Viral Load Quantification Methods: Correlation, Challenges, and Clinical Applications in Modern Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of viral load quantification methodologies, a cornerstone of clinical virology and therapeutic monitoring.

Viral Load Quantification Methods: Correlation, Challenges, and Clinical Applications in Modern Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of viral load quantification methodologies, a cornerstone of clinical virology and therapeutic monitoring. We explore the foundational principles of molecular-based techniques, including RT-qPCR and ddPCR, and their critical applications in managing infections such as HIV, SARS-CoV-2, and transplant-related viruses. The content delves into persistent standardization challenges, interassay variability, and the impact of different sample matrices on result accuracy. By presenting comparative data and validation strategies, this review serves as a vital resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize viral load quantification for improved diagnostic reliability, treatment efficacy assessment, and public health surveillance.

The Bedrock of Viral Load Quantification: Principles, Significance, and Standardization Hurdles

Viral load (VL) refers to the quantity of a virus in a standardized volume of blood or other bodily fluid [1]. In clinical practice, it is a critical biomarker for monitoring the progression of viral infections and the effectiveness of antiviral therapies. For HIV, viral load "measures the quantity of HIV RNA in the blood," with results expressed as the number of copies per milliliter (copies/mL) of blood plasma [1]. The primary goal of antiretroviral therapy (ART) is suppression of the HIV viral load, making VL monitoring key to assessing treatment success [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has established three key categories for interpreting HIV viral load measurements [2]:

- Unsuppressed: >1000 copies/mL

- Suppressed: Detected but ≤1000 copies/mL

- Undetectable: Viral load not detected by the test used

Achieving an undetectable viral load is a critical public health goal, as people living with HIV who maintain this status have zero risk of transmitting HIV to their sexual partner(s) [2]. Those with a suppressed but detectable viral load have almost zero or negligible risk of transmission [2].

Clinical and Public Health Significance of Viral Load

Prognostic Value and Treatment Monitoring

Viral load serves as a crucial prognostic indicator across viral infections. In HIV management, monitoring a person's viral load is fundamental to assessing the success of ART [1]. Sicker patients generally have more virus than those with less advanced disease, making viral load a key marker of disease progression [1]. The global 95-95-95 targets emphasize achieving viral suppression in 95% of people receiving ART, recognizing its importance for both individual health and epidemic control [3].

Viral Load in Public Health Surveillance

Beyond individual patient care, population-level viral load data provides powerful insights for public health. The distribution of cycle threshold (Ct) values from reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) testing can be used for epidemic nowcasting [4]. Ct values inversely correlate with viral load; lower Ct values indicate higher viral loads and typically suggest recent onset of infection [4]. During an epidemic, a population-level sample with predominantly low Ct values (high viral loads) indicates most sampled infections are recent, corresponding to a growing epidemic. Conversely, predominantly high Ct values (low viral loads) suggest a declining epidemic [4]. This approach complements traditional case count surveillance and has been successfully applied to track SARS-CoV-2 trends [4].

Table 1: Clinical and Public Health Applications of Viral Load Monitoring

| Application Area | Primary Use of Viral Load Data | Key Thresholds/Targets |

|---|---|---|

| HIV Treatment Monitoring | Assess effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (ART) | Undetectable: Target for individual treatmentUnsuppressed (>1000 copies/mL): Indicates need for intervention [2] |

| Prevention of Transmission | Evaluate risk of HIV transmission | Undetectable = Zero sexual transmission risk [2] |

| Epidemic Surveillance | Nowcast epidemic growth rates using population Ct values | Lower average Ct (higher VL) = Growing epidemicHigher average Ct (lower VL) = Declining epidemic [4] |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Monitor response to antiviral treatment (e.g., for HDV) | Precise quantification at low concentrations is critical [5] |

Quantitative Methods for Viral Load Measurement

Established and Emerging Methodologies

Accurate viral load quantification relies on sophisticated molecular techniques. The field is dominated by PCR-based methods, with ongoing innovations enhancing precision and accessibility.

Table 2: Comparison of Viral Load Quantification Technologies

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real-Time RT-PCR | Quantitative PCR using fluorescent probes and standard curves for quantification [6]. | Considered the gold standard; widely automated and established [6]. | Quantification depends on standard curves, introducing variability; susceptible to PCR inhibitors [6]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Partitions sample into thousands of nanoreactions for absolute target counting without standard curves [6]. | Superior accuracy and precision, especially for medium/high viral loads; less susceptible to inhibitors [6]. | Higher costs; reduced automation compared to Real-Time RT-PCR [6]. |

| Point-of-Care (POC) Tests | Simplified, rapid tests for use in decentralized settings [7]. | Increases monitoring coverage in resource-limited settings; uses alternative samples (e.g., dried blood spots) [7] [2]. | May have different performance characteristics compared to laboratory-based tests [2]. |

Performance Comparison: dPCR vs. Real-Time RT-PCR

A 2025 comparative study of respiratory virus diagnostics during the 2023-2024 "tripledemic" provided robust experimental data on the performance of dPCR versus Real-Time RT-PCR [6]. The study analyzed 123 respiratory samples positive for influenza A, influenza B, RSV, or SARS-CoV-2, stratified by Ct values into high (Ct ≤25), medium (Ct 25.1–30), and low (Ct >30) viral load categories [6].

Table 3: Experimental Performance Data: dPCR vs. Real-Time RT-PCR [6]

| Virus | Viral Load Category | Method with Superior Accuracy | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | High | dPCR | dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy for high viral loads. |

| Influenza B | High | dPCR | dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy for high viral loads. |

| SARS-CoV-2 | High | dPCR | dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy for high viral loads. |

| RSV | Medium | dPCR | dPCR showed greater consistency and precision for quantifying intermediate viral levels. |

| All Viruses | - | dPCR | dPCR showed greater overall consistency and precision than Real-Time RT-PCR. |

The study concluded that dPCR offers absolute quantification without standard curves and demonstrates superior accuracy, particularly for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads of RSV [6]. However, the authors noted that the routine implementation of dPCR is currently limited by higher costs and reduced automation compared to Real-Time RT-PCR [6].

Experimental Protocols for Viral Load Quantification

Detailed dPCR Workflow for Respiratory Viruses

The following protocol is adapted from a 2025 study comparing dPCR and Real-Time RT-PCR for respiratory virus quantification [6].

1. Sample Collection and Storage

- Collect nasopharyngeal swabs or other respiratory samples (e.g., bronchoalveolar lavage) in appropriate viral transport media.

- Store samples at 4°C for processing within 72 hours or at -80°C for long-term storage.

2. Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Use an automated extraction system, such as the KingFisher Flex system.

- Employ a viral RNA/DNA extraction kit, such as the MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit.

- Elute nucleic acids in nuclease-free water or the elution buffer provided by the kit.

3. Digital PCR Assay Setup

- Platform: Use a nanowell-based dPCR system (e.g., QIAcuity from QIAGEN).

- Reaction Mix: Prepare a multiplex dPCR reaction containing:

- dPCR supermix

- Optimized primer-probe sets specific for each target (e.g., influenza A, influenza B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2)

- An internal control to monitor extraction and amplification efficiency

- The extracted nucleic acid template

- Partitioning: Load the reaction mix into a nanowell plate, which partitions the sample into approximately 26,000 individual reactions.

4. Endpoint PCR Amplification

- Run the partitioned plate on a thermal cycler using cycling conditions optimized for the primer-probe sets and dPCR instrument.

- Standard cycling conditions include: reverse transcription, polymerase activation, and 40-45 cycles of denaturation/annealing-extension.

5. Fluorescence Reading and Data Analysis

- After amplification, the dPCR instrument reads the fluorescence in each nanowell.

- Use instrument software (e.g., QIAcuity Suite Software) to analyze the fluorescence data and determine the absolute copy number (copies/μL) of each target in the original sample based on the ratio of positive to negative wells (Poisson statistics).

HDV RNA Quantification Assay Comparison Protocol

A 2025 quality control study highlights the critical protocol elements for reliable HDV RNA monitoring, which is paramount for assessing response to anti-HDV therapy [5].

Objective: To compare the diagnostic performance of different quantitative HDV-RNA assays used in clinical practice.

Methodology:

- Sample Panels: Two panels were distributed to 30 testing centers.

- Panel A: 8 serial dilutions of a WHO/HDV standard (range: 0.5–5.0 log10 IU/mL).

- Panel B: 20 clinical samples (range: 0.5–6.0 log10 IU/mL).

- Participating Assays: Multiple commercial assays (e.g., RoboGene, EurobioPlex, RealStar, AltoStar, Bosphore) and in-house assays.

- Performance Metrics:

- Sensitivity: Determined by the 95% Limit of Detection (LOD).

- Precision: Calculated as intra- and inter-run Coefficient of Variation (CV).

- Accuracy: Assessed by the difference between expected and observed HDV-RNA levels.

- Linearity: Evaluated by linear regression analysis (R²).

Key Findings:

- Sensitivity: The 95% LOD varied significantly across assays, from 3 IU/mL (AltoStar) to 100-316 IU/mL (EuroBioplex).

- Accuracy: Six assays showed minimal bias (<0.5 log10 IU/mL), while others had >1 log10 underestimations.

- Precision: RealStar, Bosphore-on-InGenius, and EurobioPlex showed the highest precision (mean intra-run CV <20%).

- Linearity: Most assays showed good linearity (R² >0.90) overall, but performance at low viral loads (<1000 IU/mL) varied.

This study underscores the heterogeneous sensitivities of different HDV-RNA assays, which can hamper proper quantification, particularly at low viral loads, and raises the need for improved assay performance [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Viral Load Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Viral Load Assays | Exemplars / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction Systems | Isolate viral RNA/DNA from clinical samples with high purity and consistency, minimizing cross-contamination. | STARlet Seegene platform [6], KingFisher Flex system [6]. |

| Extraction Kits | Contain optimized buffers and magnetic beads for specific binding and elution of nucleic acids. | MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit [6], STARMag Universal Cartridge Kit [6]. |

| dPCR Supermix | A ready-to-use master mix containing polymerase, dNTPs, and stabilizers optimized for partitioning and endpoint amplification. | QIAcuity PCR Master Mix [6]. |

| Primer-Probe Sets | Target-specific oligonucleotides for amplification and fluorescent detection of the viral genome. | Commercially validated, multiplexable sets for viruses (e.g., Influenza A/B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) [6]. |

| dPCR Partitioning Plates/Cartridges | Microfluidic chips or plates that physically partition the PCR reaction into thousands of individual reactions. | QIAcuity nanoplates [6]. |

| WHO International Standards | Provide a universal reference for calibrating assays, enabling comparability of results across labs and methods. | WHO/HDV standard [5]. |

| Internal Controls | Non-target nucleic sequences added to the sample to monitor the efficiency of nucleic acid extraction and amplification. | Critical for identifying PCR inhibition and validating negative results [6]. |

Viral load quantification remains a cornerstone of modern virology, with critical applications spanning individual patient prognosis, therapeutic monitoring, and public health surveillance. While Real-Time RT-PCR continues to be the workhorse technology in clinical laboratories, Digital PCR is emerging as a more precise alternative for absolute quantification, particularly beneficial for research and resolving equivocal results [6]. The choice of methodology must balance accuracy, cost, and throughput requirements.

Future progress hinges on standardizing assays across platforms, as evidenced by the variability in HDV RNA testing [5], and on improving access to reliable viral load monitoring in decentralized settings through point-of-care technologies and alternative sample types [7] [2]. As viral load research continues to evolve, its integration into clinical and public health practice will be fundamental to managing existing epidemics and preparing for future viral threats.

The accurate quantification of viral load is a cornerstone of modern molecular diagnostics, profoundly impacting patient management, therapeutic monitoring, and public health surveillance [8]. For years, Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) has served as the gold standard for detecting RNA viruses. However, the evolving demands of clinical research, particularly the need for absolute quantification and enhanced sensitivity for low viral loads, have highlighted certain limitations of this technique [9]. Digital PCR (dPCR), and its droplet-based counterpart ddPCR, represent a paradigm shift in nucleic acid quantification, offering a fundamentally different approach that does not rely on external calibration curves [10]. This guide objectively compares the performance of RT-qPCR and ddPCR platforms, framing the analysis within the critical context of viral load quantification method correlation research for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

RT-qPCR is a relative quantification method. It works by reverse transcribing RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), which is then amplified in a real-time thermal cycler. The instrument monitors fluorescence during each PCR cycle, and the cycle threshold (Ct) at which the fluorescence crosses a predefined level is used to estimate the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid. This estimation requires a standard curve constructed from samples of known concentration [10] [9]. The entire process occurs in a single, bulk reaction, making its efficiency susceptible to inhibitors present in the sample and sequence variations affecting primer binding [8].

ddPCR, a variant of dPCR, achieves absolute quantification through sample partitioning. The reaction mixture is divided into thousands to millions of nanoliter-sized droplets, with each droplet functioning as an individual PCR reactor [11]. After end-point PCR amplification, the droplets are analyzed to count the number that contains the target sequence (positive) versus those that do not (negative). The absolute concentration of the target nucleic acid, in copies per microliter of input, is then calculated directly using Poisson statistics, eliminating the need for a standard curve [10] [12].

The workflow for nanoplate-based dPCR systems, such as the QIAcuity, integrates partitioning, thermocycling, and imaging into a single, fully automated instrument, enabling a streamlined process from sample to result in under two hours [12].

Side-by-Side Technical Comparison

Table 1: Core Technical Characteristics of RT-qPCR and ddPCR.

| Feature | RT-qPCR | ddPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Type | Relative (requires standard curve) [10] [9] | Absolute (no standard curve) [10] [12] |

| Measurement Basis | Cycle threshold (Ct) during exponential phase [12] | End-point counting of positive partitions [11] [12] |

| Dynamic Range | Broad [10] | Limited by number of partitions [8] |

| Sensitivity & Precision | High for most routine applications | Superior for rare targets and low-abundance sequences [10] [12] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Susceptible to PCR inhibitors [10] | High tolerance due to sample partitioning [10] [8] |

| Tolerance to Amplification Efficiency Variations | Highly affected [12] | Largely unaffected [12] |

| Detection of Rare Mutations | Mutation rate >1% [12] | Mutation rate ≥0.1% [12] |

| Throughput & Speed | High throughput, established fast protocols [10] | Traditionally lower throughput; newer nanoplate systems offer higher speed and automation [6] [12] |

| Cost Considerations | Lower per-sample cost, well-established [10] | Higher cost per sample, though becoming more competitive [6] |

Experimental Data in Viral Load Quantification

Performance in Clinical and Environmental Surveillance

Recent studies directly comparing these platforms provide compelling evidence of their respective performances. A 2025 study on respiratory viruses (Influenza A/B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) found that dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy and precision, particularly for samples with high viral loads and medium loads of RSV [6]. The technology showed greater consistency than RT-qPCR in quantifying intermediate viral levels, which is crucial for accurate disease progression monitoring [6].

In environmental applications, such as wastewater surveillance, ddPCR's superior sensitivity is vital for early outbreak detection. One study reported that for the trace detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater, the assay limit of detection (ALOD) for ddPCR was approximately 2–5 times lower than that for RT-qPCR [13]. In another study analyzing 50 wastewater samples with low viral load, an RT-ddPCR assay detected SARS-CoV-2 in all 50 samples, whereas RT-qPCR only concurrently detected the virus in 21 samples, with 4 samples testing negative [11]. This demonstrates ddPCR's power in low-prevalence and trace-level monitoring scenarios.

Impact on Clinical Trial Assessment

A pivotal 2025 study underscored how the choice of molecular platform can directly influence the assessment of antiviral drug efficacy [9]. In clinical trials for the drug Azvudine, the viral load quantified by RT-qPCR showed no significant difference between the antiviral-treated and placebo groups. However, when the same samples were analyzed using ddPCR, a significant reduction in viral load was observed in the treated group on days 3, 5, 7, and 9 post-treatment [9]. This critical finding indicates that ddPCR's enhanced sensitivity and absolute quantification can uncover treatment effects that may be obscured by the variability and logarithmic approximations inherent in RT-qPCR standard curve-based quantification.

Table 2: Summary of Key Comparative Study Findings.

| Study Context | Key Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Virus Detection (2025) [6] | dPCR showed superior accuracy for high viral loads (Influenza A/B, SARS-CoV-2) and medium loads (RSV). | Enhanced diagnostic accuracy and better understanding of co-infection dynamics. |

| Wastewater Surveillance [11] [13] | RT-ddPCR ALOD 2-5x lower than RT-qPCR; higher detection rates in low-prevalence samples. | More effective early warning system for community-level outbreaks. |

| Antiviral Clinical Trial (2025) [9] | ddPCR revealed significant viral load reduction post-treatment; RT-qPCR showed no significant difference. | More sensitive and reliable measurement of therapeutic efficacy in drug development. |

| SARS-CoV-2 Variant Detection [11] | RT-ddPCR assay showed high repeatability (CV <10%) and low limits of detection (e.g., ~4 copies/reaction for N gene). | Robust tool for precise quantification and tracking of emerging variants. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

For researchers seeking to validate or compare these technologies, the following outlines a generalized experimental protocol based on cited studies.

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Sample Type: The choice of sample matrix (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage, wastewater) should reflect the research question [6] [11]. For wastewater, a concentration step (e.g., ultrafiltration) is often required prior to extraction [11].

- RNA Extraction: Use commercial kits designed for viral RNA purification (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit, QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit) from automated or manual platforms [6] [11] [13]. It is critical to include an internal control during extraction to monitor efficiency and potential inhibition [13].

- Sample Stratification: To ensure a comprehensive comparison, stratify samples based on RT-qPCR Ct values into categories such as high (Ct ≤ 25), medium (Ct 25.1–30), and low (Ct > 30) viral load [6].

Assay Design and Platform-Specific Workflows

- Primer/Probe Design: Design or select primer-probe sets targeting conserved viral genes (e.g., N and S genes for SARS-CoV-2) [11]. For multiplexing, use fluorophores with non-overlapping emission spectra.

- RT-qPCR Workflow:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing reverse transcriptase, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, primers, probes, and buffer. Aliquot into reaction wells and add template RNA.

- Thermocycling: Run on a real-time cycler with a program typically including reverse transcription, polymerase activation, and 40-45 cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension.

- Data Analysis: Generate a standard curve from serial dilutions of a known standard. Determine the quantity of unknown samples by interpolation from the standard curve based on their Ct values [11] [9].

- ddPCR Workflow:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a similar master mix, often optimized for the specific digital platform.

- Partitioning: On a droplet generator or nanoplate system, partition each sample reaction mixture into thousands of individual droplets or nanowells [6] [11].

- PCR Amplification: Perform end-point PCR on the partitioned sample.

- Droplet Reading and Analysis: Run the plate on a droplet reader that counts the positive and negative partitions for each sample. The software then applies Poisson statistics to calculate the absolute concentration of the target (copies/μL) [11] [12].

Data Analysis and Correlation

- Statistical Comparison: Use correlation analyses (e.g., Spearman's rank correlation) and measures of agreement (e.g., Cohen's kappa) to compare the quantitative results and detection rates between the two platforms [6] [11].

- Sensitivity and LOD Calculation: Determine the absolute limit of detection (LOD) for each platform by testing serial dilutions of the target nucleic acid. The LOD is typically defined as the lowest concentration at which ≥95% of replicates are positive [11].

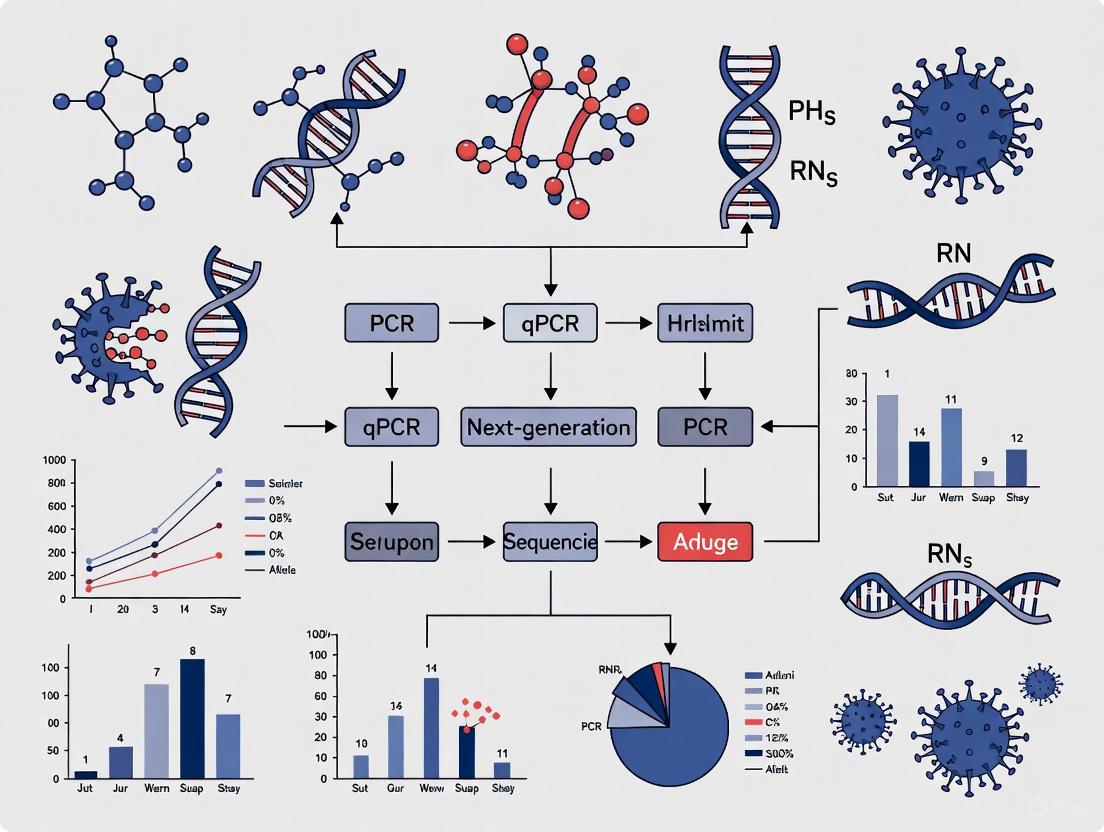

Diagram Title: Comparative Workflow of RT-qPCR and ddPCR for Viral Load Quantification

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation and comparison of these platforms depend on a suite of critical reagents and kits.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Viral Load Quantification Studies.

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Viral RNA Extraction Kits (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini, RNeasy Mini, MagMax Viral/Pathogen) | Purification and isolation of viral RNA from complex sample matrices like swabs or wastewater. | Essential first step for all downstream molecular analysis; ensures high-quality, inhibitor-free RNA [11] [13]. |

| One-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix | Contains reverse transcriptase and hot-start DNA polymerase in an optimized buffer for direct amplification of RNA targets. | Streamlines the RT-qPCR workflow, reducing pipetting steps and potential contamination [13]. |

| ddPCR Supermix (for Probes) | Optimized reaction mix for digital PCR applications, ensuring stable droplet formation and efficient amplification. | Critical for generating robust and reproducible data on droplet-based systems [11]. |

| Primer/Probe Sets | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target detection. Probes are typically labeled with fluorophores (FAM, VIC/HEX). | Fundamental for assay specificity; dual-labeled probe sets allow for multiplex detection of different viral targets [11]. |

| Quantified RNA Standards | Synthetic or biologically derived RNA of known concentration for generating standard curves. | Required for absolute quantification and determining the assay's limit of detection (LOD) in RT-qPCR [9]. |

| Inhibition Control (e.g., Murine Hepatitis Virus - MHV) | Exogenous control added to the sample to monitor for the presence of PCR inhibitors. | Added to samples prior to extraction to assess RNA extraction efficiency and identify inhibition in downstream assays [13]. |

Both RT-qPCR and ddPCR are powerful molecular techniques with distinct strengths that recommend them for different applications within viral load quantification research. RT-qPCR remains the workhorse for high-throughput, routine diagnostics due to its broad dynamic range, established protocols, and lower cost [10]. In contrast, ddPCR excels in scenarios demanding high precision, absolute quantification without standards, superior sensitivity for low viral loads, and resilience to inhibitors or sequence variations [6] [11] [9].

The choice between platforms should be guided by the specific research objectives. For drug development professionals, the ability of ddPCR to reveal subtle changes in viral load during antiviral therapy trials makes it an invaluable tool for assessing treatment efficacy [9]. For public health researchers, its enhanced sensitivity is crucial for wastewater-based epidemiology and early outbreak detection [11] [13]. As the field advances, the trend is not necessarily toward replacement but toward the complementary use of both technologies, leveraging their respective advantages to paint a more complete and accurate picture of viral dynamics.

Viral load quantification represents a critical pillar in the management and treatment of viral infections, serving as a cornerstone for clinical decision-making, treatment efficacy monitoring, and drug development. For both Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), precise viral load measurement is indispensable for guiding treatment initiation, assessing therapeutic success, and preventing drug resistance [14]. Despite technological advancements, the diagnostic landscape remains fragmented with multiple platforms, reagents, and methodologies, creating substantial challenges in result interpretation, clinical trial data comparison, and patient management across different sites and studies.

This variability is particularly problematic for global health initiatives and multi-center clinical trials, where standardized outcomes are essential for valid data comparison. The World Health Organization's 2030 goals of reaching 95% HIV diagnosis/treatment coverage and reducing HCV incidence by 90% face significant obstacles due to insufficient diagnostic tools and lack of harmonization across testing platforms [14]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of current viral load quantification technologies for HIV and HCV, analyzes their performance characteristics, and underscores the imperative for standardized approaches in viral load monitoring to advance both clinical management and drug development pipelines.

Performance Comparison of Viral Load Assays

HCV RNA Quantification Assays

The performance characteristics of four commercially available HCV RNA quantification reagents were evaluated using multiple serum panels to assess analytical sensitivity, specificity, precision, and genotype inclusivity. These reagents employed real-time PCR technology with the PCR-fluorescence probing method commonly used in diagnostic laboratories [15].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of HCV RNA Quantification Assays

| Reagent | Analytical Sensitivity | Analytical Specificity | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Intra-assay CV | Inter-assay CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 100% | 100% | 25 IU/mL | 1.48-4.37% | 1.74-4.84% |

| B | 100% | 100% | 50 IU/mL | 1.48-4.37% | 1.74-4.84% |

| C | 100% | 100% | 50 IU/mL | 1.48-4.37% | 1.74-4.84% |

| D | 100% | 100% | 50 IU/mL | 1.48-4.37% | 1.74-4.84% |

All four reagents demonstrated 100% analytical sensitivity and specificity (95% CI: 79.95-100), with no cross-reactivity to common interfering substances or viruses such as HBV and HIV. The reagents showed strong linear correlations (R² > 0.95) between measured and expected HCV RNA levels across their respective quantitative ranges [15]. The evaluation utilized seven distinct serum panels: basic, analytical specificity, seroconversion, analytical sensitivity, precision, genotype qualification, and linearity panels to ensure comprehensive assessment.

For genotype detection, all assays successfully detected and quantified HCV genotypes 1-6, which is crucial given the geographical distribution of HCV genotypes. In China, for instance, GT1b and GT2a are the most common subtypes, though emerging subtypes (GT3 and GT6) in southern regions necessitate genotype-inclusive diagnostic assays to prevent detection failures [15]. The robust performance across diverse genotypes ensures utility in global contexts and multi-center trials.

HIV-1 Viral Load Assays

HIV-1 viral load monitoring has evolved significantly, with current research focusing on both improved laboratory methods and alternative sampling approaches to increase testing accessibility.

Table 2: HIV-1 Viral Load Assay Performance and Method Comparisons

| Method/Assay | Sample Type | Correlation with Reference | Mean Difference | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dried Blood Spot (DBS) | Whole blood on filter paper | r = 0.796 (p < 0.001) | 0.66 ± 0.70 log copies/mL | Resource-limited settings |

| Plasma vs Serum | Plasma/Serum pairs | Strong correlation | Minimal bias | Serum alternative for specific settings |

| Novel Rapid Test | Finger-prick blood | R² = 0.97-0.99 with reference | Not specified | Point-of-care settings |

A study comparing dried blood spot (DBS) and plasma HIV-1 viral load measurements using the Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan assay demonstrated a strong correlation (r = 0.796, p < 0.001) between these methods [16]. The mean difference between DBS and plasma measurements was 0.66 ± 0.70 log copies/mL, suggesting that DBS samples could be a suitable alternative for periodic monitoring of HIV-1 viral loads, particularly in resource-limited settings due to minimal invasive blood collection, higher stability at room temperature, and ease of transportation [16].

Similarly, a comparative evaluation of plasma and serum HIV-1 viral load measurements found strong correlation between these sample types, indicating that serum might be a suitable alternative sample for periodic monitoring of HIV viral load, especially in specific clinical circumstances such as when patients are undergoing antenatal care services where serum is the most commonly available test sample [17].

Emerging technologies are further revolutionizing viral load monitoring. A recent development in rapid simultaneous self-testing for HIV and HCV viral loads integrates RNA extraction and multiplex RT-PCR in a single portable device [14]. This system uses only 100 μL of finger-prick blood and provides results in under one hour, achieving a limit of detection (LOD) of 5 copies/reaction and demonstrating strong correlation (R² = 0.97-0.99) with standard Bio-Rad benchtop systems [14].

Impact of Viral Load Thresholds on Clinical Outcomes

HIV Viral Load Thresholds and Diagnostic Challenges

The establishment of appropriate viral load thresholds has significant implications for diagnosis and monitoring. China's diagnostic guidelines recently lowered the viral load threshold from 5,000 to 1,000 copies/mL for HIV diagnosis [18]. This change demonstrated a significant improvement in detection rates - when using 5,000 copies/mL as the threshold, the HIV positivity rate was 89.87%, which increased to 97.46% when the threshold was lowered to 1,000 copies/mL (P = 0.009) [18].

Despite this improvement, challenges remain in acute HIV infection (AHI) diagnosis. A study analyzing the Beijing PRIMO cohort found that 4 cases (1.15%) had viral loads < 1,000 copies/mL prior to confirmed positive antibody results, with the longest interval between a viral load < 1,000 copies/mL and a subsequent positive Western blot result being 42 days [18]. This highlights the diagnostic significance of low-level viremia during the serological window period and supports the prioritization of nucleic acid testing (NAT) for individuals with high-risk profiles and negative or indeterminate antibodies to shorten the diagnostic window.

Viral Suppression Metrics in HIV Care

The definition of viral suppression also varies across guidelines and programs, impacting reported outcomes. A study examining differences between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition of viral suppression used by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) - last viral load measurement <200 copies/mL - and more robust definitions of durable viral suppression found significant variations [3].

While 94-95% of individuals met the CDC definition of viral suppression, when alternative metrics requiring all viral loads under 200 copies/mL with either (1) one viral load required; (2) two viral loads required; or (3) two viral loads more than 90 days apart required, annual rates of viral suppression dropped to 87-92% [3]. These findings demonstrate that current metrics may overestimate sustained viral suppression, with implications for both clinical management and public health reporting.

Experimental Protocols for Viral Load Assay Evaluation

Standardized Evaluation Framework for HCV Assays

The performance evaluation of HCV RNA quantification reagents followed a rigorous protocol based on the "Protocol for the laboratory evaluation of HCV molecular assays" and "Guidance on test method validation for in vitro diagnostic medical devices" issued by WHO [15]. The evaluation incorporated multiple serum panels:

- HCV RNA Basic Serum Panel: Comprised 40 serum samples (20 HCV RNA-positive and 20 HCV RNA-negative) to evaluate initial analytical sensitivity and specificity.

- Analytical Specificity Panel: Contained 40 serum samples negative for HCV antibodies and HCV RNA but positive for HBV or HIV, plus samples exhibiting hemolysis, lipemia, or other interference factors.

- Seroconversion Panel: Utilized the PHV928 panel (SeraCare Life Sciences) consisting of 9 vials of serum samples to evaluate early detection sensitivity.

- Analytical Sensitivity Panel: Employed samples prepared by diluting the WHO International Standard for HCV RNA to determine the limit of detection.

- Precision Panel: Assessed both intra-assay and inter-assay variability across multiple runs.

- Genotype Qualification Panel: Evaluated detection capability across HCV genotypes 1-6.

- Linearity Panel: Assessed the quantitative linear range of each assay.

All stock specimens from HCV RNA serum panels were tested in parallel with the four reagents following manufacturers' instructions, with operations and data analysis conducted under blinded or double-blinded conditions to minimize bias [15].

HIV Viral Load Comparison Methodology

The comparative evaluation of DBS versus plasma HIV-1 viral load measurements followed a standardized protocol [16]. Participants provided 4 mL of venous blood collected in EDTA anticoagulant tubes. For DBS preparation, approximately 50 μL of blood was dispensed onto Whatman 903 filter paper cards with five spots per card. The blood spots were air-dried at room temperature for 4-6 hours and stored in zip-lock plastic bags with silica gel desiccant pouches. Plasma was harvested from whole blood samples via centrifugation at 2500 RPM for 10 minutes.

HIV-1 RNA extraction from DBS samples utilized two half-spots (6mm in diameter) trimmed from each filter paper card, while plasma samples used 1100 μL aliquots. The COBAS AmpliPrep instrument performed automated specimen processing based on silica-based capture principles. The quantification was performed using the COBAS TaqMan version 2.0 Analyzer, with detection utilizing HIV-1-specific oligonucleotide probes labeled with fluorescent dye [16].

Statistical analysis included Pearson's correlation to assess the relationship between plasma and DBS measurements and Bland-Altman plots to evaluate the level of agreement and identify potential proportional bias between the two methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Load Quantification Studies

| Reagent/Material | Manufacturer/Example | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV RNA Quantification Reagents | Wantai BioPharm, Daan Gene, Beijing NaGene, Kehua Bio-Engineering | HCV RNA detection and quantification | Real-time PCR with fluorescence probing, LOD: 25-50 IU/mL |

| HIV-1 Viral Load Assay | Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan v2.0 | HIV-1 RNA extraction and quantification | Automated system, LOD: <20 copies/mL |

| DBS Filter Paper | Whatman 903 | Sample collection and storage | Standardized cellulose matrix for blood collection |

| RNA Extraction Kit | QIAGEN QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit | Nucleic acid purification | Silica-based membrane technology |

| International Standards | WHO International Standard for HCV RNA | Assay calibration and standardization | Traceable reference materials |

| Multiplex RT-PCR Reagents | Custom formulations | Simultaneous detection of multiple targets | Enables HIV/HCV co-testing |

| Quality Control Panels | SeraCare Life Sciences | Assay validation and QC | Characterized performance panels |

The selection of appropriate reagents and materials is critical for robust viral load quantification. International standards, such as the WHO International Standard for HCV RNA, play a vital role in assay calibration and harmonization across different platforms and laboratories [15]. Quality control panels with characterized performance metrics are essential for both initial validation and ongoing quality assurance.

For emerging technologies, such as the rapid multiplex HIV/HCV testing platform, specialized reagents enabling rapid RNA extraction and accelerated thermal cycling are necessary. The system developed by Liu and colleagues achieves complete RNA extraction and multiplex RT-PCR in under 60 minutes through optimized reagent formulations and accelerated thermal cycling protocols with 1-second denaturation and extension steps [14].

The comparative analysis of viral load quantification technologies for HIV and HCV reveals both significant advancements and critical challenges in standardization. While current assays demonstrate excellent performance characteristics - with high sensitivity, specificity, and precision - variability in platforms, methodologies, and definitions of key thresholds creates substantial obstacles for both clinical management and drug development.

The emergence of novel technologies, such as rapid multiplex testing platforms and alternative sampling methods like DBS, offers promising opportunities to expand testing accessibility and efficiency. However, these innovations must be accompanied by robust standardization efforts to ensure result comparability across different settings and platforms.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the imperative for standardization extends beyond technical performance to encompass clinical endpoints and reporting metrics. Harmonized definitions of virologic suppression, standardized evaluation protocols, and traceable reference materials are essential components of a cohesive viral load quantification ecosystem. As we strive toward global elimination targets for both HIV and HCV, a renewed focus on standardization will be crucial for accurate disease monitoring, effective treatment evaluation, and successful drug development.

Interassay variability represents a fundamental challenge in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, particularly in the field of viral load quantification. This variability refers to the differences in measurement results that occur when the same sample is tested using different assays, instruments, or reagent systems. The lack of universal standards across testing platforms creates significant obstacles for comparing data across studies, establishing consistent clinical thresholds, and ensuring reproducible research outcomes. In viral load quantification, where precise measurements directly influence clinical decisions and research conclusions, this variability can undermine the validity and translational potential of scientific findings.

The core of this challenge lies in the absence of standardized reference materials and harmonized protocols. Different manufacturers utilize unique calibration standards, reagent formulations, and measurement technologies, leading to systematic differences in reported values. Even when assays target the same analyte, these methodological differences can produce substantially divergent results. The establishment of universal standards is therefore critical not only for improving the reliability of individual assays but also for enabling meaningful correlations across different viral load quantification methods.

Experimental Evidence of Interassay Variability

Variability in TROP2 Immunohistochemistry Assays

A 2025 study investigating TROP2 expression in triple-negative breast cancer provides compelling evidence of significant interassay variability. Researchers analyzed 26 tumor samples using three different immunohistochemistry assays on a Dako Omnis platform according to manufacturer protocols [19].

The experimental protocol involved:

- Sample Preparation: Twenty-six triple-negative breast cancer samples were processed for analysis.

- Assay Systems: Three different immunohistochemistry assays were employed: ENZO-ABS380-0100 (Assay A, used in ASCENT trial), Abcam SP295 (Assay B, used in TROPiCS-02 trial), and Santa Cruz B9-sc-376746 (Assay C, used in cross-sectional studies).

- Quantification Method: TROP2 expression on tumor cell membranes was quantified using the H-score system, with categories defined as low (H-score ≤ 100), intermediate (> 101 to ≤ 200), and high (> 200).

- Statistical Analysis: Assay agreement was evaluated using Cohen's κ and Gwet's AC2 statistics.

The results demonstrated striking disparities in TROP2 expression classification across the three assays [19]:

Table 1: TROP2 Expression Classification Across Different Assays

| Assay | Low Expressors | Intermediate Expressors | High Expressors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assay A | 57.7% (n=15) | 34.6% (n=9) | 7.7% (n=2) |

| Assay B | 19.2% (n=5) | 42.3% (n=11) | 38.4% (n=10) |

| Assay C | 15.4% (n=4) | 46.2% (n=12) | 38.4% (n=10) |

The overall concordance between all three assays was only fair to moderate (AC2 = 0.35, p = 0.0067), while assays B and C showed substantial agreement (80.8% concordance, κ = 0.81; p < 0.0001). These findings highlight how assay selection can dramatically influence biomarker classification, potentially affecting patient stratification for targeted therapies like sacituzumab govitecan [19].

Variability in Direct Oral Anticoagulant (DOAC) Monitoring

A study investigating interassay variability between direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) calibrated anti-factor Xa assays further demonstrates this challenge in clinical measurement [20]. The experimental protocol included:

- Sample Collection: 70 apixaban and 59 rivaroxaban samples from participants in the Perioperative Anticoagulation Use for Surgery Evaluation trial.

- Testing Platforms: Simultaneous testing using Biophen reagents on BCS XP analyzer (Siemens), HemosIL reagents on ACL TOP analyzer (Werfen), and Stago reagents on STA CompactMAX analyzer (Diagnostica Stago).

- Analysis Method: Interassay correlations were analyzed at the predetermined clinical cutoff of 30 ng/mL and compared with median anti-FXa levels.

The results showed moderate-to-very strong correlations for both apixaban (r = 0.7271-0.9467) and rivaroxaban (r = 0.6531-0.9702). Despite these correlations, anti-FXa levels were significantly different between all instrument-reagent combinations in samples below 30 ng/mL. Importantly, 7.8% (10/129) of samples were discrepantly classified across the 30 ng/mL clinical threshold, potentially affecting clinical decision-making regarding urgent procedures [20].

Establishing Universal Standards for Viral Detection

Development of a Universal SARS-CoV-2 Standard

To address the critical need for standardization in viral detection, researchers have developed a universal national standard for both SARS-CoV-2 antigen and nucleic acid detection [21] [22]. The experimental methodology for this development included:

- Viral Preparation: A SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 strain (hCoV-19/Hong Kong/HKU-691/2021) was cultured with Vero cells and inactivated using β-propiolactone (BPL).

- Inactivation Comparison: The impact of heat inactivation and BPL inactivation on detection was compared using digital PCR (dPCR), qPCR, and sequencing.

- Value Assignment: The concentration was assigned via multi-laboratory digital PCR involving three different dPCR systems.

- Standard Preparation: Bulk preparations were lyophilized into 3 mL vials with 0.5 mL per vial and stored at -20°C.

- Validation Testing: The standard was used to evaluate the limits of detection (LoDs) of commercial antigen rapid detection tests (Ag-RDTs) and nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) using a common unitage.

The research demonstrated that BPL inactivation maintained comparable nucleic acid titers to heat inactivation while preserving better antigen activity. The national standard concentration was assigned as 1.04 × 10^8 Unit/mL (standard uncertainty: 3.48 × 10^6 Unit/mL) [21]. Utilizing this universal standard enabled direct comparison of LoDs between Ag-RDTs and NAATs, revealing that while NAATs generally exhibited lower LoDs, some Ag-RDT sensitivity approached NAAT levels [22].

This universal standard represents a significant advancement as it overcomes the historical challenge of quantifying viral antigens without a standardized unit of measurement, which previously hindered precise analytical evaluation of Ag-RDTs and comparison with NAATs [21].

Regulatory Frameworks for Standardization

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) plays a critical role in establishing public quality standards that support the design, manufacture, testing, and regulation of drug substances and products [23]. Regulatory agencies recognize that USP standards strengthen quality, streamline development, support regulatory compliance, and increase regulatory predictability for drugs. The development of these standards involves a collaborative process with industry stakeholders, regulatory decision-makers, and scientific experts [23].

The establishment of universal standards for prescription container labeling demonstrates the importance of standardization in improving patient outcomes. Wide variability in prescription labels across individual prescriptions, pharmacies, and states can contribute to medication errors. The USP standards address this by providing specific direction on organizing labels in a patient-centered manner that improves readability and gives explicit instructions [24].

Methodological Approaches to Mitigate Variability

Matched Pairs Analysis

Research published in the Journal of Cheminformatics demonstrates that analyzing potency differences between matched compound pairs can reduce the impact of interassay variability [25] [26]. The methodology for this approach involves:

- Data Curation: Implementing minimal and maximal curation procedures for Ki and IC50 data from the ChEMBL32 database.

- Pair Identification: Using the rdRascalMCES algorithm to identify structural analogs between compatible assays based on Maximum Common Edge Subgraphs (MCES).

- Analysis Method: Calculating the difference in pChEMBL values for matched pairs within the same assay, then comparing these differences across assays (ΔΔpChEMBL).

- Statistical Evaluation: Assessing data quality using Median Absolute Error (MAE) and fractions of values exceeding 0.3 (F > 0.3) and 1.0 (F > 1.0) pChEMBL units.

This study revealed that potency differences between matched pairs exhibit less variability than individual compound measurements, suggesting that systematic assay differences may partially cancel out in paired data. The data showed that with minimal curation, agreement within 0.3 pChEMBL units was 44-46% for Ki and IC50 values, improving to 66-79% with extensive curation. Similarly, the percentage of pairs with differences exceeding 1 pChEMBL unit dropped from 12-15% to 6-8% with maximal curation [25].

Statistical Quantification of Variability

Proper quantification of interassay variability is essential for assessing methodological reliability. The coefficient of variability (CV) provides a standardized approach for this quantification [27]:

- Inter-Assay CV: Measures plate-to-plate consistency, calculated from the mean values for high and low controls on each plate. Acceptable inter-assay CVs are generally less than 15%.

- Intra-Assay CV: Measures the variability between duplicate measurements within the same assay plate. Acceptable intra-assay CVs should be less than 10%.

The calculation involves determining the standard deviation of measurements divided by the mean of the measurements, expressed as a percentage. Poor intra-assay CVs (>10%) often reflect technical issues such as pipetting errors, sample handling problems, or equipment calibration issues [27].

Visualization of Experimental Approaches

The following workflow diagrams illustrate key experimental methodologies discussed in this review for assessing and mitigating interassay variability.

Diagram 1: TROP2 IHC variability assessment. This workflow illustrates the experimental approach used to evaluate interassay variability in TROP2 immunohistochemistry staining, from sample processing through statistical analysis of concordance [19].

Diagram 2: Universal standard development process. This workflow outlines the key steps in establishing a universal standard for SARS-CoV-2 detection, enabling direct comparison between antigen and nucleic acid tests [21] [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for Standardization

The following table details essential research reagents and materials critical for conducting standardized viral load quantification and addressing interassay variability.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Standardization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| β-Propiolactone (BPL) | Virus inactivation while preserving antigen integrity | Universal standard preparation for SARS-CoV-2 [21] |

| Digital PCR Systems | Absolute nucleic acid quantification without calibration curves | Value assignment for universal standards [21] |

| Reference Standards | Calibrator materials with assigned unitage | Harmonizing measurements across different platforms [21] |

| Matched Molecular Pairs | Structural analogs for comparing potency differences | Assessing interassay variability in chemical datasets [25] |

| Quality Controls | High and low concentration controls for precision monitoring | Calculating inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation [27] |

| Standardized Buffers | Consistent sample dilution and matrix conditions | Universal buffer (10 mM PBS, 1% HSA, 0.1% trehalose) for standard preparation [21] |

The persistent challenges of interassay variability and the lack of universal standards remain significant obstacles in viral load quantification and biomarker assessment. The experimental evidence demonstrates substantial variability across different assay systems, which can impact clinical interpretations and research conclusions. However, methodological approaches such as matched pairs analysis, statistical quantification of variability, and the development of universal standards offer promising pathways toward improved harmonization.

The establishment of universal standards for SARS-CoV-2 detection represents a significant advancement in the field, providing a model for standard development for other viral targets. Similarly, regulatory frameworks and quality standards play an essential role in promoting consistency across testing platforms. As research continues to address these challenges, the implementation of standardized reagents, rigorous validation protocols, and transparent reporting of variability metrics will be crucial for enhancing the reliability and correlation of viral load quantification methods across different platforms and laboratories.

From Bench to Bedside: Applied Viral Load Quantification Across Pathogens and Sample Types

Viral infections remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality in transplant recipients, necessitating precise viral load monitoring to guide preemptive therapy and prevent allograft loss. Quantitative nucleic acid testing (QNAT) has become the cornerstone for managing post-transplant viral infections, allowing clinicians to distinguish between latent infection and active disease. This guide objectively compares the quantification methodologies, clinical thresholds, and performance characteristics for four herpesviruses with significant post-transplant implications: cytomegalovirus (CMV), BK polyomavirus (BKV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6). Understanding the correlation between viral load kinetics and clinical outcomes is essential for optimizing patient management in transplant virology.

Viral Load Thresholds and Clinical Correlations

Comparative Analysis of Viral Load Thresholds

Table 1: Clinically Significant Viral Load Thresholds in Transplant Virology

| Virus | Specimen Type | Clinical Threshold | Clinical Correlation | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV | Plasma | 1,700 IU/mL (SOT) [28] | Distinguishes CMV disease from asymptomatic infection [28] | Sensitivity 80%, Specificity 74% (SOT) [28] |

| Plasma | 1,350 IU/mL (HSCT) [28] | Distinguishes CMV disease from asymptomatic infection [28] | Sensitivity 87%, Specificity 87% (HSCT) [28] | |

| Plasma | 830 IU/mL [29] | Treatment initiation threshold | Program-wide standardized threshold [29] | |

| BKV | Plasma | Qualitative NAT+ [30] | Rules out BKVAN | Sensitivity 97.7%, Specificity 90.7%, NPV 99.9% [30] |

| Plasma | >1.0E+04 copies/mL [30] | Predicts BKVAN in viremic patients | Sensitivity 56.3%, PPV 54.6% [30] | |

| EBV | Plasma | Varies by assay [31] [32] | PTLD risk stratification | Qualitative monitoring essential [31] |

| HHV-6 | CSF | Detection alone insufficient [33] | Clinical relevance uncertain | No VL correlation with disease likelihood [33] |

Kinetic Parameters and Clinical Outcomes

Table 2: Viral Load Kinetic Parameters Predicting Adverse Outcomes

| Kinetic Parameter | Clinical Impact | Timeframe | Risk Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| First CMV episode >15 days [29] | Predicts transplant failure | First viremic episode | 3-fold increased risk [29] |

| Maximum CMV VL ≥4.0 log10 IU/mL [29] | Predicts transplant failure | First viremic episode | 3-fold increased risk [29] |

| Recurrent CMV infection [29] | Graft failure and death | Multiple episodes | Progressive risk increase [29] |

| Cumulative viremia duration [29] | Graft failure and death | Entire post-transplant period | Survival declines to 30% [29] |

| Total viral load AUC [29] | Graft failure and death | Entire post-transplant period | Survival declines to 7% [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized CMV Viral Load Testing Protocol

The COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan CMV Test (CAP/CTM CMV) represents the FDA-approved standardized approach for CMV quantification [28]. The assay demonstrates a lower limit of detection (LoD) of 91 IU/mL in plasma, with lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) at 137 IU/mL and upper limit of quantification (ULoQ) at 9,100,000 IU/mL [28].

Sample Processing Protocol:

- Collection: Whole blood collected in EDTA tubes followed by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate plasma [34]

- Extraction Methods Comparison:

- Automatic magnetic bead-based extraction (EZ1 DSP Virus kit/Virus mini kit): Higher throughput with minimal contamination risk [34]

- Manual silica membrane extraction (QIAamp DSP Virus kit): Labor-intensive but effective [34]

- Heating protocol: 90 μL plasma incubated with protease Q at 56°C for 15 min, followed by inactivation at 90°C for 10 min [34]

- Modifications for Whole Blood: Required 1:6 dilution in Specimen Pre-Extraction Reagent, incubation at 56°C for 10 min with shaking at 1000 rpm [28]

- Quantification Correction: Applied -0.43 log10 IU/mL calibration correction factor to log-transformed results [28]

BKV Nucleic Acid Testing Protocol

BKV monitoring employs real-time PCR methodologies with evolving platform technologies [30]. The diagnostic approach differs significantly based on clinical context.

Analytical Performance Characteristics:

- Abbott Alinity m BKV AMPL kit: Demonstrates 96.6% sensitivity in plasma, 95.8% sensitivity in urine, with correlation coefficients of 0.965 (plasma) and 0.971 (urine) compared to reference methods [35]

- Random-access testing: Enables reduced turnaround time between sampling and result availability [35]

Clinical Application Protocol:

- Surveillance context: Negative qualitative NAT during protocol surveillance provides 99.9% negative predictive value for excluding BKVAN at 2.6% prevalence [30]

- Viremic patient context: QNAT exceeding 1.0E+04 BKPyV-DNA copies/mL shows limited predictive value (PPV 54.6%) [30]

EBV and HHV-6 Detection Methodologies

EBV Quantification Advances:

- NeuMoDx EBV Quant Assay 2.0: Automated system demonstrating 95.3% positive percent agreement and 95.1% negative percent agreement with cobas EBV test [32]

- Assay limitations: Increased variability observed at upper and lower limits of dynamic range [32]

HHV-6 Clinical Significance Assessment:

- Retrospective analysis protocol: Review of 8,778 samples from 8,222 individuals between 2010-2021 [33]

- Clinical categorization: HHV-6 detection classified as unlikely (83%), possible (14%), or likely (3%) clinically relevant [33]

- Critical finding: No significant difference in HHV-6 DNA levels between clinical significance categories [33]

Diagnostic Workflow and Clinical Decision Pathways

Post-Transplant Viral Monitoring Algorithm

Diagram 1: Viral monitoring algorithm for CMV management in transplantation. D: Donor, R: Recipient serostatus.

BKV Associated Nephropathy Diagnostic Pathway

Diagram 2: BKV diagnostic pathway highlighting high NPV of qualitative testing.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Transplant Virology

| Reagent/Platform | Virus Target | Function/Application | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAP/CTM CMV Test (Roche) | CMV | FDA-approved CMV quantification in plasma [28] | LoD: 91 IU/mL (plasma), LoD: 240 IU/mL (whole blood) [28] |

| Artus CMV QS-RGQ kit (Qiagen) | CMV | Real-time PCR quantification [34] | Compatible with multiple extraction methods [34] |

| Abbott Alinity m BKV AMPL kit | BKV | Random-access BKV quantification [35] | Sensitivity: 96.6% (plasma), 95.8% (urine) [35] |

| Argene BKV R-gene kit (BioMerieux) | BKV | BKV DNA quantification [30] | Used with Roche LightCycler platforms [30] |

| NeuMoDx EBV Quant Assay 2.0 | EBV | Automated EBV DNA quantification [32] | PPA: 95.3%, NPA: 95.1% [32] |

| EZ1 Advanced XL (Qiagen) | Multiple | Automated nucleic acid extraction [34] | Magnetic bead technology, minimal cross-contamination [34] |

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Multiple | Manual nucleic acid extraction [36] | Silica membrane technology [36] |

| FilmArray ME Panel | HHV-6 | Syndromic testing for CNS infections [33] | Detects HHV-6 but clinical utility questionable [33] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The correlation between viral load kinetics and clinical outcomes in transplant recipients continues to evolve with standardization of quantification methodologies. CMV viral load thresholds have been successfully established for distinguishing disease from infection, with kinetic parameters providing prognostic information about allograft survival [28] [29]. In contrast, BKV monitoring demonstrates exceptional utility for ruling out nephropathy but limited positive predictive value, highlighting the complex relationship between viremia and tissue-invasive disease [30].

The clinical significance of EBV and HHV-6 detection remains more challenging to interpret. While EBV quantification assays continue to improve in performance characteristics [32], the inclusion of HHV-6 in routine diagnostic panels for CNS infections requires reconsideration given the limited clinical relevance in most detection scenarios [33].

Future directions in transplant virology include the investigation of novel biomarkers such as Torque Teno virus (TTV) for immunologic risk stratification [37], the development of standardized extraction methodologies across platforms [34] [35], and the implementation of viral load kinetics as predictive tools for individualizing immunosuppression regimens. The successful integration of viral quantification data into clinical decision-making requires ongoing correlation between laboratory values and patient outcomes, particularly for viruses where therapeutic thresholds remain ill-defined.

The accurate detection and quantification of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) remains a critical component of public health responses and clinical management of COVID-19. While reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) has established itself as the gold standard for diagnostic testing, reverse transcription droplet digital PCR (RT-ddPCR) has emerged as a powerful alternative with potential advantages in specific scenarios. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance characteristics of both platforms in the context of respiratory sample testing, providing researchers and clinicians with evidence-based insights to inform methodological selection for viral load quantification and monitoring.

Fundamental Technological Differences

RT-qPCR is a relative quantification method that measures the amplification of target nucleic acids during PCR cycles in real-time, requiring standard curves for quantification. It has been widely implemented for SARS-CoV-2 detection in clinical and public health laboratories worldwide [11] [38].

RT-ddPCR utilizes a limiting dilution approach where the reaction mixture is partitioned into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, with each droplet functioning as an individual PCR reactor. Following end-point amplification, positive and negative droplets are counted, and the target concentration is absolutely quantified using Poisson statistics without the need for standard curves [11] [38].

Comprehensive Performance Metrics

Table 1: Direct performance comparison between RT-qPCR and RT-ddPCR for SARS-CoV-2 detection

| Performance Parameter | RT-qPCR | RT-ddPCR | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 12.0 copies/μL [39] | 0.066 copies/μL [39] | Wastewater analysis [39] |

| Quantification Approach | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (Poisson statistics) | Multiple studies [11] [38] |

| Precision | Subject to amplification efficiency variations | Coefficient of variation <10% [11] | Serial dilution studies [11] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Moderate | High [38] [40] | Complex matrices comparison [39] [40] |

| Detection in Low Viral Load Samples | 21/50 positive in wastewater [11] | 50/50 positive in wastewater [11] | Wastewater sample analysis [11] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Established [41] [42] | Developing | Clinical validation [41] [42] |

Table 2: Clinical performance comparison in respiratory samples

| Clinical Performance | RT-qPCR | RT-ddPCR | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Detection Rate | 89/130 [43] | 93/130 [43] | 130 clinical samples [43] |

| Suspected Cases | 9/130 [43] | 21/130 [43] | Hospitalized patients [43] |

| Negative Results | 32/130 [43] | 16/130 [43] | Oropharyngeal swabs [43] |

| Coincidence Rate | 98.65% [11] | 98.65% [11] | 148 pharyngeal swabs [11] |

| Kappa Value | 0.94 [11] | 0.94 [11] | Method agreement [11] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative RT-ddPCR Protocol for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

The following protocol was adapted from established methodologies with proven sensitivity and specificity for SARS-CoV-2 variants [11] [44]:

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction:

- Collect respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs) in universal viral transport medium

- Extract RNA using commercial kits (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen)

- Elute RNA in 50 μL nuclease-free water

- Store extracts at -80°C if not used immediately

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare 20 μL reaction mixture containing:

- 5 μL One-Step RT-ddPCR Supermix

- 2 μL primer-probe mix (final concentration: 900 nM primers, 250 nM probe)

- 2 μL reverse transcriptase

- 1 μL 300 mM DTT

- 8 μL nuclease-free water

- 2 μL RNA template

- Primers and probes target SARS-CoV-2 N and S genes [11]

Droplet Generation and Thermal Cycling:

- Generate droplets using automated droplet generator

- Transfer droplets to 96-well PCR plate

- Seal plate and run with following thermal protocol:

- Reverse transcription: 45°C for 60 minutes

- Enzyme activation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing/extension: 53.5°C for 60 seconds

- Enzyme deactivation: 98°C for 10 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

Droplet Reading and Analysis:

- Transfer plate to droplet reader

- Analyze using Poisson statistics to determine absolute copy numbers

- Set fluorescence thresholds based on negative controls

- Report copies/μL of reaction mixture

Representative RT-qPCR Protocol for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare 20-25 μL reaction mixture containing:

- One-Step RT-qPCR master mix

- Primers and probes targeting SARS-CoV-2 genes (N1, N2, E, or ORF1ab)

- 5-10 μL RNA template

- Include appropriate positive and negative controls

Thermal Cycling:

- Reverse transcription: 50°C for 10-30 minutes

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 1-10 minutes

- 40-45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10-15 seconds

- Annealing/extension: 55-60°C for 30-60 seconds

- Data collection during annealing/extension phase

Analysis:

- Determine cycle threshold (Ct) values

- Compare to standard curve for quantification

- Interpret results based on established cutoffs (typically Ct <37-40)

Figure 1: Comparative workflow of RT-qPCR and RT-ddPCR for SARS-CoV-2 detection

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for SARS-CoV-2 detection assays

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products/References |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid purification from clinical samples | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) [11], AllPrep PowerViral DNA/RNA Kit [39] |

| One-Step RT-PCR Master Mixes | Combined reverse transcription and PCR amplification | One-Step RT-ddPCR Advanced Kit for Probes (Bio-Rad) [11], QuantiNova Pathogen Mastermix [40] |

| Primer/Probe Sets | Target-specific amplification and detection | N1, N2, E gene assays [41] [11], ORF1ab gene assays [43] |

| Digital PCR Reagents | Droplet generation and stabilization | Droplet Generation Oil, Droplet Reader Oil [45] |

| Positive Controls | Assay validation and quality control | SARS-CoV-2 RNA standards [40], quantified viral RNA [11] |

| Internal Controls | Monitoring extraction and amplification efficiency | MS2 bacteriophage [41] [40], human RNase P [43] |

Applications and Method Selection Guidelines

Optimal Use Cases for RT-ddPCR

RT-ddPCR demonstrates superior performance in specific scenarios that are particularly relevant to research and advanced clinical applications:

Low Viral Load Detection: Multiple studies have confirmed the advantage of RT-ddPCR in detecting SARS-CoV-2 in samples with low viral loads. In wastewater surveillance, RT-ddPCR detected SARS-CoV-2 in 50/50 samples compared to only 21/50 by RT-qPCR [11]. This enhanced sensitivity makes it invaluable for early infection detection, monitoring treatment response, and discharge testing where residual viral RNA persists at minimal levels.

Absolute Quantification Requirements: When precise viral load quantification is necessary without reliance on standard curves, RT-ddPCR provides absolute quantification that enables more accurate longitudinal monitoring and inter-laboratory comparisons [38]. This is particularly valuable in clinical trials and pathogenesis studies where precise viral kinetics measurement is required.

Complex Matrices: The partitioning technology of ddPCR enhances tolerance to PCR inhibitors commonly found in complex sample types, including wastewater, saliva, and certain respiratory specimens [39] [38]. This reduces false-negative results and improves reliability in environmental surveillance and alternative sample testing.

Optimal Use Cases for RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR remains the preferred method for many routine applications due to its established infrastructure and practical advantages:

High-Throughput Diagnostic Testing: For large-scale screening and routine diagnostic applications where rapid turnaround time is essential, RT-qPCR offers established workflows, higher throughput capacity, and lower per-sample costs [41]. The extensive validation and standardization of RT-qPCR protocols support its continued use in clinical diagnostics.

Multiplex Assays: RT-qPCR has well-established capabilities for multiplex detection of multiple pathogens in a single reaction [41] [42]. Recently developed multiplex assays simultaneously detect SARS-CoV-2, influenza A/B, and other respiratory pathogens with high sensitivity and specificity [42] [46], providing comprehensive respiratory pathogen testing.

Resource-Limited Settings: The wider availability of instrumentation, lower reagent costs, and established regulatory frameworks make RT-qPCR more accessible for routine clinical use and resource-limited settings [42].

Both RT-qPCR and RT-ddPCR offer distinct advantages for SARS-CoV-2 detection in respiratory samples. RT-qPCR remains the workhorse for high-throughput diagnostic testing due to its established infrastructure, rapid turnaround times, and cost-effectiveness. In contrast, RT-ddPCR provides enhanced sensitivity and absolute quantification benefits that are particularly valuable for research applications, low viral load detection, and precise viral load monitoring. The selection between these platforms should be guided by specific application requirements, with RT-ddPCR offering complementary capabilities that address specific limitations of conventional RT-qPCR, particularly in surveillance and research contexts where maximum sensitivity and precise quantification are paramount.

The accurate quantification of HIV-1 viral load is a cornerstone for monitoring antiretroviral therapy efficacy and achieving global treatment targets. While plasma-based viral load testing remains the gold standard, dried blood spot (DBS) sampling has emerged as a pivotal alternative for expanding access to virological monitoring, particularly in resource-limited settings. This guide provides a comprehensive, data-driven comparison of the performance characteristics of DBS versus plasma for HIV-1 RNA quantification. We synthesize recent evidence on correlation strength, quantitative bias, and diagnostic concordance from field evaluations across multiple countries and assay platforms. Furthermore, we detail standardized experimental protocols for sample processing and analysis, visualize methodological workflows, and catalog essential research reagents. This objective analysis aims to inform researchers, scientists, and program implementers on the appropriate applications and limitations of DBS within viral load quantification method correlation research.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: DBS vs. Plasma

Extensive research has demonstrated that DBS samples produce quantitatively comparable results to plasma, albeit with a consistent, measurable bias. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Summary of Quantitative Correlation from Recent Studies

| Study Location & Citation | Sample Size (n) | Assay Platform | Mean Log Difference (DBS - Plasma) | Correlation Coefficient (r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northwest Ethiopia [16] [47] | 48 | Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan v2.0 | +0.66 ± 0.70 log copies/mL | 0.796 (p < 0.001) |

| India (South) [48] | 62 | Abbott RealTime HIV-1 PCR | -0.41 log copies/mL | 0.982 (p < 0.0001) |

The data indicates a strong positive correlation between DBS and plasma viral load measurements, though the direction and magnitude of the mean log difference can vary. The Ethiopian study reported DBS viral loads were, on average, 0.66 log copies/mL higher than paired plasma measurements [16]. In contrast, the study from India found DBS measurements to be slightly lower [48]. This underscores the importance of platform-specific and context-specific validation.

Table 2: Operational and Diagnostic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Plasma (Gold Standard) | Dried Blood Spot (DBS) |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume | Larger volumes required (e.g., 1 mL for plasma harvest from 4 mL whole blood) [16] | Minimal volume (e.g., ~50 µL spotted onto filter paper) [16] |

| Stability & Transport | Requires cold chain (freezing at -20°C) for storage and transport [16] | Stable at room temperature for extended periods; ease of transport via mail [16] [49] |

| Concordance for Recent Infection (Zimbabwe) [50] [51] | 10.1% (47/464) classified recent | 12.3% (57/464) classified recent |

| Overall Categorical Agreement (Zimbabwe) [50] | - | 97.4% (452/464) with plasma |

For classifying recent infections, DBS and plasma show high categorical agreement, though slight differences in classification rates exist. In a large study in Zimbabwe, DBS assigned a slightly higher proportion of samples as recent compared to plasma (12.3% vs. 10.1%), with an overall concordance of 97.4% for recent/long-standing classification [50] [51].

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

To ensure valid and reproducible comparisons between DBS and plasma viral load measurements, adherence to standardized experimental protocols is critical. The following section details the key methodologies cited in recent literature.

Sample Collection and Processing

The foundational step involves the paired collection of venous blood for both sample types from study participants.

- Whole Blood Collection: A total of 4 mL of venous blood is collected into a vacutainer tube containing EDTA anticoagulant [16].

- Plasma Harvesting: Plasma is separated from whole blood via centrifugation, typically at 2500 RPM for 10 minutes. The harvested plasma is then aliquoted into cryovials [16].

- DBS Preparation: Approximately 50 µL of whole blood is dispensed onto each of five circles on a Whatman 903 filter paper card. The spots are air-dried at room temperature for 4-6 hours [16].

- Storage: Plasma aliquots are stored frozen at -20°C until testing. DBS cards are placed in zip-lock plastic bags with silica gel desiccant pouches and can be stored at -20°C or, for shorter periods, at room temperature [16].

HIV-1 RNA Extraction and Quantification

The Roche COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan system provides an automated platform for processing both sample types, as described in the Ethiopian study [16].

RNA Extraction:

- Plasma: A 1100 µL aliquot of plasma is loaded into the COBAS AmpliPrep instrument for automated RNA extraction, which is based on the silica-based capture principle [16].

- DBS: Two half-spots (6 mm in diameter) are punched out from the DBS card using a clean forceps and transferred to a lysis solution. The same automated extraction process on the COBAS AmpliPrep is then followed [16].

- A known concentration of HIV-1 Quantitation Standard (QS) RNA is added to both sample types to monitor extraction efficiency and act as an internal control [16].