Viral Genetic Diversity and Evolutionary Dynamics: Mechanisms, Analysis, and Clinical Implications for Drug Development

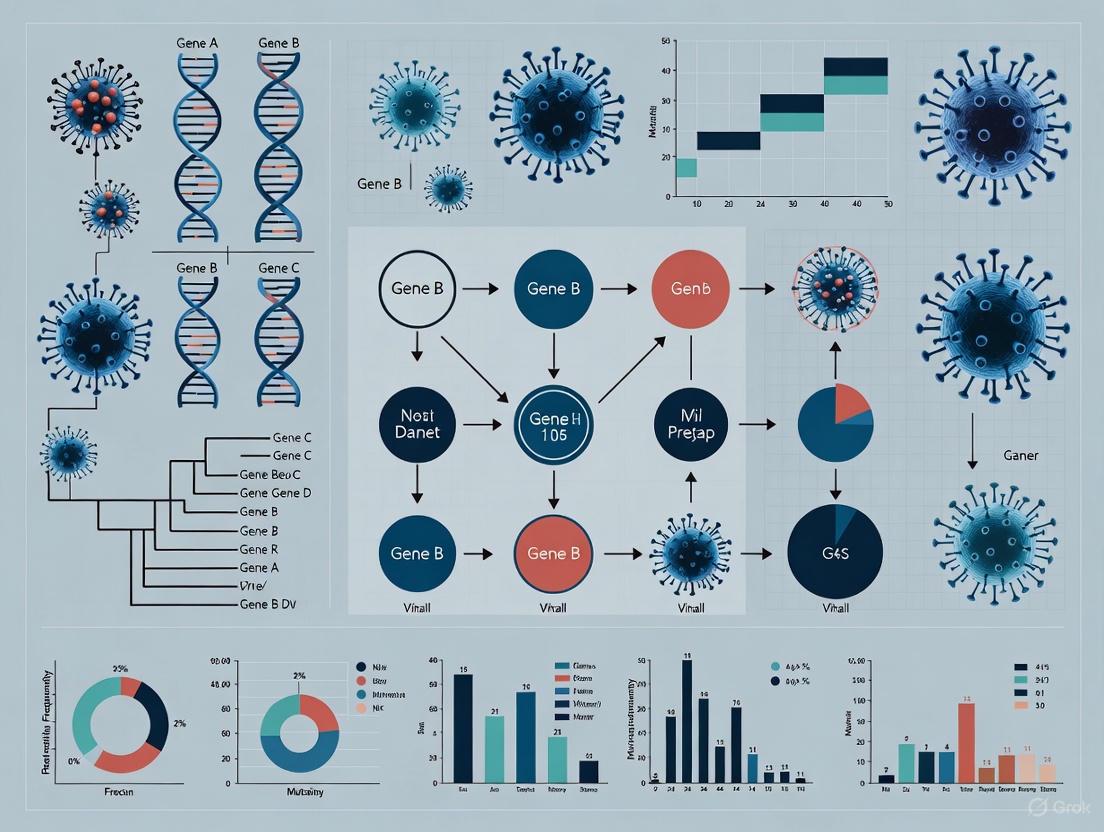

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the mechanisms generating viral genetic diversity and the evolutionary relationships that shape viral populations.

Viral Genetic Diversity and Evolutionary Dynamics: Mechanisms, Analysis, and Clinical Implications for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the mechanisms generating viral genetic diversity and the evolutionary relationships that shape viral populations. It explores the foundational principles of viral evolution, from error-prone replication and recombination to the formation of quasispecies. The review critically assesses modern methodologies, including high-throughput sequencing and computational models, for analyzing viral diversity and tracking transmission dynamics. A dedicated focus on troubleshooting addresses challenges such as sequencing errors and the emergence of drug resistance. Finally, the article offers a comparative analysis of different viral families and validation techniques, synthesizing key insights to inform the development of novel therapeutics, vaccines, and public health strategies against fast-evolving viral pathogens.

The Engines of Viral Diversity: Unraveling Mechanisms of Mutation and Evolution

Error-Prone Replication and the Absence of Proofreading in RNA Viruses

Error-prone replication is a hallmark of RNA viruses, serving as a primary mechanism for generating genetic diversity and facilitating rapid evolution. Unlike DNA-based organisms, most RNA viruses lack the sophisticated proofreading mechanisms that ensure high-fidelity genome replication. This inherent capacity for error generates heterogeneous viral populations, or quasispecies, which provide the raw material for adaptation to new hosts, evasion of immune responses, and development of antiviral resistance [1] [2]. The high mutation rates observed in RNA viruses stem from the error-prone nature of their replication machinery, particularly the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), which does not possess intrinsic proofreading capability in most viral families [1].

The absence of robust proofreading mechanisms in RNA viruses creates a fundamental evolutionary trade-off. While high mutation rates generate diversity that enables rapid adaptation, they also risk accumulating deleterious mutations that can compromise viral fitness. Most RNA viruses navigate this balance by maintaining mutation rates just below the error threshold, beyond which the viral population would accumulate too many lethal mutations and face extinction—a phenomenon known as lethal mutagenesis [2]. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for research on viral evolution and the development of antiviral strategies that exploit this vulnerability.

Molecular Basis of Error-Prone Replication in RNA Viruses

The Error-Prone RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp)

At the core of error-prone viral replication is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), which catalyzes the synthesis of new RNA strands using viral RNA as a template. Unlike cellular DNA polymerases, RdRp exhibits low fidelity due to its structural flexibility and limited capacity for nucleotide selection. The enzyme frequently incorporates incorrect nucleotides during genome replication because it lacks the precise molecular recognition domains found in high-fidelity polymerases [1]. This intrinsic infidelity is compounded by the absence of exonuclease activity that could remove misincorporated nucleotides in most RNA viruses.

The error rate of viral RdRp is quantitatively staggering, with misincorporation occurring as frequently as once per 10^3 to 10^5 nucleotides polymerized [1]. For a typical RNA virus with a 10,000-base genome, this translates to approximately one mutation in every newly synthesized genome. When considering that a single infected cell may produce thousands of viral particles, the potential for genetic diversity becomes enormous—a single infection can theoretically generate thousands of viral mutants [1].

Comparative Analysis of Nucleic Acid Polymerase Fidelity

Table 1: Comparison of Fidelity Across Different Nucleic Acid Polymerases

| Polymerase Type | Template | Proofreading Activity | Error Rate (per nucleotide incorporated) | Biological System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) | RNA | Generally absent | 10^-3 to 10^-5 | Most RNA viruses |

| DNA-dependent DNA polymerase | DNA | Present (3'-5' exonuclease) | 10^-7 to 10^-9 | Cellular organisms |

| RNA-dependent DNA polymerase (Reverse transcriptase) | RNA | Limited/None | 10^-4 to 10^-5 | Retroviruses |

| Coronavirus RdRp | RNA | Present (nsp14-ExoN) | ~10^-6 to 10^-7 | Coronaviridae |

The dramatic difference in fidelity between RNA viral replication and cellular DNA replication, spanning several orders of magnitude, underscores the unique evolutionary strategy of RNA viruses [1]. This high error rate has profound implications for viral evolution, pathogenesis, and therapeutic interventions.

The Coronavirus Exception: A Unique Proofreading System

Molecular Architecture of the Coronavirus Proofreading Complex

Coronaviruses represent a notable exception among RNA viruses due to their possession of a unique proofreading mechanism. This system centers on non-structural protein 14 (nsp14), a bifunctional enzyme containing an N-terminal 3'-to-5' exoribonuclease domain (ExoN) and a C-terminal N7-methyltransferase domain [3]. The ExoN domain functions as the proofreading component, recognizing and removing misincorporated nucleotides during RNA synthesis. The exonuclease activity is not autonomous but requires interaction with nsp10, which acts as a crucial cofactor that stimulates the proofreading function [3].

The proofreading complex operates in concert with the viral RdRp (nsp12) and other replication enzymes. During RNA synthesis, the replication complex occasionally incorporates incorrect nucleotides. The ExoN domain of nsp14 recognizes these mismatches and excises the erroneous nucleotides from the nascent RNA chain, allowing RdRp to continue with correct nucleotide incorporation [3] [4]. This proofreading capacity significantly enhances replication fidelity compared to other RNA viruses and enables coronaviruses to maintain the largest known RNA genomes, ranging from approximately 26 to 32 kilobases [3].

Experimental Evidence for Coronavirus Proofreading Function

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence Demonstrating Coronavirus Proofreading Activity

| Experimental Approach | Key Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| ExoN deletion mutants | 15- to 20-fold increase in mutation frequency; attenuation of viral virulence | Confirmed ExoN's role in maintaining replication fidelity and virulence |

| Susceptibility to mutagenic agents (e.g., 5-fluorouracil) | ExoN-deficient SARS-CoV showed 160-fold reduction in replication with 5-FU; ExoN+ virus was protected | Demonstrated ExoN provides protection against lethal mutagenesis |

| Genome sequencing after mutagen treatment | ExoN-deficient virus: 3,648 mutations; ExoN-proficient virus: 259 mutations | Quantified the protective effect of proofreading against mutagenesis |

| Biochemical characterization of nsp14 | Exonuclease activity dependent on nsp10 cofactor; structural studies revealed catalytic mechanism | Elucidated the molecular basis of proofreading |

The critical evidence for coronavirus proofreading comes from studies with ExoN deletion mutants. When researchers deleted the ExoN domain from SARS-CoV, the resulting virus exhibited dramatically increased sensitivity to mutagens like 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [4]. While wild-type virus replication was relatively unaffected by 5-FU treatment, ExoN-deficient viruses experienced a 160-fold reduction in replication efficiency and accumulated far more mutations—3,648 mutations in ExoN-deficient populations versus only 259 mutations in proofreading-competent viruses [4]. These findings conclusively demonstrated that ExoN functions as a proofreading enzyme that protects coronaviruses from lethal mutagenesis.

Methodologies for Studying Viral Replication and Mutation Dynamics

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Mutation Rates

Mutagen Sensitivity Assay

Purpose: To evaluate viral susceptibility to mutagenic compounds and assess proofreading activity. Procedure:

- Infect susceptible cells (e.g., Vero E6) with wild-type and proofreading-deficient viruses at low MOI

- Treat cultures with serial dilutions of mutagenic agents (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, ribavirin)

- Harvest viral supernatits at 24-48 hours post-infection

- Quantify viral titers by plaque assay or TCID50

- Extract viral RNA for genome sequencing and mutation frequency analysis

Interpretation: Proofreading-deficient viruses exhibit significantly greater replication impairment and higher mutation accumulation in the presence of mutagens compared to wild-type viruses [4].

Viral Population Sequencing and Mutation Frequency Analysis

Purpose: To quantitatively measure mutation rates and patterns in viral populations. Procedure:

- Generate viral stocks from individual clones or limited passages

- Infect cells at low MOI to avoid population bottlenecks

- Extract viral RNA from progeny virions

- Perform reverse transcription and PCR amplification of multiple genome regions

- Sequence using next-generation sequencing platforms (Illumina, Nanopore)

- Analyze sequence data to identify mutations relative to consensus

Key Calculations:

- Mutation frequency = Total mutations / (Genome size × Number of sequences)

- Transition/transversion ratios to identify mutation patterns [3] [4]

Mathematical Modeling of Replication-Mutation Dynamics

Mathematical models provide powerful tools for understanding viral replication dynamics and mutation accumulation. A standard approach incorporates key parameters including infected cell death rate (δ), rate constant for virus infection (β), and maximum rate constant for viral replication (γ) [5] [2].

The basic model structure includes:

- Target cells (T)

- Infected cells (I)

- Viral load (V)

The dynamics can be described by: dT/dt = -βTV dI/dt = βTV - δI dV/dt = γI - βTV - cV

Where the within-host reproduction number at symptom onset (RS0 = γ/δ) represents the average number of newly infected cells produced by a single infected cell [5]. This framework allows researchers to identify regimes of error catastrophe and lethal mutagenesis, where antiviral treatments can drive viral extinction by pushing mutation rates beyond sustainable thresholds [2].

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying RNA Virus Replication and Proofreading

| Research Reagent | Application/Function | Example Use in Proofreading Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenic nucleoside analogs (5-FU, ribavirin) | Induce lethal mutagenesis; test proofreading efficiency | Comparing susceptibility of ExoN+ vs ExoN- viruses [4] |

| ExoN-active site inhibitors | Specifically block proofreading activity | Investigating consequences of transient proofreading inhibition |

| Recombinant nsp14-nsp10 complex | Biochemical characterization of proofreading | In vitro exonuclease assays; structural studies |

| Reverse genetics systems | Generate isogenic viruses with specific mutations | Creating ExoN catalytic site mutants [3] |

| Next-generation sequencing platforms | Quantify mutation frequency and patterns | Comprehensive mutation profiling after mutagen treatment |

| Mathematical modeling software | Simulate replication-mutation dynamics | Predicting error thresholds and lethal mutagenesis conditions [2] |

Visualization of Coronavirus Proofreading Mechanism

Implications for Antiviral Development and Therapeutic Strategies

The unique features of RNA virus replication, particularly the absence of proofreading in most families and its presence in coronaviruses, present distinct opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Two primary strategies have emerged:

Lethal Mutagenesis

This approach exploits the inherently high mutation rates of RNA viruses by further increasing the error frequency beyond the sustainable threshold. Nucleoside analogs such as ribavirin and favipiravir can incorporate into viral RNA during replication, causing additional mutations that ultimately lead to viral extinction through error catastrophe [1] [2]. Mathematical models predict that successful lethal mutagenesis requires reducing viral replication while simultaneously increasing mutation rates, creating a therapeutic window where viral load declines due to accumulated deleterious mutations [2].

Proofreading-Targeted Therapies

For coronaviruses, the ExoN proofreading activity represents a unique drug target. Inhibiting ExoN could sensitize coronaviruses to existing nucleoside analogs, creating combination therapies that first disable proofreading and then induce lethal mutagenesis [3] [4]. Research has demonstrated that coronaviruses lacking functional ExoN become highly susceptible to mutagens, supporting this therapeutic strategy [4]. Combination approaches using proofreading inhibitors with mutagenic agents may overcome the resistance conferred by the coronaviral proofreading system.

The timing of antiviral intervention is critical, particularly for rapidly replicating viruses like SARS-CoV-2, which reaches peak viral load just 2.0 days after symptom onset—significantly earlier than SARS-CoV (7.2 days) or MERS-CoV (12.2 days) [5]. Treatments that block de novo infection or virus production are most effective when initiated before this viral peak, while therapies promoting cytotoxicity of infected cells show less sensitivity to treatment timing [5].

Error-prone replication and the general absence of proofreading mechanisms in RNA viruses represent fundamental biological properties with profound implications for viral evolution, pathogenesis, and therapeutic development. The coronaviral exception, with its unique ExoN-mediated proofreading system, demonstrates how virological rules can be broken while providing valuable insights into the balance between genomic stability and adaptability. Understanding these mechanisms at molecular, population, and theoretical levels provides the foundation for innovative antiviral strategies that exploit the delicate balance RNA viruses maintain between mutational freedom and informational integrity. Future research directions include developing specific ExoN inhibitors, optimizing combination therapies that induce lethal mutagenesis, and further elucidating the structural basis of replication fidelity across diverse RNA virus families.

The Impact of Recombination and Reassortment on Genome Organization

Genetic recombination and reassortment are fundamental molecular processes that drive viral evolution and generate genetic diversity. Recombination refers to the rearrangement of DNA or RNA sequences through the breakage and rejoining of nucleic acid strands, while reassortment is a specific type of recombination occurring in segmented viruses where entire genome segments are exchanged during co-infection [6] [7]. These mechanisms facilitate the evolution of viral pathogens by enabling them to overcome selective pressures, adapt to new hosts, evade immune responses, and develop resistance to antiviral therapies [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these processes is crucial for predicting emerging viral threats, designing broad-spectrum therapeutics, and developing effective vaccines. This technical guide examines the impact of recombination and reassortment on viral genome organization within the broader context of viral genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships research.

Fundamental Mechanisms

Molecular Basis of Recombination

Genetic recombination involves the exchange of genetic material between two viral genomes, creating novel chimeric sequences. The process can be categorized into distinct types based on the underlying mechanism and sequence requirements:

Homologous recombination occurs between sequences with extensive similarity, where the crossover happens at the same position in both parental strands [7]. This process can be reciprocal, producing an even exchange of genetic material, or nonreciprocal (gene conversion), where one chromosome donates a sequence to another without receiving anything in return [7].

Non-homologous (illegitimate) recombination occurs at different sites in the parental strands with little to no sequence homology, often producing aberrant genetic structures [6]. This type of recombination typically involves microhomologies of just a few base pairs at the recombination junctions [7].

Site-specific recombination is mediated by sequence-specific recombination enzymes, often encoded by viruses or transposable elements, and may rely on very short stretches of homology between interacting nucleic acids [7].

For RNA viruses, the predominant mechanism is copy-choice recombination, where the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase switches templates during genome replication, generating a chimeric progeny genome [8]. The rate of RNA recombination varies dramatically among virus families, with some negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses exhibiting effectively clonal populations, while some positive-sense RNA viruses and retroviruses display high recombination rates that can exceed mutation rates per nucleotide [8].

Reassortment in Segmented Viruses

Reassortment is a specialized form of genetic exchange unique to viruses with segmented genomes. When two different viral strains co-infect a single cell, they can package a mixture of genomic segments from both parents into progeny virions, creating novel genotypes in a single replication cycle [9]. This process is particularly significant for evolutionary leaps because it allows for the simultaneous exchange of multiple genes, potentially creating viruses with new antigenic and pathogenic properties [9].

The compatibility of segments from different parental strains determines the success of reassortment outcomes. Protein-protein interactions and segment-packaging signals often constrain which segment combinations can form functional viruses [8]. Some viruses exhibit non-random segregation patterns, where certain gene combinations are preferentially maintained due to functional compatibilities that enhance fitness [8].

Figure 1: Reassortment Mechanism in Segmented Viruses. During coinfection, genomic segments from parental viruses mix and are repackaged into progeny virions with novel gene combinations.

Impact on Viral Genome Organization

Structural Consequences for Viral Genomes

Recombination and reassortment exert profound influences on viral genome organization, potentially leading to both adaptive benefits and structural constraints:

Generation of novel gene arrangements: Recombination can produce genomes with unusual organizations, as demonstrated in snake arenaviruses where recombinant segments featured two intergenic regions and superfluous content while remaining capable of stable replication and transmission [10].

Alteration of regulatory elements: Crossovers within non-coding regions can modify transcription regulation signals, replication origins, or packaging signals, potentially altering viral replication kinetics and host range [6].

Segment compatibility constraints: In segmented viruses, reassortment is constrained by the need for maintained functional interactions between gene products. Surface proteins often exhibit co-evolutionary patterns with low reassortment rates, as seen in influenza A virus where HA, NA, and MP genes tend to reassort together to maintain compatibility [11].

Modular genome evolution: Recombination facilitates the exchange of functional modules between viruses, allowing for the acquisition of new capabilities. The GPC gene of snake arenaviruses appears to have been acquired through recombination with filoviruses or avian retroviruses, representing a significant alteration of genome organization [10].

Quantitative Assessment of Recombination and Reassortment

Table 1: Recombination and Reassortment Frequencies Across Virus Families

| Virus Family | Genome Type | Recombination Rate | Reassortment Potential | Key Factors Influencing Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroviridae (HIV) | ssRNA-RT | High (exceeds mutation rate) [6] | Not applicable | Template switching between two copackaged genomes [8] |

| Orthomyxoviridae (Influenza) | (-)ssRNA segmented | Low for RNA recombination [6] | High [11] | Segment compatibility, host species [11] |

| Arenaviridae | (-)ssRNA segmented | Variable; documented in snake arenaviruses [10] | Documented in natural infections [10] | Coinfection frequency, host factors [10] |

| Picornaviridae | (+)ssRNA | High in some members [6] | Not applicable | Polymerase processivity, RNA secondary structure [8] |

| Herpesviridae | dsDNA | High homologous recombination [6] | Not applicable | Host recombination machinery, DNA repair pathways [6] |

Table 2: Documented Reassortment Events in Segmented Viruses

| Virus | Segment Number | Reassortment Efficiency | Constrained Segments | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus | 8 | High in avian strains [11] | HA, NA, MP (co-evolve) [11] | Tagged virus system [9] |

| Mammalian orthoreovirus | 10/11 | Non-random segregation [8] | L1, M1 constraints [9] | HRM genotyping [9] |

| Snake arenaviruses | 2 | Widespread in natural infections [10] | S segment dominance [10] | Metagenomic sequencing [10] |

| Rotavirus | 11 | Variable | NSP genes [8] | Electrophoretic mobility [9] |

Methodologies for Detection and Analysis

Experimental Approaches for Reassortment Quantification

Accurate quantification of reassortment requires sensitive methods that can distinguish highly similar parental genomes while minimizing selection biases:

Tagged virus systems: The construction of well-matched parental viruses differing only by silent mutations enables reassortment quantification without fitness differences confounding results. These systems use high-resolution melt (HRM) analysis to distinguish segment origins based on single-nucleotide differences in short amplicons (65-110 bp) [9].

High-resolution melt (HRM) genotyping: This post-PCR method detects subtle differences in amplicon melting curves caused by synonymous mutations identifying parental origins. The method is sensitive enough to detect single-nucleotide changes, making it ideal for quantifying reassortment between highly similar viruses [9].

Epitope-tagged reporters: For tracking infection and segment origin in mixed infections, epitope tags (e.g., 6xHIS, HA) can be inserted into viral proteins with flexible linkers (GGGGS) to avoid interference with protein folding. This enables immunological detection of parental origins in reassortant viruses [9].

Metagenomic sequencing: Deep sequencing of viral populations from natural infections allows comprehensive detection of recombination and reassortment events without prior assumptions about parental strains. This approach identified 210 genome segments grouping into 23 L and 11 S genotypes in snake arenaviruses, revealing extensive diversity [10].

Computational Detection Methods

Bioinformatic tools are essential for identifying recombination and reassortment events from sequence data:

TreeSort algorithm: This novel tool uses the phylogeny of a selected viral segment as a reference to identify branches where reassortment has occurred with high probability. It reports specific gene segments involved in reassortment and their divergence from prior pairings, enabling analysis of thousands of whole genomes [11].

Phylogenetic incongruence: Comparison of gene trees across different genome segments can reveal reassortment events through topological conflicts. This approach has revealed elevated reassortment rates in highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b during 2020-2023 [11].

Recombination breakpoint detection: Algorithms such as those implemented in RDP, GENECONV, and Bootscan can identify recombination breakpoints by scanning for significant changes in sequence similarity or phylogenetic relationships along genome alignments [6].

Figure 2: Workflow for Detecting Recombination and Reassortment Events. Integrated experimental and computational pipeline for identifying and characterizing viral genome rearrangements.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Recombination and Reassortment

| Reagent/Cell Line | Specification | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHK-T7 cells | Baby hamster kidney cells stably expressing T7 RNA polymerase [9] | Reverse genetics for segmented viruses | Enables plasmid-based recovery of recombinant viruses |

| A549 cells | Human lung epithelial cells (ATCC CCL-185) [9] | Influenza and reovirus reassortment studies | Permissive for respiratory viruses, relevant cell type |

| L929 cells | Spinner-adapted mouse fibroblast cells [9] | Reovirus propagation and reassortment assays | High-yield virus production in suspension culture |

| Tagged virus systems | Wild-type and variant pairs with synonymous mutations [9] | Quantitative reassortment measurement | Eliminates selection bias in reassortment frequency |

| HRM genotyping kits | High-resolution melt analysis reagents [9] | Discrimination of segment origins | Detects single-nucleotide differences in amplicons |

| Epitope-tagged constructs | HA, 6xHIS tags with GGGGS linkers [9] | Tracking parental segment origin | Allows immunological detection without disrupting protein function |

Evolutionary Consequences and Research Applications

Impact on Viral Evolution and Emergence

Recombination and reassortment significantly accelerate viral evolution through several mechanisms:

Emergence of novel pathogens: Reassortment can create viruses with new antigenic properties and host ranges, as demonstrated by the 2009 influenza A virus pandemic that resulted from reassortment between avian, swine, and human strains [9].

Alteration of virulence and pathogenesis: Recombinant viruses may acquire mutations that enhance pathogenicity. Arenavirus recombination is thought to have given rise to ancestral S segments of New World rodent arenaviruses, potentially influencing their disease potential [10].

Expansion of host range: Genetic exchanges can facilitate cross-species transmission by providing viruses with genetic combinations necessary to infect new host species. The Western equine encephalitis virus emerged through recombination between two parental viruses [6].

Immune evasion and drug resistance: In HIV, recombination rapidly shuffles resistance mutations across populations, accelerating the development of multidrug resistance and complicating treatment strategies [6].

Research Applications and Therapeutic Implications

Understanding recombination and reassortment processes has direct applications in public health and therapeutic development:

Vaccine design: Identifying constrained gene partnerships through reassortment analysis informs the design of broad-coverage vaccines. The low reassortment frequency between surface protein genes in influenza suggests these should be targeted together in vaccine formulations [11].

Antiviral development: Knowledge of recombination hotspots and mechanisms aids in designing inhibitors that target these processes or their products, potentially reducing viral evolutionary capacity.

Pandemic risk assessment: Tools like TreeSort enable real-time tracking of reassortment patterns across hosts, identifying novel virus combinations with heightened pandemic potential for prioritized response [11].

Molecular epidemiology: Recombination and reassortment signatures serve as markers for tracking transmission pathways and understanding outbreak dynamics during viral investigations.

Recombination and reassortment are powerful drivers of viral evolution that profoundly impact genome organization and diversity. These processes facilitate rapid viral adaptation through the generation of novel genetic combinations, influencing pathogenesis, host range, and antigenic properties. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms is essential for predicting viral emergence, designing effective countermeasures, and developing strategies to combat antiviral resistance. Continued advancement in detection methodologies, particularly tagged virus systems coupled with sensitive genotyping and computational tools like TreeSort, will enhance our ability to monitor and respond to the evolving threat landscape of recombinant viruses. Integrating knowledge of these fundamental genetic processes into research and public health practice remains crucial for addressing current and future viral challenges.

Viral quasispecies represent a fundamental paradigm in virology that describes RNA viruses and certain DNA viruses as dynamic, complex populations of closely related genetic variants. This population structure, governed by high mutation rates during replication, enables remarkable adaptability and has profound implications for pathogenesis, drug resistance, and therapeutic development. This whitepaper examines the theoretical foundations of quasispecies theory, explores advanced methodologies for their characterization, and discusses the clinical consequences of this unique evolutionary strategy. By integrating quantitative data, experimental protocols, and computational approaches, we provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for investigating viral quasispecies in the context of viral genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships.

Viral quasispecies are defined as dynamic collections of closely related viral genomes subjected to continuous genetic variation, competition among variants, and selection of the most fit distributions in a given environment [12] [13]. This population structure contrasts with classical views of viral species as static entities with defined nucleotide sequences, instead characterizing them as mutant swarms or mutant clouds where genetic diversity is the norm rather than the exception [14] [15]. The quasispecies concept has become the most adequate framework for understanding RNA virus dynamics because it explicitly incorporates limited copying fidelity as a key parameter in its mathematical formulation and emphasizes the critical role of mutant distributions during replication [13].

The biological significance of quasispecies stems from their contribution to viral adaptability and evolutionary potential. At any given time, a viral population maintains a reservoir of both genotypic and phenotypic variants, providing what has been termed adaptive pluripotency [14] [15]. This diversity enables rapid response to selective pressures such as host immune responses, antiviral therapies, or environmental changes. The quasispecies structure has practical consequences for disease control, as interventions targeting a single viral genotype may select for pre-existing resistant mutants within the mutant spectrum [16].

Theoretical Framework and Evolutionary Concepts

Historical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

Quasispecies theory originated from two independent lines of inquiry: theoretical work on molecular evolution by Manfred Eigen and Peter Schuster, and experimental observations of RNA bacteriophage Qβ populations by Charles Weissmann and colleagues [16] [14] [15]. Eigen's pioneering mathematical treatment addressed the evolution of molecules that replicated with regular production of error copies, seeking to develop a model for self-organization and adaptability of primitive replicons at the origin of life [13].

The core quasispecies model is described by the set of differential equations:

This mathematical formulation describes the time change of the fraction of the population of the ith mutant sequence (xi) where (fj) is the replication rate of the jth mutant, (Q_{ji}) is the probability of mutation from sequence j to i, and (Ω(x)) denotes the average fitness of the population [16]. The model portrays viral populations as organized mutant spectra dominated by a master sequence—the genotype with the highest replicative capacity—surrounded by a cloud of closely related variants.

Error Threshold and Sequence Space

A fundamental concept arising from quasispecies theory is the error threshold, which represents the maximum mutation rate compatible with maintenance of genetic information [16] [14]. When mutation rates exceed this threshold, the master sequence can no longer stabilize the mutant ensemble, leading to loss of genetic information and potentially viral extinction—a transition that forms the basis of an antiviral strategy termed lethal mutagenesis [14] [15].

In a simplified two-population model (wild-type and average mutant), the error threshold occurs when mutation rate overcomes the critical value:

Where (f0) is the fitness of the wild-type sequence and (f1) is the fitness of the average mutant [16]. This relationship highlights the delicate balance between mutation rates that generate diversity and those that destroy inheritable genetic information.

Quasispecies theory also introduces the concept of sequence space—a multidimensional discrete space where each node corresponds to a genotype connected to neighboring genotypes by single-point mutations [16]. For an RNA virus, the sequence space is astronomically large (4^L for a genome of length L), and the distribution of fitness values across this space constitutes the fitness landscape that guides evolutionary trajectories [16].

Fitness Landscapes and Evolutionary Dynamics

Fitness landscapes represent a conceptual model where each genotype is associated with a quantitative fitness value [16]. These landscapes range from smooth surfaces with single peaks to rugged terrains with multiple adaptive solutions. For RNA viruses, fitness landscapes are increasingly viewed as very rugged and dynamic, reflecting the complex interactions between viral genotypes and host environments [16].

The quasispecies structure leads to unique evolutionary phenomena such as "survival of the flattest"—where a quasispecies located at a low but evolutionarily neutral and highly connected region in the fitness landscape can outcompete a quasispecies located at a higher but narrower fitness peak [15]. This occurs because the former population possesses greater robustness to mutation, maintaining functionality across a wider range of genetic variants.

Methodologies for Quasispecies Characterization

Next-Generation Sequencing Approaches

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized quasispecies characterization by enabling detection of variants at frequencies as low as 1% in the quasispecies pool [17]. The massive sequencing depth provided by NGS platforms allows unprecedented resolution of mutant spectra, revealing the complex genetic architecture of viral populations.

Key NGS applications in quasispecies research include:

- Ultra-deep sequencing of viral genomes to characterize minority variants

- Haplotype reconstruction to determine linked mutations across genomes

- Longitudinal tracking of quasispecies evolution during infection and treatment

- Identification of adaptive mutations under selective pressures

Computational Assembly and Analysis Tools

The genetic diversity and high mutation rates of viral quasispecies present significant challenges for genome assembly. Specialized computational tools have been developed to address these challenges:

Table 1: Computational Tools for Viral Quasispecies Analysis

| Tool | Methodology | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAVAGE [18] | Overlap graph-based assembly | De novo haplotype reconstruction | Reference-free assembly; deep coverage data (>20,000×) |

| FC-Virus [19] | Homologous k-mer backbone | Full-length consensus assembly | Identifies k-mers shared across strains; builds single consensus |

| QAP [17] | Operational taxonomic unit analysis | Quasispecies quantification | Automated processing of NGS data; machine learning integration |

| VICUNA [18] | Overlap-layout-consensus | Consensus assembly from ultra-deep sequencing | Designed for highly diverse viral populations |

| HaploClique [18] | Maximal clique enumeration | Haplotype resolution | Reference-guided overlap graph approach |

Experimental Protocol: NGS-Based Quasispecies Analysis

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for characterizing viral quasispecies using next-generation sequencing:

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

- Extract viral RNA/DNA from patient serum or cell culture samples

- Amplify target regions using reverse transcription-PCR with overlapping primers

- For whole-genome analysis, amplify multiple overlapping fragments covering the entire viral genome

- Quantify amplification products and normalize concentrations

- Prepare sequencing libraries using platform-specific kits (e.g., Nextera DNA Sample Prep Kit for Illumina)

- Perform size selection to remove fragments <400 bp using AMPure XP beads

- Validate library quality using an Agilent Bioanalyzer

- Quantify libraries by real-time PCR prior to sequencing

Sequencing and Data Processing

- Sequence amplified fragments using an Illumina MiSeq platform (2 × 300 bp paired-end protocol)

- Perform image analysis and base calling using platform-specific software (e.g., CASAVA for Illumina)

- Quality filter raw sequencing data: remove adapters, discard reads <250 bp, and eliminate low-quality sequences (base quality <25)

- Map clean reads to reference genomes using appropriate mapping algorithms

- Assemble read pairs into amplicon sequences based on mapping positions

- Correct sequencing errors and generate viral haplotypes

Quasispecies Quantification and Analysis

- Define viral operational taxonomic units (OTUs) based on genetic distances

- Perform hierarchical clustering analysis to identify quasispecies patterns

- Conduct principal component analysis to visualize population structures

- Apply machine learning algorithms for phenotype classification (e.g., K-nearest neighbor, support vector machine, random forest)

- Correlate quasispecies features with clinical and virological parameters

Quantitative Analysis of Quasispecies Diversity

Mutation Rates and Population Genetics

Viral quasispecies are characterized by exceptionally high mutation rates that drive their genetic diversity. RNA viruses exhibit mutation rates ranging from 10^-6 to 10^-4 mutations per nucleotide per cellular infection, while DNA viruses typically range from 10^-8 to 10^-6 [20]. These rates are several orders of magnitude higher than those of cellular organisms, facilitating rapid generation of genetic diversity.

The population genetics of viral quasispecies are influenced by the interplay of mutation supply, genetic drift, and selection. The total mutation supply depends on both the mutation rate per sequence (μ) and the effective population size (Ne), captured in the population mutation rate θ = 4Neμ [20]. Viral populations typically experience stronger genetic drift than other organisms with similar census population sizes due to fluctuating population sizes and skewed offspring distributions.

Clinical Correlations and Quantitative Assessments

Advanced quasispecies analysis has revealed significant correlations between viral diversity and clinical outcomes. In a study of 290 HBeAg-positive patients, quasispecies analysis based on NGS data demonstrated distinct clustering between immune tolerant (IT) and chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients [17]. Machine learning models incorporating quasispecies features showed higher diagnostic accuracy for IT phase classification compared to conventional markers like HBsAg titer, APRI, and FIB-4 scores.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters in Viral Quasispecies Research

| Parameter | Description | Measurement Approach | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | Rate of nucleotide changes per replication cycle | Clonal sequencing, fluctuation tests | Determines evolutionary potential; typically 10^-6 to 10^-4 for RNA viruses |

| Mutation Frequency | Average number of mutations per genome relative to consensus | NGS with error correction | Indicator of population diversity; ~1-2 mutations/genome in Qβ phage |

| Shannon Entropy | Measure of quasispecies complexity | NGS variant frequency distribution | Higher values indicate greater diversity within population |

| Hamming Distance | Number of positional differences between sequences | Pairwise sequence comparison | Quantifies genetic divergence within quasispecies |

| Error Threshold | Maximum mutation rate compatible with genetic stability | Theoretical calculation, mutagenesis experiments | μc = 1 - f1/f_0 in simple model; basis for lethal mutagenesis |

Biological Implications and Clinical Relevance

Pathogenesis and Immune Evasion

The quasispecies nature of viruses has profound implications for pathogenesis and immune evasion. The continuous generation of variant genomes provides a reservoir for immune escape mutants that can evade host neutralizing antibodies and cytotoxic T-cell responses [16] [14]. This dynamic is particularly evident in chronic infections such as those caused by HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus, where quasispecies evolution facilitates persistence in the face of sustained immune pressure [14] [15].

Studies of hepatitis B virus (HBV) have revealed that quasispecies complexity within the basal core promoter/precore/core region correlates with liver inflammation and fibrosis severity [17]. The relative abundance of specific viral OTUs differs significantly between immune tolerant and chronic hepatitis B patients, suggesting that quasispecies composition reflects host-virus interactions and disease progression.

Drug Resistance and Antiviral Therapy

Quasispecies dynamics present major challenges for antiviral therapy through several mechanisms:

- Pre-existence of resistant variants within mutant spectra before treatment initiation

- Rapid selection of resistant mutants under drug pressure

- Compensatory mutations that restore fitness to resistant variants

- Collective behavior of mutant spectra that can suppress or enhance specific variants

The high evolutionary potential of viral quasispecies necessitates combination therapies targeting multiple viral functions simultaneously [12]. This approach reduces the probability of selecting resistant mutants by requiring multiple concurrent mutations for escape. Additionally, the error threshold concept has inspired therapeutic strategies based on lethal mutagenesis, where mutagenic agents are used to increase viral mutation rates beyond sustainable levels [14] [12].

Intra-population Interactions and Collective Behavior

A crucial aspect of quasispecies dynamics is the presence of interactions among components of mutant spectra. These include:

- Complementation: Cooperative interactions where genomes encode products that mutually assist replication

- Interference: Negative interactions where some genomes suppress replication of others

- Defector phenomena: Mutants that exploit resources without contributing to population fitness

Experimental evidence demonstrates that the complete mutant ensemble often exhibits replicative advantages over its individual components [12]. This collective behavior underscores that viral quasispecies can act as units of selection, with properties that transcend those of their constituent variants.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Quasispecies Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp UltraSens Virus Kit | Viral RNA/DNA extraction from clinical samples | Maximize yield from low-volume samples; prevent contamination |

| Amplification Primers | HBV fragment P5 primers (BCP/precore/core) | Target-specific amplification for NGS | Design overlapping amplicons for genome coverage |

| Library Preparation Kits | Nextera DNA Sample Prep Kit | NGS library construction from PCR products | Fragment size selection critical for quality libraries |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq | High-depth sequencing of viral populations | 2 × 300 bp paired-end provides length and accuracy balance |

| Computational Tools | SAVAGE, FC-Virus, QAP | Data analysis, assembly, and quantification | Choose based on reference availability and research goals |

| Quality Control Tools | Agilent Bioanalyzer, AMPure XP beads | Library validation and size selection | Essential for removing primer dimers and short fragments |

Viral quasispecies represent a fundamental evolutionary strategy that enables RNA viruses and some DNA viruses to maintain adaptability in changing environments. The theoretical framework developed by Eigen and Schuster, combined with modern experimental approaches, has transformed our understanding of viral populations as dynamic mutant ensembles rather than static entities. The application of next-generation sequencing technologies and sophisticated computational tools has provided unprecedented insights into quasispecies dynamics, revealing their critical roles in pathogenesis, immune evasion, and drug resistance.

Ongoing research continues to elucidate the complex interactions within mutant spectra and their collective behavior as units of selection. These advances hold promise for novel therapeutic strategies that leverage quasispecies principles, such as lethal mutagenesis and combination therapies that exploit evolutionary constraints. As our understanding of viral quasispecies deepens, so too does our capacity to develop more effective interventions against rapidly evolving viral pathogens.

Apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) enzymes are host-encoded cytidine deaminases that function as a frontline defense mechanism against viral pathogens by introducing mutations into viral genomes. While their role in restricting viruses such as HIV-1 is well-established, recent evidence indicates that these enzymes also serve as powerful drivers of viral genetic diversity, influencing evolutionary trajectories, immune evasion, and therapy resistance. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the mechanisms by which APOBEC-mediated hypermutation occurs, summarizes quantitative data on mutation signatures across different viruses, details key experimental methodologies for studying these phenomena, and discusses the implications for viral evolution and therapeutic intervention within the broader context of viral genetic diversity research.

The APOBEC family of zinc-dependent cytidine deaminases represents a crucial component of the innate immune system, providing an intracellular defense mechanism against exogenous viruses and endogenous retroelements [21] [22]. In humans, the APOBEC3 (A3) subfamily has expanded to include seven members (A3A, A3B, A3C, A3D, A3F, A3G, and A3H) that serve as potent restriction factors against diverse viral pathogens [23] [24]. These enzymes catalyze the deamination of cytosine to uracil (C-to-U) in single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) intermediates generated during viral replication, leading to genomic strand guanine-to-adenine (G-to-A) hypermutation in subsequent replication cycles [21] [22]. This mutagenic capability can be profoundly lethal to viruses, with certain A3 enzymes capable of deaminating up to 10% of viral cDNA cytosines in a single replication round, effectively destroying viral infectivity [21].

Beyond their direct antiviral restriction function, APOBEC enzymes have emerged as significant drivers of viral evolution. Sublethal levels of APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis introduce genetic diversity that can be subject to natural selection, potentially yielding viral variants with enhanced fitness, including those capable of immune evasion and drug resistance [23] [24]. The COVID-19 pandemic has provided striking evidence for this phenomenon, with analyses of SARS-CoV-2 genomes revealing that more than 65% of recorded mutations are attributable to interactions with APOBECs and adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADAR) [23]. This dual nature—both restraining and shaping viral populations—establishes APOBEC enzymes as critical determinants in host-virus evolutionary dynamics.

Biochemical Mechanisms of APOBEC-Mediated Hypermutation

Structural Basis and Deamination Mechanism

APOBEC enzymes share a conserved structural architecture centered on a zinc-coordinating active site. The catalytic domain contains a consensus zinc-binding motif with the sequence His-X-Glu-X23–28-Pro-Cys-X2–4-Cys (where X represents any amino acid), where the histidine and cysteine residues coordinate a zinc ion essential for catalytic activity [21] [24]. The proposed deamination mechanism, derived from structural studies of bacterial and yeast cytidine deaminases, involves a zinc-mediated hydrolytic attack on the cytosine base:

- A conserved glutamic acid residue deprotonates a water molecule, generating a zinc-stabilized hydroxide ion [21] [24].

- This hydroxide ion attacks the 4-position of the cytosine pyrimidine ring, leading to the formation of an unstable tetrahedral intermediate [21].

- The reaction proceeds with the elimination of ammonia (NH3), resulting in a uracil base [21] [22].

The structural basis for substrate specificity has been elucidated through co-crystal structures of A3A and A3B C-terminal domain bound to ssDNA. These structures reveal that the DNA substrate adopts a U-shaped conformation, with the target cytosine flipped out and inserted deep into the zinc-coordinating active site pocket, while the -1 nucleotide (immediately 5' to the target cytosine) is also flipped out and makes specific hydrogen-bonding contacts with the protein that determine sequence preference [21].

Figure 1: APOBEC Deamination Mechanism. The diagram illustrates the stepwise process of cytosine-to-uracil deamination catalyzed by APOBEC enzymes, involving zinc-mediated hydrolysis.

A critical feature of APOBEC enzymes is their distinct preference for specific dinucleotide contexts, which creates recognizable mutational signatures in viral genomes:

- A3G uniquely prefers target cytosines preceded by another cytosine (5′-CC → 5′-CU) [21] [22] [24].

- A3A, A3B, A3C, A3D, A3F, and A3H prefer target cytosines preceded by a thymine (5′-TC → 5′-TU) [21] [22].

Additional flanking sequences (the -2 and +1 positions) also influence deamination efficiency, though these preferences are less strictly defined [21]. The structural basis for the TC/CC preference lies in specific interactions between the enzyme and the flipped-out -1 base (T for A3A-A3H, C for A3G) [21]. This specificity allows researchers to infer which APOBEC enzyme is responsible for observed mutation patterns in viral sequences.

Table 1: APOBEC Enzyme Characteristics and Mutation Signatures

| APOBEC Enzyme | Domain Organization | Preferred Motif | Primary Viral Targets | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3A | Z1 | 5′-TC | SARS-CoV-2, HBV | Nucleus/Cytoplasm |

| A3B | Z2-Z1 | 5′-TC | HIV-1, HBV | Nucleus |

| A3C | Z2 | 5′-TC | HIV-1, HBV | Nucleus/Cytoplasm |

| A3D | Z2-Z2 | 5′-TC | HIV-1 | Cytoplasm |

| A3F | Z2-Z2 | 5′-TC | HIV-1 | Cytoplasm |

| A3G | Z2-Z1 | 5′-CC | HIV-1, HTLV-1 | Cytoplasm |

| A3H | Z3 | 5′-TC | HIV-1, HBV | Haplotype-dependent |

APOBEC-Mediated Hypermutation Across Different Virus Families

Retroviruses: HIV-1 as the Prototype

The interaction between APOBEC3 enzymes and HIV-1 represents the most extensively characterized model of APOBEC-mediated viral restriction. The established mechanism involves:

- Packaging: A3D, A3F, A3G, and A3H incorporate into budding HIV-1 virions through interactions between their N-terminal domains and viral genomic RNA [21].

- Reverse Transcription: During reverse transcription in the newly infected cell, the viral RNA genome is reverse-transcribed into ssDNA, which serves as a substrate for APOBEC enzymes.

- Deamination: APOBEC enzymes deaminate cytosines to uracils in the nascent minus-strand viral DNA [21] [22].

- Fixed Mutations: During plus-strand synthesis, the uracils template adenines, resulting in G-to-A hypermutation in the genomic strand [21] [25].

HIV-1 has evolved a sophisticated countermeasure in the form of the Viral Infectivity Factor (Vif) protein, which acts as a substrate receptor for a CUL5 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that targets multiple A3 enzymes for proteasomal degradation [21] [24]. In Vif-deficient HIV-1, A3 enzymes can introduce lethal levels of mutation, but in Vif-proficient viruses, sublethal mutagenesis may occur, potentially driving viral evolution and the emergence of variants with altered phenotypes [23] [24].

Figure 2: APOBEC3 Restriction of HIV-1 and Vif Counteraction. The diagram contrasts viral outcomes in the presence and absence of the HIV-1 Vif protein, which targets APOBEC3 proteins for degradation.

DNA Viruses and RNA Viruses

APOBEC enzymes demonstrate activity against a broad spectrum of viruses beyond retroviruses:

- Hepatitis B Virus (HBV): A3A hypermutates a small proportion (~10⁻²) of HBV genomes extensively, with up to 40% of cytosines converted to uracils in the hypermutated genomes [25] [26]. The overall hypermutation frequency is low, but the mutations are extensive in the affected genomes.

- SARS-CoV-2: Recent evidence demonstrates that A3A, A1 (with cofactor A1CF), and A3G can edit specific sites on SARS-CoV-2 RNA, producing C-to-U mutations [27]. Surprisingly, rather than inhibiting viral replication, APOBEC3 expression promoted viral replication and propagation in Caco-2 cells, suggesting SARS-CoV-2 may exploit APOBEC-mediated mutations for fitness and evolution [27]. Database analyses indicate that C-to-U mutations account for approximately 40% of all single nucleotide variations in SARS-CoV-2 sequences [27].

Table 2: Hypermutation Patterns Across Different Viruses

| Virus | Genome Type | APOBEC Enzymes Involved | Hypermutation Frequency | Mutation Load in Hypermutated Genomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | Retrovirus | A3D, A3F, A3G, A3H | Up to 43% (env DNA) | Up to 50% of guanines mutated |

| HTLV-1 | Retrovirus | A3G | Low (10⁻²–10⁻⁴) | Extensive in affected proportion |

| HBV | DNA virus | A3A | <2–35% (varies by method) | 20-40% of cytosines mutated |

| SARS-CoV-2 | RNA virus | A3A, A1, A3G | Not quantified | Specific UC/AC motif editing |

Quantitative Analysis of APOBEC-Mediated Mutations

The extent and impact of APOBEC-mediated hypermutation vary significantly across virus families and experimental systems. Key quantitative observations include:

- HIV-1: Massive parallel sequencing of HIV-1 env DNA revealed that G-to-A hypermutations varied from <1% to 85% depending on the genomic site, with a hypermutation level of 75.2 ± 9.1% observed at hotspot 7424 among sequences with GG-to-AG mutations [25] [26]. Overall, 43.1 ± 5.2% of HIV-1 env DNA sequences showed evidence of hypermutation by endogenous APOBEC3 proteins [26].

- HBV: Studies using differential DNA denaturation PCR (3D-PCR) estimated that only ~10⁻² HBV genomes in the total population were hypermutated by A3A, but in these hypermutated genomes, an average of 20.5% and 40.1% of cytosines on the minus and plus strands, respectively, were mutated in the evaluated region [25] [26].

- Experimental Systems: In cell-free systems, hypermutation induced by purified A3G is proportional to enzyme concentration in a dose-dependent manner [25] [26]. This contrasts with the situation in cells, where extensive hypermutation occurs only in a small proportion of viral genomes, suggesting the involvement of cellular regulatory factors [25] [26].

Table 3: Experimental Methods for Detecting APOBEC Hypermutation

| Method | Principle | Applications | Sensitivity | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-PCR | Exploits lower denaturation temperature of AT-rich hypermutated DNA | HIV-1, HBV, HTLV-1, MLV | Can detect 1 hypermutant in 10⁴ wild-type | Enriches rare hypermutated genomes; no specialized equipment | Semi-quantitative; requires optimization of denaturation temperature |

| Safe Sequencing System (SSS) | Uses unique molecular barcodes to eliminate PCR and sequencing errors | SARS-CoV-2 RNA editing studies | Can distinguish true mutations with frequency <0.1% | Extremely high accuracy; quantitative | Expensive; technically demanding; limited coverage |

| Deep Sequencing with Bioinformatics | High-throughput sequencing followed by motif analysis | HIV-1, cancer genomes | Depends on sequencing depth | Genome-wide analysis; can attribute to specific APOBECs | Requires sophisticated bioinformatics; may miss rare hypermutants |

| Massive Parallel Sequencing | Clonal sequencing of specific genomic regions | HIV-1 env hypermutation | Quantitative across population | Provides quantitative frequency data | Targeted approach; may miss genome-wide patterns |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Detecting Hypermutation Using 3D-PCR

Differential DNA Denaturation PCR (3D-PCR) is a well-established method for enriching and detecting hypermutated viral genomes based on their reduced thermodynamic stability due to increased AT content resulting from C-to-U mutations [25] [26].

Protocol:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total DNA or RNA from infected cells or viral particles. For RNA viruses, perform reverse transcription using a high-fidelity reverse transcriptase.

- Primary PCR Amplification: Amplify the target viral genomic region of interest using standard PCR conditions with gene-specific primers.

- 3D-PCR Amplification:

- Prepare identical PCR reactions with the primary PCR product as template.

- Perform parallel amplifications across a gradient of denaturation temperatures (typically ranging from 78°C to 88°C in 0.5-1°C increments).

- The optimal denaturation temperature for enriching hypermutated sequences must be determined empirically for each target.

- Analysis:

- Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Hypermutated sequences will be preferentially amplified at lower denaturation temperatures.

- Clone and sequence products from different temperature fractions to confirm the presence of G-to-A (for plus-strand) or C-to-T (for minus-strand) mutations in the appropriate APOBEC context (TC or CC motifs).

Technical Considerations:

- The method is particularly useful for detecting low-frequency hypermutation events (as low as 10⁻⁴) [25].

- Proper controls are essential, including samples known to be non-hypermutated.

- The technique has been successfully applied to HIV-1, HTLV-1, HBV, and MLV [25] [26].

Safe Sequencing System (SSS) for RNA Editing Detection

The Safe Sequencing System (SSS) is a targeted next-generation sequencing approach that minimizes errors to accurately detect rare mutations, such as those introduced by APOBEC-mediated RNA editing [27].

Protocol:

- Reporter Construct Design:

- Clone target viral RNA segments (e.g., 200 nt segments from SARS-CoV-2 genome) into a DNA reporter vector downstream of an eGFP coding sequence.

- Include an AAV intron within eGFP to enable differentiation between mature mRNA and genomic DNA.

- Cell-Based Editing Assay:

- Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the reporter vector and APOBEC expression vectors (e.g., A3A, A1+A1CF, A3G).

- Include empty vector controls for background mutation rate determination.

- RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription:

- Extract total RNA 48 hours post-transfection.

- Perform reverse transcription using a high-fidelity reverse transcriptase (e.g., AccuScript) with a primer annealing to the exon-exon junction to specifically amplify mature mRNA.

- UID Library Preparation:

- Perform 2 cycles of initial PCR amplification using primers containing a 15 nt Unique IDentifier (UID) barcode to tag each original RNA molecule.

- Purify the initial PCR products.

- Amplify with Illumina adaptors for sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Group sequencing reads by UID to create consensus sequences for each original molecule.

- Eliminate random mutations that are not present in all reads of a UID family.

- Calculate editing efficiency at each cytosine by comparing to control samples.

Technical Considerations:

- SSS effectively overcomes the high error rate of standard NGS sequencing (~10⁻²–10⁻³) [27].

- The method is expensive, typically limiting analysis to specific genomic regions rather than entire viral genomes.

- The approach confirmed that A1+A1CF and A3A exhibit higher RNA editing activity on SARS-CoV-2 segments than A3G [27].

Figure 3: Safe Sequencing System Workflow. The diagram outlines the experimental pipeline for detecting APOBEC-mediated RNA editing with high accuracy using unique molecular barcodes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for APOBEC-Virus Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | APOBEC3A, A3B, A3C, A3D, A3F, A3G, A3H expression plasmids | Gain-of-function studies; mechanistic analysis | HIV-1, HBV, SARS-CoV-2 restriction assays |

| Cell Lines | HEK293T, HepG2, Caco-2, THP-1, Primary CD14+ cells | Model systems for viral infection and APOBEC expression | Cell-based editing and restriction assays |

| Detection Kits | 3D-PCR reagents; Safe Sequencing System components | Detection and quantification of hypermutated genomes | HIV-1, HBV, SARS-CoV-2 mutation analysis |

| Antibodies | Anti-APOBEC3G; Anti-Vif; Anti-HA tag (for tagged proteins) | Immunoblotting; immunoprecipitation; cellular localization | Protein expression and interaction studies |

| Viral Systems | Vif-deficient HIV-1; HBV replication competent clones; SARS-CoV-2 replicons | Models for APOBEC restriction and hypermutation | Antiviral activity assays; evolution studies |

| Inhibitors/Activators | RNase A (disrupts HMM RNPs); Proteasome inhibitors (MG132) | Manipulate APOBEC activity and stability | Mechanistic studies of regulation |

Implications for Viral Evolution and Therapeutic Applications

Driving Viral Evolution

APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis represents a double-edged sword in host-virus interactions. While lethal levels of mutation effectively restrict viral replication, sublethal mutagenesis provides a source of genetic diversity that can drive viral evolution:

- Immune Evasion: APOBEC-induced mutations can generate viral variants capable of escaping host immune responses [23] [24].

- Drug Resistance: Application of Vif inhibitors in HIV-1 therapy has led to the selection of viral variants that are more efficient at replication in the presence of human A3G [23].

- Viral Fitness: In the case of SARS-CoV-2, APOBEC3 expression appears to promote viral replication and propagation, suggesting that some viruses may exploit APOBEC-mediated mutations for fitness gains [27].

The interplay between APOBEC enzymes and viral antagonists creates a molecular "arms race" that shapes viral evolution. Viruses that develop more effective countermeasures against APOBEC restriction (like HIV-1 Vif) gain a selective advantage, while hosts may evolve new APOBEC variants to counter these viral adaptations [23].

Therapeutic Opportunities

The detailed understanding of APOBEC-virus interactions has revealed several promising therapeutic avenues:

- APOBEC Enhancement Strategies: Developing small molecules that enhance APOBEC activity or stability could potentiate their innate antiviral effects. This approach might be particularly effective against viruses lacking robust APOBEC countermeasures.

- Vif Inhibitors: For HIV-1, disrupting the Vif-A3G interaction represents a promising therapeutic strategy. Compounds that prevent Vif-mediated degradation of A3G could restore the cell's innate antiviral defense [21] [24].

- APOBEC Inhibitors in Cancer: Although beyond the scope of viral therapy, APOBEC enzymes (particularly A3A and A3B) are major sources of mutation in cancer genomes [21]. Inhibitors developed for cancer applications might also be useful for controlling APOBEC-mediated viral evolution in chronic infections.

The dual role of APOBEC enzymes—as both restriction factors and mutators driving evolution—underscores the complexity of targeting these enzymes for therapeutic purposes. A nuanced approach that considers the specific virus, infection context, and potential evolutionary consequences will be essential for successful therapeutic development.

APOBEC enzymes represent a powerful innate defense mechanism that directly mutates viral genomes through site-specific cytidine deamination. While their restriction function provides crucial protection against diverse viral pathogens, their mutagenic capacity also serves as a significant driver of viral evolution, contributing to immune evasion, drug resistance, and viral fitness. The experimental approaches detailed in this whitepaper—from 3D-PCR to Safe Sequencing Systems—provide researchers with robust methodologies for investigating APOBEC-mediated hypermutation across different viral systems. As research in this field advances, a more complete understanding of how APOBEC enzymes shape viral genetic diversity will inform the development of novel antiviral strategies and enhance our ability to predict and manage viral evolution in the context of both emerging infections and persistent viral diseases.

A paradigm shift is occurring in our understanding of RNA virus evolution, revealing that arthropods harbor an unprecedented diversity of negative-sense RNA viruses that represent the ancestral roots of major pathogen groups. Through advanced meta-transcriptomic approaches, researchers have discovered that arthropods contain viruses falling basal to vertebrate-specific arenaviruses, filoviruses, hantaviruses, influenza viruses, lyssaviruses, and paramyxoviruses [28]. This technical guide examines the genomic diversity, evolutionary relationships, and experimental methodologies underpinning this discovery, providing researchers with comprehensive protocols and analytical frameworks for investigating the arthropod virosphere. The findings demonstrate that arthropods serve as central reservoirs in viral evolution and highlight the potential for discovering novel viral lineages through systematic surveillance.

Negative-sense RNA viruses (NSVs) constitute major pathogens causing influenza, hemorrhagic fevers, encephalitis, and rabies in humans and livestock [28]. Taxonomically, these viruses encompass at least eight families and four unassigned genera, characterized by an encapsidated negative-sense RNA genome, inverted complementary genome ends, and a homologous RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [28]. Despite their medical importance, the origins and evolutionary history of NSVs remained largely obscure until recent systematic surveys of arthropod viruses.

Arthropods represent the most diverse and abundant group of animals on Earth, yet their viromes have been historically underexplored, with previous studies focusing predominantly on arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) affecting human health [28] [29]. This bias has created significant gaps in understanding viral diversity and evolution. The application of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies has revolutionized virus discovery, enabling researchers to identify novel viral lineages without prior knowledge of sequence information [30]. These approaches have revealed that arthropods harbor a remarkable array of NSVs, including ancestral forms of viruses that cause significant disease in vertebrates [28] [31].

The evolutionary significance of arthropods as viral reservoirs extends beyond mere diversity. Studies demonstrate that many arthropod viruses appear ancestral to vertebrate-infecting viruses, suggesting that arthropods have played a central role in viral evolution over geological timescales [28] [29]. This discovery has profound implications for understanding viral origins, host adaptation, and the emergence of pathogenic viruses. Furthermore, the genomic structures found in arthropod NSVs exhibit remarkable variation, including segmented, unsegmented, and circular forms, providing new insights into the evolution of viral genome organization [28].

Genomic Diversity and Evolutionary Relationships

Extent of Viral Diversity in Arthropods

Comprehensive surveys of arthropod species have revealed an extraordinary diversity of negative-sense RNA viruses, far exceeding previous estimates. A landmark study analyzing 70 arthropod species from four classes (Insecta, Arachnida, Chilopoda, and Malacostraca) discovered 112 novel viruses, providing evidence for at least 16 potentially new families and genera of NSVs [28]. These viruses were defined by their RdRp sequences sharing less than 25% amino acid identity with existing taxa, with the most divergent sequences showing as little as 15.8% amino acid identity to their closest relatives [28].

The scale of this diversity becomes evident when examining broader taxonomic sampling. A subsequent study analyzing 1,243 species across all insect orders and outgroups identified 488 viral RdRp sequences with similarity to negative-sense RNA viruses [29]. These were detected in 324 arthropod species, with coding-complete or nearly-complete genomes obtained in 61 cases [29]. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that these sequences showed similarity to viruses classified in Bunyavirales (n = 86), Articulavirales (n = 54), and several orders within Haploviricotina (n = 94) [29]. Based on phylogenetic topology and available coding-complete genomes, researchers estimate that at least 20 novel viral genera in seven families need to be defined, with only two being monospecific [29].

Table 1: Novel Negative-Sense RNA Viruses Discovered in Arthropod Studies

| Host Group | Number of Species Surveyed | Novel Viruses Identified | Proposed New Taxa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed arthropods (4 classes) | 70 | 112 | 16+ potential families/genera | [28] |

| Hexapoda (comprehensive) | 1,243 | 488 RdRp sequences | 20+ novel genera, 7 families | [29] |

| Aedes aegypti mosquitoes | 96 populations | Multiple ISVs (CFAV, AeAV, PCLV) | - | [32] |

Evolutionary Connections to Vertebrate Viruses

Phylogenetic analyses demonstrate that arthropods harbor viruses that fall basal to major vertebrate virus groups, indicating ancestral relationships. Arthropod viruses have been identified that are ancestral to vertebrate-specific arenaviruses, filoviruses, hantaviruses, influenza viruses, lyssaviruses, and paramyxoviruses [28]. This discovery suggests that arthropods have been central to the evolutionary history of these important pathogen groups.

The evolutionary patterns observed in these viruses provide evidence for both virus-host co-divergence and cross-species transmission. Despite frequent cross-species transmission events, the RNA viruses in vertebrates generally follow the evolutionary history of their hosts [31]. This pattern is particularly evident in flaviviruses, which demonstrate host-specific nucleotide motif usage, with vertebrate-infecting viruses possessing under-representation of CpG and TpA, and insect-only viruses displaying only TpA under-representation [33]. This mimicking of host nucleotide patterns suggests long-term evolutionary associations and host-induced pressures shaping viral genome composition.

Table 2: Arthropod Viruses with Evolutionary Links to Vertebrate Pathogens

| Arthropod Virus Group | Related Vertebrate Virus Family | Evolutionary Relationship | Key Genomic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chuviruses | Arenaviruses, Filoviruses | Basal position in phylogenies | Circular genome forms |

| Insect rhabdoviruses | Lyssaviruses (rabies) | Ancestral lineages | Shared RdRp motifs |

| Arthropod-borne flaviviruses | Vertebrate flaviviruses (dengue, Zika) | Common ancestry with host-specific adaptations | CpG under-representation in vertebrate variants |

| Arthropod influenza-like viruses | Orthomyxoviridae (influenza) | Deep evolutionary roots | Segmented genomes |

Genome Structure Diversity

Arthropod NSVs display remarkable diversity in genome organization and structure, providing insights into the evolution of viral genomes. The spectrum of genome structures includes non-segmented, segmented, and circular forms [28]. This variation in genome architecture is more extensive than that observed in vertebrate viruses, suggesting that arthropods maintain a greater diversity of genomic solutions [28] [31].

The number of genome segments varies considerably among arthropod NSVs, from one (order Mononegavirales; unsegmented) to two (family Arenaviridae), three (Bunyaviridae), three-to-four (Ophioviridae), and six-to-eight (Orthomyxoviridae) [28]. This diversity is further complicated by differences in the number, structure, and arrangement of encoded genes. Notably, some arthropod viruses, such as those in the Chuvirus family, exhibit circular genome forms, which had not been previously documented in NSVs [28]. The discovery of this genomic diversity in arthropods sheds new light on the evolution of genome organization and suggests that arthropods serve as natural laboratories for viral genomic innovation.

Methodological Approaches for Virus Discovery

Sample Collection and Preparation

Comprehensive virus discovery begins with strategic sample collection and processing. In the seminal study by Li et al., researchers collected 70 arthropod species representing four classes (Insecta, Arachnida, Chilopoda, and Malacostraca) from various locations in China [28]. Specimens were pooled by taxonomic group, resulting in 16 separate cDNA libraries for sequencing [28]. This approach ensured broad representation across arthropod diversity while maximizing sequencing efficiency.

Nucleic acid extraction methods vary depending on downstream applications. For total RNA sequencing, extraction is typically performed using TRI Reagent protocols, with quality assessment conducted using instruments such as the 2100 Bioanalyzer to record band sizes associated with 18S and 28S rRNA peaks as a measure of RNA integrity [32]. For virome studies focusing on virus discovery, several nucleic acid templates can be utilized: (i) total plant RNA extracts, usually with ribosomal depletion; (ii) virion-associated nucleic acids (VANA) extracted from purified viral particles; (iii) double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) enriched through cellulose chromatography or monoclonal antibody pull-down; and (iv) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [30]. Each approach has distinct advantages and limitations, with total RNA sequencing and siRNA sequencing being most generically applicable to viruses with different genome types and replication strategies [30].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library preparation methodologies are critical for successful virus discovery. In arthropod virus studies, library preparation is typically performed using kits such as the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA LT Sample Prep Kit with rRNA depletion (Ribo-Zero H/M/R Gold) [32]. This ribosomal RNA depletion step is crucial for enriching non-host transcripts, including viral RNAs, thereby improving sequencing depth for viral discovery.

Sequencing is predominantly performed on Illumina platforms, such as the Illumina NovaSeq 6000, generating 100-base pair paired-end reads [32]. The scale of data generation in these studies is substantial, with the Li et al. study producing 147.4 Gb of 100-base pair-end reads from 16 cDNA libraries [28]. This deep sequencing enables detection of low-abundance viral transcripts and facilitates assembly of complete or near-complete viral genomes.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Arthropod Virus Discovery

Bioinformatic Analysis and Virus Identification

Bioinformatic processing of sequencing data follows a structured workflow. Quality control is performed using tools such as FastQC, followed by adapter trimming and removal of low-quality bases using Prinseq-lite or Trimmomatic [32]. To enhance virus detection efficiency, host transcripts are typically filtered by aligning sequences to the host genome (where available) using aligners like Hisat2 [32]. The remaining non-host reads are then subjected to de novo assembly using programs such as Trinity to generate contigs [32].

Viral sequence identification employs similarity-based approaches, with assembled contigs compared against protein sequences of negative-sense RNA viruses using Blastx [28]. Stringent thresholds (E ≤ 1×10^(-6)) are applied to minimize false positives [32]. For the core viral gene used in phylogenetic analysis, the RNA-directed RNA polymerase (RdRp) is typically targeted due to its conservation across all replicating RNA viruses [29]. Profile hidden Markov models (pHMMs) trained on conserved RdRp motifs can enhance detection of divergent viruses [29].

Phylogenetic placement of novel viruses utilizes multiple sequence alignment of RdRp sequences followed by tree reconstruction using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods. These analyses determine the evolutionary relationships between newly discovered viruses and established taxa, revealing ancestral positions and novel lineages [28] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Arthropod Virus Discovery