Viral Host Range and Transmission Modes: Mechanisms, Prediction, and Clinical Impact

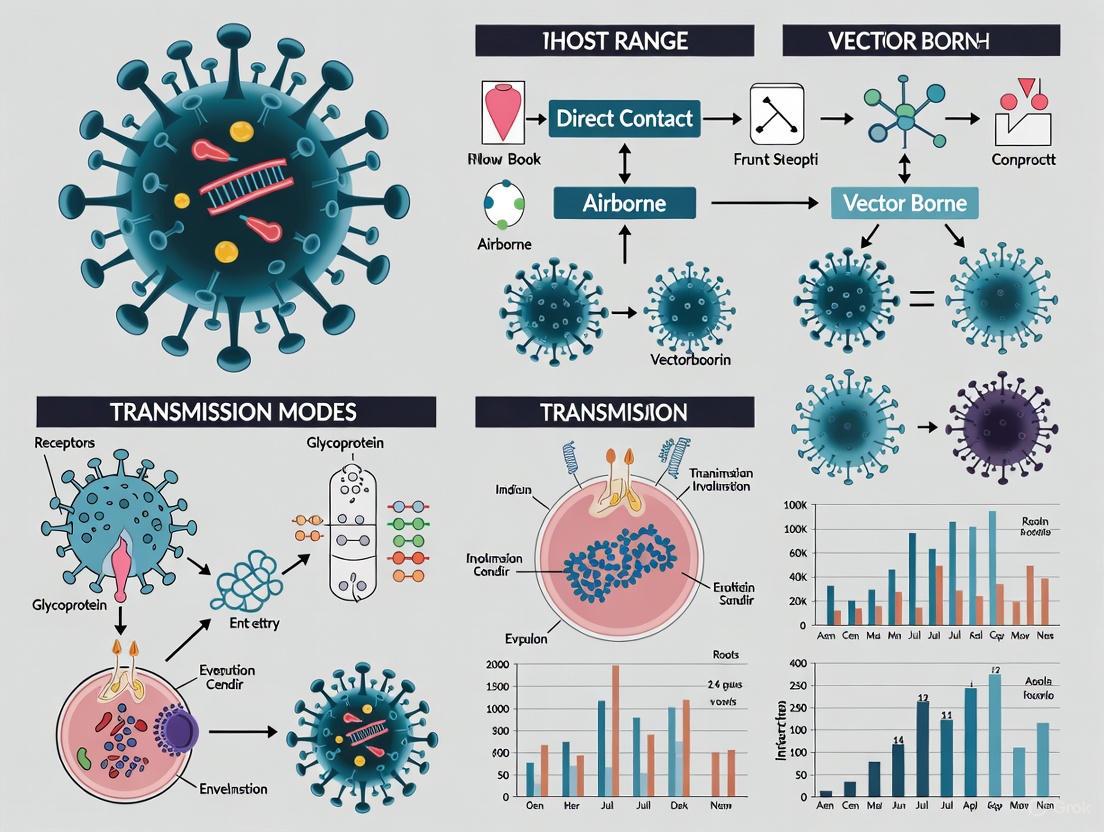

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the principles governing viral host range and transmission modes, critical factors in understanding viral epidemiology and pathogenesis.

Viral Host Range and Transmission Modes: Mechanisms, Prediction, and Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the principles governing viral host range and transmission modes, critical factors in understanding viral epidemiology and pathogenesis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biological mechanisms—from molecular tropism to ecological dynamics—that determine how viruses infect and spread. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodological advances, including machine learning for predicting transmission routes and computational host prediction tools. It further addresses challenges in managing viral spillover and optimizing intervention strategies, while evaluating and comparing different predictive models and their validation. This synthesis aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to anticipate viral spread, design targeted therapeutics, and develop effective public health measures.

The Fundamentals of Viral Host Range and Transmission Mechanisms

The host range of a virus is a fundamental biological property defined as the number of host species that a virus can infect and within which it can successfully replicate [1]. This spectrum of viral strategies exists on a continuum, with specialist viruses infecting one or a few closely related species at one extreme, and generalist viruses capable of infecting several different species, sometimes across different taxonomic families, at the other [2]. Understanding the evolutionary mechanisms and ecological implications underlying these strategies is critical for managing viral diseases, predicting emergence events, and developing effective therapeutic interventions.

The intrinsic evolvability of viruses, afforded by their large population sizes, short generation times, and high mutation rates, facilitates host range changes that can eventually lead to epidemics caused by emergent new viruses [3]. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the factors driving the evolution of specialist and generalist viral strategies, the molecular constraints governing these adaptations, and the experimental approaches used to investigate them, providing a framework for ongoing research in viral host range and transmission.

Evolutionary Mechanisms and Trade-offs

Selective Pressures Driving Specialization

In stable, homogeneous environments, natural selection typically favors the evolution of specialist viruses. Empirical evidence from numerous in vitro evolution experiments demonstrates that viral adaptation to a specific host is often coupled with fitness losses in alternative hosts [3]. A foundational study on Bacteriophage ØX174, which naturally infects Escherichia coli, undertook experimental evolution in Salmonella enterica. After just 11 days of selection, the phage showed an almost 700-fold fitness increase in the new host. However, this adaptation came at a substantial cost: its replicative fitness in the original E. coli host was almost completely eliminated [3].

Similar patterns have been observed across diverse virus families. RNA arboviruses like Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV), when evolved in a single cell type, consistently become specialists, increasing their replicative fitness in the new host while paying fitness costs in alternative host cell types, including their original one [3]. Plant viruses exhibit parallel trends; for instance, Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) genotypes that expanded their host range to plants bearing the TuRB01 resistance gene showed replicative fitness penalties ranging from approximately 32% to 100% in wildtype turnips [3].

The primary genetic mechanisms generating these fitness trade-offs are antagonistic pleiotropy and mutation accumulation [3]. Antagonistic pleiotropy occurs when mutations that are beneficial for infection in one host are directly detrimental in another. Mutation accumulation, in contrast, involves neutral mutations drifting to fixation in genes non-essential for the current host but potentially critical for infection of an alternative host. While both mechanisms result in differential fitness effects across hosts, the former is driven by natural selection, and the latter by genetic drift [3].

Conditions Favoring Generalist Viruses

Despite the advantages of specialization, generalist viruses persist successfully in nature, particularly under conditions of environmental heterogeneity. When hosts fluctuate in time or space, selective pressures differ, creating opportunities for generalist viruses to evolve [3]. Experiments with VSV and EEEV populations that alternated between two different cell types demonstrated that viruses could achieve replicative fitness values in each host similar to those reached by lineages evolved exclusively on each single host, effectively becoming generalists without apparent fitness trade-offs [3].

The rate of migration or alternation between hosts appears crucial. Research has shown that increasing the migration rate among heterogeneous cell types selects for generalist viruses with improved replicative fitness across all alternative environments [3]. This spatial heterogeneity mimics conditions within complex host organisms, where a virus encounters different tissues, cell types, and physiological barriers.

Genome architecture may also correlate with host range breadth. A 2025 analysis suggests that multipartite and segmented viruses (which package their genomes into multiple particles) have broader host ranges than monopartite viruses (with single genome segments) [4] [5]. This organization may facilitate adaptation to diverse hosts by allowing for rapid reassortment of genome segments or changes in their relative frequencies (the "genome formula"), potentially tuning gene expression for different host environments [5].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Specialist and Generalist Viral Strategies

| Feature | Specialist Viruses | Generalist Viruses |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Infect one or few closely related host species [2] | Infect several different species, possibly from different families [2] |

| Evolutionary Context | Stable, homogeneous host environments [3] | Fluctuating, heterogeneous host environments [3] |

| Fitness Trade-off | Often high (antagonistic pleiotropy) [3] | Potentially low under certain conditions [3] |

| Genetic Mechanisms | Mutation accumulation, antagonistic pleiotropy [3] | Reassortment (for segmented/multipartite), genome formula tuning [5] |

| Examples | Dengue virus, Mumps virus [3] | Cucumber mosaic virus, Influenza A virus [3] |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Research across viral systems has yielded quantitative insights into the costs of host-range expansion and the dynamics of adaptation. The following table summarizes key experimental findings:

Table 2: Quantitative Evidence of Fitness Trade-offs in Virus Evolution

| Virus | Experimental System | Fitness Gain in New Host | Fitness Cost in Ancestral Host | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteriophage ØX174 | Adaptation from E. coli to S. enterica | ~700-fold increase | Nearly complete loss (fitness ~0) | [3] |

| Turnip Mosaic Virus (TuMV) | Adaptation to resistant plants (TuRB01) | Successful host range expansion | 32% to 100% fitness reduction in wildtype host | [3] |

| Plum Pox Virus (PPV) | Serial passage in Pisum sativum (herbaceous host) | Increased infectivity, viral load & virulence | Reduced transmission efficiency in original peach tree host | [3] |

| Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) | Serial passage in pepper | Increased viral load & virulence | No replicative fitness increase in ancestral tobacco host | [3] |

These quantitative findings consistently demonstrate that host-range expansion is often a costly trait, supporting the jack-of-all-trades paradigm wherein generalists may be masters of none [3]. However, exceptions exist, as seen with Foot-and-mouth disease virus, where adaptation to hamster kidney fibroblasts serendipitously expanded its host range to include cells from monkeys and humans [3].

Methodologies for Studying Host Range

Experimental Evolution Protocols

Directed in vitro evolution is a powerful approach for investigating viral host range dynamics. The Appelmans protocol, for instance, is a method used to expand the host range of bacteriophages through serial passage and recombination [6]. In this protocol, a phage cocktail is cyclically exposed to a panel of bacterial hosts. Phages that successfully infect new hosts are isolated and propagated, effectively "training" the phages to broaden their infectivity. A recent application of this protocol to generate phages targeting carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) successfully created output phages with expanded host ranges. These were identified as recombinant derivatives originating from prophages induced from the encountered bacterial strains [6]. However, a significant caveat was that the expanded host range phages exhibited limited stability, raising questions about their therapeutic suitability [6].

Another common approach involves serial passage experiments in a single novel host. Viruses are serially passaged in a new host cell type or organism, and their evolving fitness is tracked in both the new and ancestral environments. This method has been extensively used with viruses like VSV, EEEV, and plant viruses to quantify the tempo and strength of adaptation and the associated trade-offs [3].

Computational Prediction of Host-Virus Interactions

Modern research increasingly leverages machine learning (ML) to predict virus-host interactions, including host range. One ML approach for predicting strain-specific phage-host interactions uses protein-protein interactions (PPI) as key features [7]. In this method:

- Genomic Sequencing: Phage and bacterial genomes are sequenced and assembled.

- Gene Annotation: Open reading frames are predicted and annotated.

- Protein Domain Identification: Protein domains are identified using tools like HMMER against databases such as PFAM.

- PPI Prediction: Interactions between phage and bacterial proteins are predicted by comparing them to reference PPI databases (e.g., PPIDM), assigning a reliability score to each domain-domain interaction.

- Model Training and Prediction: The PPI data, combined with experimental host-range data, are used to train ML models (e.g., LightGBM ensembles) capable of predicting infection outcomes for novel phage-bacteria pairs [7].

Another computational framework analyzes viral evolutionary signatures to predict transmission routes, which are intrinsically linked to host range [8]. This method engineers hundreds of features from viral genomes, including genomic composition, codon usage bias, and structural properties, and integrates them with virus-host association data to train predictive models. Such models can achieve high accuracy (ROC-AUC = 0.991) in classifying transmission routes, providing early insights during outbreaks [8].

Diagram 1: ML Host Range Prediction Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Viral Host Range Research

| Research Tool | Specific Examples / Formats | Primary Function in Host Range Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Lines | BHK (Baby Hamster Kidney) cells, Mosquito cells (e.g., C6/36), various mammalian and insect cell lines [3] | Provide in vitro host systems for serial passage experiments and replicative fitness assays. |

| Bacterial Host Panels | Historic collections of target bacteria (e.g., Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli strains) [7] | Used in quantitative host range assays to determine phage infectivity spectrum. |

| Plant Host Variants | Wildtype and resistant genotype plants (e.g., turnips with TuRB01 gene) [3] | Enable quantification of fitness trade-offs associated with host-range expansion in complex organisms. |

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina Nextera XT DNA library prep kit, Phage DNA isolation kits (e.g., Norgen) [7] | Facilitate genomic sequencing of viral and host genomes for mutation tracking and ML feature generation. |

| Bioinformatics Software | HMMER, PFAM database, PPIDM, Fastp, Unicycler, CheckV [7] | Enable genome assembly, annotation, and prediction of protein-protein interactions for computational models. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | LightGBM [8] [7] | Power predictive models for classifying host-range and transmission routes based on genomic features. |

The dichotomy between specialist and generalist viral strategies is governed by a complex interplay of evolutionary genetics, ecological context, and molecular constraints. While specialization is favored in stable environments due to fitness trade-offs like antagonistic pleiotropy, generalists can evolve and persist in heterogeneous landscapes through mechanisms that mitigate these costs, potentially including genomic architectures like multipartitism.

Future research will be increasingly propelled by computational approaches that integrate viral genomic features with protein interaction data to predict host range and transmission potential in silico [8] [7]. Furthermore, advanced experimental evolution protocols continue to provide mechanistic insights into the genetic basis of host switching and adaptation [6]. Understanding these dynamics is not merely an academic pursuit but is critical for public health, as the majority of emerging viral diseases result from host shift events [2]. By defining the principles governing viral host range, researchers can better anticipate and mitigate the threats posed by emerging viral pathogens.

Viral tropism, defined as the specificity of a virus for infecting a particular host, cell type, or tissue, is a fundamental determinant of disease pathogenesis, transmission dynamics, and clinical outcomes [9] [10]. This selective infection is governed by molecular interactions between viral proteins and host-cell factors, which ultimately regulate host range, tissue targeting, and viral pathogenesis [11]. At the core of these interactions are host receptors, co-receptors, and a suite of host proteins that facilitate viral entry and establish productive infection [12] [13]. Understanding these molecular determinants is crucial for defining disease mechanisms, predicting spillover risk, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies across a One Health framework [13].

The initial interaction between a virus and its host cell can be viewed as a "lock-and-key" system, where viral attachment proteins serve as the "key" that unlocks cells by interacting with receptor "locks" on the host-cell surface [11]. These interactions represent critical regulatory steps in the viral life cycle, influencing not only attachment but also entry, intracellular trafficking, and activation of signaling events necessary for successful infection [12] [11]. This review provides an in-depth examination of the molecular mechanisms governing viral tropism, with particular emphasis on receptor usage, co-factor dependencies, and experimental approaches for studying these interactions within the broader context of viral host range and transmission modes.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Viral Entry

Viral Entry Pathways

Viruses employ distinct strategies to enter host cells, with the specific pathway determined by viral structure, receptor interactions, and host cell type [12]. The major entry mechanisms include:

Endocytosis: The predominant entry mechanism for many viruses, involving cellular internalization through membrane invagination [12]. This process can be further categorized into:

- Clathrin-mediated endocytosis: Characterized by clathrin-coated pits that internalize to form vesicles destined for early endosomes with an acidic environment (pH 6.5-5.5) [12].

- Caveolin-mediated endocytosis: Occurs via caveolae, membrane invaginations associated with caveolin and lipid rafts, though the nature of "caveosomes" remains controversial [12].

- Non-clathrin non-caveolin-mediated endocytosis: Less characterized pathways that may require receptor-mediated conformational transitions for cargo internalization [12].

Membrane Fusion: Specific to enveloped viruses, involving direct fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, often facilitated by viral glycoproteins [12] [14].

Direct Penetration: Utilized by non-enveloped viruses, where the viral capsid interacts directly with host membranes to deliver genetic material [12].

These entry pathways are not mutually exclusive, and viruses may employ different mechanisms depending on cell type, receptor availability, and environmental conditions [12].

Structural Determinants: Enveloped vs. Non-enveloped Viruses

Virus structure fundamentally influences entry mechanisms and tropism determinants. Enveloped viruses possess an outer lipid bilayer derived from host cell membranes, studded with viral glycoproteins that facilitate attachment and entry [9]. Examples include HIV, Influenza virus, Herpesviruses, and coronaviruses like SARS-CoV-2 [9]. Their envelopes make them relatively sensitive to environmental stressors but allow for flexible entry mechanisms and rapid antigenic variation [9].

Non-enveloped viruses lack this lipid membrane and rely on capsid proteins for protection and host-cell attachment [9]. They are generally more resistant to environmental stressors and exhibit more stable antigenic properties [9]. Examples include adenoviruses, poliovirus, and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) [9].

Table 1: Structural and Functional Comparison of Enveloped and Non-enveloped Viruses

| Characteristic | Enveloped Viruses | Non-enveloped Viruses |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Structure | Lipid bilayer envelope | Protein capsid |

| Stability | Sensitive to heat, desiccation, detergents | Resistant to environmental stressors |

| Transmission | Close contact, bodily fluids, protected aerosols | Fomites, fecal-oral route, contaminated water |

| Antigenic Variation | High (e.g., HIV, Influenza) | Generally more stable |

| Entry Mechanisms | Endocytosis, fusion | Endocytosis, direct penetration |

| Examples | HIV, Influenza, SARS-CoV-2, Herpesvirus | Adenovirus, Poliovirus, Norovirus, AAV |

Molecular Determinants of Tropism

Primary Receptors and Attachment Factors

Viral receptors function as key regulators of host range, tissue tropism, and viral pathogenesis [11]. These molecules can be categorized into several classes based on their structure and function:

Sialylated Glycans: Many viruses utilize sialic acid (SA) derivatives as initial attachment points, particularly respiratory viruses like Influenza A virus (IAV) which recognizes 5-N-acetyl neuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) [11]. These interactions often represent low-affinity, high-avidity initial contacts that precede higher-affinity interactions with specific protein receptors [11].

Immunoglobulin Superfamily (IgSF) Members: These cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are frequently exploited by viruses for attachment and entry [11]. Examples include:

Integrins: Heterodimeric transmembrane receptors that mediate cell-extracellular matrix adhesion, utilized by viruses such as foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) and coxsackievirus B (CVB) [11].

Phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) Receptors: Recently recognized family of receptors that recognize phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells, which some viruses exploit for entry [11].

Table 2: Characterized Viral Receptors and Their Virus Interactions

| Virus | Primary Receptor | Receptor Class | Key Viral Protein | Tropism Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | ACE2 | IgSF | Spike (S) protein RBD | Broad tissue tropism (lung, intestine, heart, kidney) [14] |

| HIV-1 | CD4 | IgSF | gp120 | Targeting of CD4+ T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells [10] |

| Influenza A | Sialic acid | Carbohydrate | Hemagglutinin (HA) | Respiratory epithelial targeting [9] [11] |

| Rabies | Various neuronal receptors | Multiple | Glycoprotein G | Strong neuronal tropism, retrograde transport [9] |

| Hepatitis B | NTCP (sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide) | Transporter protein | PreS1 domain | Hepatocyte specificity [9] |

Co-receptors and Entry-Activating Proteases

Beyond primary receptors, viruses often require additional host factors for efficient entry. These include:

Chemokine Co-receptors: HIV-1 utilizes CCR5 or CXCR4 as essential co-receptors following CD4 binding [15] [10]. Co-receptor choice has significant implications for disease progression, with CCR5-tropic (R5) viruses predominating in early infection and CXCR4-tropic (X4) viruses emerging later and associated with accelerated CD4+ T-cell decline [15] [10].

Protease Systems: Many viruses require proteolytic activation of their entry proteins. SARS-CoV-2 utilizes multiple proteases including TMPRSS2, furin, and cathepsins for S protein priming and activation [16] [14]. The specific protease repertoire of host cells significantly influences tissue tropism and pathogenicity [16].

The requirement for specific co-receptor and protease combinations creates additional barriers for viral host range and contributes to tissue and species specificity [13].

Post-receptor Intracellular Factors

Even successful receptor engagement does not guarantee productive infection, as intracellular factors play crucial roles in tropism determination:

- Transcriptional Regulation: Cell-type specific transcription factors may be required for viral gene expression.

- Restriction Factors: Host proteins like APOBEC3G, TRIM5α, and tetherin can block viral replication in a cell-type specific manner [12].

- Host Machinery Compatibility: The availability of specific host factors for viral replication, protein synthesis, and virion assembly varies between cell types [9].

These post-entry factors explain why mere receptor expression does not always correlate with permissiveness to infection, as demonstrated by the resistance of macrophages to X4 HIV-1 variants despite expressing both CD4 and CXCR4 [10].

Experimental Methodologies for Tropism Determination

Coreceptor Tropism Assays for HIV-1

Determining HIV-1 co-receptor usage is clinically essential for assessing eligibility for CCR5 antagonist therapy [15]. Standardized protocols include:

Geno2pheno Algorithm: A bioinformatics approach that predicts co-receptor usage based on V3 loop sequence characteristics [15].

- Procedure: HIV-1 RNA is extracted from patient plasma, the envelope (env) gene is amplified by nested PCR, and the V3 region is sequenced [15].

- Analysis: Sequences are analyzed using the Geno2pheno algorithm with a false-positive rate (FPR) of 10% (current European guidelines) [15]. FPR >10% indicates CCR5-tropic virus; FPR ≤10% indicates CXCR4-tropic virus [15].

- Parameters: V3 loop net charge calculation [(R+K)-(D+E)] and N-linked glycosylation site analysis between amino acids 6-8 provide additional tropism indicators [15].

Cell-Based Fusion Assays: Functional tests using cell lines engineered to express CD4 and specific co-receptors (CCR5, CXCR4) to monitor viral entry and fusion events [10].

Primary Cell Validation: Confirmation using primary cells, including:

- CCR5 Δ32 PBMCs: Absent viral replication in PBMCs from CCR5 Δ32 homozygous individuals indicates CCR5 dependence [10].

- Receptor Antagonists: Specific coreceptor antagonists (e.g., AMD3100 for CXCR4) inhibit entry via cognate receptors [10].

Receptor Identification and Validation

Comprehensive receptor identification involves multiple complementary approaches:

CRISPR Screening: Genome-wide knockout screens identify essential receptors and host factors through negative selection [13].

Glycan Array Screening: High-throughput profiling of viral binding to diverse carbohydrate structures reveals SA receptor specificity and preferences [11].

Structural-Functional Analyses:

- X-ray Crystallography/Cryo-EM: Determine atomic-level virus-receptor interaction interfaces [14] [11].

- Surface Plasmon Resonance: Quantifies binding affinity and kinetics of virus-receptor interactions [11].

Pseudotyping Studies: Replacing viral envelope proteins with those from other viruses (e.g., VSV-G) to test receptor specificity and entry requirements [9] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Tropism Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Key Features | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geno2pheno Algorithm | Bioinformatics prediction of co-receptor usage | Web-based, uses V3 sequence with adjustable FPR | HIV-1 tropism determination for clinical assessment [15] |

| Vero Cells | Viral culture and vaccine production | Highly susceptible to multiple viruses, continuous cell line | Production of vaccines for polio, rabies, Japanese encephalitis [12] |

| MDCK Cells | Influenza virus propagation | canine kidney cells with appropriate sialic acid receptors | Influenza vaccine production, virus isolation [12] |

| CCR5 Δ32 PBMCs | Validation of CCR5 dependence | Cells from CCR5 Δ32 homozygous individuals | Confirm R5 HIV-1 tropism [10] |

| Receptor Antagonists (AMD3100, Maraviroc) | Functional tropism determination | Specific blockade of CXCR4 or CCR5 | Inhibit entry via specific co-receptors [10] |

| Pseudotyped Viruses | Safe study of entry mechanisms | VSV-G pseudotyped particles with target envelopes | Study entry of highly pathogenic viruses (Ebola, SARS-CoV-2) [11] |

| CRISPR Libraries | Genome-wide receptor screening | Identify essential host factors through negative selection | Discovery of novel receptors and restriction factors [13] |

Case Studies in Viral Tropism

SARS-CoV-2: Broad Tissue Tropism Through Multiple Receptors

SARS-CoV-2 demonstrates exceptionally broad tissue tropism, infecting respiratory, cardiac, renal, intestinal, and neurological tissues [16] [14]. This promiscuity stems from its ability to utilize multiple receptors and entry pathways:

ACE2 as Primary Receptor: The spike RBD binds the peptidase domain of ACE2 with high affinity, utilizing a bridge-shaped α1 helix interface with key residues (Q498, T500, N501) forming hydrogen bonds with ACE2 (Y41, Q42, K353, R357) [14].

Alternative Receptors: Neuropilin-1, AXL, and antibody-FcγR complexes provide additional entry routes, particularly in cells with low ACE2 expression [14].

Protease Activation Systems: Tissue-specific expression of TMPRSS2 (plasma membrane), furin (Golgi), and cathepsins (endosomes) enables spike protein priming in different cellular compartments [16] [14].

Receptor Polymorphisms and Variants: ACE2 polymorphisms and spike protein mutations (particularly in the RBD) influence viral affinity and tissue targeting, contributing to variant-specific pathogenicity [16].

HIV-1: Dynamic Co-receptor Usage and Disease Progression

HIV-1 tropism is primarily defined by chemokine co-receptor usage, which evolves throughout infection and significantly impacts pathogenesis:

CCR5-tropic (R5) Viruses: Predominate during early infection and establish new infections [15] [10]. Characterized by non-syncytium-inducing (NSI) phenotype in MT-2 cells and efficient infection of macrophages and CCR5+ memory T-cells [10].

CXCR4-tropic (X4) Viruses: Typically emerge during later stages in approximately 50% of infected individuals, associated with syncytium-inducing (SI) phenotype and accelerated CD4+ T-cell decline [10].

V3 Loop Determinants: The third variable region of gp120 contains critical tropism determinants:

- Net Charge: X4 viruses typically have higher V3 net charge (median 4.0 vs 3.0 for R5) [15].

- Glycosylation Patterns: Conserved N-linked glycosylation site between amino acids 6-8 in R5 viruses, often absent in X4 variants [15].

- Crown Motifs: GPGQ is the most prevalent motif in both R5 and X4 viruses across multiple genotypes [15].

Clinical Implications: CCR5 antagonists like maraviroc are only effective against R5 viruses, necessitating tropism testing before treatment [15]. The near-complete resistance to HIV-1 infection in CCR5 Δ32 homozygotes underscores the importance of CCR5 in transmission [10].

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Vaccine Design

Understanding molecular determinants of tropism enables innovative therapeutic approaches:

Receptor-Blocking Strategies: Monoclonal antibodies targeting virus-receptor interfaces (e.g., anti-ACE2 for SARS-CoV-2) [14], small molecule inhibitors (e.g., maraviroc for CCR5) [15], and decoy receptors [13].

Engineered Tropism for Gene Therapy: Viral vectors (particularly AAVs) are engineered with modified tropism for targeted gene delivery using rational design, directed evolution, and machine learning approaches [9].

Broad-Spectrum Antivirals: Targeting common viral receptors (sialic acids, integrins, IgSF members) or essential host factors (TMPRSS2, furin) offers potential for broad-spectrum activity [11].

Vaccine Development: Cell culture-based vaccine production requires adaptation of vaccine strains to cell substrates (Vero, MDCK) [12]. Understanding receptor usage enables development of broadly permissive cell lines for vaccine manufacturing against multiple viruses [12].

Molecular determinants of tropism—including primary receptors, co-receptors, and host factors—represent fundamental regulators of viral pathogenesis, host range, and transmission dynamics. The intricate interplay between viral attachment proteins and host cell molecules governs tissue specificity, disease progression, and cross-species transmission potential. Advanced methodologies for tropism determination, from bioinformatic predictions to structural analyses and functional assays, continue to reveal new insights into these critical interactions.

This understanding directly informs therapeutic development, from receptor-blocking strategies and entry inhibitors to engineered vectors for gene therapy. As viral threats continue to emerge, particularly those with zoonotic potential, comprehensive knowledge of tropism determinants will remain essential for predicting spillover risk, developing targeted interventions, and designing effective vaccines within a One Health framework. Future research should focus on integrative mapping of receptor networks, comparative analyses across viral families, and translation of these insights into broad-spectrum therapeutic strategies.

The concept of portals of entry and exit is fundamental to understanding viral epidemiology and pathogenesis. These portals represent the specific anatomical sites through which viruses enter a susceptible host and subsequently exit to enable transmission to new hosts [17] [18]. The specific portals a virus utilizes are intrinsically linked to its host range—the diversity of species and cell types it can infect—and its transmission modes, which together determine its epidemic potential and evolutionary trajectory [19] [8]. Viruses have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to exploit specific bodily surfaces, and their ability to jump between species often depends on acquiring mutations that allow them to utilize these portals in new hosts [20].

The respiratory, gastrointestinal, genital, and vector-borne routes represent four major portal systems with distinct biological characteristics. Respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts present mucosal surfaces directly exposed to the environment, while the genital tract offers a more protected environment with different immunological properties [17]. Vector-borne transmission bypasses the body's external barriers entirely, using arthropods to deliver virus directly into the skin or bloodstream [21]. Understanding the molecular and evolutionary signatures associated with each portal is crucial for predicting emerging viral threats and designing targeted interventions [8].

This technical guide examines the core principles of these four portal systems, focusing on their roles in viral host range determination and transmission dynamics. We integrate quantitative data on representative viruses, experimental methodologies for studying portal-specific mechanisms, and computational approaches for predicting transmission routes based on viral genomic features.

Respiratory Route

Anatomical and Physiological Features

The respiratory tract presents a large epithelial surface area directly exposed to the environment, making it one of the most common routes for viral entry and exit [17]. An average human adult inhales approximately 600 liters of air hourly, creating numerous opportunities for virus-laden particles to initiate infection [17]. The respiratory system is anatomically and functionally divided into the upper respiratory tract (nasal cavity, pharynx, larynx) and lower respiratory tract (trachea, bronchi, lungs), with different cell types exhibiting varying susceptibility to viral infections.

The portal of exit for respiratory viruses typically occurs through the same anatomical structures used for entry. Viruses replicate in respiratory epithelial cells and are expelled via respiratory secretions during breathing, coughing, sneezing, or talking [17]. Droplet spread occurs when larger respiratory droplets (>5 μm) are projected short distances and quickly settle, while airborne transmission involves smaller droplet nuclei (<5 μm) that remain suspended in air for extended periods and can travel considerable distances [22]. This distinction has important implications for control measures, as airborne viruses like measles require more stringent environmental controls than those primarily spread through droplets [22].

Representative Viruses and Host Range Implications

Table 1: Representative Respiratory Viruses and Their Characteristics

| Virus | Family | Primary Host(s) | Host Range | Portal of Exit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus | Orthomyxoviridae | Birds, humans, swine | Broad (generalist) | Respiratory secretions |

| Rhinoviruses | Picornaviridae | Humans | Narrow (specialist) | Respiratory secretions |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Coronaviridae | Humans, potential animal reservoirs | Broad | Respiratory secretions |

| Measles virus | Paramyxoviridae | Humans | Narrow | Respiratory secretions, urine |

Influenza A virus exemplifies a respiratory virus with a broad host range, capable of infecting birds, humans, swine, and other mammals [19]. Its ability to utilize sialic acid receptors with different linkages in various species facilitates cross-species transmission. The virus exits infected hosts through respiratory secretions and can be transmitted through both droplet and aerosol routes [17]. In contrast, measles virus represents a specialist pathogen with humans as its only known natural host, exiting through respiratory secretions and requiring close contact for transmission [22].

The host range of respiratory viruses is determined by receptor distribution across species, environmental stability of viral particles, and compatibility with host innate immune responses in the respiratory tract. Generalist respiratory viruses like Influenza A often have segmented genomes that allow reassortment, facilitating rapid adaptation to new hosts [19]. Specialist viruses typically establish long-term relationships with their primary host, often leading to lifelong immunity after infection [17].

Research Models and Methodologies

Table 2: Experimental Models for Respiratory Virus Research

| Model System | Applications | Key Readouts |

|---|---|---|

| Human airway epithelial (HAE) cultures | Study viral entry, replication kinetics, innate immune responses | Viral titer, cytokine production, transcriptomics |

| Ferret model | Influenza transmission studies | Transmission efficiency, clinical signs, shedding titers |

| Mouse models (including humanized mice) | Pathogenesis studies, therapeutic testing | Lung viral load, histopathology, immune cell infiltration |

| Organoid cultures | Cell-type specific tropism studies | Single-cell RNA sequencing, immunofluorescence |

Air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures of human airway epithelial cells represent a sophisticated in vitro model that recapitulates the pseudostratified mucociliary epithelium of the human respiratory tract. These cultures allow researchers to study the early events of respiratory viral infection, including ciliary function, mucus production, and innate immune responses. For transmission studies, the ferret model remains the gold standard for influenza research due to similar receptor distribution and clinical disease presentation as humans.

Gastrointestinal Route

Anatomical and Physiological Features

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract presents a harsh environment for viral survival, with extreme pH variations, digestive enzymes, and bile salts that inactivate many enveloped viruses [17]. Successful enteric viruses must resist these conditions to reach susceptible cells in the intestinal epithelium. The "fecal-oral" route characterizes the transmission cycle of GI viruses: they exit an infected host in feces, contaminate water or food, and enter a new host through the mouth to establish infection in the GI tract [22] [17].

The portal of entry for GI viruses is typically the oral cavity, with primary replication occurring in the intestinal epithelium. Peyer's patches in the small intestine represent important lymphoid tissues where some viruses initiate immune responses. The portal of exit is through fecal shedding, which can continue for extended periods even after symptoms resolve, facilitating silent transmission [17]. Effective transmission requires environmental stability, as viruses must persist in water, food, or on fomites until encountering a new host.

Representative Viruses and Host Range Implications

Table 3: Representative Gastrointestinal Viruses and Their Characteristics

| Virus | Family | Primary Host(s) | Host Range | Environmental Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotavirus | Reoviridae | Humans, animals | Moderate (species-specific strains) | High (resists degradation) |

| Norovirus | Caliciviridae | Humans | Narrow (specialist) | High |

| Hepatitis A virus | Picornaviridae | Humans | Narrow | High |

| Enteroviruses | Picornaviridae | Humans | Narrow to Moderate | Moderate |

Norovirus exemplifies a specialist GI virus with humans as the primary host, causing widespread outbreaks through fecal-oral transmission. Its environmental stability and low infectious dose contribute to its persistence in populations. In contrast, rotavirus exists in multiple species-specific strains, with some evidence of zoonotic transmission potential [17]. Hepatitis A virus demonstrates the importance of inapparent carriers in transmission, with only 10% of infected children showing jaundice despite half being contagious [18].

The host range of enteric viruses is constrained by receptor compatibility across species, resistance to host-specific digestive processes, and temperature optimization for replication. Successful GI viruses often have non-enveloped structures that confer environmental stability, allowing persistence in water and soil [17]. This stability expands their transmission potential beyond direct host-to-host contact.

Genital Route

Anatomical and Physiological Features

The genital tract represents a protected portal of entry with distinct immunological properties compared to other mucosal surfaces. Viral entry typically occurs through microtears or direct infection of mucosal epithelium during sexual contact. Unlike respiratory and GI tracts, the genital tract is not continuously exposed to environmental pathogens, which may influence local immune surveillance [17].

The portal of exit for genital viruses is primarily through genital secretions and semen, though some viruses can also be transmitted through saliva, blood, or from mother to child [17]. This route often requires intimate contact for transmission, which can limit spread compared to respiratory or fecal-oral routes but facilitates establishment of persistent infections in specific populations.

Representative Viruses and Host Range Implications

Table 4: Representative Genital Viruses and Their Characteristics

| Virus | Family | Primary Host(s) | Host Range | Additional Transmission Routes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) | Retroviridae | Humans | Narrow | Blood, perinatal |

| Herpes Simplex Virus type 2 (HSV-2) | Herpesviridae | Humans | Narrow | Perinatal, oral |

| Human Papillomavirus (HPV) | Papillomaviridae | Humans | Narrow | Skin-to-skin contact |

| Hepatitis B virus | Hepadnaviridae | Humans | Narrow | Blood, perinatal |

HIV represents a classic example of a virus that primarily utilizes the genital route, though its host range is restricted to humans despite origins in non-human primates [20]. The narrow host range of most genital viruses reflects specialized adaptations to human-specific receptors and cellular factors. HPV demonstrates how genital viruses can exploit epithelial differentiation programs, with certain high-risk types causing cervical cancer through persistence and cellular transformation [17].

Genital transmission often involves complex host-virus relationships with periods of latency or persistence, as seen with HSV-2 and HIV. This persistence allows viruses to overcome the limitations of requiring intimate contact for transmission by maintaining infectious reservoirs within populations. Mother-to-child transmission represents an important secondary route for several genital viruses, including HIV and HBV, enabling vertical perpetuation in addition to horizontal spread [17].

Vector-Borne Route

Ecological and Molecular Features

Vector-borne transmission represents a complex tripartite relationship between virus, vector, and vertebrate host [21]. Unlike direct transmission routes, vector-borne viruses must overcome barriers in both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts, requiring adaptations for replication in phylogenetically distant species [20]. The portal of entry is typically the skin, where virus is deposited along with vector saliva during blood feeding [21]. The portal of exit requires viremia sufficient to infect subsequent vectors during their blood meals.

The vector-host-pathogen interface has emerged as a critical frontier in understanding mosquito-borne viral diseases [21]. Mosquito saliva contains numerous pharmacologically active compounds that modulate host immune responses, enhancing viral replication and dissemination [21]. At the bite site, an influx of immune cells occurs, many of which are permissive to infection, creating an optimal environment for initial viral amplification before systemic spread.

Representative Viruses and Host Range Implications

Table 5: Representative Vector-Borne Viruses and Their Characteristics

| Virus | Family | Primary Vector(s) | Reservoir Hosts | Human Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dengue virus | Flaviviridae | Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus | Humans, non-human primates | Amplifying host |

| West Nile virus | Flaviviridae | Culex species | Birds | Incidental/dead-end host |

| Zika virus | Flaviviridae | Aedes species | Humans, non-human primates | Amplifying host |

| Japanese Encephalitis virus | Flaviviridae | Culex species | Birds, pigs | Incidental host |

Dengue virus exemplifies a vector-borne virus that has adapted to use humans as its primary reservoir host, transmitted mainly by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in urban settings [20]. This close association with human habitats has enabled its widespread distribution in tropical and subtropical regions. In contrast, West Nile virus maintains an enzootic cycle primarily between birds and Culex mosquitoes, with humans and other mammals serving as incidental "dead-end" hosts that do not contribute to transmission cycles [20].

The host range of vector-borne viruses is constrained by multiple factors, including vector feeding preferences, viral replication efficiency in both vector and host, and environmental temperature [23]. Some viruses like West Nile virus demonstrate remarkable host breadth, infecting 49 species of mosquitoes and ticks, and 225 species of birds, in addition to various mammals [20]. This generalist strategy enhances geographic spread and persistence in diverse ecosystems.

Advanced Research Methodologies

Computational Prediction of Transmission Routes

Recent advances in machine learning have enabled computational prediction of viral transmission routes based on genomic features [8]. Wardeh et al. (2024) developed a framework that integrates viral sequence features, host association data, and ecological variables to predict transmission routes with high accuracy (ROC-AUC = 0.991 across all routes) [8]. Their approach utilizes LightGBM classifier ensembles trained on 24,953 virus-host associations with 81 defined transmission routes.

Table 6: Key Feature Categories for Predicting Viral Transmission Routes

| Feature Category | Examples | Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic features | Codon usage bias, nucleotide composition, GC content | High for distinguishing vector-borne vs. direct transmission |

| Structural features | Capsid symmetry, envelope presence, genome organization | Moderate to high for respiratory and GI routes |

| Ecological features | Host taxonomy, climate associations, vector distributions | Critical for vector-borne and zoonotic routes |

| Evolutionary features | Evolutionary rates, recombination frequency, selection pressure | High for predicting host switching potential |

This computational approach identified specific evolutionary signatures associated with different transmission routes. For instance, vector-borne viruses show distinct codon usage adaptations reflecting their dual-host life cycle, while respiratory viruses exhibit features optimizing for environmental stability in aerosol droplets [8]. These predictive models can guide laboratory investigations by prioritizing likely transmission routes for newly discovered viruses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 7: Key Research Reagents for Studying Viral Portals of Entry

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Human airway epithelial (HAE) cultures at ALI | Respiratory virus studies | Mimics human respiratory epithelium with functional cilia and mucus production |

| Caco-2 cell line | Gastrointestinal virus studies | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma line that differentiates into enterocyte-like cells |

| Huh-7 cell line | Hepatitis virus studies | Human hepatoma line permissive for multiple hepatitis viruses |

| Vero cells (African green monkey kidney) | Viral isolation and propagation | Interferon-deficient allowing wide viral tropism |

| Aedes albopictus C6/36 cells | Arbovirus propagation | Mosquito cell line supporting high-titer arbovirus replication |

| Reverse genetics systems | Viral pathogenesis studies | Enables introduction of specific mutations to study portal determinants |

| Neutralizing antibodies | Portal entry blockade studies | Maps receptor usage and tests intervention strategies |

| Organoid cultures | Cell-type specific tropism | Recapitulates tissue architecture for portal-specific studies |

Experimental Workflow for Portal Determination

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates a comprehensive experimental workflow for determining viral portals of entry and exit:

Diagram Title: Viral Portal Determination Workflow

This integrated workflow begins with viral isolation and genomic sequencing, enabling computational prediction of potential transmission routes [8]. In vitro models including cell lines and organoids help identify permissive cell types and tissue tropisms [21]. Animal models remain essential for studying pathogenesis and transmission efficiency, particularly for respiratory and vector-borne viruses [20]. Mechanistic studies focus on receptor usage, immune evasion strategies, and host adaptations [17]. Promising interventions are tested against portal-specific transmission, with data integration refining predictive models for future outbreaks.

The respiratory, gastrointestinal, genital, and vector-borne routes represent distinct ecological niches that viruses have exploited through specialized adaptations. Each portal presents unique challenges and opportunities for viral entry, replication, and exit, ultimately shaping host range and transmission dynamics. Respiratory viruses often evolve generalist strategies with broad host ranges, while genital viruses typically specialize with narrow host ranges. Gastrointestinal viruses balance environmental stability with host specificity, while vector-borne viruses master the complex tripartite relationship between vector, reservoir host, and incidental host.

Understanding the molecular signatures associated with each portal provides crucial insights for predicting emerging viral threats and designing targeted interventions. The integration of computational approaches with traditional experimental models offers a powerful framework for rapidly characterizing new pathogens and their transmission potential. As climate change, urbanization, and global travel alter the landscape of infectious diseases [24] [23], research on viral portals of entry will remain essential for pandemic preparedness and response.

Future directions include developing more sophisticated organoid models that recapitulate the complex architecture of portal tissues, advancing single-cell technologies to understand cellular tropism at unprecedented resolution, and refining machine learning algorithms to predict host switching events based on portal-specific adaptations. By focusing on the fundamental biology of viral portals of entry and exit, researchers can better anticipate and mitigate the next pandemic threat.

Viral transmission is a complex process governed by the intricate interplay between structural stability and genetic evolution. This whitepaper examines how structural constraints on viral envelopes and genomes determine transmission efficiency and host range breadth. Through detailed analysis of measles virus as a paradigm of high genetic stability and comparison with other viral families, we identify key molecular mechanisms that limit evolutionary rates while facilitating efficient spread. We present quantitative data on mutation rates, structural stabilization parameters, and experimental approaches for investigating these constraints. The findings provide a framework for understanding how structural virology principles inform transmission dynamics, with significant implications for antiviral development and pandemic preparedness.

Viral transmission between hosts represents the critical bottleneck in pathogen ecology and evolution. Successfully navigating this bottleneck requires virions to maintain structural integrity while retaining the capacity to initiate new infections. From a structural virology perspective, virions are dynamic nucleoprotein assemblies that must balance robustness for environmental stability with flexibility for host cell entry [25]. This balance is particularly governed by the structural constraints imposed by envelope proteins and genome organization.

The genetic architecture of viruses creates fundamental constraints on evolutionary potential. RNA viruses typically exhibit higher mutation rates than DNA viruses, yet notable exceptions exist that demonstrate exceptionally high genetic stability despite RNA genomes. Measles virus (MeV) represents a paradigmatic case of such constraints, with remarkably low evolutionary rates despite its RNA genome [26]. Similarly, coronaviruses employ proofreading mechanisms that reduce mutation rates, facilitating their success as cross-species pathogens.

Within the context of viral host range research, understanding these structural constraints provides critical insights into transmission barriers and spillover potential. This technical guide examines the molecular basis of these constraints, presents experimental approaches for their investigation, and discusses implications for therapeutic intervention.

Structural Constraints on Viral Envelopes

Viral envelope proteins mediate the critical initial steps of host cell recognition and entry, making their structural features fundamental to transmission efficiency. The envelope glycoproteins must maintain conserved functional domains while potentially accommodating sequence variation that enables immune evasion.

Measles Virus: A Case Study in Envelope Stability

Measles virus exhibits exceptional antigenic stability with only a single serotype identified despite genetic diversity encompassing 24 genotypes [26]. This paradox of genetic variation without antigenic drift reflects strong structural constraints on its envelope proteins, particularly the hemagglutinin (H) and fusion (F) proteins.

Molecular Basis of Envelope Constraint in MeV:

- The H protein contains five conserved neutralizing epitopes maintained across genotypes

- Antibodies targeting two specific epitopes effectively neutralize all tested genotypes

- Structural analyses indicate these epitopes are involved in critical functional interactions: one mediates binding to the host receptor SLAM, while the other interferes with H-F protein interaction

- Escape mutations against monoclonal antibodies remain susceptible to polyclonal serum neutralization, suggesting MeV must simultaneously mutate multiple epitopes to evade immunity [26]

These structural constraints appear biologically essential for maintaining receptor binding capability and membrane fusion machinery. The functional conservation of these domains limits antigenic drift despite genomic variation, creating a transmission advantage through maintained host range but potentially increasing susceptibility to population immunity.

Comparative Envelope Architectures

Table 1: Structural Features of Viral Envelope Proteins and Their Transmission Implications

| Virus Family | Envelope Protein Features | Structural Constraints | Impact on Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paramyxoviridae (e.g., Measles) | Homotetrameric fusion protein (F) and receptor-binding protein (H) | Strong functional conservation of receptor-binding and fusion domains | Single serotype; lifelong immunity; requires multiple simultaneous mutations for immune escape |

| Coronaviridae (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) | Trimeric spike glycoprotein with S1/S2 subunits | Receptor-binding domain (RBD) flexibility balanced with maintenance of ACE2 binding | Potential for recombination events; variant emergence with altered transmissibility |

| Retroviridae (e.g., HIV-1) | Heterotrimeric envelope complex (gp120/gp41) | High glycosylation masking variable loops; conformational masking of conserved domains | Extreme antigenic diversity within hosts; complex transmission dynamics |

| Orthomyxoviridae (e.g., Influenza) | Hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) | Conservation of sialic acid binding site and fusion peptide in HA | Antigenic drift and shift necessitate vaccine updates; zoonotic transmission potential |

The envelope constraints directly influence transmission modes by determining environmental stability and host cell tropism. Viruses with highly constrained envelope architectures typically exhibit more stable transmission patterns but may be more vulnerable to vaccination strategies that target conserved epitopes.

Genomic Architecture and Evolutionary Constraints

Genome organization imposes fundamental constraints on evolutionary potential through mutation rates, recombination potential, and structural genomic features.

Exceptional Genetic Stability in Measles Virus

MeV demonstrates remarkably high genetic stability both in laboratory settings and natural circulation. Quantitative analyses reveal:

Table 2: Evolutionary Rate Comparison Between Measles Virus and Other RNA Viruses

| Virus | Genome Type | Substitution Rate (subs/base/year) | Genetic Stability Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measles virus | Negative-sense RNA | 4-5 × 10⁻⁴ | High fidelity polymerase; structural constraints on envelope proteins; limited genomic plasticity |

| HIV-1 | Positive-sense RNA | >1.6 × 10⁻³ | Error-prone reverse transcriptase; rapid turnover; immune pressure |

| Influenza A virus | Negative-sense RNA | ~2.0 × 10⁻³ | Segment reassortment; antigenic drift; animal reservoirs |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Positive-sense RNA | ~1.0 × 10⁻³ | Proofreading exonucleases; recombination potential |

| Foot-and-mouth disease | Positive-sense RNA | >1.6 × 10⁻³ | Error-prone polymerase; quasispecies dynamics |

Molecular analyses indicate the MeV genome contains surprisingly few regions tolerant of rapid mutation. The most variable region, the carboxy-terminal 450 nucleotides of the nucleocapsid gene (N-450), shows remarkable stability even during extended in vitro passaging in different cell types [26]. This stability persists despite the error-prone nature of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases generally.

Mechanisms of Genomic Constraint

Several interconnected mechanisms maintain genomic stability in constrained viruses:

Polymerase Fidelity: While paramyxoviruses encode error-prone RNA polymerases, MeV may employ additional mechanisms to enhance replication fidelity, though the exact mechanisms remain incompletely characterized.

Structural RNA Elements: Secondary and tertiary RNA structures throughout the genome may constrain evolutionary potential by creating functional demands that limit sequence variability.

Genome Packaging Requirements: The nucleocapsid protein packaging mechanism creates structural demands that limit variability. For SARS-CoV-2, the nucleocapsid protein exhibits intrinsic disorder that becomes structured upon RNA binding, creating specific constraints [27].

Protein Structural Demands: Multifunctional proteins experience stronger evolutionary constraints due to competing structural demands. In MeV, the phosphoprotein (P) encodes multiple overlapping reading frames (P, C, and V proteins), creating constraints that limit variability.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Structural Constraints

Understanding viral structural constraints requires multidisciplinary approaches spanning structural biology, genetics, and evolutionary analysis.

Structural Stabilization Protocols

Stabilization of Intrinsically Disordered Viral Proteins: The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein represents a challenging structural target due to intrinsic disorder regions (IDRs) comprising approximately 45% of the protein sequence. Recent methodological advances enable stabilization through:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Virology

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilization Agents | Engineered symmetric RNA sequences; viral genome-derived RNA fragments | Promote formation of structurally homogeneous complexes; stabilize intrinsically disordered regions |

| Structural Biology Tools | Domain-specific monoclonal antibodies; cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS); cryo-EM grids | Validate spatial arrangements; stabilize transient conformations; high-resolution structure determination |

| Biophysical Characterization | Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC); analytical ultracentrifugation; surface plasmon resonance | Assess thermal stability; determine oligomerization states; measure binding affinities |

| Cell Culture Systems | SLAM-expressing Vero cells; primary human airway epithelial cultures | Model relevant entry pathways; study tissue-specific transmission barriers |

Protocol: RNA-Mediated Stabilization of Nucleocapsid Proteins

- RNA Identification: Screen viral genome fragments for binding affinity using EMSA or SPR

- RNA Engineering: Design symmetric RNA sequences based on natural high-affinity binding sites

- Complex Formation: Incubate nucleocapsid protein with engineered RNA at 4:1 molar ratio in low-salt buffer

- Complex Purification: Separate stabilized complexes using size exclusion chromatography

- Validation: Verify structural homogeneity via negative stain EM and cross-linking mass spectrometry [27]

This approach has successfully stabilized SARS-CoV-2 N protein dimers, enabling structural characterization of this fundamental building block of viral capsid assembly.

Genetic Stability Assessment

Protocol: Quantifying Viral Evolutionary Rates

- Long-Term Passage: Serial passage in relevant cell culture systems (>50 passages)

- Sampling Strategy: Collect viral supernatant at regular intervals (every 5-10 passages)

- Sequence Analysis: Perform whole-genome sequencing with sufficient depth (>1000x coverage)

- Variant Calling: Identify fixed mutations and quantify minority variants

- Rate Calculation: Calculate substitution rates using molecular clock models [26]

For measles virus, this approach has demonstrated near-complete sequence identity after extensive passaging, with only single nucleotide changes observed between working stocks with divergent passage histories.

Visualization of Structural Constraint Mechanisms

The diagrams below illustrate key concepts and experimental approaches for investigating structural constraints in viral transmission.

Measles Virus Envelope Protein Constraints

MeV Envelope Constraint Mechanism This diagram illustrates how functional constraints on measles virus envelope proteins maintain antigenic stability. The hemagglutinin protein contains both highly conserved epitopes essential for receptor binding and membrane fusion, alongside more variable regions. The structural demands of these essential functions prevent antigenic drift and maintain a single serotype despite genetic diversity.

Genetic Stability Research Workflow

Genetic Stability Assessment Workflow This workflow outlines the experimental approach for quantifying viral genetic stability. The process begins with virus isolation followed by systematic in vitro passaging to simulate natural evolution. Regular whole-genome sequencing enables comprehensive variant analysis, ultimately allowing calculation of evolutionary rates using molecular clock models.

Implications for Viral Host Range and Transmission Modes

Structural constraints directly influence viral emergence potential and transmission dynamics through several mechanisms:

Host Range Determinants

The strength of structural constraints on receptor-binding domains correlates with host range breadth. MeV's strong constraint on its SLAM-binding domain limits its host range to humans and non-human primates, while influenza's more flexible receptor-binding site enables zoonotic transmission across species barriers.

Coronaviruses demonstrate intermediate constraint patterns, with conserved functional domains in the receptor-binding motif allowing some variability in specific residues that modulate host specificity. This creates the potential for host switching while maintaining efficient human-to-human transmission once established.

Transmission Efficiency Trade-Offs

Structural constraints create evolutionary trade-offs between transmission efficiency and immune evasion:

Highly constrained viruses like MeV exhibit stable transmission patterns with well-defined epidemiological characteristics, including critical community sizes for persistence and predictable age distributions of infection.

Less constrained viruses like influenza show more complex transmission dynamics with frequent epidemic and pandemic spread driven by antigenic variation, but with less predictable patterns.

Intervention Implications

The nature of structural constraints informs vaccine and therapeutic design:

- Viruses with high envelope constraint are vulnerable to vaccines targeting conserved epitopes

- Viruses with low genetic stability require therapeutic approaches targeting essential enzymatic functions with high genetic barriers to resistance

- Understanding nucleocapsid stabilization mechanisms may enable broad-spectrum antiviral approaches targeting genome packaging across virus families

Structural constraints on viral envelopes and genomes represent fundamental determinants of transmission efficiency and host range. The exceptional stability of measles virus demonstrates how strong functional constraints can maintain transmission efficiency despite limited evolutionary potential. Conversely, viruses with greater structural flexibility may achieve broader host ranges at the cost of transmission stability.

Experimental approaches combining structural biology, evolutionary analysis, and biophysical characterization provide powerful tools for investigating these constraints. The resulting insights create opportunities for novel intervention strategies that exploit structural vulnerabilities in viral transmission machinery.

Future research should focus on comparative analyses across virus families to identify general principles of structural constraint and their relationship to emergence potential. Such efforts will enhance pandemic preparedness by enabling prediction of transmission dynamics for novel pathogens based on structural features.

The classical paradigm of viruses as purely parasitic entities is being fundamentally redefined by emerging research that reveals a complex spectrum of interactions, including commensal and mutualistic relationships. This whitepaper synthesizes current evidence from eukaryotic and prokaryotic systems demonstrating that viral persistence involves sophisticated co-evolutionary adaptations benefiting both virus and host. We examine the L-A virus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae providing host stress resilience, the temporal mutualism of varicella-zoster virus in humans, and metabolic dependency in bacteriophage infections. Through integrated analysis of genomic screens, evolutionary modeling, and molecular mechanisms, we establish a new framework for understanding virus-host relationships with significant implications for antiviral therapeutic development and viral ecology research.

The conceptualization of viruses has traditionally been dominated by the parasite model, focusing on pathogenicity and host damage. However, growing evidence from diverse biological systems indicates this view is incomplete. The virus-host interaction spectrum encompasses relationships ranging from parasitism to commensalism and mutualism, often dynamically shifting across time and context. This paradigm shift recognizes that viral persistence—a fundamental aspect of virology—frequently involves sophisticated co-evolutionary adaptations that can provide selective advantages to host organisms [28] [29] [30].

The emerging framework has profound implications for understanding viral ecology, evolution, and therapeutic interventions. Rather than representing biological accidents or pure conflicts, many persistent viral infections reflect finely balanced relationships shaped by millions of years of co-evolution. This whitepaper examines the mechanistic bases and evolutionary drivers across the virus-host interaction spectrum, with particular focus on newly characterized mutualistic relationships and their relevance to viral host range and transmission mode research.

Mutualism in Eukaryotic Systems: From Yeast to Humans

The L-A Virus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A Case of Functional Mutualism

Recent genome-wide screening of Saccharomyces cerevisiae has revealed a striking mutualistic relationship with the L-A double-stranded RNA virus. An unbiased screen covering approximately 93% of annotated yeast genes identified 96 host factors required for efficient L-A maintenance, spanning diverse biological processes far beyond previously known factors [28].

Key Experimental Findings:

- Genomic Screening Protocol: Systematic analysis of yeast deletion and temperature-sensitive mutant collections using a standardized hot phenol/chloroform RNA extraction protocol followed by agarose gel electrophoresis detection of L-A dsRNA. Candidates underwent five rigorous screening rounds to eliminate false positives [28].

- Transcriptomic Profiling: RNA sequencing revealed that L-A presence significantly alters host stress-response gene expression patterns, priming the yeast for environmental challenges [28].

- Competitive Fitness Assays: Flow-cytometry-based competitions between isogenic L-A-free (L-A-), L-A-containing (L-A+), and L-A-overexpressing (L-A++) strains against a reference strain expressing fluorescent markers (TDH2::GFP and ADK1::mCherry) demonstrated that L-A enhances host resilience under multiple stress conditions [28].

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of L-A Virus Effect on Yeast Host Fitness

| Stress Condition | Competitive Index (L-A+ vs L-A-) | P-value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative stress | 1.47 | <0.01 | Large |

| Thermal stress | 1.32 | <0.05 | Medium |

| Osmotic stress | 1.28 | <0.05 | Medium |

| Nutrient limitation | 1.41 | <0.01 | Large |

This research demonstrates that the L-A virus, traditionally considered a persistent parasite, actually provides tangible benefits to its host under suboptimal conditions, explaining its widespread persistence in laboratory yeast strains without apparent cost [28].

Temporal Mutualism in Varicella-Zoster Virus: A Game-Theoretical Framework

The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) exemplifies how viral strategies can shift across the host lifespan in a temporally partitioned evolutionarily stable strategy (TP-ESS). Research proposes an "immunosensor hypothesis" where VZV latency within sensory ganglia contributes to host immune surveillance while ensuring viral persistence [29].

Three-Phase Model of VZV-Host Interaction:

- Childhood Replication Phase: Aggressive replication and transmission optimized for spread in immunologically naive populations.

- Immunomodulatory Latency Phase: Active maintenance through continuous immune engagement rather than quiescence, characterized by VLT transcripts and immune cell infiltration in sensory ganglia.

- Late-Life Reactivation Phase: Strategic reactivation during immunosenescence enabling intergenerational transmission [29].

Table 2: Temporal Characteristics of VZV-Host Relationship

| Interaction Phase | Host Age/Status | Viral Strategy | Host Outcome | Population Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary infection | Childhood | Lytic replication | Varicella | Herd immunity |

| Latency maintenance | Immune competence | Immunomodulation | Continuous surveillance | Niche persistence |

| Reactivation | Immunosenescence | Controlled reactivation | Herpes zoster | Intergenerational spread |

This triphasic relationship represents a sophisticated co-evolutionary adaptation where both host and virus derive benefits: the host maintains activated immune surveillance, while the virus achieves long-term persistence and periodic transmission opportunities [29].

Prokaryotic Systems: Metabolic Dependencies and Infection Commitments

Host Metabolic State Determines Viral Infection Outcomes

Groundbreaking research in bacteriophage systems reveals that viral commitment to infection depends critically on host metabolic state, not merely structural compatibility between viral ligands and host receptors. A systematic study of five Escherichia coli phages representing diverse life cycles and entry pathways demonstrated that four showed significantly reduced adsorption under energy-limited conditions [31].

Key Experimental Protocol:

- Phage Selection: Five E. coli phages with different entry mechanisms (LamB and FhuA receptors, bacterial pilus, Tsx porin).

- Metabolic Manipulation: Comparison of energy-competent (glucose-supplemented) versus energy-depleted conditions.

- Adsorption Quantification: Measurement of adsorption rate constant (η) under standardized conditions using titering of free viral particles in post-cellular supernatant compared to resistant hosts and buffer controls [31].

Findings and Implications: The correlation between baseline adsorption rates and metabolic sensitivity suggests a viral strategy to avoid non-productive infections under unfavorable host conditions. Phages with stronger binding affinity were less sensitive to host metabolic state, indicating an evolutionary trade-off between infection commitment and metabolic opportunism [31].

Diagram 1: Two-Step Phage Adsorption Model. This diagram illustrates the metabolic dependence of viral commitment to infection, where reversible attachment precedes irreversible binding only under favorable host conditions.

Evolutionary Frameworks and Theoretical Models

Game-Theoretical Analysis of Virus-Host Coevolution

The application of game theory to virus-host interactions provides a mathematical framework for understanding the evolutionary stability of seemingly paradoxical relationships. The VZV-human system has been modeled as a temporally partitioned evolutionarily stable strategy (TP-ESS) with distinct phases representing different strategic equilibria [29].

Strategic Options and Payoff Matrix:

- Host Strategies: Maintain Immune Surveillance (S) versus Reduce Immune Investment (¬S)

- Viral Strategies: Maintain Latency (L) versus Reactivate (¬L)

The equilibrium emerges from fitness payoffs that vary across host lifespan stages, creating a dynamic where neither player benefits from unilateral deviation from the strategy. This framework explains why high virulence during primary infection can coexist with long periods of asymptomatic latency and controlled reactivation [29].

Ecological Analogies and Their Limitations

Traditional ecological classifications of symbiotic relationships require modification when applied to viruses:

- Commensalism: Explains silent persistence but cannot account for reactivation pathology.

- Parasitism: Explains host damage but is inconsistent with low mutation rates and rare reactivation.

- Temporal Mutualism: Resolves these contradictions by recognizing time-partitioned benefits [29].

Methodologies for Studying Virus-Host Interactions

Genomic Screening Approaches

The identification of host factors involved in viral persistence has been revolutionized by systematic genetic approaches. The L-A virus screen employed both non-essential gene knockout (YKO) strains and temperature-sensitive (ts) mutant collections, with rigorous validation through multiple rounds of screening [28].

Essential Experimental Protocols:

Genome-wide Yeast Screening Protocol:

- Culture YKO and ts strains in 96-deep-well plates for 72 hours at 28°C

- Extract total RNA using standardized hot phenol/chloroform procedure

- Separate L-A dsRNA via 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis

- Quantify band intensities using ImageJ normalized to 18S rRNA

- Validate candidates through five sequential screening rounds

- Confirm via RT-qPCR with ACT1 normalization and Western blot using anti-Gag antibodies [28]

Temperature-Sensitive Mutant Screening:

- Grow ts mutants to saturation at permissive temperature (22°C)

- Seed equal cell numbers into fresh cultures and grow to mid-log phase

- Shift one culture to restrictive temperature (37°C) for 10 hours

- Maintain control at 22°C for same duration

- Harvest equal cell numbers for RNA isolation and analysis [28]

Competitive Fitness Assays

Quantifying the fitness consequences of viral persistence requires carefully controlled competition experiments:

Flow-Cytometry-Based Fitness Protocol:

- Engineer reference strain expressing constitutive fluorescent markers (TDH2::GFP, ADK1::mCherry)

- Compete tester strains (L-A-, L-A+, L-A++) against reference under stress conditions

- Monitor population ratios over time using flow cytometry

- Calculate competitive indices based on differential growth rates [28]

Diagram 2: Genome-wide Screening Workflow. This diagram outlines the systematic approach for identifying host factors required for viral maintenance, from initial screening through rigorous validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Virus-Host Interactions

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function/Utility | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast KO Collection | Genomic screening | Identification of non-essential host factors | L-A virus host factor discovery [28] |

| Temperature-sensitive mutants | Essential gene analysis | Assessment of essential host genes under permissive/restrictive conditions | Validation of MAK genes in L-A maintenance [28] |

| TDH2::GFP ADK1::mCherry reference | Competitive fitness assays | Flow cytometry-based quantification of relative fitness | Stress resilience comparison in L-A+ vs L-A- strains [28] |

| Anti-Gag antibodies | Viral protein detection | Western blot confirmation of viral protein expression | Verification of L-A virus presence and load [28] |

| Human dorsal root ganglia | Latency studies | Ex vivo analysis of viral persistence mechanisms | Characterization of VLT transcripts in VZV latency [29] |

| SCID-hu mouse models | In vivo latency studies | Humanized model for viral latency and reactivation | VZV latency and immune infiltration studies [29] |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Future Research