Viral Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT): Protocols, Applications, and Advances in Molecular Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of viral Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Viral Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT): Protocols, Applications, and Advances in Molecular Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of viral Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of NAT, including its critical role in shortening the diagnostic window period for viruses like HIV, HBV, and HCV. The scope extends to detailed methodological approaches such as qRT-PCR, isothermal amplification, and high-throughput sequencing, with applications in clinical diagnostics, blood safety, and vaccine development. The content also addresses common challenges, optimization strategies for sensitivity and specificity, and a comparative analysis of commercial platforms and regulatory standards. This resource synthesizes current knowledge and future directions to guide research and implementation in biomedical science.

The Principles and Significance of Viral Nucleic Acid Testing

Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) represents a group of techniques used to detect a specific nucleic acid sequence, thereby identifying a particular species or subspecies of an organism, most commonly viruses or bacteria that act as pathogens in clinical samples such as blood, tissue, or urine [1]. The fundamental principle that distinguishes NATs from other diagnostic methods (like antigen or antibody tests) is their direct targeting of genetic material—either DNA or RNA [1]. This approach allows for the early diagnosis of infectious diseases because it does not rely on the host's immune response; the detection of antigens or antibodies requires time for them to appear in the bloodstream in detectable quantities [1].

The core of virtually all nucleic acid detection technologies is the specificity of Watson-Crick base pairing, where single-stranded probe molecules are designed to bind exclusively to complementary DNA or RNA target sequences [1]. Since the amount of a specific genetic material in a sample is often minimal, many NATs incorporate an amplification step, classifying them as Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs) [1]. Prominent examples of amplification methods include the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), transcription-mediated assay (TMA), and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [1].

Core Principles and Methodologies

The effectiveness of NAT hinges on several foundational principles and a workflow that ensures specificity and sensitivity.

The Principle of Hybridization and Probe Design

The process of nucleic acid strands with complementary sequences binding together is called hybridization [1]. However, achieving perfect specificity, especially to distinguish between sequences that differ by only a single base (as in Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms, or SNPs), is a critical challenge. Imperfect probe-target binding can lead to false-positive results [1]. Research has led to advanced probe designs, such as the toehold exchange probe, which consists of a longer complement strand pre-hybridized to a shorter protector strand [1]. When the correct target sequence is present, it binds to the exposed "toehold" region and displaces the protector strand, forming a stable product. Reactions with spurious targets are thermodynamically less favorable, providing high discrimination factors that can range from 3 to over 100, enabling robust detection even in the presence of single-base changes [1].

General Workflow for Viral Pathogen Detection

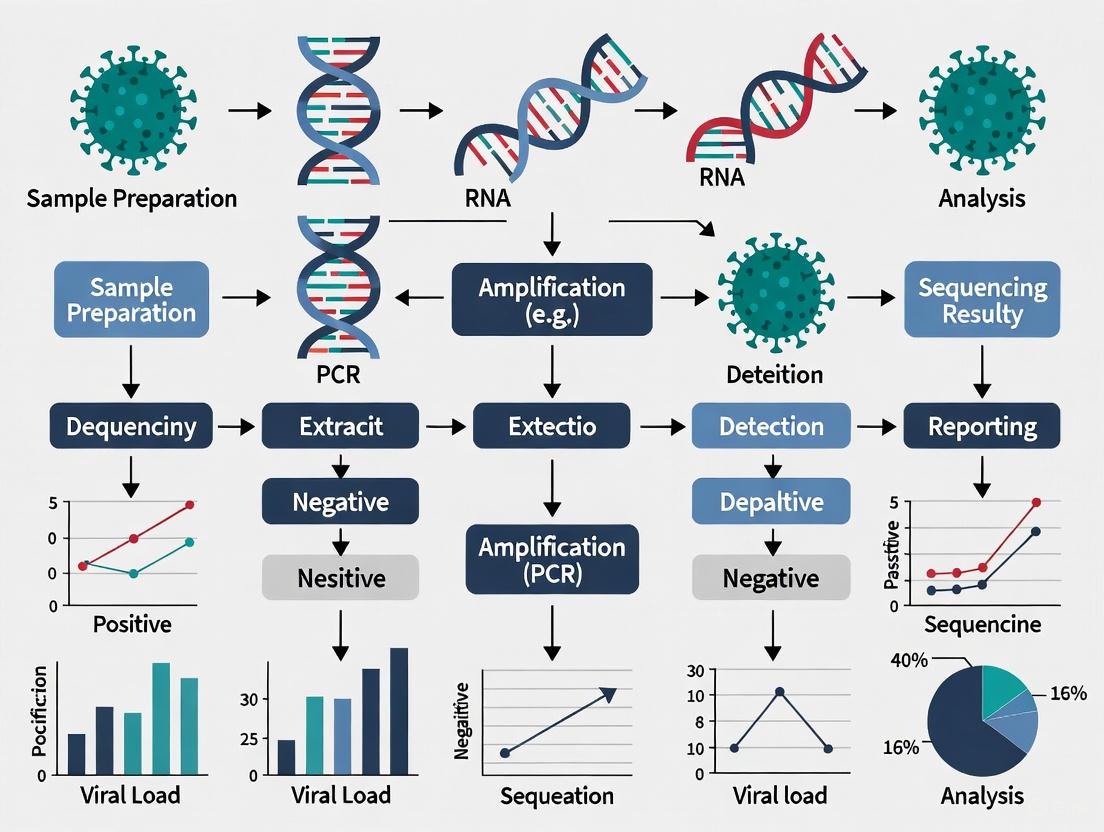

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for detecting a viral pathogen using nucleic acid testing, from sample collection to result interpretation.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of a NAT protocol depends on a suite of critical reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components and their functions.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Nucleic Acid Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Specific Primers & Probes | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences designed to be complementary to and hybridize with a unique target sequence in the pathogen's genome, providing the test's specificity [1]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase (RT) | An enzyme used in tests for RNA viruses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2). It transcribes RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), which can then be amplified by PCR [2]. |

| DNA/RNA Polymerase | A thermostable enzyme that synthesizes new strands of DNA by adding nucleotides to the primer, enabling the exponential amplification of the target sequence during PCR or isothermal amplification [1] [2]. |

| Nucleotides (dNTPs) | The fundamental building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) used by the polymerase enzyme to build new DNA strands [2]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Provide the optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength, co-factors like Mg²⁺) for the enzymatic reactions to proceed efficiently and with high fidelity [2]. |

| Sample Lysis Buffer | A chemical solution used to break open (lyse) cells or viral particles in the collected sample, releasing the nucleic acids for extraction and purification [1]. |

Application Note: SARS-CoV-2 Detection Paradigm

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a catalyst for the advancement and large-scale application of NAT, providing a clear case study of its utility.

The Gold Standard and Its Limitations

For SARS-CoV-2, the Real-Time Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (rRT-PCR or RT-PCR) was established as the gold-standard NAAT [3]. Despite its high sensitivity and specificity, its reliance on specialized laboratory equipment, skilled personnel, and the potential for long turnaround times (up to 72 hours) highlighted critical logistical challenges during a rapidly evolving pandemic [3].

Next-Generation NAT Platforms

In response to these limitations, significant research efforts were directed toward developing faster, more affordable, and user-friendly platforms. Key innovations include [3]:

- CRISPR-Cas Systems: These platforms combine the sensitivity of amplification with the programmability and specificity of CRISPR-Cas enzymes. When integrated with isothermal amplification methods like Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA), they allow for rapid, visual detection of viral RNA.

- Isothermal Amplification Techniques: Methods such as LAMP and RPA amplify nucleic acids at a constant temperature, eliminating the need for expensive thermal cyclers and making them more suitable for point-of-care settings.

- Portable Biosensors: These devices aim to integrate sample processing, amplification, and detection into a miniaturized, portable format for use in field or community settings.

Algorithmic Comparison of Testing Strategies

Public health organizations recommended various strategies for deploying NAATs alongside rapid antigen tests. A quantitative simulation model compared the outcomes of six different testing algorithms in a population of 100,000 individuals, revealing key trade-offs between missed cases, false positives, and test volumes [4] [5].

Table 2: Simulated Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 Testing Algorithms at 10% Prevalence

| Testing Algorithm | Missed Cases (Median) | False-Positive Diagnoses (Median) | Total NAATs Required* |

|---|---|---|---|

| A) NAAT Only | 0 | 0 | 100,000 |

| B) Antigen (Ag) Only | 2,830 | 635 | 0 |

| C) NAAT for Sx/Ag-neg & Asx/Ag-pos | 1,409 | 13 | 33,200 |

| D) NAAT Confirmation of All Ag-neg | 0 | 635 | 92,200 |

| E) Repeat Ag for Ag-neg | 2,280 | 635 | 0 |

| F) NAAT for Asx & Sx/Ag-pos | 1,389 | 13 | 66,700 |

*In addition to 100,000 antigen tests for algorithms B, C, D, and E. Sx: Symptomatic; Asx: Asymptomatic; Ag-neg: Antigen Negative; Ag-pos: Antigen Positive. Data adapted from [4] [5].

The analysis concluded that no single algorithm is optimal for all settings. The choice depends on programmatic priorities: maximizing case detection (Algorithm A or D), conserving NAAT resources (Algorithm B or E), or seeking an efficient balance (Algorithm C) [4] [5]. Algorithm C, which uses NAATs to confirm results that are discordant with symptom status (e.g., a symptomatic person with a negative antigen test), was found to be the most efficient, requiring 25 NAATs to detect one additional case compared to using antigen tests alone [5].

Detailed Protocol: Detection of Viral RNA via RT-PCR

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for detecting the presence of viral RNA from a nasopharyngeal swab sample using RT-PCR, the gold-standard technique for pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 [3] [2].

Principle

The protocol involves the reverse transcription of viral RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA), followed by the polymerase chain reaction amplification of a specific target sequence within the cDNA. The amplification is monitored in "real-time" using fluorescently labeled probes, allowing for both detection and quantification of the viral load [2].

Specimen Collection and Handling

- Collection: Using a sterile synthetic swab (e.g., polyester), collect a sample from the nasopharynx. Place the swab immediately into a tube containing 2-3 mL of viral transport media [3].

- Storage: Store samples at 2-8°C and process within 72 hours. For longer storage, keep at -70°C or below to preserve RNA integrity.

- Safety: Handle all samples as potentially infectious under appropriate biosafety level (BSL-2 or higher) conditions.

Procedure

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Using a commercial RNA extraction kit, purify the viral RNA from 200 µL of the transport media. This typically involves a combination of lysis, binding to a silica membrane, washing, and elution into 50-100 µL of nuclease-free water. This step removes inhibitors that could affect the downstream reaction.

Master Mix Preparation: In a dedicated, clean area, prepare the RT-PCR reaction mix on ice. The following table details the components for a single 20 µL reaction.

Table 3: RT-PCR Reaction Master Mix

Component Final Concentration/Amount Function 2X RT-PCR Reaction Mix 10 µL Contains buffer, dNTPs, and Mg²⁺ Forward Primer (e.g., N gene) 0.5 µM Binds to one strand of the target Reverse Primer (e.g., N gene) 0.5 µM Binds to the complementary strand TaqMan Probe (FAM-labeled) 0.2 µM Fluorescent probe for detection Reverse Transcriptase 0.5 µL Converts RNA to cDNA Hot-Start DNA Polymerase 0.5 U Amplifies cDNA Nuclease-Free Water To 18 µL Solvent Template RNA 2 µL The extracted sample RNA - Plate Setup: Pipette 18 µL of the master mix into each well of a 96-well PCR plate. Add 2 µL of the extracted RNA sample to the respective wells. Include positive controls (synthetic viral RNA) and negative controls (nuclease-free water) in each run. Seal the plate with an optical adhesive cover.

RT-PCR Amplification: Place the plate in a real-time PCR instrument and run the following program.

Table 4: Thermal Cycling Conditions

Step Temperature Time Cycles Purpose Reverse Transcription 50°C 15-30 minutes 1 Synthesis of cDNA from RNA Initial Denaturation 95°C 2-5 minutes 1 Activates polymerase, denatures cDNA Amplification 95°C 15-30 seconds 40-45 Denaturation 55-60°C 30-60 seconds Primer annealing & extensionFluorescence data collection

Data Analysis

- Cycle Threshold (Ct): The primary output is the Ct value, which is the number of cycles required for the fluorescence signal to cross a predetermined threshold.

- Interpretation: A sample is generally considered positive if it produces exponential amplification with a Ct value below a validated cut-off (e.g., Ct < 40). The negative control must show no amplification, and the positive control must amplify with an expected Ct value for the run to be considered valid.

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

The field of nucleic acid detection continues to evolve, driven by the need for greater speed, simplicity, and accessibility.

Isothermal Amplification and Blocker Displacement Amplification (BDA)

Isothermal techniques, such as Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), provide an alternative to PCR by operating at a single temperature, facilitating point-of-care use [1]. Furthermore, advanced methods like Blocker Displacement Amplification (BDA) have been developed to address the challenge of detecting rare DNA variants [1]. BDA is a modified PCR method that can selectively amplify sequence variants present at very low frequencies (≤ 0.1% allele frequency) by 1000-fold over wildtype sequences. This technique is particularly robust across a range of annealing temperatures (56°C to 64°C), making it suitable for multiplexed enrichment of various genomic variants and for use with portable thermocyclers [1].

Biosafety and Synthesis Screening

As nucleic acid technologies advance, including the ability to synthesize nucleic acids de novo, regulatory frameworks are adapting to address biosecurity concerns. A key development is the forthcoming Framework for Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening, which will require, as a federal funding condition, that purchases of synthetic nucleic acids or synthesis equipment be made only from providers that screen orders for sequences of concern to prevent potential misuse [6]. This highlights the growing importance of security considerations in nucleic acid research.

Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing (NAT) has revolutionized blood safety by dramatically reducing the diagnostic window period for major transfusion-transmitted viruses (TTVs), including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV). This application note details the critical advantage of NAT over serological assays by directly detecting viral genomic material, thereby identifying infections during the pre-seroconversion phase. Within the context of advanced viral NAT protocol research, we provide a comprehensive summary of quantitative efficacy data, detailed experimental methodologies, and essential reagent solutions to support researchers and scientists in implementing and optimizing NAT for viral pathogen screening.

The window period in viral diagnostics is the critical time interval between infection and the detectability of a pathogen by a specific assay. During this period, traditional serological tests, which rely on detecting host-generated antibodies (e.g., anti-HCV, anti-HIV) or viral antigens (e.g., HBsAg, HIV p24), yield false-negative results despite the individual being infectious [7]. This gap represented a significant residual risk for transfusion-transmitted infections.

The introduction of Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing (NAT) marked a paradigm shift. By directly targeting and amplifying viral nucleic acids (RNA or DNA), NAT can detect the presence of a pathogen days to weeks before serological markers become apparent [8]. For the blood supply, this has been transformative. The mid-to-late 1990s saw the driving force for NAT implementation: the AIDS and HCV epidemics, which resulted in thousands of infections from contaminated blood products [8]. Initially adopted by plasma fractionators, NAT has since become a cornerstone for screening labile blood components worldwide, reducing the residual risk of virus transmission to almost zero [8].

This document provides a structured overview of NAT's performance data, outlines core protocols for its application in screening for HIV, HBV, and HCV, and equips researchers with the essential toolkit for its implementation.

Quantitative Data: Comparative Efficacy of NAT vs. Serology

The superior sensitivity of NAT is quantitatively demonstrated through large-scale screening studies, which reveal infections missed by serological methods.

Table 1: NAT Yield in Blood Donor Screening: Detection of Serology-Negative Infections

| Virus | Study Location (Sample Size) | Serology-Negative, NAT-Positive Yield (per million donations) | Probable Interpretation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV | Germany (430,000 donations) | 51.2 | Early acute infection (Window Period) | [8] |

| HBV | China, Zhejiang (1.16 million donations) | 624.6 - 1669.5 | Window Period & Occult HBV Infection (OBI) | [9] |

| HIV | Egypt (87,620 donations) | 0.2 | Early acute infection (Window Period) | [7] |

These "NAT yield" cases represent donations that were infectious but would have been released for transfusion if relying solely on serological testing. A recent comparative analysis from Egypt further underscores the accuracy of NAT, showing near-perfect agreement with chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) but with the distinct advantage of identifying pre-seroconversion and occult infections [7].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of CLIA vs. NAT in Blood Donor Screening (n=87,620)

| Virus | CLIA Reactive | NAT Reactive | True Positive | False Positive (CLIA) | False Negative (CLIA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | 676 | 621 | 589 | 87 | 32 |

| HCV | 1,477 | 1,328 | 1,305 | 172 | 23 |

| HIV | 22 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 0 |

| Accuracy (CLIA vs NAT) | HBV: 99.86% | HCV: 99.78% | HIV: 100% |

Data adapted from a study in two Egyptian university blood transfusion centers [7].

Experimental Protocols

Core NAT Screening Workflow for HIV, HBV, and HCV

The following protocol outlines the standard operating procedure for multiplex NAT screening of blood donations using automated platforms.

1. Sample Collection and Preparation

- Collection: Draw whole blood from voluntary donors into sterile collection tubes containing EDTA or other appropriate anticoagulants.

- Processing: Centrifuge blood samples to separate plasma within 24 hours of collection. Store plasma at 2-8°C if testing within 48 hours; otherwise, freeze at ≤ -20°C.

- Quality Check: Ensure samples are non-hemolyzed and non-lipemic.

2. Nucleic Acid Extraction and Purification

- Method: Utilize automated nucleic acid extraction systems (e.g., on the Cobas S201 or 6800/8800 systems).

- Procedure: Extract viral nucleic acid (RNA/DNA) from 500 µL to 1 mL of plasma sample using magnetic bead-based or silica membrane-based kits. The process includes lysis, binding, washing, and elution steps. The final elution volume is typically 50-100 µL.

- Internal Control: Co-extract an exogenous Internal Control (IC) added to each sample lysis buffer to monitor extraction efficiency and detect PCR inhibition.

3. Target Amplification and Detection (Real-Time PCR/TMA)

- Technology Choice A (Real-Time PCR):

- Reverse Transcription (for HIV/HCV): Convert viral RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase and specific primers or a blend of random hexamers and target-specific primers.

- Amplification: Perform multiplex real-time PCR using target-specific primers and probes for HBV DNA, HCV RNA, and HIV RNA. Probes are labeled with different fluorophores (e.g., FAM for HBV, HEX/VIC for HCV, Cy5 for HIV).

- Detection: Monitor fluorescence in real-time. A signal that crosses the threshold cycle (Ct) within the validated range indicates a reactive sample.

- Technology Choice B (Transcription-Mediated Amplification - TMA):

- Primer Binding: Specific primers target the rRNA or mRNA of the viruses.

- Amplification: Utilize reverse transcriptase to create a DNA copy, followed by RNA polymerase to generate multiple RNA amplicons.

- Detection: Use hybridization protection assay (HPA) or other chemiluminescent methods to detect amplicons.

4. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Software Analysis: The platform's integrated software automatically analyzes amplification curves and calculates Ct values.

- Interpretation:

- Non-Reactive: No amplification curve for any viral target, with valid IC amplification.

- Reactive: Specific amplification curve for one or more viral targets, with valid IC amplification.

- Invalid: Failure of the IC amplification, requiring sample retest.

5. Confirmatory and Discriminatory Testing

- Procedure: Initially reactive samples are retested in duplicate from the original specimen.

- Discrimination: Reactive samples are tested with discriminatory NAT assays (single-plex or duplex) to identify the specific virus(es) present.

- Serological Correlation: NAT-reactive samples are further investigated with supplementary serological (e.g., CLIA, ECLIA) and viral load assays to characterize the infection stage (e.g., window period, OBI) [10] [9].

Supplementary Serological Characterization

- Objective: To determine the serological profile of NAT yield samples.

- Method: Use Chemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay (CMIA) on platforms like the ARCHITECT i2000SR or Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay (ECLIA) on Cobas e601 analyzers.

- Targets:

- HBV Profile: HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg, anti-HBe, anti-HBc.

- HCV Profile: Anti-HCV.

- HIV Profile: HIV Ag/Ab combo.

- Interpretation: NAT+/HBsAg- samples are classified as OBI; NAT+/anti-HCV- or NAT+/HIV Ag/Ab- samples are classified as window period infections [9].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

NAT Screening Algorithm and Window Period Advantage

The following diagram illustrates the integrated NAT and serology screening algorithm and the relative reduction in the window period.

NAT Yield Characterization Pathway

The diagram below outlines the logical pathway for characterizing a NAT-reactive, serology-negative donation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Viral NAT Screening

| Item | Function & Application | Example Products / Kits |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex NAT Assay Kits | For simultaneous detection and discrimination of HIV, HBV, and HCV nucleic acids in a single reaction. The core reagent for screening. | Cobas MPX (Roche), Procleix Ultrio Elite (Grifols) |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | For automated isolation and purification of viral DNA and RNA from plasma samples. Critical for removing inhibitors and concentrating target. | Cobas MPX Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (Roche), MagNA Pure LC Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche) |

| Internal Controls | Non-infectious, exogenous nucleic acid sequences added to each sample to monitor extraction efficiency, reverse transcription, and amplification; crucial for validating negative results. | Included in commercial NAT kits (e.g., Cobas MPX) |

| Quantitative Viral Load Assays | For determining the concentration of viral nucleic acid (IU/mL) in a reactive sample; used for confirmatory testing and infection characterization. | Cobas TaqMan HBV Test (Roche), RealTime HCV Assay (Abbott) |

| Supplementary Serology Assays | For comprehensive serological profiling (antigens and antibodies) of NAT yield samples to distinguish window period from occult infections. | ARCHITECT HBsAg Qualitative, ARCHITECT Anti-HCV, ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo (Abbott), Elecsys assays (Roche) |

| Quality Control Panels | Characterized positive and negative control materials used to validate assay performance, precision, and limit of detection during test runs. | WHO International Standards, Commercial Seroconversion Panels (SeraCare) |

Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) has established itself as the gold standard for confirming active infection and enabling early diagnosis across numerous viral pathogens. This status is predicated on its direct detection of pathogen genetic material, providing exceptional sensitivity and specificity that surpasses traditional serological methods. The technology, primarily based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR), identifies DNA and RNA molecules of infectious agents at a very early stage of infection, often during the window period before antibody responses develop [11]. This capability is critical for patient outcomes and public health safety, particularly in blood and plasma donation screening, where over 60 million donations are tested daily on Roche NAT systems alone [11]. The applications of NAT extend beyond HIV, hepatitis, and other well-established targets to emerging threats like Zika virus, malaria, and babesia, demonstrating its versatile role in contemporary diagnostic paradigms [11].

Performance Data: Quantitative Analysis of NAT Applications

The superior performance of NAT is quantifiable across multiple clinical scenarios, from early infant diagnosis to blood safety screening. The following tables consolidate key performance metrics from recent research and commercial implementations.

Table 1: Clinical Impact of Early Infant Diagnosis (EID) for HIV Using NAT

| Metric | Study Findings | Significance/Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| MTCT Risk | OR: 2.9 (95% CI: 1.8-4.6) for infants without EID/ART [12] | Significantly higher transmission risk without early testing and treatment. |

| HIV Prevalence | 6.8% (95% CI: 5.2-8.4%) with early ART vs. 18.4% (95% CI: 16.0-20.8%) without [12] | Early diagnosis and treatment reduce infection prevalence in exposed infants. |

| Mortality Risk | OR: 0.24 (95% CI: 0.18-0.32) for mortality with early ART (within 3 months) [12] | 76% lower mortality risk with early diagnosis and treatment initiation. |

| Timely Testing (Nigeria) | Only 35% of exposed infants tested within recommended time frame [12] | Highlights significant implementation gap in resource-limited settings. |

| POC Testing Impact (Kenya) | OR: 2.7 (95% CI: 1.9-3.8) for receiving EID within 6 weeks with POC NAT [12] | Point-of-care NAT significantly increases uptake of early testing. |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Select Commercial NAT Assays

| Assay Name | Target Pathogens | Key Performance Features |

|---|---|---|

| cobas MPX | HIV-1 (Group M, O), HIV-2, HCV, HBV [11] | Detects/discriminates 3 viruses/5 targets in one assay; boosts operational efficiency. |

| cobas WNV | West Nile Virus (Lineages 1 & 2) [11] | Direct RNA detection early in infection lifecycle. |

| cobas Malaria | Plasmodium DNA and RNA [11] | Qualitative in-vitro test for malaria in whole blood. |

| cobas DPX | Parvovirus B19 (Genotypes 1-3), HAV (Genotypes I-III) [11] | Precise B19V DNA quantitation; high HAV RNA sensitivity; uses WHO traceable standard. |

| cobas Babesia | B. microti, B. duncani, B. divergens, B. venatorum [11] | First whole blood PCR test for Babesia screening. |

| cobas Zika | Zika Virus (Asian & African strains) [11] | High clinical sensitivity; FDA-approved for donor screening. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Early Infant Diagnosis of HIV Using Dried Blood Spots and Centralized PCR

Principle: This protocol utilizes the collection of dried blood spot (DBS) samples from HIV-exposed infants for transport to a centralized laboratory where PCR-based NAT detects HIV proviral DNA or RNA [12].

Materials:

- Collection Cards: Specially treated filter paper for blood collection.

- Sterile Lancet: For heel or finger stick in infants.

- Desiccant Packs: For drying and storing DBS samples.

- Sealable Plastic Bags: For protection of samples during transport.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit: For isolation of HIV nucleic acids from DBS.

- PCR Master Mix: Contains enzymes, nucleotides, and buffer for amplification.

- HIV-specific Primers/Probes: Target conserved regions of the HIV genome (e.g., pol or gag).

- Real-time PCR Instrument: For amplification and detection.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection (Week 4-6 after birth):

- Clean the infant's heel and perform a skin puncture with a sterile lancet.

- Touch the filter paper card to the blood droplet, fully saturating multiple circles.

- Air-dry the DBS card horizontally for at least 4 hours in a dust-free environment.

Sample Storage & Transport:

- Place the dried card in a sealable bag with a desiccant pack.

- Store at 2-8°C if processing within a week; for longer storage, keep at -20°C.

- Transport to the central testing laboratory via a cool chain if necessary.

Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Punch a defined disc from the DBS into a microcentrifuge tube.

- Lyse cells and release nucleic acids using a proprietary lysis buffer.

- Purify DNA/RNA using the provided kit's magnetic beads or column-based system.

- Elute the purified nucleic acid in a small volume of nuclease-free water.

PCR Amplification & Detection:

- Prepare the reaction mix on ice: Master Mix, primers/probes, and template nucleic acid.

- Load the plate into the real-time PCR instrument.

- Run the thermocycling protocol per assay specifications (e.g., 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min).

- Fluorescence is measured at the end of each annealing/extension cycle.

Result Interpretation:

- A positive result is indicated if the fluorescence signal crosses the threshold within the pre-defined cycle number, confirming HIV infection.

- The internal control must be positive for the result to be valid.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Blood Donor Screening on Automated NAT Systems

Principle: This protocol describes the use of fully automated, high-throughput NAT systems (e.g., cobas 6800/8800 Systems) for screening individual donations or mini-pools for multiple transfusion-transmissible infections simultaneously, ensuring blood supply safety [11].

Materials:

- Automated NAT System: (e.g., cobas 6800/8800 Systems) for integrated sample processing.

- Multiplex NAT Assay: (e.g., cobas MPX assay) for simultaneous detection of HIV, HBV, and HCV.

- Sample Tubes: Primary collection tubes or secondary tubes for plasma.

- Reagent Cassettes: Pre-filled, ready-to-use, stabilized PCR reagents with RFID tracking.

- Pipette Tips & Reaction Plates: (Often provided as part of a disposable kit).

- External Controls: For quality control (positive and negative).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation & Loading:

- Centrifuge blood collection tubes to separate plasma.

- Load primary sample tubes or aliquoted plasma samples directly into the system's sample rack.

- For pooled testing, the system can automatically combine aliquots from multiple donations (e.g., 6, 24, or 96 donations).

System Setup:

- Load the reagent cassettes and disposable tips/plates into their designated bays.

- The system's RFID reader automatically identifies and tracks reagent lots and expiration.

Automated Processing:

- The system automatically performs all subsequent steps:

- Sample Transfer: Metrically transfers sample (or pool) to a reaction plate.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Uses magnetic bead technology to isolate and purify nucleic acids from the plasma.

- Elution & Master Mix Setup: Elutes nucleic acids into a small volume and combines them with the PCR master mix from the reagent cassette.

- Plate Loading & Amplification: Transfers the final reaction mix to the PCR plate and initiates real-time PCR amplification.

- The system automatically performs all subsequent steps:

Amplification & Detection:

- The thermocycler runs a pre-programmed protocol with real-time fluorescence monitoring.

- The software automatically analyzes the amplification curves for each target channel.

Result Reporting & Data Management:

- The software assigns a final result (e.g., Target Not Detected, Target Detected, or Invalid) for each sample and target.

- Results, along with full process traceability data, are transmitted to the Laboratory Information System (LIS).

- For reactive samples, the system can automatically perform reflexive discriminatory testing.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NAT Protocols

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex NAT Assays | Simultaneously detects multiple pathogens from a single sample, increasing throughput and efficiency. | cobas MPX for HIV-1/HIV-2/HCV/HBV in one test [11]. |

| Stabilized PCR Reagents | Ready-to-use reagents that do not require thawing, mixing, or calibration, reducing hands-on time and errors. | Stabilized real-time PCR reagents on platforms like cobas 6800 [11]. |

| Internal Controls | Non-target nucleic acid sequence added to each sample to monitor extraction efficiency and PCR inhibition. | Full-process internal controls help ensure result integrity [11]. |

| External Positive Controls | Separate samples with known, quantified target used for run validation and calibration. | True external positive controls that do not affect assay calibration [11]. |

| Dried Blood Spot (DBS) Cards | Filter paper cards for simple collection, stabilization, and transport of blood samples. | Enables EID in remote areas; requires specific punching and elution protocols [12]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Reagents for lysing cells and purifying DNA/RNA, free of inhibitors, for downstream PCR. | Can be manual (columns/magnetic beads) or integrated into automated systems. |

| Pathogen-Specific Primers/Probes | Short, designed nucleic acid sequences that bind to and enable detection of a specific pathogen's genome. | Critical for assay specificity; must target conserved regions to ensure broad detection. |

Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) has revolutionized the detection and management of viral infections by offering unparalleled sensitivity and specificity. These molecular diagnostics are critical tools for public health, from tracking the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants to ensuring the safety of the global blood supply against pathogens like HIV, Hepatitis B (HBV), and Hepatitis C (HCV). This application note provides a detailed comparison of NAT applications across respiratory and blood-borne viruses, summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies, and outlines standardized protocols for implementing these assays in research and clinical settings. The guidance is framed within the broader context of developing robust viral NAT protocols for both epidemic response and routine surveillance.

NAT Workflow and Quantitative Data Analysis

The core NAT workflow, from sample collection to result interpretation, is universally applicable across viral targets, though specific reagents and targets differ. The following diagram illustrates the generalized pathway for viral detection using nucleic acid amplification.

Comparative Analysis of NAT Detection Rates

The utility of NAT is particularly evident in its ability to detect infections during the serological window period. The following table synthesizes data from blood bank screenings, demonstrating the superior sensitivity of NAT compared to serological assays.

Table 1: Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) Yield in Seronegative Blood Donors

| Virus | Study Location | Seronegative Donors Screened (N) | NAT Reactive Cases (n) | NAT Yield Rate | Rate per Million Donors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | Karachi, Pakistan [13] | 43,215 | 19 | 0.044% | 1 in 2,252 |

| HCV | Karachi, Pakistan [13] | 43,215 | 4 | 0.009% | 1 in 11,111 |

| HIV | Karachi, Pakistan [13] | 43,215 | 0 | 0.000% | 0 |

| HIV | Maputo & Beira, Mozambique [14] | 2,656 | 12 | 0.452%* | 4,518 |

| HBV | Maputo & Beira, Mozambique [14] | 2,659 | 21 | 0.790%* | 7,897 |

*The higher prevalence rates in Mozambique reflect regional endemicity and highlight the critical need for NAT implementation in high-burden areas.

SARS-CoV-2 Test Attributes and Variant Resilience

For respiratory pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, assay design is critical for maintaining detection accuracy in the face of an evolving viral genome. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) categorizes molecular tests based on their target design, which directly impacts their resilience to viral mutations [15].

Table 2: SARS-CoV-2 Molecular Diagnostic Test Attributes (Selected FDA-Authorized Assays)

| Test Name (Manufacturer/Developer) | Technology | Authorized Settings | Key Attributes | Variant Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3EO Health COVID-19 Test | RT-LAMP | Home, OTC | Multiple Targets, Over the Counter | More likely to perform well |

| Metrix COVID-19 Test | RT-LAMP | Home, H, M, W | Saliva, Screening, Multiple Targets | More likely to perform well |

| Xpert Xpress CoV-2/Flu/RSV plus (Cepheid) | Real-time RT-PCR | H, M, W | Multi-analyte, Multiple Targets | More likely to perform well |

| CDC 2019-nCoV RT-PCR Panel | Real-time RT-PCR | H | Pooling, Multiple Targets | More likely to perform well |

| Revogene SARS-CoV-2 | Real-time RT-PCR | H, M | Single Target | More susceptible to performance changes |

Detailed NAT Protocols

Protocol: Blood-Borne Virus Screening in Blood Donations

This protocol details the mini-pool NAT strategy used in high-throughput blood bank settings, as described in recent studies [13] [14].

1. Sample Collection and Preparation

- Collect whole blood from donors in K3EDTA vacuum tubes.

- Centrifuge at 800-1600 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Carefully aspirate plasma, ensuring no cellular material is transferred.

- Store plasma aliquots at -20°C or lower until testing.

2. Serological Screening (Initial Triage)

- Screen all donor samples for HIV (Ab/Ag), HBsAg, and anti-HCV using FDA-approved/CE-marked immunoassays (e.g., ECLIA on Roche cobas e 601 analyzer).

- Exclusion Criteria: Discard units reactive in initial and confirmatory serological testing.

- Inclusion for NAT: Proceed with serologically non-reactive samples for nucleic acid testing.

3. Mini-Pool Nucleic Acid Testing (MP-NAT)

- Pool Formation: Combine 100 µL of plasma from 6 different seronegative donors to create a mini-pool.

- Nucleic Acid Extraction & Amplification: Use an integrated extraction/amplification system (e.g., cobas s 201 system) with a multiplexed assay (e.g., cobas TaqScreen MPX test v2.0) to detect HIV-1 RNA, HIV-2 RNA, HBV DNA, and HCV RNA simultaneously.

- Run internal controls as specified by the manufacturer with each batch.

4. Resolution Testing

- If a mini-pool tests reactive, deconstruct the pool and test each individual donor sample from that pool separately using the same NAT assay.

- The individual sample(s) that are reactive in the resolution testing are considered confirmed NAT-yield infections.

- Safely discard the corresponding blood products.

Protocol: Multiplex Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens

This protocol is adapted for detecting SARS-CoV-2 and co-circulating respiratory viruses, which is crucial for differential diagnosis [3] [15].

1. Sample Collection (Multiple Options)

- Nasopharyngeal/Nasal Swab: Insert swab into nostril, reaching the posterior nasopharynx. Swab with several rotations and place into viral transport media (VTM).

- Saliva Collection: Have the patient drool directly into a sterile collection tube, collecting at least 1-2 mL. Saliva samples can often be used with minimal processing.

2. Sample Inactivation and Lysis

- For swab samples in VTM or raw saliva, add an equal volume of proteinase K-containing lysis buffer.

- Incubate at 65°C for 15-30 minutes to inactivate the virus and release RNA.

3. Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Use automated magnetic bead-based extraction systems (e.g., on KingFisher or QIAcube platforms) or column-based kits.

- Elution: Elute purified RNA in 50-100 µL of nuclease-free water or the provided elution buffer.

- Critical Step: Include an exogenous internal control (e.g., MS2 phage) added to the lysis buffer to monitor extraction efficiency and PCR inhibition.

4. Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing:

- Reverse transcriptase enzyme

- Hot-start DNA polymerase

- dNTPs

- Primers and probes targeting multiple SARS-CoV-2 genes (e.g., E gene, N gene, RdRP gene). For multiplex panels, include primers/probes for influenza A/B, RSV, etc.

- Probe Chemistry: Use TaqMan probes with distinct fluorophores (e.g., FAM, HEX, Cy5) for each target.

- Thermocycling Conditions (Example):

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 10-15 minutes.

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes.

- 45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (acquire fluorescence).

- Analysis: Determine the cycle threshold (Ct) value for each target. A sample is considered positive if it produces a specific amplification curve with a Ct value below the validated cutoff.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of NAT protocols relies on a suite of reliable reagents and instruments. The following table catalogs essential solutions referenced in the featured studies and regulatory documents.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Platforms for Viral Nucleic Acid Testing

| Research Reagent Solution | Specific Example(s) | Function in NAT Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex NAAT Assay | cobas TaqScreen MPX test v2.0 (Roche) [13] | Simultaneously detects and differentiates HIV-1, HIV-2, HBV, and HCV in a single tube. |

| Automated NAAT Platform | cobas s 201 system (Roche) [13], Xpert Xpress (Cepheid) [15] | Integrated system for automated nucleic acid extraction, amplification, and detection. |

| Serology Confirmation Assay | GENSCREEN PLUS HIV Ag-Ab (Bio-Rad), Advanced Quality HBsAg ELISA (InTec) [14] | Immunoassay for initial serological screening of blood donations. |

| Isothermal Amplification Mix | LAMP (Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification) kits [15] | Amplifies nucleic acids at a constant temperature, enabling simpler device design for point-of-care/home testing. |

| CRISPR-Cas Detection | SHERLOCK, DETECTR [3] [16] | Provides highly specific and sensitive sequence detection, often coupled with isothermal amplification. |

| Sample Collection Kit | Home Collection Kits (e.g., SalivaDirect DTC Kit) [15] | Enables stable self-collection and transport of patient samples for laboratory testing. |

| Internal Control | Exogenous Non-infectious RNA (e.g., MS2 phage) | Added to each sample during lysis to monitor nucleic acid extraction efficiency and rule out PCR inhibition. |

Discussion and Technical Notes

The data and protocols presented herein underscore the pivotal role of NAT in modern virology. The quantitative findings from Pakistan and Mozambique reveal a residual risk of transfusion-transmitted infections that can only be mitigated by the implementation of NAT, as it reliably shortens the diagnostic window period [13] [14]. For respiratory pathogens, the COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed the development of diverse platforms, from lab-based RT-PCR to point-of-care and even home-based isothermal tests (e.g., LAMP), greatly expanding testing accessibility [3] [15].

A key consideration for any NAT assay is primer and probe design. As evidenced by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, viruses with high mutation rates can acquire mutations that lead to "target failure" (e.g., S-gene target failure associated with the Omicron variant). Therefore, assays with multiple genetic targets are strongly recommended over single-target tests for novel or rapidly evolving viruses, as they are more likely to maintain diagnostic accuracy against emerging variants [16] [15].

Future directions in the field point toward the integration of isothermal amplification techniques (like RPA and LAMP) with CRISPR-Cas detection systems. These platforms aim to provide sensitivity and specificity rivaling RT-PCR while being faster, equipment-free, and more deployable in low-resource settings, aligning with the WHO's "REASSURED" criteria for ideal diagnostics [3].

Transfusion-transmitted infections (TTIs) represent a major hazard to blood recipients globally, with Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) being among the most significant threats [7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has established the goal of eliminating TTIs by implementing rigorous screening of blood donations, targeting a zero-risk blood supply by 2030 [7]. While traditional serological testing methods, such as chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA), have been foundational in blood screening, they primarily detect the immune response to pathogens rather than the presence of the virus itself [7]. Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) has emerged as a critical advancement, enabling the direct detection of viral nucleic acids and significantly reducing the diagnostic window period between infection and detectability [7] [17]. This application note details the role of NAT within the broader context of viral nucleic acid testing protocols research, providing a comparative performance analysis, detailed experimental methodologies, and implementation protocols to enhance blood safety for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Performance Analysis: NAT Versus Serological Testing

Comparative Detection Rates

The superior sensitivity of NAT directly translates into the identification of additional infectious units that serological testing misses, thereby enhancing the safety of the blood supply. These "NAT yield" cases are particularly important as they represent donations from donors in the early, pre-seroconversion stage of infection. A large-scale retrospective analysis of 87,620 blood specimens from voluntary donors compared the detection rates of CLIA and NAT [7].

Table 1: Comparative Detection Rates of CLIA and NAT in Blood Donor Screening

| Virus | Total Reactive by CLIA | Total Reactive by NAT | True Positives | False Positives (CLIA) | False Negatives (CLIA) | NAT Yield (Additional Cases Detected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | 676 | 621 | 589 | 87 | 32 | 32 |

| HCV | 1,477 | 1,328 | 1,305 | 172 | 23 | 23 |

| HIV | 22 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2,175 | 1,968 | 1,913 | 262 | 55 | 55 |

Data adapted from a retrospective analysis of 87,620 specimens [7].

The data demonstrates that NAT detected 55 infectious donations (32 for HBV and 23 for HCV) that were missed by CLIA screening. These represent the critical "window period" infections where the donor is infectious but has not yet developed detectable antibodies or antigens. Furthermore, CLIA exhibited a substantial number of false-positive results (262 across the three viruses), which can lead to unnecessary disposal of safe blood units and deferral of healthy donors [7].

Another study involving 30,335 blood donations provided further evidence of NAT's superior sensitivity and specificity [17].

Table 2: Diagnostic Accuracy of NAT and CLIA for TTI Screening

| Virus | Metric | NAT | CLIA |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | Sensitivity | 98.50% | 79.09% |

| Specificity | 98.00% | ~72.9%* | |

| HCV | Sensitivity | 97.50% | 64.20% |

| Specificity | 98.00% | ~83.5%* | |

| HIV | Sensitivity | 98.00% | 94.44% |

| Specificity | 98.50% | ~94.3%* |

* Calculated based on false positive rates reported in [17].

Statistical Agreement and Clinical Impact

Despite the differences in sensitivity, studies show a high statistical agreement between NAT and CLIA. The agreement, measured using the kappa statistic, was nearly perfect: 0.929 for HCV, 0.907 for HBV, and 0.900 for HIV [7]. This indicates that while NAT is more sensitive, the two tests are generally consistent in their findings.

The implementation of NAT, therefore, has a direct and measurable impact on blood transfusion safety. By identifying window-period and occult infections, NAT significantly reduces the residual risk of TTIs. The cost-effectiveness of NAT is particularly pronounced for HBV and HCV, though it can be less so for HIV due to the already high sensitivity of CLIA for this virus [17].

Experimental Protocol for NAT in Blood Screening

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for screening plasma from blood donations for HBV, HCV, and HIV using a multiplexed NAT approach on a high-throughput automated system [7].

Principle

The protocol is based on the automated extraction, purification, and reverse transcription of viral nucleic acids (RNA and DNA) from individual donor plasma samples, followed by simultaneous amplification and detection of conserved target sequences for HIV, HCV, and HBV using multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology. The process includes an internal control to monitor for potential inhibition [7].

Specimen Collection and Preparation

- Collection: Collect whole blood from voluntary non-remunerated blood donors using sterile collection bags containing an appropriate anticoagulant (e.g., CPDA-1).

- Processing: Within 6 hours of collection, centrifuge the whole blood at a minimum of 5,000 × g for 5 minutes at room temperature to separate plasma.

- Aliquoting: Aseptically transfer at least 2 mL of plasma into a labelled, sterile, nuclease-free primary tube.

- Storage: If testing is not immediate, store plasma specimens at 2–8°C for up to 72 hours. For longer storage, freeze at -20°C or below and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NAT Screening

| Item | Function | Specification / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma Specimen | Source of viral nucleic acid for detection. | Human EDTA or CPDA plasma, visually clear and non-lipemic. |

| Nucleic Acid Test Kit | Multiplex assay for simultaneous pathogen detection. | Qualitative multiplex test (e.g., cobas MPX test) for HIV-1 RNA, HCV RNA, and HBV DNA. |

| Internal Control | Monitors the entire process from extraction to amplification for inhibition. | Non-infectious, exogenous RNA/DNA sequence provided in the assay kit. |

| Lysis Buffer | Inactivates virus and releases nucleic acids. | Contains chaotropic salts and detergents. |

| Wash Buffers | Remove impurities and inhibitors during nucleic acid purification. | Ethanol-based buffers of varying ionic strength. |

| Elution Buffer | Final resuspension of purified nucleic acids. | Low-salt buffer or nuclease-free water. |

| Enzyme Master Mix | Amplifies and detects target sequences. | Contains reverse transcriptase, Taq polymerase, primers, and probes for multiplex PCR. |

| Automated Analyzer | Integrates and automates all steps of the NAT process. | System with sample supply, transfer, processing, and analytical modules (e.g., Cobas 6800/8800 systems). |

Procedure

The following workflow outlines the key steps in the NAT screening process, from sample preparation to result interpretation.

- System Initialization: Power on the automated nucleic acid testing system (e.g., Cobas 6800/8800). Initialize the system using manufacturer-defined procedures, which include priming the fluidic system and performing start-up checks.

- Reagent and Sample Loading: Load the pre-packaged reagent cassettes (containing lysis, wash, and elution buffers) and the enzyme master mix onto their designated positions in the analyzer. Place primary sample tubes in the sample racks and load them into the system.

- Automated Nucleic Acid Extraction and Purification:

- The system automatically aliquots the patient plasma and combines it with the lysis buffer, which inactivates the virus and releases nucleic acids.

- Nucleic acids are bound to a solid-phase magnetic particle in the presence of a chaotropic salt.

- Magnetic separation and multiple wash steps are performed to remove proteins, salts, and other potential inhibitors.

- Purified nucleic acids are eluted into a small volume of elution buffer.

- Amplification and Detection:

- The eluate containing the purified nucleic acids is automatically transferred to a new reaction vessel and mixed with the enzyme master mix.

- The reaction plate is transferred to the thermocycler module.

- The multiplex real-time PCR protocol is executed:

- Reverse Transcription (if applicable): 50°C for 15 minutes (for RNA viruses HIV and HCV).

- PCR Activation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- Amplification (45-50 cycles): Denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, then combined annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 seconds with fluorescent signal acquisition.

- Result Analysis and Interpretation: The system's software analyzes the amplification curves for each target (HBV, HCV, HIV) and the internal control. Results are automatically assigned as follows:

- Non-Reactive: No amplification curve is detected for any viral target, and the internal control amplifies as expected.

- Reactive: A specific amplification curve is detected for one or more viral targets.

- Invalid: The internal control fails to amplify, indicating potential inhibition or a processing error. The specimen must be retested.

Quality Control and Troubleshooting

- Quality Control: The internal control in each specimen is the primary quality control measure. Additionally, external positive and negative controls should be run with each batch of samples as per the laboratory's quality management system [7].

- Troubleshooting Invalid Results: For invalid results due to internal control failure, repeat the test with the original specimen. If the failure persists, re-collect the sample if possible [18].

- Resolving Discrepant Results: In cases where NAT is reactive but CLIA is non-reactive (false-negative CLIA), the result is interpreted as a true NAT yield, indicating an early infection. When CLIA is reactive but NAT is non-reactive (false-positive CLIA), it may indicate a prior, cleared infection, the presence of cross-reacting antibodies, or, in the case of HBV, a transient positive HBsAg after vaccination [7]. Supplementary tests (e.g., neutralization assays, alternative NAT assays) are recommended for confirmation.

Nucleic Acid Testing represents a fundamental advancement in the paradigm of blood safety, moving beyond serological markers to direct, sequence-specific detection of viral pathogens [7]. The quantitative data and detailed protocol presented herein underscore NAT's critical role in minimizing the residual risk of TTIs by closing the diagnostic window period and identifying occult infections. Its high sensitivity and specificity, combined with the high-throughput capabilities of modern automated systems, make it an indispensable tool for blood transfusion centers. The adoption and continuous refinement of NAT protocols, as part of a layered screening approach that includes careful donor selection and serological testing, are essential to achieving the global goal of a zero-risk blood supply.

Methodologies and Workflow Implementation in NAT Systems

Viral nucleic acid testing (NAT) is a cornerstone of modern molecular diagnostics, virology research, and therapeutic development. The selection of an appropriate amplification technique is critical for achieving the desired sensitivity, specificity, speed, and practicality for a given application. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of four core amplification technologies: Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP), Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA), and Transcription-Mediated Amplification (TMA). It is structured within a broader research context on viral NAT protocols, providing researchers and drug development professionals with consolidated data, standardized protocols, and visual workflows to inform experimental design and implementation.

Technology Comparison and Quantitative Data

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of the four featured amplification technologies, providing a basis for initial technology selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Viral Nucleic Acid Amplification Technologies

| Feature | qRT-PCR | LAMP | RPA | TMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Principle | PCR-based thermal cycling | Isothermal strand displacement | Isothermal recombinase-driven primer insertion | Isothermal transcription-based amplification |

| Primary Target | RNA (via cDNA synthesis) | DNA/RNA (with reverse transcriptase) | DNA/RNA (with reverse transcriptase) | RNA |

| Typical Reaction Temperature | 55-95°C (cycling) | 60-65°C | 37-42°C | 41-42°C [19] |

| Typical Assay Time | 1.5 - 2 hours | 15 - 60 minutes [20] [19] | 10 - 20 minutes [21] | < 2 hours [19] |

| Key Enzymes | Reverse Transcriptase, Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Bst DNA Polymerase (strand-displacing) | Recombinase, Single-Stranded DNA-Binding Protein, Strand-Displacing Polymerase | Reverse Transcriptase, RNA Polymerase [19] |

| Primer System | 2 primers | 4-6 primers [19] | 2 primers | 2 primers and 1 probe [19] |

| Detection Methods | Fluorescent probes (e.g., TaqMan) or intercalating dyes | Turbidity, colorimetry, fluorescent dyes [19] | Fluorescent probes or intercalating dyes | Turbidity, colorimetry, fluorescent probes [19] |

| Relative Sensitivity | High (detects down to a few copies) | High [19] | High (single-copy detection) [19] | Very High [19] |

| Instrument Requirement | Thermal Cycler with fluorescence detection | Simple Heater/Block | Simple Heater/Block | Automated or simple heater system |

| Key Advantage | Quantitative, gold standard, highly sensitive | Simple instrumentation, rapid, visual detection | Rapid, low-temperature operation | High sensitivity, specific for RNA |

| Key Limitation | Requires expensive thermal cycler | Primer design complexity, multiplexing challenges | Cost of proprietary enzymes, limited multiplexing | Commercial kit dependency |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: One-Step qRT-PCR for Viral RNA Detection

This protocol is adapted for the sensitive and quantitative detection of viral RNA, such as SARS-CoV-2, using a one-step master mix [22].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- One-Step qRT-PCR Master Mix: Contains reverse transcriptase, hot-start DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer.

- Virus-Specific Primers and Probe: Designed against a conserved region of the viral genome (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 N gene). The probe is dual-labeled with a 5' fluorophore (e.g., FAM) and a 3' quencher.

- Nuclease-Free Water: To adjust reaction volume.

- RNA Template: Purified viral RNA or extracted nucleic acid from clinical samples (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs).

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: On ice, prepare a 20 µL reaction mix containing:

- 10 µL of 2X One-Step qRT-PCR Master Mix

- 1 µL of 20X Primer/Probe Mix (final concentration: 500 nM primers, 250 nM probe)

- Up to 5 µL of RNA template

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL

- Thermal Cycling: Load the plate into a real-time PCR instrument and run the following program:

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 10-15 minutes.

- Enzyme Activation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- Amplification (40-45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 55-60°C for 30-60 seconds (acquire fluorescence).

- Data Analysis: Determine the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value for each sample. Quantify the viral load by comparing Ct values to a standard curve of known copy numbers.

Protocol 2: Reverse Transcriptase-LAMP (RT-LAMP) for Point-of-Care Viral Detection

This protocol describes a colorimetric RT-LAMP assay suitable for rapid, visual detection of viruses like SARS-CoV-2 in resource-limited settings [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Bst DNA Polymerase (or similar strand-displacing polymerase): The core enzyme for isothermal amplification.

- Reverse Transcriptase: For cDNA synthesis from viral RNA.

- LAMP Primer Set: A set of 4-6 primers (F3, B3, FIP, BIP, Loop F, Loop B) targeting the viral genome.

- dNTPs: Deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates.

- WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP Master Mix: Contains a phenol red pH indicator.

- RNA Template: Purified or crude lysate.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 25 µL reaction mix containing:

- 12.5 µL of 2X WarmStart Colorimetric LAMP Master Mix

- 1.5 µL of 10X LAMP Primer Mix

- 1 µL of Reverse Transcriptase (if not included in the master mix)

- 2-5 µL of RNA template

- Nuclease-free water to 25 µL

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction tube in a heat block or water bath at a constant 60-65°C for 15-30 minutes.

- Detection: Visually observe the color change.

- Positive: Yellow (acidic pH due to pyrophosphate production).

- Negative: Pink/Magenta (basic pH).

Protocol 3: RPA for Ultra-Rapid Viral Nucleic Acid Amplification

RPA is renowned for its speed and low operating temperature, making it ideal for field-deployable diagnostics [21].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- RPA Basic Kit: Contains recombinase enzymes, single-stranded DNA-binding proteins, strand-displacing polymerase, and reaction buffer.

- Virus-Specific Primers: Designed according to RPA guidelines.

- Magnesium Acetate (MgOAc): A critical cofactor that must be added to initiate the reaction.

- Fluorescent Probe (optional, for real-time detection): A exo probe (e.g., with FAM/THF/Black Hole Quencher).

Methodology:

- Rehydration: Rehydrate the RPA pellet with 29.5 µL of rehydration buffer and the provided primer mix.

- Template Addition: Add 2 µL of extracted nucleic acid template.

- Initiation: Pipette 2.5 µL of 280 mM Magnesium Acetate (MgOAc) into the tube lid. Briefly centrifuge to start the reaction.

- Incubation and Detection: Incubate the tube at 37-42°C for 10-20 minutes. For real-time detection, place the tube in a portable fluorescent reader pre-warmed to 39°C and monitor the fluorescence signal.

Protocol 4: TMA for Highly Sensitive Viral RNA Detection

TMA is an isothermal, transcription-based method known for its exceptional sensitivity in detecting RNA viruses like HIV and HCV [19].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- TMA Master Mix: Typically includes reverse transcriptase and T7 RNA polymerase.

- Target-Specific Primers: One primer contains a T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence.

- Detection Probes: Chemiluminescent or fluorescently labeled DNA probes for hybridizing to the amplified RNA amplicons.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Combine the TMA master mix, primers, and the target RNA sample in a single tube.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 41-42°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Amplification Process:

- The reverse transcriptase uses the primer with the T7 promoter to create a DNA copy of the RNA target, forming an RNA:DNA duplex.

- The RNA is degraded, and the second primer binds to the cDNA, allowing the reverse transcriptase to synthesize a double-stranded DNA molecule with a functional T7 promoter.

- T7 RNA polymerase then transcribes hundreds to thousands of RNA copies from this DNA template.

- Each of these RNA amplicons is recycled back into the process, leading to exponential, isothermal amplification.

- Detection: The amplified RNA products are typically detected using a hybridization protection assay (HPA) with chemiluminescent probes or in real-time with fluorescent probes.

Workflow and Technology Selection Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate amplification technology based on key experimental requirements.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of viral NAT protocols relies on a core set of reagents. The following table details these essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Viral Nucleic Acid Amplification

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in the Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerases | Bst DNA Polymerase (LAMP) [23], Recombinase/Polymerase Mix (RPA), T7 RNA Polymerase (TMA) [19] | Enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of new nucleic acid strands. The specific type (strand-displacing, recombinase-enabled, etc.) defines the technology. |

| Primers & Probes | TaqMan Probes (qRT-PCR), LAMP Primer Sets (F3, B3, FIP, BIP) [19], RPA exo Probes | Provide sequence specificity for targeting the viral genome. Probes enable real-time, specific detection of the amplicon. |

| Nucleotides & Cofactors | dNTPs (all methods), NTPs (TMA), Magnesium Acetate (RPA) [21] | dNTPs/NTPs are the building blocks for new DNA/RNA strands. Mg²⁺ is an essential cofactor for polymerase activity. |

| Buffer Systems | Isothermal Amplification Buffer, PCR Buffer | Provide the optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for enzyme activity and reaction specificity. |

| Detection Chemistries | SYBR Green, Phenol Red (colorimetric LAMP) [21], Chemiluminescent Probes (TMA) | Enable visualization and quantification of the amplification product through fluorescence, color change, or light emission. |

| Sample Preparation Kits | RNA Extraction Kits, Viral Lysis Buffers | Isolate and purify nucleic acids from complex clinical samples (e.g., swabs, blood), removing inhibitors. |

The choice of an amplification technology is a fundamental decision in viral NAT protocol design. qRT-PCR remains the gold standard for quantitative analysis, while isothermal methods like LAMP, RPA, and TMA offer compelling advantages in speed, simplicity, and portability for qualitative detection. LAMP is excellent for robust, visual POC tests, RPA offers unparalleled speed and low-temperature operation, and TMA provides exceptional sensitivity for RNA targets. The optimal technology depends on the specific requirements of the research or diagnostic application, including the need for quantification, available infrastructure, assay time, and the required sensitivity. Understanding the principles, protocols, and reagents outlined in this document will empower researchers and drug development professionals to select and implement the most effective viral NAT strategy.

Within the framework of viral Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) protocols, the efficiency of sample processing and nucleic acid extraction is a critical determinant of downstream assay success. This initial phase is paramount for isolating high-quality viral DNA and RNA from complex biological matrices, free from inhibitors that can compromise enzymatic reactions in techniques like quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [24] [25]. The selection of an appropriate extraction method significantly influences the sensitivity, accuracy, and reliability of viral detection and quantification, especially when dealing with low-abundance pathogens or challenging sample types such as clinical specimens and vaccine biologicals [25] [26]. This application note provides a structured evaluation of extraction efficiency and detailed protocols to support robust viral NAT in research and drug development.

Comparative Efficiency of Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

The recovery efficiency of viral nucleic acids varies considerably among different extraction technologies and commercial kits. Key differentiators include the use of proteolytic enzymes, the inclusion of carrier nucleic acids, the core binding technology (e.g., silica columns vs. magnetic beads), and the specific composition of lysis and washing buffers [24] [26].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method / Kit | Target Nucleic Acid | Key Technology / Features | Reported Efficiency / Performance | Protocol Duration (Minutes) | Sample Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invitrogen PureLink Virus RNA/DNA Kit [25] | Total NA (ssRNA, dsRNA, dsDNA) | Silica membrane column | Reproducibly higher or equal yield for a panel of viruses (EBV, Reo3, FeLV, RSV) compared to other methods [25] | ~45 [27] | Cell-free plasma, serum, cerebrospinal fluid [27] |

| QIAamp Blood DNA Kit [24] | Viral DNA | Silica column, proteolytic enzyme, carrier | High HBV DNA recovery efficiency, comparable to High Pure viral nucleic acid kit [24] | Not specified | Serum, plasma |

| High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid Kit [24] | Viral DNA/RNA | Silica column, enzyme digestion, chaotropic salts | One of the most efficient for HBV DNA recovery [24] | Not specified | Serum, plasma |

| Five-Minute Extraction (FME) Method [26] | Viral RNA/DNA | Magnetic beads, GTC lysis, glycerin/ethanol wash | Equivalent detection rate to standard magnetic bead method for IAV; high RNA concentration/purity [26] | 5 [26] | Respiratory samples (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs) [26] |

| Magnetic Bead-Based Kits (e.g., MagMAX) [27] | Viral RNA/DNA | Paramagnetic beads, chaotropic salts | High and consistent RNA yields; easily automatable; suitable for NGS [27] | 25-30 (Manual) [26] | Swabs, saliva, stool, urine, plasma, serum [27] |

| Phenol-Chloroform (TRIzol) [26] | Total RNA | Organic solvent precipitation | Lower recovery for FeLV (ssRNA) and EBV (dsDNA); risk of organic matter contamination [25] [26] | >70 [26] | Tissues, cells [26] |

A seminal study evaluating five extraction kits for viral DNA from serum highlighted that protocols incorporating a proteolytic enzyme digestion step in addition to chaotropic solutions demonstrated superior recovery of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) DNA compared to those relying on chemical disruption alone [24]. Furthermore, kits supplied with carrier nucleic acid and guaranteed to be RNase-free were noted to have the widest application in a routine microbiology laboratory [24]. More recent research underscores that methods using bind-elute technologies (silica membranes or magnetic beads) are generally adept at extracting all nucleic acid types, while precipitation techniques often show poorer recovery, particularly for single-stranded RNA viruses [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Evaluation

Protocol 1: Standardized Evaluation of Extraction Kits Using qPCR

This protocol outlines a method to compare the relative efficiencies of different nucleic acid extraction kits for recovering viral DNA and RNA from serum samples, using quantitative PCR (qPCR) on a platform like the LightCycler [24].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Begin with well-characterized sample pools. For DNA evaluation, use a serum pool with a known concentration of viral DNA (e.g., HBV DNA at 25 million genome equivalents/mL). For RNA evaluation, use a serum pool with a known concentration of viral RNA (e.g., HCV RNA at 2.5 million genome equivalents/mL). Confirm concentrations using a reference method prior to the experiment [24].

- 2. Nucleic Acid Extraction: Process aliquots of the sample pools in parallel using each extraction kit under evaluation. Strictly follow the manufacturers' instructions. To standardize comparisons, use a consistent serum volume to elution buffer volume ratio (e.g., eluting in half the original serum volume). Do not utilize optional steps like double elution [24].

- 3. Quantitative PCR (qPCR):

- HBV DNA PCR: Use a reaction mix containing SYBR Green I, primers targeting a conserved region (e.g., the core open reading frame), and a suitable Taq polymerase. Use a thermal cycling profile with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, followed by 33 cycles of 96°C for 0s, 50°C for 5s, 72°C for 15s, and a data acquisition step at 81°C for 5s [24].

- HCV RNA RT-PCR: Use a one-step RT-PCR kit. The thermal profile should include reverse transcription at 55°C for 10 minutes, initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 seconds, followed by 40 cycles of 96°C for 0s, 55°C for 5s, 72°C for 15s, and data acquisition at 88°C for 5s [24].

- 4. Data Analysis: Determine the cycle threshold (Ct) or "noise band crossing point" for each replicate. Compare the mean Ct values between kits; a later Ct indicates lower extraction efficiency. For absolute comparison, use the nucleic acid extracted by the most efficient kit to create a log10 dilution series of quantification standards. Use this standard curve to determine the relative concentration of viral nucleic acid recovered by the other kits [24].

Protocol 2: Dual-Armed Extraction for Comprehensive Viral Recovery

For broad-spectrum adventitious agent detection using HTS, a dual-armed extraction strategy is recommended to efficiently recover all viral nucleic acid types (ssRNA, dsRNA, dsDNA) from a complex cell substrate matrix [25].

- 1. Sample Lysis and Processing: Spike the model virus panel (e.g., EBV, Reo3, FeLV, RSV) into the biological matrix, such as a HeLa cell culture. Divide the lysate for parallel processing in two arms.

- 2. Arm A - Total Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract total nucleic acid using a kit demonstrated to have high and reproducible recovery for all virus types, such as the Invitrogen PureLink Virus RNA/DNA Kit. This arm ensures recovery of the full spectrum of nucleic acids [25].

- 3. Arm B - Enriched Double-Stranded Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract DNA using a kit like the Wako DNA Extractor Kit, which includes an RNase A digestion step during the initial Proteinase K digestion. This step degrades single-stranded RNA, thereby enriching for double-stranded nucleic acids (dsDNA and dsRNA) and significantly improving the recovery of viruses like mammalian orthoreovirus (Reo3) [25].

- 4. Nucleic Acid Combination and Downstream Processing: Combine the eluates from Arm A and Arm B. Convert all RNA to double-stranded DNA using a first- and second-strand synthesis protocol. This dsDNA product is then suitable for library preparation and HTS analysis. Note that Whole-Genome Amplification (WGA) should be avoided if unbiased representation is critical, as it exhibits a strong bias toward amplifying double-stranded DNA, including host cellular DNA [25].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this dual-arm strategy:

Data Analysis and Presentation for Efficiency Studies

Effective data presentation is crucial for interpreting the results of extraction efficiency studies. Quantitative data should be summarized using clearly structured tables and appropriate visualizations to highlight key findings [28].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleic Acid Extraction

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example Composition / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Solution | Disrupts viral envelopes and cells, inactivates nucleases, and releases nucleic acids. | Often contains chaotropic salts (e.g., Guanidine Thiocyanate - GTC), detergents (e.g., Sarkosyl), and reducing agents (e.g., DTT) [26]. |

| Proteolytic Enzyme | Digests proteinaceous material and aids in the disruption of viral capsids. | Proteinase K. Its inclusion significantly improves viral DNA recovery from serum [24]. |

| Binding Matrix | Selectively binds nucleic acids in high-salt conditions for separation from contaminants. | Silica (in columns or membranes) or superparamagnetic beads [24] [27]. |

| Wash Buffer | Removes proteins, salts, and other impurities from the bound nucleic acid. | Typically contains ethanol and a buffer. A novel wash solution of 50% glycerin and 50% ethanol has been validated for rapid, efficient washing [26]. |

| Elution Buffer | Releases purified nucleic acids from the binding matrix in a low-salt solution. | Low-ionic-strength buffer such as Tris-EDTA (TE) or nuclease-free water [26]. |

| Carrier Nucleic Acid | Improves the recovery efficiency of low-concentration viral nucleic acids by providing bulk for precipitation or binding. | Often included in kits designed for high-sensitivity applications [24]. |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | Protect labile RNA from degradation by ubiquitous RNases. | Included in lysis buffers and elution solutions to maintain RNA integrity [27]. |

When presenting results, bar graphs are highly effective for comparing mean values (e.g., Ct values or relative concentrations) between different extraction kits or methods. For data that shows the relationship between two continuous variables, such as input viral load and output nucleic acid concentration, scatter plots with regression lines are recommended [29] [28]. All figures and tables should be self-explanatory, with clear titles and defined footnotes for any abbreviations or statistical annotations [28].

The rigorous evaluation of nucleic acid extraction efficiency is a foundational step in developing and validating robust viral NAT protocols. The data and protocols detailed herein demonstrate that method selection profoundly impacts yield, purity, and the subsequent detection of viral targets. Key considerations include the use of enzymatic digestion for enhanced recovery, the application of dual-arm strategies for unbiased HTS, and the adoption of novel reagents that reduce processing time without compromising quality. By applying these standardized evaluation protocols and data presentation guidelines, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly optimize their sample processing pipelines to ensure the highest levels of sensitivity and reliability in viral nucleic acid testing.

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of the COVID-19 pandemic, possesses a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 26–32 kilobases, representing the largest known RNA virus genome [30] [31] [32]. The genomic organization follows a characteristic pattern shared with other beta-coronaviruses, featuring overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) that encode both structural and non-structural proteins essential for viral replication, assembly, and pathogenesis [33] [30]. Understanding this architectural blueprint is fundamental to designing effective nucleic acid testing (NAT) protocols that target diagnostically significant regions.