Virus Isolation in Cell Culture: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth examination of cell culture methodologies for virus isolation.

Virus Isolation in Cell Culture: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth examination of cell culture methodologies for virus isolation. Covering both traditional and modern approaches, it explores foundational principles, practical applications across virology and vaccine development, troubleshooting for common challenges like contamination, and validation techniques for ensuring result accuracy. The content synthesizes current best practices with emerging technologies, addressing critical needs in biopharmaceutical production, diagnostic development, and therapeutic discovery while considering both technical implementation and research quality assurance.

The Evolution and Core Principles of Viral Cell Culture Systems

The evolution of cell culture represents a cornerstone of virology and biomedical research, marking a significant transition from whole-animal models to sophisticated in vitro systems. This progression has been driven by the need for more ethically acceptable, cost-effective, and physiologically relevant models for studying viral pathogenesis, developing vaccines, and screening antiviral compounds. For virus isolation research, the shift has moved from animal inoculation and embryonated eggs to two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures, and more recently, to three-dimensional (3D) models and organ-on-a-chip technologies [1] [2]. These advanced systems aim to closely mimic the in vivo microenvironment, providing more accurate data on viral behavior and host interactions, which is crucial for translational research and drug development [3] [4]. This application note details the key historical milestones, provides comparative data, and outlines practical protocols that trace this transformative journey.

Historical Timeline and Key Transitions

The methodology for virus isolation and culture has undergone profound changes over more than a century. The table below summarizes the major epochs in this development.

Table 1: Historical Epochs in Cell Culture for Virology

| Time Period | Primary Model | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-1950s | Laboratory Animals & Embryonated Eggs [1] [5] | Provided a whole-organism context for infection | High cost, ethical concerns, limited throughput, species-specific differences [6] |

| 1950s–1990s | Traditional 2D Cell Culture (Primary cells & immortalized lines) [1] [5] | Gold standard for virus isolation; cost-effective; convenient [1] [5] | Limited physiological relevance (altered polarity, morphology); does not fully replicate in vivo complexity [4] |

| 2000s–Present | Advanced 3D Cultures & Organ-on-a-Chip Models [3] [4] [7] | Mimics tissue microarchitecture and cell-cell interactions; improved pathophysiological relevance [4] [7] | Technically challenging; higher cost; lack of standardized protocols [8] [4] |

The pivotal turn towards in vitro methods began with Ross G. Harrison's 1907 demonstration of growing frog embryo tissues in clotted lymph [2]. The field was further advanced by Alexis Carrel's work on long-term cell cultivation and the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s to prevent contamination [2]. A landmark achievement was the establishment of the first immortal human cell line, HeLa, in 1951, which revolutionized biomedical research and vaccine development, notably for polio [2]. The late 20th and early 21st centuries have been defined by innovations such as transfection, gene editing, co-culture systems, and 3D culture, collectively enabling more precise and human-relevant virology research [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Culture Models

The transition between models is justified by quantifiable differences in physiological relevance, throughput, and functional output. The following table compares the core characteristics of 2D, 3D, and perfused microfluidic cultures.

Table 2: Quantitative and Functional Comparison of Cell Culture Models

| Characteristic | 2D Static Culture | 3D Spheroid/Organoid Culture | Perfused Organ-on-a-Chip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | Low; altered cell morphology and polarity [4] | High; recapitulates tissue microarchitecture and cell-ECM interactions [4] [7] | Very High; introduces fluid shear stress and mechanical cues [8] |

| Throughput & Cost | High throughput; low cost [8] | Medium throughput; moderate cost [4] | Low throughput; high cost and complexity [8] |

| Drug Screening Concordance | Low (∼8% concordance with clinical trials in animal models highlights 2D limitations) [4] | Improved predictive value for drug efficacy and toxicity [4] [7] | High potential for predicting human pharmacokinetics and efficacy [8] |

| Specific Biomarker Expression | Baseline levels | Enhanced expression in certain contexts | Can induce specific biomarkers >2-fold (e.g., CYP3A4 in Caco-2 cells) [8] |

| Typical Applications in Virology | Routine virus isolation, plaque assays, vaccine production (e.g., FMDV in BHK-21 cells) [9] [5] | Modeling complex viral infections (e.g., respiratory viruses), host-pathogen interactions [3] | Modeling viral entry via vascular flow, systemic infection, and barrier functions (e.g., lung, intestine) [8] [3] |

A meta-analysis of perfused chip models versus static cultures found that while gains in perfusion are modest in 2D, 3D cultures show a slight improvement with flow, suggesting that high-density cell cultures benefit more from perfusion [8]. Furthermore, only specific biomarkers in certain cell types, particularly those from blood vessels, intestine, and liver, react strongly to flow conditions [8].

Established Protocols for Virus Isolation and Culture

Protocol: Traditional Tube Culture for Virus Isolation

This method, the long-standing gold standard, relies on observing virus-induced cytopathic effects (CPE) on monolayer cells [1] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cell Lines: Primary cells (e.g., Rhesus Monkey Kidney - RhMK), human diploid fibroblasts (e.g., MRC-5), or continuous lines (e.g., A549, HEp-2) [1] [5].

- Growth Medium: Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) or Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics [1] [10].

- Maintenance Medium: Serum-free or low-serum version of the growth medium to encourage viral replication over cell proliferation.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Vortex the clinical sample (e.g., swab in transport medium) and centrifuge. Use the supernatant for inoculation [5].

- Inoculation: Aspirate growth medium from a confluent monolayer in a screw-cap tube (or shell vial) and add 0.2-0.3 mL of the processed sample inoculum [5].

- Adsorption: Incubate at 35°C with 5% CO₂ for 60-90 minutes to allow viral adsorption to cells [5].

- Maintenance: Remove the inoculum, wash the monolayer if necessary, and add maintenance medium. Return the culture to the incubator [5].

- CPE Monitoring: Examine the monolayer daily under an inverted microscope for signs of CPE (e.g., cell rounding, syncytia formation, detachment). The time to CPE appearance is virus-dependent (e.g., 1-2 days for HSV; 5-10 days for many enteroviruses; up to 30 days for CMV) [1] [5].

- Virus Identification: Confirm the isolated virus using immunofluorescence assays with virus-specific antibodies [5].

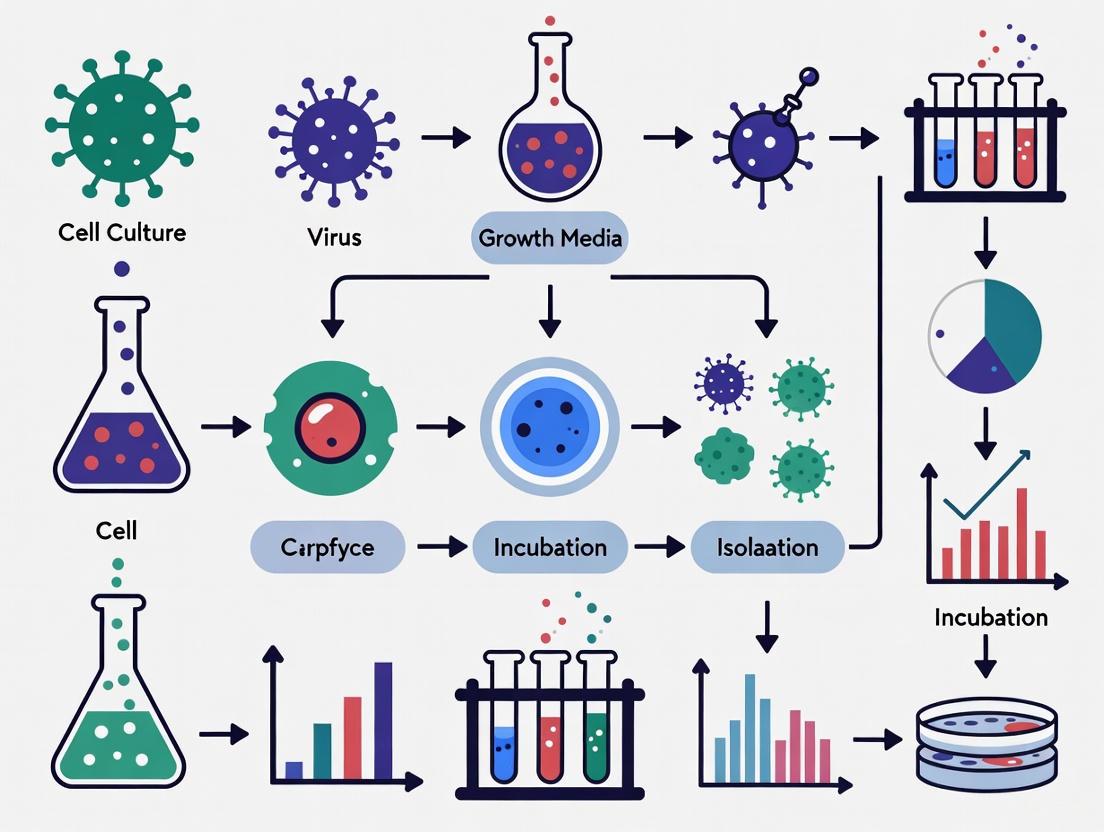

Figure 1: Workflow for traditional virus isolation via cell culture.

Protocol: Modern Rapid Culture using Shell Vials and Co-culture

This method accelerates virus detection by combining centrifugation-enhanced infection and early immunostaining, often using mixed cell lines [1] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Shell Vials: Small vials containing a monolayer on a coverslip.

- Cryopreserved Cells: Ready-to-use monolayers (e.g., MRC-5, A549, R-Mix cells) [5].

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Fluorescein-labeled (FITC) antibodies targeting specific viruses (e.g., influenza, RSV, adenovirus) or cocktail antibodies for multiple targets [5].

- Fixative: Acetone or methanol.

Methodology:

- Inoculation: Add the processed sample to a shell vial with a confluent monolayer.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the vial at low speed (e.g., 700 × g for 30-60 minutes) to enhance viral adsorption via low-speed centrifugation.

- Incubation: Incubate at 35°C with 5% CO₂ for 24-48 hours.

- Staining: Remove the medium, wash, and fix the cells. Add the virus-specific fluorescein-labeled antibody.

- Detection: Examine the fixed monolayer under a fluorescence microscope. Positive samples show characteristic fluorescence, allowing for diagnosis within 1-2 days [5].

Protocol: Generating 3D Spheroids using the Hanging Drop Method

3D spheroids provide a more in vivo-like model for studying virus-host interactions in a tissue-like context [4].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Hanging Drop Plates (HDP): Commercially available plates with access holes for creating hanging drops [4].

- Cell Repellent Surface Plates: Ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates coated with poly-HEMA or commercially treated surfaces to force cell aggregation [4].

- Cell Suspension: Single-cell suspension in standard growth medium, often with reduced serum.

Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Create a single-cell suspension and adjust the cell concentration to the desired density (e.g., 1-5 × 10⁴ cells/mL, depending on spheroid size).

- Dispensing:

- Hanging Drop Method: Pipette droplets (e.g., 20-40 µL) of cell suspension onto the lid of a petri dish. Invert the lid and place it over a dish containing PBS to maintain humidity. Cells aggregate at the bottom of the drop to form a single spheroid [4].

- ULA Plate Method: Seed the cell suspension directly into the wells of an ultra-low attachment plate. The coating prevents adhesion, forcing cells to aggregate into spheroids, often aided by gentle shaking or centrifugation [4].

- Culture: Incubate the plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 24-72 hours to allow spheroid formation.

- Infection: Once mature spheroids form, introduce the virus of interest directly into the medium. Monitor for infection via reporter assays, microscopy, or metabolite analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Modern Cell Culture in Virology

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) Plates | Prevents cell adhesion, forcing aggregation and spheroid formation [4] | Generating uniform tumor spheroids for oncolytic virus studies |

| Chemically Defined Media (CDM) | Serum-free media with defined components; improves reproducibility and reduces contamination risk from animal sera [10] | Culturing CAR-T cells or stem cell-derived organoids for host-pathogen research |

| Hydrogels (e.g., Matrigel, Collagen) | Provides a 3D extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold for embedded 3D culture and organoid growth [4] | Modeling respiratory virus infection in airway epithelial organoids |

| R-Mix Cells | A commercial cocultured cell line (A549 & mink lung) for isolating a broad spectrum of respiratory viruses [5] | Rapid shell vial culture for simultaneous detection of influenza, RSV, and adenovirus |

| Magnetic 3D Bioprinting Kits | Uses magnetic levitation to assemble cells into complex 3D structures for co-culture models [4] [7] | Creating a vascularized tissue model to study viral dissemination |

Signaling Pathways in Viral Entry: FMDV as a Model

The choice of cell culture system is critically influenced by the expression of specific viral entry receptors. Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) provides a clear example of how receptor usage dictates cell line susceptibility and is a key consideration in model selection [9].

Figure 2: FMDV cellular entry pathways via integrin or heparan sulfate receptors.

FMDV typically initiates infection by binding to integrin receptors (αVβ1, αVβ3, αVβ6, αVβ8) via a highly conserved RGD motif located on the VP1 capsid protein [9]. This interaction, characteristic of field viruses, triggers clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The acidic environment of the endosome then promotes capsid disassembly and release of the viral genome into the cytoplasm [9]. In contrast, cell-culture-adapted strains of FMDV often utilize heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans as an alternative receptor. This entry pathway occurs via caveolae-mediated endocytosis [9]. The differential expression of these receptors (e.g., high αVβ6 in epithelial cells) explains the tropism of the virus and underscores why certain cell lines (e.g., BHK-21, primary bovine thyroid cells) are selected for its isolation and propagation [9].

Cell culture serves as a fundamental tool in virology research, providing the necessary living systems for virus isolation, propagation, and pathogenesis studies [11]. These techniques are increasingly favored in pharmacological research and disease modeling due to significant advantages over animal models, including reduced costs, time constraints, and ethical concerns regarding animal use [6]. The intact animal ultimately serves as the source of all cells for culture, which can be obtained from various organs and tissues of embryonic, infant, or adult origin [6]. Cultures of animal cells are systematically classified into three distinct categories: primary cells, cell strains, and continuous cell lines, each possessing unique characteristics that determine their specific applications in virology [6] [12]. Understanding these classifications is essential for researchers investigating viral contaminants such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Ovine Herpesvirus 2 (OvHV-2), which pose significant challenges to research integrity and bioprocess safety [6].

The selection of an appropriate cell culture system directly impacts the success of viral isolation and propagation efforts. Different viruses exhibit specific tissue tropisms and require particular cellular receptors for successful infection and replication [9] [13]. For instance, foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) primarily utilizes integrin receptors found on the surface of susceptible cells, with infection efficiency varying considerably between primary cells and continuous cell lines [9]. Similarly, African swine fever virus (ASFV) isolation has traditionally relied on primary macrophage cultures due to their high sensitivity, though these systems present challenges including low cell yield and contamination risks [14]. This application note provides a comprehensive comparison of primary cells, cell strains, and continuous cell lines, with detailed protocols and implementation frameworks to guide virology researchers in selecting and maintaining appropriate cell culture systems for virus isolation studies.

Classification and Characteristics of Cell Culture Systems

Comparative Analysis of Cell Culture Types

Cell culture systems are broadly categorized into three distinct types based on their origin, lifespan, and characteristics in vitro. The table below summarizes the key features, advantages, and limitations of each category:

Table 1: Characteristics of primary cells, cell strains, and cell lines

| Characteristic | Primary Cells | Cell Strains | Continuous Cell Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Freshly isolated from animal organs or tissues through mechanical or enzymatic methods [12] | Derived from primary cultures that have been subcultured but have not yet undergone transformation [6] | Derived from transformed cells or tumors; often immortalized [12] |

| Lifespan | Finite (usually limited to a few passages) [12] | Finite (capable of 20-80 population doublings before senescence) [6] | Infinite (can be subcultured indefinitely) [12] |

| Growth Characteristics | Exhibit anchorage dependency and contact inhibition [12] | Exhibit anchorage dependency and contact inhibition [6] | May not exhibit anchorage dependency or contact inhibition; can grow in suspension [12] |

| Genetic Profile | Diploid karyotype; genetically similar to original tissue [6] | Diploid karyotype maintained [6] | Aneuploid or heteroploid karyotype; genetically different from original tissue [12] |

| Applications | Virus isolation with high clinical relevance; vaccine production [14] [11] | Research applications requiring more material than primary cells can provide [6] | Large-scale virus propagation; high-throughput screening; basic research [9] [13] |

Cell Culture Systems in Virus Isolation

The selection of an appropriate cell culture system significantly influences the efficiency of virus isolation and propagation. Different viruses exhibit varying tropisms for specific cell types based on the presence of particular surface receptors required for viral entry [9]. For example, foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) primarily utilizes integrin receptors (αVβ1, αVβ3, αVβ6, and αVβ8) found on the surface of susceptible cells, with infection efficiency varying considerably between primary cells and continuous cell lines [9]. Similarly, African swine fever virus (ASFV) isolation has traditionally relied on primary macrophage cultures due to their high sensitivity, though these systems present challenges including low cell yield and contamination risks [14].

Certain continuous cell lines have been specifically engineered or selected for enhanced susceptibility to particular viruses. For instance, the MDCK cell line is widely used for influenza virus propagation, while Vero cells are commonly employed for arbovirus isolation [13] [15]. The H1-HeLa cell line has been developed specifically for human rhinovirus 16 propagation, demonstrating how continuous cell lines can be optimized for specific virological applications [13]. Despite these advantages, primary cells often remain superior for initial virus isolation from clinical specimens due to their preserved physiological receptors and higher sensitivity to wild-type viruses [11] [15].

Table 2: Susceptible cell lines and preferred detection methods for viral contamination

| Virus | Susceptible Cell Lines | Preferred Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) | B95-8 [13] | PCR assays (detects active and latent forms) [6] |

| Ovine Herpesvirus 2 (OvHV-2) | Various animal and insect cell lines [6] | Specific PCR assays; cytopathic effect observation [6] |

| Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus (FMDV) | BHK-21, IB-RS-2, ZZ-R 127, LFBKvB6, primary bovine kidney cells [9] | Virus neutralization tests; plaque assays; cytopathic effect observation [9] |

| African Swine Fever Virus (ASFV) | Primary porcine bone marrow cells, primary macrophage cultures, MA-104 [14] | Hemadsorption assay; real-time PCR; cytopathic effect observation [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Cell Culture in Virus Isolation

Protocol 1: Preparation of Porcine Bone Marrow Primary (PBMP) Cell Culture for ASFV Isolation

Porcine bone marrow primary (PBMP) cell culture offers high sensitivity for African swine fever virus (ASFV) isolation, resulting in high viral yields with minimal contamination risk [14]. This protocol adapts traditional methods to enhance cell yield and reduce contamination, addressing limitations of other primary culture systems such as blood leukocytes and alveolar macrophages.

Materials and Reagents

- Source Animals: Clinically healthy piglets (4-6 weeks old, 8-15 kg) from farms free from ASF, CSF, and other infectious diseases [14]

- Basal Medium: Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) [14]

- Supplements: Fetal Bovine Serum, Gentamicin (40mg/ml), Penicillin G, Streptomycin sulfate [14]

- Digestion Reagent: TrypLE Express Enzyme [14]

- Filter Systems: EZFlow cell strainers [14]

- Culture Vessels: T-25, T-75, and T-225 flasks [14]

Procedure

Necropsy and Bone Marrow Collection:

- Euthanize donor piglet following approved ethical guidelines

- Aseptically collect long bones (femur and tibia) and place in sterile saline solution with antibiotics

- Transfer to biological safety cabinet for all subsequent procedures [14]

Bone Marrow Extraction:

- Remove muscle tissue and cartilage from bone surfaces

- Cut bone ends to expose marrow cavity

- Flush marrow cavity with MEM supplemented with antibiotics using syringe with needle

- Collect marrow plugs in sterile centrifuge tube [14]

Cell Dissociation and Filtration:

- Dissociate bone marrow plugs by repeated pipetting

- Filter cell suspension through EZFlow cell strainer to remove bone fragments and debris

- Centrifuge filtered suspension at 400 × g for 10 minutes

- Resuspend cell pellet in complete growth medium [14]

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed cells at density of 5 × 10^6 cells/cm² in appropriate culture vessels

- Maintain cultures at 37°C in 5% CO₂ humidified incubator

- Replace medium every 2-3 days until confluent monolayer forms (typically 5-7 days) [14]

Quality Control:

- Monitor cultures daily for contamination and cell morphology

- Confirm macrophage phenotype through morphological assessment

- Use only cultures with >95% viability for virus isolation [14]

Applications

PBMP cultures are specifically recommended for ASFV isolation from field samples, even with low virus loads [14]. These cultures support high viral replication and exhibit the characteristic hemadsorption phenomenon, facilitating virus identification.

Protocol 2: Isolation and Culture of Primary Human Corneal Epithelial Cells (HCECs)

Primary human corneal epithelial cells (HCECs) provide a physiologically relevant platform for therapeutic drug testing, offering significant advantages over immortalized cell lines that may exhibit altered gene expression profiles [16]. This protocol standardizes the isolation and culture process to address challenges such as low purity, variable yield, and limited passages.

Materials and Reagents

- Source Tissue: Human corneoscleral buttons from donors (age 18-70 years) with no history of ocular disease [16]

- Basal Medium: Corneal Epithelial Cell Basal Medium [16]

- Growth Supplements: Corneal Epithelial Cell Growth Kit (contains apo-transferrin, epinephrine, Extract P, hydrocortisone hemisuccinate, L-glutamine, rh insulin, CE growth factor) [16]

- Digestion Enzyme: Dispase II solution (15 mg/mL in complete growth medium) [16]

- Coating Substrate: Matrigel matrix solution [16]

- Antibiotics: Penicillin/Streptomycin solution [16]

Procedure

Corneoscleral Button Preparation:

- Transfer corneoscleral button to petri dish using forceps

- Rinse three times with cold HBSS containing 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin

- Carefully trim away remaining scleral tissue to prevent non-corneal epithelial cell contamination [16]

Epithelial Cell Isolation:

- Immerse entire corneoscleral button in 5 mL Dispase II solution (15 mg/mL)

- Incubate at 4°C for 16-24 hours to complete digestion process

- Gently separate epithelial sheet from underlying stroma using forceps

- Dissociate epithelial sheet into single cells by repeated pipetting [16]

Surface Coating:

- Coat culture flasks or plates with diluted Matrigel matrix solution

- Incubate at 37°C for at least 1 hour before cell seeding

- Remove excess coating solution before adding cell suspension [16]

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Seed isolated HCECs onto Matrigel-coated surfaces at appropriate density

- Culture in complete growth medium with specialized supplements

- Maintain at 37°C in 5% CO₂ humidified incubator

- Change medium every 2-3 days [16]

Subculture:

- Detach cells using 0.05% Trypsin-0.02% EDTA when 80-90% confluent

- Neutralize trypsin with Trypsin-neutralizing solution

- Subculture at ratio of 1:3 to 1:4

- Note: Subsequent passages (from passage 3 onward) no longer require Matrigel coating [16]

Functional Validation

- Perform immunofluorescence staining with established markers to identify limbal stem cells and differentiated corneal epithelial cells

- Conduct Ca²⁺ assay to validate functionality by demonstrating intracellular Ca²⁺ release in response to ATP stimulation [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential research reagents for cell culture in virus isolation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Basal Media | Minimum Essential Medium (MEM), Corneal Epithelial Cell Basal Medium [14] [16] | Provide nutritional foundation for cell growth and maintenance |

| Growth Supplements | Fetal Bovine Serum, Corneal Epithelial Cell Growth Kit, L-glutamine [16] [14] | Supply essential growth factors, hormones, and nutrients |

| Dissociation Reagents | TrypLE Express Enzyme, Dispase II, Trypsin-EDTA [14] [16] | Facilitate tissue dissociation and cell detachment during subculturing |

| Antibiotics/Antimycotics | Penicillin/Streptomycin, Gentamicin [16] [14] | Prevent bacterial and fungal contamination |

| Surface Coatings | Matrigel, Laminin, Collagen [16] | Provide extracellular matrix support for cell attachment and growth |

| Cell Separation | EZFlow cell strainers [14] | Remove debris and obtain single-cell suspensions |

| Buffers and Salts | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), D-sorbitol, HBSS [16] [14] | Maintain physiological pH and osmolarity during procedures |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Decision Framework for Cell Culture Selection in Virus Isolation

Viral Infection Pathway in Cell Culture Systems

The strategic selection of appropriate cell culture systems—whether primary cells, cell strains, or continuous cell lines—represents a critical decision point in virology research that directly impacts the success of virus isolation and propagation efforts. Primary cells offer unparalleled physiological relevance and high sensitivity for initial virus isolation from clinical specimens, particularly valuable for fastidious viruses such as African swine fever virus and newly emerging pathogens [14] [15]. Cell strains provide an intermediate solution with extended lifespan while maintaining important biological characteristics, suitable for research applications requiring more material than primary cells can provide [6]. Continuous cell lines deliver consistency, scalability, and convenience for large-scale virus production and high-throughput screening applications, despite potential limitations in physiological relevance due to genetic drift and altered characteristics [9] [13].

As viral diagnostics continue to evolve, cell culture maintains its essential role alongside modern molecular techniques, providing viable virus isolates essential for pathogenesis studies, vaccine development, and antiviral testing [11] [15]. The integration of robust quality control measures, including short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and mycoplasma testing, combined with the implementation of standardized protocols like those presented in this application note, ensures the authenticity and integrity of cell cultures used in virology research [6]. Through careful matching of cell culture systems to specific research objectives, virologists can optimize their experimental outcomes while maintaining the physiological relevance necessary for translating findings into clinical and public health applications.

Essential Laboratory Setup and Safety Considerations for Virology Work

Virology research, particularly work involving virus isolation through cell culture, requires meticulously planned laboratory environments and stringent safety protocols to ensure both scientific integrity and researcher safety. The complex nature of handling infectious agents demands specialized equipment, engineered controls, and comprehensive procedural guidelines. Within the broader context of cell culture methods for virus isolation research, this application note provides detailed guidance on establishing and maintaining a virology laboratory capable of supporting advanced research while containing potential biohazards. These foundational elements enable researchers to effectively isolate and characterize viral pathogens, from common respiratory viruses to emerging threats, using both traditional culture techniques and modern molecular approaches.

Essential Virology Laboratory Equipment

A virology laboratory requires specialized equipment to facilitate the isolation, propagation, and characterization of viral pathogens. The equipment listed in Table 1 represents core components necessary for conducting virology research safely and effectively, with particular emphasis on cell culture applications for virus isolation [17].

Table 1: Essential Equipment for Virology Research

| Equipment Category | Specific Instruments | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Laboratory Tools | Centrifuges, pipettes, pH meters, refrigerators, freezers, microscopes, water baths [17] | General sample preparation, measurement, storage, and initial observation. |

| Specialized Virology Equipment | Biosafety cabinets, autoclaves, vortex mixers, colony counters, ELISA readers [17] | Safe handling of infectious materials, sterilization, sample mixing, and quantitation. |

| Cell Culture & Virus Propagation | CO₂ incubators, shaker water baths, inoculation chambers, adjustable microscope tables [17] | Maintaining cell lines, incubating infections, observing cytopathic effects (CPE). |

| Analytical & Diagnostic Instruments | Spectrometers, mass spectrometry benches, PCR machines, RT-qPCR equipment [17] [18] | Viral load quantification, protein analysis, and molecular detection of viral genetic material. |

Research Reagent Solutions for Virus Isolation

Successful virus isolation in cell culture relies on a suite of essential research reagents and materials. The following table details key components of the "scientist's toolkit" for virological research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Virus Isolation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Virology Research |

|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Serve as host systems for viral replication; selection depends on virus tropism (e.g., Caco-2 and MRC-5 for respiratory viruses) [19]. |

| Growth Media & Sera | Provide essential nutrients to maintain cell viability and support viral propagation in culture. |

| Trypsin/EDTA | Used for detaching adherent cells for subculturing and maintaining cell lines. |

| PCR/RT-qPCR Reagents | Enable detection and quantification of viral nucleic acids from clinical samples or culture supernatants [18]. |

| Primary Antibodies | Used in immunological assays (e.g., immunostaining) to detect viral antigens in infected cells. |

| Transport Media | Preserve viral integrity in clinical specimens (e.g., serum, respiratory samples) during storage and transport [18]. |

Laboratory Design and Safety Framework

Laboratory Zoning and Workflow

Effective virology laboratory design incorporates distinct zones to separate activities by function and risk level, thereby minimizing cross-contamination and enhancing operational efficiency. A well-designed lab should include dedicated areas for: sample storage and processing, handwashing and PPE storage, nucleic acid processing and storage, rapid testing and PCR, biowaste containment, and data analysis [20]. The physical layout should facilitate a unidirectional workflow, moving from clean to dirty areas, with samples processed sequentially through receiving, preparation, analysis, and decontamination stages.

The strategic placement of safety equipment is critical within this workflow. Biosafety cabinets (BSCs) must be located within the cell culture and virus isolation zones to provide primary containment during procedures that may generate aerosols [17] [20]. Emergency equipment including eyewash stations, safety showers, and fire suppression systems should be readily accessible in multiple locations, particularly in high-risk zones [17]. Surface materials also contribute significantly to safety; non-porous, anti-microbial casework and durable epoxy countertops are recommended throughout the laboratory as they are easy to decontaminate and resist bacterial growth [20].

Biosafety Levels and Risk Assessment

Virology work must be conducted at a biosafety level (BSL) appropriate to the specific pathogen being handled, with risk assessments based on factors such as pathogenicity, transmission route, and available treatments [21]. Most diagnostic virology work with agents associated with human disease (e.g., influenza, SARS-CoV-2) requires BSL-2 containment, which includes BSCs, appropriate PPE, and controlled access [22] [21]. More hazardous pathogens require BSL-3 facilities, which incorporate additional engineering controls such as specialized ventilation (negative air pressure) and scaled-up procedural requirements [21].

Core Protocols for Virus Isolation in Cell Culture

Protocol: Cell Culture "Combo" Method for Respiratory Virus Isolation

This protocol outlines a micromethod for inoculating combinations of cell lines ("cell combos") to isolate respiratory viruses that may not be detected by standard molecular techniques, thereby reviving classical virology techniques for contemporary diagnostics [19].

Materials and Reagents

- Cell Lines: Ten selected cell lines combined into five combos of two cell lines each (e.g., Caco-2/MRC-5 combo) [19]

- Growth Media: Cell-type specific media (e.g., MEM, DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum and antibiotics

- Clinical Samples: Respiratory samples (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs, aspirates) found negative by multiplex RT-PCR panels

- Equipment: Biosafety cabinet, CO₂ incubator, inverted microscope, refrigerated centrifuge, pipettes

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the step-by-step workflow for processing samples using the cell combo method for enhanced virus isolation.

Procedure

- Cell Combo Preparation: Culture selected cell line combinations (e.g., Caco-2/MRC-5) in 96-well microplates until they reach 80-90% confluence [19].

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge clinical samples at low speed (2000 × g for 10 minutes) to remove debris and filter through a 0.45 μm membrane.

- Inoculation: Aspirate media from cell combos and inoculate with 50-100 μL of processed sample per well. Include negative controls (media only).

- Incubation & Monitoring: Incubate inoculated cells at 35-37°C with 5% CO₂. Examine cultures daily for 10-14 days using an inverted microscope for appearance of cytopathic effects (CPE) such as cell rounding, syncytia formation, or detachment [19] [6].

- Virus Detection & Confirmation: Harvest supernatant and cells from wells showing CPE. Detect viral genetic material using RT-PCR assays or confirm novel viruses through metagenomic sequencing [19].

- Virus Stock Preparation: Create virus stocks by propagating confirmed isolates in susceptible cell lines, then aliquot and store at -80°C.

Applications and Importance

This method is particularly valuable for investigating undiagnosed respiratory infection outbreaks and detecting emerging viruses that might be missed by targeted molecular assays. The approach successfully isolated 12 herpes simplex or varicella-zoster viruses not detected by respiratory multiplex PCR assays in a proof-of-concept study [19].

Protocol: Viral Isolation from Field-Collected Ticks

This protocol describes methods for isolating and culturing viruses from field-collected ticks, facilitating research into medically significant tick-borne pathogens like Deer tick virus (DTV) and Powassan virus (POWV) [23].

Materials and Reagents

- Ticks: Field-collected ticks, identified to species and life stage

- Cell Lines: Cultured mammalian cells amenable to tick-borne virus replication (e.g., Vero cells)

- Homogenization Buffer: Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or specialized media containing antibiotics and antifungals

- Equipment: Biosafety cabinet, tissue homogenizer, refrigerated centrifuge, CO₂ incubator

Procedure

- Tick Preparation: Surface-sterilize ticks by immersion in 70% ethanol followed by rinsing in sterile PBS.

- Homogenization: Homogenize individual or pooled ticks in cold homogenization buffer using sterile pestles or beads.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the homogenate at high speed (10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C) to remove debris.

- Filtration: Filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm membrane.

- Inoculation: Aspirate media from cultured mammalian cells and inoculate with the filtered supernatant.

- Incubation: Adsorb for 1-2 hours at 37°C, then add fresh maintenance media and incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Monitoring & Harvest: Monitor daily for CPE. Harvest supernatant when CPE is extensive (typically 50-80% of cells affected), then clarify by centrifugation and store aliquots at -80°C.

Safety Protocols and Best Practices

Comprehensive Safety Equipment

Virology laboratories must be equipped with multiple layers of safety equipment to protect personnel and the environment. Essential safety equipment includes [17] [20]:

- Primary Containment: Biosafety cabinets (Class II or III) for all procedures with infectious materials

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Lab coats, gloves, eye protection, and respiratory protection as needed

- Decontamination Equipment: Autoclaves for sterilizing infectious waste before disposal

- Emergency Equipment: Eyewash stations, safety showers, and fire suppression systems

Administrative Controls and Training

Robust administrative controls form the foundation of laboratory safety. All laboratory personnel must receive comprehensive training in [22]:

- Biosafety Protocols: Specific procedures for handling virus and virus-infected cells

- PPE Usage: Proper selection, use, and removal of personal protective equipment

- Emergency Procedures: Response to spills, exposures, and other incidents

- Waste Management: Proper segregation and decontamination of biological waste

Principal investigators are responsible for ensuring all laboratory members read and comprehend the laboratory biosafety protocol and should provide clear documentation of safety procedures, vacation/sick leave policies, and expectations regarding work hours to promote a healthy work-life balance [22].

Establishing a virology laboratory for cell culture-based virus isolation requires meticulous planning of both physical infrastructure and operational protocols. The essential components include appropriate biosafety containment, specialized equipment for virus propagation and detection, and comprehensive safety systems. The protocols outlined herein, particularly the cell culture "combo" method for respiratory virus isolation, provide powerful tools for detecting known and emerging viral pathogens that might evade standard molecular detection methods. By integrating these specialized techniques with rigorous safety practices, researchers can create a productive laboratory environment that facilitates critical virology research while ensuring the safety of personnel and the community.

Cytopathic effect (CPE) refers to the structural changes in host cells that are caused by viral invasion [24]. When a virus induces these morphological changes, it is termed cytopathogenic [24]. The observation of CPE remains a cornerstone technique in virology, serving as a critical diagnostic tool for identifying and characterizing viral infections in cell culture [24]. For researchers investigating virus isolation, CPE provides visual evidence of viral presence and replication, offering insights into viral pathogenicity and host-cell interactions.

The underlying mechanisms of CPE involve viral hijacking of cellular machinery, often culminating in cell death. This can occur through direct lysis (dissolution) of the host cell or when the cell dies without lysis due to its inability to reproduce [24]. These changes are a necessary consequence of efficient virus replication, occurring at the expense of the host cell's viability [24]. The progression of these changes is most readily observed in cell culture, where infection can be synchronized and cells can be frequently monitored [25].

Types and Classifications of CPE

Cytopathic effects manifest in various forms, each providing characteristic clues about the infecting virus. Skilled virologists can distinguish these types even in unstained, living cultures [26]. The major CPE categories are detailed in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Common Types of Cytopathic Effects (CPE) and Associated Viruses

| CPE Type | Morphological Description | Characteristic Viruses |

|---|---|---|

| Total Destruction | Complete destruction and detachment of the host cell monolayer within days [24]. | Enteroviruses [24] [27] |

| Subtotal Destruction | Partial detachment of the cell monolayer; some cells remain attached [24]. | Togaviruses, some Picornaviruses, some Paramyxoviruses [24] [27] |

| Focal Degeneration | Localized areas of infection (foci) where cells become rounded, enlarged, and refractile [24]. | Herpesviruses, Poxviruses [24] [27] |

| Swelling and Clumping | Significant cell swelling followed by clumping into clusters before detachment [24]. | Adenoviruses [24] [27] |

| Syncytium Formation | Fusion of plasma membranes of multiple cells, creating large cells with multiple nuclei (polykaryons) [24] [26]. | Paramyxoviruses, Herpesviruses, some Coronaviruses [24] [26] |

| Foamy Degeneration | Formation of large or numerous cytoplasmic vacuoles (vacuolization) [24]. | Certain Retroviruses, Flaviviruses, Paramyxoviruses [24] [27] |

| Inclusion Bodies | Abnormal insoluble structures within the nucleus or cytoplasm; areas of viral synthesis or assembly [24] [26]. | Rabies virus (cytoplasmic), Herpesviruses (nuclear), Adenoviruses (nuclear) [24] [26] |

The rate at which CPE appears is also a diagnostically useful characteristic. A virus is considered "slow" if CPE appears after 4 to 5 days in vitro at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI), and "rapid" if it appears after 1 to 2 days under the same conditions [24].

Mechanisms of CPE Induction

The structural changes observed as CPE are the visual manifestation of profound biochemical disruptions within the infected cell. Several key mechanisms contribute to this damage.

Shutdown of Host Cell Synthesis

Many cytocidal viruses code for proteins that actively shut down host cell protein synthesis, an event incompatible with long-term cell survival [26]. This shutdown is particularly rapid and severe in infections by picornaviruses, some poxviruses, and herpesviruses [26]. Cellular RNA and DNA synthesis are typically affected as a secondary consequence.

Direct Cytopathic Effects of Viral Proteins

While viruses do not produce classic toxins, viral components can be directly toxic to the cell. For instance, viral capsid proteins, such as the adenovirus penton and fiber proteins, can be a principal cause of CPE when present in high concentrations [26]. The accumulation of viral proteins late in the replication cycle is a common pathway leading to cell damage.

Membrane Alteration and Cell Fusion

Many viruses insert viral proteins into the host cell's plasma membrane, which can alter its permeability and lead to osmotic swelling [26]. Notably, viruses like paramyxoviruses and herpesviruses produce fusion proteins that cause the plasma membranes of infected cells to fuse with adjacent uninfected cells, forming syncytia [24] [26]. This allows the virus to spread directly from cell to cell, evading host antibodies [24].

Diagram 1: Key mechanisms through which viruses induce cytopathic effects.

CPE-Based Assays for Antiviral Research

The quantifiable nature of virus-induced cell death makes CPE-based assays powerful tools for antiviral drug discovery and virology research. These assays measure viral infectivity directly by assessing the potency of compounds in inhibiting the replication of infectious viruses [28].

The CPE Inhibition Assay

This assay is suitable for high-throughput screening in a 96-well plate format [28]. It typically involves infecting a cell monolayer with a virus and then measuring cell viability in the presence or absence of antiviral compounds. A common readout involves measuring cellular ATP levels, which are present in viable cells and depleted upon cell death. A reduction in luminescence signal indicates viral-induced CPE, enabling the quantitation of antiviral efficacy [29].

Plaque Assay

The plaque assay is a more labor-intensive method that serves as a secondary assay to confirm antiviral activity [28]. It involves infecting a cell monolayer with serial dilutions of a virus sample. A semi-solid overlay medium is added to prevent uncontrolled viral spread, ensuring that infection is limited to neighboring cells. Each infectious viral particle produces a clear zone of lysed cells or CPE, known as a "plaque," which can be counted to quantify infectious viral titer [28].

Determining TCID₅₀ (Tissue Culture Infective Dose)

The TCID₅₀ is the virus dilution that reduces measured cell viability by 50% [29]. This value is critical for standardizing viral inoculums in subsequent experiments, such as potency testing of antiviral agents. To determine TCID₅₀, serial dilutions of a virus stock are added to target cells. After a specified incubation period, cell viability is measured, and the results are plotted to find the dilution that causes 50% cell death [29].

Diagram 2: Generalized workflow for a CPE-based antiviral screening assay.

Table 2: Optimized Assay Conditions for Human Coronaviruses in CPE and Plaque Assays

| Virus | Assay | Cell Line | Incubation Temperature (°C) | Incubation Time (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCoV-OC43 | CPE | RD | 33 | 4.5 |

| HCoV-OC43 | Plaque | RD | 33 | 4.5 |

| HCoV-229E | CPE | MRC-5 | 33 | 5.5 |

| HCoV-229E | Plaque | RD | 33 | 5.5 |

| HCoV-NL63 | CPE | Vero E6 | 37 | 4 |

| HCoV-NL63 | Plaque | Vero E6 | 37 | 4 |

Source: Adapted from [28]

Application Note: Quantitative CPE Measurement Using a Luminescence Assay

Background and Principle

Traditional microscopic assessment of CPE is qualitative and time-consuming. The Viral ToxGlo Assay provides a simple, mix-and-read format that quantifies cell viability based on the measurement of cellular ATP, which is present in viable cells and depleted upon viral-induced cell death [29]. Depletion of ATP leads to a reduction in luminescence signal, enabling robust quantitation of viral-induced CPE [29].

Key Advantages

- Speed: Results are obtained just 10 minutes after reagent addition [29].

- Sensitivity: Luminescence readout provides high sensitivity suitable for screening [29].

- Quantitative: Generates numerical data (RLU) for accurate calculation of values like TCID₅₀ and EC₅₀, surpassing qualitative visual assessment [29].

- Reproducibility: The assay demonstrates excellent reproducibility [28].

Protocol: Measuring Antiviral Potency (EC₅₀)

This protocol outlines the steps to determine the concentration of an antiviral compound that provides 50% protection from viral CPE (EC₅₀).

- Cell Seeding: Plate host cells (e.g., MDCK or MRC-5) at a density of 10,000 cells per well in a 96-well white microplate with clear bottoms. Include no-cell control wells. Allow cells to attach and grow overnight at 37°C and 5% CO₂ [29].

- Compound and Virus Addition:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the antiviral compound (e.g., Ribavirin, Remdesivir) in culture media.

- Add diluted compound to the cell plate.

- Add a pre-determined dilution of virus stock that will produce optimal CPE to the test wells. To assess compound cytotoxicity, add the same dilution series to a separate set of wells without virus [29].

- Incubation: Incubate the treated cell plates at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 33°C or 37°C) and 5% CO₂ for the virus-specific duration (e.g., 3-6 days) [29].

- Viability Measurement:

- Add the Viral ToxGlo ATP detection reagent to all assay wells.

- Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to allow cell lysis and signal development.

- Seal the plate and read the luminescent signal on a compatible microplate reader [29].

- Data Analysis:

- Plot results as Relative Light Units (RLU) versus compound concentration using a 4-parameter logistic curve fit in analysis software.

- The EC₅₀ value is the compound concentration that rescues 50% of the virus-induced CPE. The CC₅₀ (cytotoxic concentration 50) can be determined from the wells containing compound but no virus [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for CPE-Based Assays

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Viral ToxGlo Assay Kit | Quantitative measurement of cell viability via ATP-dependent luminescence; used to quantify CPE [29]. | High-throughput screening of antiviral compounds against HCoV-229E and Influenza A (H1N1) [29]. |

| Cell Lines: Vero E6, MRC-5, RD, MDCK | Mammalian cell lines that support the replication of specific viruses and display characteristic CPE. | Vero E6 for HCoV-NL63; MRC-5 for HCoV-229E; MDCK for Influenza A virus [29] [28]. |

| Remdesivir | Nucleoside analog antiviral drug; used as a positive control in antiviral assays [28]. | Calibration of CPE and plaque assays for human coronaviruses; EC₅₀ determination [29] [28]. |

| Ribavirin | Broad-spectrum antiviral nucleoside analog; used as a positive control [29]. | Measuring protection against CPE induced by viruses like Influenza A (H1N1) [29]. |

| 96-well & 6-well Tissue Culture Plates | Platforms for cell culture; 96-well for high-throughput CPE assays, 6-well for plaque assays [28]. | CPE assay in 96-well format; plaque assay for titer determination or confirmatory testing in 6-well format [28]. |

| SpectraMax iD5 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader | Instrument for sensitive detection of luminescence signals from viability assay kits. | Reading luminescence in the Viral ToxGlo Assay [29]. |

The observation and quantification of cytopathic effects remain fundamental techniques in diagnostic virology and antiviral research. The ability to visually identify viral infection through characteristic morphological changes in cell culture provides a powerful, direct method for virus isolation and identification. Furthermore, the translation of this visual readout into robust, quantitative assays has cemented the role of CPE in modern drug discovery pipelines. By utilizing the protocols and applications detailed in this document, researchers can effectively leverage CPE to advance our understanding of viral pathogenesis and develop novel therapeutic agents to combat emerging viral threats.

Virus isolation in cell culture remains a foundational technique in clinical virology, vital for pathogen discovery, vaccine development, and antiviral drug evaluation. Despite advancements in molecular diagnostics, the ability to isolate and propagate viruses in susceptible cell lines provides an irreplaceable tool for obtaining infectious viral stocks, conducting phenotypic characterization, and detecting unknown pathogens. The selection of appropriate cell lines is paramount, as viral tropism varies significantly, and no single cell line supports the growth of all viruses. This application note details the specific uses and performance characteristics of four critical cell lines—RhMK, MRC-5, HEp-2, and A549—in the context of a broader thesis on cell culture methods for virus isolation. We provide a consolidated reference of quantitative performance data and detailed protocols to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in optimizing their viral diagnostic and research workflows.

Comparative Susceptibility of Key Cell Lines

The effectiveness of a cell line for virus isolation is measured by its susceptibility, which dictates both the range of viruses it can detect and the efficiency of isolation. The following table summarizes the core applications and performance metrics for the four key cell lines, based on published studies.

Table 1: Viral Susceptibility and Performance of Key Cell Lines

| Cell Line | Cell Type / Origin | Primary Viral Applications | Isolation Performance and Comparative Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| RhMK (Rhesus Monkey Kidney) | Primary, epithelial | Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), Influenza, Parainfluenza | RSV: CPE in 50% of cultures in 5 days, 90% in 7 days [30]. Influenza/Parainfluenza: Broadly used, but may be outperformed by other lines like MDCK or CACO-2 for influenza [31]. |

| MRC-5 | Human diploid lung fibroblast | Influenza Virus, RSV, Cytomegalovirus, Adenovirus (less susceptible) | Influenza: 18% isolation rate, comparable to MDCK cells (15%) when treated with trypsin [32]. RSV: Used in combination with RhMK and HEp-2 for maximal yield; slower CPE development than RhMK [30]. HSV: 73.6% isolation rate, less sensitive than A549 (92.5%) [33]. |

| HEp-2 | Human epithelial carcinoma | Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | RSV: 48% isolation rate, considered a benchmark for HRSV isolation [34]. Often used in combination with other cells (e.g., RhMK, MRC-5) to improve overall viral detection [30]. |

| A549 | Human lung carcinoma | Adenovirus, Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), Respiratory Viruses | Adenovirus: 93.8% isolation rate, superior to HEK (87.0%) and CMK (47.5%) cells [33]. HSV: 92.5% isolation rate, comparable to Vero (89.0%) and superior to MRC-5 (73.6%) [33]. Can be engineered for susceptibility to other viruses (e.g., HCoV-229E) [35]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Virus Isolation

Protocol 1: Isolation of Respiratory Viruses using a Combination Cell Culture System

This protocol, adapted from published methods, maximizes the recovery of common respiratory viruses like RSV and influenza by utilizing the complementary tropisms of multiple cell lines [30] [32].

Application: Isolation of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), Influenza Virus, and other respiratory pathogens. Key Cell Lines: RhMK, MRC-5, HEp-2 [30] [32].

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Lines: Confluent monolayers of RhMK, MRC-5, and HEp-2 cells in appropriate tissue culture flasks or shell vials.

- Specimen: Nasopharyngeal swab or aspirate in viral transport media (e.g., M4).

- Growth Media: Cell line-specific maintenance media (e.g., MEM, DMEM) supplemented with antibiotics (Penicillin/Streptomycin) and antifungals (Amphotericin B).

- Trypsin: For MRC-5 cells used in influenza isolation, add TPCK-trypsin to a final concentration of 1-2 µg/mL [32].

- Fixation and Staining Reagents: Acetone, virus-specific monoclonal antibodies, and fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies.

Procedure:

- Specimen Preparation: Vortex the clinical specimen in transport media and clarify by low-speed centrifugation (~500 x g for 10 minutes).

- Inoculation: Aseptically remove growth media from the cell cultures and inoculate each cell line with 0.2-0.5 mL of the supernatant from the prepared specimen. Include negative control cultures inoculated with maintenance media only.

- Adsorption: Incubate the inoculated cultures at 33-35°C for 60-90 minutes to allow for viral adsorption. Rock the cultures every 15-20 minutes.

- Maintenance: After adsorption, add maintenance media to the cultures. For MRC-5 cells used for influenza, ensure the maintenance media contains trypsin [32]. Incubate all cultures at 33-35°C and observe daily for Cytopathic Effect (CPE).

- Observation and Monitoring:

- RhMK cells: Examine daily for RSV-specific CPE (e.g., syncytia formation). According to studies, 50% of positive RSV cultures show CPE by day 5 and 90% by day 7 [30].

- MRC-5 and HEp-2 cells: Monitor for cell rounding and degeneration. CPE development in MRC-5 cells may be slower than in RhMK for RSV [30].

- Confirmation: Upon observation of CPE or at a predetermined endpoint (e.g., 7-10 days post-inoculation), confirm the presence of virus by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or PCR. For IFA, scrape the cell monolayer, spot onto slides, fix with acetone, and stain with virus-specific antibodies.

Protocol 2: Optimized Isolation of Adenovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus using A549 Cells

The A549 cell line demonstrates high susceptibility to adenovirus and HSV, making it a superior choice for isolating these pathogens [33].

Application: Isolation of Adenovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV). Key Cell Lines: A549.

Materials and Reagents:

- Cell Line: A549 cells at a low passage number (passage <120 recommended to maintain optimal susceptibility) [33].

- Specimen: Throat swab (for adenovirus) or lesion swab (for HSV) in viral transport media.

- Growth Media: DMEM or EMEM supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS, 2-10%), L-glutamine, and antibiotics.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Use A549 cells that are 80-100% confluent. Avoid using cells at high passage numbers (>120) as sensitivity to adenovirus may decline [33].

- Inoculation: Follow the specimen preparation and adsorption steps as described in Protocol 1.

- Incubation and Monitoring: Incubate inoculated A549 cultures at 36°C and observe daily for CPE.

- Confirmation: Confirm the viral identity by IFA, as described in Protocol 1. The high susceptibility of A549 cells often leads to rapid and extensive CPE, facilitating easy detection.

Visualizing the Virus Isolation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting the appropriate cell line based on the suspected viral pathogen, as derived from the protocols and data above.

Diagram Title: Cell Line Selection for Virus Isolation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogues the essential materials and reagents required to establish a robust viral culture system using the featured cell lines.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Virus Isolation in Cell Culture

| Reagent/Cell Line | Function / Application | Specific Notes and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary RhMK Cells | Isolation of RSV, influenza, and parainfluenza viruses. | High susceptibility to RSV; CPE develops rapidly. Limited lifespan and potential for endogenous viral contaminants [30]. |

| MRC-5 Cell Strain | Isolation of influenza, RSV, and cytomegalovirus. | Human diploid fibroblast; reliable and standardized. Requires trypsin supplementation in media for optimal influenza isolation [30] [32]. |

| HEp-2 Cell Line | Benchmark cell line for isolation of Human RSV (HRSV). | Provides consistent results for HRSV. Often used in combination with other cell lines to maximize detection sensitivity [34]. |

| A549 Cell Line | Highly sensitive isolation of adenovirus and HSV. | Efficient and economical alternative. Monitor passage number; sensitivity may decrease after passage 120 [33]. |

| Viral Transport Media (e.g., M4) | Preserves viral viability during specimen transport. | Essential for maintaining sample integrity from collection to laboratory inoculation [31]. |

| TPCK-Trypsin | Cleaves influenza hemagglutinin, enabling multi-cycle replication. | Critical supplement for culturing influenza virus in MRC-5 and other non-enterocytic cells [32]. |

| Virus-Specific Monoclonal Antibodies | Confirmation and identification of isolated viruses via IFA. | Allows for rapid, specific typing of the virus causing CPE in the culture [34]. |

Practical Protocols: Traditional and Advanced Techniques for Virus Cultivation

Virus isolation in cell culture remains a foundational technique in clinical virology and viral research, providing a means to detect, amplify, and identify infectious viral pathogens. Within this domain, three methodological approaches have evolved to address differing needs for throughput, speed, and scalability: conventional tube cultures, shell vial cultures, and microtiter plate-based techniques. These methods serve as critical tools for diagnosing infections, conducting epidemiological studies, and supporting drug and vaccine development. Despite the emergence of molecular detection methods, virus isolation retains irreplaceable value for confirming active infection, obtaining viral isolates for characterization, and evaluating antiviral efficacy. This application note details the protocols, applications, and performance characteristics of these three standard isolation methods within the broader context of cell culture methodologies for virus research.

Methodological Principles and Comparative Analysis

Technical Foundations

Conventional Tube Cultures (TC): This traditional method involves inoculating clinical specimens onto cell monolayers in culture tubes, which are then incubated for days to weeks and monitored periodically for cytopathic effect (CPE). It is considered a "gold standard" for its ability to detect a wide spectrum of viruses but is limited by long turnaround times [36] [37].

Shell Vial Cultures (SV): Developed to accelerate viral detection, this centrifugation-enhanced assay uses small vials containing a coverslip with a cell monolayer. Specimens are centrifuged onto the monolayer to enhance viral adsorption, followed by incubation for 16-48 hours and subsequent immunostaining for early viral antigens. This method significantly reduces detection time compared to conventional tube cultures [36] [37] [38].

Microtiter Plate-Based Isolation: This high-throughput approach adapts virus isolation to 96-well plate formats, allowing parallel processing of numerous samples. After incubation, viral presence is typically detected using immunostaining assays such as immunoperoxidase monolayer assay (IPMA) or monolayer enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (M-ELISA) [39] [40].

Performance Comparison of Isolation Methods

The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of these methods for detecting various viruses across published studies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Virus Isolation Methods

| Virus Detected | Method | Detection Time | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) | Shell Vial (MRC-5 cells) | 16 hours | 100 | 100 | Detected 124 positives vs. 88 by TC; more sensitive than TC (9-day average) [36] |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | Shell Vial (CoHLM cells) | 48 hours | 94.1 (160/170 strains) | N/R | Detected 160 of 170 strains vs. 167 by TC (mean 6 days) [37] |

| Various Respiratory Viruses* | Shell Vial | 48 hours | 95.2 | N/R | Overall detection of 160/170 isolates; TC detected 167/170 [37] |

| Influenza A & B | Shell Vial | 48 hours | 100 (18/18, 4/5) | N/R | Detected all 18 Flu A and 4 of 5 Flu B isolates [38] |

| Adenovirus | Shell Vial | 48 hours | 47.6 (10/21) | N/R | Shell vials were ineffective for adenovirus compared to TC [38] |

| Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) | Microtiter IPMA/M-ELISA | 4 days | 85 (100 for PI^) | 100 | Relative to standard VI; required only 4 days of incubation [39] |

*Respiratory viruses include RSV, influenza A and B, parainfluenza 1-3, and adenovirus. ^PI: Persistently infected cattle.

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the procedural workflows for the three virus isolation methods and a decision pathway for selecting the appropriate technique:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Shell Vial Culture for Respiratory Viruses

Principle: Centrifugation-enhanced infection of mixed cell monolayers on coverslips enables rapid detection of multiple respiratory viruses through immunofluorescence staining within 48 hours [37].

Materials:

- Shell vials (1-dram, ~3.7 ml) with 12-mm coverslips

- Cell lines: HEp-2, LLC-MK2, and MDCK

- Modified Eagle Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)

- Clinical specimens (nasal wash, nasopharyngeal aspirates)

- Virus-specific monoclonal antibodies (e.g., Respiratory Viral Screen IFA)

- Fluorescence microscope

Procedure:

- Cell Monolayer Preparation:

- Prepare separate suspensions of HEp-2, LLC-MK2, and MDCK cells at 150,000 cells/ml.

- Create a mixed cell suspension containing 50,000 cells/ml of each cell type.

- Add 1 ml of the mixed cell suspension to each shell vial containing a coverslip.

- Incubate vials at 37°C for 24 hours to form confluent monolayers.

Specimen Processing:

- Sonicate nasal wash specimens for 1 minute.

- Centrifuge at 500 × g for 5 minutes to obtain cell-free supernatant.

Inoculation and Centrifugation:

- Inoculate 0.2 ml of specimen supernatant onto each of two shell vials.

- Centrifuge vials at 3,500 × g for 15 minutes at 25°C.

- Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour for adsorption.

Maintenance and Incubation:

- Discard supernatant and add 1 ml of maintenance MEM with 1% FBS and 0.2 μg/ml trypsin.

- Incubate vials at 37°C with continuous shaking for 48 hours.

Virus Detection and Identification:

- After 48 hours, remove one vial and fix the coverslip monolayer with cold (-20°C) acetone.

- Stain with pooled monoclonal antibodies against respiratory viruses (RSV, adenovirus, influenza A/B, parainfluenza 1-3).

- If fluorescent cells are observed, fix and stain the second vial with virus-specific monoclonal antibodies for final identification.

- Examine under fluorescence microscope at ×250 magnification.

Protocol 2: Microtiter Plate Virus Isolation with Immunostaining

Principle: Cell culture in 96-well microtiter plates enables high-throughput virus isolation with detection via immunoperoxidase or ELISA-based methods, ideal for screening large sample numbers [39].

Materials:

- 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates

- Appropriate cell line (e.g., bovine cells for BVDV)

- Growth and maintenance media

- Serum samples for testing

- Virus-specific monoclonal antibodies

- Species-specific peroxidase conjugate

- Enzyme substrate (e.g., AEC for IPMA, ABTS for M-ELISA)

- Plate reader (for M-ELISA)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding:

- Prepare cell suspension at appropriate concentration (e.g., 1×10^5 cells/ml).

- Dispense 100 μl/well into 96-well microtiter plates.

- Incubate at 37°C with 5% CO₂ until confluent monolayers form (24-48 hours).

Sample Inoculation:

- Remove growth medium from wells.

- Inoculate test serum samples (10-20 μl/well) in duplicate or triplicate.

- Include appropriate positive and negative controls.

- Incubate plates at 37°C for 1 hour for adsorption.

Maintenance and Incubation:

- Add maintenance medium to wells.

- Incubate plates at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 4 days.

Immunoperoxidase Monolayer Assay (IPMA):

- Remove medium and wash cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Fix cells with 20-30% acetone for 10 minutes.

- Add virus-specific monoclonal antibody and incubate for 30-60 minutes.

- Wash and add species-specific peroxidase conjugate for 30-60 minutes.

- Add enzyme substrate (AEC) and incubate until color develops.

- Examine for red intracellular precipitate under microscope.

Monolayer ELISA (M-ELISA) Alternative:

- After fixation, follow similar antibody binding steps as IPMA.

- Use substrate that produces soluble colored product (e.g., ABTS).

- Measure optical density with plate reader for objective results.

Protocol 3: Conventional Tube Culture for Virus Isolation

Principle: Inoculation of specimens onto cell monolayers in culture tubes with extended incubation allows detection of a wide range of viruses through observation of cytopathic effects, serving as a reference standard [36] [41].

Materials:

- Cell culture tubes with appropriate cell lines (e.g., MRC-5, WI38, rhesus monkey kidney)

- Maintenance medium (Eagle's minimum essential medium)

- Clinical specimens (urine, blood, tissue, respiratory secretions)

- Inverted microscope

Procedure:

- Cell Monolayer Preparation:

- Select appropriate cell lines based on target viruses.

- Ensure confluent, healthy monolayers in culture tubes before inoculation.

Specimen Inoculation:

- Inoculate 4 drops of antibiotic-treated specimen onto cell monolayer.

- Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour to allow viral adsorption.

Maintenance and Observation:

- Add 1.5 ml of maintenance medium to each tube.

- Incubate tubes at 37°C and examine daily for cytopathic effect (CPE) using an inverted microscope.

- Continue observation for up to 14 days, depending on suspected virus.

Hemadsorption (for certain viruses):

- For tubes without CPE at days 5-10, perform hemadsorption with guinea pig erythrocytes.

- Scrape cells and test with specific immunofluorescence if hemadsorption positive.

Virus Identification:

- Once CPE is observed, identify virus using type-specific immunofluorescence.

- Subculture to fresh tubes for virus propagation if needed.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Virus Isolation Methods

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Function/Purpose | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRC-5 Cells | Virus Isolation | Human diploid lung fibroblast; sensitive to many human viruses | CMV detection [36], general viral diagnosis |

| HEp-2 Cells | Respiratory Virus Isolation | Human laryngeal carcinoma; sensitive to RSV and adenoviruses | Component of CoHLM mixed cell system [37] |

| LLC-MK2 Cells | Respiratory Virus Isolation | Rhesus monkey kidney; sensitive to influenza and parainfluenza | Component of CoHLM mixed cell system [37] |

| MDCK Cells | Influenza Isolation | Canine kidney; optimal for influenza A and B propagation | Component of CoHLM mixed cell system [37] |

| Virus-Specific Monoclonal Antibodies | Viral Detection & Identification | Immunological recognition of specific viral antigens | Early antigen detection in shell vials [36] |

| Pooled Monoclonal Antibodies | Viral Screening | Simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory viruses | Respiratory Viral Screen IFA [37] |

| Fluorescein-Labelled Conjugates | Immunofluorescence | Fluorescent detection of antibody-bound viral antigens | Shell vial staining [37] [38] |

| Peroxidase Conjugates | Immunostaining | Enzymatic detection for colorimetric visualization | IPMA and M-ELISA [39] |

Standard virus isolation methods including tube cultures, shell vial assays, and microtiter plate techniques provide a hierarchy of options balancing throughput, speed, and detection breadth. Conventional tube culture remains the comprehensive reference method despite its extended timeline. Shell vial cultures with centrifugation-enhancement offer an optimal balance of speed (24-48 hours) and sensitivity for many clinical applications, particularly for cytomegalovirus and respiratory viruses like RSV and influenza. Microtiter plate-based systems excel in high-throughput scenarios requiring standardized processing of large sample numbers. Method selection depends on specific application requirements: tube cultures for broad detection where time is secondary, shell vials for rapid clinical diagnosis, and microtiter methods for large-scale screening programs. Together, these established isolation methods continue to provide indispensable tools for both clinical virology and pharmaceutical research, maintaining relevance alongside molecular techniques by delivering biologically active virus isolates essential for pathogenesis studies, antiviral development, and vaccine production.

Optimizing Sample Collection, Processing, and Inoculation Techniques

Within the framework of virus isolation research, the pathway to successful cell culture begins long before a specimen enters the biosafety cabinet. The pre-analytical phase—encompassing sample collection, processing, and the preparation of inoculum—is a critical determinant of experimental success. Errors introduced during these initial steps can lead to false negatives, compromised cell cultures, or a complete failure to isolate the viable virus, thereby invalidating subsequent research efforts. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols designed to standardize and optimize these foundational techniques. By implementing these evidence-based procedures, researchers can enhance the sensitivity, reliability, and reproducibility of their viral isolation studies, ensuring that high-quality data flows from robust methodological beginnings.

Optimizing Sample Collection and Transport

The integrity of viral isolation research is fundamentally dependent on the initial collection and stabilization of specimens. The choice of tools, media, and handling conditions directly influences the recovery of viable viral particles.

Selection of Sample Collection Devices

The physical properties of the collection swab significantly impact the release of viral material into transport media. The following table summarizes key findings from a comparative study on sample collection devices:

Table 1: Comparison of Sample Collection Device Efficacy for Virus Recovery

| Device Type | Viral RNA Detection Rate (%) | Geometric Mean Titer (Log10 EID50 Equivalents per 25 cm²) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-moistened Cotton Gauze | 100% | 3.2 | Superior sample absorption and elution; optimal for environmental surface sampling [42]. |

| Foam Swab | 95% | 2.8 | Effective recovery; often used in clinical and veterinary settings [42] [43]. |

| Flocked Nylon Swab | Not Specified | Not Specified | Consistently performs well with transport media; superior sample release due to perpendicular fibers [43]. |

| Dry Cotton Gauze | 93% | 2.6 | Lower recovery and detection rates compared to pre-moistened and foam alternatives [42]. |

| Non-flocked Dacron Swab | Not Specified | Not Specified | Inferior recovery compared to flocked and foam swabs [43]. |

Choice of Transport Media and Conditions

The chemical composition and volume of the transport medium are crucial for preserving viral viability during transit.

- Media Formulation: Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth has been demonstrated to be superior to Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) for maintaining virus stability, leading to a higher number of positive virus isolations [43]. The medium must contain antibiotics and protein (e.g., albumin or serum) to prevent microbial overgrowth and stabilize viral particles.

- Media Volume: While 2-3.5 mL is common, a larger volume (e.g., 3.5 mL) may improve detection sensitivity for samples with low viral load, as it demonstrates a trend towards more positive results at later time points post-infection [43].

- Wet vs. Dry Transport: Transporting swabs in media is consistently better for virus recovery and detection than transporting them dry. Leaving the swab in the media vial during transport is recommended, as removing it does not improve recovery and may marginally decrease it [43].

Timing and Specimen Handling

- Timing of Collection: Specimens should be collected as early as possible following the onset of clinical signs, ideally within the first week, when viral shedding is typically highest [11].

- Temperature Control: Specimens must be refrigerated immediately after collection and transported to the laboratory on wet ice or cold packs as quickly as possible, preferably within 24 hours [11]. For delays exceeding 2-3 days, freezing at -70°C is preferable to -20°C to minimize loss of viability [11]. Note that for molecular detection from wastewater, storage at 4°C has been shown to enhance SARS-CoV-2 detection compared to -20°C [44].

Figure 1: Optimized Workflow for Viral Sample Collection and Transport

Sample Processing and Nucleic Acid Isolation

Efficient release and purification of nucleic acids are prerequisites for sensitive molecular detection and characterization. The following protocol, adapted for a variety of sample types, ensures high-quality extracts.

CTAB-Based Protocol for Complex Samples

This method is particularly effective for complex or difficult samples, such as plant tissues stored in silica gel, and produces nucleic acids of high quality suitable for PCR, RT-PCR, and sequencing [45].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Nucleic Acid Isolation via CTAB Protocol

| Reagent | Function | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) | Lysis buffer; complexes with polysaccharides to remove them during purification. | Use a concentration of 2% (w/v) in the extraction buffer [45]. |

| PVP (Polyvinylpyrrolidone) | Binds polyphenols, preventing co-purification and inhibition of downstream enzymes. | Use a concentration of 2% (w/v); molecular weight PVP-10 is typical [45]. |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol (βME) | Reducing agent; helps to denature proteins and inhibit oxidation of polyphenols. | Add to CTAB buffer just before use (e.g., 200 µL per 100 mL) in a fume hood [45]. |

| Chloroform | Organic solvent for liquid-phase separation; denatures and removes proteins. | Use ice-cold; always handle in a fume hood [45]. |

| Isopropanol | Precipitates nucleic acids from the aqueous phase. | Use ice-cold for higher yield [45]. |

| Silica Gel | Desiccant for rapid drying and preservation of tissue samples prior to extraction. | Preserves nucleic acid integrity during storage and transport [45]. |

Detailed Protocol: