Viral Diagnostic Test Verification and Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a detailed guide to the verification and validation procedures essential for developing and deploying reliable viral diagnostic tests.

Viral Diagnostic Test Verification and Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide to the verification and validation procedures essential for developing and deploying reliable viral diagnostic tests. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, from defining verification vs. validation to navigating regulatory landscapes. It explores methodological applications for established and novel techniques like metagenomic sequencing, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and outlines robust validation frameworks like the VALCOR protocol. The content synthesizes lessons from recent outbreaks, including COVID-19, and highlights emerging trends such as AI and federated learning to prepare for future diagnostic needs.

Core Principles and Regulatory Landscape of Viral Diagnostic Validation

A guide for researchers and scientists navigating the critical stages of assay development.

Core Definitions: Verification vs. Validation

| Feature | Verification | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Question | "Did we build the assay right?" [1] | "Did we build the right assay?" [1] |

| Objective | Confirm the test is designed, developed, and manufactured correctly according to predefined specifications and protocols. | Confirm the test is fit for its intended purpose and meets the needs of the end-user in a real-world setting. |

| Focus | Internal accuracy and precision; the technical performance of the assay itself. | External utility and reliability; the clinical or research effectiveness of the test results. |

| Stage of Conduct | Typically performed during the initial development and optimization of the assay, often in a controlled laboratory setting. | Typically performed after successful verification, on a larger scale that mirrors the intended use environment. |

| Primary Audience | Laboratory managers, development scientists, and technical staff. | Regulatory bodies, end-users (e.g., clinicians, researchers), and stakeholders. |

Frequently Asked Questions for Researchers

Technical & Procedural FAQs

Q1: During verification, our assay shows high precision but poor accuracy. What could be the cause? This discrepancy often points to a systematic error (bias) in your method. Troubleshoot using this protocol:

- Step 1: Calibrate Equipment. Verify the calibration of all instruments, including pipettes, centrifuges, and plate readers, using traceable standards.

- Step 2: Analyze Reference Materials. Test a certified reference material (CRM) or a known positive control from an alternate source. If the result is consistently biased, it confirms a systematic issue.

- Step 3: Review Reagent Preparation. Meticuously check the preparation, pH, and storage conditions of all buffers, standards, and reagents. A small error in concentration can cause significant bias.

- Step 4: Investigate Operator Technique. If possible, have a second experienced scientist repeat the assay to rule out individual technique as a factor.

Q2: How do I determine the appropriate sample size for a validation study? Validation sample size is determined by statistical power requirements for key claims. Follow this methodology:

- Define Key Parameters: Focus on sensitivity, specificity, and precision.

- Use Statistical Formulae: For sensitivity and specificity, use the following formula for a desired Confidence Interval (CI) width:

n = (Z^2 * p * (1-p)) / d^2where:n= required sample sizeZ= Z-score (e.g., 1.96 for 95% CI)p= expected proportion (e.g., expected sensitivity)d= desired margin of error (half the CI width)

- Incorporate Prevalence: For clinical studies, ensure your sample panel reflects the real-world prevalence of the condition. A biostatistician should be consulted to finalize the sample size.

Q3: Our validation results are inconsistent across different sample matrices (e.g., serum vs. saliva). How should we proceed? Matrix effects are a common challenge. Implement this systematic investigation:

- Protocol 1: Spike-and-Recovery Experiment.

- Spike a known quantity of the viral analyte into each problematic matrix and a control matrix (e.g., buffer).

- Measure the recovered concentration in each.

- Calculate the percentage recovery:

(Measured Concentration in Matrix / Measured Concentration in Control) * 100. - Acceptable recovery is typically 80-120%. Significant deviations indicate matrix interference.

- Protocol 2: Sample Dilution Linearity.

- Create a series of dilutions for an affected sample.

- Analyze the dilutions. If the measured analyte concentration is not proportional to the dilution factor, it suggests the presence of interfering substances that are diluted out.

- Solution: Based on the results, you may need to modify the sample preparation protocol, introduce a purification or extraction step, or specify limitations on acceptable sample matrices in your assay's instructions for use (IFU).

Compliance & Documentation FAQs

Q4: What is the minimum documentation required for a verification study? Your verification report should be a standalone document that allows for the reconstruction of the study. Essential elements include:

- Signed Protocol: The pre-approved study protocol outlining objectives, methods, and acceptance criteria.

- Raw Data: All original data, including instrument printouts, lab notebook pages, and electronic records.

- Summary Tables & Calculations: Data summarized with clear calculations for precision, accuracy, LoD, etc.

- Analysis Against Criteria: A direct comparison of results against pre-defined acceptance criteria.

- Deviations Log: A log of any deviations from the protocol, with an impact assessment.

- Conclusion: A definitive statement on whether the assay passed verification.

Q5: How should we handle a deviation or out-of-specification (OOS) result during validation? Do not discard OOS results. Follow a strict investigation procedure:

- Phase I (Laboratory Investigation): The analyst and supervisor conduct an immediate assessment to identify obvious analytical errors (e.g., calculation error, equipment malfunction, improper technique). This investigation must be documented.

- Phase II (Full OOS Investigation): If no clear assignable cause is found in Phase I, a formal investigation is launched. This includes:

- Retesting by a second analyst if possible.

- Review of reagent and sample integrity.

- A comprehensive review of the process and training records.

- Documentation: The entire investigation, including hypotheses, tests performed, and final conclusions, must be documented in the validation report. The OOS result may stand, or it may be invalidated based on clear, documented evidence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Viral Assay Development |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a gold standard with a defined, traceable quantity of the viral target or antibody. Critical for establishing assay accuracy and calibration during verification [2]. |

| Clinical Isolates & Biobanked Samples | Characterized, real-world patient samples used to challenge the assay. Essential for determining clinical sensitivity and specificity during validation studies. |

| Monoclonal & Polyclonal Antibodies | Key binding reagents for immunoassays (ELISA, LFIA). Specificity and lot-to-lot consistency of these antibodies are fundamental to the assay's performance and must be rigorously qualified [3]. |

| Molecular Standards (gBlocks, RNA Transcripts) | Synthetic nucleic acid fragments used as positive controls and for generating standard curves in PCR-based assays (qPCR, RT-qPCR). Used to determine the Limit of Detection (LoD) [2]. |

| Interferent Substances | Purified substances (e.g., bilirubin, hemoglobin, lipids, common medications) added to samples to test for assay interference. Used to establish assay robustness and specificity [2]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Concept to Validated Assay

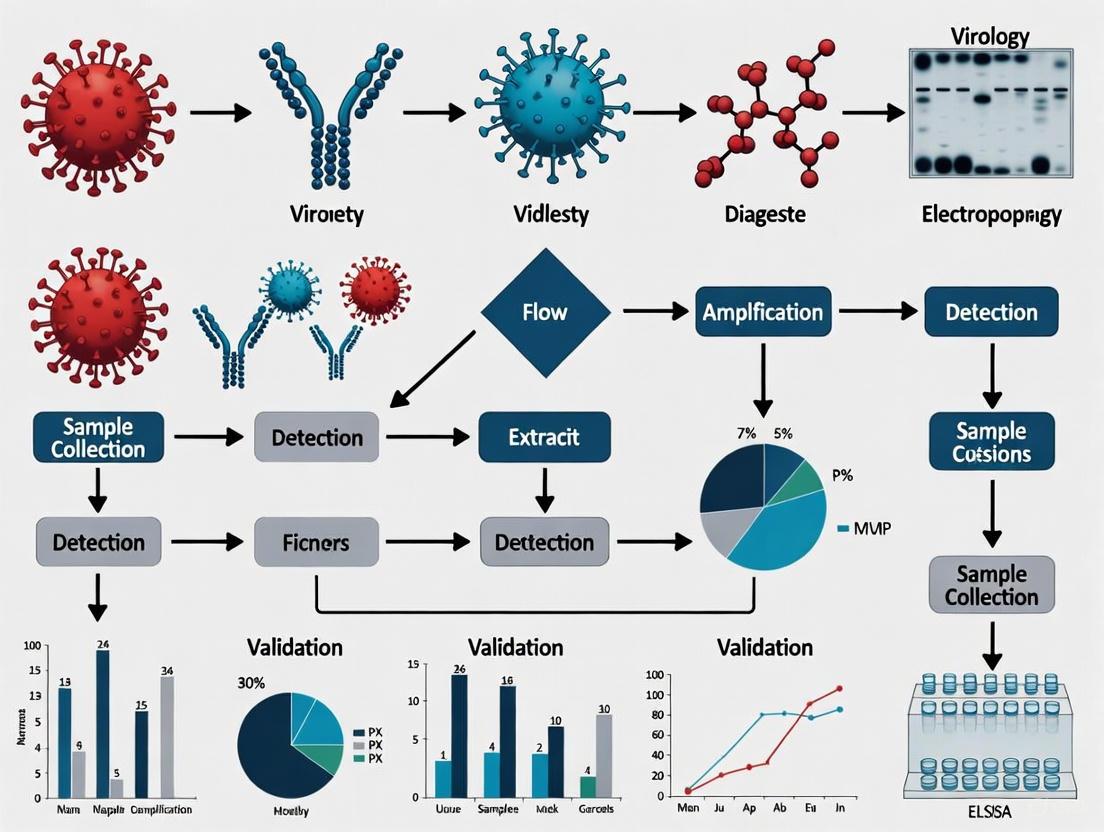

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between the key stages of assay verification and validation.

Regulatory Requirements and Quality Standards (CLIA, ISO, FDA/EUA)

Clinical laboratories operating in the United States navigate a complex regulatory landscape primarily governed by three key entities: the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Understanding their distinct roles is fundamental to maintaining compliance while ensuring test quality and reliability [4].

Key Regulatory Bodies and Their Roles

| Regulatory Body | Authority & Scope | Primary Focus | Requirement Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIA | U.S. federal regulations administered by CMS [5]. | Quality standards for all laboratory testing on human specimens [4]. | Mandatory for U.S. clinical labs [4]. |

| FDA | U.S. federal regulatory agency [4]. | Safety and effectiveness of medical devices, including in vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests [4]. | Mandatory for test manufacturers and market access [4]. |

| ISO 15189 | International voluntary organization [4]. | Quality and competence in medical laboratories; a quality management system framework [6]. | Voluntary, but demonstrates commitment to quality [4]. |

The Interplay of Regulations

- CLIA Compliance is Foundational: Any facility performing testing on human specimens for health assessment or diagnosis must hold an appropriate CLIA certificate [7]. CLIA regulations comprehensively cover the entire testing process, including personnel qualifications, quality control, proficiency testing, and quality assurance [4] [7].

- FDA's Evolving Role: While laboratories have traditionally been "users" of FDA-cleared tests, the FDA's final rule on Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs) now subjects labs creating their own tests to additional FDA regulations as "manufacturers" [4]. The FDA also grants Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for unapproved medical products during public health emergencies [8].

- ISO as the "Icing on the Cake": ISO 15189 certification is not a legal requirement but serves as a mark of excellence. It enhances a laboratory's quality management system and is often required for international work or specific contracts [4]. The standard must be updated to ISO 15189:2022 by December 2025, introducing enhanced requirements for risk management and point-of-care testing (POCT) [6].

Test Verification and Validation Protocols

Verification and validation are critical processes to ensure that a test method consistently produces accurate and reliable results for patient care.

CLIA Method Verification

For non-waived testing (moderate and high complexity), CLIA requires laboratories to establish or verify the performance specifications for each method prior to reporting patient results [7]. This process confirms that the test performs as expected in your laboratory environment.

Core Performance Specifications to Verify [7]:

| Specification | Definition | Common Verification Method |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness to the true value | Proficiency testing (PT) samples, comparison to a reference method. |

| Precision | Reproducibility of results (repeatability) | Testing replicates of the same sample. |

| Reportable Range | Span of reliable results between lowest and highest measurable values | Testing calibrators or patient samples across the claimed range. |

| Reference Range | Normal values for your patient population | Testing specimens from healthy individuals. |

Example Verification Experimental Protocol:

- Develop a Plan: The laboratory director or technical supervisor defines acceptance criteria for each performance specification based on manufacturer's claims, clinical needs, or published guidelines [7].

- Gather Materials: Collect a sufficient number of samples. A common approach is to use 20 specimens spanning the reportable range for quantitative tests, or 5 positive and 5 negative specimens for qualitative tests [7].

- Execute Testing: Run the samples according to the test's standard procedure over multiple days and by different technologists if possible to capture real-world variability.

- Analyze Data: Compare results against acceptance criteria. For example, calculate the coefficient of variation (CV%) for precision studies and assess bias for accuracy.

- Document and Approve: All procedures, raw data, and summary conclusions must be documented and approved by the laboratory director before the test is implemented for patient testing [7].

FDA Emergency Use Authorization (EUA)

During a declared public health emergency, the FDA may issue an EUA to allow the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved products. This pathway was extensively used for COVID-19 and mpox diagnostics [8].

The EUA process involves a submission from the manufacturer or developer demonstrating that the product may be effective and that the known benefits outweigh the potential risks, given the emergency context [8]. The NIH's RADx initiative provided a model for third-party, independent test verification to accelerate this process during the COVID-19 pandemic [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Our lab is already CLIA certified and we are developing a new LDT. Do we still need to follow CLIA rules, or just the new FDA LDT rules? You must follow both sets of regulations. The FDA's LDT regulations are in addition to, not instead of, CLIA requirements. Your laboratory must maintain its CLIA certification and comply with all applicable CLIA quality standards while also meeting the new FDA requirements for pre-market review, quality systems, and adverse event reporting for your LDT [4].

2. What is the most common area where labs struggle with quality and compliance? A significant challenge, especially for labs developing LDTs, is implementing the FDA's design control requirements. CLIA has no direct equivalent to these systematic processes for managing a test's design and development. Additionally, labs often face difficulties due to a lack of personnel with the expertise and time to fully grasp and implement the overlapping requirements from different regulatory bodies [4].

3. We are planning to get ISO 15189 accredited. What are the key changes in the 2022 version? The updated ISO 15189:2022 standard, which must be implemented by December 2025, introduces several key changes [6]:

- Integration of POCT requirements, previously in a separate standard (ISO 22870).

- Enhanced focus on risk management, requiring labs to implement more robust processes to identify and mitigate risks to quality.

- Updated structural and governance requirements with clearer roles and responsibilities.

4. Where do most laboratory errors occur? The majority of laboratory errors occur in the pre-analytical (test ordering, patient identification, specimen collection) and post-analytical (result reporting, data entry) phases. Less than 10% of errors happen during the actual testing or analytical phase. This highlights the importance of a robust quality assurance program that covers the entire testing process, not just the equipment in the lab [7].

5. What are the CLIA requirements for staff competency? CLIA requires laboratories to perform competency assessments for all testing personnel semiannually during the first year of employment and annually thereafter. This assessment must include six components [7]:

- Direct observation of routine test performance.

- Direct observation of instrument maintenance.

- Monitoring of test result reporting and recording.

- Review of test results, worksheets, QC, and PT records.

- Assessment of test performance through testing blind samples.

- Assessment of problem-solving skills.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and solutions essential for the development and verification of viral diagnostic tests.

| Item | Primary Function in Test R&D |

|---|---|

| Positive Control Material | Contains the target analyte (e.g., inactivated virus, synthetic RNA) to verify the test can detect a positive signal and monitor assay performance over time. |

| Negative Control Material | Confirms the test does not produce a false-positive signal due to contamination or non-specific reactions. |

| Calibrators | Standardized materials with known concentrations of the analyte used to create a calibration curve for quantitative tests, ensuring result accuracy across the measuring range. |

| Proficiency Testing (PT) Samples | External, third-party samples used to objectively compare a lab's testing performance against a reference method or peer labs, as required by CLIA [5] [7]. |

| Clinical Specimens | Residual patient samples (positive and negative) are the gold standard for clinical validation and verification studies, providing real-world matrix for evaluating accuracy [7]. |

| Third-Party Quality Control | Control materials not supplied by the test kit manufacturer, used to independently monitor the stability and reliability of the entire test system [10]. |

Experimental Workflow for Test Verification

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for verifying a new diagnostic test or method in a clinical laboratory, integrating CLIA and quality management requirements.

The Critical Role of Independent Clinical Evaluation in Public Health

FAQs: Core Principles and Processes

Q1: What is the primary purpose of an independent clinical evaluation for a viral diagnostic test? The primary purpose is to provide an impartial, objective assessment of a test's analytical and clinical performance (e.g., sensitivity, specificity) and its safety. This independent verification is crucial for validating manufacturer claims, informing regulatory decisions, and ensuring that only reliable tests are deployed in public health programs, especially during outbreaks [9].

Q2: How does independent evaluation differ from a manufacturer's own internal studies? Independent evaluation is conducted by a third party with no commercial stake in the product's success. This eliminates potential conflicts of interest and provides regulatory agencies and the public with higher-confidence, unbiased data. Programs like the NIH's RADx initiative established academic hubs to perform this "apples to apples" comparison of different technologies under standardized conditions [9].

Q3: What are the key performance parameters evaluated for a rapid diagnostic test (RDT)? A comprehensive evaluation typically assesses a battery of parameters, including:

- Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection): The lowest concentration of the virus the test can reliably detect [9].

- Clinical Sensitivity: The test's ability to correctly identify infected individuals (true positive rate) [9].

- Clinical Specificity: The test's ability to correctly identify uninfected individuals (true negative rate) [9].

- Cross-reactivity: Potential for false positives due to other similar pathogens [9].

- Repeatability: Consistency of results when the test is repeated under identical conditions [9].

- Usability: Ease of use by intended operators in real-world settings [9].

Q4: What is the regulatory significance of a Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) under the EU MDR? The Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) is a mandatory technical documentation that summarizes all clinical evidence related to a medical device, including diagnostic tests. It must demonstrate that the device is safe, performs as intended, and has a favorable benefit-risk profile. For legacy devices, a new CER under MDR requirements is often necessary due to stricter rules on demonstrating equivalence and requiring post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) data [11] [12].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Test Performance Across Sample Types

Problem: A test shows high sensitivity with nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs but inconsistent or reduced sensitivity with saliva samples.

Solution Strategy:

- Re-evaluate Sample Processing: Saliva may contain inhibitors or require specific processing steps (e.g., homogenization, heating) not needed for NP swabs. Optimize the sample preparation protocol to inactivate inhibitors and ensure the sample is compatible with the test's chemistry [13].

- Verify Viral Load Dynamics: Confirm that the sample type is appropriate for the disease stage. For some viruses, saliva may have a different viral load profile compared to NP swabs over the course of infection. Correlate test results with quantitative PCR (qPCR) data from the same sample type [13].

- Conduct a Method Comparison Study: Perform a head-to-head comparison using matched sample pairs (e.g., NP and saliva from the same patient at the same time) to statistically quantify the performance difference and establish sample-specific usage criteria [9].

Challenge 2: Demonstrating Equivalence for a Modified Test Under MDR

Problem: A manufacturer has modified a legacy test and needs to use data from the previous version to support the new one, but must prove equivalence under stricter MDR rules.

Solution Strategy: The MDR requires demonstration of equivalence in technical, biological, and clinical characteristics [11].

- Technical: Provide evidence that the devices have similar design, specifications, properties, and are used under similar conditions of use (including software algorithms) [11].

- Biological: For tests involving substances introduced into the body, demonstrate identical substances and similar biocompatibility [11].

- Clinical: Show the devices have the same clinical condition, intended purpose, same kind of user, and similar critical performance and safety data [11].

- Documentation: Complete a detailed "Equivalence Table" as guided by MDCG, providing scientific justifications for any differences and arguing why they are not clinically significant [11].

Challenge 3: Poor Clinical Sensitivity in a Point-of-Care Rapid Antigen Test

Problem: A lateral flow antigen test for a respiratory virus fails to detect infections in patients with moderate viral loads, leading to false negatives.

Solution Strategy:

- Determine the Limit of Detection (LoD): Precisely establish the test's analytical sensitivity using cultured virus or synthetic antigens in a clinically relevant matrix. Compare this LoD to the typical viral load range observed in patient populations. A test with an LoD higher than the infectious threshold will have poor clinical sensitivity [9] [14].

- Evaluate Sample Collection Kit Compatibility: Some sample collection buffers or transport media can interfere with the test's immunoassay. Test the device with samples collected in different approved media to identify potential incompatibilities [13].

- Investigate Reader-Based Detection: If the test is visually interpreted, consider transitioning to a digital reader. Fluorescent or electrochemical-based readers can objectively detect weaker signals, improving sensitivity and reducing user interpretation errors [13] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Key Evaluations

Protocol 1: Analytical Sensitivity and Limit of Detection (LoD) Study

Objective: To determine the lowest concentration of the target virus (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) that the test can detect ≥95% of the time.

Materials:

- Cultured infectious virus or synthetic target (e.g., inactivated whole virus, recombinant antigen, RNA transcript).

- Appropriate negative matrix (e.g., synthetic saliva, universal transport medium).

- Test device and required reagents.

- Standard reference method (e.g., RT-qPCR).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Serially dilute the virus or target in the negative matrix to cover a range from an expected detectable concentration down to below the expected LoD.

- Testing: Test each dilution level a minimum of 20 times (or as per regulatory guidance) with the device.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the proportion of positive results at each dilution level. The LoD is the lowest concentration at which ≥19/20 (95%) replicates test positive. Confirm this concentration in at least three independent experiments [9].

Protocol 2: Clinical Performance Evaluation (Sensitivity/Specificity)

Objective: To assess the test's ability to correctly identify infected and non-infected individuals compared to a reference standard.

Materials:

- Clinically characterized patient samples (e.g., remnant de-identified samples from clinical laboratories).

- A validated reference method (e.g., FDA-authorized PCR test for a viral target).

- Test devices.

Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Select a panel of samples that represent the test's intended use population, including positive samples with a range of viral loads and negative samples. Include samples with potential cross-reactive organisms to assess specificity.

- Blinded Testing: Test all samples with the investigational device under evaluation in a blinded manner.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate Clinical Sensitivity: (Number of True Positives / (Number of True Positives + Number of False Negatives)) × 100.

- Calculate Clinical Specificity: (Number of True Negatives / (Number of True Negatives + Number of False Positives)) × 100.

- Report results with 95% confidence intervals [9] [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and their functions in the development and evaluation of viral diagnostic tests.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Test Development & Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Antigens & Monoclonal Antibodies | Key components for developing immunoassays (e.g., lateral flow tests); used to capture and detect viral proteins. Critical for defining test specificity [13] [15]. |

| * Synthetic RNA Transcripts & DNA Oligonucleotides* | Non-infectious controls for developing and calibrating nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). Essential for determining analytical sensitivity (LoD) and verifying assay performance [9]. |

| Inactivated Whole Virus | Provides a more authentic target for evaluating test performance compared to recombinant components, as it presents antigens in a native conformation [13]. |

| Clinical Sample Panels | Well-characterized, remnant patient samples used as the gold standard for establishing clinical sensitivity and specificity during validation studies [9] [16]. |

| Microfluidic Chips & Cartridges | The physical platform for many modern "lab-on-a-chip" and molecular POC tests. They integrate sample preparation, amplification, and detection into a single, automated system [13]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Independent Test Evaluation Pathway

Clinical Evaluation Report (CER) Lifecycle

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented global demand for reliable diagnostic testing, placing immense pressure on regulatory systems and laboratory networks. The emergency use authorization (EUA) pathway enabled rapid deployment of tests but revealed significant challenges in maintaining validation standards during a crisis [17]. The experience demonstrated that sustainable validation resources—including standardized protocols, reusable reagent kits, and clear regulatory guidance—are critical for ensuring diagnostic accuracy during future outbreaks. The core lesson is that validation infrastructure must be built during peacetime to be effective during emergencies.

Regulatory Frameworks and Validation Priorities

Evolving Regulatory Pathways

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) implemented a prioritized review process for SARS-CoV-2 tests as the pandemic evolved. The agency's experience led to important policy shifts that can inform future outbreak response strategies [17]. The table below summarizes key regulatory priorities established during the pandemic:

Table 1: FDA Review Priorities for Diagnostic Tests During the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Priority Category | Description | Intended Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Innovative Technology | Tests employing novel technological approaches | Address complex diagnostic challenges with new solutions |

| Unmet Public Health Need | Tests diagnosing infection with new variants or subvariants | Fill critical gaps in testing capabilities |

| Government Partnership | Tests supported by U.S. government stakeholders (BARDA, NIH RADx) | Leverage coordinated resource investment |

| Supplemental EUA Requests | Submissions fulfilling a condition of an existing EUA | Streamline authorization for test modifications |

The FDA now strongly encourages developers to pursue traditional premarket pathways (de novo classification or 510(k) clearance) rather than relying on EUA mechanisms, reflecting a maturation of the regulatory landscape for molecular diagnostics [17].

Laboratory Modification Policies

A critical flexibility emerged for high-complexity CLIA-certified laboratories modifying EUA-authorized tests. The FDA specified conditions under which laboratories could implement modifications without new EUA submissions, provided that [17]:

- Modifications do not change the indication for use

- Changes do not alter analyte specific reagents (e.g., PCR primers/probes)

- Laboratories validate the modification and confirm equivalent performance

- Use remains limited to the implementing laboratory

This policy balance between flexibility and oversight offers a model for future outbreaks, enabling rapid adaptation while maintaining quality standards.

Diagnostic Test Validation: Protocols and Procedures

Verification of EUA COVID-19 Diagnostic Tests

The American Society for Microbiology (ASM) developed step-by-step verification procedures to help laboratories implement EUA molecular tests efficiently while ensuring accuracy [18]. These guidelines address the unique characteristics and limitations of different assay formats, including direct sample-to-answer systems, point-of-care devices, and high-complexity batched-based testing.

Table 2: Essential Components of Test Verification Protocols

| Component | Description | Application in COVID-19 Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Necessary Supplies | Reagents, controls, consumables | Identification of critical supply chain dependencies |

| Quality Control Standards | Positive, negative, internal controls | Establishing baseline performance metrics |

| Safety Requirements | Personal protective equipment, biosafety protocols | Protecting laboratory personnel during specimen handling |

| Assay Limitations | Known cross-reactivities, interference | Understanding diagnostic test boundaries |

Analytical and Clinical Validation

Comprehensive test validation requires both analytical studies (establishing test performance characteristics) and clinical studies (demonstrating real-world accuracy). The FDA provides tailored recommendations through EUA templates that reflect current thinking on validation requirements for different test types [17].

Test Validation Workflow

Research Continuity During Public Health Emergencies

Challenges in Clinical Research

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted clinical research across multiple domains. A comprehensive narrative review identified four major categories of challenges [19]:

- Researcher/Investigator Issues: Travel restrictions, reduced funding allocation to non-COVID research, and safety concerns for research staff.

- Participant and Ethical Concerns: Volunteer unwillingness, difficulties with informed consent processes, and ethical challenges in following up vulnerable patients.

- Administrative Issues: Institutional review board operational disruptions and contractual delays.

- Research Implementation Problems: Inability to conduct in-person assessments and interventions.

Remote Research Solutions

In response to these challenges, researchers developed innovative remote methodologies that can be incorporated into future validation resource planning [19]:

- Remote monitoring through phone or video visits

- Electronic data capture systems minimizing in-person contact

- Virtual platforms for participant interaction and questionnaire completion

- Modified consent processes using digital signatures and telehealth platforms

These solutions enable research continuity while maintaining ethical standards and data integrity during public health emergencies.

Diagnostic Performance and Error Mitigation

Test Performance Characteristics

Understanding the limitations of different testing methodologies is crucial for appropriate implementation and interpretation. The performance characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 tests varied significantly by methodology and timing [20].

Table 3: Performance Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Tests

| Test Type | Average Sensitivity | Average Specificity | Optimal Use Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-based RT-PCR | 58-96% [20] | ~100% [20] | Symptomatic individuals, reference testing |

| Point-of-Care Molecular | 96.9% [20] | 100% [20] | Settings requiring rapid turnaround |

| Rapid Antigen (Symptomatic) | 72.0% [20] | 99.6% [20] | Early symptom onset (first week) |

| Rapid Antigen (Asymptomatic) | 58.1% [20] | 99.6% [20] | Serial testing strategies |

Cognitive Biases in Diagnostic Decision-Making

The pandemic highlighted how cognitive biases can affect diagnostic accuracy. Key biases identified included [20]:

- Availability bias: Overdiagnosing conditions that are prominent in recent experience while missing less common conditions

- Anchoring bias: Resisting alteration of initial diagnostic impressions despite contradictory evidence

- Implicit biases: Potentially contributing to disparities in testing and diagnosis across demographic groups

Mitigation strategies include diagnostic time-outs, deliberate consideration of alternative diagnoses, and using clinical decision support systems to estimate probabilities of alternative diagnoses [20].

Instrumentation and Research Reagent Solutions

Establishing standardized, reusable reagent kits and equipment protocols is essential for sustainable validation resources. The table below outlines key research reagent solutions and their functions based on methodologies used in COVID-19 research:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Diagnostic Validation

| Reagent/Equipment Category | Function in Validation | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Control Materials | Verify test sensitivity and reproducibility | Inactivated virus, synthetic RNA controls, armored RNA |

| Negative Control Materials | Establish test specificity and identify contamination | Human specimen matrix without virus, transport media |

| Cross-Reactivity Panels | Assess assay specificity against related pathogens | Other coronaviruses, respiratory pathogens |

| Interference Substances | Identify potential assay interferents | Mucin, blood, common medications |

| Reference Standard Materials | Calibrate assays and establish quantitative ranges | WHO International Standards, FDA reference panels |

| Quality Control Reagents | Monitor assay performance over time | Low-positive, negative, internal controls |

Point-of-Care Testing Implementation

Regulatory Requirements for Point-of-Care Settings

Point-of-care testing presented unique implementation challenges during the pandemic. The CDC established specific guidance for SARS-CoV-2 rapid testing in these settings, emphasizing that [21]:

- Any site performing or interpreting tests for someone other than the individual being tested needs a CLIA certificate

- A CLIA Certificate of Waiver is appropriate if SARS-CoV-2 point-of-care testing is the only testing performed

- Sites must use FDA-authorized tests and follow manufacturer instructions precisely

Quality Assurance in Point-of-Care Testing

Implementing sustainable validation resources for point-of-care settings requires robust quality management systems. Key components include [21]:

- Pre-test processes: Proper reagent storage, specimen collection technique, and patient identification

- Testing processes: Adherence to manufacturer timing, quality control performance, and prevention of cross-contamination

- Post-test processes: Accurate result interpretation, timely reporting, and proper instrument decontamination

Point-of-Care Testing Quality Management

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed critical gaps in diagnostic validation infrastructure while simultaneously generating innovative solutions. Building sustainable resources for future outbreaks requires [17] [19] [18]:

- Standardized verification protocols that can be rapidly adapted to new pathogens

- Flexible regulatory pathways that balance speed with rigorous review

- Remote research methodologies that maintain study continuity during disruptions

- Reusable reagent platforms that minimize development timelines

- Cognitive debiasing strategies that improve diagnostic accuracy

By institutionalizing these lessons into peacetime operations, the global research community can establish the validation resources needed to respond more effectively to future public health emergencies.

Methodologies in Practice: From Standard PCR to Metagenomic Sequencing and AI

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs) are foundational tools in modern molecular diagnostics, detecting viral pathogens by amplifying and identifying their genetic material. These tests were crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection, exemplifying their critical role in infectious disease management [22]. The verification and validation of these tests are essential components of diagnostic development, ensuring they meet rigorous performance standards for clinical use. Within this framework, NAATs primarily fall into two methodological categories: thermocycling-dependent methods like Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and isothermal amplification methods that operate at a constant temperature [23]. The validation process must critically address analytical factors such as the limit of detection (LOD) and false-positive rates, which are vital for establishing test reliability and informing clinical decision-making [22]. This guide provides a structured technical resource for researchers and developers navigating the experimental and troubleshooting phases of NAAT development and application.

Core Principles and Techniques

NAATs encompass a range of techniques designed to amplify specific nucleic acid sequences from pathogens. The two main approaches are defined by their temperature requirements during amplification.

- RT-PCR and PCR-Based Methods: These tests require thermal cycling between different temperatures for denaturation, annealing, and extension. They are typically performed in a laboratory setting and are considered the gold standard for sensitivity [23].

- Isothermal Amplification Methods: These tests amplify nucleic acids at a single, constant temperature, simplifying instrumentation and potentially enabling point-of-care use. Common isothermal techniques include [24] [25] [23]:

- Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)

- Nickin endonuclease amplification reaction (NEAR)

- Transcription-mediated amplification (TMA)

- Helicase-dependent amplification (HDA)

- Recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA)

- Strand displacement amplification (SDA)

Comparative Analysis of Key NAAT Platforms

The table below summarizes the fundamental operational differences between a classic PCR method and a representative isothermal method, LAMP, which is increasingly prominent in molecular diagnostics [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Standard PCR and LAMP Characteristics

| Property | PCR | LAMP |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Process | Cycles through three temperature steps (e.g., 95°C, ~60°C, 72°C) | Occurs at a constant temperature (60–65°C) |

| Denaturation | Achieved via high heat | Performed by strand-displacing polymerase |

| Equipment | Requires a thermocycler | Does not require a thermocycler; can use a water bath or heat block |

| Typical Reaction Time | At least 90 minutes to results | Often less than 30 minutes to results |

| Sensitivity | Can detect targets at nanogram levels | Can detect targets at femtogram levels |

| Result Visualization | Typically requires gel electrophoresis | Can be visualized via colorimetric change or turbidity |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges encountered during NAAT development and validation, providing evidence-based solutions.

No or Weak Amplification

Table 2: Troubleshooting No or Weak Amplification

| Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient Template | - Verify template quantity and quality; consider increasing input amount within the assay's validated range [26].- For low-abundance targets, increase PCR cycles up to 40 [27]. |

| PCR Inhibitors | - Dilute the template to reduce inhibitor concentration [27].- Purify the template using a dedicated clean-up kit [27].- Use polymerases known for high inhibitor tolerance, such as Bst for LAMP or Terra PCR Direct for PCR [25] [27]. |

| Suboptimal Reaction Conditions | - For PCR: Lower the annealing temperature in 2°C increments, increase extension time, or optimize Mg2+ concentration [26] [27].- Ensure all reaction components are thoroughly mixed [26]. |

| Enzyme or Reagent Issues | - Include a positive control to confirm reagent functionality [27].- Ensure the DNA polymerase is appropriate for the application (e.g., proofreading for high fidelity, strand-displacing for LAMP) [26] [25]. |

Nonspecific Amplification or High Background

- Problematic Primer Design: Use BLAST alignment to check for off-target complementarity, especially at the 3' ends. Redesign primers if necessary, ensuring they lack complementary sequences or consecutive G/C nucleotides at the 3' end to prevent primer-dimer formation [27].

- Non-Stringent Reaction Conditions:

- For PCR: Increase the annealing temperature stepwise, use a "touchdown PCR" protocol, or reduce the number of cycles [26] [27].

- For all NAATs: Reduce the amount of template or primer concentration if they are in excess [26] [27].

- Use Hot-Start Enzymes: Employ hot-start DNA polymerases that remain inactive until a high-temperature activation step, which suppresses nonspecific amplification initiated during reaction setup [26].

- SYBR Green Artifacts in qPCR: If using SYBR Green, check the melt curve for multiple peaks, which can indicate primer-dimers or nonspecific products. Optimize primer design and reaction conditions to ensure specificity [28].

False Positives and Contamination Control

Contamination is a critical concern in high-sensitivity NAATs, especially in a validation laboratory setting.

- Sources of Contamination: The most common sources are amplicons from previous reactions (carryover contamination), cloned DNA, sample-to-sample cross-contamination, and exogenous DNA in the laboratory environment or reagents [27].

- Prevention Strategies:

- Physical Separation: Establish physically separated "pre-PCR" and "post-PCR" areas. Equipment, pipettes, lab coats, and reagents dedicated to the pre-PCR area should never enter the post-PCR area [27].

- Workflow and Reagents: Use aerosol-filter pipette tips. Aliquot reagents into small portions for single-use and store them separately from DNA samples and amplicons [27].

- No-Template Controls: Always run a control reaction that omits template DNA to monitor for contamination [27].

- Decontamination Protocols: If contamination occurs, decontaminate workstations and pipettes with 10% bleach and/or UV irradiation. UV light can cross-link and damage residual DNA, but exposure time should be limited for reagents or equipment that may be sensitive to UV degradation [27].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Real-Time LAMP Assay for Tuberculosis Detection

A 2025 validation study detailed a real-time LAMP (rt-LAMP) assay for pulmonary tuberculosis, providing a model protocol for isothermal test development [29].

- Primer Design: Primers were designed targeting the mpt64 gene using LAMP designer software. The final primer set included Forward and Backward Inner Primers (FIP, BIP), Outer Primers (F3, B3), and Loop Primers (LF, LB) [29].

- Reaction Setup:

- Master Mix (per reaction): 1.6 µM FIP/BIP, 0.4 µM F3/B3, 0.2 µM LF/LB, 1X WarmStart LAMP Master Mix, 2 µM SYTO 16 fluorescent dye, nuclease-free water to volume.

- Procedure: 20 µL of master mix was aliquoted, and 5 µL of extracted DNA template was added. The reaction was run at 65°C for 40 minutes in a real-time PCR machine configured for isothermal fluorescence reading [29].

- Limit of Detection (LOD) Determination:

- A recombinant plasmid containing the mpt64 target was created and serially diluted.

- The DNA copy number per µL was calculated using the formula:

Number of copies/µl = (M x 6.022x10^23 x 10^-9) / (n x 660)where M is the DNA concentration in ng/µl and n is the plasmid length in base pairs. - The LOD was determined to be 10 copies/µl by testing each dilution in triplicate [29].

- Clinical Performance:

- The assay was validated on 350 patient samples against a microbiological reference standard (MGIT culture).

- Sensitivity: 89.36% (95% CI: 76.9–96.45%)

- Specificity: 94.06% (95% CI: 90.77–96.44%) [29]

Workflow Diagram: NAAT Experimental and Validation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for the development and validation of a NAAT, from sample processing to result interpretation, incorporating key quality control steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful development and troubleshooting of NAATs depend on the selection of appropriate reagents. The table below lists essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for NAAT Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Bst DNA Polymerase | The primary enzyme for LAMP. Derived from Bacillus stearothermophilus, it has strong strand-displacement activity for isothermal amplification [25]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | A modified enzyme for PCR that is inactive at room temperature, preventing nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation during reaction setup [26]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) are the building blocks for DNA synthesis. They must be provided in balanced, equimolar concentrations to prevent misincorporation [26]. |

| Magnesium Ions (Mg²⁺) | A critical cofactor for DNA polymerases. Its concentration must be optimized, as it influences enzyme activity, primer annealing, and amplicon specificity [26]. |

| Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences designed to be complementary to the target pathogen's genome. Careful design is paramount for specificity and efficiency [26]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., SYTO 16, SYBR Green) | Intercalating dyes that bind double-stranded DNA, allowing for real-time monitoring of amplification in platforms like qPCR and rt-LAMP [28] [29]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A pure, contaminant-free solvent used to prepare reaction mixes, ensuring no enzymatic degradation of nucleic acids or primers occurs. |

| Positive Control | A well-characterized sample containing the target sequence, used to verify that the entire testing process is functioning correctly [27]. |

Sample Preparation and Enrichment Protocols for Metagenomic Sequencing

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) offers a comprehensive, unbiased method for detecting nearly all potential pathogens—viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites—in a single assay, making it particularly valuable for diagnosing infections with non-specific clinical presentations such as meningitis, encephalitis, and respiratory syndromes [30]. The reliability of these results is fundamentally dependent on robust sample preparation and enrichment protocols, which are crucial for enhancing pathogen nucleic acid recovery and minimizing background host and non-target material [31] [32] [33].

The following sections detail the foundational and advanced methodologies, provide a visual workflow, and address common troubleshooting challenges encountered during library preparation.

Core Sample Preparation & Enrichment Methodologies

Foundational mNGS Workflow for CSF

This protocol, validated in a CLIA-certified laboratory for diagnosing neurological infections, outlines the core steps for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) processing [30].

Experimental Protocol [30]:

- Microbial Enrichment: Begin with sample processing to enrich for microbial content.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total nucleic acids from the sample.

- Library Construction:

- Use the Nextera library construction method.

- Perform two rounds of PCR amplification.

- Library Pooling: Pool libraries in equimolar concentrations.

- Sequencing: Sequence on an Illumina instrument, targeting 5 to 20 million sequences per library.

- Bioinformatics Analysis: Analyze raw sequence data using the SURPI+ pipeline, which includes:

- Filtering algorithms to confirm pathogen hits.

- Taxonomic classification for species-level identification.

- A graphical user interface (SURPIviz) for result review and reporting.

Performance Metrics: This assay demonstrated a 92% sensitivity and 96% specificity in identifying causative pathogens from CSF samples when compared to conventional microbiological testing [30].

Advanced Enrichment via Probe Capture for Respiratory Pathogens

Probe-based enrichment significantly improves sensitivity, especially for viruses, by selectively isolating pathogen-derived nucleic acids. The following protocol was benchmarked using 40 clinical nasopharyngeal swabs [31].

Experimental Protocol [31]:

- Sample Lysis: Use chaotropic salt-based buffer combined with bead beating.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Perform a magnetic bead-based semi-automatic extraction of total nucleic acids (TNA).

- Library Preparation: Generate Illumina sequencing libraries from DNA or RNA.

- Probe Capture Enrichment: Subject libraries to in-solution capture enrichment using a panel of biotinylated tiling RNA probes (120nt) targeting 76 respiratory pathogens.

- Sequencing: Sequence enriched libraries on Illumina or Nanopore platforms.

Performance Metrics [31]:

- The overall detection rate increased from 73% to 85% after probe capture with Illumina sequencing.

- Probe capture boosted unique pathogen reads by 34.6-fold for DNA sequencing and 37.8-fold for cDNA sequencing.

- This method significantly improved genome coverage, particularly for viruses.

Optimized Viral Metagenomics Protocol for Clinical Samples

This protocol was optimized for various clinical samples (plasma, urine, throat swabs) and uses a combination of physical and enzymatic methods to enrich for viral particles [32] [33].

Experimental Protocol [33]:

- Sample Pre-processing: Centrifuge samples at 2,000 RPM for 10 minutes.

- Filtration: Pass the supernatant through a 0.45-μm PES filter to remove cells and larger debris.

- Nuclease Treatment (Crucial Step):

- Treat the filtrate with a nuclease mix (DNase and RNase A) for 1 hour at 37°C.

- This step degrades free-floating host and bacterial nucleic acids, while capsid-protected viral nucleic acids remain intact.

- Remove nuclease activity by protease treatment.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit) with high starting volumes (500-1000 μl) eluted into a small volume (25 μl) to maximize concentration.

- Unbiased Amplification: Perform reverse transcription and random amplification of RNA and DNA in separate reactions to ensure complete genome coverage.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram synthesizes the key steps from the cited protocols into a generalized, optimized workflow for metagenomic sequencing of clinical samples, highlighting critical enrichment and preparation stages.

Troubleshooting Common Library Preparation Issues

Common problems during NGS library preparation can derail an entire metagenomic sequencing run. The table below outlines frequent issues, their root causes, and proven corrective actions [34].

| Problem Category | Typical Failure Signals | Common Root Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Input / Quality | Low yield; smear on electropherogram; low complexity [34]. | Degraded DNA/RNA; contaminants (phenol, salts); inaccurate quantification [34]. | Re-purify input; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit); check purity ratios (260/280 ~1.8) [34]. |

| Fragmentation & Ligation | Unexpected fragment size; sharp ~70-90 bp peak (adapter dimers) [34]. | Over-/under-shearing; improper adapter-to-insert molar ratio; poor ligase performance [34]. | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter ratios; ensure fresh enzymes and buffers [34]. |

| Amplification & PCR | Overamplification artifacts; high duplicate rate; bias [34]. | Too many PCR cycles; carryover enzyme inhibitors; primer exhaustion [34]. | Reduce PCR cycles; re-purify sample to remove inhibitors; optimize primer and polymerase conditions [34]. |

| Purification & Cleanup | High adapter-dimer signal; sample loss; carryover of salts [34]. | Incorrect bead-to-sample ratio; over-dried beads; pipetting errors [34]. | Precisely follow cleanup protocols; avoid over-drying beads; implement technician checklists [34]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and kits used in the validated protocols, providing researchers with essential materials for establishing these methods.

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics / Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Nextera / Illumina DNA Prep [30] [35] | Library construction for NGS. | Tagmentation-based library prep; widely considered a "gold-standard" for metagenomics [35]. |

| Biotinylated RNA Probe Panels [31] | Targeted enrichment of pathogen sequences. | Tiling probes (120nt) targeting 76 respiratory pathogens; boosts sensitivity and read depth [31]. |

| QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit [33] | Nucleic acid extraction from clinical samples. | Optimized for viral nucleic acid recovery from plasma, swabs, and urine [33]. |

| SURPI+ Software Pipeline [30] | Bioinformatic analysis of mNGS data. | Rapid pathogen identification and taxonomic classification; includes graphical interface for clinical review [30]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I improve the detection of viruses with low abundance in respiratory samples? A1: Probe-based enrichment is highly effective. Using a panel targeting 76 respiratory pathogens has been shown to increase the detection rate from 73% to 85% and boost unique viral reads by nearly 40-fold, significantly improving sensitivity for pathogens like Influenza B and Rhinovirus [31].

Q2: What is the critical step in preparing plasma samples for viral metagenomics? A2: Nuclease treatment is crucial. After filtration, treating the sample with DNase and RNase degrades unprotected host and bacterial nucleic acids. This enriches for capsid-protected viral genomes, dramatically improving the signal-to-noise ratio in subsequent sequencing [33].

Q3: My NGS libraries have a very low yield. What are the most likely causes? A3: Low yield most commonly stems from (1) poor input quality/degradation, (2) contaminants inhibiting enzymes, or (3) inaccurate quantification leading to suboptimal reaction conditions. Always use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) over UV absorbance and re-purify samples if contaminants are suspected [34].

Q4: How do I set thresholds for reporting a pathogen in a clinical mNGS assay to avoid false positives? A4: Establishing rigorous thresholds is key. For bacteria, fungi, and parasites, using a normalized metric like RPM-r (Reads per Million in sample / RPM in no-template control) can minimize false positives from background contamination. An RPM-r threshold of 10 was validated to maximize accuracy. For viruses, requiring reads from ≥3 distinct genomic regions adds stringency [30].

Validation Frameworks for Antigen-Detection Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs)

Core Validation Concepts for Laboratory Professionals

The reliability of Antigen-Detection Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) hinges on a rigorous validation framework, which distinguishes between verification (confirming a commercial test's stated performance) and validation (establishing performance for laboratory-developed tests or novel applications) [36] [37]. For CE/IVD-labeled tests, laboratories must perform verification to confirm precision under local conditions [36]. In contrast, "home-brewed" or extensively modified tests require full validation to establish their sensitivity, specificity, precision, and linearity [36]. This process is foundational for integrating RDTs into clinical virology and public health practice, ensuring that tests perform as expected in their intended operational context.

A unified framework for diagnostic test evaluation during emerging outbreaks emphasizes the critical feedback loop between test accuracy evaluation, public health modeling, and intervention impact [38]. This approach is essential for responding to epidemics, where test deployment is urgent and pathogen characteristics may evolve rapidly.

Key Differences: Verification vs. Validation

Table: Comparison of Verification and Validation Requirements

| Aspect | Verification (CE/IVD-labeled Tests) | Validation (Home-brewed Tests) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Confirm manufacturer's stated performance claims [36] | Establish complete performance characteristics [36] |

| Sensitivity Assessment | Typically not required if manufacturer's claims are verified [36] | Required using 10 positive and 10 low-positive specimens [36] |

| Specificity Assessment | Typically not required if manufacturer's claims are verified [36] | Required using 20 negative but potentially cross-reactive specimens [36] |

| Precision Evaluation | Required (intra-assay precision with 3 replicates of 1 positive and 1 low-positive sample) [36] | Required [36] |

| Linearity Evaluation | Required for quantitative NAT systems [36] | Required for quantitative systems [36] |

Diagram: Diagnostic Test Implementation Decision Pathway

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Technical Issues and Resolutions

Q1: Our laboratory is encountering inconsistent results between different lots of the same RDT brand. What is the systematic approach to identify the root cause?

A: Inconsistent inter-lot performance suggests potential issues with manufacturing quality control or component stability. Implement this investigative protocol:

- Documentation Review: Verify that all lots were stored under identical conditions (temperature, humidity) and are within their expiration dates [39].

- Controlled Re-testing: Select a panel of well-characterized specimens (positive, negative, and low-positive). Test these specimens across the different lots in parallel, using the same operator, equipment, and reagents to control for variables [36].

- Component Analysis: Systematically assess all test components, not just the cassette. Critical findings from malaria RDT evaluations highlight that defects in accessories are a common source of error [40]. Specifically check:

- Buffer Vials: Visually inspect for uniformity and measure the volume in multiple vials from each lot. Variations in buffer volume or concentration can dramatically alter test performance [40].

- Blood Transfer Devices (BTDs): Evaluate the mean blood volume transferred by BTDs from each lot. Substandard BTDs can deliver non-uniform blood volumes, leading to false negatives (insufficient blood) or illegible results (excess blood) [40].

- Escalation: Report findings to the manufacturer. If defects are confirmed, request replacement of defective lots. The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued notices regarding variable buffer volumes, recommending against procurement until defects are resolved [40].

Q2: We observe faint test lines at low antigen concentrations that are difficult for personnel to interpret consistently. How can we objectively define the limit of detection (LoD) and reduce subjectivity?

A: Subjective interpretation of faint lines is a major source of inter-operator variability. Implement a quantitative, laboratory-anchored framework to define the LoD objectively [41].

- Digital Signal Capture: Use a standardized method (e.g., cell phone camera with fixed settings) to capture test strip images [41].

- Signal Intensity Quantification: Process images using software to calculate the normalized signal intensity of the test line against the background. This converts visual band intensity into a continuous, objective variable [41].

- Modeling Dose-Response: Fit the normalized intensity data against antigen concentration using a model (e.g., Langmuir-Freundlich adsorption model:

I = kC^b / (1 + kC^b), whereIis intensity andCis concentration) to characterize the test's signal response [41]. - Establish Probabilistic LoD: Incorporate the statistical distribution of your user population's visual acuity. The LoD should be defined as the antigen concentration at which a predefined percentage of trained users can reliably detect the test line, bridging laboratory data with real-world use [41].

Q3: What are the primary causes of false-negative results in antigen RDTs, and how can our validation protocol address them?

A: False negatives primarily stem from antigen levels falling below the test's detection threshold. A robust validation protocol must account for this.

- Low Parasitemia/Viral Load: Sensitivity decreases significantly when pathogen concentration is low [42]. This is a fundamental limitation of RDTs.

- Target Genetic Variability: For tests targeting specific proteins (e.g., HRP2 for malaria), deletions in the corresponding gene can lead to false negatives [42]. This is a well-documented issue with Plasmodium falciparum in certain regions.

- Prozone Effect: Very high antigen concentrations can sometimes saturate the antibodies, leading to a false negative or a faint line [42]. This is less common but should be considered.

- Inadequate Sample Collection: Insufficient sample material is a frequent user error [39].

- Validation Solution: During validation, ensure your positive sample panel includes specimens with low antigen concentrations (e.g., high qRT-PCR cycle thresholds for SARS-CoV-2) to empirically determine the test's clinical sensitivity curve and its lower limit of reliable detection [36] [41].

Q4: Our point-of-care antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 shows good sensitivity in lab evaluations but poorer performance in real-world deployment. What factors should we re-examine in our validation framework?

A: This discrepancy highlights the difference between ideal laboratory conditions and real-world application. Expand your validation framework to include:

- User Usability Studies: Evaluate performance with intended users (e.g., healthcare workers, self-testing public) rather than only trained laboratory personnel. The "naked-eye limit of detection" varies across the user population and must be characterized [41].

- Environmental Robustness Testing: Validate test performance under various environmental conditions (temperature, humidity) that mimic storage and use settings in homes, clinics, or community centers [40] [39].

- Specimen Type and Quality: Test performance using specimens collected in real-world settings, which may differ in quality from those collected by highly trained phlebotomists or clinicians [36].

- Modeling Real-World Performance: Use a Bayesian predictive model to compose the laboratory-derived signal-to-concentration model, the user LoD distribution, and a viral-load calibration (e.g., from qRT-PCR Ct values). This generates a predicted Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) curve as a function of viral load, which can be compared against real-world outcomes [41].

Advanced Technical Troubleshooting

Table: Advanced Troubleshooting for Research & Development

| Problem | Investigation Methodology | Potential Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Noise | Inspect test strip for red cell adherence; review conjugate pad composition and sample buffer lytic agents [42]. | Optimize buffer formulations; include surfactants to reduce non-specific binding. |

| Poor Line Intensity | Characterize kinetic curve of signal development; test antibody pair affinity and concentration [41]. | Source higher-affinity antibody pairs; increase test line antibody concentration. |

| Low Specificity/Cross-Reactivity | Test against a panel of potentially cross-reactive organisms or antigens [36]. | Identify and replace non-specific antibodies; add blocking agents to the buffer. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol for Determining Limit of Detection (LoD)

Objective: To empirically determine the lowest concentration of target antigen that the RDT can reliably detect.

Materials:

- Recombinant target protein or inactivated virus with known concentration.

- Negative clinical matrix (e.g., nasal swab medium, blood).

- Pipettes and serial dilution equipment.

- Timers.

Methodology:

- Prepare Dilution Series: Perform a log-scale serial dilution of the antigen in the negative clinical matrix, covering a range from above the expected LoD to below it.

- Testing: Test each dilution level multiple times (e.g., n=20 replicates) as per the RDT's Instructions for Use (IFU) [36].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the proportion of positive results at each concentration. The LoD is defined as the lowest concentration at which ≥95% of replicates test positive [36] [41].

- Advanced Quantification (Recommended): For a more rigorous analysis, use digital imaging to measure normalized test line intensity. Model the dose-response relationship using the Langmuir-Freundlich isotherm to understand the dynamic range and precisely interpolate the LoD [41].

Protocol for Assessing Precision (Repeatability)

Objective: To measure the variation in results when the same sample is tested multiple times under identical, within-run conditions.

Materials:

- One positive sample with a high antigen concentration.

- One low-positive sample near the LoD.

- Multiple test kits from the same lot.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Aliquot the two characterized samples.

- Intra-assay Precision: Test each sample (high positive and low positive) at least three times within a single run [36].

- Analysis: For qualitative tests, all results must be concordant (e.g., all positive). For quantitative tests (if signal is measured), calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for the signal intensities. A CV of <10-15% is generally acceptable, though manufacturer claims should be verified.

Protocol for Specificity and Cross-Reactivity Testing

Objective: To confirm the test does not generate false-positive results with samples containing potentially cross-reacting organisms or interfering substances.

Materials:

- A panel of 20 negative clinical specimens [36].

- Cultured isolates or recombinant proteins of related pathogens (e.g., other coronaviruses for SARS-CoV-2 tests, or other Plasmodium species for malaria tests) [42].

Methodology:

- Panel Testing: Test the panel of negative specimens. The test should demonstrate ≥99% specificity with this panel [36].

- Cross-Reactivity Challenge: Test the RDT with high concentrations of the related pathogens. A true-specific test should yield a negative result.

- Genetic Diversity: For viruses with high mutation rates, check primer and probe sequences against genomic databases to ensure they target conserved regions, minimizing the risk of false negatives due to genetic drift [36].

Diagram: Quantitative RDT Evaluation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

A standardized set of reagents and materials is critical for reproducible RDT validation and development.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RDT Development

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance in Validation/Development |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Antigen Proteins | Used for calibration curves, LoD determination, and linearity studies. Provides a standardized, safe material for initial assay characterization [41]. |

| Inactivated Virus or Cultured Parasites | Essential for assessing test performance with intact pathogen structures, which may better mimic clinical samples than recombinant proteins alone [41]. |

| Clinical Specimen Panels | Well-characterized, banked clinical samples (positive, negative, low-positive) are the gold standard for determining clinical sensitivity and specificity [36]. |

| Monoclonal/Polyclonal Antibodies | The core capture and detection reagents. Affinity and specificity of antibody pairs directly determine the sensitivity and specificity of the RDT [42]. |

| Lateral Flow Strip Components (Nitrocellulose membrane, conjugate pad, sample pad, absorbent pad) | The physical platform for the assay. Membrane pore size, flow rate, and pad compositions must be optimized for consistent performance and minimal background [42]. |

| Specimen Collection Swabs & Buffer | The initial sample collection and preservation. Swab material and buffer composition can impact antigen stability and release, critically influencing test accuracy [40] [39]. |

Leveraging AI and Federated Learning for Enhanced Diagnostic Accuracy and Data Privacy

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists developing AI-driven diagnostic tools for viral diseases. The guidance below addresses common technical challenges within a federated learning framework, contextualized by the requirements of rigorous diagnostic test verification and validation procedures [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can we ensure our federated learning model generalizes well across different hospitals with varied data types?

A primary challenge in federated learning is data heterogeneity. To ensure robust generalization:

- Utilize Synthetic Data: Employ Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create synthetic, high-quality medical datasets. This supplements limited or imbalanced real-world data from individual sites, bolstering model resilience and reducing overfitting [43].

- Implement Advanced Architectures: Leverage modern model architectures like Vision Transformers for image-based diagnosis, which can capture complex patterns more effectively than conventional CNNs, or MLP-Mixer for processing image patches [43] [44].

- Standardize Preprocessing: While data remains decentralized, agree on common pre-processing steps (e.g., image normalization, sequence alignment standards) with all participating sites to minimize technical variation.

FAQ 2: Our model performs well locally but the global federated model is inaccurate. What could be the cause?

This is a classic sign of client drift, often due to non-IID (Independently and Identically Distributed) data across clients [45]. Solutions include:

- Algorithm Selection: Use aggregation algorithms designed for heterogeneity. While Federated Averaging (FedAvg) is common, consider alternatives like FedProx (addresses system and statistical heterogeneity) or SCAFFOLD (uses control variates to correct client drift) [46].

- Check Data Distribution: Use tools to analyze the data distribution across participating sites without sharing raw data. This can help diagnose severe imbalances.

- Stratified Sampling: If possible, implement stratified sampling on the client side before local training to ensure each local dataset better represents the overall population distribution.

FAQ 3: How can we make the predictions of our "black-box" AI model trustworthy for clinicians?

For clinical adoption, model interpretability is crucial. Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) techniques:

- Post-hoc Explanations: Apply methods like LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) or SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to generate feature importance maps (e.g., highlighting regions in a chest X-ray that contributed most to a COVID-19 diagnosis) [43].

- Incorporate Transparency: Choose model architectures that offer a degree of inherent interpretability where possible. The use of XAI fosters transparency, making AI decisions clear and reliable for healthcare practitioners [43].

FAQ 4: We need to incorporate new, incrementally arriving data from ongoing surveillance. How can we do this without retraining from scratch?

This challenge requires combining federated learning with continual learning.

- Cross-Paradigm Fusion: Implement a framework that integrates both methodologies. Federated learning preserves privacy across institutions, while continual learning allows the model to learn from new data (new viral strains, new imaging protocols) without catastrophically forgetting previously acquired knowledge [44].

- Techniques like LwF: Algorithms such as Learning without Forgetting (LwF) can be integrated into the federated learning process. This approach uses knowledge distillation to retain performance on old tasks while learning new ones [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Convergence is Slow or Unstable During Federated Training

- Check 1: Local Learning Rates. Excessively high local learning rates can cause divergence. Reduce the local learning rate and observe the global model's stability across communication rounds [46].

- Check 2: Client Participation. If only a small fraction of clients participates in each round, convergence can be slow and noisy. Increase the number of clients selected per round, if computationally feasible.

- Check 3: Data Quality on Clients. Internally validate data labels and quality on local clients. Inconsistent labeling between sites is a major source of instability. The use of a third-party test verification hub, like the ACME POCT in the RADx program, can provide a benchmark for model performance [9].

Problem: Data Privacy Concerns Remain Despite Using Federated Learning

- Check 1: Secure Aggregation. Ensure that the model update aggregation process on the central server uses a secure multi-party computation protocol. This prevents the server from identifying the source of any individual update.

- Check 2: Differential Privacy. Add calibrated noise to the model updates (gradients) before they are sent from the local client to the server. This provides a mathematical guarantee of privacy, protecting against certain types of inference attacks [46].

- Check 3: Encrypted Communication. Verify that all communication channels between clients and the central server are encrypted using standard protocols like TLS/SSL.

Problem: Performance Degradation When Identifying New or Emerging Pathogens

- Check 1: Feature Selection. For genomic pathogen identification, ensure your model uses an automatic, effective feature selection mechanism tailored to recognize novel patterns in genome sequences, rather than relying solely on known markers [46].

- Check 2: Model Architecture for Genomics. Use a dedicated deep federated learning model for genome sequences. For example, a DFL-based LeNet model has shown 99.12% accuracy in identifying new infections from genomic data while preserving privacy [46].

- Check 3: Out-of-Distribution Detection. Implement modules that can detect when an input sample (e.g., a genome sequence or medical image) is too different from the training data, allowing the model to return "uncertain" as a safety feature, similar to the InfEHR system [47].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies applying AI and FL to infectious disease diagnostics.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI/Federated Learning Models in Infectious Disease Diagnostics

| Application / Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity/Recall | Specificity/Precision | Key Metric | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFL-LeNet for New Infection ID (Genomes) | 99.12% | Recall: 98.04% | Precision: 98.23% | F1-Score: 96.24% | [46] |

| Federated COVID-19 Screening (CXR Images) | Up to 99.6% | N/A | N/A | Global Accuracy | [48] |

| MLP-Mixer + LwF (Multi-class Thoracic Infection) | 54.34% | N/A | N/A | Average Accuracy | [44] |

| InfEHR for Neonatal Sepsis Prediction (EHR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12-16x better ID than current methods | [47] |

| Federated Model (FedCNNAvg) for Malaria | 98.92% | N/A | N/A | Accuracy | [44] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing a Federated Learning Model for Medical Image Analysis