Viral Morphology Unveiled: A Comprehensive Guide to Electron Microscopy Techniques and Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electron microscopy (EM) techniques for analyzing viral morphology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Viral Morphology Unveiled: A Comprehensive Guide to Electron Microscopy Techniques and Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electron microscopy (EM) techniques for analyzing viral morphology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of EM in virology, details established and cutting-edge methodological applications, offers practical troubleshooting guidance, and discusses validation frameworks and comparative analyses with other structural biology tools. The content synthesizes current advancements, including cryo-electron microscopy's revolutionary role in structure-based drug design, to serve as a essential resource for viral pathogen research and therapeutic development.

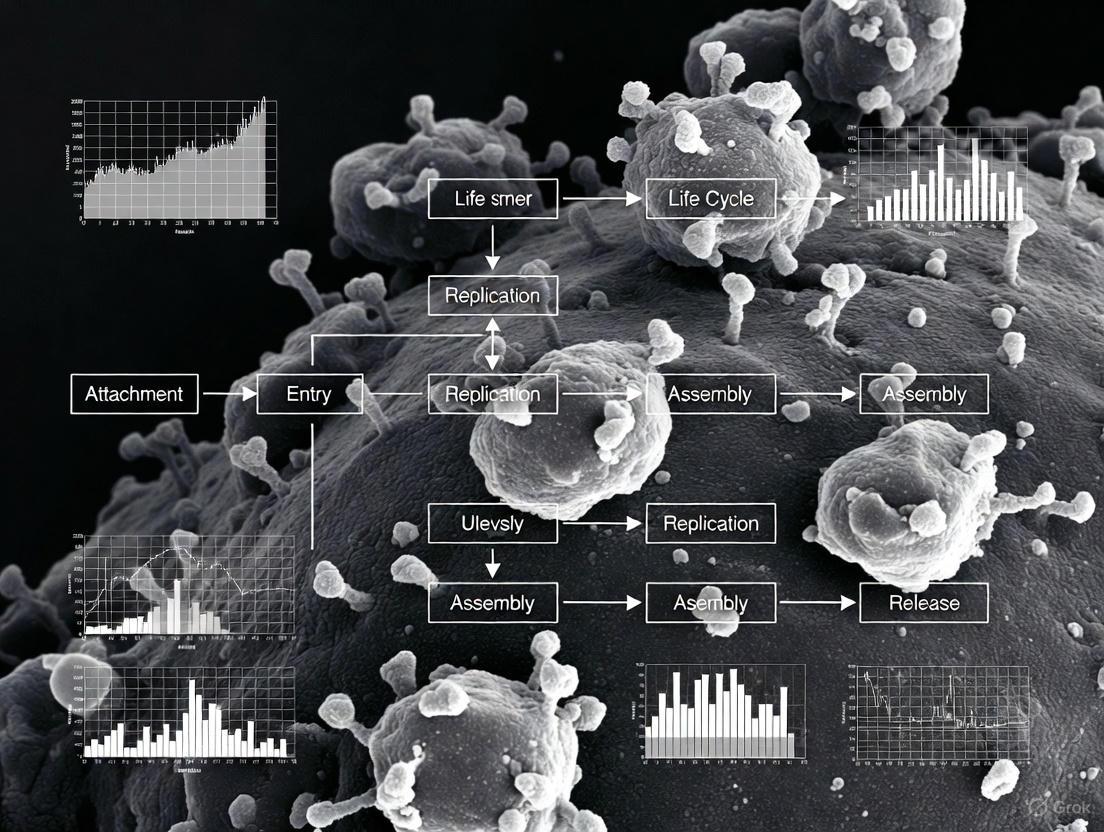

The Foundation of Viral Visualization: How Electron Microscopy Reveals Pathogen Architecture

Electron microscopy (EM) has served as a cornerstone technique in virology, providing the first visual evidence of viruses and enabling their classification based on ultrastructural morphology. Since its development in the 1930s, EM has made possible the direct visualization of viral particles, which are too small to be resolved by light microscopy [1] [2]. This capability has been instrumental in the discovery of many clinically significant viruses and has fundamentally shaped our understanding of virus-host cell interactions. Although partly supplanted by molecular techniques for routine diagnosis, EM remains indispensable for the initial identification of unknown viral agents, investigation of viral morphogenesis, and ensuring the viral safety of biological products [1] [3]. This article outlines the critical historical milestones of EM in virology and provides detailed protocols for its application in modern viral research.

Historical Milestones in Viral Discovery

The application of electron microscopy to virology has marked several transformative periods in science history, characterized by technological innovations that expanded our capacity to identify and characterize viral pathogens.

The Early Developments

The transmission electron microscope (TEM), initially described as a "supermicroscope" by Max Knoll and Ernst Ruska in 1932, provided a resolution far exceeding that of light microscopes available at the time [1] [2] [4]. The first documented use of TEM in clinical virology was for the differential diagnosis of smallpox and chickenpox using vesicle fluid from patients' skin, demonstrating its diagnostic potential from the outset [1] [2].

The Golden Age of Virus Discovery

The period from the 1960s to the 1980s represented the "glory days" for viral EM, fueled by the widespread commercial availability of electron microscopes and the introduction of negative staining techniques [1]. This simple yet powerful method, involving the deposition of viral samples on carbon-coated grids stained with heavy-metal salts, enabled rapid visualization and morphological analysis of viruses from liquid samples [1] [3]. This era witnessed the discovery and classification of numerous virus families, including adeno-, entero-, paramyxo-, and reoviruses [1]. The application of EM to "dirty" clinical samples like plasma, urine, and feces led to major breakthroughs, including the identification of:

- Hepatitis B virus (Dane et al., 1970) in plasma [1] [2]

- Hepatitis A virus (Feinstone et al., 1973) in stool samples [1] [2]

- Rotaviruses (Bishop et al., 1973; Flewett et al., 1973) as a primary cause of gastroenteritis [1] [2]

- Norwalk virus (Kapikian et al., 1972), later renamed norovirus [1] [2]

Table 1: Major Virus Discoveries Enabled by Electron Microscopy

| Virus | Year Identified | Sample Source | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B | 1970 | Plasma | First visualization of the hepatitis B virion (Dane particle) [1] |

| Rotavirus | 1973 | Stool | Identified as major cause of epidemic gastroenteritis in humans and animals [1] |

| Norwalk Virus | 1972 | Stool | First identification during community outbreak of gastroenteritis [1] |

| Parvovirus B19 | 1975 | Serum | Discovered during search for hepatitis B virus [1] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 2020 | Cell Culture | Rapid identification during COVID-19 pandemic [5] [6] |

Modern Applications and Emerging Techniques

While molecular methods like PCR and ELISA largely replaced TEM for routine viral diagnosis due to their higher sensitivity, EM retains crucial roles in virology [1] [3]. It remains the premier "catch-all" method for identifying unknown or emerging pathogens in outbreak situations, as demonstrated during the discoveries of the Hendra virus (1995), Nipah virus (1999), and the SARS coronavirus (2003) [1] [2]. Furthermore, regulatory agencies recommend TEM for investigating the viral safety of biological therapeutics, and it remains essential in research for discriminating between aggregated proteins and structured viral particles [1].

Modern advancements continue to expand EM's capabilities. Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM) combines fluorescence microscopy with EM, allowing researchers to bridge the resolution gap between these techniques [7]. Energy-Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis integrated with EM enables elemental mapping, adding a "color" dimension to traditional grey-scale EM images and allowing identification of organelles and molecules based on their elemental composition [8]. Additionally, machine learning approaches are now being developed for unsupervised classification of viral surface spikes in EM images, enhancing the objectivity and reproducibility of morphological analyses [9].

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

The two principal techniques for viral detection by EM are negative staining of suspensions and thin-section EM of resin-embedded samples. These robust and reliable methods have remained largely unchanged for decades, ensuring consistency with a vast repository of historical reference data [3].

Negative Staining for Rapid Viral Identification

Negative staining is a quick technique for visualizing viral particles in liquid samples, ideal for rapid diagnostics and particle enumeration [3].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Negative Staining EM

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Formvar or Pioloform-filmed EM Grids (300-400 mesh) | Sample support | Provides an electron-transparent film for particle adsorption [3] |

| Alcian Blue, Poly-L-lysine, or Bacitracin | Grid surface conditioning | Renders the grid surface hydrophilic and sticky for efficient particle adsorption [3] |

| Uranyl Acetate or Phosphotungstic Acid | Heavy metal stain | Embeds and contrasts viral particles; creates negative image [3] |

Protocol: Negative Staining for Viral Particles

- Grid Preparation: Condition EM grids by applying a charged surface. This can be achieved either by glow discharge or by chemical treatment with Alcian blue, which is robust and efficient for adsorbing particles [3].

- Sample Adsorption: Apply a small volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the viral suspension to the pre-treated grid surface. Two primary methods are used:

- Drop-On-Grid (DOG): Place the sample droplet directly on the grid. This is more effective for dense particles like bacteria or poxviruses [3].

- Grid-On-Drop (GOD): Float the grid on a droplet of the suspension. This can help reduce the adsorption of larger, irrelevant particles that may sediment away from the grid surface [3].

- Washing: Briefly rinse the grid with a drop of distilled water to remove salts and other soluble contaminants. Carefully blot away excess liquid with filter paper.

- Staining: Apply a drop of heavy metal stain (e.g., 1-2% uranyl acetate or phosphotungstic acid) to the grid for seconds to minutes. Blot away the excess stain to leave a thin, amorphous layer embedding the viral particles [3].

- Visualization: Air-dry the grid and examine using a transmission electron microscope operating at 80-100 kV.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the negative staining protocol:

Diagram 1: Negative Staining Workflow

Thin-Section EM for Intracellular Viral Analysis

Thin-section EM allows for the visualization of viral particles within the cellular context, revealing details about viral replication, assembly, and virus-host interactions [5] [6].

Protocol: Thin-Section EM for Infected Cell Cultures

- Cell Culture and Infection: Grow susceptible cells (e.g., Vero E6 cells for SARS-CoV-2) to 70-80% confluence and infect with the virus at a desired multiplicity of infection (MOI) [5].

- Fixation: At the appropriate time post-infection, replace the culture medium with a primary fixative, typically 2.5% glutaraldehyde in a buffer (e.g., 0.05 M HEPES, pH 7.2). Fix for at least 1 hour at room temperature [5].

- Post-Fixation and Staining: Post-fix with 1% osmium tetroxide to stabilize lipids and provide contrast. This step is critical for visualizing membrane structures.

- Dehydration and Embedding: Dehydrate the fixed cell pellet through a graded series of ethanol or acetone, followed by infiltration and embedding with a resin, such as Epon or Araldite [5] [8].

- Sectioning and Staining: Use an ultramicrotome to cut ultrathin sections (60-90 nm) of the embedded block. Mount sections on EM grids and stain with heavy metal stains like uranyl acetate and lead citrate to enhance contrast [5].

- Visualization: Examine the stained sections using a transmission electron microscope.

The following workflow summarizes the thin-section EM protocol:

Diagram 2: Thin-Section EM Workflow

Quantitative Morphology in Modern Virology

EM morphometry provides quantitative data on viral parameters such as size and spike density, which can be correlated with viral properties like transmissibility.

Case Study: Morphometric Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Variants

A 2024 study performed a detailed morphometric analysis of major SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern (VOCs) using thin-section EM, demonstrating the continued value of quantitative EM in virology [5].

Table 3: Morphometric Parameters of SARS-CoV-2 Variants from Thin-Section EM

| SARS-CoV-2 Variant | Maximum Particle Diameter (nm) | Spike Number per Virus Profile | Notable Morphometric Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Strains (e.g., Munich929) | Baseline | Baseline | Used as reference for comparison [5] |

| Alpha (B.1.1.7) | Slightly smaller | Slightly increased | Dominant variant with increased spike density [5] |

| Beta (B.1.351) | Larger | Reduced | Less dominant variant with reduced spike density [5] |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) | Slightly smaller | Slightly increased | Dominant variant with increased spike density [5] |

| Omicron BA.2 (B.1.1.529) | Slightly smaller | Slightly increased | Dominant variant with increased spike density [5] |

The study noted that the more dominant variants (Alpha, Delta, Omicron) tended to show a slightly increased spike density, often associated with a smaller particle size. In contrast, the less dominant Beta variant exhibited a reduced spike density and a larger particle size [5]. These findings highlight how EM-derived morphometric data can contribute to understanding phenotypic differences between viral variants.

From its foundational role in the discovery and classification of major viral pathogens to its modern applications in characterizing emerging viruses and quantifying phenotypic traits, electron microscopy has been an indispensable tool in virology. While its diagnostic role has evolved, EM remains unmatched for direct, morphology-based viral identification, investigation of virus-cell interactions, and safety testing. The integration of EM with advanced elemental analysis, correlative techniques, and machine learning promises to further enhance its power, ensuring that electron microscopy will continue to be a vital technology for virologists and drug development professionals confronting current and future viral challenges.

Electron microscopy (EM) has become an indispensable tool in viral morphology research and drug development, enabling scientists to visualize pathogens and cellular structures at nanometer resolution. The power of EM to inform vaccine design and therapeutic strategies, as demonstrated during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, hinges on a solid understanding of its core physical principles [5]. For researchers investigating viruses, mastering these fundamentals is not merely academic—it directly impacts the quality of structural data, the accuracy of pathogen identification, and the validity of subsequent scientific conclusions. This application note details the essential concepts of resolution and contrast, provides practical protocols for viral imaging, and establishes rigorous criteria for morphological analysis to ensure research reproducibility and reliability in viral studies.

Resolution in Electron Microscopy

Definition and Determinants

Resolution in electron microscopy refers to the smallest distance between two points that can still be distinguished as separate entities in the resulting image. For viral research, this determines the level of structural detail observable, from overall virion shape down to individual spike proteins. The resolution revolution, driven primarily by the development of direct electron detectors, has transformed cryo-EM from a niche technique to a powerhouse capable of determining biomolecular structures at near-atomic resolution [10].

The theoretical and practical limits of resolution are governed by several key factors:

- Electron wavelength: Determined by the accelerating voltage of the microscope

- Lens aberrations: Imperfections in the electromagnetic lenses that deflect electrons

- Signal-to-noise ratio: Influenced by electron dose, detector efficiency, and sample properties

Table 1: Key Resolution Capabilities Across EM Modalities

| Technique | Typical Practical Resolution | Optimal Use Cases in Virology |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Stain TEM | 15-20 Å | Rapid viral detection, particle counting |

| Thin-Section TEM | 10-15 Å | Intracellular viral localization |

| Cryo-EM Single Particle | 2-3 Å | Atomic structure determination |

| Cryo-Electron Tomography | 3-5 Å | Viral architecture in situ |

The Resolution Revolution and Current Trends

The 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry recognized the transformative impact of improved cryo-EM resolution, attributed largely to direct electron detectors that capture images with significantly enhanced resolution compared to previous technologies that converted electrons to light [10]. Current research focuses on making high-resolution cryo-EM more accessible through lower-voltage (100 keV) instruments that maintain image quality while reducing costs, potentially democratizing the technique for broader research community access [10].

Contrast Mechanisms in Electron Microscopy

Physical Principles of Contrast Generation

Contrast is the difference in signal intensity between a feature of interest and its surroundings in an image. For biological samples like viruses, which consist primarily of low-atomic-number elements, generating sufficient contrast presents a particular challenge. In the absence of a sample, an electron beam would produce a uniformly gray micrograph, with minimal variation between pixels [11]. Biological samples introduce local variations in electron scattering that create the image contrast necessary for visualization.

Two primary mechanisms generate contrast in electron micrographs of viral samples:

Amplitude Contrast

Amplitude contrast arises when electrons are absorbed, deflected, or otherwise blocked by the sample, reducing the amplitude of the electron wave that reaches the detector [11]. While heavy atoms used in negative staining deflect a large proportion of the incoming electron beam, creating excellent amplitude contrast, this mechanism plays a negligible role for unstained biological macromolecules in cryo-EM because proteins and the surrounding aqueous buffer contain atoms with similar atomic numbers [11]. A notable exception occurs with nucleic acids, which contain heavier phosphorus atoms that generate slightly higher amplitude contrast [11].

Phase Contrast

The vast majority of contrast in cryo-EM comes from phase contrast [11]. Biological samples are primarily "phase objects" that delay the electron wave rather than absorbing it, creating a phase shift between incoming and exiting waves [11]. Since detectors record intensity (the square of amplitude) rather than phase, pure phase objects would normally be invisible. Contrast generation requires the microscope to be configured to convert these phase shifts into detectable amplitude variations through interference between scattered and unscattered waves [11].

Phase Contrast Generation Pathway: This diagram illustrates the transformation of initially invisible phase shifts into detectable contrast through intentional defocus or phase plate technology.

The Weak Phase Object Approximation

For most biological samples including viruses, the weak phase object approximation provides a practical model for understanding contrast formation [11]. This approximation assumes that the sample only scatters a small proportion of the incoming electron wave, with the scattered wave experiencing a constant phase shift of exactly π/2 [11]. The exit wave is therefore modeled as the sum of the incoming wave and this small, phase-shifted scattered component. Under ideal focused conditions, the phase shift renders phase objects invisible in the final image, necessitating specialized techniques to convert these phase shifts into detectable amplitude variations [11].

Enhancing Contrast for Biological Samples

Defocus-Controlled Phase Contrast

Collecting images intentionally out of focus introduces additional path length differences between scattered and unscattered electrons, converting phase information into detectable amplitude contrast [11]. As electrons travel from the sample, those scattered at different angles take different paths to reach the same point on the detector, creating phase shifts through path length differences. At specific defocus values, these path length differences produce constructive or destructive interference that transforms phase variations into measurable intensity differences in the image [11].

Chemical Staining for Conventional EM

In conventional transmission electron microscopy of thin sections, heavy metal stains provide essential contrast by binding to cellular structures and viruses. The efficiency of a stain depends primarily on the atomic weight of its constituent atoms, with uranium (atomic weight 238) and lead being the most widely used for their high electron density [12].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for EM Contrast Enhancement

| Reagent | Composition | Primary Applications | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uranyl Acetate | Aqueous or alcoholic solution of U(C₂H₃O₂)₂·2H₂O | Membrane contrast, nucleic acids | Binds to proteins, lipids, nucleic acid phosphate groups |

| Lead Citrate | Alkaline solution of lead citrate | General contrast enhancement, ribosomes | Interacts with proteins, glycogens, and reduced osmium |

| Reynold's Lead Citrate | Lead nitrate + sodium citrate | Standard double staining protocol | Forms lead citrate in situ for consistent staining |

| Alcian Blue | Copper phthalocyanine | Grid surface treatment | Adds charge to support film for better particle adsorption |

Double contrasting with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate represents the standard routine technique for conventional TEM, providing comprehensive structural visualization of viral components and cellular ultrastructure [12]. Uranyl acetate produces the highest electron density and fine grain image quality, particularly for membranes and nucleic acids, while lead citrate enhances a wider range of cellular structures including ribosomes, lipid membranes, and cytoskeletal elements [12].

Imaging Techniques and Protocols for Virology

Sample Preparation Methods

Proper sample preparation is critical for preserving viral structure and generating interpretable images. The choice of preparation method depends on research objectives, whether for rapid diagnostic identification or high-resolution structural analysis.

Negative Staining Protocol for Viral Detection

Negative staining provides a rapid technique for visualizing viral particles in suspensions such as body fluids, stool specimens, or cell culture supernatants [13] [3]. This method is particularly valuable for detecting emerging viral pathogens and in surveillance of potential bioterrorism agents when specific molecular reagents may be unavailable [13].

Materials Required:

- Formvar or Pioloform-coated EM grids (300-400 mesh)

- Alcian blue or other surface charge treatment

- 2% uranyl acetate or 2% phosphotungstic acid

- Patient sample or viral culture supernatant

Procedure:

- Grid Preparation: Treat grids with Alcian blue (0.1% in water) for 10 seconds to create a charged, hydrophilic surface for optimal particle adsorption [3].

- Particle Adsorption: Apply sample to grid using either Drop-On-Grid (DOG) or Grid-On-Drop (GOD) method, incubating for 30-60 seconds [3].

- Washing: Briefly rinse grid with distilled water to remove salts and soluble contaminants.

- Staining: Apply heavy metal stain (uranyl acetate) for 10-30 seconds, then blot excess liquid [3].

- Air Drying: Allow grid to dry completely before EM examination.

For low-concentration samples, ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 30-50 minutes) can pellet viruses from larger volumes (2-8 ml) before resuspension in a small volume for staining [13].

Thin-Section EM for Intracellular Viruses

Thin-section transmission electron microscopy remains invaluable for studying viral pathogenesis within cellular contexts, particularly for complex samples where cryo-techniques face throughput limitations [5] [3].

Materials Required:

- Infected cell cultures or tissue samples

- Glutaraldehyde (2.5%) and paraformaldehyde (1-4%) in buffer

- Osmium tetroxide (1%) for post-fixation

- Ethanol or acetone series for dehydration

- Epoxy resin (Epon, Glycid ether 100) for embedding [14]

- Uranyl acetate and lead citrate for staining [12]

Procedure:

- Primary Fixation: Fix samples with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.05M HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) for at least 1 hour at room temperature [5].

- Post-fixation: Treat with 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer for 1 hour.

- Dehydration: Sequential ethanol dehydration (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%).

- Embedding: Infiltrate with epoxy resin mixture (e.g., Glycid ether 100, DDSA, NMA with DMP-30 catalyst) [14] and polymerize at 60°C for 48 hours.

- Sectioning: Cut ultrathin sections (60-90 nm) using an ultramicrotome.

- Contrasting: Double-stain with uranyl acetate and lead citrate [12].

Viral Sample Preparation Workflow: Two primary pathways for preparing biological samples for electron microscopy, each optimized for different research questions.

Advanced Imaging Modalities

Cryo-Electron Microscopy

Cryo-EM involves rapidly freezing samples to cryogenic temperatures (-196°C) so quickly that water molecules don't crystallize, preserving biological structures in a near-native state [10]. This technique has become essential for high-resolution structural virology, enabling atomic-level analysis of viral components without the artifacts introduced by chemical fixation, dehydration, and staining.

Cryo-Electron Tomography

Cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) represents an advanced technique that builds 3D images of cellular volumes by acquiring multiple tilted views of a sample [10]. When combined with cryo-focused ion beam (cryo-FIB) milling, which prepares thin lamella from cellular samples, cryo-ET can visualize viral architecture within the cellular context at molecular resolution [10]. This approach provides unprecedented insights into virus-host interactions and the spatial organization of viral replication machinery.

Application to Viral Morphology Research

Criteria for Authentic Viral Identification

The resurgence of EM during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic revealed widespread misinterpretation of cellular structures as viral particles, highlighting the need for rigorous identification criteria [15]. To ensure accurate viral identification, researchers should apply the following standards:

Structural Criteria: Viral particles must conform to established morphological characteristics including size, uniformity, and internal structure. For coronaviruses, this includes an approximate diameter of 80 nm (though measured averages may be smaller, e.g., 64 nm for SARS-CoV-2), characteristic dot-like electron densities in the nucleocapsid, and presence within membrane-bound compartments [15].

Locational Criteria: Particles should appear in biologically plausible locations consistent with the viral replication cycle. For coronaviruses, this includes presence within the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment, secretory vesicles, or outside cells—but not free in the cytoplasm [15].

Corroborative Evidence: EM findings should be supported by independent methods such as PCR, immunohistochemistry, or in situ hybridization [15].

Expert Validation: Interpretation should involve experienced electron microscopists familiar with both viral morphology and potential cellular mimics [15].

Morphometric Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Variants

Conventional thin-section EM has proven valuable for tracking morphological changes in evolving viruses. A comprehensive study of SARS-CoV-2 variants revealed subtle but potentially significant differences in particle morphology:

Table 3: Morphometric Parameters of SARS-CoV-2 Variants from Thin-Section EM

| Variant | Maximum Particle Diameter | Spike Number/Density | Notable Morphological Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Munich929 (reference) | Baseline | Baseline | Reference strain for comparison |

| Italy-INMI1 (reference) | Baseline | Baseline | Early pandemic isolate |

| Alpha (B.1.1.7) | Slightly smaller | Slightly increased | Smaller particle size contributes to higher spike density |

| Beta (B.1.351) | Larger | Reduced | Reduced spike number per particle profile |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) | Slightly smaller | Slightly increased | Trend toward compact virions |

| Omicron BA.2 (B.1.1.529) | Slightly smaller | Slightly increased | Maintains trend of dominant variants |

These morphometric data, collected from approximately 900 TEM images under standardized conditions, provide a reference database for analyzing future viral variants and may correlate with epidemiological behavior [5]. The dominant variants (Alpha, Delta, Omicron) consistently showed slightly increased spike density compared to reference strains, primarily due to reduced particle size [5].

Mastering the core principles of resolution and contrast is fundamental to effective electron microscopy in viral research. The interplay between theoretical concepts and practical implementation directly impacts the quality and interpretation of structural data from viral samples. As EM technologies continue evolving toward greater accessibility and higher throughput [10], these fundamentals will remain essential for designing robust experiments, accurately identifying viral pathogens, and deriving meaningful structural insights to inform therapeutic development. By adhering to rigorous protocols and validation criteria, researchers can leverage the full potential of electron microscopy to advance our understanding of viral morphology and pathogenesis.

Viral taxonomy is the process of naming viruses and placing them into a taxonomic system based on phenotypic characteristics, including morphology, nucleic acid type, mode of replication, and host organisms [16]. The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) is the official body responsible for developing and maintaining a universal virus taxonomy [17]. While genomic data now plays a primary role in classification, structural characteristics observed through techniques like electron microscopy remain fundamental for distinguishing major viral groups and understanding their evolutionary relationships.

The structural diversity of viruses provides critical criteria for their classification into higher-level taxa. The presence or absence of a viral envelope, the symmetry of the capsid (icosahedral or helical), and the detailed architecture of structural proteins form the basis for distinguishing viral orders, families, and genera [16] [18]. These morphological features directly influence viral stability, pathogenicity, and infection mechanisms, making them essential considerations for both taxonomic classification and antiviral development [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Virus Classification Systems

| Classification Type | Basis of Classification | Major Categories | Application in Virology |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICTV Taxonomic Structure | Phenotypic characteristics, morphology, nucleic acid, host organisms | Realm, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species [16] | Official universal taxonomic scheme for all viruses [17] |

| Baltimore Classification | mRNA synthesis mechanism, nucleic acid type | 7 Groups (I: dsDNA to VII: dsDNA-RT) [16] | Understanding replication strategies and gene expression |

| Structural Morphology | Capsid symmetry, envelope presence, virion architecture | Icosahedral, helical, complex; enveloped vs. non-enveloped [18] | Linking structure to function, stability, and infection mechanisms |

Structural Features in Virus Classification

Viral Envelopes and Their Taxonomic Significance

Viral envelopes are outermost lipid bilayers derived from host cell membranes (phospholipids and proteins) but incorporate virus-coded glycoproteins [20] [18]. These envelopes are acquired during viral maturation through the process of "budding" at host cell membranes—some at the plasma membrane, others at internal cell membranes such as the nuclear membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi complex [18]. The presence of an envelope represents a major taxonomic character that distinguishes entire viral families.

Enveloped viruses display distinct biological properties that influence their taxonomy, pathogenicity, and environmental stability. The envelopes typically contain viral glycoprotein peplomers (spikes) that project from the outer surface, which mediate host cell recognition, receptor binding, and membrane fusion during infection [20] [18]. These glycoproteins serve as primary antigens for immune recognition and are major targets for vaccine development [20]. Enveloped viruses are generally more sensitive to desiccation, heat, and disinfectants like detergents and alcohols compared to non-enveloped viruses, as these agents disrupt the essential lipid membrane [19]. From a taxonomic perspective, the specific composition and structure of envelope proteins help define viral families and genera, with some families containing multiple envelope glycoproteins (e.g., Herpesviridae with more than 10 glycoproteins) while others have simpler envelope structures [18].

Capsid Symmetry and Structural Families

The viral capsid is a protein shell that encapsulates and protects the genetic material of all viruses. Capsids display two fundamental structural patterns with taxonomic significance: icosahedral symmetry and helical symmetry. Icosahedral capsids form quasi-spherical structures with defined axes of symmetry, while helical capsids form rod-shaped or filamentous structures with the genetic material coiled inside [21] [18].

Icosahedral capsids are constructed from repeating capsomeres arranged with pseudo-T = 3 symmetry in many viruses, particularly positive-sense RNA viruses like picornaviruses [21]. The capsid proteins of many icosahedral viruses feature the jelly roll motif, a conserved β-sandwich fold composed of two antiparallel four-stranded β-sheets named BIDG and CHEF [21]. This structural motif appears across diverse virus families infecting hosts from different domains of life, suggesting ancient evolutionary relationships [16]. For instance, the jelly roll motif is observed in the capsid proteins of both single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses such as Parvoviridae and Circoviridae, and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses including Adenoviridae and Caudoviricetes [22].

Helical capsids are characterized by capsomeres arranged in a spiral around the viral nucleic acid, forming tubular structures that may be rigid or flexible. These are predominantly found in negative-sense RNA viruses and some positive-sense RNA viruses, including plant viruses like Tobamoviruses and animal viruses like Orthomyxoviruses and Rhabdoviruses [18]. The distinction between these capsid symmetries forms a primary morphological division in virus taxonomy, with the ICTV recognizing structure-based viral lineages that reflect evolutionary relationships observed across viruses infecting different domains of life [16].

Table 2: Structural Characteristics of Major Virus Groups

| Structural Feature | Taxonomic Distribution | Key Structural Components | Functional & Taxonomic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Envelope | Found in diverse taxa: Herpesviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Retroviridae, Coronaviridae | Host-derived lipid bilayer + viral glycoproteins (peplomers/spikes) [18] | Increased sensitivity to disinfectants; more complex entry mechanisms; mediates immune evasion |

| Icosahedral Capsids | Caudoviricetes, Picornaviridae, Parvoviridae, Adenoviridae | Jelly roll motif capsid proteins; pseudo-T=3 symmetry [21] | Evolutionary relationships across domains of life; efficient genome packaging; receptor binding sites |

| Helical Capsids | Tobamoviruses, Orthomyxoviridae, Rhabdoviridae | Repeated protein subunits arranged around nucleic acid [18] | Often enveloped in animal viruses; rod-shaped/filamentous morphology; genome length determines particle size |

| Pleomorphic Virions | Thalassapleoviridae, some Paramyxoviridae | Less structured organization; variable shape and size [23] | Challenges in structural characterization; adaptation to specialized niches |

Application Notes: Electron Microscopy for Viral Morphology

Cryo-Electron Microscopy for Capsid Architecture

Purpose: To determine high-resolution structures of viral capsids in near-native states, enabling classification based on structural features and identification of novel taxonomic relationships.

Protocol:

- Virus Purification: Purify virus samples using ultracentrifugation in sucrose or cesium chloride density gradients to isolate intact virions from cellular components [21].

- Vitrification: Apply 3-5 μL of purified virus suspension (≥10^9 particles/mL) to glow-discharged holey carbon grids. Blot excess liquid and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen to form amorphous ice [21].

- Data Collection: Collect micrographs using a 300 keV cryo-electron microscope with a direct electron detector. Use defocus range of -1.0 to -2.5 μm and total dose of 40-60 e⁻/Ų with frame-based exposure [21].

- Image Processing:

- Perform motion correction and dose-weighting of movie frames

- Use reference-free 2D classification to identify particle views and remove damaged particles

- Apply 3D classification to separate heterogeneous populations (virions, empty particles, altered particles)

- Reconstruct final maps using 3D auto-refinement with imposed icosahedral symmetry [21]

- Model Building: Build atomic models into cryo-EM density maps using iterative rounds of manual building in Coot and real-space refinement in Phenix [21].

Expected Outcomes: Determination of capsid architecture at 2.5-4.0 Å resolution, enabling visualization of capsid protein folds, genome packaging, and conformational states relevant for taxonomic classification.

Negative Stain EM for Rapid Envelope Characterization

Purpose: To quickly assess viral morphology, envelope presence, and surface projections for initial taxonomic grouping and sample quality evaluation.

Protocol:

- Grid Preparation: Apply 5 μL of virus suspension to glow-discharged carbon-coated grids for 60 seconds.

- Staining: Blot excess liquid and apply 5-10 μL of 2% uranyl acetate for 30-45 seconds. Blot thoroughly and air dry.

- Imaging: Collect images at 40,000-80,000x magnification using a 120 keV TEM. Acquire multiple images from different grid squares to ensure representative sampling.

- Morphometric Analysis: Measure virion dimensions (diameter for spherical viruses, length/width for filamentous viruses) and characterize surface features (glycoprotein spikes, capsomer arrangement).

Taxonomic Application: Distinguishes enveloped vs. non-enveloped viruses; identifies nucleocapsid symmetry; differentiates viral families based on characteristic morphologies (herpesviruses vs. adenoviruses vs. rhabdoviruses).

Case Study: Structural Taxonomy of Archaeal Viruses

Recent advances in viral taxonomy, particularly for archaeal viruses, demonstrate the powerful integration of structural data with genomic information for classification. In the 2025 ICTV ratification, numerous new archaeal virus taxa were established based on structural characteristics observed through electron microscopy and predicted from genomic data [23].

The order Caudoviricetes was expanded with six new families of head-tailed viruses, maintaining the conserved icosahedral capsid structure connected to a tail, a hallmark of this group [23]. Simultaneously, the order Ligamenvirales received one new family of filamentous viruses (Chiyouviridae) with helical symmetry [23]. Perhaps most significantly, viruses with pleomorphic virions associated with Archaeoglobi were classified into the family Thalassapleoviridae within a completely new phylum (Calorviricota), order (Ageovirales), and class (Caminiviricetes) [23]. This establishment of higher-level taxa based on distinctive virion architecture underscores how structural features drive the recognition of major evolutionary lineages in virology.

Table 3: Recently Classified Archaeal Virus Families (ICTV 2025)

| Virus Family | Host Range | Virion Morphology | Structural Classification | Higher Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apasviridae | Marine Group II Archaea (Poseidoniales) | Head-tailed | Icosahedral capsid with tail [23] | Order Magrovirales, Class Caudoviricetes |

| Thalassapleoviridae | Archaeoglobi | Pleomorphic, enveloped | Enveloped virions, no fixed symmetry [23] | New Phylum: Calorviricota, New Class: Caminiviricetes |

| Chiyouviridae | Bathyarchaeia | Filamentous | Helical symmetry [23] | Order Ligamenvirales, Realm Adnaviria |

| Nipumfusiviridae | Nitrososphaerales | Spindle-shaped | Elongated, lemon-shaped virions [23] | Unassigned to higher taxa |

| Usuviridae | Methanobrevibacter | Head-tailed | Icosahedral capsid with tail [23] | Order Methanobavirales, Class Caudoviricetes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Viral Structural Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function in Research | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holey Carbon Grids | Cryo-EM sample preparation | Support film with holes for spanning vitreous ice | Preservation of native virus structure without staining [21] |

| Uranyl Acetate | Negative stain EM | Heavy metal contrast agent | Rapid morphological assessment and sample screening |

| Sucrose/Cesium Chloride | Virus purification | Density gradient medium | Isolation of intact virions from cell lysates [21] |

| Detergents (Triton X-100, SDS) | Envelope disruption | Lipid membrane solubilization | Differentiation of enveloped vs. non-enveloped viruses [19] |

| Proteinase K | Structural analysis | Protein digestion | Determining protein-protected genomic regions in virions |

| Lipid Raft Disruptors (MβCD) | Envelope function studies | Cholesterol depletion from membranes | Studying envelope fusion and infectivity mechanisms [24] |

Structural characteristics—including capsid symmetry, envelope properties, and overall virion architecture—remain foundational elements in viral taxonomy that complement genomic data. The integration of electron microscopy with bioinformatic analyses enables virologists to establish natural taxonomic groupings that reflect evolutionary relationships and functional adaptations. As demonstrated by the recent classification of diverse archaeal viruses, structural virology continues to reveal unexpected diversity in the virosphere and provides essential criteria for the recognition of novel viral taxa at all hierarchical levels. For researchers in drug development, these structural insights facilitate the rational design of antiviral agents that target essential virion components, from capsid-binding compounds to envelope-disrupting agents.

Electron microscopy (EM) remains an indispensable tool in virology, providing an unbiased "open view" for detecting and identifying viral pathogens without prior knowledge of their genetic sequence. This capability is crucial during the initial phases of outbreaks involving unknown or emerging viruses, where molecular assays do not yet exist [3] [25]. While molecular methods like PCR offer high sensitivity for known pathogens, EM's ability to visualize the entire infectious unit based on morphology alone makes it uniquely valuable for frontline viral detection and research [3]. The technique continues to evolve, integrating with modern technologies to maintain its relevance in contemporary virology and drug development pipelines.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted EM's ongoing importance, with numerous studies employing it to characterize SARS-CoV-2 ultrastructure and morphometric variations across variants [5]. This application note details the methodologies, quantitative findings, and practical protocols that demonstrate EM's critical role in viral morphology research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to implement these approaches in their investigative workflows.

Quantitative Morphometric Analysis of Viral Pathogens

Comparative Morphometry of SARS-CoV-2 Variants

Systematic morphometric analysis reveals subtle but potentially significant structural differences between SARS-CoV-2 variants. The table below summarizes key measurements from a comprehensive study of SARS-CoV-2 variants using conventional thin-section transmission electron microscopy:

Table 1: Morphometric Parameters of SARS-CoV-2 Variants from Thin-Section TEM

| Virus Variant | Maximum Particle Diameter (nm) | Particle Circumference (nm) | Spike Number per Virus Profile | Spike Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Munich929 (Reference) | Data from study [5] | Data from study [5] | Data from study [5] | Reference value |

| Italy-INMI1 (Reference) | Data from study [5] | Data from study [5] | Data from study [5] | Reference value |

| Alpha (B.1.1.7) | Slightly smaller | Data from study [5] | Data from study [5] | Increased |

| Beta (B.1.351) | Larger | Data from study [5] | Reduced | Reduced |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) | Slightly smaller | Data from study [5] | Data from study [5] | Increased |

| Omicron BA.2 | Slightly smaller | Data from study [5] | Data from study [5] | Increased |

This data, collected from approximately 900 TEM images of different SARS-CoV-2 variants, shows that the more dominant variants (Alpha, Delta, Omicron BA.2) exhibited slightly increased spike density compared to reference strains, primarily due to smaller particle size [5]. In contrast, the less dominant Beta variant showed reduced spike density with larger particle size [5]. These findings align with similar tendencies observed in cryo-electron tomography studies, suggesting morphometric parameters may influence viral fitness [5].

Data Utilization in Electron Microscopy Studies

The volume of data generated in EM studies presents both challenges and opportunities for research. Analysis of EM data utilization reveals significant potential for maximizing research outputs:

Table 2: Electron Microscopy Data Generation and Utilization Analysis

| Parameter | Value | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Total EM images analyzed | 152,097 images (403 GB) | Highlights substantial data generation capacity in core facilities |

| Average annual image acquisition | >10,000 images | Demonstrates consistent instrumentation usage across projects |

| Percentage of images published | Approximately 2% (3,577 images) | Indicates substantial "lost data" with research potential |

| Composition of archive | 74% SEM, 23% TEM, 3% STEM | Reflects specialization in surface versus internal structure analysis |

| Potential unused data | >90% | Represents opportunity for data mining and AI development |

This analysis of over 150,000 EM images from a core facility revealed that more than 90% of scientifically significant data remains unpublished, representing both a challenge in data utilization and an opportunity for mining existing datasets for new insights [26]. For virology research, this suggests that existing EM archives may contain valuable unanalyzed structural information about viral pathogens.

Diagnostic Electron Microscopy Methods and Protocols

Negative Staining EM for Suspension Samples

Negative staining transmission electron microscopy provides a rapid method for visualizing viral particles in suspensions from various sample types, including cell culture supernatants, respiratory secretions, or purified viral preparations [3].

Protocol: Negative Staining for Viral Detection

Sample Preparation:

- Grid Preparation: Use 300-400 mesh copper grids filmed with Formvar or Pioloform. Apply a thin carbon layer to enhance stability during imaging.

- Surface Treatment: Render the grid surface hydrophilic using either glow discharge plasma treatment or chemical conditioning with 0.1-0.5% Alcian blue for 10 minutes [3].

- Particle Adsorption:

- For dense particles (e.g., bacteria, poxviruses): Use Drop-On-Grid (DOG) method - apply 5-10 µL of sample suspension directly to grid surface for 1 minute [3].

- For less dense particles or samples with high background: Use Grid-On-Drop (GOD) method - float grid on 20-30 µL droplet of sample for 1-5 minutes [3].

- Washing: Rinse grid gently with 5-10 drops of distilled water or ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.0) to remove salts and soluble contaminants.

- Staining: Apply 5-10 µL of 1-2% uranyl acetate (or 1-2% phosphotungstic acid neutralized to pH 6.5-7.0) for 10-30 seconds. Blot excess stain with filter paper [3].

- Drying: Air-dry grid completely before EM examination.

Imaging and Analysis:

- Examine grids at 20,000-50,000× magnification using TEM.

- Systematically scan grid squares at lower magnification to identify representative areas.

- Capture images of potential viral particles at higher magnification for morphometric analysis.

- Identify viruses based on characteristic morphological features: size, shape, surface structures, and assembly patterns [3].

Figure 1: Negative Staining Workflow for Viral Detection. This protocol provides rapid preparation of suspension samples for TEM visualization of viral particles.

Thin-Section EM for Infected Cells and Tissues

Conventional thin-section EM allows visualization of viral particles in the context of infected cells and tissues, providing information about replication sites, morphogenesis, and virus-host interactions [5] [3].

Protocol: Thin-Section EM for Virus-Cell Interaction Studies

Sample Preparation and Processing:

- Cell Culture Infection: Infect Vero E6 cells (or other permissive cells) with virus at MOI 0.01-1.0. Incubate for 24 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [5].

- Fixation: Replace medium with primary fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.2). For better membrane preservation, use combination fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde + 1% paraformaldehyde in HEPES buffer). Fix for at least 1 hour at room temperature [5].

- Cell Harvesting: Scrape fixed cells from culture flasks and collect by centrifugation (3000 g for 10 minutes) [5].

- Embedding: Mix cell pellet with 3% low-melting point agarose (1:1 v/v) at 40°C. Centrifuge briefly to concentrate cells [5].

- Post-fixation and Staining: Treat with 1% osmium tetroxide in buffer for 1 hour, followed by en bloc staining with 0.5% uranyl acetate for 30 minutes [3].

- Dehydration: Process through graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%) or acetone.

- Infiltration and Embedding: Infiltrate with epoxy resin (Epon, Spurr's) or LR White, then polymerize at appropriate temperature.

- Sectioning: Cut ultrathin sections (60-90 nm) using ultramicrotome, collect on EM grids.

- Section Staining: Stain with uranyl acetate and lead citrate for contrast enhancement.

Imaging and Morphometric Analysis:

- Acquire images at 10,000-40,000× magnification.

- For morphometric analysis, measure maximum particle diameter, circumference, and count spike proteins using appropriate software [5].

- Compare with reference datasets for variant identification and characterization.

Figure 2: Thin-Section EM Workflow for Viral Morphogenesis Studies. This protocol preserves architectural context of viral infection in host cells.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Viral EM

Successful electron microscopy of viral pathogens requires specific reagents and materials optimized for preserving and contrasting delicate viral structures. The following table details essential solutions for viral EM workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Electron Microscopy

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in Viral EM | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Fixative | 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) | Crosslinks and stabilizes viral and cellular structures | For thin-section EM; may include 1% paraformaldehyde for enhanced preservation [5] |

| Negative Stain | 1-2% uranyl acetate or 1-2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 6.5-7.0) | Creates negative contrast around viral particles | Uranyl acetate provides finer grain; neutral pH maintains structure [3] |

| Secondary Fixative | 1% osmium tetroxide in buffer | Stabilizes lipids and adds electron density | Essential for membrane preservation in thin sections [3] |

| Embedding Resin | Epon, Spurr's, or LR White epoxy resins | Provides structural support for ultrathin sectioning | Different resins offer varying hardness and sectioning properties |

| Section Stains | Uranyl acetate (0.5-2%) and lead citrate | Enhances contrast of cellular and viral components | Sequential application with thorough washing between [3] |

| Grid Support Films | Formvar or Pioloform with carbon coating | Provides electron-transparent support for samples | 300-400 mesh copper grids most common [3] |

| Surface Conditioner | 0.1-0.5% Alcian blue or glow discharge | Creates hydrophilic surface for sample adhesion | Alcian blue provides consistent particle adsorption [3] |

Application in Emerging Viral Disease Investigation

EM's open view capability makes it particularly valuable for initial identification of unknown viral pathogens during outbreak investigations. The approach has demonstrated effectiveness across multiple viral families:

Outbreak Investigation Protocol:

- Rapid Sample Triage: Apply negative staining EM to various sample types (respiratory secretions, tissue homogenates, cell culture supernatants) within hours of receipt [3].

- Morphological Categorization: Classify observed particles into major viral families based on size, shape, and structural characteristics:

- Contextual Analysis: For tissue samples, use thin-section EM to visualize viral particles in pathological context, identifying replication sites and cytopathic effects.

- Correlation: Combine EM findings with clinical presentation and epidemiology to prioritize further characterization using molecular methods.

This approach was instrumental during the early COVID-19 pandemic, where EM provided among the first images of SARS-CoV-2 and confirmed its classification as a coronavirus [5]. Similarly, EM has historically played crucial roles in identifying novel viruses during outbreaks of Ebola, SARS, and other emerging infections [25].

For drug development professionals, EM provides critical insights into virus-cell interactions that can inform therapeutic targets and assess antiviral mechanisms. The ability to directly visualize viral entry, assembly, and egress, as well as morphological changes induced by antiviral compounds, makes EM an invaluable tool throughout the drug development pipeline.

Future Directions and Advanced Methodologies

The field of diagnostic EM continues to evolve with technological advancements. Volume Electron Microscopy (vEM) techniques, including Serial Block-Face SEM (SBF-SEM), Focused Ion Beam SEM (FIB-SEM), and array tomography, now enable comprehensive 3D ultrastructural analysis of virus-infected cells and tissues [27]. These methods provide unprecedented views of viral replication cycles in their native cellular context.

Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy (CLEM) combines the dynamic capabilities of live-cell imaging with the high resolution of EM, allowing researchers to track specific viral components and events over time before examining their ultrastructural details [28] [29]. This approach is particularly powerful for studying the dynamics of viral entry and assembly.

Computational advances, including machine learning and automated image analysis pipelines, are addressing the challenge of data volume and complexity in viral EM [26] [29]. These tools enable rapid detection and classification of viral particles in complex samples, potentially increasing throughput and standardization of diagnostic EM.

While cryo-electron microscopy and cryo-electron tomography offer exceptional structural preservation for high-resolution studies of viral architecture [5], conventional EM methods remain more accessible and practical for routine diagnostic applications and rapid response to emerging threats [3]. The integration of these advanced methodologies with established EM protocols ensures that electron microscopy will maintain its essential role in viral detection and characterization for foreseeable future.

The field of structural virology has undergone a profound transformation, driven by the evolution of electron microscopy (EM) from a purely descriptive tool into a powerful platform for quantitative analysis. Due to their small size, viruses can only be clearly visualized by electron microscopy, making EM an indispensable technology for understanding viral replication and pathogenesis [30]. Early EM techniques provided the first glimpses of viral morphology, enabling the classification of viruses based on their physical structure. However, these traditional approaches were largely qualitative, limited to illustrating what viruses look like. The contemporary revolution in EM technologies has shifted this paradigm dramatically. Today, advanced EM methods facilitate precise three-dimensional structural determination, quantification of viral components within individual particles, and statistical analysis of structural heterogeneity across viral populations [31] [30]. This evolution has positioned EM as a cornerstone technology in virology, with critical applications in understanding viral life cycles, pathogenesis, and the development of antiviral therapeutics.

The journey from descriptive visualization to quantitative analysis represents a fundamental shift in how researchers investigate virus-cell interactions. Where conventional thin-section transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of plastic-embedded material revealed the basic architecture of viral assemblies, modern techniques like electron tomography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and volume electron microscopy (vEM) now enable researchers to quantify viral budding efficiencies, statistically analyze maturation states, and map the spatial distribution of viral components with nanometer precision [30] [27]. This application note details this technological evolution, providing structured protocols, analytical frameworks, and practical resources to harness the full quantitative potential of EM in viral research.

The Evolution of EM Techniques in Virology

From Qualitative Morphology to Quantitative Ultrastructure

The application of electron microscopy in virology has progressed through distinct technological phases, each expanding the quantitative capabilities available to researchers. The following table summarizes the key evolutionary stages and their impact on viral research:

Table 1: Evolutionary Stages of EM in Virology

| Technological Era | Key Methodologies | Primary Applications in Virology | Quantitative Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Morphology | Thin-section TEM, Negative staining [30] [32] | Viral classification, Basic morphogenesis studies, Diagnostic identification | Dimensional measurements, Qualitative assessment of assembly stages |

| Immuno-EM | Immunolabeling of cryosections [30] | Subcellular localization of viral components, Trafficking pathways | Semi-quantitative localization frequency, Relative abundance of antigens |

| 3D Reconstruction | Electron tomography, Single-particle analysis [30] | Viral architecture, Conformational states | 3D spatial measurements, Resolution to sub-nanometer level |

| Quantitative Volume EM | Serial block-face SEM, FIB-SEM, Array tomography [27] | Host-pathogen interactions, Viral factories, Organelle remodeling | Spatial statistics, Volume renderings, Population heterogeneity analysis |

| Cryo-EM/ET | Cryo-electron microscopy, Cryo-electron tomography [31] | Native structure determination, Structural dynamics | Atomic-scale resolution, Structural ensemble analysis |

This progression has fundamentally transformed how virologists approach structural questions. While negative staining EM—which uses heavy metal salts to enhance contrast between the background and the virion's image—remains a valuable rapid technique for initial morphological assessment [32], the field has increasingly moved toward methods that preserve native structures and enable statistical analysis. Techniques like immunolabeling of cryosections allow not only the localization but also the quantification of viral components, even in individual virus particles, enabling comparisons between particles at different cellular locations or assembly stages [30]. Meanwhile, the development of volume electron microscopy (vEM), encompassing techniques including Serial Block Face SEM (SBF-SEM), Focused Ion Beam SEM (FIB-SEM), and array tomography, has opened new possibilities for capturing subcellular architecture across cells, tissues, and entire small model organisms [27].

Workflow: From Sample to Quantitative Insight

The modern quantitative EM workflow for structural virology integrates multiple specialized steps, each contributing to the reliability and statistical power of the final analysis:

Diagram 1: Quantitative EM Workflow for Virology

This integrated workflow highlights the critical pathway from biological specimen to quantitative insight. For enveloped viruses specifically, preservation of membrane structures is essential, achieved through specialized protocols such as post-fixation in reduced osmium (1% osmium tetroxide in 1.5% potassium ferricyanide) and treatment with tannic acid to enhance membrane contrast [30]. The computational analysis phase has become increasingly sophisticated, with tools like cryoDRGN using machine learning approaches to reconstruct heterogeneous ensembles of cryo-EM density maps, and emClarity providing GPU-accelerated processing for subtomogram averaging and classification at high resolution [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Epon Embedding for Ultrastructural Analysis of Viral Assembly

This protocol details the preparation of virus-infected cells for traditional transmission electron microscopy, enabling the qualitative assessment and quantitative analysis of viral morphogenesis and host-cell modifications [30].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Epon Embedding

| Reagent/Chemical | Specification/Purity | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Paraformaldehyde | Electron microscopy grade, 16% solution | Primary fixative: rapidly penetrates cells to stabilize proteins |

| Glutaraldehyde | EM grade, 25% aqueous solution | Cross-linking fixative: preserves ultrastructure and membranes |

| Phosphate Buffer | 0.2 M, pH 7.4 | Physiological buffer for fixation maintains cellular integrity |

| Osmium Tetroxide | Crystalline, 4% aqueous solution | Post-fixation: stabilizes and stains lipid membranes |

| Potassium Ferricyanide | ACS reagent grade, ≥99.0% | Reducing agent with OsO4 enhances membrane contrast |

| Tannic Acid | Low molecular weight (Gallotannin) | Mordant: improves contrast of membranes and fine structures |

| Sodium Cacodylate | 0.2 M, pH 7.4 | Buffer for post-fixation steps maintains tissue integrity |

| Ethanol Series | 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100% | Dehydration: gradual water removal for resin infiltration |

| Propylene Oxide | Electron microscopy grade | Transition solvent: facilitates resin infiltration |

| Epon 812 Epoxy Resin | EM embedding kit | Infiltration and embedding: provides stable support for sectioning |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Primary Fixation: Prepare double-strength fixative (4% formaldehyde, 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). Add an equal volume of this fixative directly to the culture medium of virus-infected cells. Fix for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Note: For pathogenic viruses, this step inactivates pathogens for safe handling. [30]

Post-fixation and Membrane Contrast: Wash cells 3x with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. Incubate cells with 1% osmium tetroxide in 1.5% potassium ferricyanide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 1 hour on ice. This step is critical for preserving the membrane structures of enveloped viruses. [30]

Tannic Acid Treatment: Wash cells and incubate with 1% tannic acid in 0.05 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 45 minutes at room temperature. Follow with a brief rinse in 1% sodium sulfate for 5-10 minutes. This step acts as a mordant, dramatically improving the contrast and delineation of viral and cellular membranes. [30]

Dehydration: Perform graded ethanol dehydration: 30%, 50%, 70%, 90% (10 minutes each), followed by 3 changes of 100% ethanol (15 minutes each).

Resin Infiltration and Embedding: Infiltrate with Epon 812 resin using a progressive series of resin:ethanol mixtures (1:2, 1:1, 2:1) for 1-2 hours each, followed by pure resin overnight. Transfer to fresh resin in embedding molds and polymerize at 60°C for 48 hours.

Sectioning and Staining: Cut ultrathin sections (60-80 nm) using an ultramicrotome. Collect sections on EM grids. Contrast with lead citrate for 1-2 minutes before viewing in the TEM.

Applications in Virology

This protocol is particularly valuable for studying the assembly of complex viruses such as the beta-herpesvirus human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and primate lentiviruses (SIV and HIV) [30]. It enables researchers to identify morphological features of various assembly stages, distinguish immature and mature particles, and analyze the acquisition of lipid membranes by enveloped viruses through budding processes.

Protocol 2: Negative Staining for Rapid Visualization of Viral Particles

This straightforward technique provides a rapid method for initial morphological assessment of viral preparations, using heavy metal salts to create a negative impression of viral particles [32].

Materials

- Formvar-coated EM grids

- Virus preparation (pelleted and resuspended in distilled water)

- Phosphotungstic acid (PTA), 2.0%, pH 7.0

- Filter paper

Procedure

- Place a drop of purified viral suspension on a clean petri dish.

- Carefully place a Formvar-coated EM grid (Formvar side down) on top of the virus drop for 1-3 minutes.

- Remove the grid and gently blot excess liquid with filter paper.

- Place the grid onto a drop of 2.0% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.0) for one minute.

- Remove excess PTA by blotting and allow the grid to air dry completely before EM examination. [32]

Protocol 3: Immunogold Labeling for Quantification of Viral Components

This protocol enables the quantitative localization of specific viral antigens within infected cells and even within individual virions, providing statistical data on component distribution.

Materials

- Ultrathin cryosections of virus-infected cells (approximately 50-80 nm)

- Primary antibodies against viral antigens

- Protein A-gold or secondary antibody-gold conjugates (5-15 nm gold particles)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with glycine

- PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)

- Methyl cellulose/uranyl acetate solution

Procedure

- Collect ultrathin cryosections on EM grids coated with Formvar and carbon.

- Float grids on drops of PBS/glycine to quench free aldehyde groups.

- Incubate on drops of PBS/BSA to block non-specific binding.

- Incubate with primary antibody against viral antigen (diluted in PBS/BSA) for 30-60 minutes.

- Wash thoroughly with PBS/BSA.

- Incubate with Protein A-gold or immunogold conjugate for 20-30 minutes.

- Wash with PBS followed by distilled water.

- Contrast with uranyl acetate and embed in methyl cellulose/uranyl acetate.

- After drying, examine in TEM and quantify gold particle distribution per viral particle or cellular compartment. [30]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of quantitative EM in virology requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions for researchers in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Viral EM

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Viral EM Research |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation Systems | 4% Formaldehyde/3% Glutaraldehyde blend, High-pressure freezing apparatus | Structural preservation of viral assemblies and host-cell ultrastructure |

| Contrast Enhancement | Osmium tetroxide/Potassium ferricyanide, Tannic acid, Uranyl acetate | Membrane stabilization and electron density for high-contrast imaging |

| Embedding Media | Epon 812, Lowicryl resins, LR White | Tissue support for ultrathin sectioning; antigen preservation for immuno-EM |

| Immunolabeling Reagents | Protein A-gold conjugates, Immunogold probes (5-15 nm) | Antigen localization and quantification within viral particles and cellular compartments |

| Cryo-EM Reagents | Quantifoil grids, Liquid ethane, Cryo-protectants | Vitrification for native-state structural analysis of virions |

| Software Solutions | CryoDRGN, emClarity, IMOD, SerialEM | Image processing, tomographic reconstruction, heterogeneity analysis, and segmentation |

| Volume EM Consumables | Diamond knives, GridTape, Conductive tape | Automated serial sectioning for large-volume vEM datasets |

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Quantitative Analysis of Viral Morphogenesis

The transition to quantitative EM requires robust analytical frameworks for interpreting the rich datasets generated by modern instrumentation. For viral morphogenesis studies, this typically involves:

Morphometric Analysis of Assembly Intermediates: Precise measurement of viral particle dimensions, capsid thickness, and core condensation states across a population enables statistical classification of assembly intermediates. This is particularly valuable for distinguishing immature, intermediate, and mature forms of viruses like HIV, where maturation involves profound structural reorganization. [30]

Spatial Distribution Analysis: Quantitative mapping of viral particles and components within cellular compartments provides insights into replication strategies. This can include statistical analysis of preferential budding sites, association with specific organelles, or clustering patterns within viral factories.

Immunogold Quantification: Statistical analysis of gold particle distributions per viral particle or unit area of cellular compartment enables precise quantification of viral component localization, even revealing differential composition of particles at different cellular locations or assembly stages. [30]

Structural Heterogeneity Analysis

Advanced computational methods now enable the analysis of structural heterogeneity within viral populations, moving beyond single, static structures to understanding dynamic conformational ensembles:

Diagram 2: Viral Structural Heterogeneity Analysis

Machine learning approaches like cryoDRGN (Deep Reconstruction of Generative Networks) are particularly powerful for analyzing structural heterogeneity in viral complexes, reconstructing diverse ensembles of cryo-EM density maps from single-particle datasets [31]. This capability is crucial for understanding functional mechanisms in flexible viral glycoproteins, pleomorphic virions, or assembly intermediates that exist in multiple conformational states.

Application Notes: Case Studies in Viral Research

Case Study 1: Quantitative Analysis of HIV Morphogenesis

The application of quantitative EM to HIV research has revealed intricate details of the viral assembly and maturation process. Through careful morphometric analysis of plastic sections and immunogold labeling, researchers have quantified the distribution of viral components between immature and mature particles, the kinetics of Gag processing, and the spatial relationship between viral budding sites and cellular compartments. [30]

Key Quantitative Findings:

- Statistical analysis of capsid condensation states reveals intermediate maturation forms

- Gold particle quantification demonstrates differential incorporation of viral envelope glycoproteins

- Spatial analysis shows preferential budding at specific microdomains of the plasma membrane

Case Study 2: Volume EM of Viral Factories in Cytomegalovirus Infection

HCMV infection induces profound reorganization of cellular architecture, including the formation of elaborate viral assembly compartments. Volume EM approaches enable the quantitative three-dimensional analysis of these virus-induced structures, providing insights into their organization and functional significance. [30] [27]

Quantitative Volume Analysis:

- Segmentation and volumetric measurement of viral assembly compartments

- Spatial statistics of particle distribution within infected cells

- Membrane surface area calculations for organelle remodeling

The integration of these quantitative EM approaches continues to transform our understanding of viral replication strategies, host-pathogen interactions, and the structural basis of antiviral interventions. As EM technologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput, automation, and integration with complementary modalities, the capacity for quantitative analysis in structural virology will expand further, enabling increasingly sophisticated investigations into the nanoscale world of viruses.

From Sample to Structure: Methodological Workflows and Cutting-Edge Applications in Virology

In the field of viral morphology research, the quality of electron microscopy (EM) data is fundamentally determined by specimen preparation. The choice between chemical fixation and cryo-preservation represents a critical methodological crossroads, each pathway preserving cellular and viral ultrastructure through fundamentally different physical principles. Chemical fixation employs cross-linking agents to stabilize biomolecules, while cryo-preservation rapidly vitrifies water to arrest biological processes in a near-native state. For researchers investigating viral pathogenesis, replication organelle formation, and virus-host interactions, the selection of an appropriate preparation strategy directly influences the resolution and biological relevance of the resulting structural data. This application note provides detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for these cornerstone techniques, contextualized within the specific requirements of contemporary virology research.

Table 1: Core Specimen Preparation Methods in Viral Research

| Method | Primary Principle | Key Applications in Virology | Spatial Resolution | Key Artifacts/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Fixation | Aldehyde cross-linking of proteins; osmium tetroxide stabilization of lipids | Study of viral assembly sites, virus-induced membrane remodeling, and infected cell pathology [30] [33] | ~2-5 nm (plastic sections) | Membrane distortion, protein extraction, antigen masking [3] [33] |

| Cryo-Preservation (Vitrification) | Ultra-rapid cooling to form non-crystalline (vitreous) ice | Visualization of viral particles and replication complexes in near-native state; single-particle analysis [34] [35] | <3 Å (for high-resolution SPA) | Sample thickness limitations, beam-induced motion, requiring specialized equipment [34] [3] |

| Negative Staining | Heavy metal salt embedding of surface structures | Rapid diagnostic imaging of viral particles in suspensions, antibody binding studies (IEM) [3] [36] | ~1-2 nm | Stain penetration artifacts, flattening of particles, not suitable for internal structure [3] |

Chemical Fixation: Protocols for Structural Preservation in Viral Research

Chemical fixation remains a widely accessible and robust method for preserving viral-infected cells and tissues. The goal is to rapidly stabilize biological structures against the subsequent stresses of dehydration, embedding, and sectioning, while minimizing artifactual changes to the native state.

Standard Aldehyde-Osmium Protocol for Plastic Embedding

This protocol is optimized for preserving the membrane structures critical for studying enveloped viruses and viral replication organelles [30] [37].

Materials:

- Primary Fixative: 2% formaldehyde (from paraformaldehyde) + 1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4

- Post-fixative: 1% osmium tetroxide in 1.5% potassium ferricyanide

- Contrasting Agent: 1% tannic acid in 0.05 M sodium cacodylate buffer

- Dehydration Series: Ethanol or acetone (50%, 70%, 90%, 100%)

- Embedding Resin: Epon 812 or equivalent epoxy resin

Methodology:

- Primary Fixation: Prepare a double-strength fixative (4% formaldehyde/3% glutaraldehyde) and add it directly to the culture medium containing infected cells at a 1:1 ratio. Fix for at least 1 hour at room temperature. For tissue samples, perfuse or immerse small (<1 mm³) pieces in fixative [30].

- Washing: Rinse cells/tissue three times with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (5 minutes each) to remove excess aldehydes.

- Post-fixation: Incubate with 1% osmium tetroxide in 1.5% potassium ferricyanide for 1 hour on ice. This step specifically stabilizes lipid membranes, which is crucial for visualizing viral envelopes and modified intracellular membranes [30].

- Tannic Acid Treatment: Wash samples and incubate in 1% tannic acid in 0.05 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 45 minutes at room temperature. This acts as a mordant, enhancing membrane contrast and fine delineation of cellular structures [30].

- Dehydration: Process through a graded ethanol series (50%, 70%, 90%, 100%) with 10-15 minutes per step, followed by a second change of 100% ethanol.

- Embedding: Infiltrate with epoxy resin (e.g., Epon 812) using a progressive resin:ethanol ratio (e.g., 1:2, 1:1, 2:1), followed by pure resin changes. Polymerize at 60°C for 48 hours [30] [37].

- Sectioning: Cut ultrathin sections (60-80 nm thickness) using an ultramicrotome with a diamond knife. Collect sections on naked copper grids.

- Staining: Contrast sections with uranyl acetate (saturated solution in 50% ethanol, 10-20 minutes) followed by lead citrate (2-5 minutes) [37].

Rapid Embedding Protocol for Clinical Specimens

For time-sensitive diagnostic applications or processing small-volume samples (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs), a rapid protocol can be employed [37].

Materials:

- Primary Fixative: 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 M HEPES buffer, pH 7.2

- Post-fixative: 1% osmium tetroxide in water

- Embedding Resin: LR White acrylic resin

Methodology:

- Sample Concentration: For swab suspensions or low-titer virus preparations, concentrate particles by desktop ultracentrifugation (e.g., Airfuge) at approximately 120,000×g for 10 minutes [37].

- Primary Fixation: Mix sample with equal volume of primary fixative for 30-60 minutes.

- Pellet Handling: Embed the resulting tiny pellet in low-melting point agarose (3%) to prevent dispersal during processing.

- Post-fixation: Treat with 1% osmium tetroxide for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Dehydration and Embedding: Rapid dehydration through ethanol series and embed in LR White resin. Polymerize at 50°C for 24 hours or using chemical accelerators [37].

Diagram 1: Chemical fixation and embedding workflow for viral samples (6 characters)

Cryo-Preservation: Advanced Techniques for Near-Native State Analysis