Viral Genome Organization and Replication Strategies: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive examination of viral genome organization and replication strategies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Viral Genome Organization and Replication Strategies: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of viral genome organization and replication strategies, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental diversity of viral genetic architectures—including DNA vs. RNA, single-stranded vs. double-stranded, and segmented vs. non-segmented genomes—and their direct influence on replication mechanisms. The scope extends to advanced methodologies for studying genome organization, the challenges posed by high mutation rates and host immune responses, and a comparative analysis of replication fidelity and error correction across virus families. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with contemporary research, this review highlights how understanding these viral strategies is pivotal for developing novel antiviral therapeutics and vaccines.

The Architectural Blueprint: Exploring the Diversity of Viral Genome Structures

The fundamental distinction between DNA and RNA genomes defines the molecular architecture, replication dynamics, and evolutionary trajectory of viruses. This technical guide examines the core structural and functional characteristics of viral nucleic acids, framing them within the context of genome organization and replication strategy research. Understanding these principles provides the foundation for developing broad-spectrum antiviral therapeutics and advancing viral vector technologies for gene therapy. The following sections provide a quantitative comparison of genome properties, detailed experimental methodologies for studying replication pathways, and an analysis of host interaction networks that inform drug discovery.

Genomic Architecture and Molecular Composition

Viral genomes exhibit remarkable diversity in nucleic acid structure, configuration, and packaging. The chemical composition of the genetic material—DNA or RNA—directly influences genome stability, replication fidelity, and evolutionary adaptation.

Molecular Structures and Properties

Table 1: Molecular Composition of DNA and RNA Viral Genomes

| Characteristic | DNA Viral Genomes | RNA Viral Genomes |

|---|---|---|

| Sugar Component | Deoxyribose (lacks hydroxyl group at 2' position) [1] | Ribose (contains hydroxyl group at 2' position) [1] |

| Nitrogenous Bases | Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C) [1] | Adenine (A), Uracil (U), Guanine (G), Cytosine (C) [1] |

| Base Pairing | A-T, C-G [2] | A-U, C-G [2] |

| Strandedness | Single-stranded (ssDNA) or double-stranded (dsDNA) [3] | Single-stranded (ssRNA) or double-stranded (dsRNA) [3] |

| Strand Configuration | Linear or circular [4] | Typically linear [4] |

| Chemical Stability | More stable; resistant to alkaline conditions [1] | Less stable; susceptible to hydrolysis in alkaline conditions [1] |

| UV Sensitivity | Vulnerable to UV damage [1] | More resistant to UV damage [1] |

The structural differences between DNA and RNA have profound implications for viral function. DNA's deoxyribose sugar lacks a hydroxyl group at the 2' position, making it more chemically stable than RNA, which contains ribose with a reactive hydroxyl group at the same position [1]. This structural distinction contributes to DNA's superior stability as a genetic storage medium. Additionally, the substitution of thymine in DNA with uracil in RNA represents another key biochemical difference that affects base-pairing interactions and mutation profiles [1].

Genome Size and Organizational Patterns

Table 2: Genome Size and Organization Characteristics

| Parameter | DNA Viruses | RNA Viruses |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Genome Size Range | Several thousand base pairs to over 1 million bp [4] | Few thousand to tens of thousands of bases [4] |

| Genome Segmentation | Typically monopartite (single molecule) [5] | Often multipartite (segmented) [5] |

| Coding Capacity | Larger; encodes more proteins [6] | Smaller; limited coding capacity [6] |

| Gene Overlap | Less common | More common to maximize coding capacity [4] |

| Mutation Rate | ~10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹¹ mutations per nucleotide per cycle [4] | ~10⁻³ to 10⁻⁵ mutations per nucleotide per cycle [4] |

| Evolutionary Rate | Slower evolution | Rapid evolution [5] |

DNA viruses generally possess larger genomes with greater coding capacity, enabling them to encode numerous viral proteins, including immunomodulatory factors that manipulate host defenses [6]. RNA viruses typically have compact genomes with overlapping reading frames and limited coding capacity, often resulting in multifunctional proteins that maximize the utility of their genetic information [4]. The segmentation observed in many RNA viruses (e.g., influenza with 8 segments) facilitates genetic reassortment, contributing to viral diversity and emergence of novel strains [5] [4].

Replication Strategies and Experimental Analysis

Viral replication strategies are fundamentally determined by genome composition, with distinct pathways for DNA and RNA viruses. These strategies involve different polymerase enzymes, replication locales, and host machinery utilization.

DNA Virus Replication Pathways

Most DNA viruses replicate in the nucleus and utilize host cell DNA synthesis machinery, particularly for transcription and genome replication [7] [4]. Notable exceptions include poxviruses, which replicate in the cytoplasm and encode their own DNA-dependent RNA polymerase [7]. The replication process typically follows a conventional pathway: DNA → RNA → protein [4].

Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses first convert their genome to a double-stranded DNA intermediate using host cell DNA polymerases before transcription and replication proceed [7]. The switch from transcription to genome replication is tightly regulated, with early genes encoding regulatory and catalytic proteins expressed before late genes responsible for structural components [7].

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing DNA Virus Replication

Objective: To characterize the replication cycle of double-stranded DNA viruses in host cell nuclei.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Infection: Grow permissive host cells (e.g., Vero or HEK-293) to 70-80% confluence. Infect with DNA virus (e.g., Herpes Simplex Virus) at appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI). Include mock-infected controls.

- Metabolic Labeling: At various post-infection time points (2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours), pulse-label cells with ³²P-orthophosphate or ³H-thymidine to monitor nascent DNA synthesis.

- Nuclear Fractionation: Lyse cells using hypotonic buffer and separate nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions by differential centrifugation.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total DNA using phenol-chloroform method or commercial kits. Treat with DNase-free RNase to remove RNA contamination.

- Southern Blot Analysis: Digest DNA with restriction enzymes, separate by agarose gel electrophoresis, transfer to membrane, and hybridize with virus-specific ³²P-labeled probes.

- Quantitative PCR: Perform qPCR with viral gene-specific primers to quantify genome copy numbers at different infection stages.

- Inhibitor Studies: Apply specific polymerase inhibitors (e.g., acyclovir for herpesviruses) to distinguish viral vs. host replication machinery.

Key Reagents:

- Permissive cell lines

- Viral stocks with determined titer

- ³²P-orthophosphate or ³H-thymidine

- Virus-specific antibodies or probes

- DNA polymerase inhibitors

- Nucleic acid extraction and purification kits

RNA Virus Replication Pathways

RNA viruses employ more diverse replication strategies, largely determined by their sense and strandedness. Most replicate in the cytoplasm using virus-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps) [7] [4]. These RdRps typically lack proofreading capability, contributing to higher mutation rates [7].

Positive-sense RNA viruses can directly translate their genomes as mRNA upon uncoating [7] [5]. Negative-sense RNA viruses must first be transcribed to positive-sense RNA by viral polymerases packaged within the virion [7] [5]. Retroviruses represent a special category that replicates through a DNA intermediate using reverse transcriptase, enabling integration into the host genome [3] [8].

Experimental Protocol: Investigating RNA Virus Replication Complexes

Objective: To isolate and characterize membrane-associated replication complexes from RNA virus-infected cells.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Infection: Culture appropriate host cells and infect with RNA virus (e.g., poliovirus or hepatitis C virus) at optimal MOI.

- Metabolic Labeling: At various post-infection intervals, label with ³H-uridine in the presence of actinomycin D (to inhibit cellular RNA synthesis).

- Membrane Fractionation: Harvest cells and disrupt with Dounce homogenizer. Separate membrane-bound compartments by sucrose density gradient centrifugation.

- Immunofluorescence Microscopy: Fix cells at different time points, permeabilize, and stain with antibodies against viral replication proteins and cellular organelle markers.

- RNA Extraction and Analysis: Extract RNA from membrane fractions and analyze by Northern blotting or RT-PCR with virus-specific primers.

- RdRp Activity Assay: Measure RNA polymerase activity in vitro using isolated membrane fractions with radiolabeled nucleotides.

- Electron Microscopy: Process samples for thin-section EM to visualize replication vesicles and viral particles.

Key Reagents:

- Actinomycin D

- ³H-uridine

- Sucrose gradients

- Antibodies against viral proteins (e.g., NS5A for HCV) and organelle markers

- Radiolabeled nucleotides (α-³²P-UTP)

- RdRp activity assay kit

Structural Organization and Capsid Assembly

The packaging of viral nucleic acids into protective protein shells represents a critical phase in the viral life cycle. The structural organization of these capsids is intimately linked to genome characteristics and follows precise geometric principles.

Capsid Symmetry and Assembly Mechanisms

Most spherical viruses adopt icosahedral symmetry for their capsids, representing "the most efficient way to build a strong container from many identical parts" [9]. This architecture provides maximum protection for the genome with minimal building blocks [9]. The triangulation number (T-number) quantifies capsid complexity, with higher T-numbers corresponding to larger capsids (e.g., T=3 and T=4) [9].

Recent research has revealed that capsid assembly, while appearing chaotic initially with proteins sticking in wrong places, is guided by protein elasticity that allows self-correction through breaking faulty bonds [9]. The viral genome plays an active scaffolding role in this process, attracting protein subunits along its length and raising their local concentration to facilitate proper shell formation [9]. Genome size directly influences capsid dimensions, with the radius of gyration determining the most stable shell size [9].

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Viral Capsid Assembly

Objective: To visualize the assembly pathway of icosahedral viral capsids around nucleic acid cores.

Methodology:

- Component Purification: Express and purify recombinant capsid proteins from E. coli or baculovirus system. Purify viral genomic RNA or DNA.

- In Vitro Assembly: Mix capsid proteins with nucleic acids under appropriate buffer conditions (pH, ionic strength) to initiate assembly.

- Time-Resolved Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (TR-SAXS): Collect scattering data during assembly process to monitor intermediate structures.

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy: Rapidly freeze samples at various time points and image using cryo-EM to visualize assembly intermediates.

- Atomic Force Microscopy: Image assembly process in liquid environment to characterize structural dynamics.

- Computational Simulation: Implement coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations modeling protein subunits and flexible genome (as in Zandi et al., 2025) [9].

- Mutational Analysis: Engineer capsid proteins with altered elasticity or charge distribution and assess assembly efficiency.

Key Reagents:

- Recombinant capsid proteins

- Viral genomic RNA/DNA

- TR-SAXS instrumentation

- Cryo-EM equipment

- Atomic force microscope

- Computational resources for simulation

Host Interactions and Implications for Antiviral Development

Viral nucleic acid composition significantly influences host interaction strategies and susceptibility to antiviral interventions. DNA and RNA viruses have evolved distinct mechanisms to exploit host cellular processes.

Differential Host Interaction Networks

Recent comparative interactomics studies analyzing pathogen-host protein-protein interactions (PPIs) reveal distinct targeting strategies between DNA and RNA viruses [6]. DNA viruses typically target both cellular and metabolic processes simultaneously during infection, leveraging their larger genomes to encode proteins that finely manipulate host cell metabolism [6]. In contrast, RNA viruses preferentially interact with proteins functioning in specific cellular processes, particularly intracellular transport and localization [6].

These interaction patterns reflect evolutionary adaptations: DNA viruses have integrated eukaryotic DNA sequences into their genomes, enabling them to encode proteins with complex functional domains that extensively manipulate host processes [6]. RNA viruses, with their limited coding capacity, have evolved protein-binding motifs that communicate with host cells through more targeted interaction networks [6].

Table 3: Host Interaction Patterns and Therapeutic Targeting

| Aspect | DNA Viruses | RNA Viruses |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cellular Targets | Cellular and metabolic processes [6] | Specific cellular processes, intracellular transport [6] |

| Immune Recognition | cGAS pathway detection [4] | RIG-I-like receptor detection [4] |

| Therapeutic Targets | Viral DNA polymerases, host factors involved in DNA replication | RdRp, reverse transcriptase, host transport proteins |

| Potential Broad-Spectrum Targets | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRPs) [6] | Transporter proteins [6] |

| Resistance Development | Slter due to lower mutation rates | Rapid due to high mutation rates [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Viral Nucleic Acid Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Inhibitors | Acyclovir (DNA pol), Rifampicin (RNA pol), NNRTIs (RT) | Distinguish viral vs. host replication mechanisms [7] |

| Metabolic Labels | ³²P-orthophosphate, ³H-thymidine, ³H-uridine | Track nascent nucleic acid synthesis in infected cells |

| Nucleic Acid Probes | Virus-specific ³²P-labeled DNA/RNA probes | Detect viral genomes in Southern/Northern blot analyses |

| Antibodies | Anti-polymerase, anti-capsid, anti-host factor antibodies | Localize viral and host proteins in infected cells |

| Cellular Fractionation Kits | Nuclear-cytoplasmic separation kits, membrane prep kits | Isolate replication complexes from infected cells |

| Reverse Genetics Systems | Infectious clones, plasmid-based rescue systems | Study specific mutations in viral replication |

| Computational Resources | Molecular dynamics software, phylogenetic analysis tools | Model capsid assembly and viral evolution [9] |

Research Applications and Future Directions

Understanding viral nucleic acid core characteristics enables advancements across multiple research domains, from fundamental virology to applied therapeutic development.

Viral Vectors in Gene Therapy

Retroviruses, particularly those with RNA genomes that reverse transcribe to DNA, have been engineered as delivery vehicles for gene therapy [8]. Recent research on Prototype Foamy Virus (PFV) has revealed that minor modifications to the viral Gag protein can alter both the timing of viral integration into host chromatin and the specific genomic integration sites [8]. Wild-type PFV integrates into gene-rich, early-replicating regions, while mutants with altered Gag proteins shift integration to gene-poor, late-replicating regions [8].

This tunable integration system presents significant implications for designing safer viral vectors for gene therapy, potentially allowing engineers to direct therapeutic genes to safer genomic locations [8]. Similar integration pattern shifts have been observed in HIV-1 capsid mutants, suggesting conserved mechanisms across retroviruses that could be exploited for vector optimization [8].

Antiviral Drug Development

The distinct replication strategies and host interaction patterns of DNA and RNA viruses present unique targets for antiviral development. RNA viruses' high mutation rates and error-prone replication make them particularly challenging targets, as they rapidly develop resistance to conventional therapeutics targeting viral proteins [6]. This has prompted increased interest in host-oriented drug targets that act on cellular functions essential for viral replication [6].

The identification of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRPs) and transporter proteins as common targets across viral families suggests promising avenues for broad-spectrum antiviral development [6]. Similarly, understanding capsid assembly intermediates and their vulnerability to disruption offers potential intervention points that could prevent virion formation [9].

The dichotomy between DNA and RNA viral genomes represents a fundamental organizing principle in virology with profound implications for viral replication, evolution, and host interaction strategies. DNA viruses prioritize genomic stability through sophisticated proofreading mechanisms and nuclear replication, while RNA viruses embrace mutational diversity through error-prone replication in the cytoplasm. These distinct evolutionary strategies have shaped specialized approaches to host manipulation, immune evasion, and transmission. Future research elucidating the physical principles of genome packaging, host factor recruitment, and replication complex formation will continue to inform novel therapeutic interventions against existing and emerging viral threats. The ongoing characterization of viral nucleic acid cores remains essential for advancing both fundamental virology and applied medical countermeasures.

The structural configuration of viral genomes—whether single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds)—is a fundamental determinant of replication strategy, host interaction, and evolutionary trajectory. For researchers in virology and drug development, understanding these configurations is crucial for designing diagnostics, antiviral therapeutics, and gene therapies. This guide provides a technical examination of these genomic structures, framing them within the context of viral genome organization and replication strategy research. The distinction between these forms extends beyond mere structure to encompass stability, replication fidelity, and specific functional roles in cellular processes, all of which present unique targets for scientific intervention [10].

Fundamental Structural Differences

The primary structural forms of nucleic acids are single-stranded and double-stranded, which dictate their biological functions and physical properties.

Single-Stranded Nucleic Acids consist of a single linear strand of nucleotides. This lack of a complementary strand results in a more flexible and less rigid structure. The bases are exposed, making them more accessible for interaction with proteins and other molecules but also more vulnerable to enzymatic degradation and chemical damage. This structural flexibility allows single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and DNA (ssDNA) to fold into complex three-dimensional shapes, including loops and hairpins, which are critical for their functional roles in catalysis and regulation [10]. Single-stranded DNA is found abundantly in viruses inhabiting extreme and marine environments [11].

Double-Stranded Nucleic Acids consist of two complementary strands intertwined in a helical formation. The two strands are held together by hydrogen bonding between nucleotide bases (adenine with thymine/uracil, and guanine with cytosine) and stack via hydrophobic interactions, creating a stable, stiff helical structure [10] [12]. This double-helix configuration protects the genetic information within its core, providing resilience against damage and serving as a stable repository for genetic information [10]. The persistence length of dsDNA is approximately 50 nm (150-200 base pairs), characterizing it as a semi-flexible polymer [12]. Most organisms utilize double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) as their genetic material [11].

Comparative Analysis: ssDNA vs. dsDNA

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Single-Stranded and Double-Stranded DNA

| Feature | Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Linear, single strand | Two complementary strands in a helical double helix [11] |

| Prevalence | Found in some viruses (e.g., Parvoviridae, Microviridae) [13] | Universal genetic material of most cellular organisms and many viruses [11] |

| Stiffness & Stability | Less stiff and less stable structure [11] | Stiffer and more stable structure [11] |

| Hydrogen Bonds | Absent between strands [11] | Present between complementary base pairs, stabilizing the helix [12] |

| Chargaff's Rule | Purine to pyrimidine ratio is variable; does not follow Chargaff's rule [11] | Purine to pyrimidine ratio is constant (∼1); follows Chargaff's rule [11] |

| Susceptibility | More exposed bases are susceptible to damage | Protected bases within the helix are less susceptible |

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Single-Stranded and Double-Stranded RNA

| Feature | Single-Stranded RNA (ssRNA) | Double-Stranded RNA (dsRNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Single strand, often with complex secondary structures (loops, hairpins) [10] | RNA with two complementary strands, forming an A-form helix [14] |

| Functional Roles | Coding for proteins (mRNA), gene regulation, catalysis | Genetic material for some viruses; key trigger for RNA interference and interferon response [14] |

| Stability | Flexible and versatile for diverse functions | Remarkably resistant to RNase A degradation [14] |

| Immune Recognition | Not a primary pathogen-associated molecular pattern | Potent trigger of innate immune responses in vertebrates [14] |

Viral Genome Organization and Replication Strategies

The Baltimore classification system categorizes viruses based on their genome configuration (ss or ds, DNA or RNA) and their replication strategy. This configuration is a primary driver of a virus's replication mechanism.

Single-Stranded DNA Viruses

Viruses with ssDNA genomes, such as those from the families Parvoviridae, Circoviridae, and Microviridae, possess small, compact genomes that have evolved to encode multiple proteins from limited genetic space [15]. A key structural feature across many icosahedral ssDNA viruses is the conserved jelly-roll motif of the capsid protein, which facilitates capsid assembly and stability [15]. These viruses typically employ a rolling circle replication mechanism. Upon entering the host cell, the ssDNA is converted into a double-stranded intermediate form by the host's DNA polymerases. This dsDNA intermediate then serves as a template for the transcription of viral genes and the production of new copies of the viral ssDNA genome.

Double-Stranded DNA Viruses

DsDNA viruses include some of the most complex viruses, such as adenoviruses and herpesviruses. Their replication strategy is often more straightforward, resembling cellular DNA replication. The viral dsDNA genome is transported to the host nucleus, where it utilizes the host's transcription machinery. Viral mRNA is transcribed directly from the dsDNA template and translated into viral proteins. Replication of the viral genome is typically semiconservative, using viral DNA polymerases that often incorporate proofreading and error-checking mechanisms to ensure high fidelity [16].

Single-Stranded RNA Viruses

This large and diverse group can be further divided into positive-sense [(+)ssRNA] and negative-sense [(-)ssRNA] viruses. The genome of (+)ssRNA viruses can directly function as mRNA, which is immediately translated by host ribosomes into viral proteins, including an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). This RdRp then synthesizes complementary (-)ssRNA strands, which serve as templates for new (+)ssRNA genomes. (-)ssRNA viruses, however, must carry their own RdRp within the virion. Upon entry, this polymerase transcribes the (-)ssRNA genome into complementary mRNA molecules for protein synthesis.

Double-Stranded RNA Viruses

DsRNA viruses, such as those in the Reoviridae family, protect their genomes from the host's immune system within a core particle. The viral RdRp within this core transcribes the dsRNA genome, using one strand to produce mRNA molecules that are extruded from the particle. These mRNAs serve for both translation and as templates for the synthesis of new genomic dsRNA, which remains within the capsid. The sequestration of dsRNA is critical because it is a potent trigger of the host's interferon response [14].

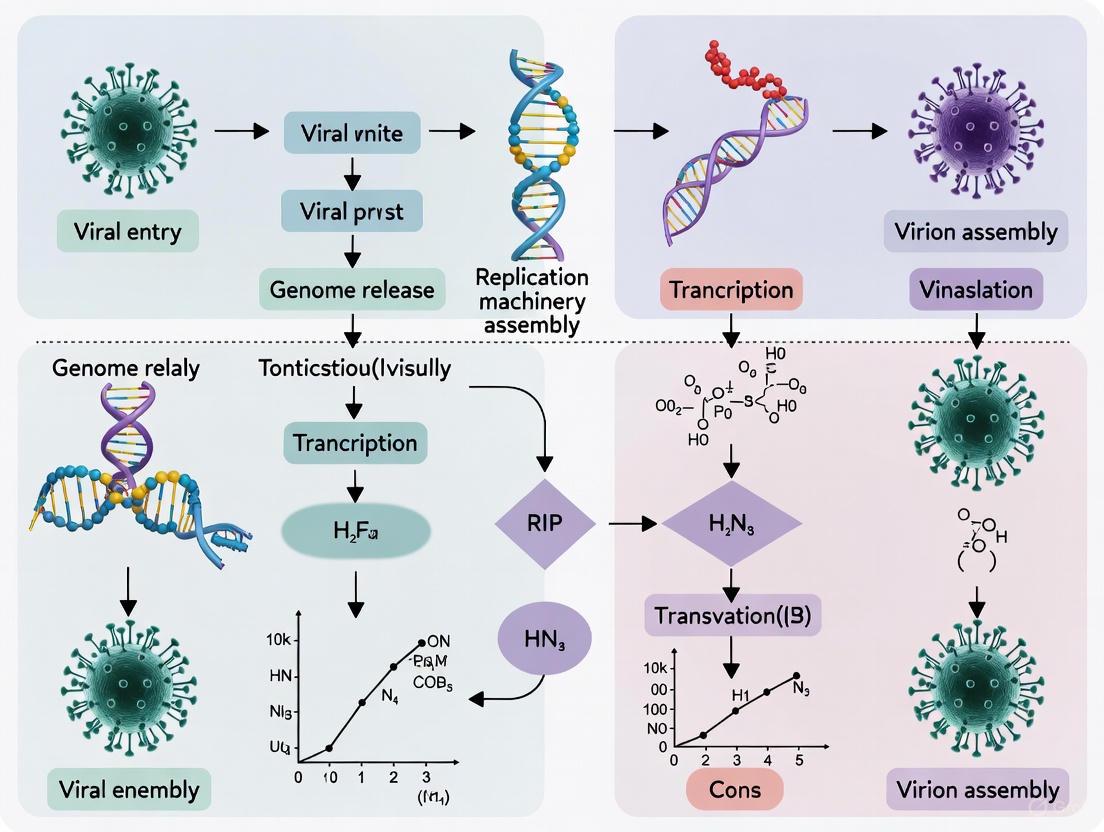

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental replication pathways for these different viral genome types.

Experimental Methodologies for Structural Analysis

Analyzing the structure and behavior of different genomic configurations requires specialized experimental protocols. The following section details key methodologies for working with and distinguishing between single-stranded and double-stranded nucleic acids.

Library Preparation for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

The choice between ssDNA and dsDNA library preparation methods significantly impacts the outcomes of sequencing studies, especially when dealing with fragmented or damaged DNA, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in liquid biopsies.

Table 3: Comparison of DNA Library Preparation Methods

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| dsDNA Library [17] | 1. End-repair of fragmented DNA.2. Ligation of adapters.3. PCR amplification (e.g., 10 cycles).4. Purification with AMPure XP beads (1:1 ratio). | Widely used and standardized protocols. | Insensitive to short, degraded, or single-stranded fragments with strand breaks [17]. |

| ssDNA Library [17] | 1. Denaturation of dsDNA into single strands.2. Adaptase reaction to prepare strand ends.3. Extension and adapter ligation.4. PCR amplification (e.g., 10-14 cycles).5. Multiple cleanup steps with varying bead ratios. | Enriches shorter, more degraded fragments; preserves library diversity; captures more ctDNA [17] [18]. | Lower mapping rate compared to dsDNA libraries [17]. |

| Pure-ssDNA Library [17] | Protocol similar to ssDNA library but skips the initial denaturation step to capture pre-existing single-stranded DNA in the sample. | Captures the endogenous ssDNA fraction; shows similar advantages to the standard ssDNA method [17]. | Not applicable for converting dsDNA into a sequencer-compatible library. |

Experimental Insight: A 2020 study comparing these methods for plasma cfDNA from cancer patients found that ssDNA and pure-ssDNA libraries had a significantly lower duplicate rate than dsDNA libraries (p<0.001 and p<0.01, respectively), indicating superior library complexity. Furthermore, ctDNA content and plasma genomic abnormality (PGA) scores were consistently higher in ssDNA-based libraries (p<0.005), attributed to their ability to capture smaller DNA fragments more representative of ctDNA [17] [18].

Structural Determination of Viral Capsids

For ssDNA viruses, structural capsidomics aims to understand the diversity of capsid architectures. The experimental workflow involves:

- Virus Purification: Culturing the virus and purifying viral particles from host cell components.

- Capsid Isolation: Separating the intact protein capsid from the viral genome and envelope (if present).

- Structural Determination:

- X-ray Crystallography: Growing high-quality crystals of the capsid proteins or entire capsids and solving the structure by analyzing X-ray diffraction patterns.

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): Rapidly freezing the capsid in a thin layer of vitreous ice and using an electron microscope to collect thousands of 2D images. These are then computationally reconstructed into a high-resolution 3D structure.

- Computational Modeling: With the increasing availability of viral genome sequences, predictive protein modeling programs like AlphaFold are used to extend structural insights to less-characterized virus families, allowing for comparative analysis of capsid protein arrangements and tessellation patterns [15].

To date, detailed capsid architectures have been resolved for 8 out of the 35 known ssDNA virus families, revealing variations in assembly mechanisms, symmetry, and structural adaptations [15].

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for analyzing viral capsid structures.

Detection and Characterization of dsRNA

Double-stranded RNA is a potent signaling molecule in innate immunity, and its detection is crucial in virology and immunology. Key properties and methods for its analysis include:

- RNase Resistance Assay: dsRNA is remarkably resistant to digestion by RNase A, an enzyme that degrades single-stranded RNA. This property is a classic biochemical method for distinguishing dsRNA from ssRNA [14].

- Physical Characterization: High molecular weight dsRNA can be characterized by:

- Hyperchromicity: dsRNA has a lower molar absorbance than ssRNA. Upon denaturation (melting), the absorbance increases (hyperchromic effect) [14].

- Sedimentation Coefficient: dsRNA molecules have sedimentation coefficients (s~20,w~) above 8–9 S [14].

- Melting Temperature (T~m~): dsRNA exhibits a cooperative temperature transition profile with ionic strength-dependent T~m~ values [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for Nucleic Acid Research

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [17] | For extraction and purification of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from plasma samples. |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit & ssDNA Assay Kit [17] | Fluorometric quantification of double-stranded and single-stranded DNA concentrations, respectively. |

| Agencourt AMPure XP Beads [17] | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads for post-PCR and size-selective purification of DNA libraries. |

| Rubicon Genomics ThruPLEX Kit [17] | An example of a commercial dsDNA library preparation kit for next-generation sequencing. |

| Swift Biosciences Accel-NGS 1S Plus Kit [17] | An example of a commercial ssDNA library preparation kit designed for low-input and degraded DNA samples. |

| RNase A [14] | An enzyme used to digest single-stranded RNA in a sample, helping to confirm the presence of double-stranded RNA via its resistance. |

| AlphaFold [15] | A computational tool for protein structure prediction, used to model capsid proteins of uncharacterized ssDNA viruses. |

Implications for Drug and Therapy Development

The distinct structural configurations of genomes present specific vulnerabilities and targets for therapeutic intervention.

- Targeting dsDNA: Many chemotherapeutic agents and antibiotics intercalate into or alkylate dsDNA, disrupting replication and transcription in rapidly dividing cells or pathogens. Gene therapies using dsDNA in plasmids or viral vectors (e.g., AAV, Lentivirus) face challenges such as limited carrying capacity and potential insertional mutagenesis [19].

- Targeting ssRNA: The mRNA vaccines developed during the COVID-19 pandemic are a prime example of leveraging ssRNA for therapy. Delivery of modified (+)ssRNA inside lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) allows host cells to directly translate them into antigenic proteins, eliciting an immune response.

- Exploiting dsRNA as a PAMP: The innate immune system recognizes dsRNA as a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP). Synthetic dsRNA analogs, such as poly(I:C), are used as immune adjuvants to stimulate antiviral states. Conversely, inhibiting the dsRNA sensors of pathogenic viruses can be a strategy for antiviral drug development [14].

- Advantages of ssDNA in Gene Therapy: Single-stranded DNA vectors are emerging as a non-viral alternative for gene editing. They offer reduced immunogenicity compared to viral vectors, a high carrying capacity (up to 10 kb), and allow for precise control over the sequence, making them ideal as donor templates for homology-directed repair (HDR) in CRISPR-based editing [19]. Their production is also more straightforward and cost-effective than manufacturing complex viral vectors [19].

The dichotomy between single-stranded and double-stranded genomes is a cornerstone of virology and molecular biology with profound practical implications. Single-stranded forms offer functional versatility and are critical for information transfer and regulation, while double-stranded forms provide genetic stability and fidelity. For researchers and drug developers, these configurations dictate viral replication pathways, inform the selection of experimental techniques like NGS library prep, and present unique targets for novel therapeutics and gene therapies. A deep understanding of these structural configurations, their biophysical properties, and the methods to analyze them is therefore indispensable for advancing research in viral pathogenesis, genomics, and the development of next-generation biomedical interventions.

Viral genome topology represents a fundamental determinant of replication strategy, gene expression, and evolutionary adaptability. As obligate intracellular parasites, viruses package their genetic material in diverse architectural forms—linear, circular, or segmented—each imposing distinct constraints and opportunities for interaction with host cell machinery [5] [20]. Understanding these architectural paradigms is crucial for elucidating viral life cycles and developing targeted therapeutic interventions. This technical guide examines the structural and functional implications of viral genome topologies within the broader context of viral genome organization and replication strategy research, providing researchers with advanced frameworks for classifying and investigating these pathogens. The classification of viruses based on genome structure has evolved from morphological approaches to systems incorporating biochemical composition and replication mechanisms, with the Baltimore classification scheme representing a pivotal advancement in correlating genome topology with mRNA synthesis pathways [20].

Fundamental Architectures of Viral Genomes

Viral genomes exhibit remarkable diversity in their topological arrangements, which directly influence their replication dynamics and interaction with host cellular machinery. The primary architectural configurations include linear, circular, and segmented formats, each with distinct structural and functional implications [5] [20].

Table 1: Classification of Viral Genomes by Topology and Nucleic Acid Composition

| Genome Topology | Nucleic Acid Type | Structural Features | Example Viruses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Monopartite genome; requires conversion to double-stranded form for transcription | Canine parvovirus [20] |

| Linear | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Direct mRNA transcription from DNA template; often large genomes | Herpes simplex virus, Smallpox virus [20] |

| Linear | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), positive sense | Genome functions directly as mRNA; high mutation rates | Common cold (picornavirus), Poliovirus [5] [20] |

| Linear | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), negative sense | Complementary to mRNA; requires viral RNA polymerase | Rabies virus, Influenza viruses [20] |

| Circular | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Closed circular structure; may integrate into host genome | Papillomaviruses, many bacteriophages [20] |

| Circular | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Requires conversion to double-stranded intermediate before replication | Dependent on context and virus family |

| Segmented | Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) | Genome divided into multiple segments; each encodes different proteins | Childhood gastroenteritis (rotavirus), Influenza viruses [20] |

| Segmented | Single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) | Multiple RNA segments; enables genetic reassortment | Influenza viruses [20] |

Linear genomes represent the simplest topological arrangement, with genetic material organized in a continuous linear sequence. These genomes may be composed of either DNA or RNA and exhibit varying replication strategies based on their nucleic acid composition. DNA viruses with linear genomes, such as herpesviruses, typically replicate in the host cell nucleus and utilize host DNA polymerase for replication [20]. RNA viruses with linear genomes constitute approximately 70% of all known viruses and demonstrate significantly higher mutation rates due to the error-prone nature of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases [5]. This elevated mutation rate facilitates rapid viral evolution and adaptation to new host environments, presenting challenges for both natural immune responses and therapeutic development.

Circular genomes form closed continuous structures that provide resistance to exonuclease degradation and enable replication strategies involving rolling circle mechanisms. In DNA viruses, circular genomes facilitate integration into host chromosomes, establishing persistent or latent infections [20]. The human papillomavirus (HPV) exemplifies this strategy, with its circular double-stranded DNA genome persisting episomally in infected cells and potentially integrating into host DNA during oncogenic progression [21].

Segmented genomes consist of multiple discrete nucleic acid molecules, each typically encoding distinct viral proteins. This modular organization enables genetic reassortment when two different viral strains co-infect a single host cell, dramatically accelerating viral evolution and potentially facilitating cross-species transmission [20]. Rotaviruses, possessing 10-12 segments of double-stranded RNA, exemplify this architectural strategy, with each segment coding for specific structural enzymes and capsid proteins [5].

Genome Topology and Replication Strategies

The architectural configuration of viral genomes directly determines their replication mechanisms and mRNA production pathways. The Baltimore classification system categorizes viruses into seven distinct groups based on their genome topology and the method of mRNA synthesis, providing a robust framework for understanding replication strategies [20].

Table 2: Baltimore Classification of Viruses Based on Genome Topology and Replication Strategy

| Group | Genome Type | Genome Topology | mRNA Production Method | Example Viruses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Double-stranded DNA | Linear or circular | Direct transcription from DNA template | Herpes simplex virus, Smallpox virus [20] |

| II | Single-stranded DNA | Linear or circular | Conversion to double-stranded form before transcription | Canine parvovirus [20] |

| III | Double-stranded RNA | Segmented (10-12 segments) | mRNA transcribed from RNA genome by viral RNA polymerase | Rotavirus [5] [20] |

| IV | Single-stranded RNA (+) | Linear | Genome serves directly as mRNA | Poliovirus, Rhinovirus [20] |

| V | Single-stranded RNA (-) | Linear or segmented | mRNA transcribed from RNA genome by viral RNA polymerase | Rabies virus, Influenza virus [20] |

| VI | Single-stranded RNA (+) | Linear (diploid) | Reverse transcription to DNA, integration into host genome, then transcription | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [20] |

| VII | Double-stranded DNA | Circular (with RNA intermediate) | Reverse transcription of RNA intermediate back to DNA | Hepatitis B virus [20] |

The replication of DNA viruses follows pathways that closely mirror cellular DNA synthesis. Group I viruses with double-stranded DNA genomes utilize host cell transcription machinery to directly generate mRNA, which is then translated into viral proteins [20]. These viruses often replicate in the host cell nucleus and may establish latent infections where the viral genome persists without active replication. Group II viruses with single-stranded DNA genomes must first be converted to double-stranded DNA through host DNA polymerases before transcription can proceed [20]. This additional replication step introduces potential vulnerability points that can be targeted by antiviral therapies.

RNA viruses employ more diverse replication strategies reflecting their genomic architecture. Group IV viruses with positive-sense single-stranded RNA genomes can immediately function as mRNA upon host cell entry, enabling rapid translation of viral replication proteins [20]. These viruses generate double-stranded RNA replicative intermediates during genome amplification, which serve as templates for producing additional positive-strand genomic RNA and shorter viral mRNAs [20]. Group V viruses with negative-sense RNA genomes require virally-encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerases to generate complementary mRNA strands before protein synthesis can occur [20]. The segmented nature of some Group V genomes, exemplified by influenza viruses, facilitates genetic reassortment and contributes to the emergence of novel pandemic strains.

Retroviruses (Group VI) and hepadnaviruses (Group VII) utilize reverse transcription steps in their replication cycles, transitioning between RNA and DNA forms. Retroviruses package two identical copies of their single-stranded RNA genome, which are reverse-transcribed into double-stranded DNA upon host cell entry [5]. This DNA intermediate integrates into the host genome, establishing a persistent provirus that serves as a template for mRNA production [20]. Hepatitis B virus (Group VII) exhibits a unique replication strategy involving an RNA intermediate, despite its DNA genome [20]. The partially double-stranded DNA genome is repaired to form completely double-stranded DNA, which is transcribed to produce both mRNA and pregenomic RNA. This RNA intermediate is subsequently reverse-transcribed back to DNA within newly assembling viral capsids [20].

Viral mRNA Production Pathways

Methodologies for Genome Architecture Analysis

Advanced methodologies for characterizing viral genome topology integrate high-throughput sequencing technologies with sophisticated computational approaches. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms have revolutionized viral discovery by enabling comprehensive analysis of complex viral populations within diverse biological samples [22]. The evolution of these technologies has progressed from early Sanger sequencing to modern third-generation platforms offering single-molecule resolution and real-time sequencing capabilities [22].

Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Approaches

Unbiased metagenomic and metatranscriptomic approaches allow for viral discovery without prior cultivation, facilitating the identification of novel viral lineages and unusual genome architectures [22]. These methodologies involve extracting total nucleic acids from clinical or environmental samples, followed by cDNA synthesis (for RNA viruses) and library preparation for high-throughput sequencing. The resulting sequence data enables simultaneous characterization of genome topology, gene content, and evolutionary relationships.

Recent advances in third-generation sequencing technologies, particularly long-read platforms from Pacific Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore Technologies, have dramatically improved resolution for complex viral genomes [22]. The MiniON portable sequencer has demonstrated particular utility in field-based applications, enabling rapid, culture-independent whole-genome sequencing of outbreak pathogens such as Nipah virus [22]. These long-read technologies facilitate complete genome assembly without fragmentation, providing unprecedented insights into genome architecture and organization.

Bioinformatics and Computational Tools

The analysis of viral sequencing data requires specialized bioinformatics pipelines and computational tools designed to handle the distinctive features of viral genomes. Advanced algorithms and machine learning models, including deep learning networks, random forests, and support vector machines, enable accurate viral genome classification, host prediction, and functional annotation [22].

Tools such as VIRify, VirHostNet, and DeepViral have been specifically developed for viral genome analysis, incorporating capabilities for identifying genome topology, segment boundaries, and recombination events [22]. The Serratus system represents a significant advancement in large-scale viral discovery, having re-analyzed petabase-scale sequence data to identify over 130,000 new RNA viruses through ultra-high-throughput sequence alignment focused on the conserved RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene [22].

Graph-based visualization methods have emerged as powerful approaches for analyzing complex transcript isoforms and genome arrangements. These methods represent sequencing reads as nodes in a network, with edges denoting sequence similarity, enabling researchers to identify splicing patterns, repetitive elements, and structural variations that may be challenging to detect using conventional alignment-based methods [23].

Genome Topology Analysis Workflow

Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

Cutting-edge research into viral genome topology requires specialized reagents and experimental systems tailored to the unique characteristics of different viral families. The following table summarizes essential research tools and their applications in viral architecture studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Genome Architecture Studies

| Research Reagent | Category | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencing Kits (Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit) | Sequencing Technology | Library preparation for transcriptome profiling | RNA virus discovery, splice variant analysis, metatranscriptomic studies [23] [22] |

| Portable Sequencing Platforms (Oxford Nanopore MiniON) | Sequencing Technology | Real-time, field-based genome sequencing | Outbreak investigation (Nipah virus), recombinant enterovirus identification [22] |

| Graphia Professional | Bioinformatics Visualization | Graph-based analysis of sequence assemblies | Visualization of complex transcript isoforms, identification of splicing patterns [23] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screening Libraries | Functional Genomics | Genome-wide loss-of-function screens | Identification of host restriction factors affecting viral replication [21] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Kits | Transcriptomics | Resolution of viral infection heterogeneity | Identification of infected cell types, analysis of viral quasispecies [22] |

| Host Restriction Factor Assays (IFITM proteins, APOBEC3G) | Biochemical Tools | Study of intrinsic immunity mechanisms | Investigation of viral entry blockade, genome editing effects on viral replication [21] |

| Metagenomic Analysis Pipelines (Kraken, BowTie, MegaBLAST) | Bioinformatics Tools | Taxonomic classification and read mapping | Viral discovery in diverse samples, read-to-read similarity analysis [23] |

The integration of single-cell sequencing technologies has revolutionized our understanding of viral heterogeneity and host-pathogen interactions at the cellular level. These approaches enable researchers to discern viral genomes with unprecedented resolution, revealing genetic diversity within infected cell populations and identifying specific cell types susceptible to infection [22]. Single-cell RNA sequencing has been successfully applied to detect viral transcripts in human skin biopsies infected with Merkel cell polyomavirus and human papillomaviruses, and to study the heterogeneity of influenza virus infections [22].

Functional genomics approaches, including cDNA genome-wide gain-of-function screens, RNA interference, and CRISPR-Cas9 genome-wide loss-of-function screens, have significantly advanced the discovery of host factors that restrict viral replication [21]. These methodologies have identified numerous host restriction factors—including IFITM proteins, TRIM family proteins, and APOBEC3G—that impede various stages of the viral life cycle by targeting essential steps such as viral entry, genome transcription, replication, and particle assembly [21].

Emerging therapeutic approaches leverage insights from viral genome topology to develop targeted interventions. mRNA-encoded nanobodies represent a promising frontier for antiviral design, enabling precise targeting of viral replication complexes [24]. Similarly, small molecule inhibitors that stabilize host restriction factors such as APOBEC3G offer potential strategies for enhancing intrinsic immunity against viral pathogens [21].

Viral genome topology serves as a fundamental organizing principle that dictates replication strategy, evolutionary trajectory, and host interaction dynamics. The architectural diversity of viral genomes—encompassing linear, circular, and segmented configurations—represents adaptive solutions to the challenges of intracellular parasitism, each with distinct implications for gene expression, genome stability, and transmission efficiency. Contemporary research methodologies, integrating advanced sequencing technologies with sophisticated computational approaches, have dramatically expanded our capacity to characterize viral genome architecture and elucidate its functional consequences. These insights provide critical foundations for developing novel therapeutic strategies that target topology-specific vulnerabilities across diverse viral families, ultimately enhancing our preparedness for emerging viral threats.

Viral genomes are under intense evolutionary pressure to minimize their physical size while maximizing their coding capacity. This pressure stems from the need for rapid replication, the high mutation rates inherent to viral replication machinery, and the physical constraints of capsid packaging [25]. To overcome these challenges, viruses have evolved two primary strategies for genomic compression: overlapping genes and polyprotein processing. These strategies allow viruses to encode a diverse proteome from a remarkably compact genomic sequence, directly influencing their replication strategy, pathogenicity, and evolutionary trajectory. Understanding these mechanisms provides crucial insights for developing antiviral therapeutics and advancing synthetic biology applications where genetic space is limited.

Overlapping Genes: A Mechanism forDe NovoProtein Creation

The Mechanism of Overprinting

Overlapping genes, also termed "dual-coding genes," are genomic regions translated in multiple reading frames to produce distinct proteins from the same nucleotide sequence [26]. They originate through a process called overprinting, where nucleotide substitutions in a pre-existing ("ancestral") gene allow the expression of a completely novel protein from an alternative reading frame while preserving the original gene's function [27] [28]. The newly expressed frame is considered a de novo gene.

The most common configurations are same-strand overlaps, classified based on the frame shift of the de novo gene relative to the ancestral gene: +1 (shift one nucleotide 3′) or +2 (shift two nucleotides 3′) [27]. These arrangements create a unique evolutionary constraint because a single nucleotide mutation can potentially alter the amino acid sequences of two different proteins simultaneously.

Table 1: Types and Properties of Gene Overlaps

| Overlap Type | Description | Example Virus | Genomic Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Overlap | One gene is entirely contained within another | ΦX174 (Gene E within Gene D) | 279 nt [27] |

| Terminal Overlap | Involves only the 3′ end of one gene and the 5′ start of another | ΦX174 (Gene A and Gene K) | Varies [27] |

| Antiparallel Overlap | Overlapping frames have opposite orientation | Rare, some in updated RefSeq | Varies [26] |

Evolutionary Drivers and Constraints

The evolution of overlapping genes represents a fascinating adaptive conflict. While they increase coding capacity, they simultaneously constrain the freedom of both sequences to evolve, as a mutation that is synonymous or beneficial for one protein may be non-synonymous and deleterious for the other [27] [26]. Several theories explain their abundance in viruses:

- Genome Compression: The prevailing theory posits that overlapping is a response to strong selection for small genome size, driven by faster replication and the physical constraints of the capsid [25].

- Generation of Novelty: Overprinting serves as a mechanism for de novo gene creation, producing proteins with novel folds and functions, often related to pathogenicity [27] [26].

- Regulatory Coordination: Overlaps can facilitate coordinated expression of functionally related proteins through coupled translation or transcription [25].

Despite the variation in total genome length across viruses, which spans three orders of magnitude, the absolute length of overlapping regions is highly constrained, almost never exceeding 1500 nucleotides. Similarly, viruses rarely possess more than four significantly overlapping genes, regardless of their overall genome size [25].

Functional Significance of De Novo Proteins

Proteins encoded by de novo frames often function as accessory proteins that are not central to viral replication or capsid assembly but are crucial in vivo for pathogenicity and spread [27]. Their functions include:

- Promoting systemic diffusion in host plants by forming ribonucleoprotein complexes [27].

- Evading innate host defenses by inhibiting interferon response or suppressing RNA silencing [27].

- Inducing host cell lysis, as seen with the E protein in bacteriophage ΦX174 [27].

A notable compositional bias of these de novo proteins is their enrichment in disorder-promoting amino acids, leading to more intrinsic structural disorder compared to non-overlapping proteins. This disorder may facilitate novel interaction modes and functions [27].

Detection, Analysis, and Experimental Validation of Overlapping Genes

Computational Detection and Genealogy Prediction

Accurately detecting overlapping genes is critical, as their oversight leads to erroneous interpretation of mutational studies. Computational methods exploit the unique evolutionary signatures imposed by dual coding constraints.

Sequence Composition Analysis: Overlapping coding regions differ significantly from non-overlapping regions in nucleotide and amino acid composition. They are enriched in high-degeneracy amino acids (whose codons can vary at the third position without changing the amino acid) and depleted in low-degeneracy ones. This bias alleviates evolutionary constraints by allowing more synonymous mutations in the ancestral frame [26]. Discriminant analysis can separate overlapping from non-overlapping genes with 97% accuracy and ancestral from de novo frames with nearly 100% accuracy [28].

Phylogenetic Distribution Method: This method infers genealogy by comparing protein distribution across related viruses. The protein with the widest phylogenetic distribution (found in outgroups and sister clades) is deemed ancestral, while the one with the most restricted distribution (unique to a specific lineage) is the de novo gene [27].

Codon Usage Correlation: The ancestral gene, having co-evolved with other viral genes, typically exhibits a codon usage bias that correlates more strongly with the overall genomic codon usage than the de novo gene does [27].

The following workflow outlines the primary computational and experimental methods for the discovery and validation of overlapping genes:

Experimental Validation Protocols

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation. Evidence is categorized as "reliable" or "to be confirmed" based on the strength of the data [29] [26].

Reliable Evidence involves:

- Immune Detection: Techniques like western blotting or immunofluorescence using specific antibodies to confirm the expression and size of the protein product from the overlapping frame.

- Mutational Analysis: Introducing mutations that specifically disrupt the de novo overlapping frame without altering the ancestral frame's amino acid sequence, followed by observation of a distinct phenotypic effect. This is often combined with mass spectrometry to verify the mutant's proteomic profile.

To-Be-Confirmed Evidence includes:

- In Vitro Translation: Demonstrating that the genomic region can produce two distinct proteins in a cell-free translation system, providing initial proof of dual coding capacity.

Advanced Tools for Genomic Analysis

The analysis of viral genomes, including the discovery of overlaps, is accelerated by modern bioinformatics tools.

- Vclust: An ultrafast tool that can analyze millions of viral genomes within hours, clustering them based on similarity and matching International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses classifications. It is invaluable for large-scale comparative genomics to identify conserved or unique overlapping regions [30].

- Generative Models: Cutting-edge approaches like ESM3 are being used to design overlapping gene sequences in silico, optimizing two protein functions within a single DNA sequence for synthetic biology applications [31].

Polyprotein Strategy: Proteolytic Processing for Multiprotein Production

Mechanism and Functional Logic

The polyprotein strategy is another powerful solution to genomic compression. Viruses encode long polypeptide chains (polyproteins) that are subsequently cleaved by viral or host proteases into multiple mature, functional proteins. This strategy allows a single transcriptional and translational event to produce the raw material for an entire functional module (e.g., replication proteins or structural proteins).

The key advantage lies in the coordinated production of stoichiometric amounts of proteins that must work in concert. It also simplifies gene regulation by minimizing the number of promoters and regulatory sequences required. The classic example is the P1 region of potyviruses, which is processed into multiple structural capsid proteins. A critical nuance is the discovery of the pipo gene, which overlaps the P1 polyprotein region and is essential for viral replication, a function initially misattributed to the P1 polyprotein itself [26].

Experimental Analysis of Polyproteins

Studying polyproteins requires methods to identify cleavage products and their functional roles.

- Proteogenomics: This method integrates genomic data with mass spectrometry-based proteomic data to empirically map all expressed peptides, confirming the cleavage sites of polyproteins and potentially revealing novel or alternative processing events [32].

- Ribosome Profiling (Ribo-seq): This technique provides a snapshot of all ribosome-protected mRNA fragments, revealing which regions of the genome are actively being translated. It can identify translated overlapping genes embedded within polyprotein ORFs or unconventional translation start sites [32].

- Inhibitor Studies: Using drugs like retapamulin that inhibit translation initiation allows Ribo-seq to specifically capture sites of translation initiation, helping to delineate the start points of individual proteins within a polyprotein or overlapping frame [32].

The following diagram illustrates the polyprotein synthesis and processing pathway, alongside the potential for embedded overlapping genes:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Studying Overlapping Genes and Polyproteins

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features / Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Retapamulin | Translation initiation inhibitor used in Ribo-seq. | Enables precise mapping of translation initiation sites in bacterial systems; revealed new initiation sites in E. coli [32]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Immune detection of proteins from overlapping frames. | Used in Western Blot (WB) and Immunofluorescence (IF) to confirm expression and sub-cellular localization of de novo proteins [26]. |

| Curated Dataset of Overlapping Genes | Benchmarking for computational prediction tools. | A high-quality dataset of 80+ experimentally proven viral overlapping genes for training and validating detection algorithms [26]. |

| Vclust Software | Ultrafast comparison and clustering of viral genomes. | Analyzes millions of sequences in hours; identifies related genomes and classifies novel viruses [30]. |

| Generative Model (ESM3) | Computational design of overlapping gene pairs. | Designs novel, functional overlapping sequences for synthetic biology and stabilized genetic constructs [31]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Proteomic validation of protein expression and polyprotein processing. | Identifies peptides from de novo frames and maps polyprotein cleavage sites via proteogenomics [32]. |

Overlapping genes and polyprotein strategies represent elegant evolutionary solutions to the problem of genomic compression in viruses. Overprinting allows for the de novo creation of accessory proteins critical for host interactions and pathogenicity, while polyproteins enable the coordinated production of multiple proteins from a single open reading frame. The study of these mechanisms has been revolutionized by advanced computational tools like Vclust and generative models, and experimental techniques like proteogenomics and ribosome profiling.

Future research will focus on systematically discovering overlapping genes in major viral pathogens and eukaryotic genomes, where they are likely abundant but under-annotated. Furthermore, the principles of gene overlap are being harnessed in synthetic biology to create robust genetic circuits and biotherapeutics with built-in safeguards against mutation and horizontal gene transfer [31]. Understanding these viral strategies not only deepens our knowledge of viral evolution and pathogenesis but also provides powerful engineering principles for biotechnology.

Gene expression regulation is a complex process essential for cellular function and adaptation. Two sophisticated mechanisms that significantly expand the functional diversity of the proteome are alternative splicing (AS) and programmed ribosomal frameshifting (PRF). Within the context of viral genome organization and replication strategy research, understanding these mechanisms is paramount. Viruses, as obligate intracellular parasites, have evolved to hijack host cellular machinery and often utilize or manipulate these very processes to enable their replication and evade host immune responses. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of AS and PRF, detailing their core mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and quantitative characteristics, with a particular emphasis on their roles in viral replication and host-pathogen interactions. The insights gained are critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to develop novel antiviral therapeutics.

Alternative Splicing: Mechanism and Analysis

Core Splicing Machinery and Regulation

Alternative splicing (AS) is a vital post-transcriptional process that allows a single gene to generate multiple mRNA isoforms, thereby greatly enhancing transcriptomic and proteomic diversity [33]. The process is catalyzed by the spliceosome, a large macromolecular complex composed of five small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, U6) and numerous proteins, forming small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) [33].

Splicing regulation is governed by a combination of cis-acting elements and trans-acting factors:

- Cis-acting elements: These are specific nucleotide sequences within the pre-mRNA that serve as binding sites for regulatory factors. They include the 5' and 3' splice sites, the branch point sequence, the polypyrimidine tract, and four primary types of splicing regulatory elements (SREs): Exon Splicing Enhancers (ESEs), Intron Splicing Enhancers (ISEs), Exon Splicing Silencers (ESSs), and Intron Splicing Silencers (ISSs) [33].

- Trans-acting factors: These are typically RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that bind to the SREs to promote or repress spliceosome assembly. Two major classes of RBPs are the SR proteins (SRSFs), which generally enhance exon inclusion, and the HNRNP proteins, which often promote exon skipping [33]. The binding of these factors can be competitive, finely tuning the splicing outcome.

Splicing and Viral Replication

The interface between host splicing machinery and viral replication is a critical battleground. Viruses can manipulate host AS to suppress antiviral responses and to generate the protein diversity needed for their own replication from a compact genome. Conversely, host cells can deploy AS-related mechanisms as a defense. For instance, AS can introduce premature termination codons (PTCs) via frameshifts, leading to the degradation of viral or host transcripts through the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway [34]. Research in sepsis patients has demonstrated an upregulated rate of PTC-introducing splicing events associated with disease states, highlighting a potential global host response to severe stress, including infection [34].

Table 1: Key Splicing Regulatory Elements and Their Functions

| Element Type | Location | Function | Common Binding Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon Splicing Enhancer (ESE) | Exon | Promotes exon inclusion | SRSFs |

| Intron Splicing Enhancer (ISE) | Intron | Promotes exon inclusion | SRSFs, other activators |

| Exon Splicing Silencer (ESS) | Exon | Promotes exon skipping | HNRNPs |

| Intron Splicing Silencer (ISS) | Intron | Promotes exon skipping | HNRNPs, other repressors |

Experimental Protocol: Predicting NMD from Splicing Events

The following computational pipeline allows researchers to predict and quantify how splicing events lead to transcript degradation via NMD, which is particularly useful for analyzing host responses to viral infection or other cellular stresses [34].

- RNA Sequencing: Perform whole-blood, deep RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq). Using a non-poly(A) selection protocol is crucial to capture all transcripts, including those without poly(A) tails that might be degraded.

- Read Mapping and Splicing Analysis: Map the sequenced reads to the reference human genome. Process the mapped reads using a splicing analysis tool like Whippet to identify and quantify statistically significant alternative splicing events.

- Frameshift and PTC Identification: The core of the pipeline involves computing how the identified splicing events alter the reading frame. The tool analyzes whether an event introduces a frameshift that creates a premature termination codon (PTC).

- NMD Prediction: A PTC-dependent NMD is predicted if the identified PTC is located more than 50-55 nucleotides upstream of the final exon-exon junction. The pipeline then calculates a probability or rate of NMD for the affected transcripts.

- Integration with Differential Expression: Correlate the predicted NMD events with differential gene expression data from the same samples to understand the functional impact on the transcriptome.

Diagram 1: NMD Prediction from Splicing Analysis Workflow.

Programmed Ribosomal Frameshifting: A Viral Replication Strategy

Mechanism and Viral Utilization

Programmed ribosomal frameshifting (PRF) is a translational recoding event where a proportion of elongating ribosomes shift their reading frame by one or two nucleotides at a specific mRNA signal. This allows the synthesis of multiple distinct proteins from a single mRNA transcript [35]. While phylogenetically rare in vertebrate cellular genes, PRF is a common and essential strategy employed by many viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, HIV-1, and Influenza A virus, to regulate the stoichiometric production of their proteins from a compact genome [35] [36].

The canonical -1 PRF mechanism, used by coronaviruses and retroviruses, involves two key elements:

- A 'Slippery' Sequence: Typically of the form XXXYYYZ (where XXX represents any three identical nucleotides), where the tRNAs in the P- and A-sites of the ribosome can unpair and re-pair in the -1 frame.

- A Downstream RNA Structural Element: An RNA secondary structure, such as a pseudoknot or a stem-loop, located 5-9 nucleotides downstream of the slippery sequence. This structure momentarily stalls the ribosome, increasing the probability of the tRNAs slipping into the alternative frame [36].

In coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2, a -1 PRF event between overlapping open reading frames ORF1a and ORF1b is critical. Ribosomes that translate ORF1a without frameshifting produce polyprotein pp1a. However, a proportion of ribosomes undergo -1 PRF at the slippery sequence, allowing translation to continue into ORF1b and producing the longer pp1ab polyprotein, which contains RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and other essential non-structural proteins for the replication-transcription complex [36].

A Conserved +1 PRF in a Human Gene

Recent research has identified a conserved +1 PRF event in the human gene PLEKHM2, which is not of viral origin [35]. This finding is significant as it represents a rare, functional example of PRF in a vertebrate cellular gene that generates two proteins from one mRNA.

- PRF Signal: The +1 PRF signal in PLEKHM2 is UCCUUUCGG, nearly identical to the +1 PRF site in influenza A virus.

- Stimulatory Element: Unlike viral -1 PRF, the PLEKHM2 +1 PRF appears to be primarily dependent on its slippery sequence, with a downstream stem-loop structure having a minimal stimulatory role [35].

- Biological Consequence: Frameshifting produces a "transframe protein," PLEKHM2-FS. This isoform lacks the autoinhibitory C-terminal domain of the canonical protein and contains a novel α-helical domain, which promotes self-association and enables its role in lysosome transport without requiring activation by ARL8. The functional necessity of both proteoforms was demonstrated in cardiomyocytes, where only the combined reintroduction of both the canonical and frameshifted proteins could restore normal contractility after knockout [35].

Table 2: Quantitative Frameshifting Efficiencies and Mechanisms

| Organism/Gene | Frameshift Type | Slippery Sequence | Stimulatory Element | Frameshift Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (ORF1a/1b) | -1 | UUU_AAAC | RNA Pseudoknot | Not explicitly quantified in results |

| HIV-1 | -1 | UUU_UUUA | RNA Pseudoknot | ~2% [35] |

| Influenza A Virus | +1 | UCCUUUCGU | Presumably none | ~1% [35] |

| Human PLEKHM2 | +1 | UCCUUUCGG | Stem-loop (minor role) | ~1.3% [35] |

| Human OAZ1 (Antizyme) | +1 | Not specified in results | Polyamine stimulation | 32.5% (Baseline) [35] |

Experimental Protocol: Dual Luciferase Assay for PRF Efficiency

The dual luciferase reporter assay is a standard method for quantitatively measuring PRF efficiency in living cells [35]. The following protocol is adapted from studies on PLEKHM2.

- Vector Construction: Clone the putative PRF cassette (including the slippery site and flanking sequences, approximately 50-100 nt) from the gene of interest (e.g., PLEKHM2) into a specialized dual luciferase vector. In this vector, the test sequence is inserted between the coding sequences of two distinct luciferase enzymes (e.g., Renilla and firefly luciferase). The construct is engineered such that:

- In-Frame (No FS) Translation: Produces only Renilla luciferase.

- Successful Frameshift Translation: Links the Renilla and firefly luciferase sequences into a single, continuous open reading frame, producing a fusion protein.

- Cell Transfection and Lysate Preparation: Transfect the constructed plasmid into an appropriate cell line (e.g., HEK293T cells). After a suitable incubation period (e.g., 24-48 hours), lyse the cells to harvest the proteins.

- Luciferase Activity Measurement: Using a luminometer, sequentially measure the enzymatic activity of both luciferases from the same sample. First, measure Renilla luciferase activity (Rluc). Then, quench the Rluc reaction and activate the firefly luciferase reaction (Fluc).

- Data Analysis and Efficiency Calculation: The Renilla luciferase activity corresponds to the total number of translation events. The firefly luciferase activity corresponds only to the translation events that resulted in a frameshift. PRF efficiency is calculated as: PRF Efficiency (%) = (Fluc_activity / Rluc_activity) × 100 To confirm the result is due to frameshifting and not other artifacts (e.g., cryptic promoters/splicing), a negative control with a mutated, non-slippery sequence must be tested in parallel.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Studying Splicing and Frameshifting

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Dual Luciferase Reporter System | Quantifying PRF efficiency in vivo. | Commercial kits available; used with custom PRF cassette inserts [35]. |

| Ribosome Profiling (Ribo-seq) | Genome-wide mapping of translating ribosomes; can identify PRF events. | Reveals ribosome densities at frameshift sites [35]. |

| ColabFold / AlphaFold | Predicting protein structures, including novel folds from frameshifted isoforms. | Used to model the novel α-helical domain in PLEKHM2-FS [35]. |

| Non-poly(A) Selected RNA-Seq | Comprehensive transcriptome sequencing for splicing analysis. | Captures non-polyadenylated transcripts crucial for NMD studies [34]. |

| Whippet Software | Quantifying alternative splicing events from RNA-Seq data. | Used to identify splicing changes leading to frameshifts and PTCs [34]. |

| VITAP (Viral Taxonomic Pipeline) | Classifying DNA/RNA viral sequences from meta-omic data. | Aids in viral replication research by identifying and categorizing viruses [37]. |

| Spermidine / Polyamines | Small molecule stimulators of +1 PRF. | Can be used to experimentally modulate PRF efficiency, as in OAZ1 and PLEKHM2 [35]. |

Diagram 2: Coronavirus Replication and Subgenomic RNA Synthesis.

Decoding the Life Cycle: Methodologies for Studying Viral Replication and Genome Organization

Cryo-Electron Microscopy and Tomography for Asymmetric Genome Analysis

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) have revolutionized structural biology, enabling the visualization of asymmetric biological complexes in their native states at unprecedented resolutions. These techniques are particularly transformative for studying viral genome organization and replication, where asymmetric assemblies—such as pleomorphic virions, ribonucleoprotein complexes, and conical capsids—play critical functional roles. Unlike traditional structural methods that require crystallization, cryo-EM/ET preserves hydrated, native structures, allowing researchers to capture transient intermediates and conformational heterogeneity essential for understanding viral life cycles [38] [39]. The "resolution revolution," driven by direct electron detectors and advanced computational processing, has positioned cryo-EM/ET as indispensable tools for elucidating the structural basis of viral replication strategies [38] [39].

Within virology, cryo-ET specifically enables the study of asymmetric viral genomes within their architectural context. Many viruses, including influenza and HIV-1, package their genomes in non-uniform, asymmetric configurations that are incompatible with traditional averaging techniques. In situ cryo-ET provides nanometer-resolution snapshots of these complexes directly within infected cells, revealing how viral genomes are organized, trafficked, and released [40] [41]. This technical guide explores how cryo-EM/ET methodologies are unlocking new understandings of asymmetric viral genome analysis, with direct implications for antiviral drug development and fundamental virology.

Technical Foundations of Cryo-EM and Cryo-ET

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Advantages

Cryo-EM and cryo-ET share a common foundation in imaging vitrified biological samples maintained at cryogenic temperatures (approximately -196°C). This process preserves native hydration and structure by rapidly freezing samples in liquid ethane to form amorphous ice, avoiding crystalline ice damage [38]. The key distinction lies in their imaging approaches and applications: single-particle cryo-EM reconstructs high-resolution 3D structures by computationally aligning and averaging thousands of identical, randomly oriented particles [39]. In contrast, cryo-ET tilts a single sample through a range of angles (typically ±60°) to collect a series of 2D projections (a tilt-series) that are reconstructed into a 3D tomogram, ideal for visualizing unique, asymmetric structures in their cellular context [42].