Optimizing Viral Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Guide to Pre-Analytical Issues and Specimen Choice for Researchers

This article provides a systematic analysis of the pre-analytical phase in viral diagnostics, a critical yet often overlooked determinant of test accuracy.

Optimizing Viral Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Guide to Pre-Analytical Issues and Specimen Choice for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis of the pre-analytical phase in viral diagnostics, a critical yet often overlooked determinant of test accuracy. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of specimen selection, details methodological applications for various viral syndromes, and offers evidence-based strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. Furthermore, it synthesizes validation frameworks and comparative data on specimen types, aiming to standardize practices, enhance diagnostic sensitivity, and inform the development of next-generation viral detection assays.

The Pre-Analytical Foundation: How Specimen Choice Dictates Diagnostic Success

In laboratory medicine, the total testing process is divided into three distinct stages: the pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases [1]. The pre-analytical phase, the initial and most vulnerable stage, encompasses all procedures from the point of test selection and patient identification to specimen collection, handling, and transport before the analysis begins [2] [3]. For viral diagnostics, this phase is particularly crucial as the viability of viral pathogens is highly dependent on specific handling conditions [4] [5]. Evidence indicates that 46% to 68% of all laboratory errors originate in the pre-analytical phase [2] [3], which can adversely affect the quality of subsequent data, increase diagnostic costs, and lead to suboptimal or incorrect patient treatment decisions [2]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and standardized protocols to help researchers and scientists navigate these critical pre-analytical challenges, with a specific focus on viral specimen management.

Understanding the Pre-Analytical Workflow

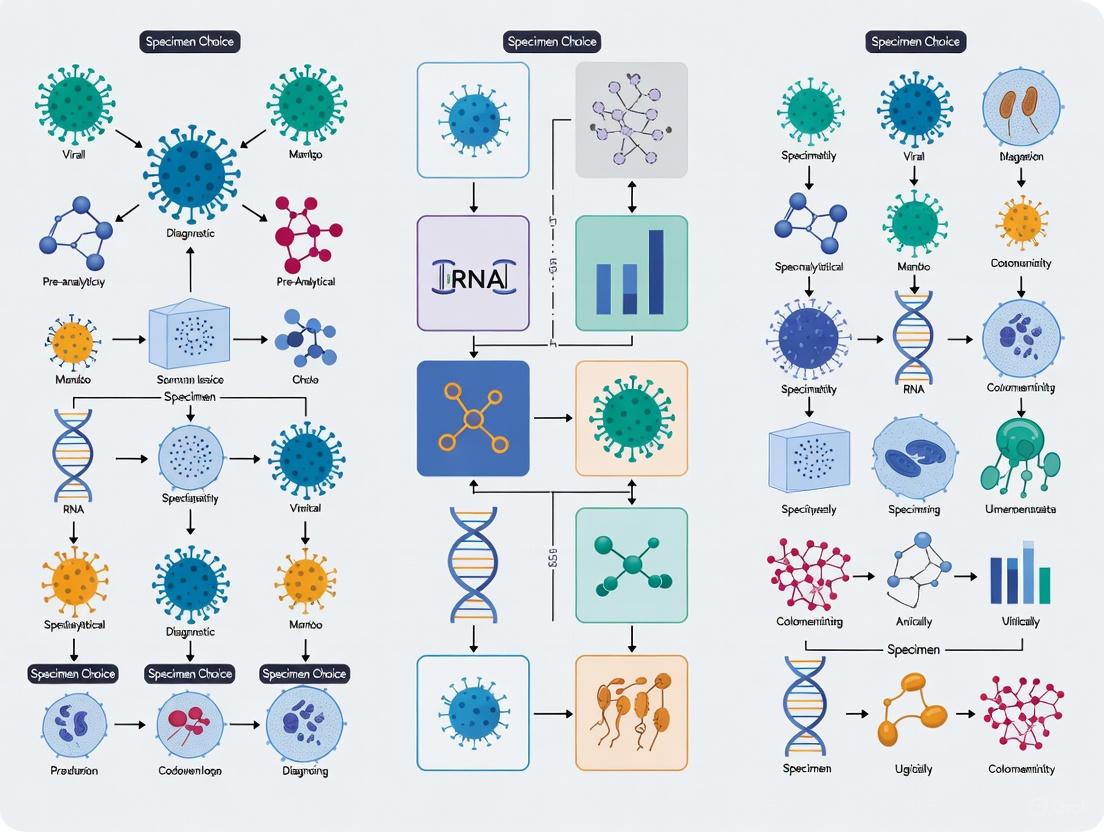

The pre-analytical phase is a multi-step process that begins even before a specimen is collected and ends when the sample is ready for analysis in the laboratory. Many of these steps occur outside the direct control of the laboratory staff, making standardization and clear communication paramount. The workflow can be visualized as a sequence of critical decision and action points.

Diagram 1: The Pre-Analytical Phase Workflow from Patient to Laboratory

This workflow highlights the sequence of critical steps where errors can occur. A failure at any point can compromise the entire diagnostic process, leading to inaccurate results, delayed diagnosis, and the need for specimen recollection.

Understanding the frequency and distribution of pre-analytical errors is essential for implementing effective quality control measures. The following table summarizes quantitative data on pre-analytical error rates and their common causes, providing a basis for prioritizing troubleshooting efforts.

Table 1: Frequency and Distribution of Common Pre-Analytical Errors

| Type of Pre-Analytical Error | Frequency (%) | Primary Impact on Viral Diagnostics |

|---|---|---|

| Unlabeled Sample | 35.8% [3] | Makes specimen untestable; impossible to link result to patient. |

| Clotted Anticoagulated Sample | 14.9% [3] | Clots can trap viruses/cells, making accurate analysis impossible. |

| Diluted Sample (e.g., from IV line) | 11.8% [3] | Dilutes viral concentration below detection limits. |

| Incorrect Patient Identification/Wrong MRC | 10.2% [3] | Leads to erroneous clinical decisions; major patient safety risk. |

| Hemolyzed Sample | 9.7% [3] | Interferes with PCR and other enzymatic assays. |

| Incorrect Collection Tube | 8.8% [3] | Inappropriate preservatives/anticoagulants can inactivate viruses. |

| Insufficient Sample Quantity | 8.8% [3] | Inadequate volume for required test(s). |

The data reveals that labeling and identification errors constitute the single largest category of pre-analytical mistakes. For viral diagnostics, errors related to sample condition—such as clotting, dilution, or use of incorrect tubes—are particularly detrimental as they can directly affect the integrity of the labile viral pathogen or its nucleic acids [4].

Viral Specimen Collection Protocols by Sample Type

The accuracy of viral diagnosis is heavily dependent on collecting the correct specimen type during the acute phase of infection when the viral load is highest [4] [6]. The table below outlines detailed methodologies for collecting various specimen types relevant to viral disease research.

Table 2: Standardized Protocols for Viral Specimen Collection

| Specimen Type | Optimal Collection Protocol | Special Handling & Transport |

|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal (NP) / Oropharyngeal (OP) Swab | NP: Insert flocked swab into posterior nasopharynx, hold for 5s [5].OP: Swab posterior pharynx/tonsils [5].Use: Dacron/rayon flocked swabs; avoid cotton/wood [5]. | Place in Viral Transport Media (VTM). Break applicator stick. Transport on ice [5]. |

| Vesicular Skin Lesion | Aspirate vesicle fluid with a fine-gauge needle/syringe [5]. Unroof lesion, vigorously swab base with flocked swab to collect cells [5]. | Place swab and fluid in VTM. Transport on ice [5]. |

| Stool / Rectal Swab | Collect 2-4 grams of stool or 1-2 mL in a leak-proof container [5] [6]. Rectal swab: insert 4-6 cm, roll against mucosa [6]. | Place swab in saline or VTM. Store at 4°C or frozen. Do not freeze with transport media if culturing [5]. |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Collect 1-3 mL via lumbar puncture in a sterile container [5]. | Do NOT add to VTM or preservative. Freeze immediately at -70°C or below [5]. |

| Blood / Serum | Collect 7-10 mL into serum separator tube (e.g., gold-top) [5]. Allow to clot at room temp, then centrifuge [5]. | Aliquot >2.5 mL of serum into a sterile tube. Ship immediately on ice or frozen [5]. |

| Tissue (Biopsy/Autopsy) | Collect as soon as possible post-disease onset or death. Place in sterile container [5]. | Add a small amount of sterile saline to keep moist. Fresh-freeze at -70°C. Avoid formalin for virus isolation [5] [6]. |

Key Technical Considerations:

- Viral Transport Media (VTM): VTM is essential for swab specimens. It typically contains a protein source (e.g., albumin), a buffer to maintain neutral pH, and antibiotics to suppress bacterial and fungal growth, which helps preserve viral viability during transport [4].

- Timing is Critical: For most acute viral illnesses, specimens obtained within the first 1-4 days of symptom onset are most likely to yield recoverable virus [4].

- Temperature Stability: Viruses vary in heat lability. Unless a delay of more than 4 days is anticipated, specimens should be held at 4°C and not frozen. If freezing is required, -70°C is essential, as conventional freezer temperatures (-10°C to -20°C) are detrimental to the infectivity of many viruses [4].

Troubleshooting Common Pre-Analytical Problems

This section provides a structured approach to identifying and resolving frequent pre-analytical issues, following a systematic troubleshooting methodology [7].

Scenario 1: Negative or Inhibited PCR Results

1. Identify the Problem: The PCR reaction failed—no amplification product is detected on the gel, but controls are fine.

2. List Possible Explanations:

- DNA/RNA Template: Degradation or insufficient concentration.

- Inhibitors: Presence of PCR inhibitors in the sample (e.g., from collection materials).

- Collection Error: Use of inappropriate swab type (e.g., cotton or wooden shaft).

- Storage/Transport: Improper temperature compromised the nucleic acid integrity.

3. Collect Data & Eliminate Explanations:

- Check the sample integrity (e.g., Bioanalyzer trace) and concentration.

- Review collection records: Was a recommended swab (e.g., flocked plastic) used?

- Check transport temperature logs.

4. Identify the Cause & Solution:

- Cause: Inhibitors from cotton swabs or sample degradation due to slow transport.

- Solution: Standardize collection kits to use only dacron/rayon flocked swabs and implement strict, monitored cold-chain transport [5].

Scenario 2: Failed Viral Culture

1. Identify the Problem: No cytopathic effect (CPE) is observed in cell culture, despite high clinical suspicion.

2. List Possible Explanations:

- Non-viable Virus: The virus was inactivated before culture.

- Delayed Transport: Sample not processed in a timely manner.

- Incorrect Media: Use of bacterial swab media without viral stabilizers.

- Old Lesion: Sampled from a crusted versus a fresh, fluid-filled vesicle.

3. Collect Data & Eliminate Explanations:

- Confirm the sample was placed in VTM, not bacterial transport media.

- Check the time from collection to lab receipt.

- Verify the nature of the lesion sampled.

4. Identify the Cause & Solution:

- Cause: Sample was delayed in transit for >72 hours without proper cooling or was collected from an old lesion.

- Solution: Ensure samples are shipped overnight on ice packs and that collection from skin lesions prioritizes fresh vesicles [4] [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important step to reduce pre-analytical errors in a research setting? A: Implementing a system of positive patient identification and specimen labeling at the bedside is paramount. Unlabeled specimens are the most common pre-analytical error, rendering a specimen useless and requiring a costly and invasive recollect [3]. Barcode ID systems can drastically reduce these errors [1].

Q2: Why is the type of swab so critical for viral diagnostics? A: Cotton and calcium alginate swabs or swabs with wooden sticks may contain substances that inactivate some viruses and inhibit molecular tests like PCR. Dacron or rayon flocked swabs are recommended because they do not interfere with assays and release their collected sample more efficiently into transport media [5].

Q3: How long can viral specimens be stored before processing, and at what temperature? A: For optimal recovery, process specimens as soon as possible. If a delay is unavoidable, most specimens for molecular testing can be refrigerated at 4°C for 1-2 days. For longer storage, freeze at -70°C or lower. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Note that for viral culture, delays significantly reduce viability, and freezing can be detrimental unless at ultra-low temperatures [4] [5].

Q4: Our lab frequently receives clotted EDTA samples for molecular testing. What is the likely cause? A: Clots in anticoagulated tubes are typically due to improper mixing after collection or an underfilled tube, leading to an incorrect blood-to-anticoagulant ratio. The solution is to train phlebotomists to invert the tube gently 8-10 times immediately after collection to ensure proper mixing [3].

Q5: What are the key elements of a good specimen rejection policy? A: A clear policy should define unambiguous rejection criteria (e.g., unlabeled, gross hemolysis, wrong container, clotted anticoagulated sample). The process must include immediate notification of the clinical/research team, documentation of the reason for rejection, and a mechanism for root cause analysis to prevent future occurrences [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key materials and their functions critical for ensuring the integrity of viral specimens during the pre-analytical phase.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Viral Specimen Management

| Item | Function & Rationale | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Transport Media (VTM) | Preserves viral viability and prevents desiccation during transport. Contains antibiotics to prevent bacterial overgrowth. | Essential for swab specimens intended for culture or rapid antigen tests. |

| Universal Transport Media (UTM) | A refined VTM formulation validated for both viral culture and molecular applications (PCR/NAT). | Preferred for multi-purpose testing to avoid the need for splitting samples. |

| Dacron/Rayon Flocked Swabs | Plastic-shafted swabs designed to release a high percentage of captured cells and virus into transport media. | Avoid calcium alginate or cotton swabs with wooden sticks, which contain inhibitors [5]. |

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes (Purple Top) | Prevents coagulation by chelating calcium. Used for whole blood assays and plasma preparation for viral load testing (e.g., PCR). | Must be inverted 8-10 times after collection to prevent clotting [3]. |

| Serum Separation Tubes (SST, Gold Top) | Contains a gel barrier that separates serum from clotted blood cells during centrifugation. | Used for serology (antibody detection). Must clot completely before centrifugation [5]. |

| Stool Collection & Transport Kits | Contains preservatives that stabilize nucleic acids and inactivate opportunistic pathogens for safe transport. | Crucial for stabilizing labile viruses like rotavirus and norovirus in stool. |

| RNA/DNA Stabilization Tubes | Contains reagents that immediately lyse cells and stabilize nucleic acids, preventing degradation. | Ideal for preserving viral RNA/DNA for sensitive downstream molecular assays. |

Visualization of Pre-Analytical Error Impact

The distribution of errors across the testing process is not uniform. The following diagram illustrates the relative proportion of errors that occur in each phase of the total testing process, highlighting why the pre-analytical phase demands the most rigorous attention.

Diagram 2: Relative Proportion of Laboratory Errors by Phase

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Pre-Analytical Errors in Viral Specimen Collection

This guide addresses frequent issues encountered during the collection of specimens for viral load and shedding kinetics studies.

Problem 1: Inconsistent Viral Load Results from Upper Respiratory Tract Samples

- Question: Why am I getting highly variable viral load readings from nasopharyngeal swabs collected from the same patient cohort over time?

- Answer: Variability can stem from several pre-analytical factors. The shedding kinetics of the virus itself are a primary factor; viral load in the upper respiratory tract typically peaks around symptom onset and declines over the following 1-3 weeks [8] [9]. Furthermore, the anatomical site within the upper respiratory tract matters. Some studies report higher viral RNA in nasal swabs, while others note higher loads in throat specimens, indicating that consistent swab technique and location are critical [9]. Finally, the quality of the sample is paramount. Prolonged exposure to ambient temperature or repeated freeze-thaw cycles can drastically degrade the virus and viral RNA, leading to lower or inconsistent measurements [8].

Problem 2: Failure to Isolate Infectious Virus in Cell Culture Despite Low RT-PCR Ct Values

- Question: My patient samples show low Ct values, suggesting high viral RNA, but I consistently fail to isolate infectious virus in cell culture. What could be wrong?

- Answer: A positive RT-PCR result indicates the presence of viral RNA but does not distinguish between replication-competent (infectious) virus and non-infectious viral fragments [8] [9]. The correlation between RNA viral load and the presence of infectious virus is not absolute. Furthermore, the probability of isolating infectious virus decreases significantly with time after symptom onset, often beyond 8-10 days, even if RNA remains detectable [8]. Pre-analytical handling is a major culprit. To preserve infectious virus, swab samples must be immediately submerged in an appropriate viral transport medium and stored at -80°C as soon as possible after collection. Deviations from this protocol can cause complete loss of infectious viral particles [8].

Problem 3: Discrepancy in Detection Between Different Specimen Types

- Question: Why does a patient's saliva test negative for viral RNA while their nasopharyngeal swab is positive, or vice versa?

- Answer: The anatomical site of collection is a key determinant because infection dynamics can differ qualitatively across tissues [10]. The oral cavity and the nasopharynx represent distinct compartments. For SARS-CoV-2, some individuals may show distinct viral shedding patterns in saliva, which do not always mirror those in the respiratory tract [10]. Saliva itself presents handling challenges, as it contains RNases and a large microbiota that can degrade viral RNA or increase background noise, potentially affecting detection sensitivity [10].

Problem 4: Specimen Contamination During Gross Handling

- Question: How can I prevent cross-contamination between specimens during processing in the gross room?

- Answer: Contamination is a significant pre-analytical variable that can lead to false positives. It is essential to establish and follow strict standard operating procedures for the gross room and histology laboratory. This includes thorough cleaning of surfaces and equipment between specimens and, when applicable, working within a biosafety cabinet to contain aerosols, especially when handling infectious samples or opening sample tubes [11]. Pre-analytical variables are estimated to account for up to 75% of laboratory errors, highlighting the need for meticulous manual procedures [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Viral Shedding and Specimen Selection

FAQ 1: How do viral shedding kinetics influence the timing of specimen collection?

The timing of collection is critical and should align with the peak shedding period for the specific virus and anatomical site. For SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract, the highest viral loads and thus the highest probability of detecting infectious virus occur just before and immediately after symptom onset [8] [9]. Collection too early in the incubation period or too late during convalescence can result in false negatives or detection of non-infectious viral RNA. Shedding duration varies by individual and disease severity, with severe cases often shedding virus for longer periods [9].

FAQ 2: What is the relationship between viral load and disease severity or transmission risk?

Higher viral loads in the respiratory tract are generally associated with a greater risk of onward transmission [8]. Regarding severity, several studies indicate that patients who develop severe COVID-19 tend to have higher baseline viral loads in their respiratory specimens compared to those with mild disease [9]. However, it is crucial to remember that viral load is only one factor, and host immunity plays a significant role in determining ultimate disease severity.

FAQ 3: How does the choice of anatomical site impact the detection of infectious virus versus viral RNA?

The anatomical site affects both the amount and duration of viral shedding. For SARS-CoV-2, lower respiratory tract (LRT) samples like sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid often show higher viral loads and longer shedding durations compared to upper respiratory tract samples like nasopharyngeal swabs [9]. While LRT samples may be more sensitive, they are more challenging to collect routinely. Furthermore, viral RNA can be detected in non-respiratory specimens like stool for extended periods, but these sites rarely yield infectious virus and are not considered relevant for transmission [8] [9].

FAQ 4: What are the key differences between using PCR and antigen tests as proxies for infectiousness?

RT-PCR is highly sensitive for detecting viral RNA but cannot differentiate infectious from non-infectious virus. Antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests (Ag-RDTs), while less sensitive, better correlate with the presence of infectious virus because they detect viral proteins, which are typically present in high amounts when the virus is actively replicating [8]. Therefore, a positive Ag-RDT is often a more direct indicator of potential infectiousness than a positive PCR, which can remain positive long after the active infection has cleared.

Table 1: Viral Shedding Dynamics by Anatomical Site and Disease Severity (SARS-CoV-2 Example)

| Anatomical Site | Peak Viral Load (Post-Symptom Onset) | Typical Shedding Duration (RNA) | Presence of Infectious Virus | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Respiratory Tract | Around symptom onset [9] | 1-3 weeks [9] | Highest around peak viral load; rarely isolated beyond 10 days in mild cases [8] [9] | Non-invasive collection; site (nasal vs. throat) can influence viral load [9]. |

| Lower Respiratory Tract | ~2 weeks [9] | Longer than URT; can exceed 3 weeks [9] | Can be isolated for longer periods (e.g., up to 18 days) [9] | Higher viral loads than URT; collection is more complex (sputum/BALF) [9]. |

| Saliva | Varies by individual shedding pattern [10] | Highly heterogeneous (stratified into groups averaging 11.5, 17.4, and 30.0 days) [10] | Positivity correlates with infectiousness [10] | Easy self-collection; dynamics may not mirror URT; susceptible to RNases [10]. |

| Stool | 3-4 weeks [9] | Can be several weeks [9] | Very rarely isolated [8] [9] | Not relevant for transmission; useful for wastewater surveillance. |

Table 2: Comparison of Key Diagnostic Methods for Viral Detection

| Method | Target | Distinguishes Infectious Virus? | Turnaround Time | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus Isolation (Cell Culture) | Replication-competent virus | Yes (Gold Standard) | Days to weeks | Confirms presence of infectious virus | Requires BSL-3 lab; slow; influenced by pre-analytics [8]. |

| RT-PCR | Viral RNA | No | Hours to 1 day | High sensitivity; gold standard for initial diagnosis | Detects RNA fragments, not necessarily live virus [8] [9]. |

| Antigen-Detecting Rapid Test (Ag-RDT) | Viral proteins | Better correlate than PCR | Minutes | Fast; low cost; good proxy for infectiousness | Lower sensitivity than PCR [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Virus Isolation and Titration from Respiratory Specimens

Objective: To qualitatively and quantitatively determine the presence of infectious SARS-CoV-2 in clinical specimens.

Methodology:

- Specimen Collection & Transport: Collect nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs and immediately place them in viral transport medium. Store at 4°C for short-term (<48 hours) or -80°C for long-term storage. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [8].

- Cell Culture Inoculation: Under Biosafety Level 3 (BSL-3) conditions, inoculate the specimen onto permissive cell lines, such as Vero E6 (African green monkey kidney cells) or Calu-3 (human lung adenocarcinoma). These cells express ACE2 and TMPRSS2, receptors important for viral entry [8].

- Incubation and Observation: Incubate inoculated cells at 37°C with 5% CO2. Monitor daily for cytopathic effects (CPE) using light microscopy. SARS-CoV-2-specific CPE includes syncytium formation, cell rounding, detachment, and degeneration [8].

- Confirmation & Quantification:

- Qualitative Confirmation: Confirm infection by detecting viral RNA via RT-PCR in the cell culture supernatant, demonstrating an increase in viral load over time, or by immunostaining for viral proteins [8].

- Quantification: Use plaque assays, focus-forming assays, or the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) method to quantify the infectious virus titer in the original specimen [8].

Protocol 2: Profiling Viral Shedding Kinetics Using Longitudinal Saliva Sampling

Objective: To model and stratify individual-level viral shedding patterns in saliva.

Methodology:

- Cohort Design & Sampling: Enroll symptomatic, infected participants. Collect longitudinal saliva samples at frequent intervals (e.g., daily or every other day) from symptom onset until at least two consecutive negative results are obtained [10].

- Viral Load Measurement: Extract viral RNA from saliva samples. Perform quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to determine the viral load in each sample. Express results as RNA copies per mL [10].

- Data Analysis & Mathematical Modeling: Fit a mathematical model (e.g., a target cell limited model with eclipse phase) to the longitudinal viral load data from each participant. Use the model to estimate key kinetic parameters, such as the peak viral load, time to peak, and viral clearance rate [10].

- Stratification Analysis: Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means) to the estimated kinetic parameters to identify distinct groups of patients with similar shedding patterns [10].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Diagram 1: Specimen Journey from Collection to Diagnosis

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Viral Load, Shedding & Infectiousness

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Shedding Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Flocked Swabs | Improved sample absorption and release for higher viral recovery from anatomical sites. | Copan FLOQSwabs [12]. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserves viral integrity and nucleic acids during specimen transport and storage. | BD Universal Viral Transport (UVT) System; Thermo Fisher Scientific InhibiSURE Viral Inactivation Medium [13] [12]. |

| Permissive Cell Lines | Essential for virus isolation and propagation to demonstrate infectivity. | Vero E6, Caco-2, Calu-3, Huh7 cells [8]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality viral RNA/DNA from various specimen types for PCR and sequencing. | Kits compatible with automated systems for high throughput. |

| qRT-PCR Assays & International Standards | Sensitive and quantitative detection of viral RNA. Standards allow for harmonization of results across labs. | Assays targeting specific viral genes; WHO International Standard for SARS-CoV-2 [8]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits | For comprehensive genomic analysis of pathogens from specimens, enabling variant identification and transmission tracking. | Kits integrated with specialized transport systems that stabilize nucleic acids [12]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Pre-Analytical Troubleshooting Guide

Q: My laboratory is rejecting viral specimens for degradation. What are the most likely causes? A: Specimen degradation is frequently caused by errors in temperature control during transport or using an incorrect transport medium. Ensure you are using a validated universal transport medium (UTM) and maintaining the recommended temperature chain. For molecular testing, if virus culturing is not required, consider using a transport medium that inactivates the virus but preserves nucleic acid integrity.

Q: I am getting unexpectedly low biomarker recovery from patient plasma samples. What pre-analytical factors should I investigate? A: Focus on transport temperature and timing. Several studies indicate that cold gel packs (4°C) provide stability comparable to dry ice for many biomarkers during a 24-hour transport window, while room temperature can cause significant degradation of labile biomarkers like FVIII. Also verify that processing occurs within 1 hour of collection and that freeze-thaw cycles are minimized.

Q: My coagulation test results, particularly for FV and FVIII, are inconsistent. What specific pre-analytical variables most affect these factors? A: FV and FVIII are exceptionally labile. Adhere to strict storage timelines: for FVIII activity, do not exceed 2 hours at room temperature or 4 hours refrigerated. For longer storage, freeze plasma at ≤ -75°C, as storage at -15 to -25°C leads to significant activity loss (>15% change) within one month for FV and two months for FVIII.

Temperature Stability Guide

Q: What is the acceptable transport duration for specimens on cold gel packs? A: For a panel of inflammatory, coagulation, and endothelial dysfunction biomarkers, transport on cold gel packs (4°C) for 24 hours showed minimal effects on precision (difference ≤7% compared to -80°C control).

Q: How stable are viral samples in universal transport medium at room temperature? A: Stability varies by pathogen, but high-quality UTMs can maintain specimen integrity for 48 to 72 hours at 20–25°C for many common viruses. One study showed no significant decrease in viral RNA concentration for HSV-2, echovirus, influenza A, and adenovirus after 7 days at 20–22°C.

Q: What are the critical temperature limits for labile coagulation factors? A: Based on recent evidence, FV and FVIII require stricter temperature control than other factors. The table below summarizes key stability findings.

Table 1: Stability of Labile Coagulation Factors Under Different Storage Conditions

| Factor | Room Temperature (18-25°C) | Refrigerated (2-8°C) | Frozen (-15 to -25°C) | Frozen (≤ -75°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FV | Stable for 5h (<15% change) | Stable for 5h (<15% change) | Unstable after 1 month (>15% change) | Stable for 4 months (<15% change) |

| FVIII | Stable for only 3h (<15% change) | Stable for only 4h (<15% change) | Unstable after 2 months (>15% change) | Stable for 4 months (<15% change) |

| Other Factors (FII, FVII, FIX, FX, FXI, FXII, FXIII) | Stable for 5h (<15% change) | Stable for 5h (<15% change) | Stable for 4 months (<15% change) | Stable for 4 months (<15% change) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Transport Temperature on Biomarker Stability

Objective: To determine the effects of transport temperature conditions on biomarker concentrations in specimens processed within 1 hour of collection.

Materials:

- Blood collection tubes (lithium heparin, sodium citrate, K2EDTA)

- Styrofoam shippers

- Temperature monitoring devices

- Dry ice, cold gel packs (4°C)

- -80°C freezer

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect blood via venipuncture or indwelling catheters (discarding first 10 mL). Centrifuge all specimens at 1300g for 10 minutes at 18–25°C within 1 hour of collection.

- Aliquoting: Aliquot plasma into 0.5mL cryovials.

- Temperature Simulation: Place cryovials in specimen boxes under four conditions:

- Control: Direct placement at -80°C

- Dry ice: Packaged in Styrofoam with dry ice (-79°C) for 24h

- Cold gel packs: Packaged with gel packs (4°C) for 24h

- Room temperature: Packaged without cooling (21°C) for 24h

- Storage: After 24h transport simulation, measure temperature and store all boxes at -80°C until batch analysis.

- Analysis: Measure biomarkers across signaling domains (inflammation, hemostasis, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress) using standardized assays.

Key Findings: Transport on cold gel packs (4°C) showed ≤7% difference in mean biomarker concentrations compared to -80°C control, making it a feasible alternative to dry ice for many biomarkers.

Protocol 2: Assessing Viral Transport Media Efficiency

Objective: To compare viral recovery rates from different transport media under varying temperature conditions.

Materials:

- Universal Transport Medium (UTM)

- M4-RT transport medium

- Flocked swabs

- Viral stocks (Influenza A, RSV, HSV, Adenovirus)

- Cell culture systems

Methodology:

- Sample Inoculation: Spike transport media with standardized viral loads (e.g., 10^6.4 TCID50 of Influenza A).

- Temperature Conditions: Incubate inoculated media at 4°C, 20-22°C, and 37°C.

- Time Points: Assess viral recovery at 24h, 48h, 72h, and 96h.

- Recruitment: Inoculate cell cultures with stored samples and observe for cytopathic effect.

- Molecular Detection: Perform real-time PCR to quantify viral nucleic acid preservation.

Key Findings: UTM demonstrated superior recovery of RSV after 96h compared to M4-RT. No significant decrease in viral RNA concentration was observed at 20–22°C for 7 days for multiple viruses.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the difference between Viral Transport Medium (VTM) and Universal Transport Medium (UTM)? A: While closely related, VTM is designed specifically for viral samples, while UTM has a broader formulation that may support both viral and bacterial specimen transport. Always verify compatibility with your specific testing platform.

Q: How long can samples remain in transport medium before processing? A: Most high-quality transport media maintain sample integrity for 24-72 hours, with some molecular preservation solutions extending stability to 30 days at ambient temperatures. Always consult the manufacturer's Instructions for Use for specific time-temperature limitations.

Q: What are the most common reasons for specimen rejection in viral testing? A: A 2025 study of 35,673 referred specimens found the top rejection reasons were:

- Hemolysis (28.6%)

- Insufficient volume (22.5%)

- Mislabeling (9.5%)

- Clotted specimens (8.0%)

Q: Why is the "pre-pre-analytical" phase receiving increased attention? A: Studies show most laboratory errors occur before samples reach the lab. The "pre-pre-analytical" phase - including test ordering, patient identification, sample collection, and transportation - is now recognized as critical for accurate diagnostic results. As one expert notes, "good samples make good assays."

Q: What specific components make an effective viral transport medium? A: An effective UTM typically contains:

- Buffer salts and HEPES to maintain neutral pH (7.3 ± 0.2)

- Protein stabilizers like gelatin or bovine serum albumin

- Cryoprotectants such as sucrose and glutamic acid

- Antimicrobial agents to inhibit bacterial and fungal contaminants

- pH indicator (e.g., phenol red) to identify potential contamination

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Pre-Analytical Workflow

Diagram 2: Specimen Integrity Decision Framework

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Viral Specimen Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Transport Medium (UTM) | Preserves viral and bacterial pathogen integrity during transport | Validated for 48h stability at 4°C or 20-25°C; compatible with molecular diagnostics |

| Flocked Swabs | Superior sample collection and release | Avoid cotton tips which can inhibit PCR; use synthetic tips for optimal recovery |

| Cold Gel Packs (4°C) | Maintain temperature during transport | Effective alternative to dry ice for many biomarkers during 24h transport |

| Dry Ice (-79°C) | Ultra-low temperature transport | Required for labile compounds; hazardous material requiring special training |

| Virus-Inactivating Media | Inactivates virus while preserving nucleic acids | Essential for safe transport during outbreaks; not suitable for culture |

| Leibovitz-Emory Medium | Charcoal-based transport medium | Superior recovery of herpesviruses compared to Amies media |

| Richards Transport Medium | Complex nutrient medium | Demonstrated longer half-life for HSV-2 at 22°C compared to other media |

Understanding Viral Pathogenesis to Guide Specimen Selection

FAQs on Specimen Selection and Pathogenesis

How does viral pathogenesis influence the choice of specimen type for diagnostic testing?

Viral pathogenesis—the process by which a virus causes illness in a host—directly determines where the virus replicates and which body sites contain the highest viral loads at different stages of infection. Consequently, understanding pathogenesis is critical for selecting a specimen that will yield a positive result if the patient is infected.

For example, respiratory viruses like influenza and SARS-CoV-2 primarily replicate in the respiratory tract, making upper respiratory specimens such as nasopharyngeal (NP) or nasal swabs the most appropriate for detection [14]. In contrast, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) can be found in blood, urine, or genital lesions, depending on the clinical syndrome [15]. Collecting a specimen from the wrong site, or at the wrong time in the infection cycle, is a common cause of false-negative results.

What is the optimal timing for specimen collection relative to symptom onset?

The timing of collection is crucial because viral shedding often correlates with the onset of symptoms. For many acute viral infections, the period of peak shedding is brief.

- General Rule: Specimens for virus isolation should ideally be collected within the first 4 days after symptom onset, as virus shedding typically decreases rapidly after this period. Virus cultures are generally not productive for specimens collected more than 7 days after illness begins [15].

- Considerations: Testing too early (during the incubation period) or too late (when the immune system has cleared the virus) can result in false negatives [16]. For instance, in flavivirus infections like Dengue or Zika, the short duration of viremia and low viral loads can restrict the detection window for viral RNA [17].

Why is specimen type critical for differentiating flaviviruses like Dengue, Zika, and West Nile?

Accurate diagnosis of flaviviruses is challenging due to significant antibody cross-reactivity between Dengue (DENV), Zika (ZIKV), and West Nile (WNV) viruses in serological assays [17]. Therefore, the choice of specimen and test method is paramount for differential diagnosis.

Nucleic Acid Tests (NATs) are the standard for confirmation, but their success depends on collecting the right specimen when viral RNA is present. The table below outlines preferred specimens and key challenges for these viruses.

Table 1: Specimen Considerations for Key Flaviviruses

| Virus | Primary Transmission | Preferred Specimen(s) for NAT | Key Diagnostic Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dengue (DENV) | Aedes mosquitos | Serum, Plasma [18] | Short duration of viremia, four serotypes complicating immunity and detection [17]. |

| Zika (ZIKV) | Aedes mosquitos | Serum, Urine, Semen | Significant antibody cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses, particularly DENV [17]. |

| West Nile (WNV) | Culex mosquitos | Serum, Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Asymptomatic infections are common; cross-reactive antibodies can lead to misdiagnosis [17]. |

What are the consequences of improper specimen handling and storage?

Improper handling during the pre-analytical phase is a major source of laboratory errors and can compromise specimen integrity, leading to inaccurate results [16].

- Time and Temperature: Many viruses are stable at 4°C for 2-3 days, but for longer storage, they should be kept at -70°C [15]. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles can degrade nucleic acids and should be avoided [16] [18].

- Inhibitors: Specimens like feces contain endogenous inhibitors (e.g., hemoglobin, lactoferrin) that can interfere with nucleic acid amplification tests. Proper extraction and purification protocols are necessary to remove these substances [16] [19].

- Collection Materials: Using the wrong swab type (e.g., calcium alginate or swabs with wooden shafts) can introduce substances that inactivate viruses or inhibit molecular tests [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Nucleic Acid Yield from Viscous Specimens

Problem: Low DNA/RNA yield during automated extraction from viscous samples like plasma, serum, or saliva.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Incomplete Lysis: Viscous samples can prevent uniform mixing with the lysis buffer.

- Solution: Ensure thorough pipette mixing or vortexing to homogenize the sample and lysis buffer. Visually confirm that a complete vortex forms [19].

- Protein Clumping: Protein-rich samples can cause magnetic bead clumping during binding and wash steps.

- Solution: Use Proteinase K during lysis to degrade proteins and improve viral particle lysis. Adding an extra wash step can also help reduce contamination and improve purity [19].

- Pipetting Errors: High viscosity makes accurate pipetting difficult.

- Solution: Use wide-bore pipette tips designed for viscous liquids to prevent clogging and ensure accurate volume transfer [19].

- Inefficient Binding: Nucleic acids may not bind efficiently to the purification matrix.

- Solution: Visually inspect that magnetic particles remain fully suspended during the binding step, as complete suspension is necessary for efficient binding [19].

Inconsistent Molecular Results from Clinical Specimens

Problem: Variable or inaccurate quantitative PCR results from clinical samples, such as serum.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Choice of Extraction Method: Different RNA extraction methods have variable efficiencies.

- Solution: Silica-based adsorption methods (e.g., spin columns, magnetic beads) are generally more robust and less affected by high serum protein content than liquid-phase partition methods [18]. Always validate the chosen method for your sample type.

- Specimen Integrity: The stability of viral RNA in the specimen or lysate can be time-sensitive.

- Solution: Process specimens promptly. While intact virus in serum may be stable for ~2 hours at 25°C, viral RNA in lysis buffer can be stable for up to 5 days [18]. Adhere to validated storage conditions.

- Presence of Inhibitors: Endogenous substances in the specimen can inhibit enzymatic reactions in PCR.

Data Presentation

Specimen Collection Guidelines for Common Viral Pathogens

The following table summarizes collection guidelines for various specimen types based on the target virus and its pathogenesis.

Table 2: Virology Specimen Collection Guidelines for Diagnostic Testing

| Specimen Type | Common Target Viruses | Collection Device & Minimum Volume | Transport Time & Temp | Key Pathogenesis & Collection Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood (Plasma/Serum) | CMV, HIV, Dengue, WNV | Heparin or EDTA tube; 8-10 mL [15] | Room Temperature [15] | Collect during acute phase for viremia. Do not refrigerate. Anticoagulants like heparin can inhibit PCR [16]. |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | Enteroviruses, HSV, Mumps | Sterile leak-proof tube; 1.0 mL [15] | Immediately at 4°C [15] | Collected via lumbar puncture for viruses causing meningitis/encephalitis. |

| Nasopharyngeal Swab | SARS-CoV-2, Influenza, RSV | Synthetic swab (rayon/dacron) in viral transport media (UTM) [14] | Immediately at 4°C [15] | Do not use calcium alginate or wooden-shafted swabs [14]. For SARS-CoV-2, NP specimen is preferred [14]. |

| Feces | Enteroviruses, Adenoviruses, Rotavirus | Sterile, leak-proof container; at least 2 g [15] | 4°C [15] | High biomass and PCR inhibitors; homogenization is often required [19]. |

| Vesicular Swab | HSV, VZV (Chickenpox) | Synthetic swab in UTM [15] | Immediately at 4°C [15] | Sample fresh vesicles; older crusted lesions may not contain viable virus. Vigorously sample the base of the lesion [15]. |

| Urine | CMV, Adenovirus, Mumps | Sterile container; 5 mL [15] | 4°C [15] | Collect midstream clean-catch. Successive daily specimens maximize CMV recovery [15]. |

| Tissue | Various (e.g., HSV, CMV) | Specimen placed in UTM [15] | 4°C [15] | Sample tissue adjacent to affected area. Never submit a swab rubbed over the surface [15]. |

Impact of Pre-analytical Variables on Viral RNA Quantification

Quantitative data from research on dengue virus (DENV) highlights how pre-analytical choices directly impact measured viral load.

Table 3: Impact of Pre-analytical Factors on DENV RNA Quantification

| Pre-analytical Variable | Effect on Viral RNA Recovery | Experimental Findings & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Method | Significant variation in efficiency | Silica-based methods were less affected by high serum proteins than liquid-phase partition (Trizol). Recovery with Trizol was improved by adding a co-precipitant and reducing serum proteins [18]. |

| Freeze-Thaw Cycles | No significant effect observed | Repeated freeze-thaw cycles did not significantly affect the recovery of viral RNA from clinical samples [18]. |

| Storage of Intact Virus in Serum | Stability is time/temperature dependent | Intact DENV in serum remained stable for up to 2 hours at 25°C [18]. |

| Storage of RNA in Lysis Buffer | Improved stability | Viral RNA from sera stored in lysis/binding buffer was stable for up to 5 days [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Automated Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction from Challenging Specimens

This protocol outlines a generalized method for automating the extraction of viral NA from viscous (e.g., plasma, saliva) or complex (e.g., feces) samples, based on silica magnetic particle technology [19].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Serum/Plasma: Centrifuge to remove cellular debris and contaminants. Use wide-bore tips for pipetting to handle viscosity and avoid clots [19].

- Saliva: Centrifuge to remove food particles and debris. The use of Proteinase K is highly recommended due to saliva's high protein content and viscosity. Sample dilution can also facilitate mixing [19].

- Feces: Homogenize a small portion (10-20% mass/volume) in lysis buffer. High biomass can lead to pipetting errors and inhibitor carryover; using less sample can improve consistency. Physical disruption (bead beating) and Proteinase K can increase extraction efficiency [19].

2. Lysis:

- Incubate the prepared sample with a lysis buffer containing salts (e.g., guanidine thiocyanate) and detergents (e.g., SDS) to denature proteins and release nucleic acids from the viral capsid. The addition of Proteinase K at this stage improves lysis efficiency, especially for protein-rich samples [19].

3. Binding:

- Mix the lysate with a binding buffer and silica-coated magnetic particles. Nucleic acids bind selectively to the silica surface under high-salt conditions.

- Critical Step: Ensure proper mixing to keep magnetic particles suspended, allowing nucleic acids to contact the binding surface. Inefficient mixing is a primary cause of low yield [19].

4. Washing:

- Move the magnetic particles with bound NA through two or more wash buffers. The washes remove impurities, including proteins, salts, and PCR inhibitors.

- Critical Step: Visually confirm that particles are fully resuspended in each wash buffer. Any remaining clumps will not be effectively washed. For difficult samples, an additional wash step may be necessary [19].

5. Elution:

- Resuspend the washed magnetic particles in a low-salt elution buffer (e.g., Tris-EDTA buffer or nuclease-free water). This disrupts the silica-NA interaction, releasing pure nucleic acids into the solution [19].

Troubleshooting Control: Always include a manual extraction control when developing or troubleshooting an automated method to benchmark performance and identify problems [19].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Magnetic Beads | Solid phase for binding nucleic acids from lysates. | Core component of many automated extraction systems. Beads are moved by magnets for wash and elution steps [20]. |

| Lysis Buffer | Disrupts viral envelope/capsid and inactivates nucleases. | Typically contains chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine thiocyanate) and detergents (e.g., SDS) to release NA [19]. |

| Proteinase K | Broad-spectrum serine protease. | Degrades proteins and nucleases, improving lysis of viral particles and reducing bead clumping in protein-rich samples (e.g., saliva, plasma) [19]. |

| Binding Buffer | Creates high-salt conditions promoting NA binding to silica. | Optimized for specific silica surfaces to maximize NA recovery and purity. |

| Wash Buffer | Removes contaminants (proteins, salts, inhibitors) from bound NA. | Usually contains alcohol and buffers. Inefficient washing is a common source of PCR inhibitors in the final eluate [19]. |

| Elution Buffer | Low-ionic-strength solution (e.g., TE buffer, water) to release pure NA from beads. | Essential for downstream analytical performance. |

In viral diagnostic research, the pre-analytical phase encompasses all steps from test selection and patient preparation to sample collection and transport, before the sample is analyzed [21] [22]. This phase is the most vulnerable to error in the entire laboratory testing process. Evidence indicates that pre-analytical errors contribute to 60-70% of all laboratory mistakes [21]. In the specific context of viral diagnostics, such errors can directly lead to false-negative results, where a true infection is missed, or compromise the integrity of research data, ultimately derailing drug development and scientific conclusions [21] [22]. This guide details common pitfalls, troubleshooting methodologies, and preventive strategies to safeguard the quality of specimen choice research.

Understanding the scale and distribution of errors is the first step toward mitigation. The following tables summarize key data on error frequency and primary sources.

Table 1: Distribution of Laboratory Errors by Phase

| Phase of Testing Process | Approximate Contribution to Total Laboratory Errors |

|---|---|

| Pre-analytical Phase | 60% - 70% [21] |

| Analytical Phase | Low percentage (precise figure not provided, but described as having seen a "ten-fold reduction") [22] |

| Post-analytical Phase | Not specified in data |

Table 2: Common Pre-analytical Errors Leading to Sample Rejection

| Type of Error | Relative Contribution to Pre-analytical Errors |

|---|---|

| Hemolyzed Samples | 40% - 70% [21] |

| Insufficient Sample Volume | 10% - 20% [21] |

| Clotted Sample | 5% - 10% [21] |

| Use of Wrong Container | 5% - 15% [21] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

A Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology

When a viral diagnostic assay yields an unexpected negative result or compromised data, a structured approach is essential. The following workflow, adapted from general laboratory troubleshooting principles, provides a logical pathway for investigation [23] [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our viral PCR tests are consistently returning false negatives despite using validated kits. The pre-analytical steps are performed by clinical staff outside our direct control. Where should we focus our investigation? [21] [22]

- A: This is a classic "pre-pre-analytical" phase problem. Your investigation should prioritize:

- Sample Collection Technique: Improper swabbing (e.g., insufficient force or time, incorrect anatomical site like nasal vs. nasopharyngeal) can drastically reduce viral load. Inappropriate choice of collection swab (e.g., cotton-tipped with inhibitory compounds) can degrade the virus or inhibit PCR [21].

- Sample Storage & Transport: Viral RNA is labile. Check if the time between collection and processing exceeds stability limits. Verify that transport temperatures adhere to protocol (e.g., room temperature vs. frozen on dry ice). Ensure transport media are correctly formulated and not expired [22].

- Patient Identification and Labeling: Misidentified samples can lead to false negatives for infected patients. Implement electronic labeling with barcodes and mandate labeling in the patient's presence [21].

Q2: We are seeing high variability and degraded RNA in our research samples, making viral load quantification unreliable. What are the most likely causes? [21] [25]

- A: Degradation and variability strongly point to issues in sample handling and preparation.

- Hemolysis and Contamination: Hemolyzed samples from difficult venipuncture contain nucleases that degrade nucleic acids. Check for pink/red discoloration in plasma. Also, confirm samples are not collected from an arm with an active IV line, causing contamination or dilution [21].

- Inconsistent Processing Delays: Even small variations in the time from collection to centrifugation and freezing can significantly impact RNA integrity. Standardize and strictly enforce processing time windows for all samples [22].

- Reagent and Equipment Check: Ensure that RNA stabilization reagents (e.g., RNAlater) are added promptly and have not expired. Verify that centrifuges are calibrated to achieve the correct g-force for plasma separation and that freezer temperatures are consistently maintained at -80°C [26] [25].

Q3: We added a new, rapid sample preparation kit to our workflow, but now our positive controls are failing. How do we determine if the kit is the problem? [23] [24]

- A: To isolate the variable, design a controlled experiment:

- Run Parallel Controls: Process your well-characterized positive control sample using both the old and new kits simultaneously. Include a no-template control (NTC) for each to rule out contamination.

- Check Kit Components: Review the storage conditions and expiration dates of all kit components, especially enzymes. Test the kit with a different, known-viable sample to see if the problem is specific to your control or universal.

- Consult the Vendor: Inquire if other users have reported similar issues and request performance data for the specific kit lot number. This data can help determine if you received a faulty batch [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Nasopharyngeal Swab Collection for Viral RNA Detection

Principle: To ensure consistent collection of adequate viral material from the nasopharynx while preserving RNA integrity for downstream molecular analysis.

Reagents and Materials:

- Sterile nasopharyngeal swab (synthetic tip, plastic or wire shaft)

- Appropriate viral transport media (VTM)

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Gloves, gown, face shield/N95 mask

- Cryovials for storage

- -80°C Freezer

Procedure:

- Patient Preparation: Explain the procedure to the patient. Seat them comfortably with their head tilted slightly back.

- Swab Insertion: Gently insert the swab into the nostril, following the palate (not upwards) toward the ear until resistance is met. The distance from the nose to the ear lobe is typically sufficient.

- Sample Collection: Rotate the swab gently and leave it in place for 5-10 seconds to absorb secretions.

- Swab Removal: Slowly remove the swab while continuing to rotate it.

- Transfer to VTM: Immediately place the swab tip into the vial containing VTM. Snap the scored portion of the swab shaft to fit the vial and close the lid securely.

- Labeling: Label the tube with at least two patient identifiers (e.g., full name and date of birth) in their presence.

- Transport and Storage: Place the sample in a sealed transport bag and keep it at 2-8°C if processing within 48 hours. If processing is delayed beyond 48 hours, freeze at -80°C or below. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Blood-Tinged Swab: May indicate overly forceful collection, which can lead to inhibition in PCR. Note the observation and consider re-collection if the test result is negative and clinical suspicion remains high.

- Incorrect Swab Type: Calcium alginate or cotton-tipped swabs can inhibit PCR reactions and are not recommended.

Protocol 2: Verification of Sample Integrity Prior to Viral RNA Extraction

Principle: To assess the quality of a clinical sample and the extracted nucleic acid, ensuring they are suitable for reliable viral detection and quantification.

Reagents and Materials:

- Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop) or Fluorometer (Qubit)

- Agarose gel electrophoresis system

- Bioanalyzer or TapeStation (optional, for higher resolution)

- Ethidium Bromide or SYBR Safe dye

- DNA/RNA Ladder

Procedure: A. Visual Inspection of Sample:

- Inspect the plasma/serum for hemolysis (pink/red), lipemia (milky), or icterus (yellow). Document any abnormalities. Hemolyzed samples should be noted and may require re-collection for quantitative studies [21].

B. Nucleic Acid Quantification and Quality Control:

- Spectrophotometry: Use 1-2 µL of extracted RNA to measure absorbance at 260nm and 280nm.

- The A260/A280 ratio should be ~2.0 for pure RNA. A lower ratio suggests protein contamination.

- The A260/A230 ratio should be >2.0. A lower ratio suggests contamination by salts or organic compounds.

- Fluorometry: For a more accurate quantification of RNA concentration, use RNA-specific fluorescent dyes.

- Electrophoresis: Run 100-500 ng of RNA on a denaturing agarose gel.

- Intact RNA will show sharp, clear ribosomal RNA bands (28S and 18S for eukaryotic RNA from host cells). The 28S band should be approximately twice the intensity of the 18S band.

- Degraded RNA will appear as a smear down the lane, with absent or faint ribosomal bands.

Interpretation: A sample with low RNA yield, poor purity ratios, or a degraded electrophoretic profile is suboptimal for viral detection and may lead to false negatives. The experiment should be repeated with a new, properly handled sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Viral Specimen Research

| Item | Function & Importance in Pre-analytical Phase |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Tip Swabs | Collect specimen without inhibiting molecular assays. Cotton swabs can contain PCR inhibitors. |

| Viral Transport Media (VTM) | Preserves viral integrity and prevents desiccation during transport from clinic to lab. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Immediately inutes RNases upon contact, preserving viral RNA at room temperature for longer periods, crucial for field studies. |

| Cell Lysis Buffer | The primary component of nucleic acid extraction kits, it disrupts the viral envelope and host cells to release RNA. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Used to reconstitute or dilute nucleic acids; ensures no ambient nucleases degrade the sample. |

| Positive Control Material | Inactivated virus or synthetic RNA used to verify that the entire workflow, from extraction to detection, is functioning correctly. |

Visual Guide to Error Pathways

The following diagram illustrates how a single pre-analytical error can propagate through the research workflow, ultimately leading to compromised data and erroneous conclusions.

Syndrome-Driven Specimen Selection: A Methodological Guide for Viral Detection

Troubleshooting Guide: Specimen Collection & Pre-Analytical Errors

FAQ: What are the most common pre-analytical errors that lead to specimen rejection?

Pre-analytical errors occur before the sample is analyzed and are the most frequent source of problems in laboratory testing [16] [27]. The following table summarizes common reasons for specimen rejection and strategies to prevent them.

Table 1: Common Pre-analytical Errors and Prevention Strategies

| Error Category | Specific Reason for Rejection | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Quality | Hemolysis [28] [27] | Ensure proper drawing and transferring techniques; avoid forceful aspiration. |

| Insufficient sample volume [28] [27] | Train collectors on required volumes for specific tests; use appropriate collection devices. | |

| Clotted specimen [28] [27] | Invert collection tubes gently as recommended after collection. | |

| Sample Handling & Transport | Delayed transport time [16] [29] | Transport specimens to the laboratory as quickly as possible; minimize duration at ambient temperatures. |

| Broken cold chain [28] | Ensure proper temperature maintenance during transport and storage; use appropriate coolers. | |

| Labeling & Documentation | Unlabeled or mislabeled specimen [28] [27] | Label specimens immediately after collection at the patient's bedside. |

| Missing or incorrect request form [28] [27] | Implement electronic ordering systems with barcoding; double-check forms before sending samples. | |

| Container Issues | Inappropriate container [28] | Use only approved specimen containers and transport media [30]. |

| Contaminated specimen [28] | Maintain aseptic technique during collection. |

FAQ: My respiratory virus detection results are inconsistent. Could the sampling method be at fault?

Yes, the sampling method and technique are critical for consistent results. While a meta-analysis of 13 studies found no overall statistical difference in sensitivity between nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) and nasal washes/aspirates for most viruses, the choice of method should be guided by the specific context [31] [32]. Inconsistencies can arise from several factors:

- Anatomical Sampling Site: The nasopharynx (the uppermost part of the throat behind the nose) is the preferred site as it harbors higher viral loads compared to the anterior nasal cavity or oropharynx [31] [29]. One study in adults with acute pharyngitis found NPS had a significantly higher sensitivity (74%) compared to both nasal wash (49%) and oropharyngeal swab (49%) [33].

- Swab Type and Material: The use of flocked swabs is strongly recommended. Flocked swabs, which have perpendicular nylon fibers, have been shown to collect and release respiratory epithelial cells more effectively than traditional fibrous swabs (e.g., rayon or cotton), leading to superior specimen quality and pathogen recovery [30] [29] [34]. Swabs with wooden shafts should be avoided as they can contain substances that inhibit nucleic acid amplification [29].

- Transport Medium: Specimens for nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) should be placed in an appropriate liquid transport medium, such as Viral Transport Medium (VTM) or Universal Transport Medium (UTM), to maintain pathogen viability and nucleic acid integrity during transport [30] [29]. While dry swabs can be used if necessary, they may result in lower sensitivity and are not ideal [29].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Studies

Detailed Methodology for Head-to-Head Comparison of Sampling Techniques

The following protocol, adapted from a 2013 study comparing swabs and washes, provides a robust framework for evaluating the sensitivity of different respiratory specimen collection methods [33].

Objective: To compare the sensitivity of nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS), nasal washes (NW), and oropharyngeal swabs (OPS) for the detection of respiratory viruses using real-time PCR.

Sample Collection Workflow: The diagram below illustrates the sequential collection and processing of triple samples from a single patient.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions & Key Materials:

- Flocked Nasopharyngeal Swabs: For NPS collection (e.g., FLOQSwabs [30]).

- Rayon Swabs: For OPS collection [33].

- Viral Transport Medium (VTM): For swab storage and transport (e.g., UTM [30]).

- Sterile Normal Saline: For performing nasal wash.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit: For purifying viral RNA/DNA (e.g., QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin kit [33]).

- Real-time PCR Assays: Primers and probes for target respiratory viruses (e.g., Influenza A/B, RSV, Rhinovirus, etc.) [33].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Patient Enrollment: Recruit patients presenting with acute respiratory symptoms (e.g., within 3 days of onset). Obtain informed consent and ethical approval.

- Specimen Collection Order: Collect specimens from each patient in the following consecutive order to minimize cross-contamination and interference [33]:

- Oropharyngeal Swab (OPS): Use a rayon swab to vigorously sample the posterior oropharyngeal wall and tonsillar areas.

- Nasopharyngeal Swab (NPS): Insert a flexible flocked swab into one nostril along the nasal floor until resistance is met at the nasopharynx. Rotate the swab 2-3 times and hold for 5 seconds before withdrawal.

- Nasal Wash (NW): Instill 2.5-5 ml of sterile normal saline into the other nostril using a syringe. After a few seconds, aspirate the fluid or have the patient expel it into a sterile container. Repeat if the volume retrieved is less than 2 ml.

- Specimen Handling:

- Place the OPS and NPS into separate tubes containing 1-3 mL of VTM/UTM. Break or cut the swab shaft to secure it in the tube.

- Transfer the NW fluid to a sterile container.

- Store all specimens at 4°C and transport to the laboratory within 6 hours of collection.

- Upon receipt in the laboratory, store specimens at -80°C until batch testing.

- Laboratory Testing:

- Extract nucleic acids from 200 µL of each sample (OPS, NPS, NW) according to the manufacturer's instructions for the extraction kit.

- Perform real-time PCR (e.g., TaqMan assays) for a panel of common respiratory viruses. Define a positive result based on a pre-determined cycle threshold (Ct) value (e.g., Ct ≤ 35) [33].

- Data Analysis:

- Define a "true positive" patient as one for which any of the three specimen types (NPS, NW, or OPS) tests positive for a virus.

- Calculate the sensitivity for each method as: (Number of positives by that method / Total number of "true positive" patients) * 100.

- Compare the sensitivities statistically using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, with a p-value of < 0.05 considered significant.

Performance Data & Technical Specifications

Comparative Sensitivity of Sampling Methods

The table below synthesizes quantitative data on the sensitivity of different sampling methods from clinical studies. It is important to note that sensitivity can vary based on the virus, patient age, and detection technology.

Table 2: Comparative Sensitivity of Respiratory Specimen Collection Methods

| Specimen Type | Overall Sensitivity (vs. Consensus Standard) | Pathogen-Specific & Contextual Findings | Key Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal Swab (NPS) | 74% (in adults with pharyngitis) [33] | Higher for certain viruses: 100% for Rhinovirus vs. 60% for NW; 75% for Adenovirus vs. 17% for NW [33].No overall difference for 8 major viruses in meta-analysis [31].One study favored NPS for Influenza H1N1(2009) [31]. | Advantages: Easier and faster to collect; less invasive and better patient tolerance [30] [34]; easier to store and transport [30].Disadvantages: Requires training for proper technique; sensitive to sampling depth and technique. |

| Nasal Wash (NW) / Aspirate | 49% (in adults with pharyngitis) [33] | Comparable to NPS for many viruses (RSV, Influenza, Coronavirus) in meta-analysis [31]. | Advantages: Collects a larger volume, potentially sampling a broader area.Disadvantages: More unpleasant for patients; requires specialized equipment/suction; more training needed; processing can be more complex [33] [34]. |

| Oropharyngeal Swab (OPS) | 49% (in adults with pharyngitis) [33] | Lower viral loads in the oropharynx compared to the nasopharynx [34]. | Advantages: Simple to collect.Disadvantages: Generally lower sensitivity for most respiratory viruses; not recommended as a sole sample type [29]. |

| Saliva | 88% (meta-analysis) [29] | Sensitivity is lower and more variable than NPS [29]. | Advantages: Non-invasive and easy to collect.Disadvantages: Variable sensitivity; potential for inhibitors. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Respiratory Virus Detection Research

| Item | Function/Application | Recommendation & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Flocked Swabs | Sample collection from the nasopharynx. | Use swabs with nylon flocked fibers (e.g., FLOQSwabs). They exhibit superior specimen collection and release of cellular material compared to traditional cotton or rayon swabs, enhancing test sensitivity [30] [29] [34]. |

| Universal Transport Medium (UTM) | Transport and storage of swab specimens. | Use FDA-cleared transport media like UTM. It maintains viral viability and nucleic acid integrity for up to 48 hours at room or refrigerated temperatures, ensuring specimen quality during transport to the lab [30]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Purification of viral RNA/DNA from clinical samples. | Use automated or manual kits designed for viral nucleic acids (e.g., QIAamp kits [33]). Proper extraction is critical for removing PCR inhibitors and obtaining high-quality template for amplification. |

| Multiplex NAAT Panels | Simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory pathogens. | Employ commercial or laboratory-developed multiplex PCR panels. These are the gold standard for sensitive and comprehensive detection of a wide range of viruses in a single test [29] [34] [35]. |

Fundamental Concepts: Plasma, Serum, and Leukocytes in Viral Diagnostics

What are the fundamental differences between plasma, serum, and leukocyte specimens for detecting systemic viral infections?

Plasma is the liquid component of whole blood that contains clotting factors, obtained by collecting blood in anticoagulant-containing tubes (e.g., EDTA, heparin) and centrifuging to separate cells. Serum is the liquid component remaining after blood has clotted, lacking clotting factors, obtained by collecting blood in tubes without anticoagulant, allowing it to clot, then centrifuging. Leukocytes (white blood cells) are the cellular components obtained from the buffy coat after density gradient centrifugation of anticoagulated blood [36] [37].

These specimens differ significantly in their applications for viral detection. Plasma and serum contain free-floating viruses, viral antigens, and antibodies, making them ideal for nucleic acid tests (e.g., PCR), antigen assays, and serology. Leukocytes host cell-associated viruses (e.g., HIV, cytomegalovirus) and are used for viral culture or PCR when detecting latent or intracellular infections [36] [37]. The choice of anticoagulant is critical: EDTA tubes are preferred for molecular testing as heparin can inhibit PCR amplification [16] [37].

Table: Comparison of Blood-Derived Specimen Types for Viral Diagnosis

| Specimen Type | Components | Primary Viral Targets | Common Tests | Collection Tube |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Liquid blood fraction with clotting factors | Free viruses, viral RNA/DNA, antigens | Quantitative PCR, antigen tests | EDTA, citrate |

| Serum | Liquid blood fraction without clotting factors | Antibodies (IgM, IgG), some free viruses | ELISA, Western blot, neutralization assays | Serum separator tubes (SST) |

| Leukocytes | White blood cells (buffy coat) | Cell-associated viruses | Viral culture, DNA PCR | EDTA with density gradient centrifugation |

Specimen Selection Guide

How do I select the appropriate specimen type for different systemic viral infections?

Specimen selection depends on the viral pathogenesis, target analyte (virus vs. antibody), and stage of infection. The table below outlines evidence-based recommendations for common systemic viral infections [36] [37].

Table: Specimen Selection Guide for Systemic Viral Infections

| Virus | Preferred Specimen(s) | Detection Method | Clinical Utility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | Plasma (EDTA), Leukocytes | Quantitative RNA PCR, DNA PCR | Diagnosis, viral load monitoring, treatment efficacy | DNA PCR from leukocytes for infant diagnosis; EDTA plasma for viral load [37] |

| Hepatitis B & C | Serum, Plasma | Antigen ELISA, RNA PCR, Antibody ELISA | Diagnosis, viral load, chronic infection monitoring | Serum for serology; plasma for molecular detection [36] |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | Leukocytes, Plasma, Whole Blood | PCR, Viral Culture, pp65 antigenemia | Detection in immunocompromised, congenital infection | Leukocytes for culture/antigenemia; plasma/serum for PCR in disseminated disease [37] |

| Arboviruses | Serum, Plasma, CSF | IgM/IgG ELISA, PCR | Acute infection diagnosis | PCR from serum/plasma in early infection; serology after 5-7 days [37] |

Specimen Collection & Processing Protocols

What are the standardized protocols for collecting and processing plasma, serum, and leukocyte specimens?

Plasma Collection (EDTA Tube)

- Collection: Draw 2-10 mL whole blood into EDTA tube [37]

- Mixing: Gently invert tube 8-10 times immediately after collection

- Processing: Centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C within 2 hours of collection [38]

- Separation: Carefully transfer supernatant (plasma) to sterile cryovial without disturbing buffy coat

- Storage: Freeze at -80°C if not testing immediately; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles

Serum Collection (Clot Tube)

- Collection: Draw 2-10 mL whole blood into serum separator tube (SST) [37]

- Clotting: Allow blood to clot at room temperature for 30-60 minutes

- Processing: Centrifuge at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Separation: Transfer clear serum to sterile cryovial, avoiding red blood cells

- Storage: Freeze at -80°C for long-term storage; stable at 4°C for 24-48 hours

Leukocyte Isolation (Density Gradient)

- Collection: Draw blood into EDTA tube (heparin can be inhibitory for PCR) [16]

- Dilution: Mix blood with equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Layering: Carefully layer diluted blood over Ficoll-Paque solution

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 800 × g for 30 minutes at 20°C with brake off

- Harvesting: Collect buffy coat (cloudy interface layer) containing leukocytes

- Washing: Wash cells twice with PBS and count cells for culture or lyse for DNA extraction

Troubleshooting Pre-Analytical Errors

What are the most common pre-analytical errors and how can they be prevented?

Pre-analytical errors account for the majority of laboratory errors in viral diagnostics [16]. The table below outlines common issues and evidence-based solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Pre-Analytical Errors

| Error Category | Specific Problem | Impact on Results | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen Collection | Hemolyzed sample | False negative PCR due to inhibitors | Proper venipuncture technique; avoid excessive force [16] |

| Insufficient blood volume | Erroneous viral load quantification | Verify minimum volume requirements (2 mL for adults) [37] | |

| Time & Temperature | Delayed processing >2h (RT) | RNA degradation, false negative PCR | Process within 2h; keep on ice (4°C) if delayed [38] |

| Improper freezing/thawing | Viral infectivity loss, nucleic acid degradation | Snap-freeze at -80°C; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [38] [36] | |

| Container & Additives | Heparin anticoagulant | PCR inhibition | Use EDTA tubes for molecular tests [16] [37] |

| Sample contamination | False positive PCR | Use sterile techniques; separate pre-and post-PCR areas [16] | |

| Biological Variables | Antiretroviral therapy | Undetectable viral load (false negative) | Document patient medication history [16] |

| Early infection window | Undetectable antibodies | Consider PCR in early symptomatic phase [37] |

Experimental Methodologies & Protocols

What are the detailed experimental protocols for detecting viruses in these specimens?

Quantitative PCR for Viral Load from Plasma/Serum Principle: This method quantifies viral nucleic acids through amplification with virus-specific primers and fluorescent detection [39].

Protocol:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use commercial silica-membrane kits (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit) with 140μL plasma/serum input

- Reverse Transcription: For RNA viruses, convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase with random hexamers

- qPCR Setup: Prepare reaction mix with:

- 5μL extracted nucleic acids

- 10μL 2× master mix

- 1μL each forward/reverse primer (10μM)

- 0.5μL probe (10μM)

- Nuclease-free water to 20μL

- Amplification: Run on real-time PCR instrument with cycling conditions:

- 50°C for 2 min (UNG incubation)

- 95°C for 10 min (activation)

- 45 cycles of: 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 min

- Quantification: Calculate viral copies/mL using standard curve from quantified controls

ELISA for Antiviral Antibodies from Serum Principle: This immunoassay detects virus-specific antibodies through enzyme-linked colorimetric detection [40] [39].

Protocol:

- Coating: Adsorb viral antigen to polystyrene microplate wells (100μL/well, 4°C overnight)

- Blocking: Add 200μL blocking buffer (1% BSA in PBS) for 1 hour at 37°C

- Sample Incubation: Add 100μL diluted (1:100) serum samples in duplicate, incubate 1-2 hours at 37°C

- Detection: Add 100μL enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-human IgG/IgM), incubate 1 hour at 37°C

- Substrate: Add 100μL chromogenic substrate (TMB), incubate 30 minutes in dark

- Stopping: Add 50μL stop solution (1N H₂SO₄)

- Reading: Measure absorbance at 450nm; calculate cutoff value (mean negative controls + 0.150)

Viral Culture from Leukocytes Principle: This method detects infectious virus through inoculation of permissive cell lines and observation of cytopathic effects [36].

Protocol:

- Cell Preparation: Seed appropriate cell line (e.g., peripheral blood mononuclear cells for HIV) in 24-well plates

- Inoculation: Add isolated leukocytes (1×10⁶ cells/mL) to cell monolayer

- Incubation: Maintain at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 2-21 days depending on virus

- Monitoring: Observe daily for cytopathic effects (cell rounding, syncytia formation)

- Confirmation: Confirm viral presence by immunofluorescence or PCR

Research Reagent Solutions

What are the essential research reagents and materials for working with these specimens?

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Detection from Blood Specimens

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | Plasma and leukocyte collection; prevents coagulation | K₂EDTA or K₃EDTA; 2-10 mL draw volume |