Troubleshooting Viral Metagenomic Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Clinical Validation

This article provides a systematic framework for troubleshooting viral metagenomic sequencing, addressing critical challenges from sample preparation to data validation.

Troubleshooting Viral Metagenomic Sequencing: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for troubleshooting viral metagenomic sequencing, addressing critical challenges from sample preparation to data validation. It covers foundational principles of virome analysis, compares established methodological approaches like VLP enrichment and bulk metagenomics, and offers evidence-based optimization strategies for amplification bias, host depletion, and library preparation. Drawing on recent studies, the guide also outlines rigorous validation techniques using mock communities and cross-method comparisons, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to enhance sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility in detecting viral pathogens across diverse clinical samples.

Understanding Viral Metagenomics: Core Concepts and Technical Hurdles

FAQs: Core Concepts and Definitions

Q1: What is the precise definition of a "virome"? The virome refers to the entire assemblage of viruses found in a specific ecosystem, organism, or holobiont. It includes all viral nucleic acids investigated through metagenomic sequencing and encompasses viruses infecting eukaryotic cells, bacteriophages, and other viral elements found in the environment [1].

Q2: How do Virus-Like Particles (VLPs) differ from infectious viruses? VLPs are molecules that closely resemble viruses in structure but are non-infectious because they lack viral genetic material. They are formed through the self-assembly of viral structural proteins and cannot replicate within host cells [2].

Q3: What is the role of the human virome in health? The human virome is a component of the human microbiome. Its impact on health extends beyond the traditional view of viruses as pathogens. It can influence host physiology, immunity, and disease susceptibility, acting in ways that can be commensal, mutualistic, or pathogenic [3].

Q4: Why is viral metagenomics particularly challenging compared to bacterial microbiome studies? Unlike bacteria, viruses lack a universal marker gene (like bacterial 16S rRNA). This, combined with their immense genetic diversity, small genome size, and low abundance in many samples, makes their detection and classification difficult without targeted metagenomic approaches [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My viral metagenomic samples have low sensitivity and high host background. What steps can I take? This is a common issue, especially with low-biomass clinical samples. The following workflow is critical for success [4]:

- Enrich Virions: Filter samples through a 0.45 µm membrane to remove prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, followed by precipitation using PEG/NaCl.

- Remove Extracellular Nucleic Acids: Treat viral concentrates with DNase I and RNase to degrade free nucleic acids that are not protected within a viral capsid. Deactivate enzymes by heating before proceeding [4].

- Consider Targeted Enrichment: For known viruses, using a targeted panel (e.g., Twist Bioscience Comprehensive Viral Research Panel) can increase sensitivity by 10–100 fold compared to untargeted sequencing [5].

Q2: I am detecting consistent background microbial reads in my negative controls. What is the source? This is likely reagent contamination (often called the "kitome"). Contaminating nucleic acids are common in extraction kits, polymerases, and water [6].

- Solution: Always include negative control samples (e.g., sterile water) processed identically to your experimental samples. This allows you to identify and bioinformatically subtract background contaminants. Where possible, use the same batches of all reagents for a project to maintain consistency [6].

Q3: Should I choose Illumina or Nanopore sequencing for my viral metagenomics project? The choice depends on your goals for sensitivity, speed, and cost [5].

- Untargeted Illumina Sequencing: Offers good sensitivity at lower viral loads and is optimal for host gene expression analysis.

- Untargeted Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Sequencing: Provides rapid, real-time data acquisition and better specificity than Illumina but may require longer, more costly runs to achieve comparable sensitivity at low viral loads.

- Targeted/Enrichment Approaches (e.g., Illumina-based): Best for detecting low viral loads of known viruses but may miss novel or untargeted organisms.

The table below summarizes a comparative evaluation of these approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Metagenomic Sequencing Approaches for Viral Detection

| Method | Best Use Case | Sensitivity | Turnaround Time | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted Illumina | Comprehensive pathogen detection; host transcriptomics | Good at lower viral loads | Longer | High sensitivity; ideal for combined host-pathogen analysis |

| Untargeted ONT | Rapid detection of high viral loads; field sequencing | Good at high viral loads | Short | Real-time analysis; long reads can help with assembly |

| Targeted Enrichment | Sensitive detection of a pre-defined set of viruses | Excellent (10-100x over untargeted) | Varies | Maximizes sensitivity for known pathogens |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Purification of Virus-Like Particles from Sewage or Environmental Water

This protocol is adapted from established methods for virion enrichment [4].

- Sample Preparation: Add 25 mL of glycine buffer (0.05 M glycine, 3% beef extract, pH 9.6) to 200 mL of sample. Mix to detach viral particles from organic material.

- Clarification: Centrifuge at 8,000 × g for 30 minutes. Collect the supernatant.

- Filtration: Filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm polyethersulfone (PES) membrane to remove prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

- Precipitation: Precipitate viruses from the filtrate by adding PEG 8000 (80 g/L) and NaCl (17.5 g/L). Agitate at 100 rpm overnight at 4°C.

- Pellet Virions: Centrifuge for 90 minutes at 13,000 × g. Resuspend the resulting virus-containing pellet in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and store at -80°C.

Protocol 2: Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction from Purified VLPs

This is a critical step to obtain pure viral genetic material for sequencing [4].

- Nuclease Treatment: Treat the purified VLP suspension with DNase I and RNase at 37°C for 15 minutes to remove any contaminating nucleic acids external to the capsids.

- Enzyme Inactivation: Heat the sample to 70°C for 5 minutes to deactivate the nucleases.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract viral nucleic acids using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit, Macherey-Nagel NucleoSpin RNA Virus). For samples with very low nucleic acid yield, a whole genome amplification step may be necessary.

- Quantification: Quantify the extracted DNA/RNA using sensitive fluorescence-based methods (e.g., RiboGreen or PicoGreen assays).

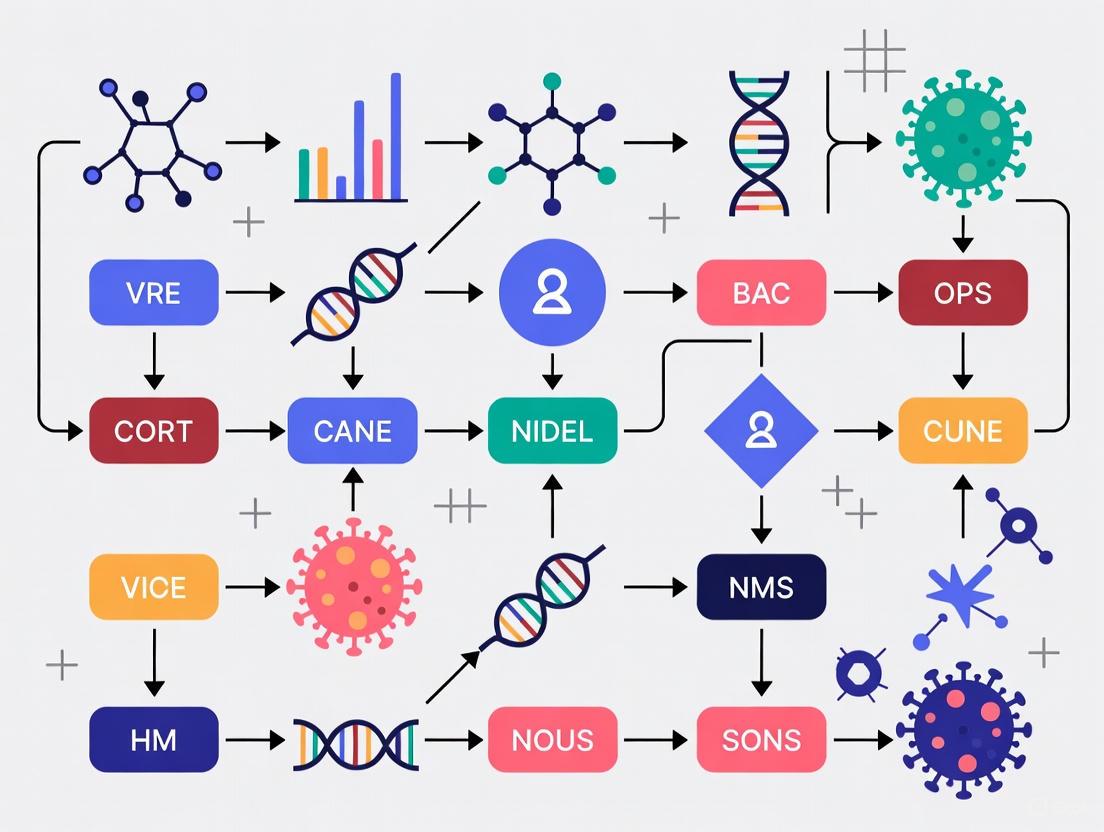

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for a viral metagenomics study, from sample to data:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Viral Metagenomics Workflows

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I & RNase | Degrades free nucleic acid not protected within viral capsids; critical for reducing host background. | Must be used prior to nucleic acid extraction; requires a heat inactivation step [4]. |

| PEG 8000 | Precipitates and concentrates virus-like particles from large volume liquid samples. | Used with NaCl for overnight precipitation [4]. |

| 0.45 µm PES Filter | Removes bacterial and eukaryotic cells from the sample, enriching for smaller virions. | A key step in physical purification [4]. |

| Whole Genome Amplification Kit | Amplifies minute amounts of viral DNA/cDNA to levels sufficient for library preparation. | Essential for low-biomass samples [4]. |

| Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isletes DNA and/or RNA from purified VLPs. | Kits from Qiagen, Macherey-Nagel, and others are commonly used [4]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA from total RNA samples, enriching for viral and host mRNA. | Improves sequencing depth of targets [5]. |

| Targeted Enrichment Panels | Biotinylated oligonucleotide panels to selectively capture and enrich nucleic acids from known viruses. | The Twist Comprehensive Viral Research Panel targets 3,153 viruses for increased sensitivity [5]. |

Advanced Concepts: From Contamination to Complex Communities

Understanding and Mitigating Contamination Contamination is a major confounder in viral metagenomics. Sources can be external (reagents, kits, laboratory environment) or internal (cross-over from other samples) [6]. The diagram below maps the types and sources of contamination to guide your troubleshooting strategy.

The Ecological Impact of the Virome Beyond technical troubleshooting, it's crucial to understand the biological context. The virome is not a passive entity; it plays an active role in shaping microbial ecosystems. A 2025 study analyzing global ocean data found that including viruses in co-occurrence network analyses significantly increased the complexity and stability of prokaryotic microbial communities. This demonstrates that viruses are integral to maintaining the integrity and resilience of ecological networks [7].

FAQs on Low Viral Biomass

FAQ 1: What are the major sources of contamination in low viral biomass samples? In low-biomass viral studies, contaminants can be introduced at virtually every stage. The major sources are categorized as external contamination, which includes:

- Laboratory Reagents and Kits: Extraction kits, polymerases, and even molecular-grade water can contain microbial DNA, often referred to as "kitome" [6] [8]. The composition of these contaminants can vary between different lots of the same kit [6] [8].

- Laboratory Environment and Personnel: Contaminating nucleic acids can originate from skin, laboratory surfaces, air, and equipment [6] [9] [8].

- Sample Collection Materials: Collection tubes and swabs can be a source of contamination if not properly decontaminated or certified DNA-free [6] [9].

FAQ 2: How can I minimize contamination during sample collection and processing? Adopting a contamination-informed workflow is critical [9]. Key strategies include:

- Decontaminate Thoroughly: Use single-use, DNA-free collection vessels where possible. Decontaminate reusable equipment with 80% ethanol followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution (e.g., bleach, UV-C light) to remove both viable cells and trace DNA [9].

- Use Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear gloves, masks, and clean suits to limit the introduction of contaminants from personnel [9].

- Include Comprehensive Controls: Process negative controls (e.g., empty collection vessels, aliquots of preservation solution, swabs of the air) alongside your samples from collection through sequencing to identify the contaminant background [9].

FAQ 3: My sequencing yield is very low. What are the common causes? Low library yield is a frequent issue with low-biomass samples. The primary causes and their solutions are summarized in the table below [10].

Table 1: Common Causes and Corrective Actions for Low Library Yield

| Cause | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality / Contaminants | Enzyme inhibition by residual salts, phenol, or EDTA. | Re-purify input sample; ensure high purity (260/230 > 1.8); use fresh wash buffers [10]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Overestimating usable material with UV absorbance (e.g., NanoDrop). | Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit, PicoGreen) for template quantification [10]. |

| Fragmentation Inefficiency | Over- or under-fragmentation reduces adapter ligation. | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragmentation profile before proceeding [10]. |

| Suboptimal Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert ratio. | Titrate adapter:insert molar ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; maintain optimal temperature [10]. |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired fragments are excluded during size selection, leading to sample loss. | Optimize bead-to-sample ratios to ensure recovery of the target fragment range [10]. |

FAQs on High Host Background

FAQ 1: What methods can I use to deplete host nucleic acids? While the search results do not specify individual commercial kits, they emphasize that the need for host genomic background depletion is a key challenge in viral metagenomics [6] [8]. The choice of method (e.g., enzymatic digestion, probe-based capture) depends on your sample type and the required sensitivity for viral detection.

FAQ 2: Why is RNA sequencing more susceptible to contamination than DNA sequencing? RNA sequencing involves an additional reverse transcription (RT) step. It has been found that commercially available RT enzymes can themselves contain viral contaminants, such as equine infectious anemia virus or murine leukemia virus, thereby increasing the background noise [6] [8].

Troubleshooting Common Sequencing Preparation Failures

The following table outlines frequent problems encountered during library preparation, their failure signals, and proven fixes [10].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Sequencing Preparation

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality | Low starting yield; smear in electropherogram; low complexity [10]. | Degraded DNA/RNA; sample contaminants; inaccurate quantification [10]. | Re-purify input; use fluorometric quantification; check 260/280 and 260/230 ratios [10]. |

| Fragmentation / Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; inefficient ligation; adapter-dimer peaks [10]. | Over/under-shearing; improper buffer conditions; suboptimal adapter-to-insert ratio [10]. | Titrate fragmentation; verify enzyme activity; optimize adapter concentrations [10]. |

| Amplification / PCR | Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate; bias [10]. | Too many PCR cycles; carryover enzyme inhibitors; primer exhaustion [10]. | Reduce PCR cycles; use master mixes; ensure optimal primer annealing conditions [10]. |

| Purification / Cleanup | Incomplete removal of adapter dimers; high sample loss; salt carryover [10]. | Wrong bead ratio; over-dried beads; inadequate washing; pipetting errors [10]. | Precisely follow cleanup protocols; avoid over-drying beads; use calibrated pipettes [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Contamination-Aware Workflow for Low-Biomass Viral Metagenomics

This protocol integrates best practices for minimizing contamination from sample to sequence [6] [9] [8].

1. Sample Collection

- Materials: Single-use, DNA-free swabs and collection tubes. PPE (gloves, mask, hair net).

- Procedure:

- Decontaminate the sampling site and any non-disposable equipment with 80% ethanol and a DNA-degrading solution.

- Collect the sample using sterile technique, minimizing exposure to the environment.

- Immediately place the sample in a sterile, pre-labeled tube.

- In parallel, prepare field and equipment blanks (e.g., open a sterile tube in the sampling environment, swab a cleaned surface) as negative controls.

2. Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Materials: DNA/RNA extraction kit (use the same lot for all samples in a project), nuclease-free water.

- Procedure:

- Include an extraction blank control (a tube with no sample) processed identically to the experimental samples.

- If possible, use automated extraction systems to reduce the number of manual transfer steps and the associated contamination risk [6] [8].

- Elute the nucleic acids in a suitable nuclease-free buffer.

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Materials: Library prep kit, DNA polymerase, adapter indices.

- Procedure:

- Include the negative controls (field blanks, extraction blanks) in all downstream steps.

- Use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors and variability [10].

- Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for accurate quantification of amplifiable molecules prior to library prep [10].

- Avoid over-amplifying during the PCR enrichment step to prevent artifacts and bias [10].

Workflow for Low-Biomass Viral Metagenomics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | To isolate nucleic acids from samples. | A major source of "kitome" contamination; use the same batch for an entire project to maintain consistency [6] [9] [8]. |

| Fluorometric Quantification Kits (Qubit) | To accurately measure concentration of amplifiable nucleic acids. | More accurate for low-concentration samples than UV absorbance, which can overestimate yield [10]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A solvent for molecular biology reactions. | Can be a source of contaminating DNA; should be certified nuclease-free [6] [8]. |

| Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | To act as a barrier between the operator and the sample. | Reduces contamination from human skin, aerosol droplets, and clothing [9]. |

| DNA Degrading Solutions (e.g., Bleach) | To decontaminate surfaces and equipment. | Critical for removing trace DNA that survives ethanol decontamination or autoclaving [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My metagenomic sequencing pipeline failed with a 'signal 9 (KILL)' error during the alignment step. What is the cause and solution? This error typically indicates that the operating system terminated the process because it exhausted the available memory (RAM) on your server [11]. This is common when aligning to large reference genomes or working with substantial datasets.

- Solution: Reduce the memory footprint of your alignment job. You can:

- Split your reference: Divide your large reference file into smaller segments (e.g., by chromosome), align to each segment separately, and then merge the resulting BAM files [11].

- Reduce the number of threads: Using fewer threads (

-pparameter in Bowtie2) can lower memory consumption. - Check available resources: Use commands like

free -mto monitor your server's memory and swap usage in real-time [12].

FAQ 2: The samtools sort command generates many small temporary BAM files but no final sorted output. What went wrong?

This usually happens when the sorting process runs out of memory before it can complete and merge all temporary files [12]. The process is killed, leaving the intermediate files behind.

- Solution: Use the

-mparameter withsamtools sortto specify the maximum memory per thread. For example,samtools sort -@ 10 -m 4G input.bam -o sorted_output.bamallocates 4 GB of RAM per thread. Ensure the total memory (threads × memory per thread) does not exceed your system's available resources [12].

FAQ 3: How can I manage computational resource errors in a workflow manager like Nextflow? Nextflow provides powerful error-handling strategies to manage transient resource failures.

- Solution: In your Nextflow process definition, use the

errorStrategyandmaxRetriesdirectives. You can configure the workflow to automatically retry a failed task with increased resources. For example [13]: This script will retry a process (up to 3 times) if it fails with exit code 140 (often an out-of-memory error), each time doubling the memory and time allocated [13].

FAQ 4: What is a key advantage of long-read sequencing technologies like Oxford Nanopore (ONT) for viral metagenomics? A primary advantage is the ability to perform real-time, unbiased pathogen detection without the need for predefined targets, which is crucial for identifying novel or unexpected viral strains [14]. ONT sequencing also facilitates the assembly of complete viral genomes, enabling direct phylogenetic analysis for outbreak surveillance [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Common Computational Resource Exhaustion

Problem: Tools in your pipeline (e.g., aligners, sorters) are killed or fail without producing output.

| Symptom | Root Cause | Debugging Command | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

bowtie2-align died with signal 9 (KILL) [11] |

Out of Memory (OOM) | free -m |

Split reference file; reduce number of threads (-p) [11]. |

samtools sort produces many temp files but no output [12] |

Insufficient memory for final merge | ls -la sorted.bam* |

Use -m flag to limit memory per thread (e.g., -m 4G) [12]. |

| Workflow task fails intermittently | Transient resource contention | Check .command.log in work directory [13] |

Implement a retry with increased memory in Nextflow config [13]. |

Guide 2: Optimizing Wet-Lab Protocols for Different Sample Types

Problem: Low viral read count or high host contamination in sequencing data from specific specimens.

| Step | Respiratory Specimens | Blood Specimens | Fecal Specimens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Pre-processing | Filter through 0.22 µm filter to remove host cells and debris [14]. | Centrifugation to collect serum or plasma [15]. | Resuspend in PBS, vortex, and freeze-thaw cycles [15]. |

| Host DNA/RNA Depletion | Treat filtered sample with DNase to degrade residual host DNA [14]. | Filter through 0.45 µm filter; treat with DNase/RNase enzyme mix [15]. | Requires vigorous DNase/RNase treatment (e.g., 90 mins) due to complex matrix [15]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Separate viral DNA and RNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA & Viral RNA Mini Kits) with LPA carrier [14]. | Use viral RNA extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit) [15]. | Use specialized stool DNA/RNA kits to inhibit PCR inhibitors. |

| Amplification | Sequence-independent, single-primer amplification (SISPA) is effective for unbiased amplification [14]. | Random hexamer-based reverse transcription and second-strand synthesis [15]. | SISPA or other whole genome amplification methods suitable for complex samples. |

Experimental Protocols for Viral Metagenomics

Protocol 1: Comprehensive ONT Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

This protocol is adapted from a large-scale clinical study for unbiased virus detection [14].

Sample Preparation:

- Resuspend clinical samples (e.g., respiratory, feces) in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) to a final volume of 500 µL.

- Centrifuge through a 0.22 µm filter to remove eukaryotic cells and bacterial-sized particles.

- Treat the filtered sample with TURBO DNase (2 U/µL) at 37°C for 30 minutes to degrade unprotected host nucleic acids.

Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Split the DNase-treated sample for separate DNA and RNA extraction.

- For DNA: Use the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit. Add linear polyacrylamide (50 µg/mL) to the lysis buffer at 1% (v/v) to enhance precipitation.

- For RNA: Use the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit with the same LPA enhancement. Perform an additional on-column DNase treatment.

Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer Amplification (SISPA):

- For RNA: Perform reverse transcription with SISPA primer A (5’-GTTTCCCACTGGAGGATA-(N9)-3’) using SuperScript IV. Follow with second-strand synthesis using Sequenase DNA Polymerase and RNase H treatment.

- For DNA: Denature DNA and anneal with SISPA primer A, then perform DNA extension with Sequenase.

- Amplify both cDNA and DNA products via PCR using Primer B (tag-only sequence).

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Barcode the amplicons using an ONT rapid barcoding kit.

- Pool the barcoded libraries and load them onto a MinION flow cell for sequencing.

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis of Specimen Performance

This protocol outlines the methodology for a prospective study comparing diagnostic yields across different sample types, as used in tuberculosis research [16]. The same principles apply to viral metagenomics.

Patient Cohort and Sample Collection:

- Enroll patients with presumptive infection (e.g., pulmonary symptoms).

- Collect matched respiratory tract specimens (RTS: sputum/BALF) and alternative specimens (e.g., blood, stool) concurrently.

Parallel Processing:

- Process all sample types (RTS, blood, stool) using identical, standardized methods for nucleic acid extraction.

- Apply the same downstream detection assay (e.g., multiplex PCR, targeted RT-qPCR, or mNGS) to all specimens.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate and compare sensitivity, specificity, and positive/negative predictive values for each specimen type using RTS results or clinical diagnosis as the reference standard.

- Statistically analyze detection rates in confirmed versus probable cases to determine the utility of alternative specimens in paucibacillary scenarios.

Viral Metagenomic Sequencing Workflow

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Diagnostic Sensitivity Across Specimen Types

Data from clinical studies demonstrates the variable performance of molecular assays depending on the sample matrix. This highlights the importance of specimen selection.

| Specimen Type | Pathogen / Disease | Assay | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Tract (Sputum) [16] | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Xpert MTB/RIF | 66.1% | 100% | Gold standard for pulmonary TB diagnosis. |

| Stool [16] | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Xpert MTB/RIF | 45.3% | 100% | Useful for patients who cannot expectorate sputum. |

| Respiratory [14] | Mixed Viral Infections | ONT mNGS | ~80% concordance | N/R | Achieved 80% concordance with clinical diagnostics. |

| Blood [15] | Diverse Virome | Illumina mNGS | N/R | N/R | Dominated by Anelloviridae and Parvoviridae. |

Abbreviation: N/R = Not Reported in the cited study.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Metagenomics

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit & QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit [14] | Parallel extraction of viral DNA and RNA from processed samples. | Adding linear polyacrylamide (LPA) enhances nucleic acid precipitation efficiency [14]. |

| TURBO DNase [14] [15] | Degrades residual host and environmental nucleic acids post-filtration. | Critical step to reduce host background; incubation time may vary by sample type (1 hour for respiratory/blood, 90 mins for stool) [14] [15]. |

| SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase [14] | Generates first-strand cDNA from viral RNA with high efficiency and fidelity. | Used with tagged random nonamers in SISPA for unbiased amplification [14]. |

| ONT Rapid Barcoding Kit [14] | Enables multiplexed sequencing of up to 96 samples on a single flow cell. | Significantly reduces per-sample sequencing cost, making large-scale studies affordable [14]. |

| Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer Amplification (SISPA) [14] | Unbiased amplification of viral nucleic acids without predefined targets. | Primers (e.g., Primer A: 5’-GTTTCCCACTGGAGGATA-(N9)-3’) are key for detecting novel viruses [14]. |

Core Workflow Components and Their Challenges

The foundational steps of viral metagenomic sequencing—extraction, amplification, and enrichment—are critical for success. The table below outlines the purpose and common challenges for each component.

| Workflow Component | Primary Purpose | Key Challenges | Potential Impact on Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction [17] [14] | Isolate pure DNA or RNA from various biological samples (e.g., blood, tissue, sputum). [17] | Sample degradation; limited starting material; contamination from host cells or other sources. [17] [14] | Compromised quality/quantity of extracted nucleic acids can cause sequencing failure or biased data. [17] |

| Amplification [17] [18] | Increase the amount of nucleic acids to obtain sufficient material for sequencing, especially from small samples. [17] | Introduction of PCR amplification bias; generation of PCR duplicates and chimeric fragments. [17] | Uneven sequencing coverage; errors in assembly and variant calling; inaccurate representation of the viral population. [17] |

| Enrichment [17] [18] | Focus sequencing on specific targets (e.g., viral genomes), making the process more cost-effective and sensitive. | Inefficient adapter ligation; uneven capture of target regions. [17] | Decreased on-target data; increased background noise; reduced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance viruses. [17] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: How can I minimize bias during the amplification step?

- Problem: Amplification, particularly PCR, can skew the representation of different sequences in your sample, leading to inaccurate results. [17]

- Solutions: [17]

- Use high-fidelity PCR enzymes specifically designed to minimize amplification bias.

- Optimize your library preparation protocol to maximize library complexity, reducing the reliance on excessive amplification cycles.

- Utilize bioinformatics tools (e.g., Picard MarkDuplicates or SAMTools) in downstream analysis to identify and remove PCR duplicates.

FAQ: What are the best practices to prevent sample contamination?

- Problem: Contamination between samples, especially during pre-amplification steps, can lead to false-positive results. [17]

- Solutions: [17]

- Reduce human contact with samples by implementing automation where possible.

- Dedicate a separate, controlled room or area for pre-PCR setup, physically separating it from post-PCR analysis areas.

- Use filter tips and clean lab equipment meticulously.

FAQ: My library preparation is inefficient, leading to low sequencing output. What could be wrong?

- Problem: A low percentage of fragments have the correct adapters, which decreases data yield and can increase chimeras. [17]

- Solutions: [17]

- Ensure efficient A-tailing of PCR products, a universal procedure that can prevent chimera formation.

- Validate your library construction kit and ensure the enzymatic reactions (end repair, A-tailing, ligation) are performed correctly.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Viral Metagenomic Sequencing with SISPA

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, is designed for unbiased viral detection from clinical specimens using Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer Amplification (SISPA). [14]

1. Sample Pre-processing and Nucleic Acid Extraction [14] * Resuspend the clinical sample (e.g., sputum, feces) in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) to a final volume of 500 µL. * Filter the solution through a 0.22 µm centrifuge tube filter to remove host cells and debris. * Treat the filtered sample with TURBO DNase (5 µL in a 500 µL reaction) at 37°C for 30 minutes to degrade residual host genomic DNA. * Perform separate viral DNA and RNA extractions from the processed sample using commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit and QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit). Add linear polyacrylamide to enhance nucleic acid precipitation.

2. Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer Amplification (SISPA) [14] * For RNA samples: * Mix purified RNA with SISPA primer A (5’-GTTTCCCACTGGAGGATA-(N9)-3’). * Perform reverse transcription using the SuperScript IV First-Strand cDNA Synthesis System. * Conduct second-strand cDNA synthesis using Sequenase Version 2.0 DNA Polymerase. * Treat with RNaseH to remove RNA. * For DNA samples: * Mix extracted DNA with SISPA primer A. * Denature and anneal the primer. * Perform DNA extension using Sequenase Version 2.0 DNA Polymerase. * Amplification: The resulting double-stranded cDNA/DNA is amplified via PCR using a primer that binds to the tag sequence of primer A.

3. Library Preparation and Sequencing [14] * The SISPA amplicons are barcoded using a transposase-based rapid barcoding kit (e.g., from Oxford Nanopore Technologies). * Barcoded libraries are pooled and sequenced on a long-read platform (e.g., Nanopore MinION).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| TURBO DNase [14] | Degrades residual host genomic DNA after sample filtration, reducing background and improving detection of viral pathogens. |

| SISPA Primer A [14] | A tagged random nonamer primer (5’-GTTTCCCACTGGAGGATA-(N9)-3’) used for unbiased reverse transcription (RNA) or initial extension (DNA). |

| SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase [14] | A high-performance enzyme for generating first-strand cDNA from viral RNA, even from challenging or degraded samples. |

| Sequenase Version 2.0 DNA Polymerase [14] | Used for efficient second-strand cDNA synthesis and DNA extension in the SISPA protocol. |

| Rapid Barcoding Kit (e.g., ONT) [14] | Enables multiplex sequencing by attaching unique barcodes to samples from different sources, reducing cost per sample. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [17] [18] | Used in the amplification step to minimize errors and reduce bias, ensuring accurate representation of the viral community. |

| Magnetic Bead-based Clean-up Kits [17] [18] | Used for post-amplification purification and size selection to remove unwanted fragments like adapter dimers and to normalize libraries. |

Implementing Robust Viral Metagenomic Protocols: From Sample to Sequence

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Filtration for Virus Enrichment

Problem: Low viral recovery after filtration.

- Potential Cause (1): Filter pore size is too small.

- Solution: Validate pore size selection based on the target virus size. For larger viruses (e.g., ~200 nm Powviruses), a 0.45 µm filter may be more appropriate than a 0.22 µm filter to prevent trapping the virus particles [19].

- Potential Cause (2): Filter membrane material causes non-specific binding of viral particles.

- Solution: Pre-treat the filter with a blocking agent like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or use low-protein-binding membrane materials (e.g., polyethersulfone) to minimize adsorption losses [20].

- Potential Cause (3): Sample viscosity leads to filter clogging.

Problem: Excessive co-concentration of impurities.

- Potential Cause: Inefficient pre-filtration or sample clarification.

- Solution: Implement a multi-step filtration process. For example, sequentially use filters with decreasing pore sizes (e.g., 1 µm → 0.45 µm → 0.22 µm) to remove particulate matter of different sizes prior to the final virus-concentrating filtration step [21].

Troubleshooting Nuclease Treatment for Virus Enrichment

Problem: Incomplete digestion of free nucleic acids.

- Potential Cause (1): Nuclease enzyme activity is inhibited by components in the sample buffer.

- Solution: Ensure the reaction buffer conditions (e.g., Mg²⁺ or Ca²⁺ concentration, pH) are optimal for the nuclease used. Dialyze or dilute the sample into the recommended reaction buffer before adding the enzyme [20].

- Potential Cause (2): Insufficient enzyme concentration or treatment time.

- Solution: Increase the amount of nuclease per volume of sample and/or extend the incubation time. Include a positive control (e.g., spiked exogenous DNA/RNA) to confirm enzymatic activity [20].

- Potential Cause (3): The nuclease is unable to access all regions of complex samples.

- Solution: Gently vortex or agitate the sample during the incubation period to ensure thorough mixing and access [21].

Problem: Significant loss of viral nucleic acids after treatment.

- Potential Cause: Viral capsid damage is allowing nuclease access to the genomic material.

Troubleshooting Ultracentrifugation for Virus Enrichment

Problem: Poor virus yield after ultracentrifugation.

- Potential Cause (1): The centrifugal force or time is insufficient for pelleting the virus.

- Solution: Confirm that the g-force and duration meet or exceed the requirements for the target virus's size and density. Refer to literature or manufacturer protocols for specific viruses. For example, protocols for seawater virus metagenomics often use forces exceeding 100,000 × g [20].

- Potential Cause (2): The virus pellet is difficult to resuspend or is lost during decanting.

- Solution: After decanting the supernatant, leave the tube inverted on a clean absorbent pad for a few minutes. Carefully resuspend the often invisible pellet in a small volume of an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS, SM Buffer) by pipetting gently along the side of the tube. Let it sit on ice for 1-2 hours before gentle pipetting [21].

Problem: High contamination with host cell debris and proteins.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate sample clarification prior to ultracentrifugation.

- Solution: Always perform a low-speed clarification step (e.g., 5,000 × g for 20 minutes) to remove large debris and cells before loading the sample for high-speed ultracentrifugation [20] [19]. Consider using a density gradient (e.g., sucrose or cesium chloride gradient) instead of a simple pelletting ultracentrifugation to better separate viruses from impurities based on buoyant density [21].

Problem: Reduced viral infectivity post-ultracentrifugation.

- Potential Cause: Mechanical forces or high g-forces damage the viral particles, especially enveloped viruses.

- Solution: For labile, enveloped viruses, consider using a sucrose cushion instead of a pelletting spin. This avoids the high shear and compressive forces associated with forming a hard pellet, helping to maintain viral integrity and infectivity [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Which single virus enrichment method is the most effective? No single method is universally best. The choice depends on your sample type and target virus. A study evaluating simple techniques on an artificial sample found that a multi-step enrichment method (e.g., combining centrifugation, filtration, and nuclease treatment) resulted in the greatest increase in the proportion of viral sequences in metagenomic datasets compared to any single method alone [20].

FAQ 2: How do I choose between a 0.22 µm and a 0.45 µm filter? The choice is a trade-off between purity and yield.

- Use a 0.22 µm filter for higher purity, as it will more effectively exclude bacteria and larger contaminants. However, it may also retain some larger viruses (e.g., Powviruses) leading to lower yields [19].

- Use a 0.45 µm filter if your target virus is larger or if you are prioritizing yield, as it will allow more viruses to pass through while still removing most bacterial cells [20].

FAQ 3: Can nuclease treatment distinguish between infectious and damaged viruses? Nuclease treatment is a key tool for this purpose. The underlying principle is that an intact viral capsid or envelope protects the genomic material. Nuclease enzymes will degrade exposed, free nucleic acids from broken viruses and host cells, while the genome within an intact, infectious particle remains shielded. This enrichment of "nuclease-protected" nucleic acid increases the relative proportion of sequences from potentially infectious viruses [20] [19].

FAQ 4: What are the major drawbacks of ultracentrifugation? While powerful, ultracentrifugation has several limitations:

- Equipment Cost: Ultracentrifuges and rotors are expensive.

- Time-Consuming: The runs are long, and protocol development can be laborious.

- Co-precipitation: Impurities like membrane vesicles or protein aggregates can pellet with the viruses [19].

- Potential for Damage: The high g-forces can damage the structure and reduce the infectivity of delicate enveloped viruses [19].

FAQ 5: Why is my metagenomic sequencing still dominated by host reads after enrichment? Even optimized enrichment protocols may not remove 100% of host nucleic acid. The remaining host reads could be due to:

- Inefficient Lysis: If host cells are not completely removed during clarification, they may lyse later in the workflow, releasing nucleic acids that are not susceptible to nuclease treatment [20].

- Protected Host Nucleic Acids: Host DNA within apoptotic bodies or extracellular vesicles may be partially protected from nucleases [19].

- Enrichment Limits: The enrichment methods are designed to increase the proportion of viral sequences, but in samples with an extremely high initial load of host material, a significant amount may persist [20]. Combining methods is the most effective strategy to mitigate this.

Comparative Data on Enrichment Methods

The table below summarizes the key advantages, disadvantages, and considerations for the three primary virus enrichment strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Virus Enrichment Techniques

| Method | Key Principle | Primary Advantage | Primary Disadvantage | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filtration | Size-based separation through a membrane with defined pore size. | Rapid and simple; easily scalable; does not require specialized equipment. | Can lose viruses that are too large for the pore size or that stick to the filter. | Initial clarification of samples; enrichment of mid-to-large sized viruses from liquid samples [20] [21]. |

| Nuclease Treatment | Enzymatic degradation of unprotected nucleic acids outside of viral capsids. | Specifically targets and removes contaminating free nucleic acids; significantly increases the relative abundance of viral sequences. | Requires intact viral capsids; optimization of buffer and enzyme concentration is critical. | Essential for most metagenomic studies; used after steps that lyse cells and release host DNA/RNA [20]. |

| Ultracentrifugation | High g-force pellets particles based on density and size. | High concentration factor; can be applied to a wide variety of sample and virus types. | Requires expensive equipment; time-consuming; can damage delicate enveloped viruses [19]. | Processing large volumes of sample (e.g., from seawater); when a high degree of concentration is needed [20] [21]. |

Experimental Workflow and Reagent Solutions

Virus Enrichment Workflow for Metagenomics

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, effective workflow for enriching viral particles from a complex sample prior to nucleic acid extraction and metagenomic sequencing. This multi-step approach synergistically combines the strengths of the individual techniques.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for implementing the virus enrichment strategies discussed.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Virus Enrichment Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethersulfone (PES) Syringe Filters | Sterile filtration for clarifying and enriching viruses from small-volume liquid samples. | Low protein binding helps maximize viral recovery [20]. |

| DNase I & RNase A | Enzymatic degradation of unprotected host and bacterial nucleic acids. | Use nuclease-free reagents; optimize concentration and incubation time for your sample type [20]. |

| Sucrose Cushion (e.g., 20%) | A density barrier during ultracentrifugation to gently pellet viruses while minimizing damage. | Particularly critical for maintaining the integrity and infectivity of enveloped viruses [19]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A universal diluent and resuspension buffer for maintaining viral stability. | Ensure isotonic and correct pH for your target virus to prevent inactivation [21]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Salt used for "salting-out" and precipitating proteins and viruses from solution. | Useful for concentrating viruses from large volumes; concentration is critical for selectivity [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Nucleic Acid Yield

Problem: Consistently low DNA/RNA yield after extraction, leading to failed downstream assays.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Suboptimal Input Sample Volume

- Solution: Determine the ideal input volume for your sample type and kit. Volumes that are too low may not contain enough target material, while volumes that exceed the kit's binding capacity can lead to clogging and inefficient binding. Refer to the manufacturer's instructions for volume limits and see the table below for experimental data [22].

- Cause: Inefficient Binding Chemistry

- Solution: Optimize the binding conditions. A recent study demonstrated that using a lysis binding buffer at pH 4.1, as opposed to pH 8.6, significantly improved DNA binding to silica beads, achieving 98.2% binding efficiency within 10 minutes [23].

- Cause: Inadequate Bead-Sample Interaction

- Solution: Improve the mixing method. "Tip-based" mixing, where the binding mix is repeatedly aspirated and dispensed, was shown to bind ~85% of input DNA within 1 minute, compared to only ~61% with standard orbital shaking [23].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Results in Viral Metagenomic Studies

Problem: High variability in pathogen detection and identification from clinical samples.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient Extraction of Low-Biomass Pathogens

- Solution: Implement a high-yield, rapid extraction method. The SHIFT-SP method (Silica bead-based High yield Fast Tip-based Sample Prep) can extract nearly all nucleic acid from a sample in 6-7 minutes, improving the detection of low-concentration targets crucial for sepsis and viral discovery [23].

- Cause: Co-extraction of Inhibitors

- Solution: Ensure thorough washing steps. Guanidinium thiocyanate-based lysis buffers are excellent at denaturing proteins and inactivating nucleases, but they are potent PCR inhibitors and must be completely removed [23].

- Cause: Using the Wrong Kit for the Application

- Solution: Select kits designed for your specific target. A forensic study found that a kit designed for genomic DNA extraction surprisingly outperformed a specialized miRNA kit in miRNA recovery and detection. Always validate your chosen kit for your specific application [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does input volume affect nucleic acid yield and quality?

The input volume directly impacts yield and the efficiency of the extraction chemistry. The table below summarizes findings from a systematic evaluation using saliva samples [22]:

| Saliva Input Volume (µL) | Impact on Nucleic Acid Recovery |

|---|---|

| 400 µL | Highest potential absolute yield; risk of overloading the column or bead binding capacity. |

| 200 µL | Often the optimal balance for high yield and purity with many commercial kits. |

| 100 µL | Good yield; a robust and reliable volume for many sample types. |

| 50 µL | Lower yield; may be necessary for precious or limited samples. |

| 25 µL | Lowest yield; significantly challenges kit efficiency and can lead to detection failures in downstream assays. |

Q2: For viral metagenomics, should I prioritize extraction speed or yield?

For viral metagenomics, yield is often more critical, especially when targeting low-abundance viruses. A high-yield method increases the probability of capturing rare viral sequences. However, a method that offers both high yield and speed, like the SHIFT-SP method, is ideal for streamlining workflows and enabling rapid diagnostics [23].

Q3: What is the most effective technology for automated nucleic acid extraction?

Magnetic bead-based technology is the largest and fastest-growing segment in automated extraction. It is preferred for its high yield, efficiency in processing diverse sample types, low contamination risk, and excellent scalability for high-throughput workflows in clinical diagnostics and genomics [24].

Q4: My miRNA results are inconsistent between studies. What could be the reason?

A major source of discrepancy is the nucleic acid extraction method. The choice of kit significantly influences miRNA recovery and subsequent detection levels (Cq values in RT-qPCR). A kit marketed for miRNA isolation does not automatically guarantee the best performance. Validation with your specific sample type and targets is essential [22].

Optimized Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for optimizing nucleic acid extraction, integrating key factors from the troubleshooting guides.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in optimized nucleic acid extraction protocols, based on the cited research.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Magnetic Silica Beads | Solid matrix for binding nucleic acids in the presence of chaotropic salts; core component of most automated, high-throughput systems [24] [23]. |

| Lysis Binding Buffer (LBB) with Chaotropic Salts | Facilitates cell lysis, denatures proteins, and creates conditions for nucleic acid binding to silica. pH 4.1 is optimal for binding [23]. |

| Wash Buffers | Typically contain ethanol or isopropanol; remove salts, proteins, and other impurities from the bead-nucleic acid complex without eluting the NA [23]. |

| Low-Salt Elution Buffer (EB) or Nuclease-free Water | Disrupts the interaction between the silica matrix and the nucleic acid, releasing the purified NA into solution. Heated elution (e.g., 62°C) can improve yield [23]. |

| Silica Column-Based Kits | Alternative solid-phase matrix; commonly used in manual protocols. Efficiency can vary significantly between kits and applications [22]. |

| Nucleic Acid Quantification Tools | Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop) for purity (A260/A280 ~1.8), Fluorometer (Qubit) for accurate concentration of specific NA types (e.g., miRNA) [22]. |

In viral metagenomics, the success of your research often hinges on the amplification method you choose. This guide provides a detailed technical comparison between two key techniques—Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) and Sequence-Independent Single Primer Amplification (SISPA)—to help you troubleshoot common experimental issues and optimize your workflow for detecting and characterizing viral pathogens.

Core Concepts at a Glance

What are MDA and SISPA?

- Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA): An isothermal amplification method that uses random hexamer primers and the highly processive φ29 DNA polymerase to amplify trace amounts of DNA. Its key feature is the ability to produce long, high-molecular-weight fragments (up to 70 kb) through rolling circle replication [25].

- Sequence-Independent Single Primer Amplification (SISPA): A PCR-based method that uses a single primer for amplification, making it sequence-independent. This allows for the amplification of both known and unknown viruses without prior sequence knowledge, though it typically produces shorter fragments compared to MDA [25].

Quick Comparison Table

| Feature | Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) | Sequence-Independent Single Primer Amplification (SISPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Isothermal amplification using rolling circle replication [25] | PCR-based amplification with a single primer [25] |

| Primary Enzyme | φ29 DNA polymerase [25] | Taq polymerase |

| Typical Input | DNA | DNA or RNA (requires reverse transcription) |

| Average Amplicon Size | Long (up to 70 kb) [25] | Shorter |

| Key Advantage | High yield and long fragments, suitable for whole-genome sequencing [25] | Unbiased amplification of unknown sequences |

| Major Drawback | High amplification bias and difficulty with complex samples [25] | Primer-derived background, shorter fragments |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Library Preparation and Amplification

1. Question: My MDA reaction resulted in high amplification bias and poor coverage of viral genomes. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

- Answer: Amplification bias in MDA is often due to non-uniform priming from random hexamers or the presence of host DNA contaminants that are preferentially amplified.

- Solution A (Increase Specificity): Implement more stringent sample pre-treatment to enrich for viral particles and deplete host nucleic acids. This includes steps like filtration (using 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm filters) and nuclease treatment (DNase I/RNase A) to degrade free-floating host DNA/RNA [25] [6].

- Solution B (Optimize Protocol): Titrate the amount of input template and reduce the number of amplification cycles if possible. Using a thermostable strand-displacing polymerase can help mitigate nonspecific amplification.

- Preventive Measure: Always include a no-template negative control to identify reagent-derived contamination, which is a significant issue in low-biomass viral metagenomics [6].

2. Question: I am observing excessive primer-dimer formation and low yield in my SISPA libraries. How can I improve the efficiency?

- Answer: Primer-dimer artifacts are a common failure in SISPA and are typically caused by suboptimal primer design or adapter-to-insert ratios [10].

- Solution A (Optimize Ligation): Precisely titrate the adapter-to-insert molar ratio. Excess adapters promote adapter-dimer formation, while too few reduce ligation yield. Ensure fresh ligase and optimal reaction conditions [10].

- Solution B (Cleanup): Use bead-based cleanup with an optimized bead-to-sample ratio to selectively remove short fragments like primer-dimers before amplification. An increased bead ratio can help [10].

- Solution C (Protocol Adjustment): Consider switching from a one-step PCR protocol to a two-step indexing approach, which has been shown to reduce artifact formation and improve target recovery [10].

3. Question: My NGS library has low complexity and a high duplicate read rate after SISPA. What steps should I take?

- Answer: High duplication rates often stem from over-amplification during the PCR step or insufficient starting material.

- Solution A (Reduce PCR Cycles): Minimize the number of amplification cycles. It is better to repeat the amplification from leftover ligation product than to overamplify a weak product [10].

- Solution B (Verify Input): Accurately quantify your pre-amplification product using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit, PicoGreen) rather than UV absorbance, which can overestimate usable material [10].

- Solution C (Check Quality): Re-purify your input sample to remove enzyme inhibitors like salts or phenol, which can lead to inefficient amplification and low library diversity [10].

Contamination and Quality Control

4. Question: I keep detecting background contaminants in my viral metagenomic data, regardless of the amplification method. What are the likely sources?

- Answer: Contamination is a critical issue in sensitive viral metagenomics. The main sources are external (reagents and laboratory environment) and internal (cross-contamination between samples) [6].

- Source 1: Extraction Kits and Reagents. Commercial kits are a major source of contaminating nucleic acids, often called the "kitome." This includes DNA in polymerases, enzymes, and even molecular-grade water [6].

- Source 2: Laboratory Environment. Contaminants can originate from the lab air, surfaces, and collection tubes [6].

- Solution: To minimize background noise:

- Process all samples in a project using the same batches/lots of reagents.

- Include negative controls (extraction and amplification) to characterize the "kitome" and subtract it bioinformatically.

- Use automated extraction systems where possible to reduce manual transfer steps and cross-contamination [6].

5. Question: My final library yield is low after amplification and cleanup. How can I diagnose the problem?

- Answer: Low yield can originate from multiple points in the workflow. Follow this diagnostic strategy [10]:

- Step 1: Check Input Quality. Use an electropherogram (e.g., BioAnalyzer) to check for degraded nucleic acid. Ensure input purity by checking 260/280 and 260/230 ratios. Re-purify the sample if contaminants are suspected [10].

- Step 2: Verify Quantification. Cross-validate concentration using fluorometry (Qubit) and qPCR, as absorbance (NanoDrop) can overestimate concentration [10].

- Step 3: Review Cleanup. An overly aggressive size selection or incorrect bead-to-sample ratio during cleanup can cause significant sample loss. Optimize these parameters for your target fragment size [10].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Workflow: SISPA for RNA Viruses

This protocol is adapted from methods used for SARS-CoV-2 whole-genome sequencing [26].

1. Sample Pre-treatment and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Viral Enrichment: Clarify the clinical sample by low-speed centrifugation. Pass the supernatant through a 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm filter to remove cells and bacteria [25].

- Nuclease Treatment: Treat the filtrate with a mixture of DNase I and RNase A to degrade unprotected nucleic acids, thereby enriching for encapsulated viral genomes [25].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Inactivate nucleases and extract total nucleic acid using a commercial kit. Automated systems are preferred to reduce contamination [6].

2. Reverse Transcription and cDNA Synthesis

- For RNA viruses, perform reverse transcription using a random hexamer primer or the SISPA primer itself. Use enzymes verified to be free of viral contaminants (e.g., Murine Leukemia Virus) [6].

3. SISPA Amplification

- Second Strand Synthesis: If needed, synthesize the second strand to create double-stranded cDNA.

- Blunt-Ending: Repair the ends of the dsDNA to create blunt ends suitable for ligation.

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate a double-stranded adapter to the blunt-ended DNA. Precisely calibrate the adapter-to-insert ratio to minimize adapter-dimer formation [10].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the adapter-ligated library using a primer complementary to the adapter sequence. Keep PCR cycles to a minimum to reduce bias and duplicate reads [10].

4. Library Cleanup and Validation

- Perform bead-based cleanup to remove primers, adapter-dimers, and other short artifacts. Validate the library using a BioAnalyzer and quantify by qPCR for accurate sequencing loading [10].

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: MDA vs. SISPA Workflow Comparison

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Amplification Failure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Amplification | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| φ29 DNA Polymerase | Core enzyme for MDA; enables isothermal, strand-displacing synthesis of long amplicons [25]. | Check for microbial DNA contaminants; requires specific reaction buffer. |

| Random Hexamer Primers | Used in MDA for unbiased priming across the genome [25]. | Quality is critical; HPLC-purified primers reduce synthesis artifacts. |

| SISPA Adapter/Primer | A single, defined oligonucleotide used for ligation and PCR amplification in SISPA. | Design affects efficiency; calibrate the adapter-to-insert ratio to minimize dimers [10]. |

| Bead-Based Cleanup Kits | For post-reaction purification and size selection (e.g., removing adapter dimers). | The bead-to-sample ratio is critical for optimal recovery and selectivity [10]. |

| DNase I & RNase A | Enzymes used in sample pre-treatment to degrade host nucleic acids and enrich for viral particles [25]. | Must be thoroughly inactivated before nucleic acid extraction to avoid degrading the target. |

| Ultrafiltration Units | For concentrating viral particles from large-volume samples (e.g., environmental water). | Membrane material (e.g., PES) can affect viral recovery; choose appropriately [25]. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Library Preparation Challenges

FAQ 1: My final library yield is unexpectedly low. What are the most common causes and solutions?

Low library yield is a frequent issue often stemming from sample quality or protocol-specific errors. The table below summarizes primary causes and corrective actions [10].

| Cause of Low Yield | Mechanism of Yield Loss | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality / Contaminants | Enzyme inhibition by residual salts, phenol, or EDTA [10]. | Re-purify input sample; ensure 260/230 ratio >1.8; use fresh wash buffers [10]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification | Overestimation of usable material by UV absorbance [10]. | Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) for template quantification; calibrate pipettes [10]. |

| Fragmentation/Inefficiency | Over- or under-fragmentation reduces adapter ligation efficiency [10]. | Optimize fragmentation parameters (time, energy); verify fragmentation profile before proceeding [10]. |

| Suboptimal Adapter Ligation | Poor ligase performance or incorrect adapter-to-insert molar ratio [10]. | Titrate adapter:insert ratios; ensure fresh ligase and buffer; maintain optimal temperature [10]. |

| Overly Aggressive Cleanup | Desired fragments are excluded during size selection [10]. | Optimize bead-to-sample ratios; avoid over-drying magnetic beads [10]. |

FAQ 2: How can I minimize contamination in viral metagenomic studies?

Contamination is a critical challenge, especially for low-biomass samples. Key strategies include [6]:

- Recognize Sources: Contamination can be external (kit reagents, laboratory environment) or internal (cross-contamination between samples). Reagent contamination ("kitome") is a major concern, with unique profiles for different kits and batches [6].

- Process Controls: Always include negative controls (e.g., water blanks) that undergo the entire extraction and library prep process to identify background contaminating nucleic acids [6].

- Standardize Reagents: Use the same batches of extraction kits and reagents for all samples within a project to control for "kitome" variation [6].

- Dedicate Workspace: Use separate pre- and post-PCR areas and dedicated equipment to reduce cross-contamination [17].

FAQ 3: My sequencing data shows high levels of adapter dimers or PCR duplicates. How can I fix this?

- For Adapter Dimers: A sharp peak at ~70-90 bp on an electropherogram indicates adapter dimers. This results from inefficient ligation or overly aggressive PCR amplification of low-input samples. Solutions include optimizing adapter-to-insert molar ratios, using bead-based cleanups with adjusted ratios to remove small fragments, and minimizing PCR cycles [10].

- For High PCR Duplication Rates: This indicates low library complexity, often from overamplification or insufficient starting material. To minimize this, use the minimum number of PCR cycles necessary, employ high-fidelity polymerases, and consider PCR-free library prep methods if input material is sufficient [10] [17].

FAQ 4: Should I choose an untargeted or targeted metagenomic approach for viral detection?

The choice depends on your goal, as the methods offer different advantages regarding sensitivity and scope [5].

| Method | Sensitivity | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted Metagenomics | Lower sensitivity, requires high sequencing depth for low viral loads [5]. | Discovery of novel or unexpected pathogens; whole-genome sequencing [5] [27]. | High host background can mask viral signals; more expensive per sample for deep sequencing [5]. |

| Targeted Panels (Enrichment) | High sensitivity; suitable for low viral loads (e.g., 60 gc/ml) [5]. | Detecting a predefined set of known viruses with high sensitivity [5]. | Cannot detect viruses not included on the panel [5]. |

Troubleshooting Guides: Step-by-Step Protocols

Protocol 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Library Preparation Failures

Introduction This protocol provides a systematic framework for diagnosing common NGS library preparation failures, from low yield to excessive adapter contamination. Following a logical flow can quickly identify root causes [10].

Materials

- BioAnalyzer, TapeStation, or similar fragment analyzer

- Fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) and spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop)

- Magnetic beads for cleanup

- Fresh reagents (enzymes, buffers)

Experimental Workflow The following diagram outlines a logical troubleshooting workflow.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Contamination-Aware Viral Metagenomics Workflow

Introduction This protocol is designed to manage the pervasive issue of contamination in viral metagenomics, enabling more confident interpretation of results, particularly in low-biomass samples [6].

Materials

- Negative control samples (e.g., nuclease-free water)

- Single batch of extraction and library prep kits

- Dedicated pre-PCR workspace

Experimental Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample and Control Setup:

- Process clinical/environmental samples alongside a negative control (e.g., nuclease-free water) that undergoes the entire workflow from extraction to sequencing [6].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Library Preparation:

- Bioinformatic Filtering:

- Sequentially analyze the data.

- First, run the sequencing data from the negative control through your taxonomic classifier.

- Then, subtract any taxonomic signals found in the negative control from the results of the actual samples [6].

Protocol 3: Selecting and Optimizing a Library Prep Method for Viral Detection

Introduction This protocol guides the selection of an appropriate library preparation method based on the sample type and research objective, comparing untargeted and targeted approaches [5].

Materials

- Illumina DNA Prep kit or similar [28]

- Twist Bioscience Comprehensive Viral Research Panel (CVRP) or similar targeted panel [5]

- RNA reverse transcription reagents (if working with RNA viruses)

Experimental Workflow The following diagram compares the key decision points for different metagenomic approaches.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Define Research Objective: Choose your path based on the workflow diagram above. Untargeted sequencing is for discovery, while targeted panels are for sensitive detection of known viruses [5] [27].

- Sample Preparation:

- For Untargeted WGS (Illumina): Use a kit like Illumina DNA Prep, which utilizes on-bead tagmentation (simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging) to simplify the workflow and reduce hands-on time. Input can range from 1 ng to 500 ng [28].

- For Targeted Enrichment: Prepare libraries using a compatible kit (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep). Then, perform hybridization capture using the viral panel (e.g., Twist CVRP) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This step enriches for viral sequences before sequencing [5].

- Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence the libraries. Note that untargeted approaches require more sequencing depth to achieve good coverage of low-abundance targets.

- For targeted data, a higher proportion of reads will be on-target, simplifying analysis and improving variant calling [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions for viral metagenomic library preparation [10] [6] [28].

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA and/or RNA from complex samples. | A major source of contaminating "kitome" DNA; using a single batch for a study is critical [6] [29]. |

| Magnetic Beads (SPRI) | Purify and size-select nucleic acids post-fragmentation and adapter ligation. | The bead-to-sample ratio is critical; an incorrect ratio can lead to loss of desired fragments or inefficient removal of adapter dimers [10]. |

| Library Prep Kits (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) | Prepare sequencing libraries via tagmentation or ligation. | Kits with on-bead tagmentation reduce hands-on time and simplify the workflow [28]. |

| Targeted Enrichment Panels (e.g., Twist CVRP) | Biotinylated probes capture and enrich for sequences from a predefined set of viruses. | Increases sensitivity by 10-100 fold for targeted viruses but will miss novel agents not on the panel [5]. |

| Unique Dual Index (UDI) Adapters | Barcode individual samples for multiplexing. | Essential for pooling multiple libraries; dual indexing helps identify and mitigate index hopping errors during sequencing [28]. |

| Universal PCR Primers | Amplify the adapter-ligated library to generate sufficient material for sequencing. | The number of PCR cycles should be minimized to reduce duplicates and bias; high-fidelity polymerases are preferred [10] [17]. |

| Negative Control (Nuclease-free Water) | Serves as a process control to monitor background contamination. | Any viral signal detected in this control should be treated as a potential contaminant and subtracted from sample results [6]. |

FAQs: Choosing Between Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing

Q1: When should I choose short-read sequencing over long-read sequencing for viral metagenomic studies?

Short-read sequencing is the preferred choice when your primary goals involve high-throughput, cost-effective sequencing for applications like viral pathogen identification, single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection, and variant calling in well-characterized viral genomes [30] [31] [32]. With read lengths typically ranging from 50 to 300 base pairs, short-read platforms like Illumina and Element Biosciences offer high accuracy (Q40+ for some platforms) and are ideal for projects requiring deep coverage at a lower cost per base [30] [31]. This makes them suitable for large-scale screening and surveillance studies.

Q2: What are the specific advantages of long-read sequencing for viral metagenomics?

Long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), are advantageous for resolving complex viral genomic regions that are challenging for short-read platforms [33]. These include regions with:

- High repetitiveness or structural variations [30] [33].

- The need for haplotype phasing to determine viral quasi-species [33].

- De novo assembly of novel viral genomes without a reference [14] [32]. ONT and PacBio can generate reads spanning thousands to tens of thousands of bases, allowing you to span repetitive regions and assemble more complete genomes [30] [33]. ONT also enables real-time sequencing and direct RNA sequencing, which can be critical for rapid outbreak surveillance [14].

Q3: Can I combine short-read and long-read data in a single study?

Yes, a hybrid approach is often highly beneficial [32]. You can leverage the low cost and high accuracy of short reads for confident SNP and mutation calling, while using long reads to resolve complex structural variations and phase haplotypes [32]. This approach is particularly powerful for de novo assembly of complex samples or for rare disease sequencing, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the viral metagenome [32].

Q4: What is the current state of long-read sequencing accuracy?

Long-read sequencing accuracy has improved dramatically. PacBio's HiFi sequencing method now delivers highly accurate reads (Q30-Q40+), with an accuracy of 99.9%, which is on par with short-read and Sanger sequencing [30]. While raw single-pass ONT reads might have a higher error rate, consensus accuracy for deep coverage ONT data is now much higher and sufficient for many applications, including identifying viral strains [30] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Library Yield in Viral Metagenomic Sequencing

Low library yield is a common issue that can lead to insufficient data for analysis. Below is a guide to diagnose and fix this problem.

Table: Troubleshooting Low Library Yield in Viral Metagenomics

| Cause of Problem | Failure Signs | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor Input Quality/Contaminants [10] | Degraded nucleic acids; inhibitors present. | Check 260/280 and 260/230 ratios via spectrophotometry (target ~1.8 and >1.8, respectively) [10]. | Re-purify input sample using clean columns or beads; ensure wash buffers are fresh [10]. |

| Inaccurate Quantification [10] | Over- or under-estimation of input material. | Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit) rather than UV absorbance for template quantification [10]. | Calibrate pipettes; use master mixes to reduce pipetting error [10]. |

| Inefficient Viral Nucleic Acid Recovery [14] | Low genome coverage despite good input quality. | Check efficiency of filtration and DNase treatment steps. | Optimize filtration (0.22 µm) and DNase treatment to remove host cells and degrade residual host DNA [14]. |

| Suboptimal Amplification [10] | Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate. | Review number of PCR cycles; check for polymerase inhibitors. | Reduce the number of amplification cycles; re-purify sample to remove inhibitors [10]. |

Problem: High Background Noise or Adapter Contamination in Data

This issue often manifests as a high proportion of reads that are not classified as the target virus, or adapter sequences appearing in the final data.

Table: Troubleshooting High Background Noise or Adapter Contamination

| Cause of Problem | Failure Signs | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Host Depletion [14] | High percentage of host (e.g., human) reads in data. | Check bioinformatics metrics for proportion of host vs. non-host reads. | Improve physical filtration (0.22 µm filter) and enzymatic digestion (DNase treatment) of samples to remove host nucleic acids [14]. |

| Adapter Dimer Formation [10] | Sharp peak at ~70-90 bp in electropherogram. | Analyze library profile on a BioAnalyzer or similar system [10]. | Titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratios; optimize ligation conditions; use bead-based cleanup with correct ratios to remove small fragments [10]. |

| Index Hopping or Cross-Contamination | Reads from one sample appear in another. | Check for unbalanced library pooling and cross-contamination between samples. | Use unique dual indexing (UDI); avoid over-cycling during library PCR; maintain physical separation during library prep. |

Workflow Diagram: Optimized Viral Metagenomic Sequencing using Long-Read Technology

The following diagram illustrates an integrated workflow for viral detection and analysis using Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT), as applied in clinical specimens [14].

Optimized Viral Metagenomic Workflow using ONT [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This table details key reagents and materials used in a viral metagenomic sequencing workflow, particularly one based on long-read technologies [14].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Metagenomic Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22 µm Filters [14] | Physical removal of host cells and debris from clinical samples. | Creates an enrichment step for viral particles in the filtrate prior to nucleic acid extraction. |

| DNase Enzyme [14] | Degradation of free-floating host genomic DNA that remains after filtration. | Reduces background host nucleic acids, increasing the relative proportion of viral sequences. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits [14] | Isolation of viral DNA and RNA from filtered samples. | Kits like QIAamp DNA Mini and Viral RNA Mini Kits are used for efficient recovery of viral nucleic acids. |

| Sequence-Independent, Single-Primer Amplification (SISPA) Primers [14] | Amplification of unknown viral sequences without prior target knowledge. | A tagged random nonamer primer (e.g., 5’-GTTTCCCACTGGAGGATA-(N9)-3’) enables unbiased amplification. |

| Rapid Barcoding Kit [14] | Multiplexing of multiple samples on a single sequencing run. | A transposase-based kit fragments DNA and attaches barcodes in a single step, reducing preparation time. |

| Polymerase for SISPA [14] | Enzymatic amplification for library preparation. | Enzymes like Sequenase Version 2.0 DNA Polymerase are used for second-strand synthesis in the SISPA protocol. |

Experimental Protocol: Multiplexed Viral Metagenomic Sequencing with Oxford Nanopore Technology

This detailed protocol is adapted from a study that successfully applied ONT sequencing to 85 clinical specimens for viral detection [14].

Objective: To detect and identify viral pathogens in clinical samples using an unbiased, multiplexed metagenomic sequencing approach on the Oxford Nanopore platform.

Materials:

- Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS)

- 0.22 µm centrifuge tube filters (e.g., Costar)

- TURBO DNase and 10X Reaction Buffer

- Nucleic acid extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit)

- SISPA Primer A (5’-GTTTCCCACTGGAGGATA-(N9)-3’)

- SuperScript IV First-Strand cDNA Synthesis System

- Sequenase Version 2.0 DNA Polymerase

- ONT Rapid Barcoding Kit

- ONT Sequencing Kit and Flow Cell (MinION or PromethION)

Procedure:

- Sample Pre-processing: Resuspend the clinical sample in HBSS to a final volume of 500 µL. Filter the solution through a 0.22 µm filter to remove host cells and debris [14].

- DNase Treatment: Mix 445 µL of the filtered sample with 50 µL of 10X TURBO DNase Buffer and 5 µL of TURBO DNase (2 U/µL). Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to degrade residual host DNA [14].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Split the DNase-treated sample. Use 200 µL for viral DNA extraction and 280 µL for viral RNA extraction, following the instructions of the respective kits. Add linear polyacrylamide (50 µg/mL) at 1% (v/v) to the lysis buffer to enhance nucleic acid precipitation efficiency [14].

- SISPA Library Preparation:

- For RNA samples: Mix 4 µL of purified RNA with 1 µL of SISPA primer A (40 pmol/µL) and perform reverse transcription. Perform second-strand cDNA synthesis using Sequenase. Treat with RNaseH [14].