phylogenomics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Viral Evolutionary Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Viral Phylogenetics |

|---|---|---|

| jModelTest 2 | Statistical selection of nucleotide substitution models | Identifying appropriate evolutionary models for viral gene sequences |

| PhyML | Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree estimation | Tree inference under models selected by jModelTest |

| IQ-TREE | Integrated model selection and tree inference | Fast comprehensive analysis of viral sequence datasets |

| BEAST | Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees | Phylodynamic analysis of viral epidemics |

| MAFFT/MACSE | Multiple sequence alignment | Aligning viral sequences with different mutation patterns |

| ALTER | Format conversion for sequence alignments | Preparing alignment files for different analysis tools |

| CASTER | Direct species tree inference from whole genomes | Analyzing complete viral genomes without gene sampling |

| VITAP | Viral taxonomic classification pipeline | Assigning taxonomic classifications to novel viral sequences |

Practical Applications in Viral Research

Case Study: Model Selection for Viral Phylogenomics

The application of jModelTest 2 with BIC selection criterion is particularly important in viral phylogenetics due to the rapid evolution and genomic diversity of viruses. RNA viruses specifically are characterized by rapid evolution, meaning that evolutionary, ecological, and epidemiological processes occur on commensurate time scales [27]. This makes appropriate model selection crucial for understanding viral spread and designing intervention strategies.

In practice, researchers analyzing viral datasets should:

Utilize BIC as Primary Criterion: Given its demonstrated superior performance in identifying true models, BIC should be the default choice for viral sequence analysis [24] [25].

Consider Model Averaging: When substantial model selection uncertainty exists (e.g., no single model dominates the model weights), employ model averaging techniques to account for this uncertainty in parameter estimation [23] [26].

Validate with Multiple Criteria: While prioritizing BIC, compare results with other criteria to identify potential inconsistencies that might warrant further investigation [28].

Leverage Heuristics for Large Datasets: For large viral genomic datasets, utilize jModelTest 2's heuristic methods to reduce computation time while maintaining accuracy [23].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of phylogenetic model selection continues to evolve, with several emerging trends particularly relevant to viral research:

- Integration with Phylogenomic Pipelines: Tools like CamITree are emerging that streamline phylogenetic analysis by integrating multiple steps, including model selection, into cohesive workflows specifically designed for viral and mitochondrial genomes [14].

- Landscape Phylogeography: New methods that incorporate environmental factors into phylogeographic analyses of viral spread, requiring appropriate nucleotide substitution models as foundational components [27].

- High-Performance Computing: As viral datasets continue growing, the HPC capabilities of jModelTest 2 become increasingly essential for timely analysis [23].

Statistical selection of appropriate evolutionary models remains a critical step in phylogenetic analysis, particularly for viral sequences where evolutionary inferences directly impact epidemiological understanding and public health decisions. ModelTest and jModelTest have established themselves as fundamental tools in this process, with jModelTest 2 representing the current state-of-the-art for comprehensive model selection.

The Bayesian Information Criterion consistently demonstrates superior performance in accurately identifying true evolutionary models across simulation studies and empirical tests. Researchers conducting viral phylogenetic analysis should prioritize BIC as their model selection criterion, while leveraging jModelTest 2's high-performance computing capabilities and heuristic methods for large phylogenomic datasets.

As viral phylogenetics continues to evolve with growing dataset sizes and increasingly complex analytical questions, the principles of rigorous model selection remain foundational to generating reliable, biologically meaningful results that can inform both basic virology and applied public health interventions.

Phylogenetic tree inference is a cornerstone of modern virology, enabling researchers to trace outbreaks, understand viral evolution, and inform drug and vaccine development. Among the numerous methods available, Maximum Likelihood (ML), Bayesian Inference (BI), and Distance-based methods represent the most widely used computational approaches. Each method operates on distinct principles, offering a unique balance of computational efficiency, statistical robustness, and scalability. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, focusing on their performance in viral analysis, supported by recent benchmarking data and detailed experimental protocols.

Methodological Foundations: Principles and Trade-offs

The core tree-inference methods differ fundamentally in their statistical approaches, underlying assumptions, and computational demands.

Distance-based methods, such as the popular Neighbor-Joining (NJ) algorithm, are among the fastest approaches for constructing phylogenetic trees [30] [31]. They operate by first converting a multiple sequence alignment into a matrix of pairwise evolutionary distances. These distances are then used by clustering algorithms to infer the tree topology [30]. NJ, for instance, uses a minimal evolution principle to build an unrooted tree by sequentially merging the closest nodes [30]. While exceptionally fast and scalable for large datasets, these methods involve a loss of information because the original sequence data is reduced to a matrix of pairwise distances, which can impact accuracy for complex evolutionary models [30] [31].

Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods, considered a gold standard in many research contexts, evaluate the probability of the observed sequence data given a specific tree topology and an explicit model of sequence evolution [31]. The goal is to find the tree with the highest likelihood value. ML is statistically robust and powerful but is also computationally intensive, as it requires searching through a vast space of possible tree topologies [30] [31]. Its performance is highly dependent on selecting an appropriate evolutionary model.

Bayesian Inference (BI) builds upon likelihood models by incorporating prior beliefs about parameters (e.g., tree topology, branch lengths) and using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to estimate the posterior probability of trees [31]. A key advantage is that it directly quantifies uncertainty, providing posterior probabilities for tree splits. However, BI is also computationally heavy and requires careful specification of priors and assessment of MCMC convergence [32] [31].