Strategies for Viral Diagnostic Contamination Risk Reduction: From Prevention to Validation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to mitigate viral contamination risks in diagnostic and bioprocessing environments.

Strategies for Viral Diagnostic Contamination Risk Reduction: From Prevention to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to mitigate viral contamination risks in diagnostic and bioprocessing environments. It explores the foundational sources and impacts of contamination, details advanced methodological applications for detection and monitoring, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies for existing protocols, and discusses rigorous validation and comparative analysis of emerging technologies. By synthesizing current best practices and novel approaches, this guide aims to enhance the reliability, safety, and integrity of viral diagnostics and biologics manufacturing.

Understanding the Sources and Impact of Viral Contamination

Defining Adventitious and Endogenous Viral Contaminants

FAQs on Viral Contaminants

1. What is the key difference between an adventitious and an endogenous viral agent?

- Adventitious Agents are microorganisms that are unintentionally introduced into the manufacturing process of a biological product. They are foreign contaminants that can be introduced via raw materials like cell substrates, bovine serum, or porcine trypsin [1]. Examples include viruses, bacteria, mycoplasma, and TSE agents.

- Endogenous Viral Agents are parts of viral genomes that have become integrated into the genome of the cell line itself. They are a inherent part of the cell substrate. A key example is the presence of retrovirus-like particles in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells, which cause no visual change to the cells but can pose a potential risk [2].

2. Why are some viral contaminations, like endogenous retroviruses, difficult to detect?

Some viral contaminations do not cause a visible cytopathic effect (cell damage) [2]. Instead, the viral genome integrates into the host cell's DNA as a provirus, providing no visual evidence of contamination under a microscope. This "silent" contamination requires specific molecular techniques for detection [2].

3. What are the primary sources of adventitious virus introduction in bioproduction?

Cell cultures can become contaminated through three primary means [2]:

- Primary Contamination: The source of the cells was already infected (e.g., from an animal or human donor).

- Contaminated Raw Materials: The use of infected reagents like bovine serum or porcine trypsin.

- Cross-Contamination: From other infected cell cultures in the same lab or via animal passage.

4. What are the major historical incidents of viral contamination in vaccines?

Several notable events have shaped regulatory oversight [1]:

- Simian Virus 40 (SV40) in Polio Vaccine: Discovered in 1960, this monkey virus contaminated early batches of polio vaccine produced in rhesus monkey kidney cells [1].

- Porcine Circovirus (PCV1) in Rotavirus Vaccine: PCV1 viral DNA was detected in a licensed rotavirus vaccine, traced back to the use of porcine trypsin during manufacture [1].

5. What are "No Template Controls" and why are they critical in viral diagnostics?

A No Template Control (NTC) is a well in a qPCR plate that contains all the reaction components except for the DNA template [3]. It is a critical control to monitor for contamination. If amplification occurs in the NTC, it signals that one of the reagents or the laboratory environment is contaminated with the target DNA, which could lead to false-positive results in the actual samples [3].

Troubleshooting Guide for Contamination Prevention and Detection

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution / Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification in No Template Control (NTC) [3] | Contaminated reagents or aerosolized amplicons in the lab environment. | Replace all suspected reagents. Establish separate pre- and post-amplification laboratory areas. Use uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) in qPCR master mixes to degrade carryover contaminants [3]. |

| Unexplained, Inconsistent Test Results | Low-level, non-cytopathic viral contamination that doesn't cause cell death [2]. | Implement regular, sensitive molecular screening assays (e.g., PCR) for a broad panel of potential viral contaminants, even in the absence of visible cell damage. |

| Persistent Contamination After Cleaning | Ineffective surface decontamination. | Decontaminate work surfaces and equipment with a fresh 10-15% bleach solution (sodium hypochlorite), allowing 10-15 minutes of contact time before wiping. Follow with 70% ethanol cleaning for routine use [3]. |

| Suspected Raw Material Contamination | Adventitious viruses introduced via animal-derived reagents (e.g., serum, trypsin) [2] [1]. | Source raw materials from qualified suppliers with robust testing regimens. Implement and archive samples for retrospective testing. Incorporate viral clearance/inactivation steps in the production process where possible [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Viral Detection and Risk Mitigation

Protocol 1: Establishing a Contamination-Free qPCR Workflow

This protocol outlines best practices to prevent DNA contamination in sensitive molecular assays like qPCR, which is crucial for accurate viral detection [3].

- Physical Separation of Work Areas: Establish dedicated, separate rooms for pre-amplification (reagent preparation, sample setup) and post-amplification (analysis of PCR products) activities. These areas should have independent equipment, lab coats, and consumables [3].

- Unidirectional Workflow: Personnel must not move from post-amplification areas back to pre-amplification areas on the same day without a complete change of personal protective equipment (PPE) [3].

- Use of Aerosol-Reduction Tips: Always use filtered, aerosol-resistant pipette tips to prevent cross-contamination between samples [3].

- UNG Treatment: Use a qPCR master mix containing uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) and substitute dUTP for dTTP in the reaction. Incubate reactions at room temperature before thermocycling to allow UNG to enzymatically degrade any uracil-containing carryover DNA from previous amplifications [3].

- Rigorous Surface Decontamination: Regularly clean all work surfaces and equipment with 70% ethanol. In case of spills or suspected contamination, use a fresh 10% bleach solution [3].

Protocol 2: Archiving for Retrospective Adventitious Agent Testing

This methodology is critical for investigating contamination events and leveraging new technologies for risk reduction [1].

- Sample Identification: Identify and label samples from all critical stages of production, including cell bank seeds, bulk harvests, final product lots, and all biological raw materials (e.g., serum, trypsin) [1].

- Secure Storage: Archive samples in a dedicated, secure storage facility (e.g., -80°C freezer or vapor-phase liquid nitrogen) with controlled access and environmental monitoring.

- Documentation and Traceability: Maintain detailed records that provide full traceability, linking each archived sample to its source, production batch, and date. This is essential for a thorough root cause analysis if a contaminant is discovered post-market [1].

- Retrospective Analysis: In the event of a newly identified contaminant risk (e.g., a previously unknown virus), use archived samples to determine the origin, duration, and scope of the contamination. This allows for a precise risk assessment and targeted corrective actions [1].

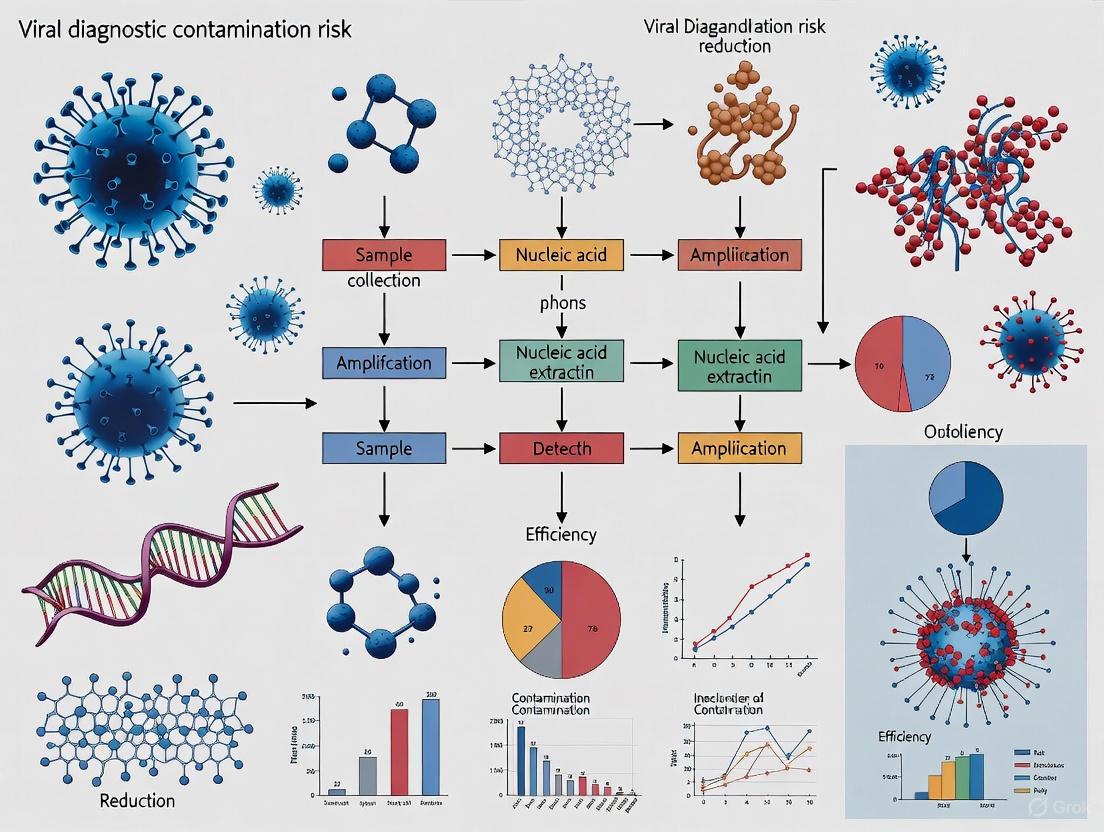

Visualizing Viral Contaminant Pathways and Detection Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for defining, identifying, and managing different types of viral contaminants in bioprocessing.

Viral Contaminant Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details essential materials and their functions in the context of preventing and detecting viral contaminants.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Contamination Risk Reduction |

|---|---|

| Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) [3] | An enzyme used in qPCR master mixes to prevent false positives by degrading carryover contamination from previous amplification products. |

| Aerosol-Resistant Filtered Pipette Tips [3] | Physical barriers that prevent aerosols and liquids from contaminating the pipette shaft, thereby reducing cross-contamination between samples. |

| Bovine Serum [2] [1] | A common growth medium supplement for cell cultures that is a potential source of adventitious viruses (e.g., bovine viral diarrhea virus) and requires rigorous testing. |

| Porcine Trypsin [2] [1] | A reagent used to passage adherent cell cultures that can be a source of viral contaminants like porcine parvovirus or porcine circovirus (PCV1). |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) [3] | A potent chemical decontaminant used at 10-15% dilution to effectively destroy DNA and inactivate viruses on laboratory surfaces and equipment. |

| Mycoplasma Testing Kits | Essential for routine screening of cell cultures for mycoplasma contamination, which is another major class of adventitious agent [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: Cell Bank Contamination

Q: Our cell bank has failed a critical sterility test. What are the immediate steps we should take to contain the issue and identify the root cause?

A: A failed sterility test requires immediate and systematic action. The following workflow outlines the critical response and investigation path.

Immediate Actions:

- Quarantine: Immediately quarantine the entire affected cell bank lot and any working cell banks (WCBs) derived from it to prevent use in production or experiments [5].

- Documentation: Freeze all related documentation and initiate a deviation report as per your quality management system [6].

Root Cause Analysis: Investigate potential failure points across the entire lifecycle:

- Testing Process: Verify the sterility testing procedure itself. Confirm that bacteriostasis and fungistasis testing was performed prior to sterility testing to rule out sample matrix inhibition, which can cause false negatives [7]. Review reagent quality and analyst training.

- Cell Line History & Raw Materials: Scrutinize the complete history of the cell line, focusing on exposure to animal-derived raw materials like fetal bovine serum (FBS) or trypsin. The absence of Certificates of Analysis (CoAs) for these materials is a major risk factor for introducing microbial and viral contaminants [8] [7].

- Manufacturing Environment & Equipment: Audit the aseptic processing environment. Check records for environmental monitoring (viable and non-viable particulates), equipment sterilization validation (e.g., autoclave, SIP cycles), and cleaning validation of stainless-steel equipment to rule out biofilm formation [9] [6].

- Personnel & Aseptic Technique: Review gowning qualification records and environmental monitoring data linked to operator activities. Human error is a prevalent source of contamination, often due to breaks in aseptic technique [9] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Raw Material Contamination

Q: We suspect our cell culture media is a source of low-level, persistent microbial contamination. How can we confirm this and prevent recurrence?

A: Suspect raw materials require a rigorous qualification process. The logical flow below details the confirmation and prevention strategy.

Confirmation Steps:

- In-house Testing: Do not rely solely on the supplier's Certificate of Analysis (CoA). Perform your own tests on the suspect material batch for bioburden, sterility, and mycoplasma using compendial methods [5] [10].

- Process Simulation: Use the suspect media in a small-scale culture run with a non-critical cell line and closely monitor for pH shifts, turbidity, and microbial growth.

Prevention Strategies:

- Supplier Qualification: Audit your supplier's quality management system. Ensure they provide comprehensive CoAs that include testing for sterility, endotoxins, and mycoplasma, and Certificates of Origin for materials of biological origin [10].

- Material Upgrade: Transition from research-grade to GMP-grade raw materials for clinical development and commercial manufacturing. GMP-grade materials have stricter controls and testing protocols [10].

- Media Adaptation: Where possible, adapt your cell lines to serum-free and chemically defined media. This eliminates the high-risk variable of animal sera, a common source of adventitious agents like viruses and mycoplasma [8] [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Human Operator Contamination

Q: An audit identified inconsistent aseptic practices among our staff. What is the most effective way to retrain personnel and reduce this contamination risk?

A: Inconsistent aseptic technique is a critical finding that requires a holistic approach combining training, monitoring, and process design.

Corrective and Preventive Actions:

- Re-training and Qualification: Implement a mandatory, hands-on re-training program for all personnel entering the aseptic processing area. This must include practical demonstrations in a mock environment. Follow this with a formal gowning qualification and aseptic technique qualification, where personnel perform media fills (process simulations) to prove their competency. Their access should be contingent on passing these qualifications [9] [6].

- Enhanced Monitoring: Increase the frequency of environmental monitoring during operations, including surface and air sampling, and settle plates. Correlate this data with specific personnel and shifts to identify patterns and target further training [9] [6].

- Procedure and Design Review: Simplify complex manual procedures to reduce intervention points. Implement closed processing systems and single-use technologies (e.g., sterile tubing welders, pre-sterilized single-use bags) to minimize direct operator contact with the product and process fluids [11] [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical tests required for a GMP-compliant Master Cell Bank (MCB)?

A: A comprehensive testing panel is required to ensure the safety and purity of an MCB. The tests are designed to detect microbial, viral, and cellular contaminants. The following table summarizes the key testing categories and methods.

Table 1: Critical Characterization Tests for a GMP Master Cell Bank (MCB)

| Test Category | Specific Assays & Methods | Key Target Contaminants / Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Sterility Testing | Compendial methods (e.g., direct inoculation, membrane filtration) [7]. | Bacteria, fungi, and mold. |

| Mycoplasma Testing | Compendial culture methods (28 days) or validated rapid methods (e.g., PCR, fluorescence) [5] [7]. | Mycoplasma and Acholeplasma species. |

| Viral Safety Testing | In vitro assay: Inoculation on indicator cell lines (e.g., Vero, MRC-5) observed for CPE, HAD, HA [7]. | Broad spectrum of unknown viral contaminants. |

| In vivo assay: Inoculation into suckling/adult mice, guinea pigs, embryonated eggs [7]. | Viruses not detectable by in vitro methods. | |

| Species-specific tests: e.g., Antibody Production Tests (MAP, RAP) for rodent cells [7]. | Specific viruses (e.g., LCMV, Hantaan). | |

| Retrovirus Testing: Reverse transcriptase (RT) assays, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [7]. | Endogenous and adventitious retroviruses. | |

| Identity & Genetic Stability | Karyology, Isoenzyme analysis, DNA fingerprinting (STR), Sequencing [8] [7]. | Confirmation of cell line identity and genetic integrity. |

Q2: Beyond sterility, what are the key quality attributes to check in critical raw materials like cell culture media?

A: While sterility is paramount, other quality attributes are critical for consistent cell growth and product quality.

Table 2: Key Quality Attributes for Critical Raw Materials (e.g., Cell Culture Media)

| Quality Attribute | Importance & Impact | Typical Testing Method |

|---|---|---|

| Endotoxin Level | Pyrogenic; can elicit immune responses in cells and patients. | LAL (Limulus Amebocyte Lysate) test. |

| Performance | Directly impacts cell growth, viability, and productivity. | Small-scale cell culture growth study. |

| pH & Osmolality | Critical biochemical parameters for cell health. | pH meter, osmometer. |

| Chemical Composition | Consistency in components (e.g., glucose, amino acids) is key for process reproducibility. | HPLC, GC-MS. |

| Viral Safety | Ensures no adventitious viruses are introduced via raw materials. | Supplier's virus validation studies; use of viral-inactivated materials (e.g., gamma-irradiated FBS) [10]. |

Q3: Our viral diagnostic assays are highly sensitive to cross-contamination. What practical lab design and workflow solutions can we implement?

A: Implementing strict procedural and physical controls is essential to prevent amplicon or sample cross-contamination.

- Physical Separation: Establish physically separated, dedicated rooms or areas for pre-amplification (sample prep, PCR setup) and post-amplification (PCR product analysis) activities. Implement unidirectional workflow and dedicated equipment for each area [9].

- Environmental Controls: Use HEPA-filtered air, positive air pressure in cleanrooms, and UV lights in biosafety cabinets to reduce airborne contaminants [9].

- Use of Closed Systems: Employ closed-system processing technologies, such as single-use bioreactor bags and sterile tube welders/sterile connectors. This minimizes the need for open manipulations and reduces the risk of contamination from the environment and human operators [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| GMP-Master Cell Bank (MCB) | A fully characterized, GMP-compliant bank provides a consistent and secure starting material, ensuring the identity, purity, and safety of the cell line used in production or testing [8] [7]. |

| Chemically Defined Media | Media formulations with fully known components eliminate the variability and adventitious agent risk associated with animal-derived sera like FBS, enhancing process consistency and safety [8] [10]. |

| Viral-Inactivated Serum | When serum is necessary, using gamma-irradiated FBS mitigates the risk of introducing viral contaminants [7]. |

| Single-Use Systems (SUS) | Pre-sterilized, disposable bioreactor bags, tubing, and filters eliminate the risk of cross-contamination between batches and remove the need for cleaning validation, reducing operational complexity [12]. |

| Rapid Mycoplasma Detection Kits | PCR- or fluorescence-based kits allow for faster detection of mycoplasma contamination compared to the 28-day compendial culture method, enabling quicker decision-making [5] [7]. |

| Validated Disinfectants | Using disinfectants with validated efficacy (e.g., sporicidal, bactericidal) and following a rotating regimen prevents the development of resistant microbial strains on surfaces [11]. |

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers mitigate viral contamination risks in cell culture-based bioprocesses, supporting broader thesis research on viral diagnostic contamination risk reduction.

Viral Contamination Troubleshooting FAQ

Q: What are the most critical yet often overlooked viral contaminants in cell culture? A: Two critical contaminants are the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and ovine herpesvirus 2 (OvHV-2). EBV is highly ubiquitous (infecting ~98% of humans) but is often not a primary safety priority because its detection methods are well-established. In contrast, OvHV-2 represents a more critical and complex challenge due to its ability to infect a wide range of organs and over 33 animal species, making its detection crucial for cross-species cell culture safety [13] [14] [15].

Q: Why is OvHV-2 contamination particularly problematic for bioprocessing? A: OvHV-2 poses a significant challenge in research and bioprocessing settings because its broad species tropism increases the risk of contaminating cell cultures derived from various animals. Furthermore, comprehensive and robust detection methodologies specific to OvHV-2 are not as established as for other viruses, creating a gap in safety protocols [14] [15].

Q: What are the primary sources of viral contamination in a bioprocess? A: Viral infections can originate from three main sources, requiring vigilance throughout the entire workflow [13]:

- Contaminated Cell Lines: The initial cells used in the process may already harbor a latent or active virus.

- Contaminated Raw Materials: Reagents, media, or supplements introduced into the culture can be a source.

- Process Breakdowns: Failures in production or purification procedures can introduce contamination.

Q: How can we differentiate between active infection and incidental presence of EBV in cell cultures? A: Distinguishing causality is a common diagnostic challenge. Relying solely on qualitative DNA detection (e.g., positive PCR) is insufficient. It is essential to employ supporting parameters such as viral load quantification (where a high load suggests active infection), analysis of CSF/serum ratios, and detection of intrathecal antibody synthesis to confirm a virus's active role in contamination [16].

Detection Methodologies for Featured Viral Contaminants

The table below summarizes established and emerging detection methods for key viral contaminants, providing a protocol foundation for your research.

Table 1: Detection Methods for EBV and OvHV-2 in Cell Culture

| Virus | Applicable Cell Lines | Preferred Detection Methods | Protocol Details and Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) | B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-LCLs), 293 human embryonic kidney (293HEK) [14] | PCR: Detects EBV DNA with high sensitivity and specificity [14].In situ hybridization (ISH): Detects EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBERs) for localization [14].EBNA detection: Identifies EBNA proteins via ELISA or Western blot [14]. | PCR protocols are well-established and can distinguish between latent and lytic forms. ISH is ideal for confirming the presence and cellular location of the virus within a culture [13] [14]. |

| Ovine Herpesvirus 2 (OvHV-2) | Ovine peripheral blood lymphocytes [14] | PCR: The main tool for detection; however, methods are less universally established than for EBV [14].Advanced Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing (HTS) and single-cell analysis are emerging for revealing viral diversity [13]. | The primary challenge is the lack of a universally validated, robust detection method. Emerging technologies like HTS are recommended to close this gap [13] [14]. |

| Minute Virus of Mice (MVM) | Information on MVM was not available in the consulted sources. | Information on MVM was not available in the consulted sources. | Information on MVM was not available in the consulted sources. |

Advanced and Emerging Detection Technologies

The field of viral detection is rapidly evolving. The following workflow illustrates how traditional and modern methods can be integrated into a comprehensive contamination screening strategy.

Workflow Explanation:

- Traditional Methods provide an accessible first pass but may lack sensitivity [17].

- Molecular Methods (PCR) offer targeted, sensitive, and quantitative data crucial for determining active infection versus incidental presence [16] [14].

- Advanced Sequencing (HTS/mNGS) is powerful for uncovering unexpected contaminants and viral diversity, directly addressing gaps in understanding for viruses like OvHV-2 [13] [17].

- Emerging Technologies like CRISPR-based diagnostics and AI-assisted analysis represent the future of rapid, precise, and accessible testing, even in point-of-care settings [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and materials for implementing the detection protocols discussed.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Viral Contamination Detection

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function in Contamination Detection |

|---|---|

| PCR Assay Kits | Detect specific viral DNA with high sensitivity. Well-established for EBV; development is needed for robust OvHV-2 detection [13] [14]. |

| High-Throughput Sequencing (HTS) | Provides a comprehensive, unbiased screen for known and unknown viral contaminants, revealing viral diversity within cultures [13]. |

| In-situ Hybridization Probes | Locate viral RNA (e.g., EBERs in EBV) within cells, confirming infection and providing spatial context [14]. |

| Antibodies for Viral Antigens | Detect viral proteins (e.g., EBNA, VCA) via ELISA, Western Blot, or immunofluorescence to confirm active viral replication [14]. |

| Cell Line Authentication Kits | Perform STR profiling to ensure cell line identity and purity, a foundational quality control measure that mitigates risk [15]. |

Comparative Risk Analysis of Viral Contaminants

Understanding the relative risk profiles of different contaminants helps in allocating resources effectively. The following diagram summarizes the critical attributes of EBV and OvHV-2.

Risk Profile Explanation:

- EBV is managed effectively due to mature diagnostics, allowing it to be categorized as a lower-tier risk despite its ubiquity [13] [14].

- OvHV-2 presents a higher and more complex risk due to its broad host range and the lack of universally robust detection methods, labeling it a critical concern that requires more research and protocol development [13] [14] [15].

FAQ: Implementing a Viral Vigilance Strategy

Q: What is the single most important shift in mindset for preventing viral contamination? A: Move from a one-time check to a philosophy of continuous "viral vigilance." Monitoring is not a single step but an ongoing process integrated throughout the entire bioprocess ecosystem and workflow, from raw material qualification to final product purification [13].

Q: Are there new technologies that can help with the challenge of incidental viral detection? A: Yes. Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) is particularly valuable in complex diagnostic situations. However, when it detects a ubiquitous virus like EBV, it is critical to follow up with quantitative PCR (viral load) and other supporting clinical parameters to accurately determine if the virus is a causative agent or an incidental bystander [16].

The Economic and Clinical Consequences of Contamination Events

Contamination events in biomedical research and biopharmaceutical manufacturing pose severe risks, extending far beyond the laboratory bench. These incidents can derail diagnostic accuracy, compromise therapeutic safety, and inflict substantial economic losses. For researchers and drug development professionals, a proactive understanding of these consequences is fundamental to viral diagnostic contamination risk reduction. This technical support center provides a comprehensive resource to troubleshoot, prevent, and manage these risks, framing them within the critical context of their broader economic and clinical impact.

The table below summarizes the multifaceted consequences of contamination events, highlighting the direct and indirect costs across research and commercial production.

Table 1: Consequences of Contamination Events in Research and Biomanufacturing

| Impact Category | Economic Consequences | Clinical Consequences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research & Development | - Invalidated experimental data, leading to project delays and wasted funding [18].- Retraction of published studies, damaging scientific credibility.- Loss of precious or irreplaceable cell lines [18]. | - Preclinical findings based on contaminated systems can misdirect entire therapeutic development pipelines.- Incorrect diagnostic assay development due to compromised reagents. | |

| Biologics Manufacturing | - Production shutdowns; a single viral contamination can cost millions of dollars to resolve [19] [20].- Loss of entire product batches, leading to drug shortages and revenue loss [19].- Costs associated with root cause investigation, corrective actions, and facility decontamination [19]. | - Patients may not receive critical therapies (e.g., recombinant proteins, vaccines) [19] [20].- Risk of transmitting adventitious viruses to patients, a historic issue with blood and plasma products [19]. | |

| Broader Socioeconomic Effects | - Supply chain disruptions for medicines and vaccines [21] [22].- Reduced investor confidence and financing gaps, as seen during the Ebola outbreak where gaps exceeded \$600 million in affected countries [21].- Macroeconomic shocks, including decreased GDP growth and government tax revenues [21] [23]. | - Public health crises and loss of trust in health systems. | - Long-term health burdens from untreated conditions due to overwhelmed or disrupted healthcare services, as observed during the West Africa Ebola epidemic [21]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs: Contamination Identification and Control

Q1: My cell culture medium is turning yellow and I see moving particles under the microscope. What is this and what should I do?

- Identification: This is a classic sign of bacterial contamination. Under the microscope, you may observe large numbers of moving particles, often described as a "quicksand" effect [24].

- Action:

- For a mild contamination, wash the cells with PBS and treat with a high concentration of antibiotics (e.g., 10× penicillin/streptomycin). Note that this is often a temporary solution [24].

- For heavy contamination, the recommended course of action is to discard the culture immediately [24]. Thoroughly disinfect the incubator, water baths, and biosafety cabinet with appropriate disinfectants like 70% ethanol or sodium hypochlorite (bleach) to prevent spread [24] [18].

Q2: I suspect mycoplasma contamination in my cells. How can I confirm this, and how do I eradicate it?

- Identification: Mycoplasma does not cause medium turbidity or color change. Signs include slow cell growth, abnormal morphology, and under a microscope, tiny black dots may be visible. Staining with a DNA-specific dye (e.g., DAPI or Hoechst) and fluorescence microscopy can reveal filamentous patterns on the cell surface [18].

- Confirmation: Use a commercial mycoplasma detection kit. Common methods include PCR-based detection, DNA staining, or microbial culture [24] [18].

- Eradication: Treat cultures with a commercially available mycoplasma removal agent (e.g., 40607ES01/03/08 [24]). Be aware that treatments can be cytotoxic and may not always be 100% effective. Quarantine treated cells and reconfirm they are mycoplasma-free after several passages. The safest option for non-critical cultures is often to discard and start anew [24] [18].

Q3: What are the most common sources of viral contamination in biologic manufacturing, and how are they controlled?

- Sources: Common sources include the original cell bank, animal-derived reagents (e.g., fetal bovine serum), and during production via raw materials or operator error [19]. Prevalent viral contaminants include Murine Minute Virus (MMV), Vesivirus 2117, and Cache Valley virus [19].

- Risk Control: A multi-layered quality risk management approach is essential [25]. This includes:

- Thorough testing of cell banks and raw materials for viruses.

- Incorporating viral clearance steps into the production process, such as virus filtration (using filters with pores ≤ 20 nm), solvent/detergent treatment, and low-pH incubation [19].

- Defining and validating "functionally closed" systems in biomanufacturing to prevent adventitious agent ingress [25].

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Risk Reduction

Protocol 1: Routine Mycoplasma Detection by DNA Staining

Principle: This method uses a fluorescent dye to bind DNA. Mycoplasma, which adheres to the cell surface, will appear as particulate or filamentous fluorescence outside the host cell nuclei.

Materials:

- Mycoplasma Detection Kit (e.g., MycAway Plus, Cat. No. 40615ES25 [24])

- Cell culture of interest (grown on a sterile coverslip in a dish)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Fixative (e.g., Methanol or Acetic acid)

- DNA stain (e.g., DAPI or Hoechst stain)

- Antifade mounting medium

- Fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

- Grow test cells to 50-80% confluency on a sterile coverslip in a culture dish. Include a known positive control.

- Aspirate the medium and wash the cells gently with PBS.

- Fix the cells by adding fixative (e.g., cold methanol) for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Aspirate the fixative and allow the coverslip to air dry completely.

- Prepare the DNA stain according to the kit instructions or manufacturer's recommendation.

- Add the stain to the fixed cells and incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes.

- Gently rinse the coverslip with PBS to remove unbound stain.

- Mount the coverslip onto a microscope slide with antifade mounting medium.

- Visualize under a fluorescence microscope with the appropriate filter set. Examine the cytoplasm and areas between cells for punctate or filamentous staining.

Protocol 2: Viral Clearance Validation Study for Downstream Processing

Principle: This model experiment is used to validate that a manufacturing purification step (e.g., chromatography or virus filtration) can effectively remove and/or inactivate viral contaminants.

Materials:

- Scale-down model of the purification step (e.g., a small-scale chromatography column or filter)

- Process intermediate sample

- Model viruses (e.g., MMV for small, non-enveloped viruses; X-MuLV for large, enveloped viruses)

- Cell lines for viral titrations (e.g., Vero cells, A9 cells)

- Cell culture media and reagents

Procedure:

- Spiking: Spike a known quantity of the model virus (e.g., >10^6 virus particles/mL) into the process intermediate sample.

- Processing: Run the spiked sample through the scaled-down purification step under conditions that mimic the full-scale manufacturing process.

- Collection: Collect the product fraction (the output).

- Titration: Determine the viral titer in both the starting spiked material and the product fraction using a plaque assay or TCID50 assay on permissive cell lines.

- Calculation: Calculate the log reduction value (LRV) using the formula:

- LRV = Log10 (Virus titer in starting material) - Log10 (Virus titer in product)

- A high LRV (typically ≥ 4 logs) indicates a robust and effective viral clearance step [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for assessing and controlling viral contamination risk in a production or research setting.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Contamination Control and Detection

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Mycoplasma Detection Kit | For routine monitoring of cell cultures for mycoplasma contamination via PCR, DNA staining, or enzymatic activity. Essential for validating cell line health. | 40615ES25 [24] |

| Mycoplasma Removal Reagent | A formulated reagent used to treat and eliminate mycoplasma from contaminated cell cultures without requiring cell passage through animals. | 40607ES01 [24] |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin (P/S) | A broad-spectrum antibiotic solution used in cell culture media to prevent bacterial contamination. Overuse can lead to antibiotic-resistant strains. | N/A in sources |

| Amphotericin B | An antifungal agent used to prevent and treat yeast and mold contamination. Can be toxic to cells at high concentrations. | N/A in sources |

| Virus Removal Filter | A filter with precisely sized pores (e.g., 20 nm or smaller) used in bioprocessing to physically remove viral particles from biological products [19]. | N/A in sources |

| Surface Disinfectant (e.g., Ethanol, Benzalkonium Chloride) | For decontaminating work surfaces, equipment, and incubators. 70% ethanol is common; stronger disinfectants are used for fungal outbreaks [24] [18]. | 40605ES02 [24] |

Implementing Robust Detection and Prevention Methodologies

The 'Prevent, Detect, Remove' Framework for Viral Safety

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Viral Safety Issues

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upstream Prevention | Bioreactor contamination with adventitious viruses [26] | High-risk raw materials (e.g., plant-origin glucose, animal-derived sera) [26] | Implement high temperature short time (HTST) pasteurization for glucose solutions; Use virus-retentive filters on cell culture media [26]. |

| Contamination from raw materials [27] | Poorly characterized raw materials or sourcing from multiple vendors [27] | Use chemically defined, non-animal origin media and recombinant supplements; Rigorous supplier evaluation and raw material testing [26] [27]. | |

| Viral Detection | Inadequate detection sensitivity [27] | Limitations in assay methods or insensitivity of cell-based assays [27] | Employ multiple, orthogonal detection methods (e.g., in vitro assays, PCR); Test cell banks, raw materials, and process intermediates [28] [29] [26]. |

| Downstream Removal | Inconsistent viral clearance [27] | Over-reliance on a single clearance method; Process variability [27] | Implement robust, orthogonal downstream purification steps (inactivation + removal); Execute viral clearance validation studies [28] [29] [30]. |

| Cell Line Safety | Vulnerability to specific viruses (e.g., MVM) [26] | Use of standard, non-resistant cell lines [26] | Utilize genetically modified virus-resistant cell lines (e.g., MVM-resistant CHO cells) where available [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Prevention Strategies

Q: What are the highest-risk raw materials for introducing viral contamination in mAb production? A: Raw materials of plant-origin (like glucose) and animal-derived components (like bovine serum or trypsin) are considered high-risk [26]. Glucose is particularly risky due to its source in sugarcane or beet fields, which can attract virus-carrying rodents. Mitigation strategies include HTST pasteurization and using virus-retentive filters designed for cell culture media [26].

Q: How can we prevent contamination from the supply chain? A: A robust risk mitigation strategy involves [26] [27]:

- Sourcing and Evaluation: Carefully select and vet raw material suppliers. Understand the complexities and risks throughout the entire supply chain.

- Material Substitution: Replace high-risk, animal-derived components with lower-risk alternatives, such as chemically defined cell culture media and non-animal origin recombinant supplements.

- Proactive Treatment: Apply viral inactivation or removal methods (e.g., UV-C, HTST, virus-reduction filtration) to culture media or its components before use.

Detection and Testing

Q: What are the key testing points for detecting viral contamination in a bioprocess? A: A comprehensive testing regimen covers [28] [29] [26]:

- Cell Banks: Master and working cell banks.

- Raw Materials: Critical culture components prior to use.

- Process Intermediates: Unprocessed bulk harvests. This layered approach ensures contamination is identified as early as possible.

Q: Why can't we guarantee a biologic is absolutely free of viral contamination? A: The current state of technology precludes claiming absolute absence of viruses due to [27]:

- Inherent Risk: All biopharmaceutical production using mammalian components carries an inherent risk.

- Detection Limitations: Assays have limited sensitivity, and adventitious viruses can sometimes escape detection. Therefore, regulatory safety relies on a holistic strategy that combines prevention, detection, and robust removal/inactivation processes to assure patient safety [27].

Removal and Inactivation

Q: What is the regulatory expectation for demonstrating viral clearance? A: Regulatory guidelines (ICH Q5A) require viral clearance studies to demonstrate the manufacturing process's capability to remove and inactivate viruses [27]. These studies validate that specific downstream purification steps (e.g., virus filtration, low pH incubation) can effectively reduce viral load, providing a safety margin in case a contaminant is introduced upstream [28] [29] [27].

Q: Why is it important to use orthogonal methods for viral clearance? A: Orthogonal methods use different mechanisms to inactivate or remove viruses. For example, a process might combine a chemical method (low pH inactivation) with a physical method (virus filtration). This approach is critical because viruses have diverse characteristics, and using multiple, independent methods ensures broad clearance capability and protects against process variability [27].

Experimental Protocols for Viral Safety

Protocol 1: Viral Clearance Validation for a Downstream Step

Objective: To determine the log10 reduction value (LRV) of a specific purification step for a model virus.

Materials:

- Scale-down model of the purification step (e.g., chromatography column, virus filter, incubation tank)

- Model virus (e.g., Murine Leukemia Virus (MuLV) or another relevant virus from regulatory guidelines)

- Appropriate cell-based assay for quantifying infectious virus (plaque assay or TCID50)

Methodology [27]:

- Spiking: Spike a known quantity of the model virus (e.g., >10^6 infectious units) into the process intermediate material that is the input for the step being studied.

- Processing: Run the spiked material through the scaled-down purification step under defined operating parameters (e.g., flow rate, pressure, buffer conditions).

- Collection: Collect the output (product) from the step.

- Titration: Determine the infectious virus titer in both the spiked starting material and the output material using the cell-based assay.

- Calculation: Calculate the LRV using the formula:

LRV = Log10 (Virus Titer in Input Material) - Log10 (Virus Titer in Output Material)

Interpretation: A high LRV (e.g., >4 log10) indicates robust clearance capability for that model virus by the manufacturing step.

Protocol 2: HTST Pasteurization for Raw Material Risk Mitigation

Objective: To validate the effectiveness of high-temperature short-time (HTST) treatment in inactivating viruses in a raw material solution.

Materials:

- HTST pasteurization system

- High-risk raw material solution (e.g., glucose)

- Model virus with high physico-chemical resistance (e.g., Parvovirus)

- Virus titration assay

Methodology [26]:

- Preparation: Spike the raw material solution with a high titer of the model virus.

- Treatment: Subject the spiked solution to HTST treatment under validated conditions (specific temperature and time, e.g., 100°C for seconds).

- Cooling: Rapidly cool the treated solution.

- Analysis: Measure the infectious virus titer in the solution before and after HTST treatment.

- Control: Run a non-heated control sample in parallel to account for any non-thermal virus loss.

Interpretation: Successful validation shows a significant reduction in viral titer (high LRV) in the treated sample with no impact on the raw material's performance in cell culture.

Framework and Workflow Visualization

Viral Safety Framework Flow

Viral Clearance Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Viral Safety | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Virus-Retentive Filters [26] | Remove both enveloped and non-enveloped viruses from cell culture media or process intermediates. | Use filters designed for specific fluid types (media vs. product) to balance throughput and viral retention. |

| Chemically Defined Media [26] | Eliminates risk from animal-derived components; provides consistent, defined composition. | Supports cell growth and productivity while reducing adventitious agent risk. |

| Non-Animal Origin Recombinant Supplements [26] | Replaces high-risk materials like bovine serum or trypsin. | Critical for mitigating contamination originating from raw materials. |

| Virus Panel for Clearance Studies [27] | Used to validate the capacity of downstream steps to inactivate/remove diverse viruses. | Must include relevant (e.g., retroviruses) and challenging (e.g., parvoviruses) model viruses. |

| Model Viruses (e.g., MuLV, MVM) [27] | Serve as surrogates in viral clearance studies to demonstrate reduction capability. | Chosen based on size, envelope, and resistance to represent potential contaminants. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address specific issues encountered while using advanced detection tools, with a focus on reducing contamination risks in viral diagnostics.

PCR Troubleshooting FAQs

1. No or Low PCR Product Yield

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal Reaction Components | Verify all components were added. Check reagent expiration dates and avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting biological components [31] [32]. |

| Poor Template Quality/Quantity | Analyze DNA integrity via gel electrophoresis and check purity (A260/280 ratio ≥1.8). Use 1 pg–10 ng for plasmid DNA or 1 ng–1 µg for genomic DNA per 50 µL reaction [33] [31] [32]. Further purify template if contaminated with inhibitors [33] [34]. |

| Incorrect Annealing Temperature | Recalculate primer Tm and test an annealing temperature gradient starting 5°C below the lower Tm [33]. Lower the temperature in 2°C increments if too stringent [34]. |

| Insufficient Cycles or Extension Time | Increase cycle number (by 3-5 cycles, up to 40) for low-abundance targets [34]. Ensure extension time is sufficient for polymerase speed and amplicon length [31]. |

| Complex Template (e.g., GC-rich) | Use polymerases formulated for GC-rich templates and include GC enhancers or co-solvents like DMSO [33] [34] [35]. Increase denaturation temperature/time [35]. |

2. Multiple or Non-Specific Bands

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Annealing Temperature Too Low | Increase annealing temperature incrementally (e.g., in 2°C increments) to improve specificity [33] [34] [32]. |

| Poor Primer Design | Verify primers are specific, have no self-complementarity, and avoid GC-rich 3' ends. Redesign if necessary, following standard design rules [33] [32] [35]. |

| Excess Primer or Template | Optimize primer concentration (typically 0.1–1 µM). Reduce the amount of template DNA if too much was used [33] [32] [35]. |

| Premature Replication | Use a hot-start polymerase. Set up reactions on ice and use a preheated thermocycler [33] [35]. |

| Contamination | Use filter pipette tips, establish separate pre- and post-PCR work areas, and include a no-template control [33] [34] [32]. |

3. Sequence Errors in PCR Product

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Low-Fidelity Polymerase | Switch to a high-fidelity polymerase [33] [31] [35]. |

| Excessive Number of Cycles | Reduce the number of PCR cycles to minimize misincorporation errors [33] [31]. |

| Unbalanced dNTP Concentrations | Use fresh, equimolar dNTP mixes. Aliquot stocks to prevent degradation [33] [31] [35]. |

| High Mg²⁺ Concentration | Optimize and reduce Mg²⁺ concentration in the reaction [33] [35]. |

| Template DNA Damage | Limit UV light exposure when excising PCR products from gels. Start with a fresh, high-quality template [33] [31]. |

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Troubleshooting FAQs

1. What are the key considerations when choosing an NGS method for low viral load samples?

The optimal NGS method depends on the required sensitivity, genome coverage, and need for non-targeted detection. A recent European multicentre study comparing methods for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) genome characterization found significant performance differences [36].

Table: NGS Method Performance for Viral Genome Detection at Low Loads

| NGS Method | Sensitivity (Viral Load) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted Metagenomics | >10 IU/ml for some viruses, but failed for HBV in study [36] | Detects unexpected/novel viruses; unbiased approach [36]. | Low sensitivity; high host background; complex data analysis [36]. |

| Probe-Capture + Illumina | >1000 IU/ml (for full HBV genome) [36] | Detects multiple pre-defined pathogens; accommodates incidental virus detection [36]. | Higher cost; longer turnaround time; limits genome characterization near ends [36]. |

| PCR + Illumina | >200 IU/ml (for full HBV genome) [36] | Good sensitivity; well-established; high accuracy [36]. | Risk of contamination; limited to targeted regions [36]. |

| PCR + Nanopore | >10 IU/ml (for full HBV genome) [36] | Lowest cost; rapid turnaround; high sensitivity [36]. | Highest risk of contamination; slightly lower read accuracy [36]. |

2. How can contamination be minimized in sensitive NGS workflows?

Contamination is a major concern, especially for highly sensitive PCR-based methods [36]. Key strategies include:

- Physical Separation: Establish distinct, dedicated areas for pre- and post-PCR/NGS work. Never bring reagents or equipment from the post-amplification area back to the clean setup area [34].

- Rigorous Controls: Always include negative controls (e.g., no-template) to detect carryover contamination [34] [36].

- Technical Vigilance: Use aerosol-filter pipette tips and wear gloves. Consider UV irradiation of workstations and pipettes to damage residual DNA [34].

In Vitro Assay Contamination Control FAQs

1. My cell cultures are contaminated. How can I identify the source and decontaminate?

Table: Common Cell Culture Contaminants and Identification

| Contaminant Type | Common Characteristics | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Media turbidity; rapid pH change (yellow); black sand-like particles under microscope [37]. | Direct microscopic observation; Gram staining; culture methods [37]. |

| Mycoplasma | Subtle changes; premature yellowing of medium; slowed cell growth; altered cell morphology [37]. | PCR; fluorescence staining (e.g., Hoechst); electron microscopy [37]. |

| Fungi | Visible filamentous structures (hyphae); white spots or yellow precipitates in media [37]. | Direct microscopic observation; culture on antifungal plates [37]. |

Decontamination Strategies:

- Antibiotic/Antimycotic Treatment: Apply high concentrations of appropriate agents (e.g., tetracyclines for mycoplasma; penicillin/streptomycin for bacteria; amphotericin B for fungi) for shock treatment, then maintain with regular doses [37].

- Physical Methods: For severe and persistent contamination, autoclave contaminated cultures and reagents. Mycoplasma can also be heat-inactivated at 41°C for 10 hours [37].

- Source Elimination: If contamination is recurrent, discard all potentially contaminated reagents and cell lines. Re-isolate or obtain new, clean cell stocks [37].

2. What is a structured response plan for a viral contamination event in a bioproduction facility?

A robust response plan is critical for patient safety and resuming operations [38]. A three-phase approach is recommended:

Key Elements:

- Phase 1: Confirmation & Containment: Immediately notify the core Virus Contamination Response Team (VCRT) upon an out-of-specification (OoS) result. Confirm the finding with a third-party specialist and initiate physical containment of affected areas and materials [38].

- Phase 2: Identification & Decontamination: Identify the contaminating virus and determine the full extent of the contamination. Execute a thorough decontamination of the facility using validated methods, and verify success using biological indicators [38].

- Phase 3: Resumption & Prevention: Conduct a thorough root cause investigation. Implement robust Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA) before systematically returning the facility to service [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Viral Diagnostics | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target DNA sequences with minimal error rates, crucial for accurate sequencing and detection [33] [35]. | Essential for reducing sequence errors in PCR products intended for downstream cloning or NGS library prep. |

| Hot-Start Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until a high-temperature activation step [33] [35]. | Critical for improving assay specificity and sensitivity, especially in multiplex PCR. |

| PCR Additives (e.g., GC Enhancer) | Aids in denaturing complex templates with high GC-content or secondary structures, ensuring efficient amplification [33] [34]. | Polymerase-specific formulations are most effective. |

| Nucleic Acid Probes (for Capture) | Enriches for target pathogen sequences from complex samples prior to NGS, increasing sensitivity for known viruses [36]. | Allows for parallel detection of multiple pre-defined pathogens in a single assay. |

| dNTP Mix | Provides the essential nucleotides (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA polymerase to synthesize new DNA strands [33]. | Must be fresh and equimolar to prevent misincorporation errors. Aliquoting is recommended. |

| Mg²⁺ Solution | A critical co-factor for DNA polymerase activity; concentration directly influences enzyme fidelity, specificity, and yield [33] [35]. | Requires optimization for each primer-template system. Vortex thoroughly before use. |

Strategies for Raw Material Sourcing and Cell Bank Characterization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key principles for sourcing raw materials to minimize viral contamination risk? A comprehensive, risk-based control strategy is essential for raw materials (RMs) to ensure the highest attainable safety concerning viruses and other adventitious agents [39]. Key principles include:

- Risk Assessment: Evaluate all RMs entering the process, focusing on their origin (synthetic, plant, animal, or microbiologically derived), nature, and quality oversight [39] [40].

- Supplier Qualification: Purchase RMs from approved suppliers who provide full traceability and data on their manufacturing process, handling, and packaging [40] [41].

- Robust Testing: Implement a testing program for bioburden and specific pathogens, commensurate with the RM's risk level and intended use [39] [40].

FAQ 2: My cell culture shows a sudden drop in pH and appears turbid. What is the likely cause? This is a classic sign of bacterial contamination [42]. Under a microscope, bacteria may appear as tiny, moving granules between your cells [42]. You should isolate the contaminated culture immediately and decontaminate the work area [42].

FAQ 3: What are the critical tests for characterizing a Master Cell Bank (MCB)? Characterization of an MCB confirms identity, genetic stability, and purity [43]. The battery of tests typically includes [43]:

- Identity: Species confirmation via methods like STR analysis or QPCR [43] [44].

- Purity (Sterility): Tests for microbial contaminants (sterility, mycoplasma) and adventitious viruses [43].

- Viral Safety: Specific tests for retroviruses and other viruses relevant to the cell species (e.g., bovine, porcine, or human viruses depending on the cell's history) [43].

FAQ 4: How can I prevent cross-contamination of my cell line with other fast-growing lines? Cross-contamination is a serious and established problem [42]. To prevent it:

- Source Carefully: Obtain cell lines from reputable cell banks [42].

- Authenticate Routinely: Periodically check cell line characteristics using DNA fingerprinting, karyotype, or isotype analysis [44] [42].

- Practice Aseptic Technique: Always maintain good aseptic technique in the lab [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Recurring Microbial Contamination in Media Preparation

Scenario: A firm experiences multiple media fill failures. The contaminant was not recovered using conventional microbiological techniques but was later identified via 16S rRNA gene sequencing as Acholeplasma laidlawii, a mycoplasma species known to penetrate 0.2-micron filters [45].

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

- Identify the Organism: Use specialized methods like PCR or gene sequencing to detect cell wall-deficient organisms like mycoplasma that do not grow on standard media [45] [42].

- Trace the Source: The investigation confirmed the contaminant was present in the non-sterile bulk powder of the tryptic soy broth (TSB) used [45].

- Implement Corrective Actions:

- Change Filtration Protocol: For media preparation, consider using a 0.1-micron filter to retain small microorganisms like Acholeplasma laidlawii [45].

- Source Sterile Materials: Where possible, use sterile, irradiated media powders from commercial suppliers to avoid the risk entirely [45].

- Validate Cleaning Procedures: Revalidate cleaning procedures to verify the removal of the contaminant [45].

Problem: Raw Material with High Contamination Risk

Scenario: A new raw material of animal origin is required for cell culture media. How do you mitigate the inherent viral contamination risk?

Risk Mitigation Protocol:

- Classify the Material: Classify the RM as high-risk due to its animal origin [39] [40].

- Assess Usage Point: Determine if the material is used upstream (higher risk due to potential virus amplification) or downstream [39].

- Select Mitigations:

- Prefer Animal-Component Free (ACF): Source an ACF version of the material if available [39].

- Supplier Qualification: Audit the supplier to ensure they use viral inactivation steps in their production process and provide a comprehensive Certificate of Analysis (C of A) [39] [41].

- Implement Testing: Perform in-house viral testing or specific pathogen testing on the RM lot prior to release for use [39] [40].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Adventitious Virus Detection in Cell Banks

Method: In Vitro Assay for Adventitious Agents [43]

Objective: To detect a wide range of potential viral contaminants in cell bank samples.

Procedure:

- Cell Lines: Inoculate the test sample onto a panel of cell lines with proven susceptibility to various viruses. Common lines include Vero, MRC-5, HeLa, and CHO cells [43].

- Incubation: Maintain the cultures for at least 28 days, with periodic subculturing [43].

- Observation: Monitor the cells daily for cytopathic effects (CPE), such as changes in morphology, cell lysis, or granulation.

- Confirmation: Use hemadsorption or hemagglutination assays at the end of the observation period to detect the presence of non-cytopathic viruses [43].

Protocol 2: Bioburden Testing for Raw Materials

Method: Total Aerobic Microbial Count (TAMC) and Total Yeast and Mould Count (TYMC) [40]

Objective: To enumerate the number of viable microorganisms in a raw material sample.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a 1:10 dilution of the sample (10g or 10mL in a suitable diluent). For solids, use a validated method to extract microorganisms [40].

- Method Suitability (Bacteriostasis/Fungistasis): Challenge the sample with a low-level inoculum (e.g., S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, C. albicans, B. subtilis, A. brasiliensis) to confirm the material itself does not inhibit microbial growth [40].

- Enumeration: Perform one of the following methods, chosen hierarchically [40]:

- a) Membrane Filtration: Filter the sample, place the membrane on Tryptone Soy Agar (TSA) for TAMC and Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) for TYMC.

- b) Pour Plate: Mix the sample with liquefied agar and pour into a Petri dish.

- c) Spread Plate: Spread the sample on the surface of solid agar.

- Incubation and Counting:

- Incubate TAMC plates at 30-35°C for 3-5 days.

- Incubate TYMC plates at 20-25°C for 5-7 days.

- Count all colonies and report as cfu per gram or milliliter [40].

Table 1: Microbial Limit Criteria for Non-Sterile Raw Materials

| Test | Acceptance Criteria (cfu/g or mL) | Pharmacopeia Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Total Aerobic Microbial Count (TAMC) | Not more than 10³ (Maximum acceptable count: 2000) | Ph. Eur. 5.1.4 [40] |

| Total Yeast and Mould Count (TYMC) | Not more than 10² (Maximum acceptable count: 200) | Ph. Eur. 5.1.4 [40] |

Table 2: Essential Characterization Tests for Cell Banks

| Test Category | Specific Assays | Applicability (MCB / WCB / EPCB) |

|---|---|---|

| Identity | STR Analysis, Cytochrome C Oxidase QPCR [43] [44] | MCB, (WCB), EPCB [43] |

| Purity - Sterility | Sterility Test (EP/USP/JP) [43] | MCB, WCB, EPCB [43] |

| Purity - Mycoplasma | Mycoplasma qPCR or Culture Method [43] | MCB, WCB, EPCB [43] |

| Purity - Adventitious Viruses | In Vitro Assay (28 days, 3 cell lines), In Vivo Assay [43] | MCB, (WCB), EPCB [43] |

| Viral Safety | Retrovirus Tests (TEM, XC plaque assay, PERT assay) [43] | MCB, WCB, EPCB [43] |

| Species-Specific Viruses | MAP, HAP, or qPCR for bovine/porcine/human viruses [43] | MCB, (WCB) [43] |

Visual Workflows and Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Supports cell growth and maintenance. | Use sterile, endotoxin-tested media. Be aware that non-sterile powder is a contamination risk [45] [42]. |

| Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) | Used in media fill simulations to test aseptic processes. | Can be a source of cryptic contaminants like Acholeplasma laidlawii; consider sterile, irradiated forms [45]. |

| Antibiotics & Antimycotics | Suppress bacterial and fungal growth. | Should not be used routinely to avoid masking low-level contamination and developing resistance [42]. |

| Sterilizing Grade Filters | Remove microorganisms from solutions and gases. | Standard 0.2-micron filters may not retain mycoplasma; 0.1-micron filters are required for these small organisms [45]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | For cryopreservation and long-term storage of cell banks. | Must be stored in vapor-phase LN2 tanks with alarm-monitored backup supply for security [46]. |

| Characterization Assays | (qPCR, TEM, in vivo/in vitro virus tests) | Used to confirm identity and purity of cell banks and to test for specific adventitious agents [43]. |

Leveraging Alien Controls and Bioinformatic Tools like Cont-ID for Cross-Contamination Monitoring

Welcome to the Cross-Contamination Monitoring Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers implementing advanced cross-contamination monitoring protocols, specifically focusing on the use of Alien Controls and the bioinformatic tool Cont-ID. These materials support viral diagnostic workflows and are framed within a broader thesis on reducing contamination risks in high-throughput sequencing (HTS) for virus detection.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is an "Alien Control" and why is it mandatory for cross-contamination monitoring with HTS?

An Alien Control is defined as a matrix infected by a target (the "alien target") that belongs to the same group as the target organisms to be tested but cannot be present in the actual samples of interest [47]. It is processed alongside your samples as an external control.

- Function: It acts as a sentinel to monitor cross-contamination within a sequencing batch. The presence of reads from the alien virus in any test sample is a definitive indicator of contamination from the alien control to that sample [47].

- Why it's mandatory: HTS technologies have极高的分析灵敏度, where even a single viral read can be detected. The alien control provides an empirical, batch-specific measure of the contamination level, moving beyond arbitrary thresholds and enabling reliable bioinformatic filtering [47].

Q2: Our lab is new to Cont-ID. What are the basic requirements to run it?

To use Cont-ID effectively, you need to meet the following prerequisites [47]:

- Sequencing Technology: Cont-ID is designed for data generated by Illumina sequencing technology.

- Batch Processing: All samples in the sequencing batch must have been processed in parallel in the laboratory, following the same steps.

- Alien Control: At least one alien control must be included in the batch.

- Bioinformatic Input: Cont-ID relies on the output of standard bioinformatic analyses. You must provide a file containing the read counts for each virus species identified in every sample of the batch.

Q3: We detected a low number of viral reads in a sample. How can we determine if it's a true infection or cross-contamination?

This is a core challenge that the Alien Control/Cont-ID system is designed to address. The following workflow outlines the diagnostic process:

Q4: What are the most common sources of cross-contamination in HTS workflows, and how can we mitigate them?

Cross-contamination can occur at multiple stages. The table below summarizes common sources and preventive measures.

| Stage | Contamination Risk | Preventive Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Aerosols or carryover between samples in a plate [47]. | Use of uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) to degrade carryover amplicons, physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas [47]. |

| Library Preparation | Splashing, pipetting errors, or reagent contamination [47]. | Use of alternate dual indexes to identify index hopping, inter-run washing steps, and laboratory decontamination of surfaces and equipment [47]. |

| Sequencing | Index hopping or carryover from a previous sequencing run on the same machine [47]. | Use of unique dual indexes (UDIs), and following manufacturer decontamination protocols for the sequencer [47]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Cont-ID is not classifying any detections, or the classification accuracy seems low.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect input file format | Ensure your read count file matches the expected format specified in the Cont-ID documentation. Validate the file with a simple test dataset. |

| Alien control not properly specified | Verify that the alien control is correctly labeled in your sample sheet and that the alien virus is abundant enough in the control to be detected. |

| Low-level contamination is below the detection threshold | Cont-ID's accuracy (91%) relies on a clear contamination signal. For very low-level cross-over, manual inspection and confirmation may still be necessary [47]. |

Problem: We are seeing a high rate of cross-contamination across many samples, as indicated by the alien control.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Contaminated shared reagents | Prepare fresh aliquots of critical reagents like water and buffers. Use filter tips for all pipetting steps. |

| Inadequate cleaning of equipment | Implement more rigorous decontamination protocols for laboratory equipment, such as robotic workstations and pipettes. Increase the frequency of cleaning. |

| Aerosol generation during sample handling | Review and refine techniques to minimize aerosol generation. Centrifuge tubes briefly before opening, and avoid vigorous vortexing of open tubes. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Alien Controls in a Viral Metagenomics Study

- Alien Selection: Choose an alien virus that is phylogenetically similar to the viruses you are detecting but is impossible to find in your sample type (e.g., a plant virus in human clinical samples) [47].

- Sample Preparation: Grow the alien virus in its appropriate host system. Quantify the virus to achieve a high concentration, ideally close to the highest expected concentration in your test samples [47].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Process the alien control sample through the same nucleic acid extraction protocol as your test samples.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Include the alien control in the same library preparation batch and sequencing run as all your test samples.

- Data Analysis: Use the alien control's data as a reference point in your bioinformatic pipeline (e.g., Cont-ID) to assess cross-contamination levels.

Protocol: Validating Cont-ID Performance in Your Lab

To validate Cont-ID, you can create a mock sequencing batch with known positive and negative samples.

- Materials Needed:

- Known positive samples for specific viruses.

- Known negative samples.

- Your chosen alien control.

- Procedure:

- Spike known positive samples at various concentrations (high, medium, low).

- Process the entire mock batch (positives, negatives, alien control) together through extraction, library prep, and sequencing.

- Run the generated HTS data through your standard viral detection pipeline to get read counts.

- Execute Cont-ID using the read count file and the alien control designation.

- Compare Cont-ID's classifications against the expected results to calculate its accuracy and sensitivity in your specific lab context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details essential materials for implementing this contamination monitoring framework.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Alien Virus Isolate | The core of the control system. Provides a measurable signal for tracking the transfer of genetic material between samples during processing [47]. |

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | DNA barcodes used during library preparation. UDIs minimize the misassignment of reads to the wrong sample (index hopping), a common source of contamination in HTS [47]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A critical reagent for preparing solutions and dilutions. Using certified nuclease-free water prevents the introduction of external nucleic acids that can contaminate experiments. |

| Cont-ID Software | The bioinformatic tool that automates the detection of cross-contamination by analyzing read count patterns and the alien control signal across a batch of samples [47]. |

Environmental Monitoring and Rapid Mobile qPCR for Surface Contamination

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to support researchers in reducing contamination risks in viral diagnostic and environmental monitoring workflows utilizing rapid mobile qPCR.

Troubleshooting Guide for Contamination and Assay Performance

The following table outlines common qPCR issues encountered during environmental monitoring, their potential causes, and recommended corrective actions.

| Issue Observed | Potential Causes | Troubleshooting Steps & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification in No Template Control (NTC) [3] [48] [49] | Contaminated reagents (primers, master mix, water) [48]; Carryover amplicon contamination from previous runs [3]; Aerosol contamination during pipetting [3]. | Replace reagents systematically [3]; Implement physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas [3]; Use aerosol-resistant filter tips [3]; Decontaminate surfaces with 10-15% fresh bleach solution [3]; Employ UNG (uracil-N-glycosylase) enzyme treatment to degrade carryover contaminants [3] [48]. |

| High Ct (Cycle Threshold) Values/Late Amplification [50] | Low template concentration/quality [50]; Presence of PCR inhibitors [50] [49]; Degraded primers/probes [50]; Suboptimal reaction efficiency [50]. | Confirm template quality and concentration [50]; Check primer/probe integrity and freeze-thaw cycles [50]; Use additives like BSA or DMSO to counteract inhibitors [49]; Verify pipetting accuracy and reagent mixing [50]. |

| Non-Specific Amplification (e.g., Multiple Peaks in Melt Curve) [50] | Primers binding to non-target sequences; Annealing temperature too low [50]; Contaminated reagents or environment [50]. | Optimize annealing temperature [50]; Check primer design for specificity; Review assay conditions for contamination [50]. |

| No Amplification [50] [49] | Template omission [49]; Presence of strong PCR inhibitors [49]; Incorrect thermal cycler settings [50]; Failed reagent (e.g., degraded probe, enzyme inactivity) [49]. | Verify template was added [49]; Check thermal cycler program [50]; Include a positive control to confirm reagent/assay functionality [50]; Use an internal positive control (IPC) to check for inhibition [49]. |

| Inconsistent Replicates [50] | Inconsistent pipetting [50]; Inadequate mixing of reagents [50]; Uneven sealing of reaction plates causing evaporation [50]. | Calibrate pipettes and ensure proper technique [50]; Mix reagents thoroughly before aliquoting [50]; Ensure plates are properly sealed [50]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical control for monitoring contamination in every qPCR run? The No Template Control (NTC) is essential. It contains all reaction components except the nucleic acid template. Amplification in the NTC indicates contamination of one or more reagents or the environment with the target sequence, necessitating a review of procedures and reagents [3] [48].

Q2: How can laboratory layout minimize contamination risks? Implementing a unidirectional workflow with physically separated areas is fundamental [3] [51].

- Pre-PCR Area (Pre-amplification): Dedicated to reagent preparation, sample handling, and reaction setup. This area should have dedicated equipment, lab coats, and consumables [3].

- Post-PCR Area (Post-amplification): Dedicated to the qPCR instrument and analysis of amplified products. Nothing from the post-PCR area should return to the pre-PCR area without rigorous decontamination [3] [51].

Q3: Our research involves mobile qPCR for onsite water testing. How reliable are the results from portable systems? Validation studies demonstrate that onsite qPCR with portable equipment can yield highly reliable results. One study showed that marker genes quantified with a portable Q qPCR instrument agreed within ±0.3 log10 units with results from conventional laboratory equipment, supporting its use for rapid, onsite decision-making [52].

Q4: Besides laboratory surfaces, what unexpected items can be sources of contamination? Personal items such as mobile phones, jewelry, and even hair can transmit contamination. One study found virus RNA on 38.5% of healthcare workers' mobile phones [53]. Adherence to strict personal protective equipment (PPE) protocols and avoiding introducing personal items into pre-PCR areas is critical [3] [53].

Experimental Protocol: Onsite qPCR for Fecal Pollution Tracking in Surface Waters

This detailed methodology, adapted from a field deployment study, enables rapid, onsite quantification of microbial source-tracking markers in water samples using portable equipment [52].

Principle

This protocol uses a portable qPCR system to quantitatively detect host-associated genetic markers (e.g., HF183 for human-specific Bacteroides) directly at the sampling site. This allows for near real-time assessment of fecal contamination in surface waters, reducing the risk of sample alteration during transport and storage [52].

Equipment & Reagents

- Portable Q qPCR Instrument (e.g., Quantabio) [52]

- Portable vacuum pump and filtration units [52]

- Portable centrifuge and vortex mixer [52]

- Portable fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) for DNA quantification [52]

- DNeasy PowerWater Kit (Qiagen) or equivalent for DNA extraction [52]

- qPCR master mix and validated primer/probe sets for target genes (e.g., HF183, 16S rRNA, E. coli rodA) [52]

- Aerosol-resistant filtered pipette tips [3]

- Personal protective equipment (dedicated lab coats, gloves) [3]

- Surface decontamination supplies (fresh 10% bleach, 70% ethanol) [3]

Step-by-Step Procedure

Workflow for Onsite qPCR Analysis

- Onsite Sample Collection: Collect water samples (e.g., 100-300 mL from river, storm drain) in sterile bottles. Simultaneously measure physicochemical parameters (temperature, pH, turbidity) using portable meters [52].

- Sample Concentration: Filter the water sample through a 0.22 µm membrane filter using a portable vacuum pump to concentrate microbial biomass [52].

- Onsite DNA Extraction:

- Transfer the filter membrane to the lysis tubes provided in the DNA extraction kit.

- Perform the extraction protocol (including bead-beating via vortex) strictly within the designated "pre-PCR" area of the mobile laboratory, using dedicated portable equipment (centrifuge, vortex) [52].

- Elute the purified DNA in the provided elution buffer.

- DNA Quality Control: Use a portable fluorometer to quantify the extracted DNA yield. This step is optional but helps assess extraction success [52].

- qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare the qPCR master mix on a clean, decontaminated surface in the pre-PCR area.

- Include essential controls: No Template Control (NTC), positive control (with known template), and if applicable, a negative control for extraction [48].

- Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips throughout.

- Aliquot the master mix and add the extracted DNA sample.